Eighteen months ago Guardian Faber approached me to compile a collection of articles from the ten years I wrote for The Observer. Natural Selection, with illustrations by Clare Melinsky, is due to be published this coming May and we prelude it here with a small selection to whet the appetite.

It was a privilege to be given the opportunity to write a weekly column and to record my gardening activities and ruminations in words over so many years. The pleasure I take in writing stems partly from this ability to record my gardening life and thoughts. The pieces span the whole decade and the shift – about half way through my time there – that charts the change from gardening in Peckham to the move we made to our land here in Somerset.

That move was the biggest change I have ever made in my gardening life and one that it has been good to look over again while editing the selection. The articles follow the course of a year, and explore the gradual seasonal changes that you are aware of through the act of gardening. Subject matters are invariably rooted in their moment, but they vary from the very practical and horticultural, to more in-depth essays about things I have fallen for or that have moved me and that I want to share with readers.

Writing is something that I enjoy for the act of pinning down a thought that may be fugitive or transitory. Gardening is when the best of these thoughts happen, and so one, it seems to me, would now be almost impossible to do without the other.

Fritillaria meleagris

SNAKES IN THE GRASS

5 April, London

One of my clients lives in a sturdy stone cottage in the Yorkshire Dales. It sits on the brow of a hill, facing south, with the valley sweeping away as far as you can see to either side. There are dry-stone walls sectioning the land and on the far hills the haze of heather smudges the tops in August. You feel the weather with intensity. When I was last there the January gales made the house shudder and the valley was a pure and glistening white with frost. But now, at the beginning of spring, the most extraordinary thing happens. The midwinter green increases in intensity over a week or so until it could only be described as luminous. It is like nature turning up the contrast so that the fields appear to be pulsing green. Go down into the valley and the hedges will be thrumming with activity. Bristling new shoots on the hawthorn, Stellaria smattering the base of the hedgerows and young nettles as soft as they ever will be, at the best moment for making into soup. Cowslips will be gathering in strength in the open ground where the turf is kept short and when the tops of the first new grass are bent over on a bright breezy day, the meadows will literally shimmer with reflected light. This is all good news after a long grey winter and I plan to make the most of this glorious moment. It involves studding the shiny new meadows with sheets of bulbs, not great sweeps of colour-heavy daffodils, but with species bulbs that will scatter colour.

No meadow in early April would really be complete without the Fritillaria meleagris and in a week these snakeshead fritillaries will be at their best. Pushing up on wire-thin stalks, they are almost impossible to see until they arch their heads over in readiness to flower. And flower they do in abundance when they decide they are going to naturalise a sward. The sight of them in countless numbers is breathtaking. They like to naturalise low-lying floodplains and there are some incredible colonies in the lowlands of Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire. They used to be more common, but with ground drained for agriculture and building spreading as it is, the wild colonies are now few and far between.

Last year I visited a good example just inside the ring road that runs around Oxford. It was odd to be among them, sitting in spring sunshine with the Juncus and ragged robin indicating how wet the land lay year round and the traffic hurtling by. Their chequered pattern never fails to delight me. It really is like the patterning on a snake. Mulberry overlaying pale silvery scales in the dusky forms and green overlaying white in the rare but ever-present albinos. The flower looks like it has been made from fabric and starched into position with its high-pleated ‘shoulders’.

I have no grass at home in London so I have chosen to keep a couple of dozen bulbs in a pot so that spring doesn’t go by without me enjoying them. I am amazed that they do as well as they do because they are a plant that looks so much better in the wild and only really does well where the ground is damp. I do nothing more with them than bring them out from the holding area in the shade when they show and then allow them to feed up their foliage until it withers in early summer sunshine after they have flowered. The pots are filled with Viola labradorica so that they are not too bare for the rest of the year and they are completely neglected beyond the watering that is needed to keep the Viola alive and kicking.

