One of the cold frames

One of the cold frames

Auriculas

Auriculas

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018 Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

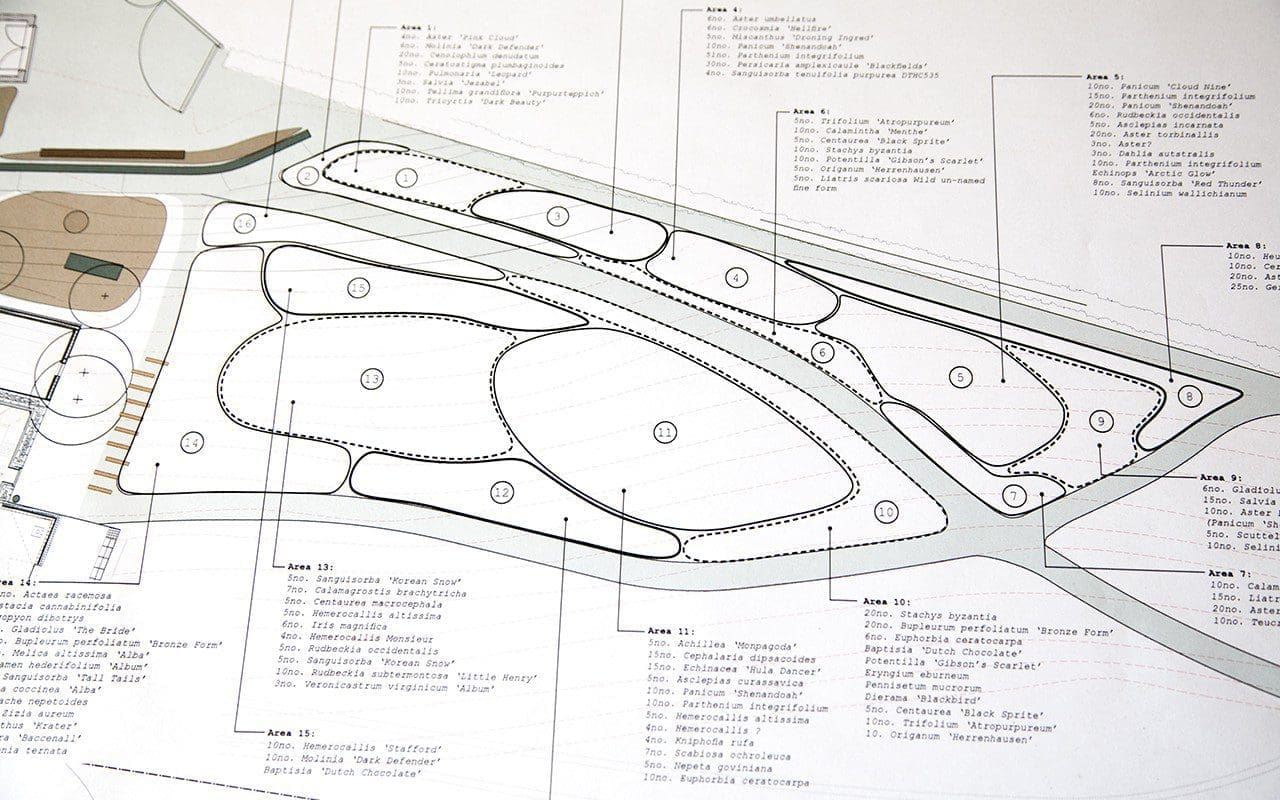

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

The self-sown sunflowers from the previous incarnation of the garden were the reminder that, just a year ago, we were growing the last of the vegetables here. I had allowed them the territory in the knowledge that this would be the end of their era, for they were in the bed that I now need back to complete the planting of the garden.

Felling them before they were finished was a relief, for suddenly, once they were gone, there was breathing space and the room to imagine the new planting. I’d also left the aster trial bed until the very last minute, eking out the weeks and then the days of its final fling. On the bright October day before we were due to lift, the bed was alive with honeybees, making the final selection of those that were to be kept for the garden that much more difficult. It was time to liberate the last of the stock beds, though, and to prepare the ground they occupied for a new planting.

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Planning what to keep and what to part with is difficult until the moment you make the first move. Over the last three years we have been keeping a close eye on the asters that will make it into the new planting. Keeping the best is the only option, for we do not have the space elsewhere and the overall composition is dependent upon every choice being right for the mood and the feeling that we are trying to create here. So gone are the Symphyotrichum ‘Little Carlow’ which, although a brilliant performer, needing no staking and being reliable and clump-forming, are altogether too dominant in volume and colour. Aster novae-angliae ‘Violetta’ is gone too. Despite my loving the richness of its colour, having got to know it in the trial bed I find it rather stiff and heavy and I want the asters here to dance and mingle and not weight the planting down.

The Aster turbinellus, for instance, has been retained for the space and the air between the flowers, as has Symphyotrichum ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ for its sprays of tiny, shell-pink flowers. I have also kept the late-flowering Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ for its modest habit and almost iridescent violet stars held on dark, wiry stems. I have always known that Aster umbellatus would feature in the planting, and so I lifted and split my three year old trial plant last autumn and divided it into six to bulk up this summer. There were many more that didn’t make the grade though, and I was torn about losing them, my self-discipline wavering at times. However, Jacky and Ian who help us in the garden eased my conscience by taking a number of the rejects home with them, and the space left behind, now that they are gone and I have finally committed, is ultimately more inspiring.

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

The reject asters

The reject asters

This is the second phase of rationalising the stock beds. In the spring, and to enable the preparation of the central bed, I split and divided the plants that I knew I would need more of come autumn, and lined these out in the top bed to bulk up; the lofty Hemerocallis altissima, brought with me from Peckham and prized for its delicate, night-scented flowers, the refined Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca, and the true form of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, originally divisions from plants in the Barn Garden at Home Farm which I planted in 1992.

