Clare Melinsky is a linocut illustrator, who created the cover and monthly chapter plant illustrations for Natural Selection, Dan’s new book which is being published by Guardian Faber on May 4. Clare was chosen for her keen eye for botanical detail, her innate understanding of plants and her talent for graphic simplicity.

You originally studied Theatre Design at Central School of Art. How did the change to linocut and illustration come about ?

In Theatre we had a seriously practical course with actual budgets for putting on productions with real actors. We stayed up all night sewing on buttons and painting scenery. It taught me about deadlines and responsibility, skills you would not normally associate with an art school education. And I also learned that the theatre world didn’t suit my temperament.

In the Foundation year at Central I had enjoyed a week of printing linocuts, and after I left college I did some linocut printing on textiles. A publisher friend, Richard Garnett at Macmillan, asked if he could use one of my motifs on a book cover: so I discovered the world of editorial illustration. At the same time Mark Reddy, a contemporary at Central, was starting out in advertising, and he, too, commissioned a linocut image from me. So I also discovered the existence of illustration in the commercial world. Both were much more financially rewarding than printing bedspreads and cushion covers. Light bulb moment: I would be an illustrator.

Illustration for Tesco wine label

Illustration for Tesco wine label

There is clearly a connection between theatre and the narrative complexity and framing of many of your illustrations. How do you go about identifying the elements required for a commission and then putting them together in a coherent whole ?

I have always enjoyed the research part of a job. As a student I spent many happy days ordering up stacks of dusty books from the card index at the V & A library, and sketching in the galleries. Now I have my own collection of reference books which I know inside out.

I like to get authentic detail of the time and place, and look for telling motifs rather than invent my own. For example the figure of Juliet on the Penguin Shakespeare cover is based on a tiny detail in an Italian fresco that I came across when looking at contemporary images, a lady leaning on a balcony: there was my Juliet. Having identified the elements, I then apply structure and colour and contrast to the specified size and shape in the short time available. Rather like garden design, I suppose.

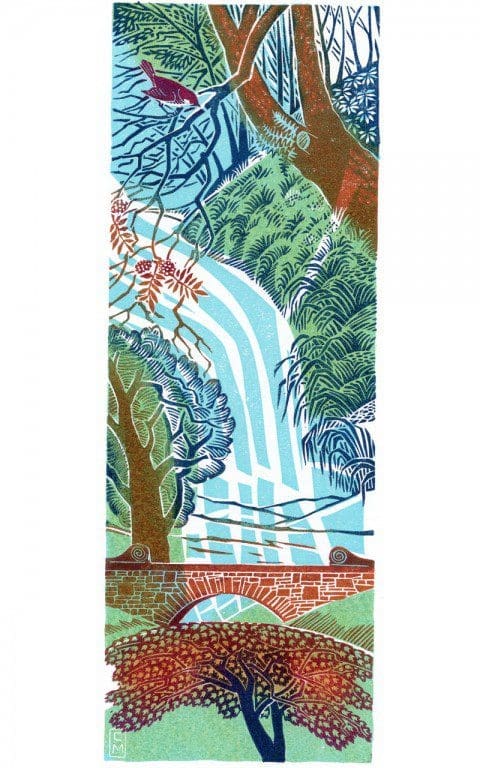

The Holm

The Holm

You have said that your work is inspired by historic woodcuts. I can see echoes of Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and others in your work, and many of your plant portraits have a distinctly Japanese feel to them. Can you tell me about artists that have inspired you ?

I am a big fan of Bawden and Ravilious. I first came across their work at an exhibition at the Tate in 1977: The Curwen Press collection. It was a seminal moment. Before that I had studied technique by looking at Bewick’s wood engravings (1800-ish) and Joseph Crawhall’s popular woodcuts from the 1890’s.

