As September light casts its autumnal influence, the hips have lit up the hedges. Though it would be easier to get on the land to cut the hedges whilst it is still dry, we choose to wait until February in order to preserve their bounty. The birds work the heavy trusses of elder first, then move onto the wild privet before starting on the rosehips. Their fruits are still taut and shiny and it will be a while yet before they start to wrinkle and soften to something more palatable. If you are quick enough to get there before the birds, this is the perfect time to harvest them, the hips coming away easily to sticky your hands and stain fingertips scarlet.

Although I planted a couple of dozen eglantine whips (Rosa rubiginosa) to gap up the hedges when we arrived, I raised a batch of seedlings from the first hips they bore. An autumn sowing spawned more seedlings than I could deal with after the winter chill they need to break dormancy. I potted up a hundred seedlings and grew them on for a summer so that, a year after sowing, they were ready for planting out. Two years in pots (with potting on) would have made them stronger and probably more resilient to the fierce competition of being out in the wild, but the seedlings that did make it through are now doing handsomely.

Rosa rubiginosa

Rosa rubiginosa

The eglantine seedlings were planted widely, so that their perfumed foliage accompanies us on the walks we make over the land. They appear close to the gates and the stiles in the hedges, so that their apple-y perfume catches you unexpectedly and where they break free into the meadows. Six years after sowing, the best plants are now as tall as I am and weighted with fruit. Where we have deer down in the hollow above the brook, they have been left completely alone where other plants have been grazed, so I have also started to use them around the garden and as perfumed hedges in the hope that their scented foliage acts as a deterrent. Deer love roses as a rule, but dislike perfumed foliage, so the eglantines may be prove to be as useful as they are beautiful.

Rosa spinossisima

Rosa spinossisima

We have several forms of Rosa spinosissima now throughout the garden, but my favourite are the plants I raised from those I found in the sand dunes of Oxwich Bay on the Gower Peninsula. Growing to not much more than a foot, which is small for a Scots briar, the plants were growing sparsely and in pure sand amongst bloody cranesbill and sea holly. Their flowers had long gone, as it was late summer, but the round fruits were black and shiny. I gathered a couple and the resulting seedlings were set out two years ago now in an exposed position on our rubbly drive. Though the plants are heartier, growing to twenty four inches to date in our easier growing conditions, I am pleased to see they have retained their diminutive presence. We will see over time if they form thickets to the exclusion of the violets and crocus I’ve paired them with, as the briar is prone to move and colonise ground by runners. The creamy cupped flowers run up the vertical stems in early May, but the inky hips have been good since mid-summer and are only just this week starting to wrinkle and lose their gloss.

Rosa glauca

Rosa glauca

Though young and not yet expressing their stature in the garden, the Rosa glauca (main image) are sporting their first hips this year. The single flowers, which are small but always delightful, come on the previous year’s wood, so I will be making sure to always have some old wood for fruit. This is a foliage rose first and foremost and some books recommend coppicing every two to three years to encourage the best smoky-grey leaves, which are a perfect foil to the hips. I prefer to prune a third of the eldest limbs to the base at the end of winter to retain wood that will flower and fruit the following year. Ripening early for rosehips, they are bright and luminous, aging from scarlet to mahogany, and are some of the first to be stripped by the birds.

Rosa moyesii

Rosa moyesii

The young Rosa moyesii on the banks behind the house are also showing good hips for the first time this year. These scarlet dog-roses are good amongst the cow parsley and meadow grasses that spill from the hedgerows in June, but their flagon-shaped hips are arguably their best asset, making this rose easily identifiable when fruiting. With arching growth and fine apple-green foliage, I will let the shrubs run to full height, which may well be ten foot or so if they decide that they like the position I have given them. They have room here on the banks and this is the best way to appreciate them, from every angle and with the yellowing autumn sun in their limbs.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 15 September 2018

This time last week we were still reeling from the excitement and stimulation of the first Beth Chatto Symposium. Originally intended to celebrate Beth’s 95th birthday this year, following her death in May the event became both a memorial to her and a celebration of her influence on a generation of gardeners, designers and nurseries, both here and overseas.

The symposium was the idea of Amy Sanderson, a Canadian gardener and florist who has spent some time working at the Beth Chatto Gardens in recent years, and was organised by Amy, Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg. When the symposium was announced early this year they anticipated in the region of 150 attendees, and so were thrilled when over 500 people from 26 countries bought tickets. Åsa told me that they could have sold many more.

The theme of the symposium was Ecological Planting in the 21st Century, and the line-up of international speakers included gardeners, garden designers, academics, nursery-people and growers, all with their own take on the subject, although a number of key themes became apparent over the two days. The talks were recorded and will be posted on the symposium website as soon as they have been edited.

In the main image above are, from left to right, James Hitchmough, Dave Ward, Taylor Johnston, Olivier Filippi, Marina Christopher, Peter Janke, Dan Pearson, Midori Shintani, Keith Wiley, Andi Pettis, Peter Korn, Åsa Gregers-Warg, Cassian Schmidt and Amy Sanderson.

James Hitchmough

James Hitchmough

Opening and closing the symposium were presentations by James Hitchmough, Professor of Horticultural Ecology in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Sheffield. James has done a huge amount of research into seeded naturalistic plantings over the past 30 years and, as an academic and researcher, was generous and instructive in the information he shared. He was very clear in communicating the ecological value and function of designed landscapes, but explained that the highest value and most stable functioning of a planting is achieved through its ability to persist – its longevity. This is directly linked to biomass, since the denser a planting is both above and below ground, the less unwelcome weed species are able to invade it. The layering of foliage above ground, from groundcovers through to tall emergents, also shades out weed species, creating a more stable planting. He advised that the biggest challenge in dynamic naturalistic plantings is identifying what they are to become and how to manage them with this guiding vision in mind. All of these observations rang true.

Keith Wiley

Keith Wiley

All of the speakers spoke about the inspiration they have taken from observing native plants in the wild, and both Keith Wiley and Peter Korn spoke passionately about their travels to Crete and South Africa, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and North America, respectively as being hugely influential on the ambitious private gardens they have both created in Devon and Sweden. Keith was, for 25 years, the gardener at The Garden House at Buckland Monachorum, one of the most influential gardens of the 1990’s in bringing naturalistic planting to the attention of a wider audience. His talk focussed on the aesthetic possibilities of combining plants as they appear in nature, and he illustrated it with lush images of highly colourful, exuberant plantings.

Peter Korn

Peter Korn

Peter explained the challenges he had set himself by wanting to grow as wide a range of dry-climate plants as possible from all over the world, in an inhospitable climate and with the added difficulty of high rainfall and sub-zero winter temperatures. Both explained in detail the lengths they had gone to in order to create specific microclimates and soil conditions to allow them to grow some of their favourite species. Of great interest was Peter’s method of growing plants in deep sand, which both encourages the formation of stronger mychorrhizal communities and presents a hostile environment for self-seeding weeds.

Cassian Schmidt

Cassian Schmidt

Similarly, Professor Cassian Schmidt, Director of Hermannshof Garden described the creation of a large number of habitat types to showcase a wide range of plants in this public garden located in Weinheim, near Heidelberg. Originally based on the ecological principles of Professor Richard Hansen, Hermannshof now has in excess of 18 habitat areas from North American Prairie to East Asian Woodland Margin and European Dry Steppe. In tune with James Hitchmough, Cassian also described the importance of plant ‘sociability’ when planning plantings, choosing plants with compatible growth habits and cultural requirements to build persistent, self-regulating communities. His experiments with dense plant layering, and the use of primroses as an early-season, weed-supressing groundcover encouraged us in our own thoughts about these as a means of closing the ecological gap in our own plantings.

Peter Janke

Peter Janke

Fellow German, nurseryman and garden designer, Peter Janke, worked at the Beth Chatto Gardens as a young man in his 20’s, and was hugely inspired by Beth’s experiments and success in the Gravel Garden. After returning home he introduced her teaching of using plants best suited to the habitat conditions in one’s garden to an audience of German gardeners. Peter spoke about the challenges posed by the recent high summer temperatures, which have been especially extreme where he lives in central Germany, and described how he created his own garden, based on many of Beth’s planting principles, in particular a gravel garden of his own, which has performed remarkably well this year.

Olivier Filippi

Olivier Filippi

French nurseryman, Olivier Filippi, spoke passionately about planting palettes for Mediterranean and dry landscape plantings, the development of which he is at the forefront of, supplying projects all over the mediterranean. Although many of the speakers talked of striking a balance between aesthetics and function, Olivier was very clear that, in a dry climate, a functional landscape is, by necessity, a beautiful one. He described the use of cushion-forming, evergreen sub-shrubs as key in his work, and flower as the least important aspect in making plant choices, leading to an appreciation of the ‘black and white garden’ where rhythm, form, texture and contrast are the primary considerations. He also spoke vigorously about the need for water conservation and encouraged the audience to regard maintenance as one of the most enjoyable parts of gardening. He was also dismissive of current trends for using only native species in plantings, arguing that, in relation to the scales of planetary time and geographical change, such a stance was limiting and myopic.

Andi Pettis

Andi Pettis

As a complete contrast Andi Pettis, Director of Horticulture at The High Line, spoke of the very particular challenges of gardening in an extreme urban environment. As well as the technical and organisational difficulties of maintaining a podium garden high above the ground. She also focussed on the relationship between the public and plants, and the fact that people are also a part of landscapes and their associated ecosystems, whether natural or designed. Like Cassian Schmidt she also spoke passionately about the educational benefit of a public park where horticulture is paramount, and how, even in the centre of one of the busiest cities in the world, it is possible to get people to engage with and appreciate natural cycles and rhythms and ecology.

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan had also been invited to speak, and he did so primarily about his work at the Tokachi Millennium Forest, although he too illustrated the fundamental impact that Beth Chatto had had on his early understanding of plant habitat requirements, and the importance of creating planting schemes that are culturally balanced and in context with their surroundings.