Establishing Fritillaria meleagris in a garden setting is fairly straightforward as long as you remember their requirement for damp ground. This is unusual in a bulb, for most like to be on the dry side when they are dormant. Soil that floods infrequently and in winter will be fine, but really they like to draw upon water rather than lie in it for long periods so it is worth bearing that in mind. Though I have had success planting the bulbs in the autumn at two-and-a-half times their own depth, as most bulbs like to be, I have heard that they prefer to be planted deep, up to 15 cm. If you can get plants pot grown, though not the cheapest way to introduce them in numbers, it is the surest way of getting them established. As with any other bulbs grown in grass, leave them for five to six weeks after the flowers fade to seed and store goodness for the following year.

The fritillarias are a huge tribe of wonderful treasures and most hail from Turkey and the Middle East where they bake bone dry not long after the spring rains are finished. It is hard to see many of these in the wild now because grazing has stripped the colonies as has unscrupulous bulb collection, but try and see them in the alpine houses of botanic and RHS gardens. You will be bewitched. Most of these species are beyond me at this point in my gardening history. They need to be grown in frames and given just-so attention, but there are several which are less choosy. The earth-brown and green F. acmopetala and F. pyrenaica are easy. My childhood neighbour Geraldine had a wonderful clump of the latter growing for years in free draining ground through some low perennial campanulas. Then there is the exquisite F. thunbergii from China, with its grass-like foliage, twisted at the tips to haul itself up into the low scrub in which it likes to grow. This is a woodlander that the garden designer Beth Chatto grows well against the odds in Essex. Its exquisite green bells are the perfect companions to Trillium and Uvularia in her sheltered woodland garden.

In areas of the country where the dreaded lily beetle has yet to make its presence felt or where you can be prepared to pick off the first generation of beetles and grubs, I will always make room for F. persica. Tall, at about 90 cm, in the strongest selection ‘Adiyaman’, the whirl of blue-green foliage is up early in March and the grape-purple flowers follow fast behind. This is a plant that loves to bake, so think about it being with thymes and small lavenders, Origanum and the like. It will be withered and below ground by mid-summer having lived fast and furious.

The Crown Imperials are closely related but a scale up again in impact. Perhaps they were brought here along with the tulips as part of the trading that used the ancient silk routes. Hailing from Turkey through to Kashmir they must have been exotic treasure, and their provenance explains why you often see them depicted in medieval woodcuts of apothecary gardens and in the floral paintings of the old Dutch masters. The flowers, which hang from a cluster at the top of a waist-high shoot, were said to have not hung their heads when Christ passed them on his way to the crucifixion. They are forever bound to bow their heads as a result. Lift them up and in the base there will be a tear of nectar at the heel of each petal.

The bulbs, which go in as usual in the autumn, have a pungent foxy odour and there is something of that in the glossy leaf. They are happy in a hot spot and in good hearty, free- draining soil. ‘Lutea’ is a bright chrome-yellow, ‘The Premier’ a dusky orange and there are brick reds that never look better than when basking in spring sunshine. They display none of the earthy tones of their many relatives, nor the snaky subtlety of our British native, but every bit as much individuality.

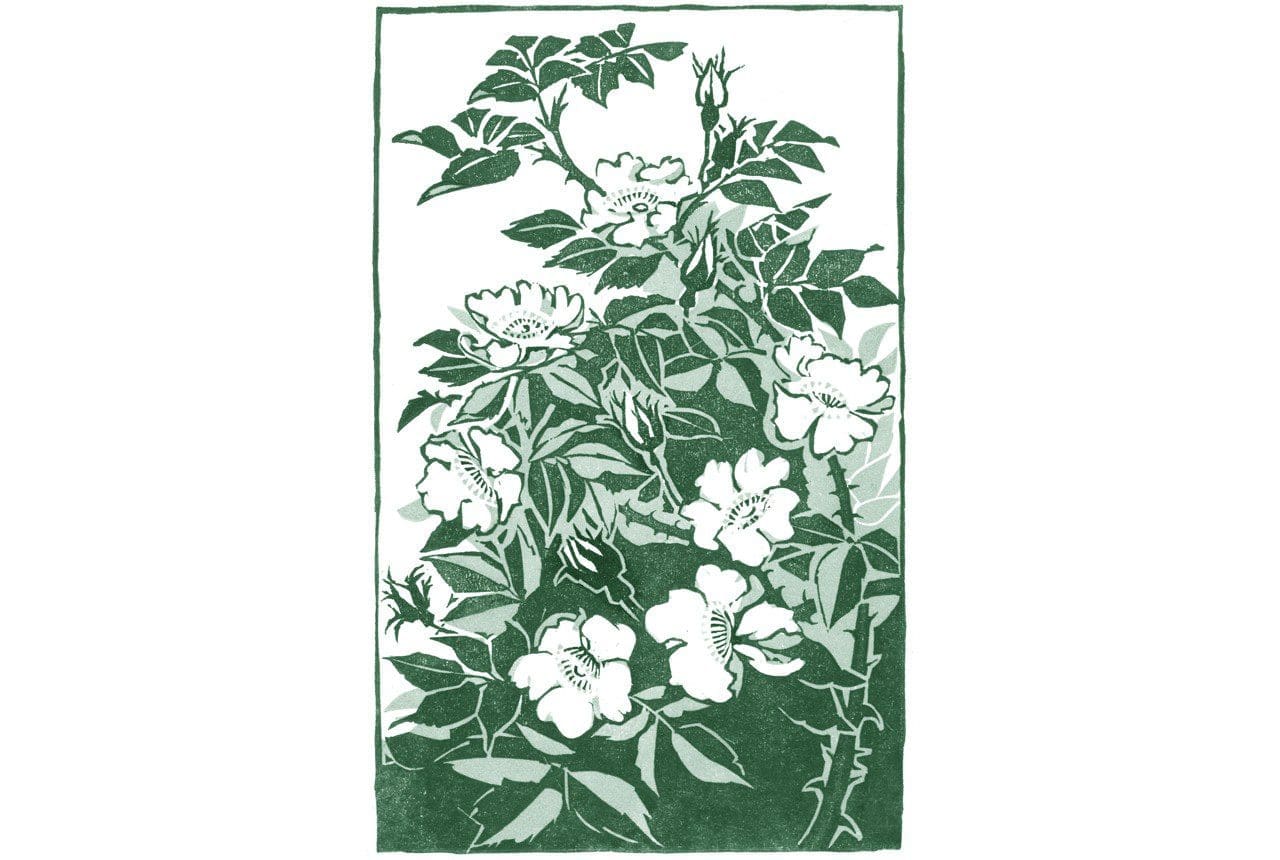

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

Rosa laevigata ‘Cooperi’

PLEASURE GARDEN

8 June, London

After finishing my studies at Kew in 1986, I spent about five years moving around: a year at Jerusalem Botanic Garden, a year a mile up a dirt track on Miriam Rothschild’s wild and woolly estate at Ashton Wold, and time out on the Norfolk Fens. I had plans with my partner at the time to buy a field on the Milford Haven estuary, where we intended to live on our houseboat and make a garden, but when my garden design business started to take off, I found myself inching back to London. I was twenty-seven and in love again, which is how I came to live on Bonnington Square, in south London.

The first time I saw the square I knew I wanted to live there. There was a party house with no floors, children running barefoot in the street, a cast of local characters who were the definition of bohemian, and the Bonnington Square Cafe, which is still run on a vegetarian co-operative basis. Friends dropped in with no notice and frequently stayed until dawn, and the boundaries between where you lived and where you spent your time were constantly blurred. One summer morning I awoke to find the outside of the house opposite had been papered from top to bottom in newspaper. Visitors often said it was like stepping back in time.

Although the Harleyford Road Community Garden on the other side of the square existed when I arrived, the greening of the square had now started. Cracks in the pavements had been dug out and planted up by the local guerrilla gardeners, and odd corners were already colonised. I had just been for the first time to New York, where I was inspired by the Operation Green Thumb community gardens on the Lower East Side. The same sense of a community working to improve its surroundings set the square apart from the roaring traffic of Vauxhall Cross, and that community has gone on to develop as one of my favourite gardens in central London.