I have not found a red day-lily I like more for its rustiness and elegance, and some of the ‘Stafford’ I have been supplied with more recently have notably less refined flowers and a brasher tone. I have planned for it to go amongst molinias so that the flowers are suspended amongst the grasses. Hemerocallis are easily divided and in the spring the stock plants were big enough to split into ten or so; the numbers I needed for their long-awaited integration into the planting. In readiness for setting out, and with the asters gone, we have now reduced the foliage of the daylilies by half, lifted them and then left them heeled in for ease of lifting and replanting.

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

The kniphofia and iris I had decided to keep went through the same process in March, and so the Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ and Iris magnifica were moved directly into their new positions where, just a week before, the sunflowers had towered. Similarly, the Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’ and Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’, which have both increased impressively, were lifted and moved into their new and final positions. This was in order to clear the old stock beds to make way for the autumn splits and keep the canvas as empty as possible so that I can see the space without unnecessary clutter when setting out.

The remaining trial rows – some Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield that I want in number and two white sanguisorba that will provide height and sparkle in the centre of the garden – were cut back to knee height, lifted and then split in text-book fashion with two border forks back to back to prise the clumps apart. Where the plants were not big enough I was careful not to be too greedy with my splits, dividing them into thirds or quarters at most.

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

Although October is the perfect month for planting, with warmth still in the ground to help in establishing new roots before winter, I have had to work around the trial bed of grasses and they now stand alone in the newly empty bed. Although I will be planting out pot-grown grasses next week, autumn is not a good time to lift and divide grasses as their roots tend to sit and not regenerate as they do with a spring split.

The plants I put in around the Milking Barn this time last year are already twice the size of the same plants I had to wait to put in where the ground wasn’t ready until the spring. I hope that the same will be true of this next round of planting, which will sweep the garden up to the east of the house and complete this long-awaited chapter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 October 2017

I am currently readying myself for the push required to complete the final round of planting in the new garden. The outer wrap went in at the end of March to provide the frame that will feather the garden into the landscape and, with this planting still standing as backdrop, I have been making notes to ensure that the segue into the remaining beds is seamless.

The growing season has revealed the rhythms and the plants that have worked, and the areas where tweaking is required. Whilst there is still colour and volume in the beds I want to be sure that I am making the right moves. The Gaura lindheimerei were only ever intended as a stopgap, providing dependable flower and shelter for slower growing plants. They have done just that, but at points over the summer their growth was too strong and their mood too dominant, going against much of the rest of the planting. This resulted in my cutting several to the base in July to give plants that were in danger of being swamped a chance, and so now they will all be marked for removal. Living fast and dying young is also the nature of the Knautia macedonica and they have also served well in this first growing season. However, their numbers will now be halved if not reduced by two-thirds so that the Molly-the-Witch (Paeonia mlokosewitschii) are given the space they need for this coming year and the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ the breathing room they require now that they have got themselves established.

Gaura lindheimerei

Gaura lindheimerei

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

I will also be removing all of the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ and replacing it with Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. I was so very sure when I had them in the stock beds that both would work in the planting but, once it was used in number, ‘Swirl’ was too dense and heavy with colour. The spires of ‘Dropmore Purple’ have air between them and this is what is needed for the frame of the garden not to be arresting on the eye and so that you can make the connection with softer landscape beyond.

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

As a gauzy link into the surroundings and as a means of blurring the boundary the sanguisorba have been very successful. I trialled a dozen or so in the stock beds to test the ones that would work best here. I have used Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ freely, moving them across the whole of the planting so their veil of tiny drumsticks acts like smoke or a base note. A small number of plants to provide cohesiveness in this outer wrap has been key so that your eye can travel and you only come upon the detail when you move along the paths or stumble upon it. Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, perhaps the best of the lot for its finely divided foliage, picked up where I broke the flow of the ‘Red Thunder’ and, where variation was needed, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ has proved to be tireless. Smattered pinpricks, bright mauve on close examination but thunderous and moody at distance, are right for the feeling I want to create and allow you to look through and beyond.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

The gauze has been broken by plants that draw attention by their colour being brighter or sharper or the flowers larger and allowing your eye to settle. Sanguisorba hakusanensis (raised from seed I brought back from the Tokachi Millennium Forest) with its sugary pink tassels and lush stands of Cirsium canum, pushing violet thistles way over our heads. The planting has been alive with bees all summer, the Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, now on its second round of flower after a July cutback, and the agastache only just dimmed after what must be over three months ablaze. Agastache ‘Blackadder’ is a plant I have grown in clients’ gardens before and found it to be short-lived. If mine fail to come through in the spring, I will replace them regardless of its intolerance to winter wet, as it is worth growing even if it proves to be annual here. Its deep, rich colour has been good from the moment it started flowering in May and, though I can tire of some plants that simply don’t rest, I have not done so here.

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

The lighter flashes of colour amongst the moodiness have been important, providing a lift and the key into the brighter palette in the plantings that will be going in closer to the house in a fortnight. More on that later, but a plant that will jump the path and deserves to do so is the Nepeta govaniana. I failed miserably with this yellow-flowered catmint in our garden in Peckham and all but forgot about it until I re-used it at Lowther Castle where it has thrived in the Cumbrian wet. It appears to like our West Country water too and, though drier here and planted on our bright south facing slopes, it has been a truimph this summer.

Nearly all the flowers in the planting here are chosen for their wilding quality and the airiness in the nepeta is good too, making it a fine companion. I have it with creamy Selinum wallichianum, which has taken August and particularly September by storm. It is also good with the Euphorbia wallichii below it, which has flowered almost constantly since April, the sprays dimming as they have aged, but never showing any signs of flagging.

Nepeta govaniana

Nepeta govaniana

Selinum wallichianum

Selinum wallichianum

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

I have rather fallen for the catmints in the last year and been very successful in increasing Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ from cuttings from my original stock plant. I plan to use the softness of this upright catmint with the Rosa glauca that step through the beds to provide another smoky foil.

