ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY REGISTERED OR A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

The Giant Oat Grass inhabits high, dry ground in southern Europe and, although I have never seen it in the wild, I can imagine them rising above their companions in the steppe. This is how they like to be, in the company of plants that do not overshadow the tussock of evergreen foliage and where in the longest days of the year they take the light and hold it in a hovering suspension of coppery awns.

The stipa is an old favourite. I grew it first and en masse as an early emergent in the Barn Garden at Home Farm. We used the pockets amongst the old cobbles where previous buildings had been razed to the ground and allowed the oat grass to lead the mood in June. I let the Californian poppy seed through a sprawl of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ at its feet and the rusty spears of Digitalis ferruginea ascended up into the cloud to score the vertical. I have the Stipa here too, also by our barns and growing in nothing but rubble and subsoil where they stand head and shoulders above their companions. To play on the dilapidated mood of the rusty buildings they are teamed with evening primrose and the tiny pinpricks of a wild dianthus.

Spearing at speed from the basal foliage as the days lengthen, the stipa are a litmus in this race to the longest day. Angling up and out so that there is sufficient room for the flowers to take their own space when they break the tall tapers, they head into a miraculous fortnight of flower. The panicles open out at head height to form a cage through which the wind can easily pass. The golden moment is the week the anthers furnish themselves with pollen, dangling free and on tiny hinges for mobility and ease of distribution for wind-blown pollen.

Though it strikes a particular mood of dry airiness in the garden, Stipa gigantea goes with almost anything if you pick it and bring it inside for closer observation. We have it here with a couple of neighbours from the planting. A tall Dianthus giganteus from the Balkans, which favours the same conditions and seeds about in the open places. It has proven to be long-lived here where the ground drains freely and has seeded easily but not annoyingly amongst but not into the crowns of neighbouring plants. Rising to almost a metre here, it is an easy companion, content to find its place on the edge of the planting and rising through the stipa to provide an undercurrent of colour. With blood red calyces and magenta buds that deepen the mood, the flowers open a soft rose-pink.

Close by, but very much in their own space, are the Baptisia x variicolor ‘Twilite Prairieblues’. Where many perennials are happy to be moved if you don’t find them the right position, you need to place the False Indigo in the right place the first time, because they like to put their feet down and hate disturbance thereafter. Being leguminous they fix their own nitrogen and are happy in the rubbly soil. As prairie-dwellers they hate to be overshadowed and will dwindle if a neighbour throws shade, but given a place they like with the surround of good light, they are long-lived and easy.

I have been experimenting with several of the hybrids for their longevity and their curious in-between colours and this one is a beauty. The female parent is the more usual indigo blue B. australis, but the male parent here is the yellow flowered B. sphaerocarpa and this provides the yellow keel. The colour of the standards is neither one thing nor another. A smoky violet-purple, without being muddied.

Rising fast and tall and again racing to the solstice, the lupin-like flowers strike a vertical accent whilst in flower. As they go to seed the plant becomes a rounded form that you need to allow room for as it fills out as it matures. The presence in summer is strong and definite, with good healthy glaucous foliage and, later, long-lasting seedpods that darken in winter to charcoal-black.

Though from the altogether different growing conditions of the cool damp meadows of southern China, the Iris chrysographes ‘Black Form’ refers here to the winter colours of those baptisia seedpods. Though iris could become a serious obsession, the reappearance of this one every June is always spellbinding. Black on first appearance, but the deepest royal purple on closer observation, they are worthy of a backdrop against which they will not be lost. In the garden they are allowed to hover in the paler suspension of Bowles’ Golden Grass, where their beautiful form is made all that much clearer. And here too, the stipa shows us that it is worth experimenting with associations you might not choose for their cultural compatability, but for what they might inspire beyond their place in the garden.

Words: Dan Pearson | Flowers and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 June 2021

The oriental poppies have broken the green, rearing above the rush of June foliage. They are the first true colour in the garden, save the Tulipa sprengeri that teetered neatly on the last week of spring and preceeded them. Red is a jolt this early in our verdant landscape, but we are ready for it now, the first slash of summer.

I have planted the poppies in homage to several memories. The first, a plant I remember from being about the same height, gazing into their interiors in our childhood garden. It grew with ferns and sprawled beyond the borders to offer up bristly buds, the casing breaking into two under the pressure of soon to be uncrumpled flower. I am red-green colour blind, but not completely and those poppies are an early memory of being able to see red fully, for they present it without compromise. Luminous and as red as anything can be, heightened by black-blotched bases and turquoise stamens.

