Kaori Tatebayashi is a Japanese ceramicist living and working in London. She comes from a family of ceramics traders, and was surrounded by traditional Japanese ceramics from an early age. After gaining an MA in Ceramics from Kyoto City University of Art, in 1995 she came to London on an exchange programme to study at the Royal College of Art. Kaori makes both sculpture and tableware, but it is her sculptural pieces, which are inspired by plants and nature, which I was interested to find out more about.

Kaori, you have a longstanding family relationship with ceramics. Can you tell me about this and how it influenced your development as a ceramicist ?

I was born in Arita in Japan, a little village renowned for Arita porcelain, which in Europe is known as Old Imari. My grandfather was an Arita-ware merchant and took orders from hotels and restaurants from all over Japan. The scene of my family gathering together to pack tableware commissioned from various potteries in the village in navy blue paper with our family company logo remain vividly in my memory as a fun event.

Each May, we participated in a pottery festival in Arita. My cousins and I were allowed to sell little porcelain figurines next to adults selling tableware and, when we sold the figurines, we were treated with too many ice creams by visiting relatives. In 2016 Arita celebrated 400 years of porcelain production. Although I don’t work in porcelain, ceramic is definitely in my blood.

You studied ceramics both in Japan and then in London. Can you tell me about the key things that you learnt in each place ?

In Japan, we were taught as if you were apprenticed to a master potter, learning everything from traditional spiral wedging, which they say will take 3 years to master, to throwing and hand-building techniques to firing electric, oil, gas and wood fired kilns. By the time you graduate from university, you have learnt everything you need to know to run your own ceramic workshop. It was about skill-based making at BA level then, for the MA, you focussed on how to express yourself in clay and with the range of ceramic material.

During my exchange at the Royal College of Art and a short residency in Denmark, I was liberated from all of the rules and restrictions and the traditional approaches towards clay and glazes I had blindly been studying in Japan and my work changed dramatically, especially the finish.

In order to make what I do now, I needed all the skills I gained from the training I had in my university years in Japan as well as the freeing of my mind which I got from studying in the U.K.

Why did you decide to stay in London to continue your ceramic practice after finishing your studies ? What did the city offer you that Kyoto didn’t ?

After my exchange at the RCA, I went back to Kyoto to finish my MA then lived in Tokyo for over 4 years mainly teaching, but I didn’t enjoy my life there. I missed being close to nature and couldn’t find my place in Tokyo which was too fast, too vast, and I felt the life there had no sense of the seasons. I moved back to the U.K. in 2001 and have stayed here ever since. People are surprised when I say London is full of green and that life here is much calmer than in Tokyo, but it’s true. I don’t feel the urge to be near nature in London as I did in Tokyo.

Also I choose to live and work in the U.K. because my sculptural work was better received here than in Japan, which was still very much stuck in tradition then.

You started making ceramic sculptures of inanimate objects, especially clothing. What was your impetus for making these pieces ?

Individual objects were my early pieces. At that stage, I was curious about how far I could push the material and challenge my skill. Also, my focus was on memory. The clay’s ability to capture time and its elusive existence, simultaneously having both fragility and permanence, overlapped with my ideas about memory. I was making old-fashioned, everyday objects which encouraged people’s memories and played with the sense of time being stopped.

I started making sculpture in my university days, and it was the reason I came to study at the RCA. Ceramic sculpture didn’t have a place in the world of traditional Japanese ceramics. Making tableware came after graduating with my MA, when I was teaching full time. My short periods of free time only allowed me to make small, repetitive pieces and so was most suitable for making tableware, which also came naturally to me due to my family background.

Can you explain the development of your work from the replicas of single items of clothing to the more formal tableau installations of multiple pieces which included a wide range of different subjects ?

My focus was on the challenge of replicating each item. In a way, I was training myself, developing my skills further. You could see them as my studies. Once I had mastered the required skills, I started to create still life series, much as you would do with drawings.

Where did your most recent and current interest in plants, flowers, fruits and vegetables (and insects and animals) originate and what is the link between these pieces and your earlier work ?

My passion for gardening started influencing my work gradually, but even in a much earlier stage of my life, my grandfather who collected and named some wild orchids from his local mountain, must have seeded something in me as well. My very first flower piece appeared in 2005, which I made for Ceramic Art London held at the RCA (it has now moved to Central St. Martin’s). It was a single rose stem, forgotten and dying in a vase. A moment preserved in ceramic, which later became my main theme. In the true sense, I am not trying to preserve plants, but time itself. By preserving plants, which have a very short life, you get the sense of time being captured and permanently frozen. I often add insects and other creatures, especially snails which, although they have movement, it is very slow, in order to enhance this sense of time being stopped.

Can you tell me about your working process ? How do you make your flower pieces ?

I usually work by going straight into modelling in stoneware clay, observing real flowers and plants from 360 degrees. I quickly calculate what method is most suitable to use, which part I should make first, the drying time and which is the best forming technique to use. I have been working in clay for nearly 30 years now. By looking at object, I can immediately tell if the object is at all possible to make and how to achieve the form.

The tools I use are very simple, my hands and a knife which I made myself. If it is a flower, I make it petal by petal, no secret or magic involved!

The pieces must be dried slowly, then fired straight to 1250°C without a bisque firing.

Can you tell me about the Banquet pieces and the work that you created for your exhibition at Forde Abbey ?

The Banquet is one of my largest installations. It was developed from my small still life series and I wanted to create a large flamboyant scenery based on the feel of the Dutch Old Master painting.

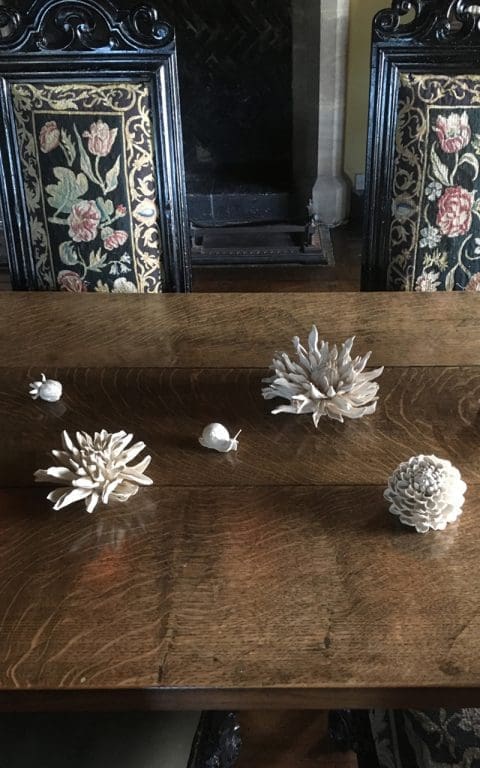

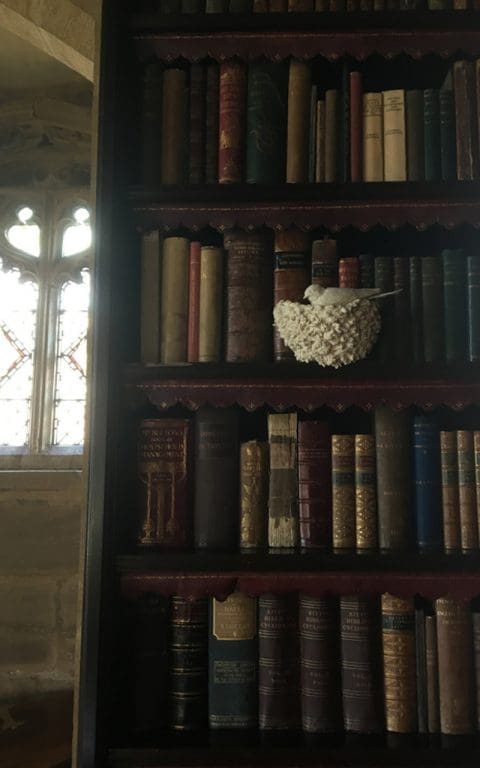

The work exhibited at Forde Abbey was my first site specific installation, which I created in my studio after a week’s residency there. To correspond to the feeling of the 900 year old library and the beautiful gardens and nature there, and because the exhibition was held in September, I created dahlias which I scattered down the central table, pumpkins (the originals of which had been grown in their kitchen garden) peeping from between the old books and swallows nesting in front of the book shelves. I wanted a fairy tale aspect and a slight spookiness, but not too conceptual so that visitors could really enjoy the experience.

What was the inspiration for the black stoneware pieces, Lunar Eclipse and Night Garden, Delft and the pale stoneware Paradiso di Flora?

Again, I was inspired by Dutch Master paintings.

At Ceramic Art London, I designed my stand to show the pieces, one side in black and the other side in white clay, the mirror image of the same object in black and white.

Black clay has a totally different feel to the white. Mysterious, dark and somewhat more intriguing. I want to experiment more with black clay in the future.

What are you working on the moment and are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with and why ?

I am working on the pieces for my solo show in Tokyo happening at the same time as the Olympics next year. And from Spring onwards, I will be working on botanical pieces for my solo show at Tristan Hoare Gallery in London in November 2020.

I have been studying the school of Japanese old masters known as Rimpa which started developing from 15th century onwards, reaching a peak in the 17th century. Japanese paintings in general are very seasonal and plants and flowers are often the most significant subject of their paintings. I am interested in creating a British version of them with wild flowers and plants native to this country or popular cultivars from that particular era, perhaps.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Studio photographs: Huw Morgan | All other photographs: Kaori Tatebayashi

Published 14 December 2019

Previous

Previous

Next

Next