Jumping the path and appearing again in the planting that will be going in in a fortnight are more of the Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’. True to its specific name, this pretty, white calamint seems happy to seed around in cool places and I have used it, as I have the Eurybia diviricata, as a pale and cohesive undercurrent. They weave their way through taller groupings to provide an understory of lightness, breathing spaces and bridges. Both of these are on the autumn order and will jump again into the new palette I have assembled to provide a connection between the two.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 October 2017

A month ago I was in Japan, on my annual visit to the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been working at the forest for sixteen or seventeen years now and the yearly journey is always rewarding. It is a place with a big vision, where half the side of a mountain and the forested foothills are the domain. It has the feeling of the north, with air that slips over the mountains from Russia not so far away. Bears really do live in the woods and the landscape freezes to minus twenty-five, under a blanket of pristine white from early November through to the end of April.

The owner, Mitsugishe Hyashi, bought the land with the ambition of offsetting the carbon footprint of his newspaper business, but the park represents far more than this. He also set out for it to be sustainable for the next thousand years and it is a privilege to have been part of this vision and to be a small part in shaping the park’s direction.

The gardens and the managed forests are a big part of helping to communicate the big idea to visitors. The gently managed places, which take the rough edges off the wilderness, are part of making people feel comfortable in the areas that are accessible. Takano Landscape Planning, which put together the original masterplan, knew that the people and their comfort in the environment were important and, when I was asked to be part of the project in 2000, it was to help with creating a series of spaces that would provide the landscape with a focus for the public.

The Earth Garden

The Earth Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Rose Garden

The Rose Garden

In their turn, the gardens we have since created have been key in making a ‘safe’ place and a link with the magnitude of the landscape, to literally ground the visitor in the place. A landform called the the Earth Garden, which reconfigured a clearance field that separated the visitor from the mountains, was the first of the projects to come to fruition. A series of grassy waves, echoing the undulations of the mountains beyond, now provides the visitors with a ‘way into’ the landscape. By exploring the earthworks they soon find themselves at the base of the mountains or at the edge of a mountain stream or a trail into the woods. The landforms extend to wrap another five hectares of cultivated garden, and area named the Meadow Garden, which was planted to celebrate the official opening ten years ago. Beyond that there is the Farm Garden where people can see a modestly-sized productive space with fruit, vegetables and cutting flowers and eat food grown there at the cafeteria. A goat farm producing cheese is the backdrop to this space, while most recently we have developed a Rose Garden of hybrid and species roses suitable for a northern climate and an orchard to test growing apples and other top fruit this far north.

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest, where Fumiaki Takano had already made a start when I was brought on board, eases visitors in with soft bark paths and decked walkways that take them back and forth across the rush of mountain water that switches between the trees. The low native bamboo Sasa palmata, which took over the forest after its balance was disturbed when all of the oak was logged at the turn of the last century, has been carefully managed to encourage a more diverse regeneration of the forest floor. Repeated cutting in the autumn, coupled with the short summers that curtail its regrowth and stranglehold, has been diminished enough for the window of opportunity to be given back to other plants in the native seedbank. Wave upon wave of indigenous plants now greet the visitors. Anemone, Caltha palustris var. nipponica and Lysichiton camtschatcense seize the window after snow melt and, as oak woodland comes to life, the race continues with Trillium, scented-leaved and candelabra primulas and arisaema. By the time I arrived in late July, the woodland was tall with giant-leaved meadowsweet, cardiocrinum and lofty Angelica ursina.

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Filipendula camtschatica

Filipendula camtschatica

The Meadow Garden (main image), my primary focus with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani, was inspired by the woodland and the way the plants have found their niche and live together in successive layers of companionship. Sitting on the fringes of the wood where dappled light meets sunshine, it is divided into two main parts by a meandering wooden walkway. The lower areas emulate the edge of woodland habitats, while above the path the planting basks in full sunshine. The planting is further divided by swathes of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, which separate the different colour fields, so that the yellows are held back as a surprise. The movement of the mountain winds is caught in their plumage to animate the garden.

The plantings integrate Japanese natives with plants from other regions of the world that have similar climates. North America and parts of northern Europe provide the ‘exotic’ layer in the garden and their inclusion draws attention to the Japanese natives that are mingled amongst them. Plants such as the Houttuynia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Aralia cordata. Everyday plants in Japan that are given a new focus. In terms of my own gardening process, these plants were the exotics and it has been such a fascinating process to reverse my experience of the exotic/native balance. Native Lilium auratum, the Golden-Rayed Lily of Japan, and the giant meadowsweet, Filipendula camtschatica, are teamed with Phlox paniculata ‘David’. Sanguisorba hakusanensis, the extraordinary pink, tasselled burnet is in company with Valeriana officinalis and Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’.

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

The original planting plans were designed as a number of individual mixes, planted in drifts to allow the planting to flow across the site. Each mix contained a small number of species, usually five to seven, that were planted completely randomly. The percentages in the mix were critical, with a small number of emergent plants such as the Cephalaria gigantea to rise above larger percentages of individuals that would knit and mingle at lower and mid-level. Now that I look back it was a brave move, because it was entirely dependent upon the head gardener to steer and monitor.

Midori has been more than I could have hoped for in an ally on the ground and our yearly critique and analysis of the plantings is a high level conversation that looks both at the big picture and also at the detail. Of course, there have been adjustments to refine each mix as they change yearly with plant lifespans, climate and vigour, which drive our response. But we have also needed to make changes to keep the garden moving forward, introducing new plants and swapping or reducing the numbers of those which have become dominant. For instance, we have found plants that will happily coexist in a demanding matrix of twenty five companions in the wild, can take their opportunity to dominate when given just a handful of company.

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Last year, to challenge the thousand year brief of sustainability, a tornado swept across the island. It hit last summer, just before I visited and I arrived to see the carnage. The mountain water had swelled the streams that braid the site to rip and tear and deposit a silver sand from afar and boulders that are now new features. Miraculously the waters divided to either side of the Meadow Garden, but they swept away all but two of the bridges, which have never been found. We were left feeling very small and of little consequence within the time frame that had been set for the preservation of this place.

