I first became aware of James Golden in 2009 when Huw showed me his short online review of my book Spirit: Garden Inspiration published on his blog The View from Federal Twist. From time to time Huw would direct me to James’ blog posts as he felt we had a shared perspective on gardens and I was always struck by the thoughtfulness and care in his writing, his philosophical and questioning approach to the matter of gardening and the undeniable beauty of the naturalistic plantings in his woodland garden. It was fascinating to see a garden being steered so apparently lightly and his low interventionist approach to working in his environment.

The following year James came to hear me speak about the Spirit book in New York and expressed an interest in my work on his blog, which is when Huw and I started an intermittent correspondence with him. It took a while before the stars aligned, but in 2015 James travelled to the UK and asked to visit the garden I had made at The Old Rectory in the Cotswolds. We made the arrangements, and I was very much looking forward to meeting him there, but then I was called away to Japan. James’ online account of his Old Rectory visit and his views of the Chelsea Flower Show garden I designed for Chatsworth and Laurent Perrier appeared shortly afterwards. It was clear he was a kindred spirit.

And then, last year, after we had finally published Tokachi Millennium Forest, Huw asked our publisher, Anna Mumford, what she was working on next. “Do you know James Golden?” she asked. “He’s writing a book about his garden at Federal Twist.” Huw told Anna about our tentative friendship and admiration of the spirit of his garden and suggested that I would be happy to support the publication of the book in any way I could. And so, last Sunday, James visited Hillside. It was a beautiful, mild autumnal day. The garden was at its pre-collapse peak and we walked the fields and gardens for several hours.