The second memory, and one that I have planted into this garden, refers not to poppies at all but to meeting scarlet Amenone pavonina flaring amongst euphorbia and the march of giant fennel on the Golan Heights in Israel. I was there for a year working in the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens and the brilliant Michael Avishai, then Director of the gardens, would take me on weekend excursions to look at the flora of Israel. A fearless and terrifying driver, we would leave at 4am, to arrive at a site, spot on time for a happening in the landscape. This one came with his advice to not stray too far from the road. If you stepped over the wire marked “Land mines. Do not enter !”… The red of anemone I can see too and I shall never forget its shimmer amongst its opposite acid greens and the sun rising over an army of fennel stretching into a dangerous distance.

So, this particular memory comes with a charge and the oriental poppies that step through the giant fennels in the garden here take the place of the anemone. We have two varieties by default, not design. The requested ‘Beauty of Livermere’ (Goliath Group) are pillar box red, while there are three plants of a tangerine orange one that were substituted and planted without knowledge of their difference. I do not have the heart nor the desire to take out one or the other. The reds are good together and if I were to try and remove the plants to only have one, they would still likely regrow from root cuttings. This is the way to propagate oriental poppies for they do not come true from seed.

The rush into life in the spring, first with a mound of hairy, lime-green foliage and then the reach to flower is made possible by energy stored in thick, deeply searching roots. Hailing from Central Asia, their habit of disappearing once they have flowered and set seed is a survival mechanism against the drought of summer. The gap they leave will need to be negotiated by cutting the plants back to the base as soon as they begin to wane and in combining them with later-to-come perennials that will cover for the gap they leave behind. Asters and late flowering grasses make good couplings.

The reserve in the root can also be used to advantage in the fringe of the garden in rough grass and amongst cow parsley for the early growth will also outcompete grass in spring. The secret is to introduce them as established plants and keep them clear of competition in the first year whilst they are building their root system. Their dwindling summer growth will be disguised by the meadow and the autumn regrowth can be mowed around once it returns with summer rains.

Though I do not grow more varieties here, for the oriental poppies set an opulent tone and demand your attention whilst they are in flower, I have grown several in the past. At Home Farm I set ‘Perry’s White’, with its contrasting dark blotch, amongst gallica roses and inky bearded iris. I used the wood aster, Eurybia diviricata to cover for them later. For a while I also grew ‘Patty’s Plum’ for its thunderous bruised grey-mauve flower though it was never a keeper and dwindled for me. Then there was Saffron’, with wide open flowers of pale tangerine.

Burned into the June green, I will be there as I was aged five this coming weekend to witness their awakening. Never dimmed, always welcome.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 12 June 2021

The first frost of the season came on the night the clocks reverted from summertime. On the still, bright morning that followed, it hung in the hollows, the first fingers of sunshine liberating plumes of mist. We walked down to where they were moving between the yellowed ash and buttery hornbeam to find the leaves falling wet with thaw. Autumn in fast forward now and glorious for it.

Walking back up the ditch to where I had feared the worst for the Gunnera, we found them still standing. Their huge rough leaves had bowed a little, but it was good to find they were still in one piece and that there was time to put them to bed whilst the foliage was intact.

I have a special relationship with these giants, which are splits from a plant I bought with my Saturday earnings, aged ten. The mother plant, which grew in the nearby combe, was a thing of pilgrimage and I would cycle there summer and winter to marvel at its transformation. It sat on a bank where a spring broke to form a little pond at the roadside. In the growing season the water would be all but invisible, dwarfed by the enormous splay of foliage. Broken by winter, a skeleton collapsed and rotting in the water, it struck a sinister mood and I loved it for that.

I wanted to have some really quite badly, to live through the giant’s rise and fall during a year and to grow myself a colony that, one day, I could get lost in. Our thin, acidic sand at the top of the hill was no place for it but, undeterred, I dug a pit and filled it with a plastic liner in readiness. It took a while to pluck up the courage to cycle there with a spade strapped to my bike and to walk up to a stranger’s front door to ask if I could buy some. I remember quite clearly offering the owner a ‘fiver’ and the surprise on his face (it must have been a good sum in the mid ‘70’s) as he said, “Yes. Help yourself !”. I have no recollection of wrestling a growing tip from the mud, but I do recall smiling all the way home with my hard-earned booty strapped to my bike.