The repairs have been slow but sure and in scale with what is possible. New shingle banks have been embraced as the new places and opportunities that they are. Already they are being colonised. It is the gardener’s way to repair and to move on, but we have been humbled nevertheless. Midori walked me through the garden, pointing out ‘weeds’ that have been swept in to the planting that were never there before. And there are anomalies that are hard to get to grips with that point to changes of another scale. Some plants have taken a hit a year later to sulk or fail, and we do not know why, whilst others have seized life with a new vigour as if the charge from the mountain has revitalised them. With ten years under our belts and the knowledge we have gained that is specific to this place, we are adjusting again and moving on. On to a second decade and the certain changes that we will be responding to, to move with it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Kiichi Noro and Syogo Oizumi

Published 16 September 2017

The meadows that were cut for hay in the middle of July are already green and lush after the August rains. The hay needs to be cut before the goodness goes out of it, but we leave it until the yellow rattle rattles in its seedpods and has dropped enough seed for next year. With the cut go a host of summer wildflowers which have already set seed. Those that mature later are lost with the cut. So in the fields that are put to grazing when the grass regenerates after the hay cut, we will not see the scabious or the knapweeds. If they are present at all, they will not get the chance to seed and, if we were to have orchids, (one day, hopefully) their cycle would also be curtailed as they are only now ripening.

Where the land is too steep for the tractor, we find ourselves with rougher ground and other habitats. The steep slopes dipping away and down from The Tump are left uncut and, with the sheep shaping their ecology, they have become tussocked and home to a host of wildlife that has made this protected place home. The marsh thistle likes it there and can compete, and slowly we are seeing the first signs of woodland, with hawthorn and ash sheltering in the creep of bramble. We will have to make a decision as to where we apply a hand in preventing the woody growth from encroaching upon the grassland, as all the habitats have their merit.

The lower slopes of the Tump above the ditch where the meadowsweet grows are colonised by marsh thistle

The lower slopes of the Tump above the ditch where the meadowsweet grows are colonised by marsh thistle

Marsh Thistle (Cirsium palustre)

Marsh Thistle (Cirsium palustre)

The field that climbs steeply immediately behind the house is raked off by hand after the farmer mows it for us. It is too steep to bale so it is cut late to allow an August flush of meadow life. It is a task raking the cuttings to keep the fertility down, but one that is getting easier each year with concerted efforts to colonise the grass with the semi-parasitic rattle. This field and the newly seeded banks that sweep up to the house are valuable for being late and, as I write on a breezy bright day in a wet August, it is alive with the latecomers and the host of wildlife that retreats to find sanctuary there.

The ‘between places’ that are formed by banks that are just too steep to manage occur along the contours and below the hedges that run along them. The precipitous slope (main image) between our two top fields (The Tynings) has been something of a revelation and, seven summers in, we are seeing the rewards of making an effort with its management. A neighbour told us that every twenty years or so the farmer before us would fell the ash seedlings that took the banks as their domain. This must have last happened five or six years before we arrived and, although it was then covered in young ash and bramble, it was clear that this south-facing slope had the potential to be more than just scrub, and provide a contrast to the grazed meadows. The second winter we were here, we cleared the bramble, cutting off great mats and rolling them down to the bottom of the slope like thorny fleeces.

The Tynings bank in April with cowslips showing

The Tynings bank in April with cowslips showing

That spring the newly exposed ground immediately gave way to cowslips and violets that had been sheltering amongst the brambles. In the summer they were followed by smatterings of wild marjoram, field scabious, common St. John’s Wort, crow garlic, hedge bedstraw and agrimony, indicating the limey ground and the south-facing position.

Why the field levels vary so dramatically to either side of the contour-running hedge is intriguing. The ground in the valley is prone to slipping and the twenty-foot slope between these two fields suggests the occurrence of something of that nature in the past. The steepness of the bank and the shale and the clay that has been exposed in the underlying strata make it incredibly free-draining and the plants that have colonised here are specific and a contrast to those found on flatter ground. If you walk along the bank on a hot day now it is full of marjoram and you can hear it hum with life and crack and pop as vetch pods scatter their seed.

Field Scabious (Knautia arvensis) and Wild Marjoram (Origanum vulgare)

Field Scabious (Knautia arvensis) and Wild Marjoram (Origanum vulgare)

Agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria)

Agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria)

Common Knapweed (Centaurea nigra)

Common Knapweed (Centaurea nigra)

We have given the bank a ‘year on, year off’ cut, strimming in the depths of winter when the thatch is at its least resistant. All the cuttings are roughly raked to the bottom of the slope (and then burned) so that there is plenty of light and air for regeneration. We leave the spindle bushes, the wild rose and a handful of ash seedlings, but the sycamore seedlings that proliferate from the large trees in the hedgerow are cut to the base to keep them from getting away. After three cuts over six years the bank is now thick with marjoram and scabious, hedge bedstraw, common and greater knapweeds and this year, wild carrot, one of my favourite umbellifers for late summer. It is abuzz with honeybees, bumblebees, hoverflies and butterflies.

This bank has been the inspiration for the newly-seeded slopes around the house and last year I gathered seed from here to grow on as plugs to bulk up the St. Catherine’s seed mix that went down last September. The seed is sown fresh, as soon as it is gathered, into cells and left in a shady place for a year. I have not thinned the seedlings and have deliberately grown them tough so that they are able to cope with the competition. Last year’s batch was planted out not long after the banks were sown to add early interest, and some are visible and flowering already.

Crow garlic (Allium vineale)

Crow garlic (Allium vineale)

Greater Knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa)

Greater Knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa)

Common St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Common St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Hedge Bedstraw (Galium album)

Hedge Bedstraw (Galium album)

This year’s plugs, which are destined for the late meadow behind the house, will be put out in September, straight after the banks have been cut. We have already seen a difference in the wildlife since creating these wilder spaces up close to the buildings, with more swallows than before swooping low for insects, the increased presence of a pair of breeding kestrels, a red kite that formerly kept itself to the farther end of the valley, more bats and, a couple of weeks ago, an exciting moment when a barn owl came sweeping low over the banks as dusk fell. Every year, with careful management, we will see a successive layer of change, and one year in the not too distant future, a sure but certain enrichment.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 12 August 2017

The new planting went in on the spring equinox, a week that saw the energy in the young plants shifting. Just seven days later the emerging fans of the hemerocallis were already splayed and flushed, and the signs were also there in the tightly-clasped crowns of the sanguisorba. The chosen few from my trial in the stock beds had to be split to make up the numbers I needed, but energy was on their side and, once in their new home, they seized life quickly to push new foliage.