His talk was followed by one given by the Head Gardener at the Millennium Forest, Midori Shintani, and her first public presentation in English. Midori talked of the ancient Japanese belief in animism, the power of all natural things, of the landscape, and of nature worship. She also explained the importance of satoyama, the term used to describe the territory formed by the intimate relationship between man and the productive agricultural landscape at the boundary of the wild. These ideas were then developed as she explained how she and her team of gardeners approach the work of maintaining, not just the designed landscapes at this public park in Hokkaido, but the very forest itself. She spoke beautifully and with great tenderness about the fact that everything is connected, and the importance of taking great care and making close observation of natural processes. She expressed the deep interconnections between people, landscapes, natural habitats, plants and fauna with immense simplicity and lightly worn wisdom. It was no surprise to find that, as she delivered her final words and the hall filled with applause, many in the audience were crying.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 September 2018

Lucy Augé is a Bath-based artist who has an passionate interest in the variety of flower and plant forms which she paints with Japanese inks on a wide range of specialist and vintage papers. Her intention is to capture the ephemeral and fleeting moment. We met last year and, after introducing her to the Garden Museum, she showed some of her new tree shadow paintings there earlier this summer. Since June, Lucy has been coming to the garden at Hillside to capture a range of the plants here on paper.

How did you come to be an artist ?

I always wanted to be an artist, even from being a child. For my tenth birthday I didn’t want a party, but wanted to go to Tate Modern, as it had just opened. I think my mum thought, ‘Oh God. Choose another career path !’. I had always been creative at school, I was never really academic, so I got funnelled down a channel into being ‘artistic’. That then followed me through to college, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist, so I did graphics, and thought I’d go into magazine design, as I had a passion for French Vogue at the time as it was so well art directed.

Then I had a really bad brain injury from a fall, and that left me very, very ill, at home. I couldn’t go back to university. I couldn’t do much, as I was having four seizures a day, and thought, ‘OK, life’s over’, but then I started gardening with my father, and that’s where I started noticing – I was going at such a slow pace, because I was so ill, I’d have to be carried down to the garden – and I started noticing things more, because I didn’t have any distractions. I didn’t have a phone for two years. Not that I was cutting myself off, I just didn’t need it. So I just started looking at nature all the time, and then I just started painting it. Repetitively. Or I was watching gardening programmes on repeat, because I wanted to know more, all the time. So, that’s where, through the illness, I got the passion for gardening and my painting.

When I finally went back to university I just felt it was very redundant for me. I went back to the graphics course as I was already a year in and because I don’t really like to give up, but I knew the tutors didn’t really like my work. They were looking for a very graphic, computer-generated style of work, and I then generally only worked in felt tip, keeping it hand drawn, but still trying to fit in with the current look that was around at the time.

So what happened after university ?

I got picked up for projects while still at university and, when I graduated, I did packaging design and worked with Hallmark, but I quickly knew I wasn’t an illustrator, as I can’t draw just anything and my passion lay with nature and studying that, rather than drawing a family of badgers eating cake. No joke, that was an actual commission.

The 500 Flowers exhibition came about after a month I spent in LA in 2015, where I had a meeting with the art director at Apple of the time, who had offered to mentor me. He set up a meeting with a carpet designer who I was supposed to do collaboration with. However, when he met me he told me that I wouldn’t be an artist unless I married someone rich, and that he would only work with me if I got someone to buy one of his rugs.

I was enraged by this and thought I was tired of waiting for someone else to launch my career for me. So I came home determined to make an impression alone, booked a rental gallery space in Bath and put on my first show on my own. The idea originally was to paint a thousand flowers, but that was near impossible in the time frame I had set myself. My brother calculated I would have to complete one every ten minutes ! So I painted five hundred, with the aim of painting every species that I came into contact with.

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

You produced all of that work and organised the exhibition yourself. What was that experience like ?

Well, I had five hundred A4, individually painted ink drawings, which I had completed in three months, and that both evolved my style and I became very confident at drawing. I also priced them at £40 each, which I think some people thought was madness, but at the same time nobody knows you, you have no reputation, and so £40 can seem like a lot for someone, but it was great because it made it affordable so that people would buy maybe nine or twelve at a time. An interior designer, Susie Atkinson, bought sixty. And so it got my name out there, because I was affordable.

The exhibition took place in Bath and I made sure I had beautiful letter-pressed invites. I invited everyone I’d ever met, contacts I’d made on Instagram or through business or who had shown an interest in my work. I invited people who I really admired for their work, which is why you and Dan got an invite. I just wanted to show people that this is what I do, this is my passion and if I fall flat on my face and no one comes and nothing sells, at least I would have known that I’d given it 100%. And then I’d have gone and got another job !

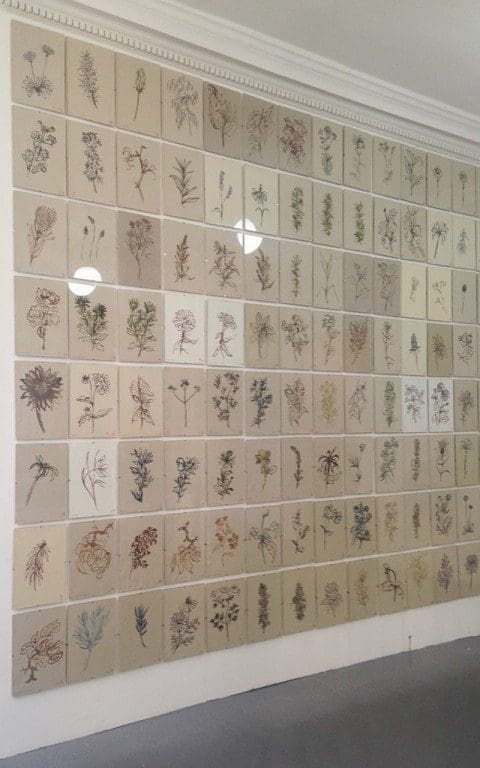

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

But it worked out in my favour. I had a queue out the door on the first night. I sold over eighty in the first couple of days. Then House & Garden emailed me to ask if they could have nine for their show, which the editor ended up buying. The assistant editor then bought another nine, and she put them up on her Instagram and I ended up selling out in five months. That then led to shows in Japan, San Francisco and elsewhere. It confirmed to me that, yes, you are on the right path, you’re doing the right thing, and the proceeds of that first exhibition went towards buying my studio. Before then I was working in a barn with no windows, no natural light, no loo, and so that exhibition was my make or break. Otherwise you can be creating, and calling yourself an artist and saying ‘This is what I do for a living.’ and yet you’ve never really put yourself out there, and so I thought, ‘baptism of fire’.

Then I started getting commissions from people to go and draw on their land, their flowers, which was really great. The best of those was for Gleneagles, which was the highlight of my career. I was flown up to Scotland, where I’d never been, and stayed at the Gleneagles, which was an amazing experience, and I went round the estate and drew all of the plants that were there at that time, and they are now hanging in the American Bar. And it was just so nice to know that people understood what you do.

Were you starting to charge a bit more for them now ?

Yes, I did raise my prices. Although I didn’t charge a lot because I wanted people to have the chance to invest in my work. I come from…my father grew up with no money, but he was always passionate about art, and just wanted someone from his background to be able to go, ‘I’m going to invest in something. Something beautiful.’ So that they can own real artwork. And I think that is a real gift to be able to do that. Especially as I had five hundred ! And the consequence now is that they have travelled all over the world. I love that there are some in Singapore, and some in Brazil and I don’t think I would have got that kind of international reach if I had not priced them so competitively. Of course, now my prices have gone up and I don’t need to produce as many. My last catalogue only had twelve paintings in.

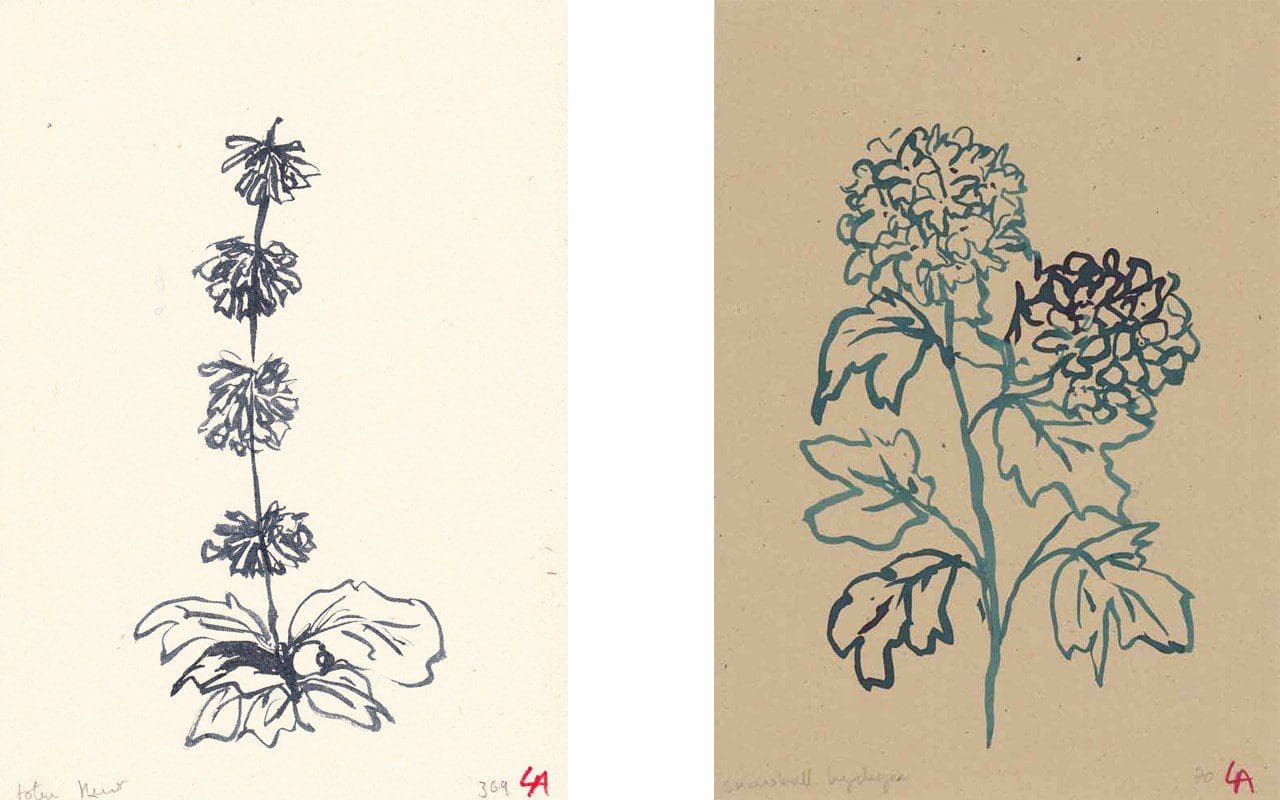

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

What was the medium you used for the 500 Flowers paintings ?