Some years later I was given a secondhand book of mid 20th century Japanese prints collected by an American, Oliver Statler, when he was stationed in Japan after the war. These prints are known as Hanga: a revelation to me. A whole new way of looking at relief prints. More recently my daughter Jessie spent two years in Japan on a Daiwa scholarship doing part two of her architecture degree. So I was able to visit her in Tokyo, and travel during the traditional cherry blossom festival time which added a lot to my appreciation of Japanese style, and prints in particular.

Seeing the gardens in Kyoto was so exciting, in the context of their temples. Our accommodation in Kyoto was in a monastery, and we were expected to meditate in the temple for an hour before breakfast, which was mushroom broth. In the hillside moss garden, we saw the monks (or were they gardeners?) picking fallen leaves out of the moss to keep it pristine.

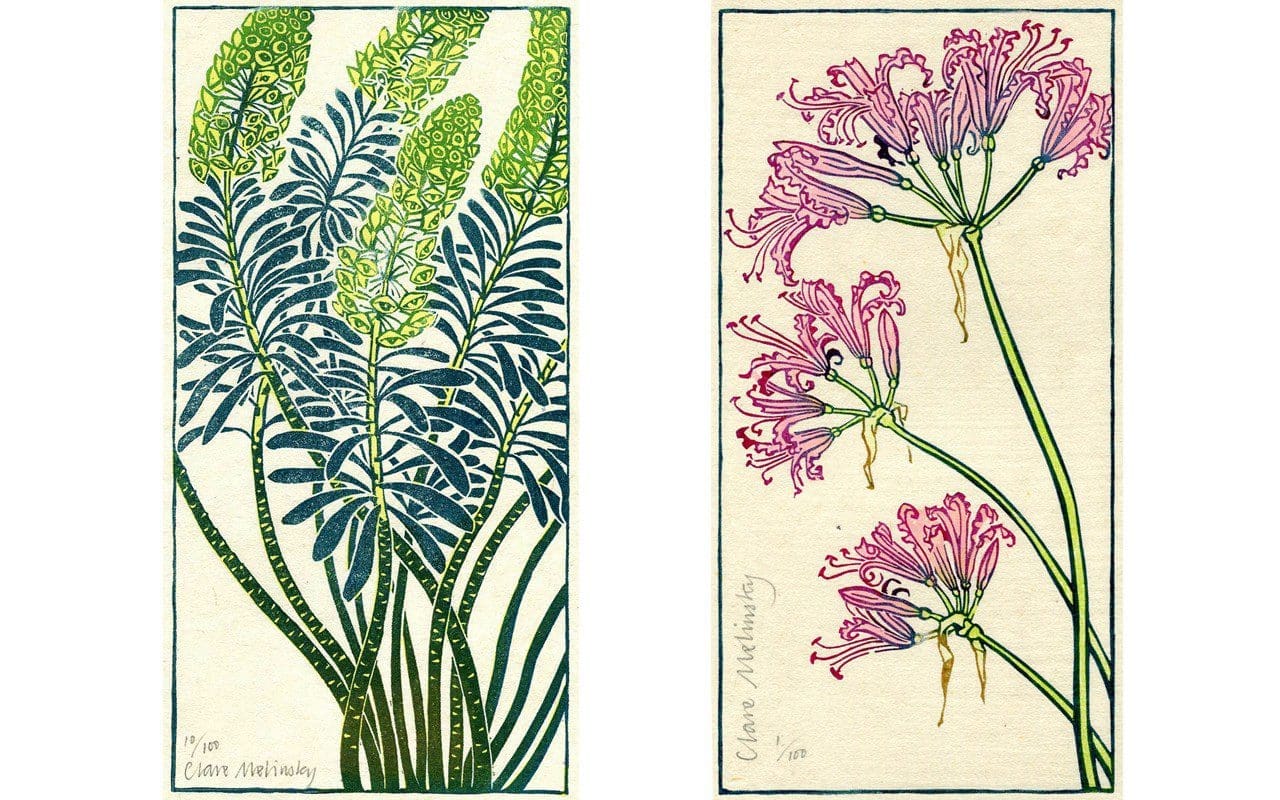

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

You have said that your garden can easily distract you from your linocuts. Can you tell me about your garden and what it means to you personally and professionally ?

After graduating I still lived in London. But my partner and I spent the summers with his sister’s young family in south west Scotland on their smallholding: we decided that was the life for us too. We started with twelve boggy acres at 1000 feet (300 metres). That means high up in the hills. We were the last house, six miles up a single track road in Dumfries and Galloway, south west Scotland. Sheep, goats, a dairy cow and calves, hens, two children, geese, a pony… we were very ignorant but it was a good life and I have no regrets.

It was originally my partner who was the gardener: we had a huge and productive veg plot, organic of course, with a big input of muck from the beasts. Very good soft fruit too. It was such a good lifestyle choice, because it meant that we could afford to live off my earnings in the early years. I could never have earned enough as an illustrator to support a family, if I had stayed in London.

After thirteen years it was time to move somewhere more sensible. Not far from our first house, but a bit nearer sea level and civilisation, we now have just one cat and a garden, with a wood at the back of the house and a burn running alongside. Lots of hardy perennial flowers and a small fruit and veg plot. Whenever the sun is warm I drop what I am doing and go outside with my gardening gloves on for a couple of hours. The climate here is so wet that you absolutely have to enjoy any fine weather when it comes.

Clare’s house and garden in early April

Clare’s house and garden in early April

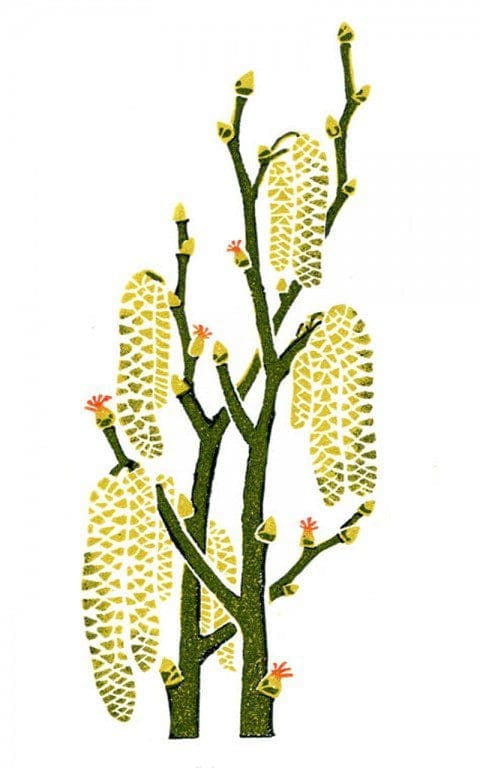

Hazel catkins

Hazel catkins

In the woods behind Clare’s house

In the woods behind Clare’s house

You work across a wide range of different media including book covers, stamps, product packaging and editorial. However, it seems that you include plants and landscape in your illustrations whenever relevant and possible. Can you tell me how your garden, landscape and plants inspire your work and influence the commissions that you accept ?

It’s what I see when I look out of the window. Most of my holidays are actually in cities by way of contrast: visiting my son Tom who lives and works in New York for example. I accept most commissions that come from my agent if I have the time: each job stimulates new ideas and creative development.

Gardening wasn’t a memorable part of childhood. I do remember individual plant experiences: a sea of lupins, as tall as us children, blue and pink and mauve, at the foot of the sand dunes on the Norfolk coast where we spent our summer holidays. A ravishing philadelphus enveloping the shed when I wheeled out my bike to cycle to school. A cataract of wisteria on an old rectory we used to visit.

My favourite toy at one time was a Britain’s Miniature Garden: little brown plastic rectangles and semicircles were the flowerbeds, dotted with holes into which you could push different clumps of coloured plastic flowers. You could buy individual flat-pack trees ready to assemble. Cardboard flagstone paths and rectangles of green flocked card with mowing-striped pattern. Little plastic rockeries and a pond and stone walls. I would save up my meagre pocket money to buy a new pack of plastic hollyhocks. Maybe that’s why I now have no hesitation in digging up a whole clump of perennials in full flower and replanting, if I decide that something is in the wrong place.

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Tulips

Tulips

Given the breadth of your commissions do you have a favourite subject matter ? Which appeals to you most ?

My agent comes up with very varied jobs – and I like that. I was so lucky to be invited to join the Central Illustration Agency when Brian Grimwood first started it. It is the one thing that makes it possible for me to live in the country, and still access the world of work in London. There is no continuity to the work, it is completely unpredictable what people ask for. The client has chosen me because they like my linocut style. So it is often more of the same. Since I finished your book I have done images for food packaging for Waitrose, a folk tale illustration for Britain magazine, and some labels for a local cider maker. Sometimes it all goes quiet and I don’t get a job for six months.

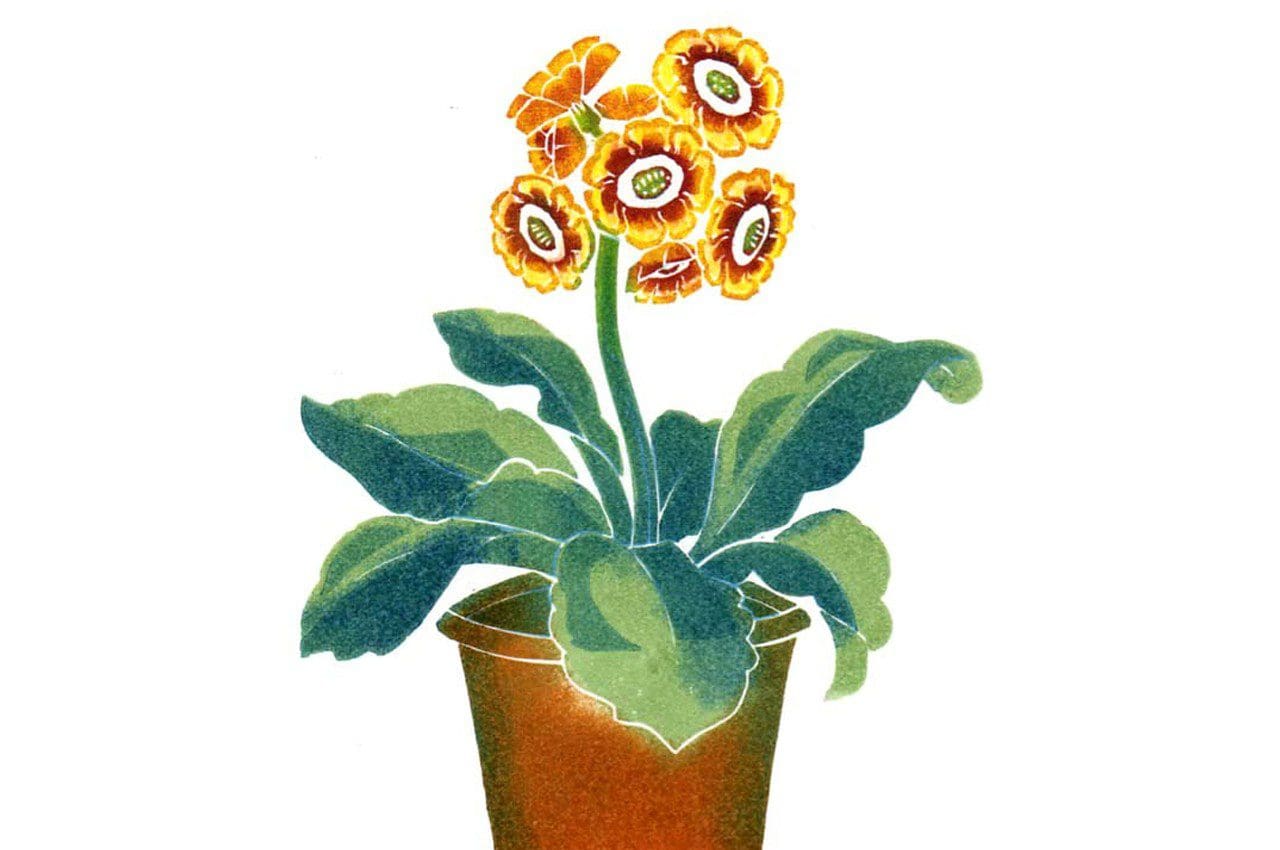

Primula auricula

Primula auricula

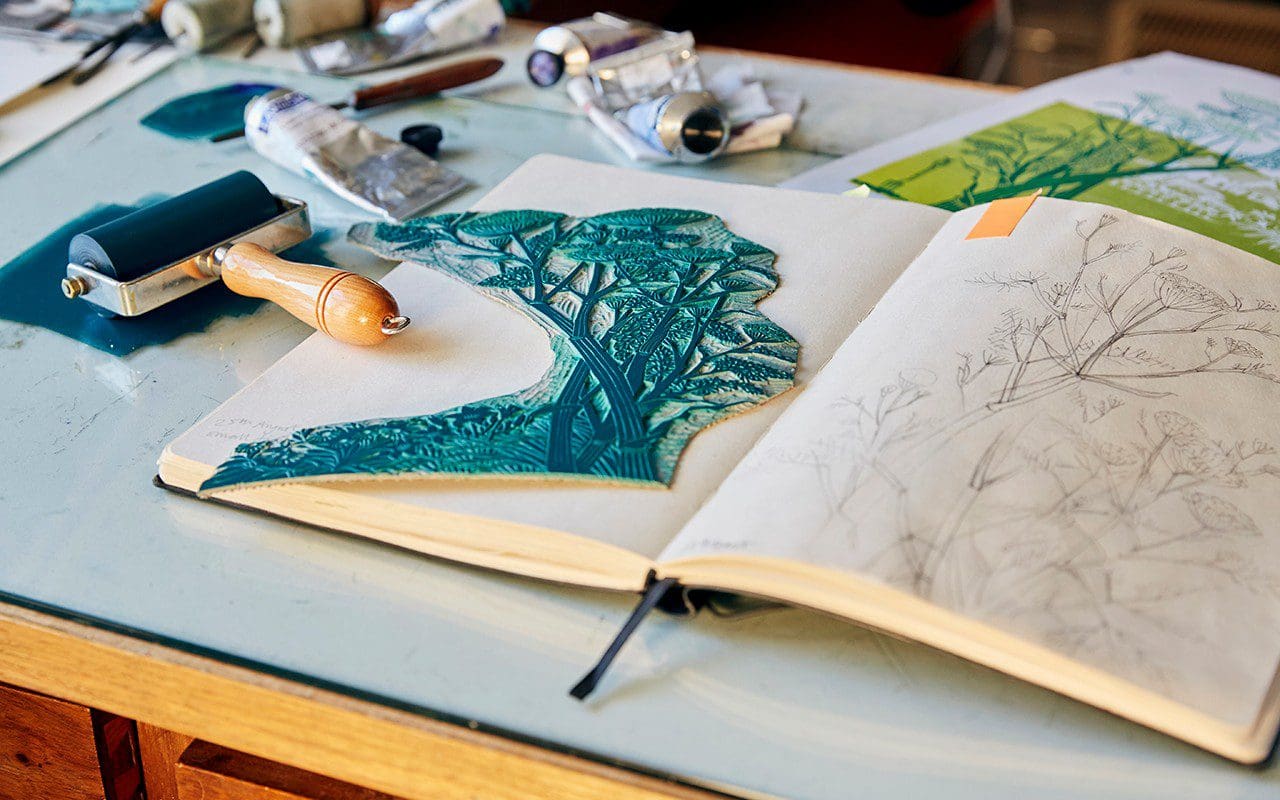

Can you explain your design process from sketch to finished print ?

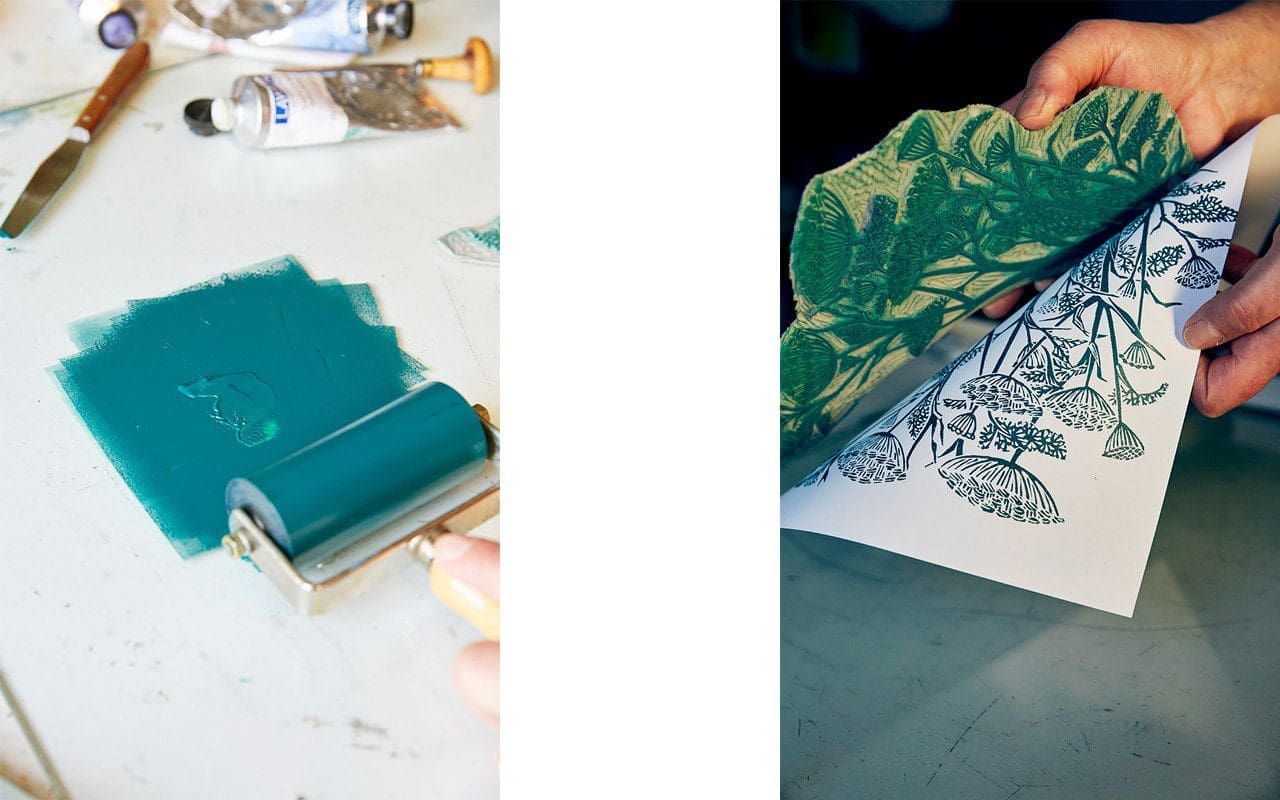

I do a rough drawing to show the client. Once that is approved, I transfer the image onto a piece of linoleum. I buy my lino from a flooring supplier by the metre. Cutting a design into a piece of lino calls for simplification and clarity. I am obliged to be selective. If in doubt, leave it out.

As it is a print, everything has to be done as a mirror image. I cut into the lino with a set of five small v-shaped and u-shaped gauges. I have to decide whether to show the veins on a leaf, or the outline of a leaf, or I can just depict the solid shape of the leaf. Less is more. The areas of lino that I cut away won’t print. When I roll the ink onto the finished block, the remaining lino will pick up the ink. Then I make a print using my big press.

I can print in black and white, but mostly my work is brightly coloured as it will be used on a book jacket or for packaging. I can add more than one colour onto each block using small rollers. Where the colours merge makes an interesting blend. Then when I print a second block over the first print, more subtle and interesting and unexpected things happen. The inks can be mixed to be quite transparent, or quite opaque. I use linseed oil-based relief printing inks from Lawrence. I was introduced to Lawrence’s at art school, when they were at Bleeding Heart Yard in London. I am still using the same tools that I bought there, though the smallest v-tool has been retired and replaced: it became rather short after years of sharpening.

Making the drawn line into a cut line transforms the quality of the line itself. I am still always surprised by what I have created when I see the first print.

How did you approach the commissions for Natural Selection ? The cover image features a house which looks very like Dan’s house in Somerset. Did you research images of it, or is it a happy accident that it looks so similar ?

I was so pleased to get this commission, I knew right away that I would love to do the book. If the house on the cover looks like Dan’s, then that is a happy accident: that’s my house more or less. Mine actually has dormer windows, but I thought Dan’s house would look more English with ordinary smallish windows.

I first came across Dan’s name in the early editions of Gardens Illustrated when it was something new and special. And have followed his career haphazardly, since I don’t have a television, in occasional gardening magazines. Dan decided to have one plant portrait for each month. We had different ideas about which plant, but I was happy to go along with his choices. The only problem was that by then it was October, so I couldn’t draw all the plants from life which would have been preferable. But mostly I had drawings that I could refer to. I happily use photos for reference, but I still think the best work is done from life if possible.

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural Selection

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural SelectionWhat are the greatest challenges in your work ? Can you tell me about the brief for the murals at Beatson Hospital in Glasgow ? How did you visualise your work for such a large piece and how did you scale up your linocuts for the site ?

