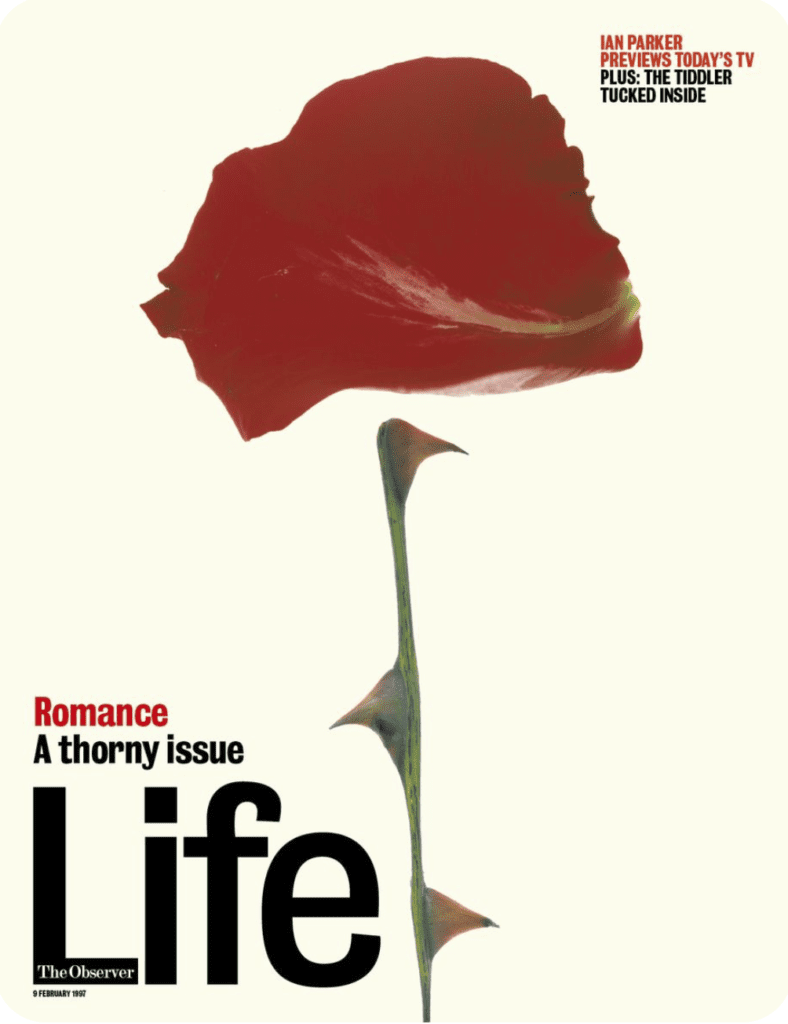

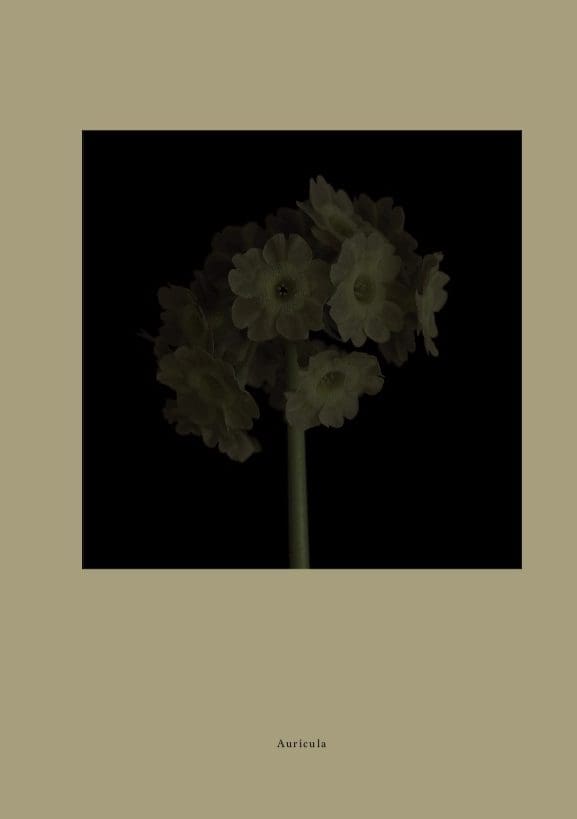

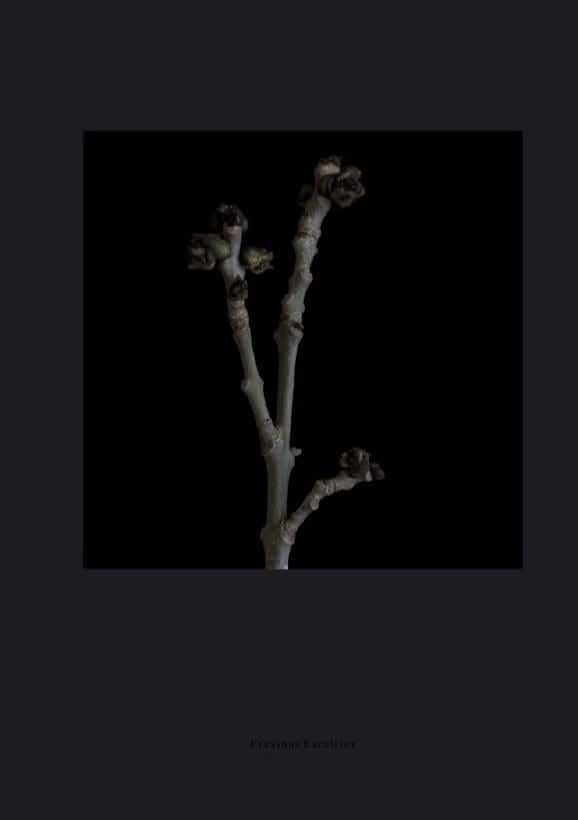

Fleur Olby first came to our attention in the 1990’s with her striking abstract plant portraits which illustrated Monty Don’s gardening column in The Observer Life Magazine. Her interest in shooting in low light prompted us to invite her to photograph the winter garden. So, early this year, and just weeks before lockdown, Fleur came to spend a day and a night at Hillside. As the clocks go back we revisit her vision of the penumbral garden.

Tell me about your interest in nature. When did it begin and were there any key experiences that shaped your relationship to the natural world and plants in particular?

During childhood I became ill with double pneumonia and had to be in an oxygen tent. My Mum brought an oak leaf into the hospital as a gift to look at something beautiful and magical from a tree close to where we lived and the thought of visiting it when I was better. I remember visiting the tree later, although now it all feels dreamlike. There was something then that I still question in the shift in perception of looking at something small in isolation to seeing it in its context of growing on a tree. The enlarged gaze of a child was full of wonder, magic and intrigue, something I have tried to recreate in my still life photography.

How did you realise you wanted to become a photographer?

During my MA in Graphic Design at Central St Martins (1992), I spent a lot of time colour printing in the darkroom, my degree show became purely photographic – Images of environmental and flower still life. My thesis explored the different ways of looking at Nature from abstraction, the single image, still life, the object in its environment, the concept of the Wilderness and a Garden and their uses within the industries of Art, Design and Photography.

I wanted to be able to work within the landscape I grew up in and the magazine aesthetics of still life. At this time, I was entranced by looking at detail, but importantly when I first started making pictures in wilderness places there is an unexplainable feeling found through the camera.

Your work for The Observer Magazine was groundbreaking at the time. Can you explain how your view of plants differed from the norm then?

I was inspired by Monty Don’s writing and both degrees were fine art graphic design – lighting and composition were always experimental. Nick Hall was my first commissioning editor at the Observer and then Jennie Ricketts. He commissioned the garden articles to be an abstraction in still life. The concept of the garden as a still life representation was different then. It was a unique time when my imagery was young and given total creative freedom. For the articles, I would regularly be at the flower market at 4 am and in the lab processing the work at midnight ready for the morning.

Although you were working commercially what made your photography stand out then was that it was clearly the vision of an artist. Can you describe you and your photography’s relationship with the worlds of art and commerce and do you still produce commercial work?

I had a good mix of editorial design and advertising and the two books were the fine art application of my work. After the 2008 financial crash and the evolution of digital capture still-life Photography commissions changed and lifestyle photography replaced a lot of the still life work. After 15 years of commissioned work, I had to change my practice as it became unviable to run a still life studio. I consolidated my archives and started to make personal work. The series are ongoing, but I would also like to work on plant collections again and garden stories.

How did your work develop after your time at The Observer ? I have read that some of the images were used in installations. Now you produce limited edition imprints alongside prints.

The Observer gardening editorial was amongst editorials I contributed to regularly for food and health and beauty. When I stopped shooting for the gardening articles in 2002 the food still life increased and I also worked for some fashion companies for still life and jewellery, perfume and interior still life.

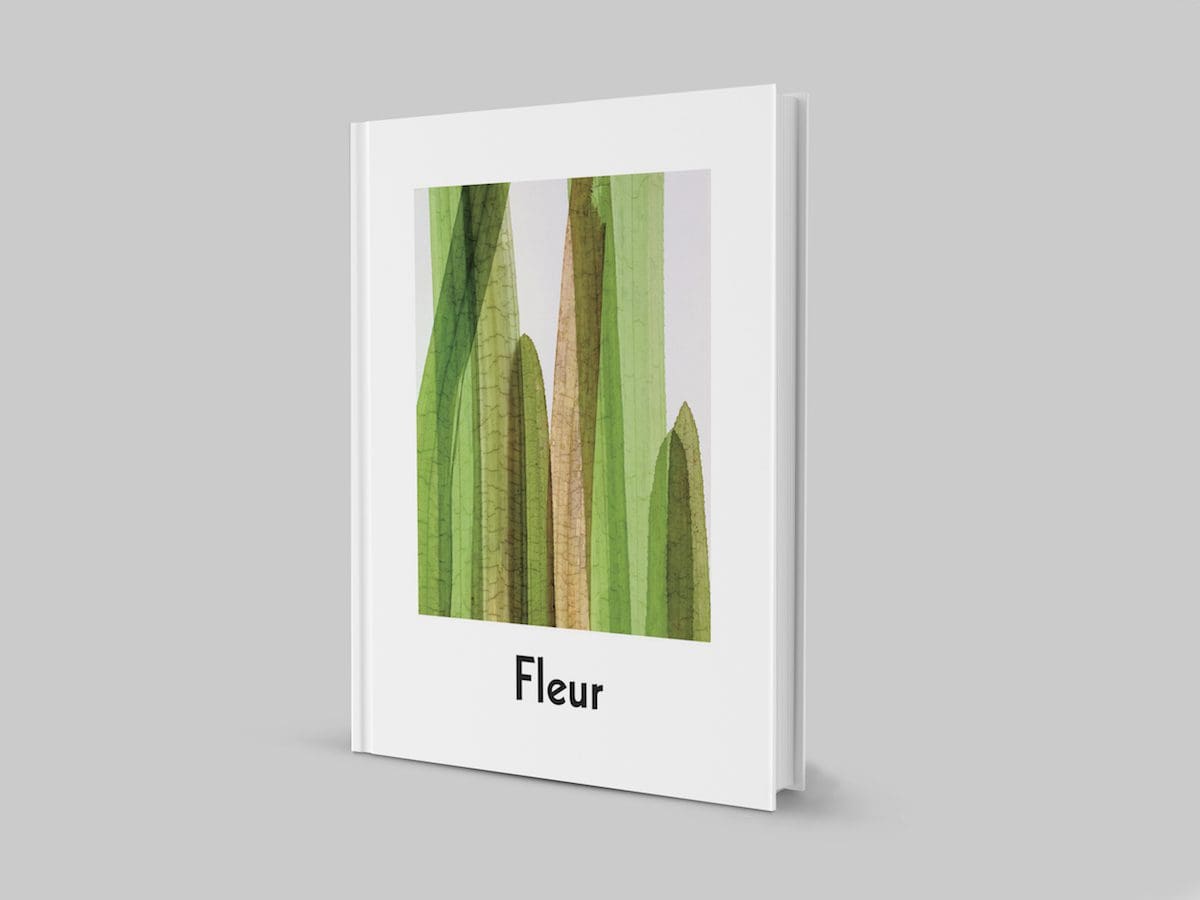

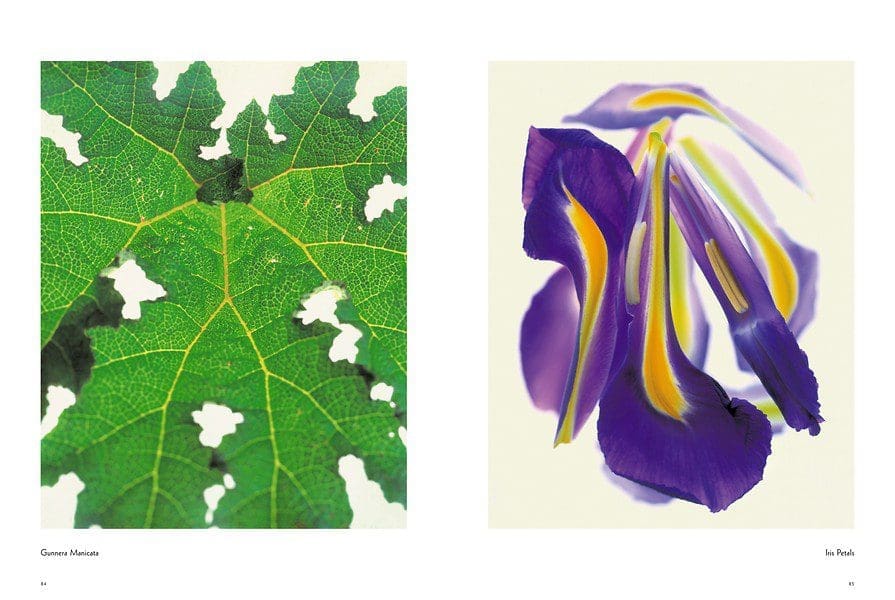

My monograph Fleur: Plant Portraits by Fleur Olby with a foreword by Wayne Ford, was published by FUEL Publishing in 2005, a combination of commissioned and personal work from ten years of floral still life. It was in the Tate Modern and The Photographers’ Gallery bookshops and distributed internationally with DAP and Thames and Hudson.

But after 2008 with two client insolvencies causing further problems after the financial crash, it took me a long time to find a way forward with my archives. The two commissions, Horsetail Equisetum for Gollifer Langston Architects and a textile collaboration with Woven Image in Australia were the archival commissions from that time that enabled me to move forward.