Ink. On antique paper.

I’ve seen some of your work which is very highly coloured and looks like it is done in felt tip ?

Yes, that’s right. That’s when I was still trying to be an illustrator. With those I was trying to fit in with the norm, so everything was very highly coloured for editorial. I would say that that was the only time I have ever tried to fit in. It worked for the clients to a point, but I kept being told, ‘Your work looks too much like you. There’s something to it, but it’s not commercial enough.’. So I gave it a year, doing that kind of work and I just grew out of it very quickly, because it wasn’t me.

There appears to be a strong Japanese influence in your work.

I love Japanese and Chinese art. I’ve always loved Japanese and Asian culture, so it’s always been in the background. Anything from there I could get my hands on I wanted to have a look at it, absorb it. Then I saw a show of Chinese paintings at the V & A, where I learnt that they were painting with natural pigments, so with copper and iron and earth and plants, and it just made this wonderful colour palette. So I found some Japanese inks that have that same antique colour palette, and it just felt much more me. It’s hard to put my finger on it, but it just started to fit better with the kind of images I wanted to make. And with the paper. I had never wanted to work on white. I had this antique paper, which had been in my godmother’s attic, which had the same feeling as the old Chinese papers I had seen, because they are made entirely from natural elements. So my choices were about aspiring to that antique colour palette. The other thing that struck me about that exhibition was that the artist was always invisible. The painting was never about the artist, it was about nature, landscape, weather, the seasons. It was about the everyday. And I thought, ‘Yes. Art can be like this.’ Because as I was growing up when everything was about high concept or shock, shock, shock or politics. The stranger the better. How far can you push it? And looking back at older art – one of my favourite artists is Monet – was deeply unfashionable and seen as suspect. But I love how he could just paint waterlilies and the resulting painting becomes this charged, emotional landscape.

Is that one of the reasons that you didn’t feel you could really be an artist ?

Yes, completely, and it’s one of the reasons I considered commercial art to begin with. Also I was never really encouraged at school, bar one teacher, to pursue my art. You were told that you needed to fit in. And I think as an artist you do need some kind of validation that what you are doing has value and that this is what you are supposed to be doing. And I never really got that until I put myself out there and had people say, ‘We want what you make.’ Because otherwise you can be drawing for just you – and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that – but you do have to decide that you are going to be an artist, and I made that decision after the success of that first exhibition.

I could have gone in one of two directions. I could have just put my flowers on anything and gone down the commercial route, or choose to refine the work and make it more considered. I have had a few commercial collaborations, but I have been very choosy about who I have agreed to work with or who I have approached. And I then reined it in and have now moved my work away from it, as people lost the meaning behind what I was trying to do. So they just wanted a picture of a lily as their daughter was called Lily, which is fine, but it missed the ethos of the work.

Which is ?

Seasonal observation through nature and plants. Forgotten moments. The immediacy of right now. I always found it interesting that the first pictures to sell out always are the ones of weeds. Those are the ones that people really want. I think because, as soon as you paint them, and strip everything away, you can see the beauty in them, and the fact that they are so mundane, but the painting elevates them. Honours them.

Do you know that there are 56 seasons in Japanese culture that relate to the flowering times of 56 different plants ?

No, I didn’t. How fascinating. I can so relate to that. I get quite anxious at the possibility of missing things. You know, like cow parsley. I’ll have a great idea, and then two weeks later I’ll have the time to get onto it, and all the cow parsley is gone ! So now I prep my paper in advance and cut it to the size that I want so that, when that moment presents itself, I can just say, ‘Here I come !’. That’s why when I came to your garden I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s definitely going to be, sorry to say for you, a much longer process than I had envisaged, as I now would really like to be there in different seasons.

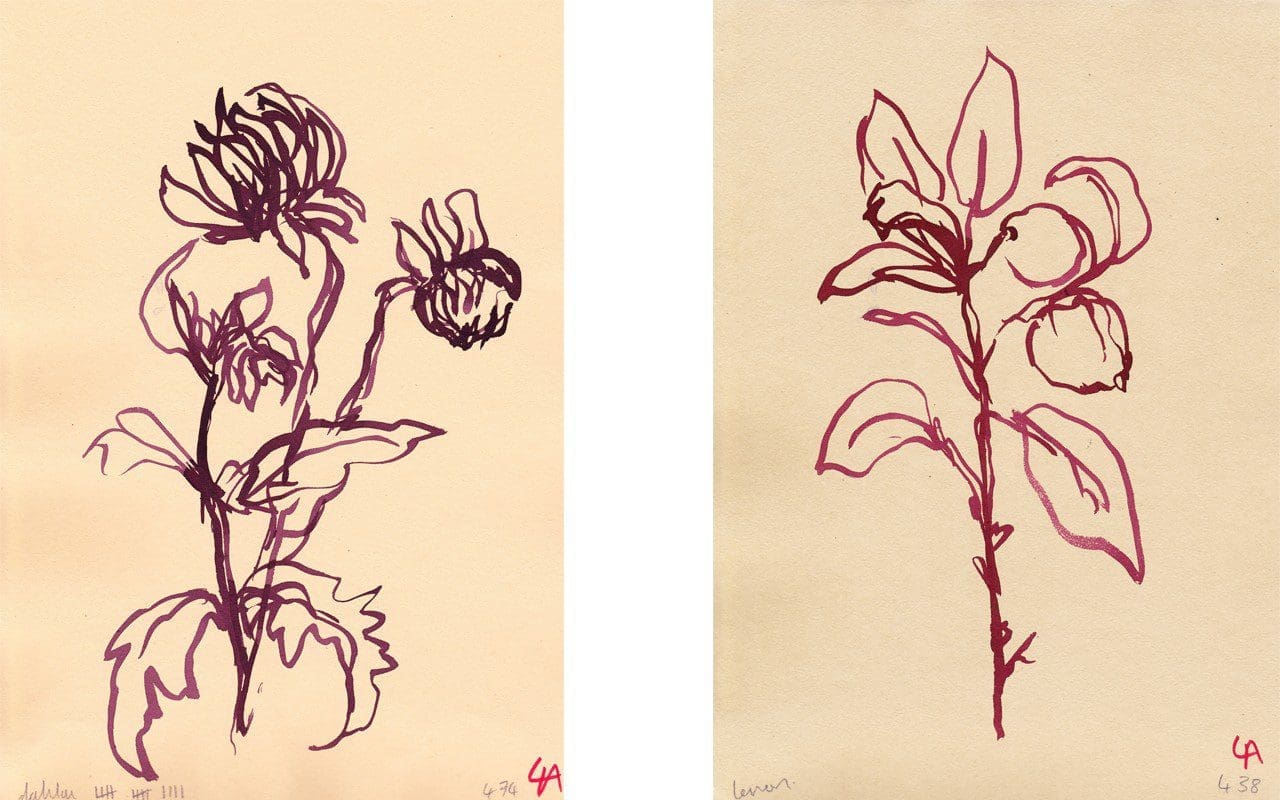

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

What does your work mean for you personally ?

Very generally it just gives me that quiet time. You don’t have to think about anything else. Once you get into a process – it’s a bit like gardening in a sense – it gives you that same mindfulness combined with productivity, which makes me feel at peace. You’re just drawing, or gardening, and that’s all you’re thinking about. And then sometimes you’re not even thinking at all, but are completely lost in the process of activity. That’s what I really love about what I do. It’s quite addictive. It empties your mind and is very meditative. I’m a worrier. I do worry too much and it’s quite nice to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to think about anything now.’ And I’ve always been quite confident in my own work, so it feels like a very safe space when I’m creating. And once I’m happy with it and happy to put it out in the world, it’s done and I can move on.

Until then – and that’s why I have my studio away, remote. I don’t want to hear everyone else’s opinions – I don’t actually show anyone my work until it’s at a certain stage, which is almost finished. It gives me a degree of freedom and escapism. Which is why it didn’t work for me as an illustrator, because someone else is dictating what you’re going to draw, your process is held ransom by deadlines, and I’ve never been any good at being told what to do. Ever. I will question and question to understand why I should do something. Just because I’m curious, but having it be just my own work I can ask my own questions and be curious about where it’s going to go next, how am I going to paint it. And I know what I am looking for, rather than what somebody else is looking for and wants me to produce. I do find it difficult when someone says, ‘I have a tree in my garden. Can you paint it ?’, because the tree might not be the thing in their garden that I would want to paint.

What are you looking for ?

In paintings I think it’s a stillness. I really want to portray stillness, or a captured moment. So everything has to be painted from life, because it feels fake otherwise. Sometimes I do draw from photos, but you’re just not capturing that moment when that leaf on that plant might have been at an awkward angle. You might not have seen that from a photo, so that’s really interesting to explore.

The 500 Flowers were all painted from life. Firstly, all near to me and around the studio, so a lot of wildflowers, but also some bought flowers, and that’s how I got in touch with Polly from Bayntun Flowers, because I looked up ‘local cut flowers’ online and saw what she was doing and I thought, ‘Brilliant !’. She had amazing heritage varieties and luckily, when I asked her if I could visit to paint, she said, ‘Yes. Come on round!’. I was like a child in a sweet shop. The first day was so exciting I must have made about forty paintings in one go. I would normally paint about five or ten. But the garden there was just chockablock with species, lots of which I hadn’t seen before, so it was very exciting and it got me up to five hundred !

But then it was hard when the winter came. I wasn’t aware of how much I would suffer. I became quite, ‘unusual’ in the winter, because I panicked and thought, ‘What am I going to draw ? Everything’s over. My work’s not good enough.’ It was really tricky. You’ve been doing all this painting and you’ve got this absolute high from painting all these things, because there are endless possibilities and inspiration in the summer, and then my first winter I didn’t know what to do. I was really looking and trying to paint winter, but really everything is just dormant and that’s when I realised I have to know what I’m going to do when winter comes. Not hibernate.