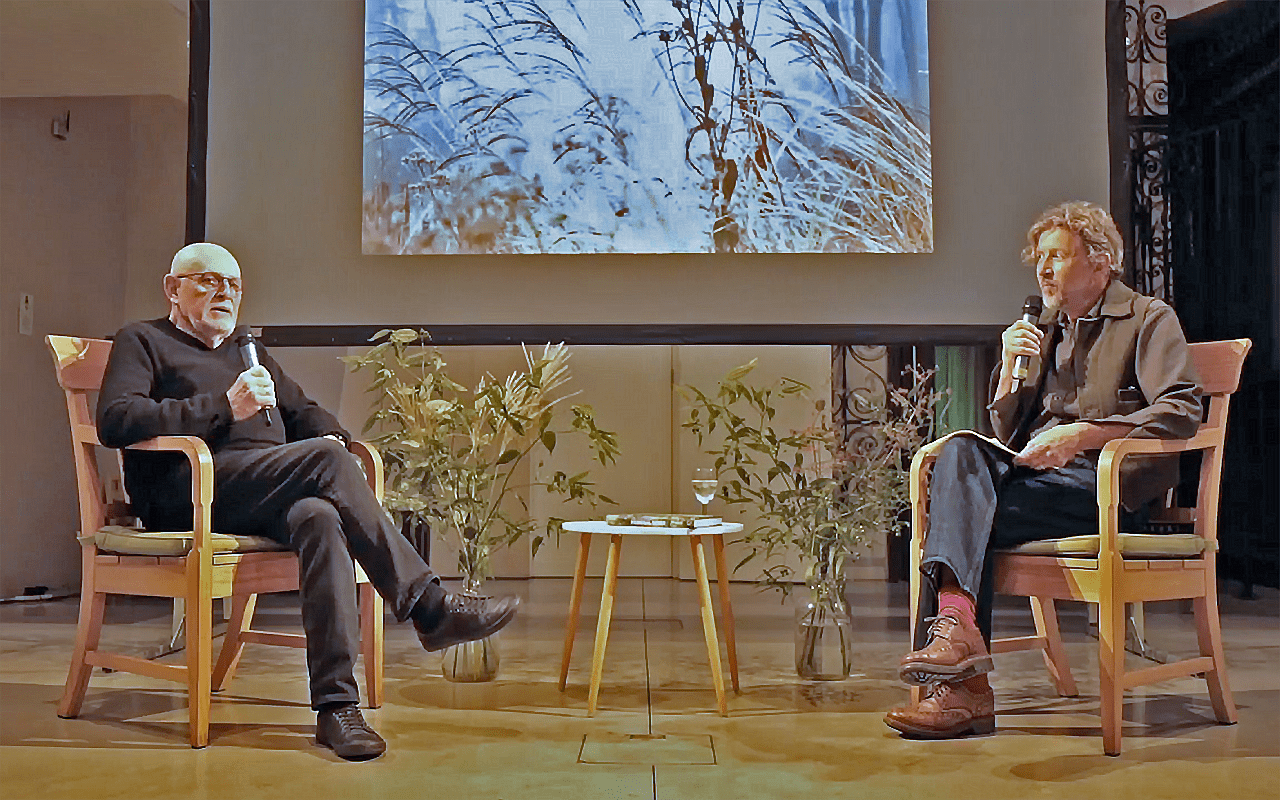

Then, on Tuesday evening, we sat together at The Garden Museum and had a conversation about the how, why and wherefore of his garden.

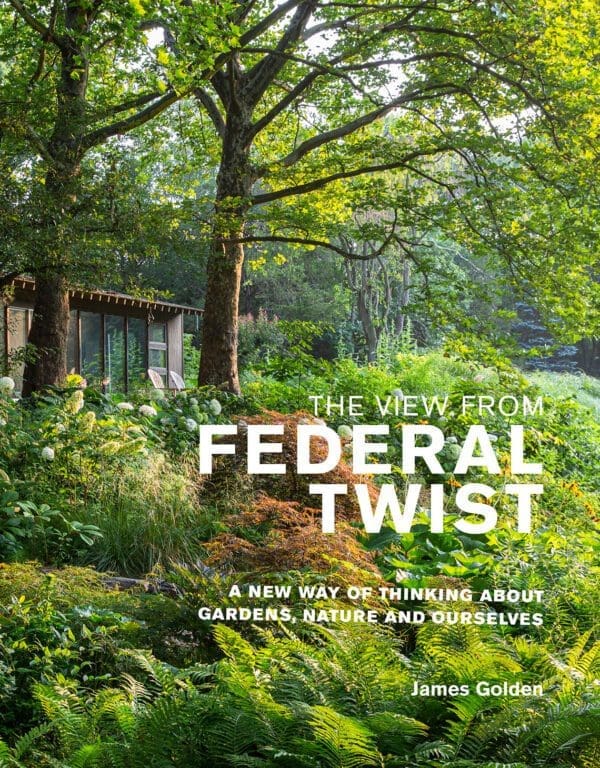

Below is a transcript of the beginning of that conversation, followed by an extract from James’ book, The View from Federal Twist: A New Way of Thinking about Gardens, Nature and Ourselves.

Dan: James, I wanted to open the conversation about this evocative place with you talking to us about your journey. How did you get to the point of being drawn to the clearing in the woods?

James: I usually say that I’m a latecomer to gardening, because I made my first substantial garden late in life. I grew up in the American south, in Mississippi, and almost unconsciously I fell in love with plants. I remember driving out of our small town over a wetland with my family and there’s this shrub blooming in the wetlands covered in white, flossy flowers and I asked my father what its name was and he didn’t know. That was the usual response I got when I asked about a plant. He knew how to grow potatoes and tomatoes, but he didn’t know this plant, which I learned probably fifteen years ago was called Baccharis halimifolia. At my grandmother’s house I saw an American beauty bush (Callicarpa americana), which has beautiful purple fruit, very notable in the landscape. Nobody knew what it was. I admired these things, but I never felt the urge to garden or to do anything with them.