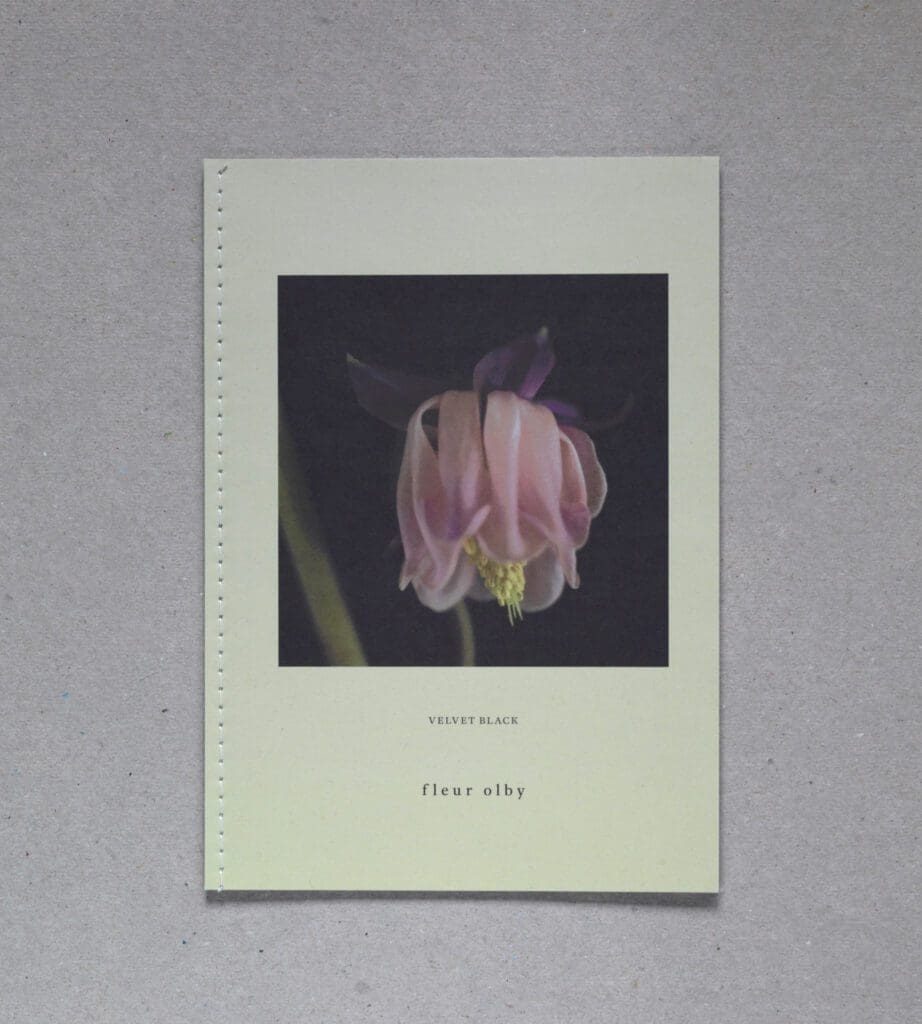

I had started a long-term project about the connection with Nature, Colour from Black. My Imprint has the first publication from these series, Velvet Black and limited edition prints that have exhibited at the Photography Gallery in the Museum of Gdansk and my solo show earlier this year at The Garden Museum, London. The A5 publication launched at Impressions Gallery Photobook Fair in Bradford and the A5 and A6 special edition are currently also at The Photographers’ Gallery bookshop in London. I aim to continue with self-publishing the series in small books and work in collaboration on the projects that evolve from them. Images from other series have also been shown in group shows in the UK and abroad.

Can you describe your process, and how your choice of film stocks, different formats and use of low light levels create the particular viewpoint you are interested in capturing?

The series artistic aim is to connect dreams and reality and through this work I have experimented with different mediums. It is less about the impact of a single image, my interest is in the pace and change of the narrative. The personal aim is to conserve plants and the elemental feeling of beauty in Nature. My commercial work was studio light, mostly shot on 5/4 Velvia and Provia film.

In my long-term series, the colour is subtle but fully saturated, in natural light. The low light started with the series Velvet Black as a present-day ode back to Victorian plant theatricals, collections and plants from a garden – the correlation between the transience of daylight and blooms.

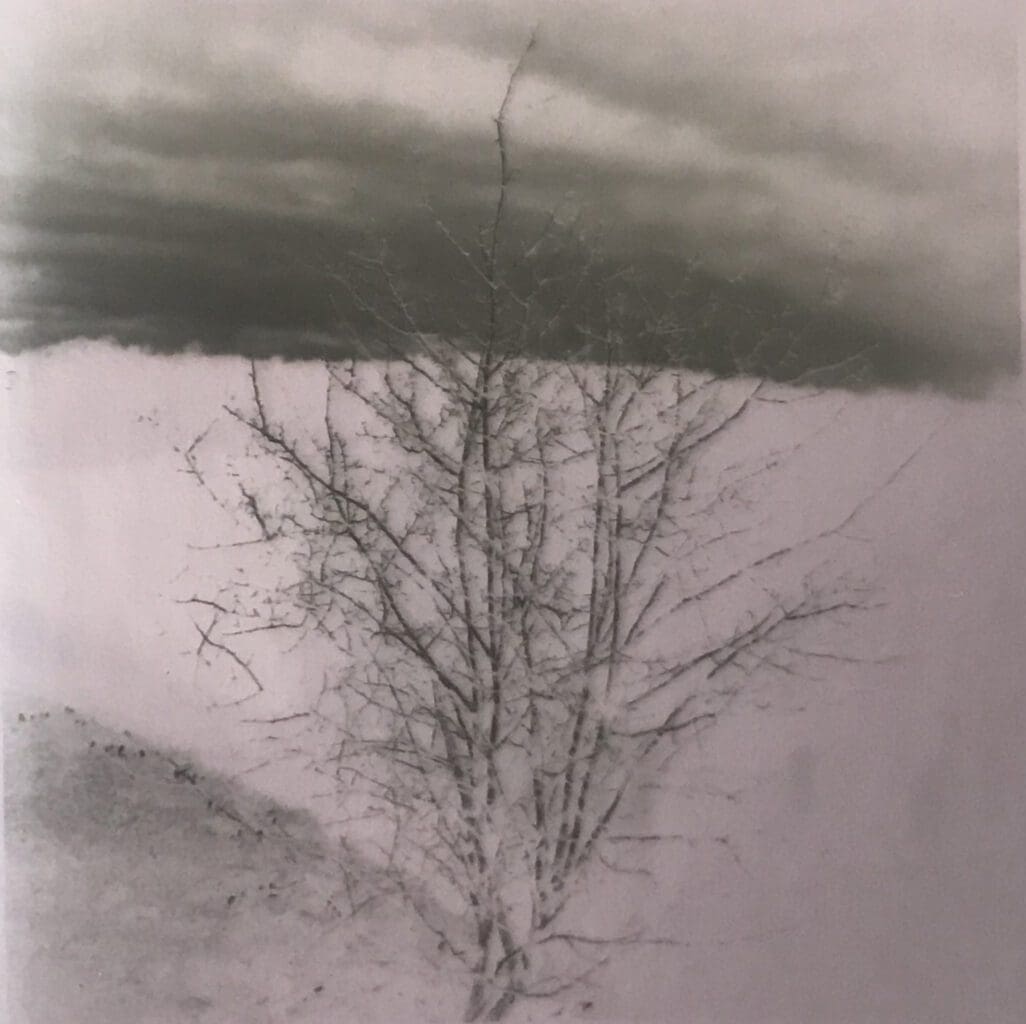

I was also experimenting with my iPhone as I was trying to capture the spontaneity of feeling from walking. My working process has evolved: It begins with walking and pictures that I revisit on medium format for a different kind of precision that allows long exposure. I am now mixing instant images and film from Black and white and colour. The series made at Hillside was the first time I combined the different mediums and shot Dusk, Dawn, Dusk in succession. I used Instax and my phone to find viewpoints from the paths. I remade some of the images on the Ipad to map out the plan.

Then I shot with a Polaroid camera in reasonable light and shot film and digital on medium format at Dusk and Dawn. The film was mostly Ilford, HP5, FP4 and XP2.

There is a quiet intensity to all of your work, a feeling of being tuned in to a different way of seeing the familiar. The fact that you work in series also gives a very strong narrative quality to your images. What would you like us to see in them?