So now in the winter I paint a lot of dried leaves and stuff like that. The first winter I was so busy, doing commissions and collaborations, that I didn’t really notice. It wasn’t until winter 2016, a year after the show, that it was total panic. A flower desert. I thought maybe it was time to do some abstract stuff, get back into illustration. It was bleak. And then there was stuff going on in my personal life, and what’s going on in my personal life does feed into the work. If I’m having a grumpy day I will most likely pick out a mopy looking plant. It’s weird. I didn’t even realise it till someone else came to my studio and said, ‘This is all a bit melancholy.’ It’s frees such an subconscious part of your brain when you’re drawing, you’re not really thinking, you’re just observing. When I saw how my moods were feeding into my work I wanted to explore that more.

The paintings that I relate to the most, like Monet’s waterlily triptych, that he painted as a reaction to the war, is so powerful and emotive, and it is ‘just’ waterlilies, and I thought I would like to try and harness that emotional connection more and be more aware of it when I am working. So the tree shadows that I have been doing most recently came about because I had drawn so many flowers – I mean I was well over a thousand different flowers by now – and I was starting to fall out of love with them, even though there were commissions paying my bills. I thought, ‘I’m on the way to making myself into a performing monkey.’. I was getting set flower lists from people, with direction on paper and ink colours and I thought, ‘I didn’t start doing this to make ready-to-go flowers.’. It wasn’t me, and felt like I was heading back into illustration territory, which I had dragged myself out of.

But then it all changed because the farmer that owned the land that the barn I was renting died and so my studio tenancy went with him. I also had some financial worries. I didn’t want to paint another flower even though it was full on summer time and I was just lying in my studio taking a nap and I could see the reflections of the trees in the glass of one of my old pictures. And I thought it was interesting. I had also been experimenting with totally abstract ink paintings, which I would cut up and make into smaller single frames. But that didn’t fit in with anything that I was doing. But I started to think about how I could bring these things together. I started trying to draw the outline of the leaves onto the frame, but that didn’t look right. Then I started drawing outdoors, which I had always done. All five hundred flowers were drawn outside. But I couldn’t get a high enough outline definition.

That’s when I realised that everything moves so quickly. I would go and get my water bottle from the studio and, by the time I got back, the shadows had moved and the picture was different. That’s when I also started noticing the weather. Timing was everything. Before that I had just been aware of when each flower I was painting bloomed – this in when the roses are here, this is when the daisies look best – but not the bigger picture. When I was drawing the flowers I was more aware of the different varieties, because when you watch gardening programmes and learn that this is what a rose looks like, this is what an angelica looks like, and then when I would go out into the fields I would think, ‘Well, that has the same leaves as a rose. That looks like an angelica.’ And so then I was learning, without any books or anything, about those wild plants. Even though I didn’t know the name I was able to match them up.

What I was finding when I started doing the tree shadows was that , even when the shadows distort, they each have a particular look. Aa certain space between the leaves. The reason I like painting hazel is they have a lot of space between the leaves. I’ve tried painting quite a few different trees, but have found what works and what doesn’t work for me, for my aesthetic. I’ve also learned that, at four o’clock, you won’t be able to get hold of me, because the phone goes off, because that is the time I’ll be painting the shadows. That’s one of the things I noticed at your place. It wasn’t four o’clock. It was later. More like five thirty, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference, because that’s when you’ve got the high definition of the shadows, like on the irises that I tried doing. And where your site is so exposed the light seemed to move so quickly. I only had a half hour window, and that was it. Whereas where I am I can start at four and not finish until seven. The angle of the image changes, but at yours I was surprised at how the time made such a big impact. It’s taken months to understand that. When is the right time to draw. What is the best weather.

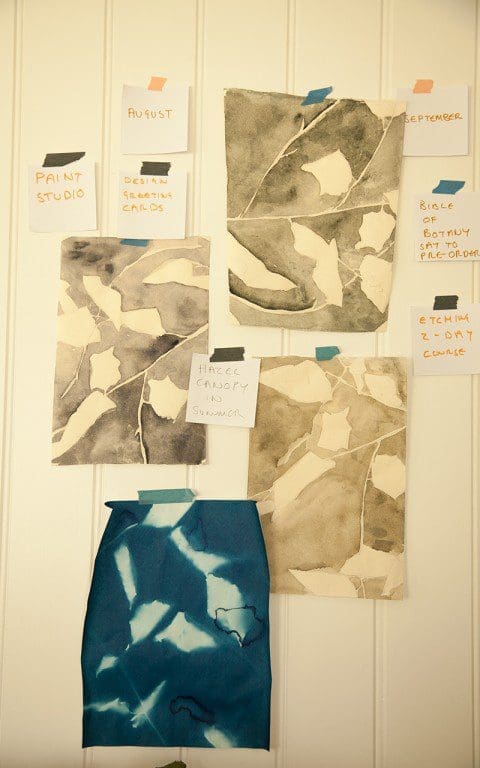

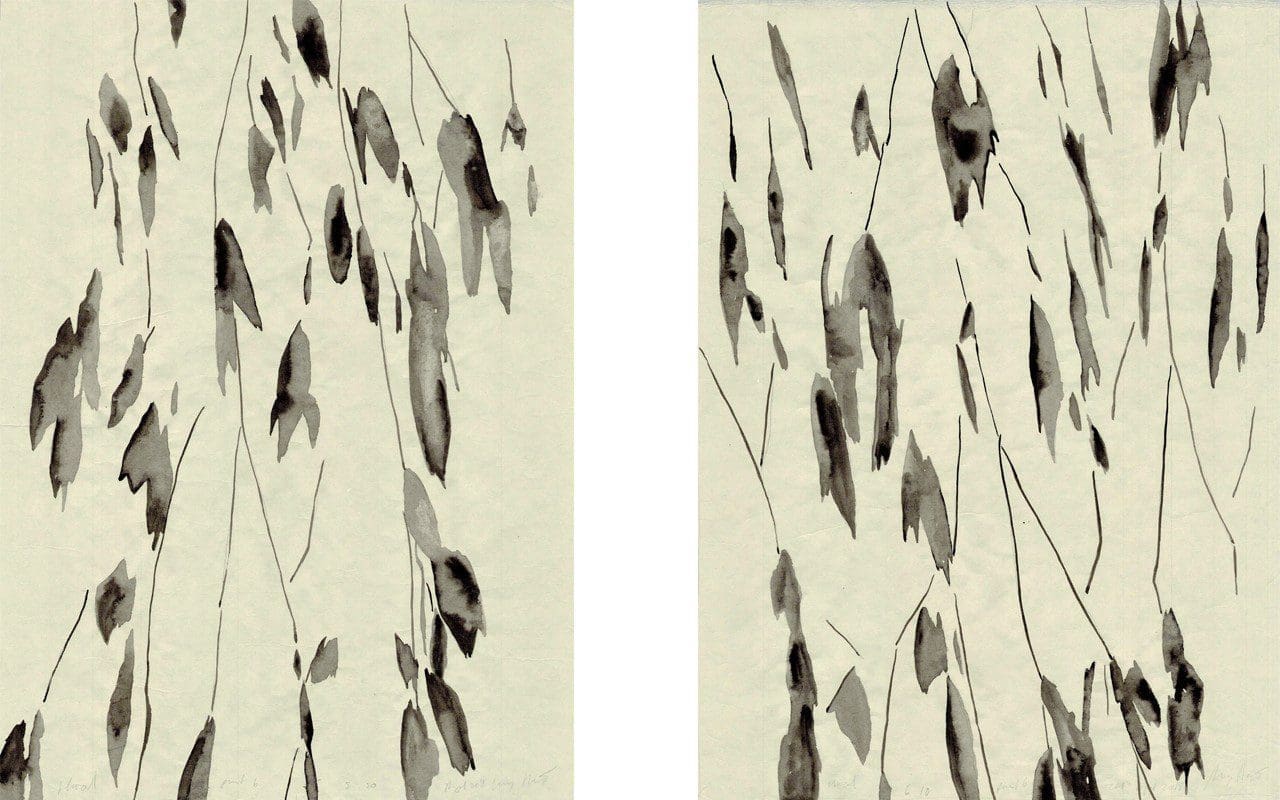

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

When did you start doing the tree shadows paintings ?

August last year. It was purely by accident. I had some leftover scroll paper and I had this birch branch and was trying to paint up into the canopy inside the studio. So I’d hung it up and then I saw that when the sun came in through the window, there it was on the ground. So I thought, ‘Oh, quick ! Get it down. Start drawing.’ I wouldn’t say that I’m drawing the outline, but more what I saw, because things move so quickly that you can’t get the exact outline, so there is a bit of interpretation involved, but I still want to be quite true to what it is, and if what it is turns out to be an awkward picture, I quite like that uncomfortableness.

So that first shadow painting, and I know this sounds cheesy, made me feel re-awoken again. I thought, ‘OK. Let’s restart.’ It was a risk, giving up on my flower paintings, which was bringing me in income, and then you think of going to your audience, who know you for your flowers, and saying, ‘I’m doing tree shadows now.’ But, the response was really, really positive. And it has been encouraging to hear people say, ‘You know I really liked your flower paintings, but I lovethe tree shadows.’

I think it’s because they feel more like art to people, whereas the flower paintings were more illustrative, the tree shadows are more abstract. But I think that doing the 500 Flowers gave me some validation, which means it is easier for people to feel comfortable with the change in direction.

When I was trying to capture a landscape through paintings of individual flowers – this is what grows here, this what I have seen and recorded – when I was in Scotland the flora there was very different, and it created en masse a very different painting. Different shapes and texture. Quite thistly, spiky plants, due to the hardier conditions up there. But not everyone got that, whereas everyone seems to get the tree shadows. I’m just really enjoying exploring it and see where it goes next.