I remember Cercis canadensis blooming in the spring. We call it redbud. You know, I think Cercis siliquastrum, which is a relative. It blooms in small purple, almost like buttons, just groups of little buds emerging from the dark bark. A beautiful, beautiful tree. But I think I felt, perhaps, that I was a boy so I shouldn’t appreciate things for their beauty. I’m not sure. Much later in life, actually after moving to New York, and my partner, now husband and I bought a house, a brownstone in Brooklyn and I started a small vest pocket garden. Only fifteen years ago we got a place in New Jersey and I started the gardening with a real passion and it became a really meaningful part of my life.

Dan: James, you say in the book that you entered the realm of garden making through reading.

James: I did. The first book on plants I read I think was The Well-Tempered Garden by Christopher Lloyd, which didn’t have a terrific meaning to me, being from America many of the plants weren’t known to me. Later I stumbled on a group of books that were coming out as Piet Oudolf was becoming more and more popular. Many of the books were by Noel Kingsbury and Piet Oudolf or by Henk Gerritsen and Piet Oudolf. They were large books with beautiful photographs and I fell in love with that kind of gardening. Subsequently I have read all of Dan’s books and learned gardening from books, not from actually gardening. I have done gardening and I do gardening, but I don’t particularly care for the labour of gardening.

Dan: I think through reading the book one of things that’s rather wonderful about the journey of the book is your obvious ability to observe very closely. It feels like you’ve really found your way into that place through that close observation and thinking time. Could you tell us what Federal Twist was like when you first found it and what drew you to decide that was the right place to be?

James: Federal Twist is in an area of several thousand acres of preserved forest on a ridge above the Delaware River. It’s still quite a wild-feeling place. We were looking for a new house. I also wanted to make a garden, but we found this mid-century house built in 1965, with many floor to ceiling glass windows, views out in all directions, and we fell in love with the house. It was described as vaguely Frank Lloyd Wright-like. It’s not Frank Lloyd Wright at all, but there are similarities it even had a few Japanese influences. I know the architect went through several designs in designing the house and at one point he had an entrance with a shoji screen, so he was thinking Asian and Japanese when he designed it.

We fell in love with the house and outside was an absolute ugly, derelict woodland. There was no open space. The soil was very moist. It was heavy clay. Behind the house was a monoculture of junipers, but we fell in love with the house. I had my doubts, but I had this stubborn feeling that I was going to make a garden here. I would find in books how to do it.

Dan: I was really taken by your relationship with the garden and felt that there were these wonderful parallels between how I feel about my place too. One of the things that I found really moving – there are two pieces that I’m pulling together, they appear at slightly different places early in the book – you say, ‘Federal Twist exists only because I create it from day to day. When I die it will cease to exist. We are one.’ And then you say, ‘I wanted to live in a garden, live a garden, in fact, to be a garden.’ And I think those are amazingly resonant things to read in a book. I wonder if you can talk to us a little more about that synergy.

James: Well, one aspect of gardening in the woods is that the woods is constantly trying to re-take the garden. This is so in America, especially, where there are so many woods. So there’s that constant give and take of the wood trying to move in. Trees pop up in the middle of the garden and you have to decide what to do about them. I was also very conscious that I was starting a garden quite late in life, so I was conscious of what my future might be. How many years I might have to work on this garden and what would happen to it when my life comes to an end. Not in an overly melancholic way. Having this garden is a very joyful thing, but I do think of where it belongs, ultimately, in the universe and I think it has to end when I end. Though I don’t do all the physical gardening, I am the person who knows how to take care of it and I don’t think anyone else could do that. Certainly, they could do that, but it would be a different garden.

Dan: I remember someone saying to me once, ‘The garden is the gardener.’ And I think there is so much truth in that.

James: I love that.

Dan: I wanted you to talk to me about the idea of prospect and refuge and the house in the clearing and the woods beyond. How does that play into how this place feels?