We mulched the beds immediately after planting to keep the ground clean and to hold in the moisture whist the plants were establishing. Mulching saves so much time in weeding whilst a garden is young and there is more soil than knit of growth. This year I was also thankful because we went into five long weeks without rain. I watered just once, so that the roots would travel down in search of water, but once only so that they did not become reliant. The mulch held this moisture in the ground and the contrast to the old stock beds that went without has been is remarkable. Spring divisions that went without mulch have put on half as much growth and have needed twice as much water to get the same purchase. I can see the rigour of my Wisley training in this last paragraph, but good habits die as hard as bad ones.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

17 June 2017

17 June 2017

Since it rained three weeks ago, the growth has burgeoned. As the summer solstice approaches the dots of newly planted green that initially hugged the contours of our slopes have become three dimensional as they have reared up and away into early summer. I have been keeping close vigil as the new bedfellows have begun to show their form, noting the new combinations and rhythms in the planting. Information that I’d had to hold in my head while laying out the hundreds of dormant plants and which, to my relief, is beginning to play out as I’d imagined.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

16 June 2017

16 June 2017

Of course, there are gaps where I am waiting for plants that were not then available, and also where there were gaps in my thinking. There are combinations that I can see need another layer of interest, and places where the plants are already showing me where they prefer to be. The same plant thriving in the dip of a hollow, but not on a rise, or vice versa. Plants have a way of letting you know pretty quickly what they like. At the moment I am just observing and not reacting immediately because, as soon as the foliage touches, the community will begin to work as one, creating its own microclimate that will in turn provide influence and shelter. I lost my whole batch of Milium effusum ‘Aureum’, which I put down to the exposure on our south-facing slopes. However, most of them have managed to set seed, so I am hoping that next spring the seedlings will find their favoured positions to thrive in the shade of larger, more established perennials.

The wrap of weed-suppressing symphytum that I planted along the boundary fence is already knitting together, and I’m happy to have this buffer of evergreen foliage to help prevent the landscape from seeding in. However, a flotilla of dandelion seed sailed over the defence and are now germinating in the mulch. We saw them parachuting past one dry, breezy day in April as if seeking out this perfect seedbed. They are easy to weed before they get their taproot down and will be less of a problem this time next year when there will be the shade of foliage, but they will be a devil if they seed into the crowns of plants before they are established. A community of cover is what I am aiming for, so that the garden starts to work with me, and time spent protecting it now is time well spent.

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

The comfrey is planted in three drifts. Symphytum grandiflorum, S. ‘Hidcote Blue’ and S. g. ‘Sky Blue Pink’. The latter is new to me and I’m watching carefully that they aren’t too vigorous. I’ll have to keep an eye on the next ripple of plants that are feathered into the comfrey from deeper into the garden as the symphytum can also be an aggressive companion. The Sanguisorba hakusanensis should be able to hold their own, as they form a lush mound of foliage, and the Epilobium angustifolium ‘Album’ should be fine, punching through to take their own space. I’ll clear the young runners where the creep of the comfrey meets the gentler anemone and veronicastrum.

The ascendant plants were placed first when laying out and will form a skyline of towers through which the other layers wander. They are already standing tall and providing the planting with a sense of depth. Thalictrum ‘Elin’ is my height already, a smoky presence of foliage and stems picking up the grey in the young Rosa glauca and proving, so far, to not need staking. This is important, because our windy hillside provides its challenges on this front. Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ has also provided immediate impact, its limbs inky dark and the mauve of the flowers giving early colour and contrast to the clear, clean blue of the Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’. Next year the garden will have knitted together so that the contrasts will work against foliage or each other, but for now the eye naturally focuses not on the gappiness, but where things are beginning to show promise.

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

There have been a couple of surprises already, with a fortuitous mix up at the nursery reavealing a new combination I had not planned for with a drift of Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’ coming up as S. nemorosa ‘Amethyst’. I am very particular about my choices and I’d planned for ‘Indigo’ since growing it in the stockbeds, but the unexpected arrival of ‘Amethyst’ has, after my initial perplexity, been a delight. I’ve not grown it before, and I like its earliness in the planting and how it contrasts with the clear blue of the Iris sibirica with a little friction that makes the eye react more definitely than with the blue of ‘Indigo’. I like a little contrast to keep zest in a planting. The Euphorbia cornigera, with their acid green flowering bracts, are also great for this reason with the first magenta of the Geranium psilostemon.

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

As the last few plants that weren’t ready in the nursery become available, I’m wading back into the beds again to find the markers I left there when setting out so that I can trace my original thinking. I am pleased to have done this, because it is very easy to start to reshuffle, but the original thinking is where cohesiveness is to be found. Changes will come later, after I’ve had a summer to observe and see where the planting is lacking or needing another seasonal lift. I can already see the original perennial angelica has doubled in diameter, and I’ve added eight new seedlings which, if left, will be far too many so a few removals will be necessary comer the autumn. Patience will be the making of this coming growing season, followed by action once I can see my plans emerging.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 June 2017

There is a point when winter turns and spring takes over. It inches at first, and then that false feeling – that you have time on your hands – begins to evaporate. This year I have been watching for the change more intently than usual, because we had a date in the diary to plant up the first phase of the new garden; the week of the spring equinox which, this year, proved to be perfect timing. One week later and the peonies were already a foot high and the tight fans of leaf on the hemerocallis were flushed and beyond moving without setting them back.

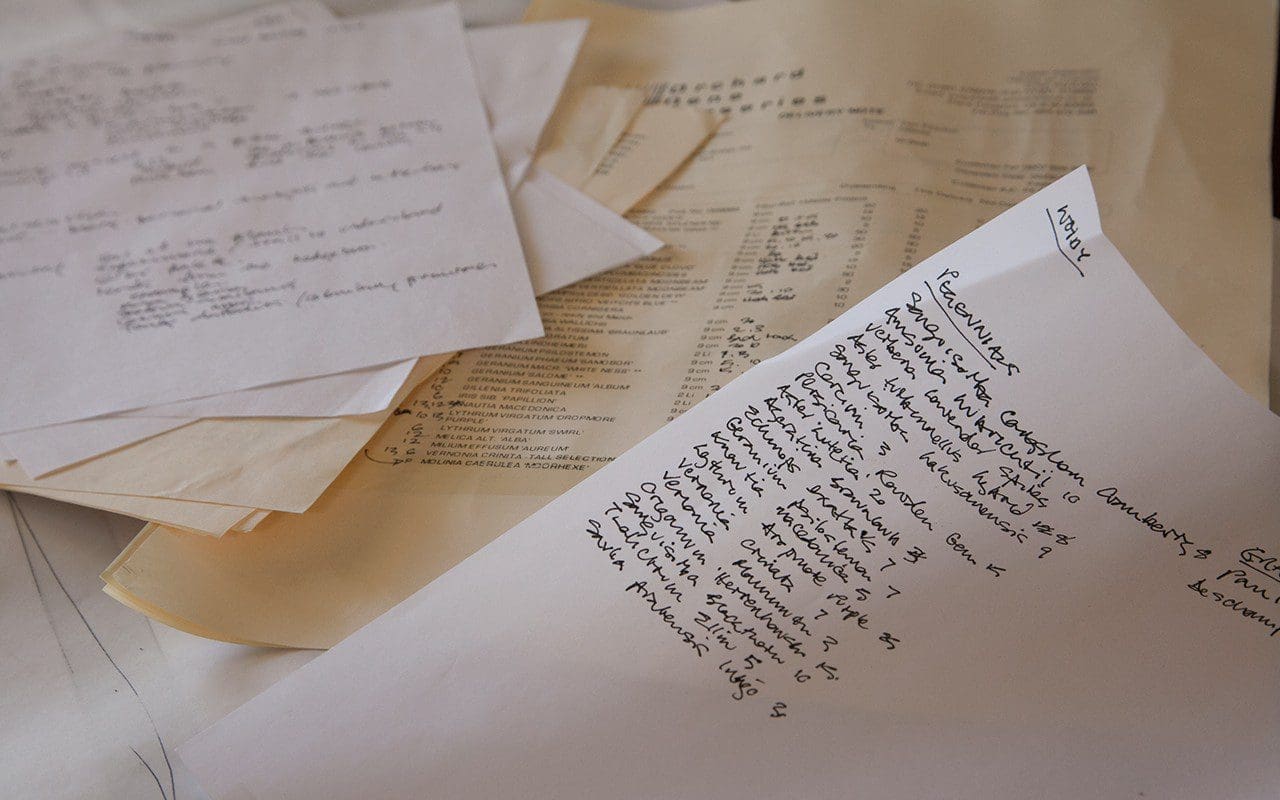

I have been planning for this moment for three years, perhaps longer in refining the idea of the way I wanted the planting to nestle the buildings and blend with the land beyond. I procrastinated over the final plant list for as long as it was possible, but in January it finally went out to the nurseries in time to get the stock I needed for spring.

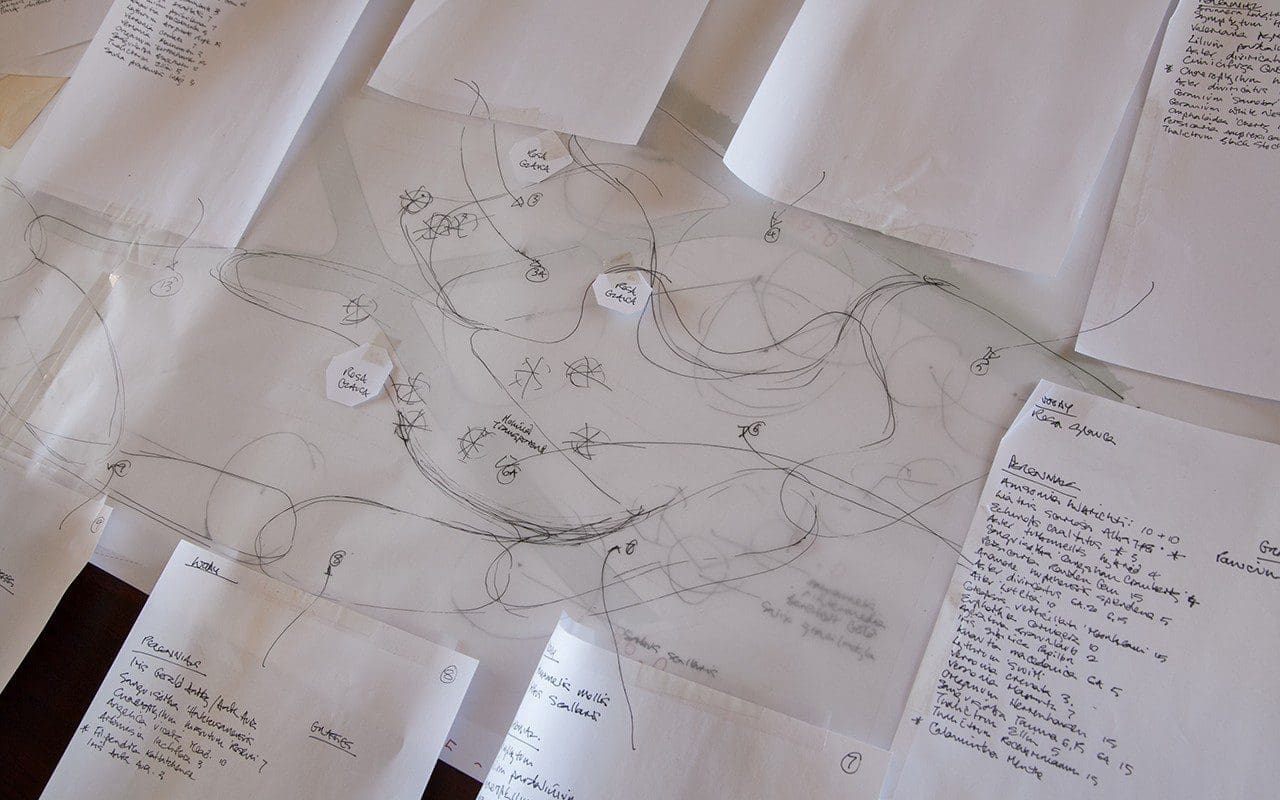

The process of refining a plant palette is one that I know well, but committing a plan to paper is an altogether more difficult thing to do for yourself than for a client. I decided not to make an annotated plan, but instead to map a series of areas that shift in mood as you walk the paths. I paced the space again and again to understand where the ground was most exposed, where it was free-draining and to note that, in the hollow where the ground swung down to the track, there was running water a spit deep this winter. I imagined where I would want height and where I would need the planting to dip, sometimes deep into the beds, to give things breathing space. There would also need to be countermovements across the site, with tall emergent plants brought to the foreground, close to the paths.

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The preparation was completed the week before the plants arrived; the soil dug in the windows when it was dry enough and then knocked out level just in time. We prayed that the weather would dry up, because the soil had lain wet all winter and would not stand footfall if it stayed that way. In tandem with the soil preparation we moved some favourites that I have been bulking up, like the Paeonia mlokosewitschii and Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’, both of which came with us from Peckham, and split those plants that had passed the test in the trial garden. A three year old Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ was easily divided into eight, and so three plants gave me twenty four to play with; enough to move from bed to bed and to jump the path. The same with the persicarias, the Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’, the Aster turbinellus and a long list of others. These were bagged up individually so that I could afford to leave them laid out when shifting the planting around on the day of laying out.

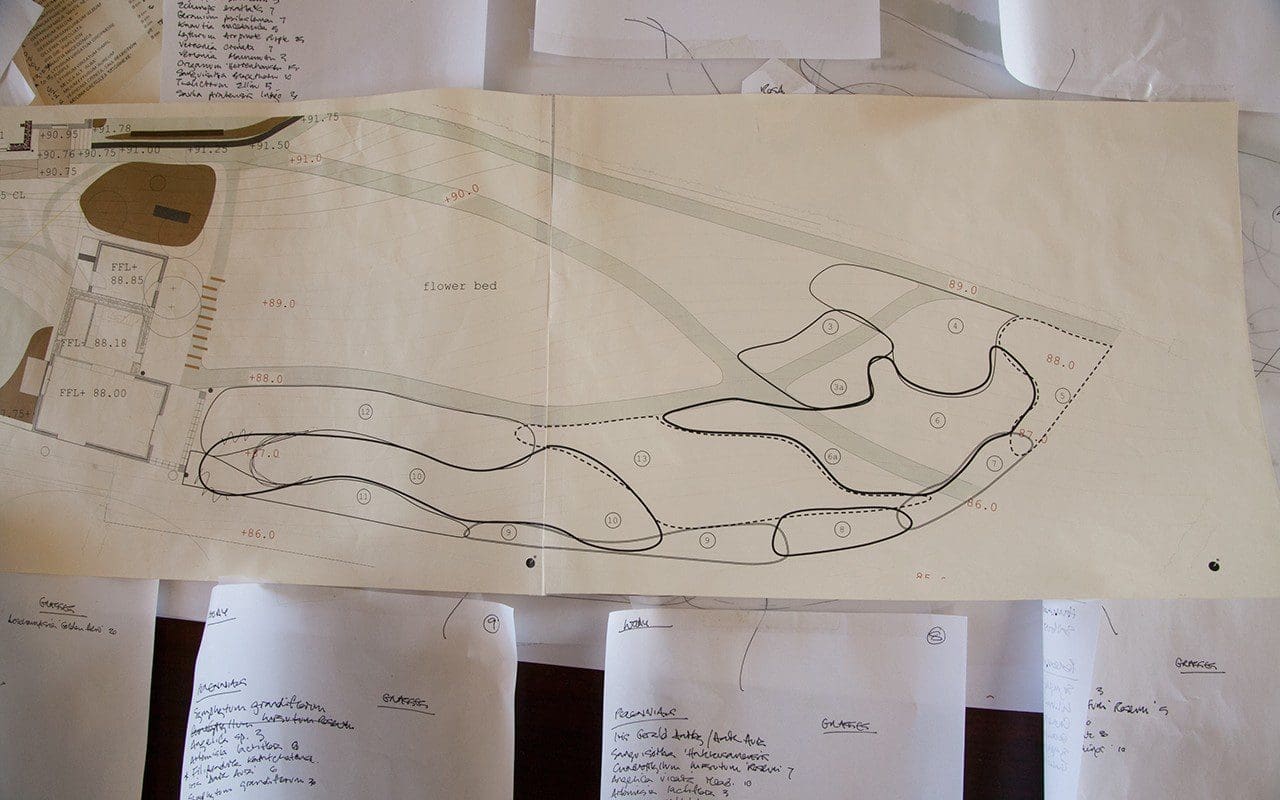

Due to the size of the site this was just the first round of planting, and of only half the garden. The remaining half will be planted this autumn. The plan for this lower half comprises a dozen interlocking areas, which allow my combinations to vary subtly across the site and flow into one another to form a related whole. Before starting, the boundaries were sprayed onto the soil with a landscape marker, although I break these boundaries during setting out, jumping plants across to knit them together.

Shrubs and woody plants were positioned first to articulate the space. Trees by the gates including Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’ and Crataegus coccinea, some Malus transitoria and Rosa glauca breaking in from high up, and home-grown whips of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Salix gracilistyla fraying the edges alongside the field. Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’, the largest of the clump forming grasses, was also given its position early to tie the meeting point of the paths together.

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Plant lists and orders

Plant lists and orders

For each of the zones I made a list that quantified all of the plants I would need to make it special. A handful of emergents to rise up tall above the rest; Thalictrum ‘Elin’, Vernonia crinata, sanguisorbas and perpetual angelicas. When laying out these were the first perennials placed to articulate the spaces between the shrubs and key grasses.