Thank you, that means a lot to me! The quiet intensity was what I needed to reconnect with when I began to revisit childhood places that inspire me on the moors, on the hills, in the garden.

With the narratives about Nature, I wanted to slow down the viewing process and to question the feeling of Beauty through light and repetition within the series. In the book Velvet Black I use the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper and the folded pages to slow down the process in a similar way to a flower press. And the printed absorptance of the page makes the transient process of nature into a permanent object.

There is a distinct balance in your work between wild, elemental landscape and the intimacy and perfection of a single cut flower. What is the relationship between these two worlds for you?

I think this is the path I am trying to narrate between the perfect oak leaf from my childhood to the tree out on the hills.

When we asked you to come and take photographs at Hillside what were your first thoughts ? When you were here were there any particular observations you made about photographing a garden set in landscape?

It was great to hear from you both. I was excited about the thought of visiting Hillside. I remember our conversations about the work you were inviting artists to make and what aspects of the garden they were focusing on. But on arriving I couldn’t think how to divide it up into one particular interest and I knew I wanted to convey feeling.

I arrived between the storms of February, the quiet calm lull in the garden was breathtakingly beautiful. No-one was there until later today.

I started to walk – the paths led me everywhere. Enclosed and defined by the garden in and out of the landscape. I did not know this terrain, the feeling and scale are different, the quiet remains the same – the shape of the hill on the left is gentle and round, it stretches out into another at the front with incredible mature trees. The main garden is perched high up within the undulation of the hills. How will I capture this?

I felt I was intruding the serenity of the place, I stood amongst the plants’ skeletons taller than me and thanked them for remaining standing despite the storm – looked out at the echo of the trees beyond, walked down the hill towards them and looked back up to where I’d been standing – It is like a painting, brushstrokes of layered texture highlighted by the time of the year and the trees and hedges beyond it, darker shapes in repetition above. Light in colour as its ready to be cut for new planting and the two gates take me in and out of place and garden and into wonderment. I’m not sure I can express this.

Then there’s the bridge at the bottom of the stream with wrapped up plants on the edge that I could spend all day shooting, the vegetable garden! The artichokes! The Cavolo Nero – The two architectural stone troughs define the scale of the outdoor space and feel spiritual, a verbascum ode nearby reminds me of my Dad and makes me smile, the hedges, the orchards and the young woodland at the back. Flowers resiliently here and there touched me – intricate planting inspired me. I had to process a plan and start.

I wanted to try and capture this movement, the feelings from walking this dreamworld and its reality. I worked on different cameras in repetition in positive and negative to intensify the shapes and colour and black and white to intensify the feeling and pictorially play with resonance.

Do you feel that you learnt anything new from the time you spent photographing here?

It was immensely helpful to be invited to work like this, and I enjoyed the intensity of making the work. I made a new working process shooting 3 formats and running between captures to put the instant film to process inside and continue with the film outside. I made quite a lot of work in the time and it was the first time I shot constantly connecting dusk and dawn.

It enabled me to see how my work has progressed more clearly and how I can put it together because it was the perfect balance of how the garden and landscape coexist.

How was lockdown for you creatively?

Lockdown happened during my show at The Garden Museum.

I contributed to Quarantine Herbarium’s cyanotype project and the Trace Charity Print Sale which raised money for the charities Crisis and Refuge.

I listened more to the birds, watched the animals’ paths and felt exceptionally close to them and that continues. I was also busy shielding family, and I spent more time growing vegetables which I do as much as possible.

I stopped shooting and started to edit more.

What are you working on now and can you share any ideas you have for future projects?

I have had to revise my plans for this year, events I had committed to were cancelled. I am reworking everything and plan to bring the next series out in 2021.

The full edit of the photographs Fleur took can be seen on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Portrait: Howard Sooley

All other photographs: Fleur Olby

Published 24 October 2020

Previous

Previous

Next

Next