James: Well, when we bought the house there was no space, there was no clearing in the woods, so we removed seventy or eighty trees and created a clearing in the woods. It’s an archetypical American landscape type, because it goes back to the beginnings of our history and a land where white people moved in and probably really didn’t belong. They had to build houses with open spaces around them so they could see danger at a distance. The clearing in the woods, that concept, carries with it all of those, some of those emotions from the past, the idea of danger, of threat. Being in our house in the middle of the night or being in the garden in the night can be frightening.

Dan: I remember being a child growing up in a wood and I used to run along the lane at this time of year from the school bus and the exhilaration I felt as well, so it wasn’t entirely bad.

James: No, and then in the daytime it is entirely different, because most of the light comes from this oculus above created by the tops of the trees around the clearing, but in the morning and in the late afternoon the sunlight will break through the trees even when they are heavy with leaves and spotlight individual parts of the garden, which creates very bright spots and next to them very dark spots, so you can see this kind of beautiful chiaroscuro developing. It’s very transient, changes in light like that. That is one of the beautiful aspects of the clearing in this place.

Dan: You punched that hole in to see the sky, didn’t you? So you removed those trees to make that light pour in.

James: Yes, and the light’s important, because in this constricted space you’re conscious of the movement of the sun, and with the tall trees the shadows, hour by hour, change direction and change angle. Also, the sky opens up a vision of all kinds of weather. Beautiful cloud formations, snow. I have some wonderful photographs of cloud formations in the sky. It becomes sort of an observatory.

Dan: Beautiful. You say here – I’m just going to quote you again, as your writing’s so good – ‘I designed the garden to encourage exploration and attention to detail – to put you in a relationship with the garden. The experience is like giving over control, being open to feeling the garden push back a bit, and allowing the garden to take charge.’ If you could just tell us a little bit about that.

James: I actually came to experience this when I started opening the garden to other people. Though the garden is only one and a half acres in size, on a day when the American Garden Conservancy people come there might be over a hundred people visiting and quite a few of them would come to me and tell me they were lost and I thought, ‘How silly. It’s only an acre and a half.’ But in fact I garden on wet clay, I grow highly competitive plants which get very large – by midsummer much of the vegetation is above head height – so when you’re walking on a path you don’t see other paths and it is quite easy to get lost and become disoriented. I don’t, because I’m used to the space.

There are parts of the garden – I call it a prairie garden – prairies are naturally planted very thickly, so there are parts of the garden you can’t enter. The only way to move through the garden is along pathways that circulate through the planted areas and as you get lost or start wandering you do begin to feel that maybe there are places where you don’t belong, that maybe the garden is pushing back a little bit. The thought is that the garden is reminding you that many things are going on in it. Insects are reproducing, insects are pollinating, gathering pollen, bees are gathering pollen, the frogs are doing whatever they do. There are all sorts of life forms and processes going on in the garden and when you enter the garden you are not the centre of the garden suddenly. You are simply one of many different processes going on in the garden. I think having that perspective is a very important one in the world today.

A film of the talk will be available to watch on The Garden Museum website from next week.

Federal Twist is a landscape garden, not a traditional garden. It has no lawns, no flower beds, as such, only a naturally shaped landscape, a surface layered by perennials, grasses, shrubs, and a few understory trees. You move about on a series of paths that, all told, are far longer than you might expect in a relatively small garden. You are immersed in vegetation. Along the way are stone walls, reflecting pools, several small areas for lingering, and a small pond teeming with dragonflies, frogs, and other aquatic life. The purpose of the garden is reflection and pleasure—the simple pleasure of sitting out on the terrace overlooking the garden, feeling the inconstant breeze, listening to sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) leaves rustling above, to birdsong in the forest and to frogs croaking and splashing in the water below; exploring the pathways, many hidden by the abundant growth of midsummer, catching the light and shadow as they cross the land, glimpsing moments of intimacy—and for experiencing the marvels of memory, nostalgia, and feeling. The garden has no utilitarian purpose whatsoever, unless you allow for a human utility, a place to experience the atmosphere and the mood of the day, to think, to talk, to muse, to remember, to be.

Why do I call Federal Twist a landscape garden, not just a naturalistic garden? It violates many expectations of a landscape garden, certainly those of the 18th-century English landscape garden with its broad sweep of Picturesque landforms, water, forest, sky, classical follies and ruins so prominent in the paintings of artists, such as Claude Lorraine, who were the impetus for that style. I twist the concept a bit—quite a bit. One main reason is evident if you look at the image (below) of the sun rising behind the wall of trees on the far side of the garden, opposite the house, or the second image showing the long view of the garden with immense trees in the distance. These images make it dramatically clear that important elements of the garden are ‘capabilities’ of the landscape, not part of the garden at all. I didn’t make them; I simply recognized them and their value.

Back at the beginning, when I started the garden, I already recognized the landscape had a characterful identity and atmosphere. Any garden I might make would have to work with that landscape. Making the landscape part of the garden and the garden part of the landscape was my aim from the start. I wanted to anchor the garden in the landscape so there would be no visible boundary between one and the other. I wanted the garden and landscape to feel they were one. To do this required exaggerating views, manipulating scale, using simple, appropriate materials such as the local stone, amplifying it a bit by making it into walls and simple structures, adding an abundance of paths, using plants with a wildish quality, keeping dead tree snags—all toward the end of making the landscape garden appear effortless and at ease with itself.

Balancing the idea of the visual ‘landscape garden’ was my decision to make Federal Twist park-like. It is a garden of paths, and has as its primary purpose walking and exploring the landscape. Though you can stop and see the details, the focus is on the idea of landscape—the clearing in the woods, an American landscape, but one that faintly recalls its precedents in another time, across an ocean. If it were possible, I’d have the garden open for anyone to visit at any time, just as you might a public park.

Although Federal Twist is in a historical lineage that descends from other garden traditions, it makes no pretense to be what it isn’t. It is a distinctively American landscape type—a clearing in the woods—rather common here because of our extensive woodlands and history of living in them. America does not have the centuries of cultural history found in Europe and many other parts of the world—nothing like the layers of history you find in the UK, for example, where structures and artefacts perhaps several thousand years old may be uncovered in a field of cabbages. In contrast, Federal Twist feels rather recent, even transient—as if it might just disappear, be absorbed back into the woods.

It is an American landscape garden, but I do not mean it is representative of American gardens; it has no lawn, it is ‘untidy’, it is rough, and its boundaries are not obvious at all because they blend with the surrounding woods. It is the antithesis of most gardens and yards of suburbia where utility reigns, where foundation plantings closely hug houses and the use of trees and perennial plantings is stinted so they will not be impediments to mowing, where there is little room left for imagination, inspiration, contemplation.

Its design also is influenced by the idea of wilderness, of the forest and forest life, of the vast Midwestern prairies and meadow-like settings in the East, and by the strivings of some aspects of the American psyche, such as the vague desire to escape urban life for the country. Federal Twist resonates with the voices of such early American idealists as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, leaders of the Transcendentalist movement in the period of early intellectual awakening on this continent, in a time when forest was a far more pervasive landscape than today. In Nature, Emerson wrote:

In the woods, we return to reason and faith . . . Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

These words are classic in the American literary canon (and surprisingly reflect both German Romanticism and Asian religious precepts), but from the perspective of today, they sound distant and faint, even quaint.

Can a garden still be redemptive, transformative? Can it bring place and meaning together? It is very difficult even to raise those questions in the American culture of today.

Transcript of James Golden & Dan Pearson’s talk and photograph of them both courtesy The Garden Museum.

Extract from The View from Federal Twist: A New Way of Thinking about Gardens, Nature and Ourselves and James Golden’s photographs courtesy Filbert Press.

Published 6th November 2021

Previous

Previous

Next

Next