Next, the mid-layer beneath them, with the verticals of Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Rowden Gem’, and the mounding forms of aster (A. divaricatus) or geranium (G. phaeum ‘Samobor’, G. psilostemon and G. ‘Salome’). The plants that will group and contrast. And finally, the layer beneath and between, to flood the gaps and bring it all together. These were a freeform mix; fine Panicum ‘Rehbraun’ with Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Tanna’, or Viola cornuta ‘Alba’, Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ and the white bloody cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum ‘Album’.

The plants arrived from Orchard Dene Nurseries and Arvensis Perennials on the Friday. Immaculate and ready to go and filling up the drive. I like to plant small with nine centimetre pots. If you get the timing right, and don’t have to leave them sitting around, this size is easily trowelled in with minimum soil disturbance. At close spacing this makes planting easier and faster than having to spade in a larger plant.

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants grouped by planting zone

Plants grouped by planting zone

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

It took us two days to complete the lifting and dividing of my stock plants and to set the plants on the paths in their groups. And the process was prolonged as I started adding last minute choices from the stock beds. On the Sunday high winds whistled through the valley to dry the soil, so I started setting out and hoped that the pots didn’t blow into one corner overnight, as once happened in a client’s garden. On the Monday, and ahead of my team of planters who were arriving the next day, I continued to populate the spaces, between the heavens opening up and pouring stair-rods. It was hard, and there was a moment I despaired of us being able to get the plants in the ground at all.

Setting out plants is one of the most all-consuming and taxing activities I know. It feels like it uses every available bit of brain-space. You not only have to retain and visualise the various volumes, cultural requirements and habits of the individual plants, but also the sequencing and rhythm of a planting, how it rises and falls, ebbs and flows, and then how each area of planting relates to the next, in three dimensions and from all angles. Add to this the aesthetic considerations of colour relationships both within and between areas and the time-travel exercise of imagining seasonal changes and there is only so much I can do in one session. However, I was ahead of my planters and, as long as I could hold my concentration once they arrived, it would stay that way with them coming up behind me. The rains abated, the wind continued and the following day the soil was dry enough for planting.

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Jacky Mills

Jacky Mills

Ian Mannall

Ian Mannall

Ray Pemberton

Ray Pemberton

On the 21st, the sun broke through not long after it was up. A solitary stag silhouetted against the sky looked down on us from the Tump as we readied for the day. Clearly word had already got out that there were going to be rich new pickings in the valley.

Over the course of two days about twelve hundred plants went in the ground. Three people planting and myself managing to stay ahead, moving the plants into position in front of them. Thank you Ian, Jacky and Ray for your hard work, and Huw for supplying a constant supply of necessary vittles.

I cannot tell you – or perhaps I can to those who know this feeling too – what a huge sense of excitement is wrapped up in a new planting. Plans and imaginings, old plants in new combinations, new plants to shift the balance. All that potential. All those as yet unknown surprises.

Already, the space is changed. We will watch and wait and report back.

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The bare-root plants arrived at the end of November, bagged up at the nursery as soon as the foliage fell from the branches and bundled together ready to make the move to new ground. Just an hour after delivery the roots were plunged in the trough to rehydrate them and then the bundles lined out in a trench in the kitchen garden until I was ready to plant them in their final positions. I love this moment, which marks the transition between the activity of a garden tended through the growing season to the industry of winter preparation. It is now that the real work is happening. As we turn the soil to let the frost do the work of preparing it for spring planting, or spend an hour shaping the future of a new tree so that its branches are given the best possible opportunity, we imagine the growing garden fully-clothed and burgeoning. Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan It has been an exciting autumn, and one that I have looked forward to and been planning towards for the past six years. It has taken this long to resolve the land around the house. First to feel the way of the place and then to be sure of the way it should be.

Though the buildings had charm, (and for five years we were happy to live amongst the swirly carpets and floral wallpapers of the last owner) the damp, the white PVC windows and the gradual dilapidation that comes from years of tacking things together, all meant that it was time for change. Last summer was spent living in a caravan up by the barns while the house was being renovated. We were sustained by the kitchen garden which had already been made, as it provided a ring-fenced sanctuary, a place to garden and a taste of the good life, whilst everything else was makeshift and dismantled.

This summer, alternating between swirling dust and boot-clinging mud, we made good the undoings of the previous year. Rubble piles from construction were re-used to make a new track to access the lower fields and the upheavals required to make this place work – landforming, changes in level, retaining walls and drainage, so much drainage – were smoothed to ease the place back into its setting.

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

Of course, it has not been easy. The steeply sloping land has meant that every move, even those made downhill, has been more effort and, after rain, the site was unworkable with machinery. We are fortunate that our exposed location means that wet soil dries out quickly and by August, after twelve weeks of digger work and detail, we had things as they should be. A new stock-proof fence – with gates to The Tump to the east, the sloping fields to the south and the orchard to the west – holds the grazing back. Within it, to the east of the house and on the site of the former trial garden, we have the beginnings of a new ornamental garden (main image). An appetising number of blank canvasses that run along a spine from east to west

The plateau of the kitchen garden to the west has been extended and between the troughs and the house is a place for a new herb garden. Sun-drenched and abutting the house, it is held by a wall at the back, which will bake for figs and cherries. The wall is breezeblock to maintain the agricultural aesthetic of the existing barns and, halfway along its length, I have poured a set of monumental steps in shuttered concrete. They needed to be big to balance the weight of the twin granite troughs and, from the top landing, you can now look down into the water and see the sky.

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

On the lower side of the new herb garden, continuing the bank that holds the kitchen garden, the landform sweeps down and into the field. Seeded at an optimum moment in early September, it has greened up already. Grasses were first to germinate, and there are early signs of plantain and other young cotyledons in the meadow mix that I am yet to identify. I have not been able to resist inserting a tiny number of the white form of Crocus tommasinianus on the brow of the bank in front of the house. There will be more to come next year as I hope to get them to seed down the slope where they will blink open in the early sunshine. I have also plugged the banks with trays of homegrown natives – field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and divisions of our native meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) – to speed up the process of colonisation so that these slopes are alive with life in the summer.

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September