I tried for two months earlier this year trying to capture the light coming through the canopy and it just didn’t work. Everything is a result of where I am working. My studio was too hot to work in, and so I was working under a tree – it was a walnut, which had a range of different colours in the leaves – and I was trying to capture all those variations in colour and collage them together, all in ink, in different gradients. I tried black and then green and it just wasn’t working, so I slightly felt that I was trying to – I’m always trying to come up with new work, a slightly ridiculous pressure to put on yourself, really you should just give yourself more time, so now I have gone back to doing the tree shadows. So yesterday I completed three paintings, which was a relief, because I got a bit stuck for two or three months. I do want to come back to the light through the tree canopies, because it’s been an obsession of mine for ages, since I was a kid really, when you were lying on your back on the grass looking up into the leaves with the sunlight coming through, but I can’t capture the light at the moment with the medium I’m using, so that’s why I’ve started making etchings, because the whiteness of the paper and the black ink, which becomes very matt, seems to be doing the job.

What are the challenges of your way of working ?

The etchings came about through the need to fill the winter gap. I was drawing in the winter sun, but it didn’t cast a good shadow, which I hadn’t realised, because the angle of the sun was too low. And it was a really grey winter last year, so I was waiting for the sun that never came. I did try using a lamp in the studio, but it felt wrong. It was impossible to get the light at the right angle and it felt like faking it. I am interested in capturing an ephemeral moment, not a frozen moment that doesn’t change. I have tried working from photos of shadows I’ve seen when out and about and projecting them onto the wall of the studio, and again it just didn’t feel right. I wasn’t capturing that moment that the camera had captured. And I enjoy the process of being really spontaneous. Just yesterday I had a small window to work in because the clouds were coming, and I was moving around this mock orange branch, and then the sun went, which was my fault for taking too long, which takes me back to that whole thing of not thinking and just being in the process. Every time I overthink it, it feels like I could be on that painting for weeks, and I’m not really like that as a person, so it would feel unnatural to do that.

By working with the sun I have got to know more about the passing of time, changes in daylight and seasonal changes. So I now know that autumn is coming up to peak season, because you get those amazing long shadows, which I find quite exciting, alongside the anxiety of knowing that I’m running out of time. I did do some painting in Thailand last winter. Paintings of palm trees that just looked like palm trees, and I found that quite interesting, because I didn’t know the Thai landscape, I didn’t know Thai plants, and I realised I am happier painting the familiar. Someone asked me recently why I paint hazel, and it’s simply because it’s in the hedge at the back of my studio, and it’s abundant. When I came to your place, again it was just complete overstimulation. There was so much, and I didn’t know what to choose, and your garden is very much a changing landscape. You can leave it for two weeks and come back and there will be a whole different colour palette. So when I came to your garden it just felt wrong not to paint flowers, even though in my mind I thought, ‘No more flowers. I’ve painted enough.’ It was the first time I felt like I actually wanted to paint flowers again, because I was discovering new things again, So that is something I’d like to explore more in your garden, but I need to get more used to it, as it is a whole new territory.

You told me that painting in our garden has opened up a new way of working for you. How ?

Well, the summer we’ve had this year has been very unusual. We don’t usually get weeks on end when it is just sunny every day, and I just felt like I needed to mark that. To capture the sun, and capture the flowers. So I thought, ‘How can I do that ?. So what I have noticed about your garden is that it has a lot of different shapes. All the plants have their own identity, and they all hold their own in the beds, none of them get lost. So I wanted to capture the shape of the plants, but not in ink.

With the etchings I did last winter of leaves, you just got the silhouette, and so I tried painting the silhouettes of some of your plants directly from life, and I just didn’t like the feel of them, and then the light was so amazing that that became my focus. So I started exposing the shadows onto cyanotype paper, where you are directly capturing the light on the paper. I’d first done this a few months earlier and was really interested in the process, as it produces images that are almost like abstract paintings. In some you can tell what the plant is, but in others you can’t and I like that. So the first time I tried it in your garden I was too scared to get close to the plants in the beds, and so I took the deadheaded rose cuttings off the compost heap, because I could just put them onto the paper and allow them to fall in their own way without me arranging them. I also like that element of chance. And I was also very influenced by the things you have at your place. Quite a lot of elements from Japan, a lot of natural materials and a lot of craft. And I just felt that etching, which is a craft, was a more appropriate response to the site.

So I want to create a series from your garden, but I would also now like it to be a longstanding, seasonal thing. So this summer it has, so far, been about the roses, which were such beautiful, old-fashioned looking varieties. I would like to come back at harvest time and see if I can capture that, when everything is going to seed. And rosehips. I just really want to document the seasons, as I don’t think people look at things closely enough and I think, when you’re more in tune with the seasons, you understand the world and our place in it better.

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

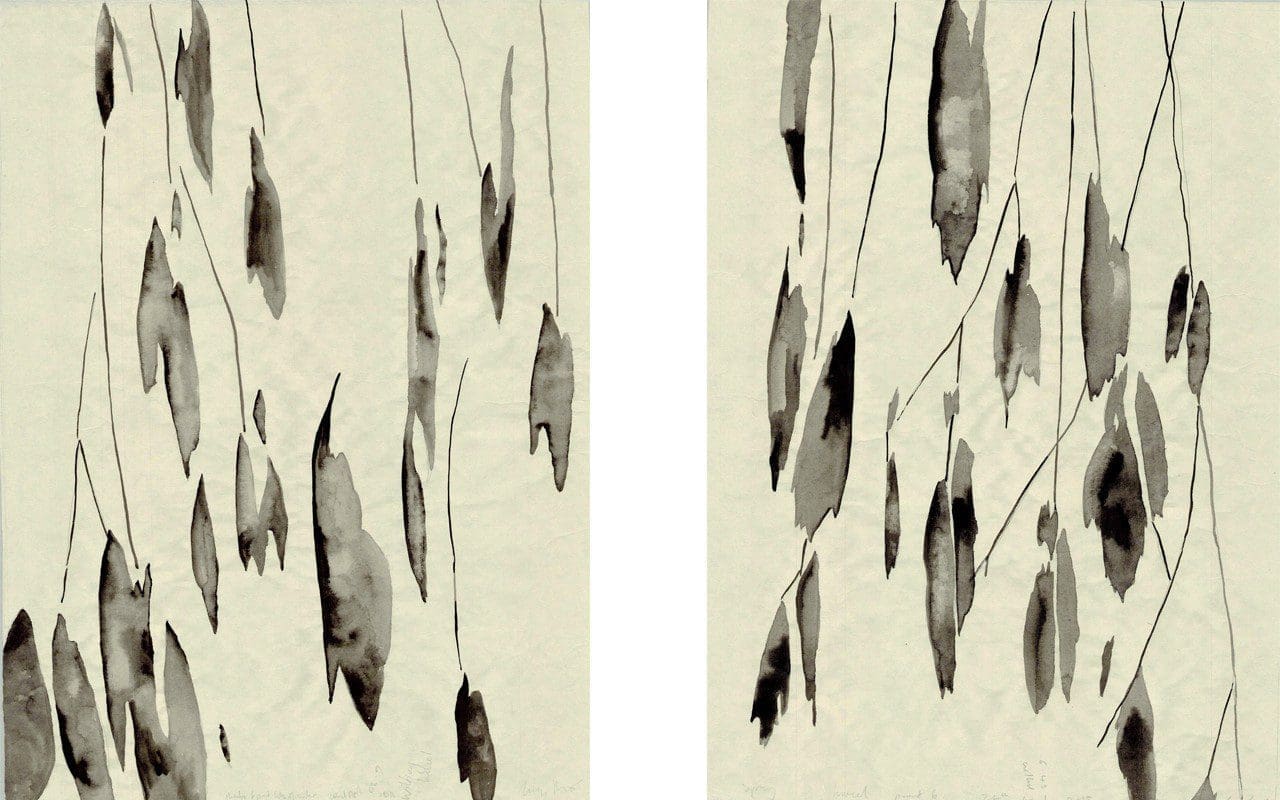

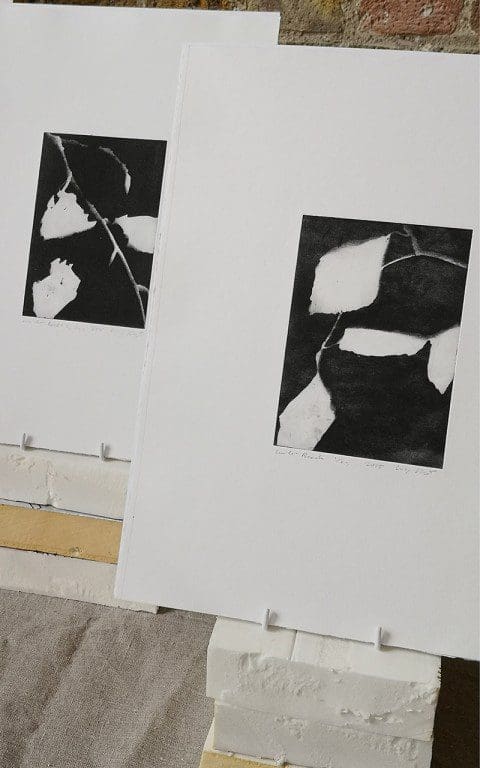

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

After last winter do you have a new approach for this coming winter ?

Yes, winter will be the time when I execute all of the etchings I am going to make from the cyanotypes taken in your garden. The process of creating etchings is quite time-consuming and complex, and it is still very new to me so I would like to spend more time getting more experience of that process. So at the moment I am just amassing lots of exposures so that I have plenty to work with later. And I am also going to explore some light and dark paintings of your garden from sketches I have made. Fingers crossed I am beginning to find a good seasonal rhythm for my work.

I’m also going to experiment more with photography, and explore the uses of light more and see where I can take it. As well as stillness I’m really interested in capturing the passing of time. For example the cyanotypes I made in your garden only needed a ten second exposure because the light is so strong there, whereas in my studio I need a fifty second exposure to create the same quality of image, but that longer exposure also captures that extended amount of time. I find that fascinating, and a route I’d like to explore. I also go to Westonbirt Arboretum in the winter, as there is always something out. Going there makes you realise how much there is to look at. There’s always something in season, or that has something in its branches to explore, and then you really are looking at winter. But I think your garden has a lot of winter interest, which I am looking forward to.

I also want to focus on the work without the pressure of a show, and just have a process for a while and see where things go, like the exhibition at the Garden Museum, who you introduced me to, and which came about very organically. I would like to be a bit more relaxed and take more time.

Do you have any burning ambitions for projects ?

I would love to be commissioned to create a stained glass window in a church. I’m not religious, but because I work so much with light, I could really see my work translating into stained glass effectively, with sun streaming through. I’d love to work with a craftsperson to do that. And I’d really love to create a design for the Chelsea Flower Show poster, which has always been something I’ve wanted to do. And I would love to do a residency in Japan.

Lucy’s work is available to buy from a catalogue on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs of Lucy and studio: Huw Morgan. All others courtesy Lucy Augé.

Published 25 August 2018

Today’s posy draws upon some of the fine detail in our fully blown August garden. A garden arguably never more voluminous and drawn together now with a growing season behind it. Look up and out and your eye can travel, for the grasses and the sanguisorba are asserting their gauziness. The first of the asters are beginning to colour, in wide-reaching washes that I’ve made deliberately generous. At this time of bulk and volume, however, it is also important to be able to look in and find the detail in something intense, finely drawn and requiring close examination.

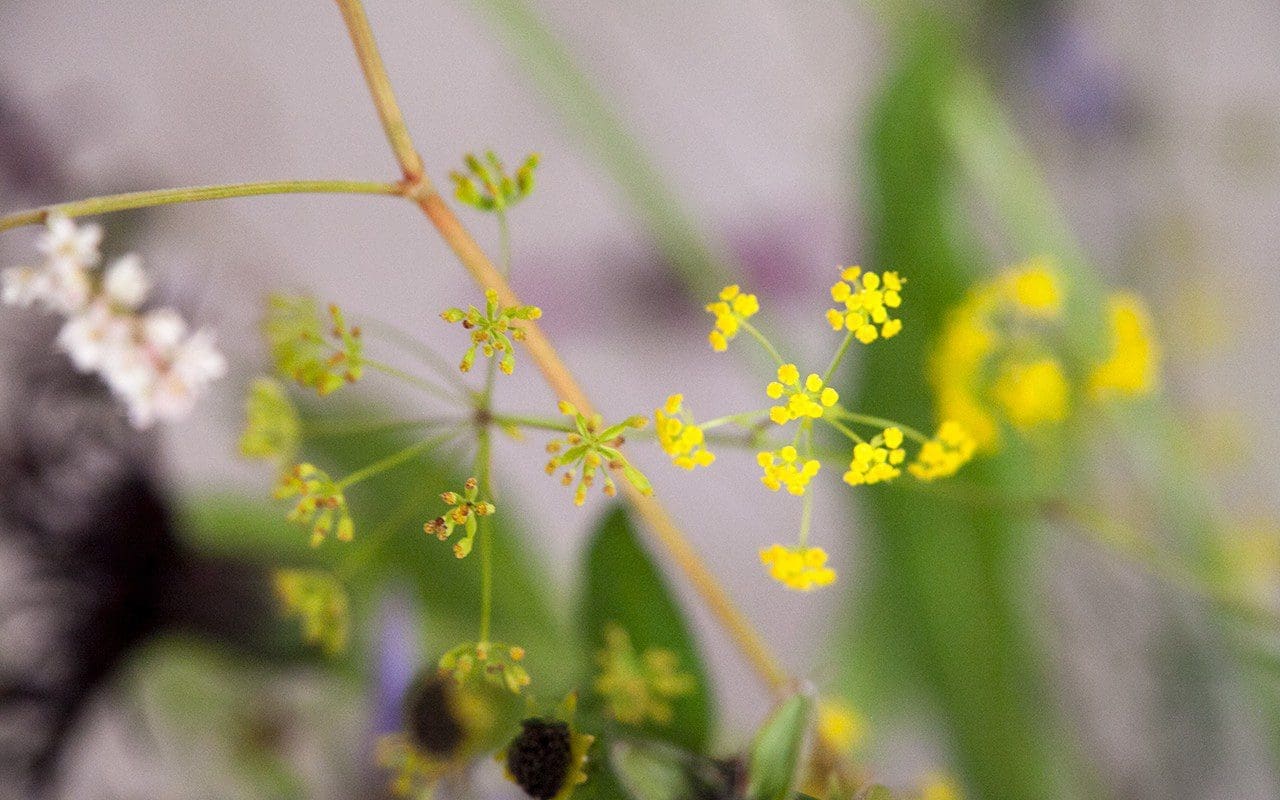

Most of the flowers in the garden here are deliberately small, so that they feel part of the place and cohesive with the scale of the surrounding meadows. Some, like the sanguisorba, appear en masse and register together to create a wash or a veil through which you can suspend an intensity of contrasting colour or screen another mood that appears beyond it. The Bupleurum falcatum, which has now seeded freely in the gravel garden, does just this in the posy to enliven the mood with it’s fine, acidic umbels. At another scale, the Fagopyrum dibotrys does the same in the borders, towering tall and creamy. This perennial buckwheat is prone to wind damage, snapping rather than flexing, but I have found it a sought-after niche close to the buildings to help to narrow the feeling alongside the steps. The scale of its flowers, and their airy distribution, is why it retains a feeling of lightness.

Bupleurum falcatum

Bupleurum falcatum

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Althaea cannabina

Althaea cannabina

Some plants are more interesting for having to find, but their subtlety requires careful placement. The Clematis stans was initially planted down by the barns whilst I was seeing what it was going to do here, but it has been good to have it closer for the detail in the flower is up to regular inspection. This herbaceous clematis is rangy when growing in a little shade but here, out on the blustery slopes, it makes a compact mound of a metre or so across. Prune it hard to a tight framework in February and it rewards you quickly with bright, expectant leaf buds and then foliage that is elegantly cut and not dissimilar to Clematis heracleifolia. In high summer, when the light levels change, it begins to produce clusters of powder-blue flower buds which taper and colour as they move toward flower. Reflexing just the tiniest amount to form a bell like a hyacinth, they have a delicate perfume, which is lost if you bury the plant too deeply in a bed.

Clematis stans

Clematis stans

![]() Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Earlier, in the heat, I was beginning to debate whether I’d take out the Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’, for it appeared to hate the brilliance of this summer and the exposure. Already a plant of some modesty, the relief of rain has them with flushed new growth to prove me wrong and it is a delight to come upon it, for it has to be found. The dark, filamentous flowers are as dark as blackcurrants, but combined with silvery Lambs Ears (Stachys byzantina), they are thrown into relief. The hunt is furthered by merging the groups with four-leaved black clover (Trifolium repens ‘Purpurascens Quadrifolium’) and Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. The clover is actually brown, and the potentilla punches colour strongly, but in tiny pinpricks that flash and then disappear as they open and close during the day. Walk the path in the morning and they will be blinking bright, but walk it again in the evening and they are closed, clocked-out for the day.

Pelargonium sidoides

Pelargonium sidoides

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

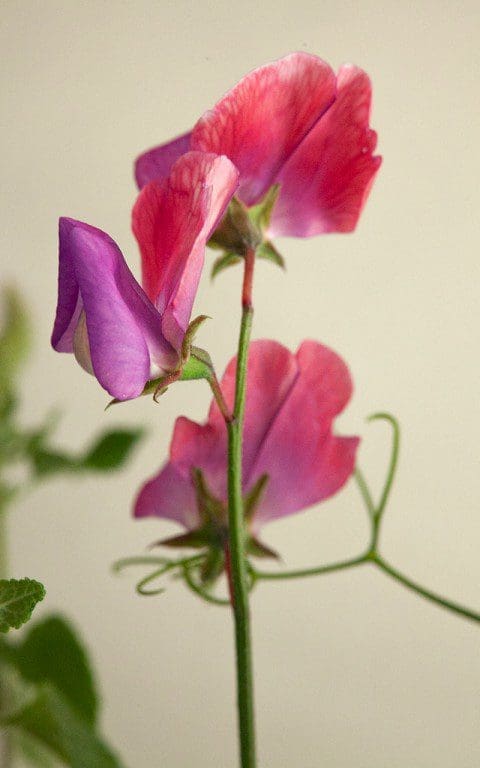

Over time, and now that the garden has grown and is demanding my attention, I’ve limited the number of pots up around the house. The Pelargonium sidoides are an exception and these are my original plants from what must now be twenty years ago. They have proved their worth despite their subtlety, but I help in having them close by the front door. They are grouped with pots of Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’. Early in the season and before they start their relay of flower, you might at first think that a potful of tulbaghia were chives, for the majority have a lingering garlicky perfume. The confusion of flower and savoury association is not always digestible, but this selection from Paul Barney at Edulis is an exception. The leaves do not smell and the perfume of the flower is delicate and sweet, particularly at night. They continue to push out flower from June until the frost, when I move the pot to the frame and deny it water for the winter and they survived last winter to prove their resistance when kept on the dry side.

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Succisella inflexa

Succisella inflexa

There are several new additions to the garden this year on which I am keeping a close watch and reserving my judgement, but Geranium ‘Sandrine’ looks promising. It is a little larger flowered than G. ‘Anne Folkard’, but it has a similar rangy habit and bright green foliage and will find its way amongst other plants, so far without dominating. The flowers, which with many perennial geraniums are bang and bust, do not come all at once, but stagger themselves throughout the summer. This makes them more precious and they pulse with their darkly-veined centres. Succisella inflexa, a Balkan perennial, is entirely new to me, but this looks good for being so late in the season. Finely elongated foliage scales the stems, but stops to leave the thimbles of pale lilac flower hovering at knee height. It has a similar presence to Devil’s-bit Scabious, which is flowering now too in this window between summer and autumn. We will see if it comes back with good behaviour next year, but for now I am watching closely.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 18 August 2018

Whether it’s fish and chips after a day on the beach, calamares fritos at a Spanish bar or Indian pakora with an ice-cold Tiger beer at a festival, deep fried food is something that always tastes better outdoors and when the weather is hot.

In Greece recently I was staying with friends who, in late June, were already struggling to keep up with their courgette glut, so for lunch one day we decided to make kolokithokeftedes, the traditional Greek courgette fritters. Courgettes are coarsely grated, salted and then squeezed to remove as much water as possible, before being mixed with onion, garlic, feta, egg, breadcrumbs, dill and mint. Traditionally shaped into patties and shallow fried, they can be a little heavy, so my host decided to put loose spoonfuls of the mixture into deep boiling oil so that the shards of onion and courgette that made their way free of the mass became crispy and a deep, caramelised brown. They came out looking like tiny deep-fried, soft-shelled crabs. Served with a bowl of cold, garlicky tzatziki, six of us devoured about forty of them in quick succession.