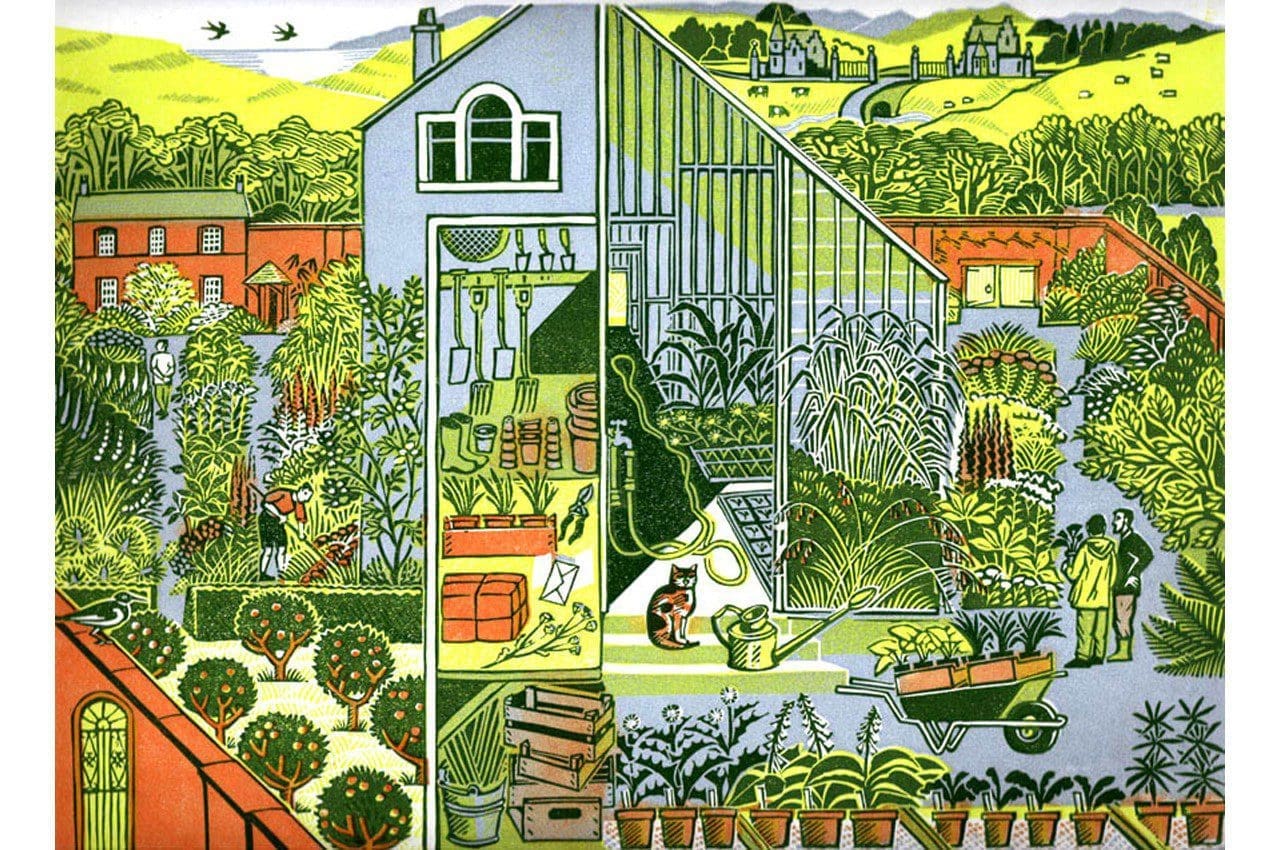

I knew my linocuts would look good reproduced at a larger size. It enhances the irregular quality of the line, the handmade look. It was exciting to see the A4 size images enlarged to two metres high, extending over four thirty metre corridors. Each corridor was named after a Scottish island as a theme, and I rearranged my selection of details of the countryside to create a harmonious and varied flow of landscape and wildlife for patients and staff to enjoy as they passed by time after time.

The Beatson is the hospital for treating cancer patients in Glasgow, and the Macmillan Fund provided money for an art consultant, Jane Kelly, to enhance the whole interior with colour and style and fittings, with the Scottish west coast as the overall theme. Very worthwhile and successful.

Each job is a challenge. The deadlines are tight. Understanding what the client has in their head is a challenge: they often know what they want, it is my job to find out what that is and turn a concept into an artwork.

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

You have produced a number of illustrations for Cally Gardens over the years. It was a shock to hear of Michael Wickenden’s recent death in Myanmar while on a plant hunting expedition. Can you tell us about your relationship with Michael and the nursery ?

Michael’s fantastic nursery is an hour’s drive along the coast from here. He had bought a derelict walled garden thirty years ago and filled it with his vast collection of plants over the years. I was there doing a drawing for the Garden History Society. On seeing the final product, Michael asked if I would do a design for him to use on his Cally Gardens mail order brochure. We became firm friends, and the brochure has been published every year with my cover design. Until this year.

It is so sad that he is no longer with us, but I firmly believe he would be delighted to have died on top of a remote mountain on a great adventure. He knew that he was taking a big risk going to these remote places, and loved the expeditions, traveling with native guides under extreme conditions. As I tidy up my flowerbeds after the winter, I can recognise each plant that came from Cally, and I am reminded of Michael each time.

He was very outspoken and didn’t mind causing offence, objecting at every opportunity to the Plant Breeders Rights nonsense. I also learned from his example that my flowerbeds should be rigorously tidy in March. His garden looked like a jungle by the end of the summer, but in March everything (well no, maybe not everything, it’s a huge area) was cut back and isolated into its own distinct space. We all hope that some gardener with vision will grasp the nettle and keep the place going.

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

What are you working on at the moment ? What would be a dream commission ?

Just now I am designing a publicity image for an exhibition for the Royal College of General Practitioners. Then I have to print up more work for my local Open Studios event 27th-29th May 2017. I also teach linocut workshops, including residential courses at Higham Hall in the Lake District three times a year which I enjoy.

A dream commission: Natural Selection in an Italian palazzo with a cook and a housekeeper and a gardener. In the sun, with a swimming pool. With a whole year to do the work, so I could draw each plant from life. My partner and children and friends, and my agent, would come to visit at intervals… Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Previous

Previous

Next

Next