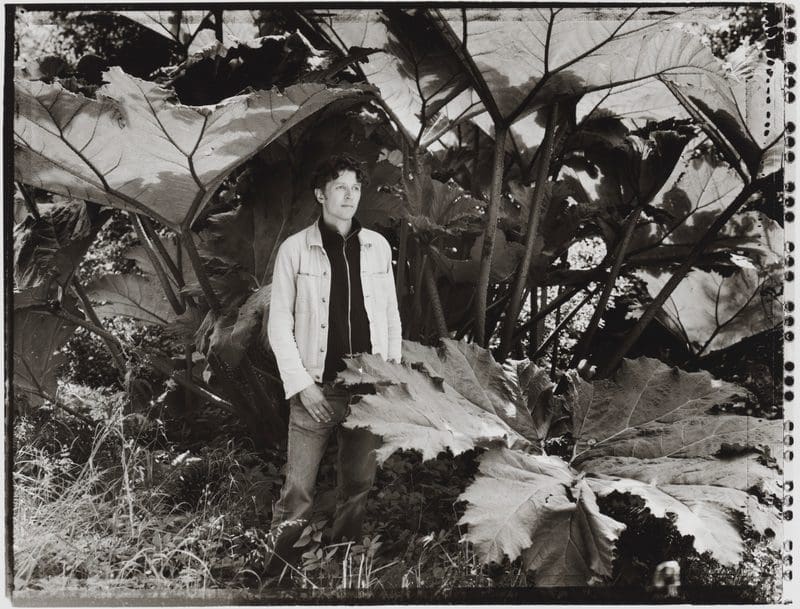

Needless to say, and despite my attentiveness with watering, it didn’t do well until I found it a place in the overflow of the cesspit. Beth Chatto’s advice to “Feed the beast” was my inspiration and, as Gunnera really needs its roots in a steady supply of water, the richness here was the answer. In the years after I left home it grew and it grew and it grew and became quite the focal point in the orchard. Many years later when the photographer, Tessa Traeger, asked me to choose a place that meant something to me for a portrait I asked to be photographed beneath it.

So, after moving here, I was presented with the perfect opportunity to be reunited and relive the drama, the life and death throes of the giant rhubarb. Our wet, oozing ditch and boot-sucking mud where the springs burst from the hillside have made it the perfect home. I have planted about ten offsets which, five years later, are beginning to provide some bulk, since they take a while to settle. A little shelter from the wind provided by the crack willow sees it do best where the plants sit outside the canopy. They grow half as well and rangily in the shadows. Although they should easily double in size with time, the colony is already a place I have dreamed about for some time. A scale change in every way. Somewhere you can walk into and get lost in, the giant parasols throwing a green light as you move amongst them. The prehistoric foliage rasping and textured above you.

Hailing from highlands in Brazil, Gunnera manicata is all but hardy, but it is safest to protect the hoary crowns in winter. Old plants can come through a winter without a cloak of shelter, but two years ago in our heaviest winter here I lost all the main crowns where the frost hung in the hollows. Folding the foliage over the crowns, like a thatch or multi-layered hat is usually sufficient, but until my plants grow strong, they are insulated first with a layer of hay. Cutting the foliage before it is frosted allows for the sturdiest construction and there are few things as satisfying as winter draws close than putting these wigwams together. Protecting the beast for a sure reward once the clocks change again and it stirs from slumber.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 November 2019

I have been away for work for just over a week, a week that has seen the buds on the plum orchard break into luminous clouds of flower. I was aware when we scheduled this time away that it would be a small torture knowing that this long-awaited moment was going on without me, but there is nothing like returning to change.

To add to the tension of being away, at the last minute my return plane was rerouted via Beijing for a sick passenger when we were half way across China. It was well after midnight when I pulled into the drive at home. There was a chill in the night air but there to greet me, pale and luminous at the bottom of the steps, were the poised chalices of Arum creticum. I had noted the slim green fingers and promise of flower as I’d left and the time I’d spent away was marked in their transformation.

Rolled back to open throats to the sky, the twist of their creamy sheaths would surely inspire a milliner. Fresh, primrose yellow with a darker, yolky spadix they sit well against the glossy foliage which has been good all winter, but will soon be gone as the energy is drained once the flower is pollinated. Where many arums attract flies with a foul or animal smell, Arum creticum has a sweet perfume that hangs gently in the air on a still, sunny spring day.

Arum creticum is a plant that has an exotic feeling about it, without making you fear for its hardiness. I have yet to see it in its native habitat in Greece, but have read that it is found in cool crevices in open, deciduous woodland. Though it is perfectly hardy here, rising early in a countermovement to flush fresh green leaf in autumn, it prefers a position where it can bask in winter sunshine and a leaf-mouldy soil that holds moisture in winter and dries out in summer once the plant is dormant.