In Japan, of course, it is tempura that fulfils this role. It is no surprise to learn that the technique of deep frying batter-coated fish and vegetables was brought to Nagasaki by the Portugese in the 16th century. Peixinhos da horta is believed to be the original dish that inspired a way of cooking that we now primarily associate with Japanese cuisine. These ‘little garden fishes’ are green string beans, coated in batter and deep fried, and were eaten in Portugal during Lent, when meat was off the menu. The Japanese took this idea and ran with it, and now tempura describes the method of cooking any fish, meat or vegetable in this way.

One of our favourite places to eat when in London is Koya Bar, a tiny Japanese restaurant in Soho, where fast-cooked food is prepared in front of you behind a long seating counter. While the queue to get a table can sometimes seem intimidating, the turnaround is so fast that waiting in line for 30 minutes is a small price to pay for food this delicious. It is the most authentic Japanese eating experience we have had outside of Japan. Although they specialise in udon noodles, there is always a blackboard of seasonal specials on offer and, of these, it is the kakiage tempura that we order without fail whenever we go. Kakiage tempura differs from regular tempura in that it is a mixture of sliced vegetables (sometimes combined with fish) in batter rather than the individual pieces of fish, crustacean and vegetables that we are more familiar with. Seasonality is key and, at Koya, they can be made of anything from wild carrot with carrot tops to broad beans and peas or squid and chrysanthemum.

We are now in the midst of our courgette glut and looking for new ways to use them as often as possible, while our sweetcorn is challenging us to eat it quicker than it becomes starchy. I have grown ‘Double Red’ this year, a new variety with seed from The Real Seed Catalogue, who sell some of the most interesting vegetable varieties in the country. The plants are highly decorative with stems and husks stained a deep purple-red and cobs of dark burgundy, almost black, kernels, which are almost too beautiful to eat. They have made a good partner to our ornamental red and tan amaranth this year. We have also just lifted all of our onions and so the combination of vegetables here reflects what is best to eat at this very moment. I could also have used green beans, carrots and beetroot or, later in the season, pumpkin, sweet potato, mushrooms, celeriac, kale or salsify. You can also add any herbs that you like to the mix. Here I have used the traditional purple shiso (Perilla frutescens var. crispa), which is used to impart the pink colour to umeboshi plums. It has a flavour somewhere between aniseed and basil. Dipped into batter and fried at the end of cooking the leaves also make a beautiful garnish.

Sweetcorn ‘Double Red’

Although there is a plethora of recipes for tempura batter using either whole eggs or whisked egg whites, I have found that the simplest batter of just flour and water makes the crispest coating. However, there are a few golden rules to ensure that your tempura turns out as well as possible. Firstly, all of the vegetables must be cut to a size where they will cook in the same time. It is traditional for the vegetables to be coarsely julienned or grated. Secondly, get your oil hot enough to cook before you make the batter. It should be between 170°and 180°C. Thirdly, the batter should be as cold as possible, and must not be over-mixed or whisked which stretches the gluten and makes it tough and chewy. Chopsticks are used traditionally and it should have lumps of flour in it. Fourthly, before placing the batter-coated vegetables in the oil, allow as much batter to drain from them as possible. This ensures the lightest coating and avoids a doughy centre. Fifthly, only cook a couple of spoonfuls at a time, so as not to crowd the pan and lower the temperature of the oil. Sixthly, use a small wire strainer or slotted spoon to remove any overcooked bits of batter from the oil between batches to avoid them flavouring the oil and attaching to the next lot of fritters. And finally, do not be tempted to ‘worry’ the fritters in the oil, be patient and leave them be until they are ready to turn, or the batter will not have cooked and they will fall apart.

It is customary to serve tempura with a simple dipping sauce of dashi, soy sauce and mirin, but the lemon and miso sauce here, adapted from a recipe by Elizabeth Andoh from her excellent book of Japanese home cooking, Kansha, complements the richness of the fried fritters perfectly.

Purple shiso

Purple shiso

INGREDIENTS

350g courgette, coarsely julienned or grated

2 large sweetcorn cobs, shucked

1 medium red onion, about 175g

8 large and 6 small shiso leaves

Sea salt

Sunflower or rapeseed oil

Batter

175ml iced sparkling water

65g self raising flour

65g cornflour, plus 1 tablespoon more

A few ice cubes, 4 to 6

Dipping Sauce

3 tablespoons white miso

3 tablespoons lemon juice

Finely grated zest of half a lemon

1 tablespoon maple syrup or lightly flavoured honey

1 tablespoon mirin or sake

Makes about 12, enough for 6 people

METHOD

Put the courgette into a sieve and sprinkle lightly with sea salt. Use your hands to mix the salt in well and then leave to drain over a bowl for 20 to 30 minutes.

To make the dipping sauce, put the miso and lemon juice in a small bowl and stir well. Add the maple syrup or honey and mirin and stir well again. Add the lemon zest and stir again. Transfer to a serving bowl.

Using a very sharp knife shave the corn kernels from the cobs over a bowl. Slice the onion in half down the centre and then cut each half across the grain into crescents the thickness of a coin. Separate the onion crescents and add to the bowl of corn.

Take small handfuls of the salted courgette and squeeze hard to remove as much water as possible. Add to the bowl of corn and onion. Cut the eight large perilla leaves into fine ribbons and add to the bowl. Using your hands, mix all of the vegetables and herbs together until the courgette strands are separated and all is well combined. Sprinkle over the one tablespoon of cornflour and toss with your hands again until everything is lightly coated. This helps the vegetables to stick together when fried.

Pour the oil into a medium-sized (25cm), deep-sided frying pan to a depth of about 2cm. Put over a medium heat until the surface begins to shimmer. Turn the heat down a little and make the batter. Put most of the iced water and some ice cubes into a bowl. Sift the two flours onto the water and then quickly mix together. The batter should be the consistency of single cream and just coat your finger. If it is too thick add more iced water. Turn the heat up under the oil and, when just smoking, test the temperature with a few drops of batter. It should sink and then immediately rise to the surface and puff up.

Pour two thirds of the batter over the vegetables and mix quickly until everything is lightly coated. Add a little more if you think it needs it. However, you may not need to use it all. The vegetables should not be swimming in batter. Using a tablespoon and a fork, take a scant tablespoonful of the vegetable mixture and hold it above the bowl, allowing most of the batter to run off. Then slowly place the vegetables into the hot oil, using the fork to quickly spread them out so that you have a thin fritter about 8cm in diameter. Now wait 30 seconds for the underside of the fritter to cook, before using two forks – or chopsticks – to carefully turn the fritter over. Cook for another 30 seconds until the other side is cooked and lightly coloured. In a medium-sized pan you should aim to cook no more than two fritters at a time, always allowing the oil to return to temperature before frying the next batch.

Remove the fritters from the oil with chopsticks or a slotted spoon, and hold them above the pan to allow as much oil to drain from them as possible, before transferring to a hot plate lined with absorbent paper. You can now either choose to serve them as they come from the pan or put the plate into an oven heated to 100°C to keep warm, while you cook the rest of the mixture.

When all of the mixture is cooked transfer the fritters to a clean plate. Quickly dip the remaining shiso leaves in the batter and fry until crisp. A matter of seconds. Remove and drain quickly on absorbent paper, then use to decorate the plate of fritters. Serve immediately with the dipping sauce.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 11 August 2018

In the eight years we have been here, the landscape has never bleached to this degree. In the most part our West Country moisture has kept the fields green, but the heat and month or more without rain has had its influence. A blond horizon backdrops the garden where the Tump hasn’t re-grown after the hay cut, and the high fields around us throw a September light which, at the beginning of August, has been disorientating.

Past summers have only required me to water once or twice during the season, but this year the new planting has needed it more often and I have worked the beds with a fortnightly drench to encourage the roots down by soaking each pass deeply. The watering has done nothing for the fissures which have opened up in the beds. Some are wide enough to put your hand down to the wrist and have got me thinking that, if I had the time, this would be a perfect way of working a summer injection of humus deep into the ground, if I could feed it into the cracks. It would plug the gaps that sometimes run straight through root balls and help to protect roots which must be feeling the drought more directly for this exposure. Deep in the beds, where the planting is already closed over, they worry me less, but in the new planting where the local microclimate provided by companionship is not quite there, I am seeing the damage.

Those plants that are adapted to a hot, dry summer have shown their roots in simply not flinching and the thistles have been notable. Miss Willmott’s Ghost, the biennial Eryngium giganteum, is luminous in the truest sense of the word. Firing starry outbursts amongst the Bupleurum falcatum the growth is platinum white in bright light. This is only the second or third generation of self-sown seedlings and, so far, the volunteers have not become a problem in the gravel garden. I have had them take over in thin ground, where they have seized a window amongst perennials that have not taken to the conditions as heartily, so we will yet see if they are going to make a takeover in the gravel by the barns. If they do, it will be where the seedlings find their way into the crowns of perennials that are slow off the mark in the spring. Like a wedge splitting a boulder, they can, and do, have their influence in their pioneering nature.

Eryngium giganteum, Bupleurum falcatum and Crambe maritima

Eryngium giganteum, Bupleurum falcatum and Crambe maritima

Look closely and the thistles are magnets for wildlife. The hum of the bees on the eryngium is audible long before you see them, and the butterflies are now working the platforms of nectar that are obviously suspended high in the artichokes. We have a variety from Paul Barney of Edulis Nursery called ‘Bere’ and those that escaped the harvest – within a week they are suddenly too tough to eat – are now in flower. Though this year they must be a foot shorter for the drought, they still rise above the trough behind them and draw the eye through the gauziness of the herb garden. They have had no water for they are adapted mediterraneans and follow the rainfall with leaves that flush in the autumn and spring.

Right now, the neon-violet buzz of flower has taken all their energy and we have cleared the lower limbs of old leaves to enjoy this moment and not be distracted by tattered yellowing growth that is obviously no longer necessary. Cynara cardunculus (Scolymus Group) (main image) is spectacular in every way, each plant needing a good square metre to reach up and out. When the flowers dim and I start to see September regrowth at the base I will fell the lot to put the energy into new leaf, rather than it going into seed production, so that we have them during the winter. A mild one will see a mound of new foliage sail through unscathed. A silvery architecture in the bare kitchen garden.

Though I could write at length about the other thistles that I have invited into the garden, the notable one that rises head and shoulders above the rest is Cirsium canum. Stand beside it and this Russian native will dwarf you, literally, the bright violet-pink flowers teetering on tall stalks just out of reach. I suspect, if I had not watered the perennial garden, that the foliage would have burned more than it has, for it is fabulously lush in the first half of the summer. Like a giant awakening, the energy in its new growth is audible in foliage that is shiny and squeaky with life when you corral it into hoops in May to prevent it from toppling. I do not know, if one was to grow it on ground that was less retentive, whether it would be lesser in every way and need less staking. I also don’t know yet if it will be a seeder. Derry Watkins of Special Plants says her plants haven’t seeded. Yet. Just in case, I cut them to the base last year after flowering having been stung previously by Cirsium tuberosum when I was looking for a thistle that would do the same job. I think I will do the same this year if they won’t leave too much of a hole in the garden around them.

Cirsium canum

Cirsium canum

Cirsium canum

Cirsium canum

Cirsium tuberosum

Cirsium tuberosum

Cirsium tuberosum

Cirsium tuberosum

Though Cirsium tuberosum is similar in appearance, being more glaucous and less glossy, this Witshire native is, in my opinion, not a plant to be trusted in a garden. Given open ground and a window of opportuntity, it proved itself to be a monster in my stock beds. The wind-blown seed parachuted some distance and, though the seedlings were easy and graphically visible in their lust for life, the unseen few soon wedged their way into the crowns of perennials to send down taproots that were all but impossible to remove and top growth that rejoiced in being alive. When I was preparing the new garden, I jumped my stock plants of them into the rough grass that lines the ditch and here the competition has seen them in check and in balance. Stepping through meadowsweet and willow herb they look good in appropriate company and your eye can travel from the Russians in the garden to the natives in the ditch and be happy, so far, in the knowledge that each has found its place.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 4 August 2018

When we arrived here eight years ago, the fields lapped up to the yard at the front. Immediately to the west of the house a run of increasingly decrepit lean-tos made from a haphazard mix of cinder block, brick, stone and corrugated sheeting extended a semblance of domesticity along the slope. A rubble wall held back the track above and, along it, the structures made their way out towards the barns in stops and starts that charted their thrifty evolution; a scullery, an almost outside loo in a stone lean-to, then through a door into the original bathroom. Stand up washes at the sink in the winter, surely, as there was no evidence of heat. A recycled Victorian door then opened into a corrugated tin building where the coal had been stored and then finally, built onto the front of this, the piggery. Every room had a raking floor, pitching at some degrees down the slope. A seedling oak sprung from the brick floor of the coalhouse, the holes under the doors obviously big enough for squirrels or a rat, perhaps, who was planning a return visit, but never made it.

Our first project, the kitchen garden, lay beyond the reach of the lean-tos up around the barns. Several years ago we levelled the ground here in order to make the gardening easier. Two staggered troughs went in on this datum at the same time, echoing the horizontal line of beech on Freezing Hill in the distance and creating an informal gateway to the kitchen garden. By separating the kitchen garden off, when the lean-tos were demolished, we had a new garden space between the end of the house and the troughs. During building it was an area we had to traverse with caution, as it became more and more building site, with deep ruts, bonfires, rubble piles and the remains of the slope.

Although we had to knock down the lean-tos, we repaired and rebuilt the stone building that had previously been the pantry. The rubble wall now stood in splendid isolation, naked but shadowed with the ghosts of each of the buildings that had run along it. The tiles of the old bathroom, the blackened coal house and then, finally, a raggedy end up by the piggery. Word had it that ‘Mother’ had once had a vegetable garden on these slopes immediately beyond the piggery and, with the buildings gone, it was clear that this would be the space for the herb garden. A concrete pad was poured alongside the rubble wall in preparation for an open barn that would become our inside outside space and, in the summer of 2016, with the builders gone, we made a start to reclaim the ground.

Calamintha nepeta ‘Blue Cloud’

Calamintha nepeta ‘Blue Cloud’

Ballota pseudodictamnus

Ballota pseudodictamnus

A cut was required to make the level between the house and the troughs, and the fill from the cut was used to extend the level out and down to form banks that rolled into the field. Where the rubble wall ran out, we extended a breezeblock wall to hold back the banks that had been held together with sheet tin and bedsteads, and the remains of a hedge that was mostly elder and bramble with a couple of sickly plums. I replaced the hedge on top of the new wall, mingling hawthorn with eglantine for its scented foliage, and with wild privet and box for evergreen. Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ – a short growing form of our native honeysuckle selected by Roy Lancaster, has been added along its length. The wall faces south and heats up in the day to throw the perfume back at night. I planted wild strawberries at the base of the hedge so we have easy pickings at shoulder height on the way to the steps. The perfume from the strawberries has been incredible during this recent run of long, hot days.

A set of new cast concrete steps sit half way along the wall and flare at the top where a landing forms a viewing platform. From here you can survey the kitchen garden to the west and this new space alongside the house. The concrete pour into a shuttered wooden framework took some engineering, but the steps have weight and their gravity is needed where they sit in the space between the troughs. We grow artichokes and the rhubarb here. Plants that need room.

The herb garden was a working title that has stuck. The actual herb beds are a pair of narrow raised beds up by the open barn where we can easily pick the annual herbs that like the morning shade thrown by the building. Coriander, dill, wild rocket, coriander, chervil and parsley, but not basil which needs the all-day heat that lies beyond in the kitchen garden. Further out the perennial herb bed gets the sun and provides us with sage, rosemary, thyme, marjoram, tarragon, summer and winter savory, sorrel and the like. Mint is contained in a pair of old zinc washing dollies in the shade of the building, where it stays lusher and leafier.

Lavandula x intermedia ‘Sussex’, bronze fennel (left) and Opopanax chrironium (right)

Lavandula x intermedia ‘Sussex’, bronze fennel (left) and Opopanax chrironium (right)

Basil ‘African Blue’

Basil ‘African Blue’

The extent of the planted area between here and the troughs had to be carefully re-soiled once the cut into the land was made into subsoil. I left it fallow the winter before last, as I wanted to see how easily it drained, since the ‘herb garden’ was where I wanted to grow my lavenders and salvias and other plants that associated well alongside them. I am pleased I did, because while the soil was settling down it drained very badly, puddling in the winter. I thought I was going to have to reconsider my palette, but couldn’t think of anywhere the lavenders would feel as right. It was only when the spring sun dried the soil out and natural fissures opened up in our clay subsoil that it started to behave as I wanted it to.

I planted last spring, late in April once the first phase of the main garden was in and mulched. The cut-leaved Ficus afghanistanica ‘Ice Crystal’ was planted close to the bottom of the steps to create a narrowing and a shaded exit point. Though not selected for fruit – they are small and sweet when they come, but require prolonged heat to ripen – I like the fineness of the dissected foliage immensely and, although I have never seen a large plant, I expect it not to take over as figs tend to when they like you. The willow-leaved bay, Laurus nobilis ‘Angustifolius’ anchors the inside corner nearest the house. With elegant, narrow foliage this bay also has a lightness about it. I will keep it loosely clipped into a dome at about shoulder height when, one day, it assumes its position.

I trialled three different lavenders in the old garden in anticipation of this planting. Lavandula x intermedia ‘Grosso’, a variety used in perfumery in France for its high production of essential oils. I liked it very much. It has good, strong colour and certainly good perfume, but the plants splayed under their weight when in full flower. The best time to harvest lavender for the oil is when the first flowers on the spike are just out, so good for perfumery, but not so good for the garden. L. x intermedia ‘Edelweiss’ came a close second with a camphor tang to the perfume and beautiful white flowers that were much loved by the bees, but they proved to be erratic here, with too many plants failing in winter making me lose confidence in committing to it. Our wet West Country weather was probably their downfall. Not L. x intermedia ‘Sussex’ which, though not as dark as ‘Grosso’, is good in every other respect. Tall, long flower spikes and a good form to the plant that, so far, has proven reliable here.

Salvia greggii ‘Blue Note’

Salvia greggii ‘Blue Note’

Echinops ritro ‘Veitch’s Blue’

Echinops ritro ‘Veitch’s Blue’

Salvia uliginosa

Salvia uliginosa

So, the lavender form the backbone of the planting, thirty plants staggering their way across the space, but with openings left for light-footed emergents; Verbena bonariensis – only here and nowhere else for fear of overuse – and bronze fennel, just five plants to keep the airiness in the planting. I’ve direct sown the acid yellow Ridolfia segetum, bone white corncockle Agrostemma githago ‘Ocean Pearl’ and white Ammi majus to lighten the palette. The sparkle is important amongst the mauves. A darker counterpoint is provided by the purple spires of Basil ‘African Blue’, pot-grown nursery plants that we plant out yearly as annuals.

Rising up in this second year are the Opopanax chironium. A herb used for the incense resin that is extracted from the dried sap, this is another of the many umbellifers gifted to me by Fergus Garrett at Great Dixter. Though they have yet to flower here, the Giant Fennel, Ferula communis, are planted towards the edges of the bed so that it doesn’t overshadow the lavender with its early growth. I hope to see them bolt skyward next year, but for the early part of the growing season their netted leaves have been wonderful.

I wanted this planting to have unity but, like the cloudscape it resembles, I also wanted to be able to find the shifts in tone and form. The palette of recessive mauves and blues also allows us the long view here, which is most important because the planting is all too often eclipsed by what is going on in the sky. I have built on the insect life that the lavender attracts with Nepeta ‘Six Hills Giant’, which is alive with bumblebees from the moment it starts flowering in April. The smaller in scale Calamintha nepeta ‘Blue Cloud’ is delicious by the path where, if you brush against it, you are rewarded with fresh menthol mintiness.

Agrostemma githago ‘Ocean Pearl’

Agrostemma githago ‘Ocean Pearl’

Linum perenne

Linum perenne

Dianthus ‘Miss Farrow’

Dianthus ‘Miss Farrow’