My roof garden overlooked the site where this garden was created, on an area seven houses long that was bombed during the war. A chain-link fence surrounded the site, which had been turned into a children’s playground in the seventies, with a broken slide and dilapidated swing sitting on a pad of dog-soiled concrete. Although someone had planted a lone walnut tree, bindweed and buddleia had won the day.

In 1990 a builder asked the council for permission to store equipment on the waste ground, which alerted locals to the potential for development interest in this area of open land. Fast as lightning, Evan English, one of my neighbours, proposed that the site should be turned into a community garden. With a core group of residents behind him, he struck lucky with a local councillor who had one of the last GLC grants to give out to such a project. So, with just over £20,000 in our pockets and a team of council-appointed landscape architects, we put in the bones of the new garden.

The chain-link fence was replaced with railings, the tarmac and concrete with hoggin, and a series of raised beds created with topsoil spread over the basements of the old houses. A giant slip wheel, salvaged from the defunct local marble works, was partially reassembled to add a dramatic sculptural element. Another resident, the New Zealand garden designer James Fraser, and I put together the planting scheme and had a lot of fun mixing architectural New Zealand natives and English garden staples. A massive planting day that first autumn was followed by another party. None of this could have happened without Evan’s single-mindedness, and once the momentum was up, so was the support of the community. There was an annual street fair to raise additional funds for plants and furniture, and monthly workdays to keep the garden looking its best.

The square was given an entirely new focus with a garden at its core and created a renewed sense of pride among the residents. It was then given its official name, the Bonnington Square Pleasure Garden, partly a reference to the notorious seventeenth-century Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, partly because it had been a pleasure to create and was intended to be a pleasure to use. Life on the square had changed. The picnic lawn was busy every weekend, and we saw people who had never ventured from their houses using the park as an extension of their homes.

The following year came the Paradise Project, a plan to green the streets around the square. We were given more help with funds for trees, and soon catalpas, Judas trees, mimosa and arbutus took to the pavements – and climbers to the walls of anyone who wanted to green their building. People quickly started to plant up the pavements in front of their houses. Window boxes of herbs and flowers appeared, old telegraph poles were colonised by morning glory and vines, and a rash of roof gardens appeared, so I was no longer alone in my green eyrie.

It is more than ten years since I left the square to make a garden of my own, but the Pleasure Garden has continued to evolve with the community, which is still very much behind it. A new generation of gardeners – many of whom had never gardened before moving there – keep it feeling vital. It is an object lesson in what can be achieved when people join forces to stop so-called ‘wasteland’ being lost to yet more bricks and mortar.

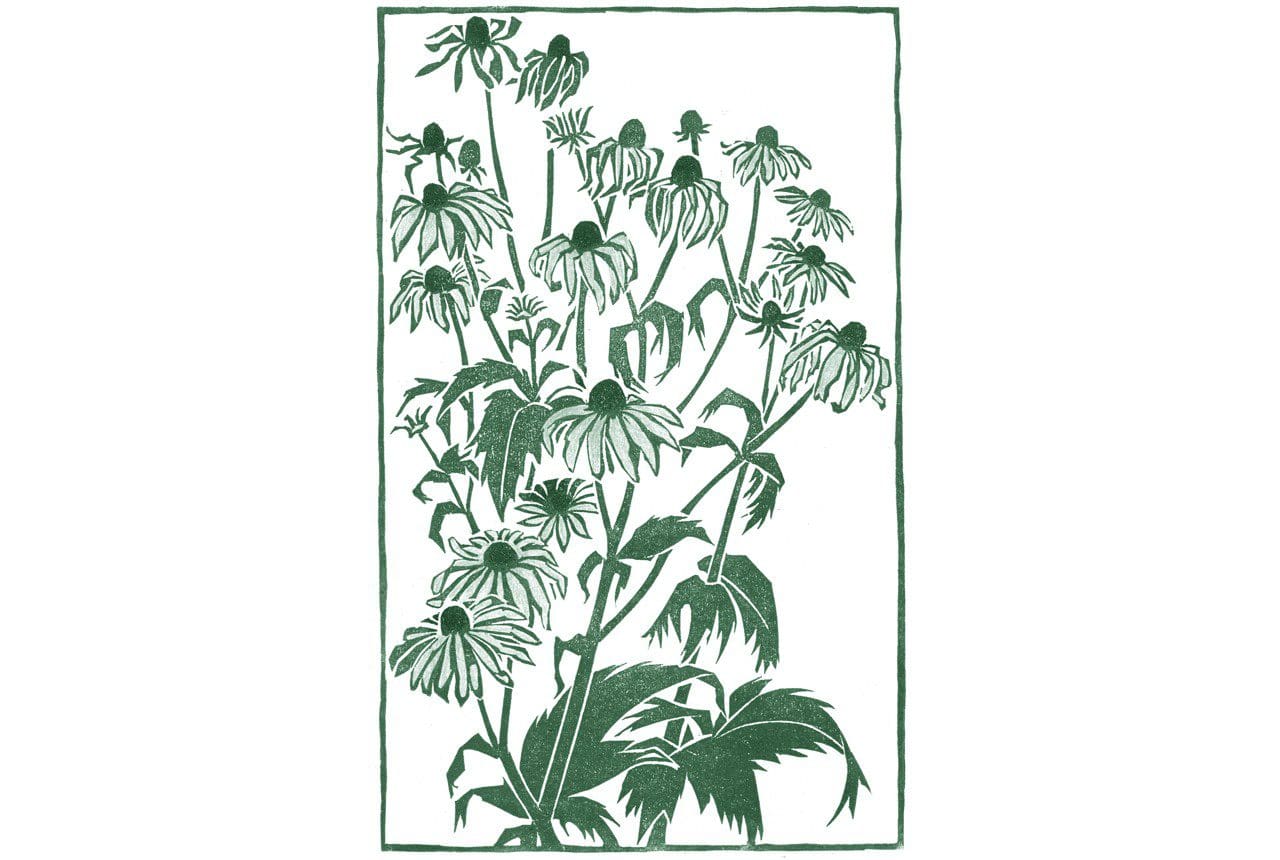

Rudbeckia laciniata

Rudbeckia laciniata

A WAY WITH THE PRAIRIES

8 December, Chicago

I have just returned from a lecture tour of the USA, where I caught the fall at its best and spent longer than ever before in Chicago, the City of Broad Shoulders. When I asked the origin of this nickname, it was proudly announced that the city believed that it should be able to carry the world through industry and innovation. After all, Chicago was home to the first skyscraper and to Frank Lloyd Wright, who developed his Prairie Style architecture in its suburbs. I had only known his wonderful, iconic Fallingwater, cantilevered over a cascade in woodland, so I was shocked to see these vast, low-slung Arts & Crafts family homes littering crisp expanses of lawn in the wealthy Oak Park area on the edge of town. Not a prairie in sight, but impressive nonetheless.

In the city centre, an industrious new wave of architecture has been revitalising the downtown area. On the way into Millennium Park, the beautiful Cloud Gate by Anish Kapoor reflects the spectacle of the city centre on its polished stainless- steel surface, capturing passers-by, skyscrapers, clouds and Frank Gehry’s Jay Pritzker Pavilion rearing up over the park like a silver dragon. Beyond the Gehry, and behind the dramatic Shoulder Hedge (to reflect the broad shoulders), lies the Lurie Garden, designed by Gustafson Guthrie Nichol, a celebrated new addition to the park. Piet Oudolf devised the planting for the garden and, among the glittering architecture, the essence of the long-lost prairie has been brought into the city.

Today, skyscrapers and concrete and lawns in the suburbs roll out from one to the next in a pristine carpet that has left no room for what gave Illinois its name as the Prairie State. The vast prairies once covered 570,000 square kilometres, from Canada to Texas, Indiana and Nebraska. In just over fifty years in Illinois alone, prairie that was seen as being rich for cultivation was swept aside to make way for industrial farming. The Lurie Garden, lovely as it is, with its tawny grasses and seeded perennials, could not have been a greater contrast to what lay around it.

Feeling inspired, and in need of some real landscape, I met up the next day with Roy Diblik, the man behind Northwind Perennial Farm, a pioneering nursery that specialises in native American plants. Roy had grown all the plants for the Lurie Garden and knew all there was to know about North American perennials. How brilliant that the garden has reactivated people’s interest in their own natives again, but how much more amazing to be taken to some of the restoration projects outside the city. Here, in relatively small pockets of land, a growing movement that started in the early sixties has seen prairies re-established by teams of volunteers. These nature lovers saw the need to act before all was lost, because today the original prairie only exists in slivers of land, rocky places that can’t be turned by the plough, and railroad embankments. Pointedly, and rather poetically, I thought, the pioneer cemeteries had also acted as an oasis for the plants that were swept away by the settlers, and it was the seed gathered in these sanctuaries that enabled the new reserves to be colonised.

I was shown one of the first restorations at the Morton Arboretum, an open area of about eight hectares. I felt so small with the grasses and eupatoriums standing at well over shoulder height, and it was ravishingly beautiful, with the only true green at that time of year being the ‘artificial’ green of the mown lawns of the gardens that lay beyond. Here there was every shade of brown, fawn and parchment white. In certain places, the hot cinnamon stems of Rudbeckia with coal-black seedheads and the grey-green of long-gone baptisia formed an undercurrent. Prairie dropseed, Sporobolus heterolepis, a grass that has a sweet, sugary perfume when flowering, formed low clearings where it had developed into a colony. Among the grasses, in a combination that it would be impossible to better in a garden, were jagged Eryngium, or rattlesnake master, and soot-black Echinacea. Silphium perfoliatum rose half as tall again as me. Its scalloped foliage had turned a leathery brown, and I stood for some time marvelling at the sculpture of it, thinking of my solitary plant in Peckham and how very far it was from its natural home.

Later in the day, Roy and I met up with Tom van der Poel, a charismatic leader in the contemporary prairie movement. He took us to Flint Creek, a six-year-old project of some twenty-five hectares. The land was purchased by Citizens for Conservation, a volunteer group which now owns 160 hectares. We plunged in after Tom as he took off along a tiny path, scattering handfuls of seed where he knew each species would have the best chance of thriving. As I followed, I asked how best to go about re-establishing an environment that had been erased well over a hundred years ago. ‘The restorations are a combination of science and art,’ he proclaimed. ‘The larger your perspective, the greater your understanding.’

He went on to explain the intricacies of the grassland as he showered seed into areas that were ‘ready’ for it; where the brome grass, the grass sown by the settlers for grazing, had been weakened enough by the other prairie plants. If they’re set free and given the room to thrive again, the process of reviving the natives is possible. Using the most vigorous species first and then inter-sowing weaker species such as the prairie dropseed and the bottle gentian, it has been possible to create microclimates to suit a wide range of plants. In just six years, 260 species have been re-established on this site alone.

Each site is sown according to the local conditions, which are often wildly removed from their original state – farmed and infertile, drained of the ground’s natural resources; but the volunteers are keen for diversity, so they ‘undo’ the sterile farmland by breaking the land drains to create a range of conditions again. The culture of burning sections to clear the thatch that builds up in time, as the Native Americans did, is still practised at the end of winter before growth starts. Tom said they only burn the prairie in sections, to allow the wildlife that has flocked back room to escape. ‘Building the food chain is just a small part of this work,’ he explained.

Every year another site is brought back in for re-colonisation by the efforts of volunteer groups such as these, and I hope that in our lifetimes this will be a chain reaction we can all be touched by.

Excerpts courtesy of Guardian Faber. Natural Selection will be published 4 May 2017, Guardian Faber, £20. Available now for preorder on Amazon.

Linocuts by Clare Melinsky

Dan is speaking about Natural Selection at the following events;

26th May Bath Festival

30th May Hay Festival

Previous

Previous

Next

Next