I moved the rhizomes to Hillside a couple of years ago from a clump that we had growing in the studio garden in London at the base of a south-facing wall. They flowered well for the first couple of years, but my desire for privacy has rapidly seen this one-time hot spot become shadowy, as the limbs of Cornus ‘Gloria Birkett’ have reached up and out to dapple the garden. As the shade made itself felt, so the arums went into a holding pattern of leaf and no flower to let me know that, although in Greece life on the woodland floor might be tolerable, it was not so here where the intensity of spring light is so much less reliable.

I dug up the rhizomes just as the plants were going into dormancy and put them against an east-facing wall where they have all the light they need, but also, importantly, shelter from our prevailing westerlies. I’ve noticed that I have left some youngsters behind in London, for the rhizomes divide easily, but I will gather them up in the next couple of weeks and bring them to Somerset to extend my little colony.

Being one of the first parts of the planted garden you meet as you approach the house, the companions to the arum are also early risers. A fellow from the same country in Ferula communis ssp. glauca, a fellow to the fennel’s featheriness in the fern-leaved Paeonia tenuifolia and the early species wallflower Erysimum scoparium, a native of the Canary Islands. The simplicity and architecture of the arum sits well against the filigree foliage and the mutual break with winter could not make a better welcome.

Words: Dan Pearson/Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 March 2019

It has rained every day but one over the last fortnight. Not just a passing shower, but the whole day, like the ones you remember confining you to the house during the school holidays. The ground is wet, as saturated as it can be, and the stream has been rushing driftwood into dams, scouring the banks and rumbling stones into new places.

I have ventured carefully onto the beds just twice whilst we have been here over the Easter period to pull bittercress and winter-growing speedwells. They have seized the no-go zone and have made growth despite the cold. Hardy celandines have flushed the hedgerows with leaf, but they have not been showing their lacquered petals because the sun has stayed behind cloud. Elsewhere, there is half as much growth as this time last year and I find myself yearning for the chance to fill a jug with spring things, for the excitement of the new.

With the winter refusing to loosen its grip, the pickings have been slim, but this is compounded by the fact that this is a new garden. The tardy spring is a also a clear reminder that when you start from scratch, a garden is a commitment to waiting and though I know it will ease as soon as the weather warms, right now I am feeling the hunger.

I have started a list of early to bloom flowers that I’d like to see more of next year. The garden could take more pulmonarias in several places and in quantity for that early colour, and so that I can lace them with early bulbs. Right now, this is a garden without bulbs, because I like to feel settled for at least a year before introducing a layer that can complicate change if you need to make it early on. We have bulbs in the meadow banks that are slowly establishing, but their absence amongst the new life of the garden is stark. I want to see erythroniums where there will be a little shade, Ipheion where the sun can spring open their flowers and early Corydalis to make their way through the groundcovers as they mesh together.

Gladiolus tristis

Gladiolus tristis

Up by the house and alongside the barn where we are a couple of years ahead and have already started to introduce the bulb layer, I have planted Crocus speciosus, Nerine bowdenii and Amaryllis belladonna for the autumn, but right now and rising above them all at the other end of winter is Gladiolus tristis. This willowy South African is a week or so later this year, but miraculous enough in its emerging form to stave off my hunger. Awakening from summer dormancy in the autumn, their needle like leaves push through the receding growth of their neighbours to stand tall already through the dark months. Reading will tell you that they need a sheltered spot and yes, I have seen this winter green foliage damaged in a frost pocket, but they have stood unscathed by this year’s winter on our exposed slopes. Literature will also tell you that the Marsh Afrikaner is to be found in wetland areas and on banks above streams in high grassland in the wild, but here free-draining ground and full sun provide their favoured position.

The flowers, which unfold themselves like bony fingers from their slender glove of foliage, are delicately balanced on almost invisible stems. Their necks tilt upward to suspend the flowers as they develop and there is room between each, flushing later in April first green then a luminous primrose to cream as they age. Standing at almost three feet by this point the hooded blooms will catch the slightest breeze to sway, tall and elegantly. At Great Dixter, where I first saw it in the Sunk Garden, I imagine its night perfume would be caught on still air held by the surrounding buildings. Here on our breezy slopes, we have it by the path so that you can dip your nose to the flowers at twilight.

Staking the rangy limbs is necessary if they strain and topple for light, so I like to grow it hard in a bright, airy place to keep strength in the limbs. Staking it once it is grown is almost impossible, however, as its foliage is every bit as delicate as the reeds it resembles and will bend irreparably once it falters. A network of hazel twigs, inserted if you can remember in the autumn, will allow it to grow into position and not to distract from its finely drawn outline. One that in every move of its early awakening will help in staving off the hunger pains brought on by a reluctant spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 April 2018

The melancholy thistle (Cirsium heterophyllum) were a late arrival at our Chelsea Flower Show garden last year. We were moving slowly and surely into the last few days of planting up the garden and Peter Clay, our plant-meister at Crocus, rolled up with a car boot full. We were in the process of studding the wildflower turf with special moments, acid yellow Zizia aurea from North America, scarlet Tulipa sprengeri, white camassias, and marsh orchids collected from Peter’s own land, to name just a few. He said it was his custom, in the last few days of the Chelsea build, to do a trawl of some of the specialist nurseries just in case there was an undiscovered prize that the garden had been waiting for.

The melancholy thistle were just that, standing strong at that point and still in textured bud at about a foot high, but you could see they were set on taller things. I didn’t want the garden to be an all-singing, all-dancing place. I wanted people to imagine they were somewhere real, where there were still things to look forward to. So I planted them under our pollarded willow and, over the course of the show, they grew tall and provided a sense of potential with their spineless, silver-felted foliage and beautiful scalloped buds.

Cirsium heterophyllum (bottom right) in the Chatsworth Laurent Perrier Garden at the 2015 Chelsea Flower Show

Cirsium heterophyllum (bottom right) in the Chatsworth Laurent Perrier Garden at the 2015 Chelsea Flower Show

When the garden was dismantled I took one of the thistles as a memento. They had taken on a far greater significance during the course of the show, since I was standing amongst them when one of my most loved musicians complimented me on the garden and I invited her in to have a closer look. It was a chance happening which caught me completely by surprise and, out of nervousness, I talked far too much. Suddenly the bubble was burst, she had to leave, and I missed my chance to express my admiration. I felt foolish for perhaps having overwhelmed her and, as I pondered the thistles, a little sad that I had not simply let her look. These sorts of experiences are what gardens are made of and, back home, the memory of the meeting grew with the thistle and I haven’t been able to pass the plant this year without thinking of it.

“Despite the size and resonance of its shaving-brush flowers, I have no intention of introducing it into the garden…”

A fairly rare British native, Cirsium heterophyllum can be found in wet meadows and on river banks in the uplands of Scotland, Wales and Northern Britain. So I found it a special place that I thought it might like on a bank where we have spring seepage that keeps the ground moist. It spreads rhizomatously and my solitary plant has doubled its domain this year, and, so far, is holding its own amongst the meadow grasses. Despite the size and resonance of its shaving-brush flowers, I have no intention of introducing it into the garden, as I can tell that it would be mingling with, and then choking, its neighbours in no time. However, checked by company in the meadow, it is a fine addition, glowing like a magenta beacon for a month in June and July.

Cirsium heterophyllum in meadow grass on our damp bank

Cirsium heterophyllum in meadow grass on our damp bank

The flowers tilt ruefully to one side whilst maturing, and this is believed to be the origin of its common name. The ancient medical ‘Doctrine of Signatures’ states that plants resembling particular parts of the body can be used to treat ailments of those parts of the body. And so the thistle was was used to treat melancholy, as well as numerous respiratory ailments. In his Complete Herbal (1653) Nicholas Culpeper states, “…the decoction of the thistle in wine being drank, expels superfluous melancholy out of the body, and makes a man as merry as a cricket; …my opinion is, that it is the best remedy against all melancholy diseases that grows; they that please may use it.”

“…the decoction of the thistle in wine being drank, expels superfluous melancholy out of the body, and makes a man as merry as a cricket…”–Nicholas Culpeper, The Complete Herbal (1653)

I must admit to being more merry than melancholy that it has taken so quickly here, and I hope it will colonise the damp ground around it so that one day this part of the upper meadow will blaze. To help, I harvested a seed head picked just before the seeds were dispersed by the wind. I will sow it fresh, straight onto compost, and then top it with grit to keep off the slugs and ensure it doesn’t rot. With luck we may see seedlings this growing season. I will leave them undisturbed over winter and then prick them out to grow on next spring. I expect to be able to plant them out as the weather cools next September, for a bank full is sure to eclipse any lingering sadness.

Words: Dan Pearson/Chelsea photograph: Allan Pollok-Morris/Other photographs: Huw Morgan & Dan Pearson

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage