ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

The garden is cleared now of last year’s growth and what has stood the winter. It is a process that runs over a month of weekends and witnesses the last grips of winter and the first of new life. The meaty red nosing of peonies, almost as good in shoot and anticipation as later in flower. Newness appearing around them daily. Lime green shoots on the hemerocallis, the visible inching of regrowth where the pennisetum were cut hard back just a week ago. It is a garden gathering pace and we need to keep moving now to ready it with final edits before mulching. The last big gesture and the equivalent of smoothing a quilt.

It is four years, almost to the day, since the first section was planted. The second half followed the autumn of that year and the two halves are all but indistinguishable now that they have grown in. Already we have made the first big splits, our hearty ground rearing unexpected bulking in some of the perennials. Sanguisorba that required a crowbar to lever them from their grip. One Amazonian hellebore, apparently with extra genes, did so well in every department it just looked out of place. After overwhelming its companions for four springs in as row, I finally went to battle last week and lifted it. The struggle took time and eventually I heaved it out with a huge rootball that had to be rolled into the wheelbarrow, for it was too heavy to lift. I put it, carefully bundled with a label saying ‘Please help yourself.’, out on the lane. Though it was a Sunday afternoon it had gone within the hour.

These changes make the difference. With half the sanguisorba split randomly, they will feel like a family with differing generations rather than a pack of heavies. And so the garden retains a feeling of having evolved here, with the weights of the plants in balance and differing much as they do in the meadows. Mother plants and their offspring.

An evolving garden becomes more interesting for the weave that inevitably happens when you begin to see the self-seeding and my final edit before the mulch goes down is to manage this migration. Digitalis ferruginea that would rather be on the edges and not in the shadows of the middle of the beds. Their tall poker-black seed heads cast a million and one seedlings, not too far, but far enough to jump the path. The seedlings that fall into the crowns of anything that is slower off the mark, like panicum, will be winkled out. Those that fall into a gap where I can imagine their spires ascending will be left for the feeling of having arrived by themselves. Nothing makes a garden feel more lived in than an opportunist.

Not all the interlopers are welcome and the mulching will smother the majority of the seedlings. Where I feel we might need their presence – or that of black opium poppy or florist’s dill – we do “intelligent mulching”, a practice that Great Dixter’s Fergus Garrett told me about, where you spread the mulch more lightly or not at all where you want the seedlings and deep enough to smother where you don’t. The method works with self-seeding annuals like red orach and Californian poppies and short-lived perennials like Cenolophium denudatum. The beautiful creamy umbels are a good leveller in a planting, sitting easily amongst other perennials and, like the digitalis, feeling most comfortable where they have arrived by themselves.

Some of the interlopers, such as the Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’, are wilfully oblivious, setting seed after you have mulched and finding a crevice to set up a little tuber that goes completely un-noticed until suddenly there they are. I have had this plant since I was a teenager. It probably came from Great Dixter originally as it was selected by the great Christopher Lloyd himself, found in the surrounding woodland, and named appropriately. I do not mind it moving about and I have no idea how it moves so far, the seedlings sometimes springing up in another part of the garden entirely. Leaves as dark and iridescent as beetles’ wings and flowers as gold and uplifting as the very season they make their own. Let them move about as a ‘Brazen Hussy’ might, for they are gone and have not imposed themselves by the time the growth closes over around them.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 March 2021

The Tenby daffodils are flaring on the banks that fall steeply into the ditch. Backlit by morning sun they are the purest of yellows, brilliant and bright and so very full of life. The tilted buds are already visible breaking their sheaths as the snowdrops dim and the primroses take over and begin their moment. The narcissus join them then, not to overshadow as you might think, but in a partnership of yellows, the colour of spring and new life.

Now considered a subspecies of our native daffodil, N. pseudonarcissus subsp. obvallaris is found locally near Tenby in Dyfed, South Wales, where they have a small range of natural distribution. Their cousin, N. pseudonarcissus, is variable, with a soft yellow trumpet and palest yellow petals, so a group registers quite differently and they have a softness that sits easily. Not so the Tenby daffodil which is brazen and to the point, being bright chrome yellow throughout. Though this might not be easy in a larger daffodil, the Tenby is no more than a foot tall and everything is perfectly proportioned and neat. Thus they weather the March storms and stand like a person with innate confidence that is happy in their own skin.

The crease in the land that we call the Ditch is far more than that. It is the divide between the ground that we garden and the rounded rise of the Tump that we look out upon and forms our backdrop to the east. The spring-fed rivulet that runs quickly down it is constant and gurgling, even in summer. The silvery slip of water was revealed when we cleared the brambles 10 years ago and fenced it on both sides so that this distinct habitat could become an environment of its own. We have been building upon the nature of this place ever since. Splitting the primroses that sit happy in the heavy, wet ground and stepping plants through it that are either closely related to the wild plants that thrive there or feel right and can cope with the competition.

The Ditch is a place that we garden lightly and the plan is to one day have it naturalised with bulbs that like the conditions here. Snowdrops and aconites to start the year and snakeshead fritillaries and camassia to follow. The Narcissus obvallaris are grouped loosely around a staggering of Cornus mas, which start to bloom when you can feel the winter easing.

So far the Tenbys have not started to seed, but I hope that our man-made imprint can be softened with seedlings that find where they want to be. This has begun already with the straight Narcissus pseudonarcissus, which I’ve been planting lower down the slopes and, in an echo of the ones we found higher up the valley, growing on little tumps that run alongside the stream where the hazel grows. They sit there with the young Dog’s Mercury as a marker of this ancient woodland and looking down on all they survey. The way they grow in the wild is a good measure for where they want to be when you find them their home. Cool, but not in the wet hollows and with a little shadow later to ease up the competition of the more thuggish grasses.

Having been stung a couple of times with narcissus orders that were incorrectly supplied, I started three years ago by potting up a hundred bulbs, two to a pot, as I needed to know that we were putting the real thing into this wild place. It was the year that Huw’s mother passed away and, as his family are from Swansea, it felt fitting to be planting them out just a fortnight after she died. The Tenbys start to bloom around St. David’s Day and, when the first yellow shows, we add another round of plants potted up the previous autumn. Midori and Shintaro from Tokachi Millennium Forest took part one year when they were here to stay on a ‘gardening holiday’ from snowbound Hokkaido, and it has now become something of a tradition to plant a number round about now to find the places in the ditch where we feel the light needs capturing.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 March 2021

I first encountered Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’ around twenty years ago at Stoneacre in Kent. At the time our recently made friends Richard Nott and Graham Fraser were the National Trust’s tenants and, as its custodians, they had woven a thoughtful new layer into the garden that played to their interest in colour. They had recently exchanged their lives running Workers For Freedom, their successful fashion label, for a new life in the country. Richard was studying painting and Graham, the history of both the garden and the house, which was restored in the 1920’s by Aymer Vallance, the Arts & Crafts architect and biographer of William Morris.

Together they took to the garden, moving easily from one creative discipline to the next, enjoying the fact that the worlds were easily interchangeable. It was precious time that we spent there and, with weekends away from our south London lives, in the idyllic setting of this place it felt like there was time to talk. We workshopped the planting and in the easy world of this garden the conversations moved effortlessly back and forth to cover all manner of territories. With life experience that we were yet to have, our new friends provided good council and helped build confidence about doing what was right for us and being sure of our direction.

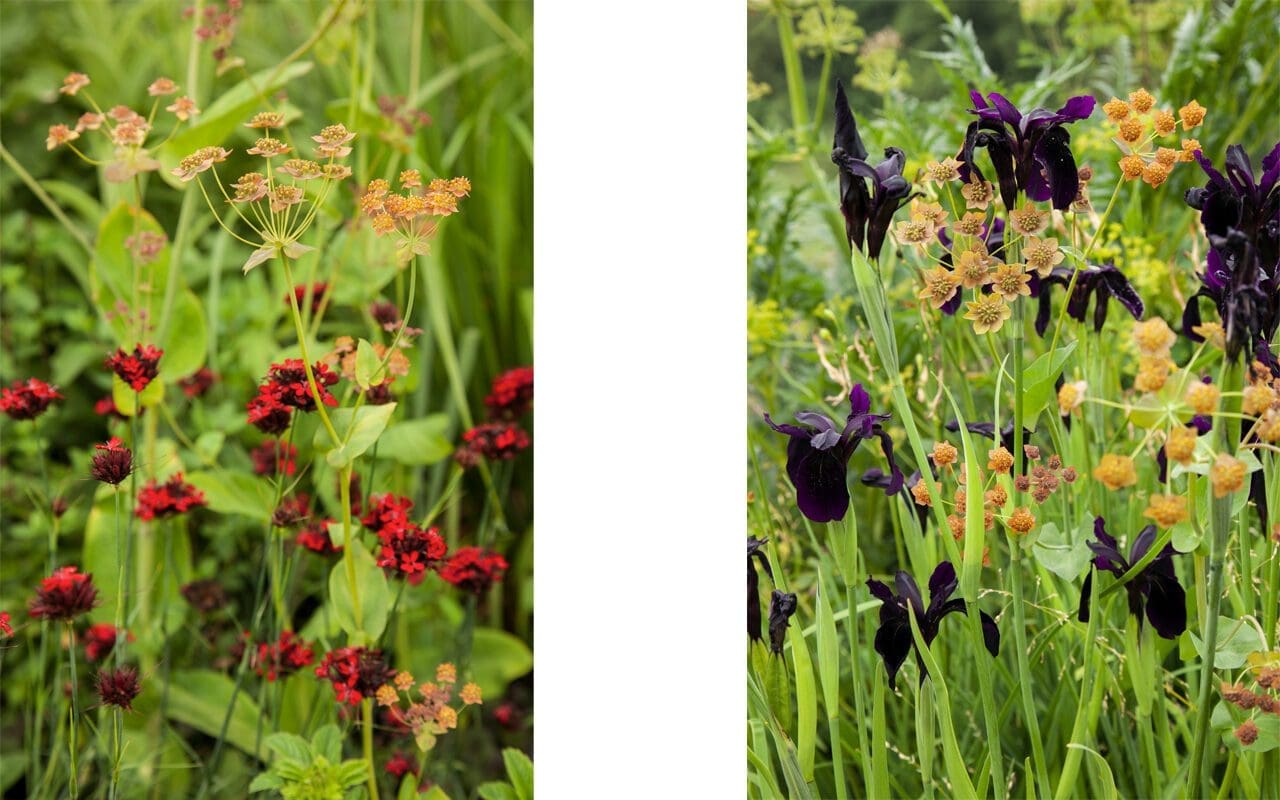

Stoneacre is a garden of rooms that give way one from the other as you walk around the half-timbered hall house. A straight stone path sloped gently to the front door and they had dug up the lawn to either side and planted a pair of gauzy, golden borders that rose in early June to shoulder height with the shimmer of giant oat grass (Stipa gigantea). As you walked the path the detail in the planting revealed itself. Hemerocallis ‘Corky’, a delicate daylily with a dark reverse to the petal, provided the base note of gold. There was saffron Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora ‘George Davison’ and later Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’, but there was a secret ingredient that provided the planting with a burnish. The bupleurum hovered amongst it all as a mutable undercurrent, a presence that was hard to detect at first until you had tuned your eye, but once you had it, it was the thing that drew you in and held you.

A clutch of seedlings found their way back to the garden in Peckham where they seeded about obligingly. Never moving further than the cast from a bent stem in high summer, but finding their niche wherever they like the territory, the tiny seedlings are easily distinguished in spring. Brilliant lime green cotyledons, two narrow slashes, appear early in the season. They arrive in a rash where they find open ground and soon form a bright first leaf the shape of a paddle. Where there is light and not too much competition they spend their first year hunkering to form a neat rosette. In the second year they throw the first flowering growth, sending up slender stems in early summer with a dusty bloom that softens their presence. By the middle of May the first umbels are filled out and standing tall and free of foliage. Finely spoked they throw just enough florets skywards, each with a neatly cut ruff and an inner button of stamens.

The shifting colour of ‘Bronze Beauty’, the form most commonly available, is hard to pin down ranging as it does from cinnamon to ochre to tan, but it compliments everything. I have not found a companion I do not like it with. I will determine a combination that I think will work well, but its easy nature will throw it into new territory together with something you simply hadn’t or wouldn’t have thought of. I am very particular about colour, but I rarely find it appearing anywhere that I find it jarring or out of place.

Advice if you are reading up about Bupleurum longifolium is to plant it in an open, sunny position. Yes, the low rosette enjoys light and suffers if it is overhung by neighbours, but we have found here, where we have all day sunshine, that it prefers to set seedlings on the shady side of the bed and those in full glare do less well. I think ‘open meadow’ when I plant it, so that it can rise up in company, but not so much that it feels overcrowded.

Although it is now finding its own way in the garden and is never competitive like its acid-yellow cousin, Bupleurum falcatum, which we also grow, the plants last three to five years and then hand over to the next generation. I always have a pot full of seedlings in the frame for good measure. They make easy additions where you might suddenly find yourself with a gap come spring. Always sow fresh, as all umbellifers (Apiaceae) do not last if kept and overwinter with a little protection. It was one of these pots of seedlings that found their way back to Richard and Graham a few years ago when they left Stoneacre to make their own garden at a new home on the south coast. An easy gift to return for such a treasured introduction.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 June 2020

The opium poppies have been growing into the lengthening evenings, to race skyward and seize this early window of first summer. They come from nowhere it seems and typify the current feeling of the garden burgeoning.

Their seedlings are already visible in March and one of the first to germinate into open ground. Blue-green and easily distinguished, they take the disturbed places where there will be a gap to ascend into the very moment the weather warms. Being winter hardy and germinating the moment the season turns with the promise of spring, they have the advantage, hunkering down and establishing good roots and core strength. In truth there are several rounds of germination as seed is brought to the surface whilst cultivating, weeding or clearing the winter garden to expose fresh ground, but the first are the strongest, bulking up in April and muscling out anything nearby that might show a glimmer of tardiness. Their precocious behaviour extends to their siblings and you will need to thin a colony if you are after plants that are muscular and soaring.

I grow a black opium poppy here and it is my one and only. A single form and a chance find that I made when cycling to work once in my early twenties. They were standing tall alongside a black wooden bungalow in Hampshire. Black on black, fluttering against the stained shiplap. If I hadn’t been looking in the way that you do when you are under your own steam, I would have missed them completely. It was immediately clear, even at distance, that they were special so I plucked up the courage and knocked at the door to ask for seed. The owner, seeing I was smitten, took my name and address and later that summer an envelope arrived with the beginnings of a now very long association. It is one that I have nurtured annually, seeding a few every year in a new place for good measure and gifting to friends and clients that I know will keep the strain pure.

Although there are other named forms of dark opium poppy, several double blacks and the deep plum ‘Lauren’s Grape’ for instance, I’ve not seen another that is quite as dark and inky throughout. To maintain the strain, I have been territorial. I have never introduced another coloured opium poppy into a garden where I have been cultivating them and any that show the remotest sign of reverting are pulled before they can pollinate a dark one nearby. I look nervously on to neighbours up the lane who have them growing freely in their garden in every shade of mauve and pink, but breathe easy that, in the ten years we’ve been here, the bees that busy themselves there must be on another flight path.

After moving them here from Peckham, I cast the seed down into the freshly turned ground of our virgin plot. Broadcast in February, the plants were up in flower by June and providing me with a new and plentiful seedbank by the middle of July. Those seeds have now found their way into the compost heap where they are content to sit dormant until they are exposed again to light and potentially new places to conquer. We had a good colony in the asparagus bed a couple of years ago, amongst the roses and throughout the kitchen garden and I am now finding seedlings in the paths that must have been dropped whilst we were clearing the garden.

The chance happening of the pioneer seedling is always heartening and we leave a few in a new place every year for the delight in the new. The first seedling to flower this year has been living with us closely alongside our covered terrace. I saw the seedling had found a home in the late winter and wondered if it would be one that would survive our lines of desire into the garden. It has, soon growing big enough to negotiate and with the promise of this very moment that is seeing it suddenly present. A filling out of blue-green buds and then, one day, a tilt in the neck of the bud to indicate readiness.

The mornings bring the flowers, crumpled at first and then expanding like dragonfly wings do when they hatch. Dark satin petals cup pale stamens and bees soon find them, noisily working in laps, the enclosure of petals amplifying the sound of their frenzy. The flowers last two to three days at most, but there are enough to run a glorious fortnight whilst the balance shifts from buds to seedpods pods fattening and tilting skyward to show you that they have nearly reached their goal. When the leaves suddenly wither and the life force of the plant is gone you see that the pepper-pot seedpods are ripe and beginning to rupture. We leave a few standing for the joy of continuity, the mission accomplished, and scatter the rest for the pleasure of helping them extend their territory.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 May 2020

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage