ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

Eleven years ago in this last weekend of October we arrived here on the hillside. It was a different place then. The house was damp, with a pink 1980’s bathroom, vinyl floral wallpaper and swirly carpets that hid a whole ecology of rot. It was a farmer’s house, so there were enough practical comforts. An old oil range, so we were warm once it was up and running and uPVC windows which kept out the weather, so we were happy. The house would be fine for a while, the real reason we were here lay beyond its walls and the land beckoned.

Grazed to the buildings by beef cattle, the trees had been cut back hard and the broken hedges were neatly flailed so as not to shade the grass. There were no concessions to anything but utility, but the views rolled on splendidly and without interruption. With the prospect also came exposure and, though we have become used to it now, when the wind blew that first winter, we woke to the house shuddering as if we were on the prow of a ship.

I knew immediately it would be wrong to plant out the view to provide shelter, but alongside the dream of finding this place came the long-term ambition to plant my own orchard. By the time the leaves were off the trees in the hedgerows, it was clear where it might be. Hunkered into the hill beyond the barns and stepping down the slopes in three parts to frame the landscape. I planted that first winter; a plum orchard on the higher ground where the earliest flowering trees would be least likely to catch the frost, West Country apples further down the slope and a group of pears to the west of the barns, where they would bask in sunshine and be afforded shelter from the easterlies.

The old adage goes, “You plant a pear for your grandchildren” and I’m pleased we moved quickly to get the trees in. A decade on and it is interesting to see what we have not had to wait that long to have learned. The pears that have done well in their huddle of shelter have grown into fine young trees, but their fruit is erratic, one year off and maybe another year on. On the fruiting years their habit of dropping all in one go over the course of a week when they are ripe has also proved problematic. The windfalls bruise and ripening is inconsistent in the branches, though the fruit still drops.

The pear trees we trained as espaliers on the south-facing walls of the kitchen garden have proven their worthiness in half the time. A half day applied training the limbs into position in combination with a late summer prune has given us reliable yields and an orderly backdrop. Pears that are ‘on display’ as it were and hanging neatly along branches to bask in sunshine also make better fruit. The fruit is restricted in number by the management of limbs where an unmanaged tree will, more often than not, be burdened with the flux of feast or famine. This year, we had a week of frost when the pears were flowering in April which saw all the blossom in the orchard trees lost, but we were able to fleece the trees on the protected walls.

We have four varieties, starting with ‘Beth’ in early August and they neatly hand over one to the other, ‘Beurré Hardy’, ‘Williams’ and the last and the best of them all, the delectable ‘Doyenné du Comice’. Doyenné (meaning ‘flavoured one’) was a mark of distinction when the first pear bearing the name, ‘Doyenné Blanc’ emerged in 1652. Several were to follow, but ‘Doyenné du Comice’ (1852) or the Comice Pear has been the most enduring. And with good reason, for the pear is of superlative flavour. In Joan Morgan’s excellent ‘The Book of Pears; The Definitive History and Guide to over 500 varieties’, she describes them thus: ‘Handsome, generous appearance with rich, luscious, very buttery, exquisitely textured, juicy pale cream flesh; sugary sweet yet intense lemony undertones, developing hints of vanilla and almonds’.

Of the four varieties on the kitchen garden wall ‘Doyenné du Comice’ is the lightest cropper, a four-tier cordon produces 15 to 20 fruit a year. You might think this would be enough, but they are so very good that, to mark our marriage five years ago, we planted two more cordons on the front of the house, where each new set of limbs marks time and increases our harvest.

During the last couple of weeks we have been watching keenly, but the last week of October, our moving-in week, seems to be the perfect time to harvest. Pears should be picked and ripened inside on a cool shelf for the best results. Cup the fruit gently in your hand, lift and gently twist a quarter turn. The stalk yields to the turn when it is ready and the fruit can be left in-situ if not. Make sure to check daily, because a fallen fruit will be nibbled and ruined overnight by mice. They also know of their charms, but do not wait for the fruit to fully ripen.

Jane Grigson writes beautifully about pears and, most notably that ‘the old legend that towards the end it may be necessary to get up at 3 a.m. to find absolute perfection is not a great exaggeration.’ Test for ripeness by applying gentle pressure at the neck with your thumb. If it is hard still, be patient, but as soon as the flesh begins to give, the fruit should be eaten, preferably with the skin so that the melt has some structure as contrast. Either alone or with cheese, a fine combination. A perfect fruit will be as good as a warm fig picked fresh off the tree in Greece. A delectable reward with the sun and summer goodness melting in your mouth as we slide into the dark weeks ahead.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 October 2021

It was exactly a year ago, in the first week of lockdown, that we committed to buying a polytunnel. That same week I placed a very late seed order primarily for tomatoes, but some chillis, aubergines and cucumbers came too and we started them off indoors at the end of March. This late start was further compounded by the delayed arrival of the polytunnel itself, so that the seedlings intended for it had to be held back by hardening them off in a makeshift structure of seed trays and pieces of glass, since the cold frames were full. Although they got a little leggy and had to be watched carefully to ensure their 9cm pots did not dry out, they escaped the very late frost we had on May 12th and were finally planted into their grow bags in the first week of June.

This year I sowed the tender veg a full month earlier in late February, starting them off on the airing rack above the kitchen range before moving them to a warm windowsill as soon as they started to germinate. We are always keen to try new varieties and this year, alongside our old favourites ‘Gardener’s Delight’ and ‘Sungold’, I made a selection from Real Seeds based on productivity and hardiness, and also a range from very earlies to lates to see if we can stretch the season and push the tomato harvest into early winter. ‘Amish Paste’ is a heavy-cropping, extra-large preserving tomato, which I am trying instead of ‘San Marzano’, ‘Feo di Rio Gordo’, a deeply ribbed Spanish beefsteak variety that is reputedly very early for its size, while two Ukrainian varieties, ‘Purple Ukraine’ and the peach-fleshed ‘Lotos’, have late seasons, the latter with a reputation as one of the latest-cropping tomatoes, with fruit still pickable in late December.

Last year’s aubergines suffered from not being planted out soon enough and failed in the frames so, determined to have a crop this year, we have three varieties on trial; ‘Black Beauty’, which has a reputation as the most reliable cropper in the UK climate, which it seemed to prove by being the first and most profligate to germinate and with the largest, heartiest seedlings. Germination of the other two varieties – ‘Tsakoniki’, a Greek heirloom variety and ‘Rotonda Bianca Sfumata di Rosa’, both from Thomas Etty – was a little patchier, but we have enough seedlings to have three plants of each and still have some left to give away to friends and neighbours.

As well as new chillis ‘Basque’ and ‘Chilhuacle Negro’ I have succeeded in germinating the seed of some tiny superheat red chilli bought at Kos market two summers ago and I’m trying sweet peppers for the first time (‘Kaibi Round No. 2’ and ‘Amanda Sweet Wax Pepper’, also from Real Seeds) as well as two varieties of melon (‘Petit Gris de Rennes’ and ‘Charentais’), which I’m hoping will get enough light and heat to provide us with something truly exotic in the fruit department this year. All of the above were sown in the last week of February and they are all, bar the melons, ready to be pricked out into larger pots this weekend.

The delay in planting out last year had a continuing knock-on effect, and the last of the tomatoes were harvested in late October so that we could remove the grow bags (which were were last year’s quick fix) to build four raised beds. These allowed us to build up the level and enrich the soil of the unimproved pasture on which the polytunnel is sited with well rotted manure. We intend to practice no dig with these beds and so the retaining edge will help to keep things tidy.

Although I had sown a variety of oriental greens, winter salads, chard, kale and soft herbs from the beginning of September and into October and November it soon became apparent that this was also too late since, by the time the raised beds were finished in early November, the days had shortened to the point that none of the seedlings would make no further growth before the end of the year. These plug plants sat rather reproachfully in the cold polytunnel until late January, when I finally planted them out as the days slowly started to lengthen. However, they have now been providing us with salad and greens for two weeks or more and have more parsley, coriander and dill than we know what to do with.

Despite the late start what has become immediately apparent is that, with well-timed sowing and transplanting, the polytunnel will allow us to close the ‘hungry gap’ of late winter and early spring. In addition to salad and oriental greens there has been a seamless handover from the waning kale and turnip greens in the kitchen garden to those that were sown in plugs in late November and have now taken up the baton. With this knowledge I am now planning two late summer sowings of winter greens and salads, turnips and beets for late July and late August to take us through the season. I started my first salad, beetroot and kohl rabi sowings off in the tunnel this year and they have responded well to the warmth and even light, but we are also planning to build a hotbed in the polytunnel this winter so that we can get even further ahead with early sowings and keep our most tender seedlings warm at night.

Alongside planning for future winter crops this is now the time to get moving outside. The broad beans that I sowed in modules in early March in the polytunnel have been hardened off for a couple of days this week, ready to be planted outside. And it is potato and onion weekend. The potatoes have been chitting in egg trays in the tool shed for the past three weeks or so and will be going into newly dug ground that we have enclosed around the polytunnel. This will free up more space in the kitchen garden to get a better successional rotation going, as well as allowing us to extend the range of vegetables we can grow, like Jerusalem artichokes which are very space hungry and freezer harvest crops like the ‘Cupidon’ beans of which we can eat any amount.

And I will also be pricking out the tomatoes, which is where this all started. Holding them carefully by their first cotyledons I will extricate their roots from one another, acutely aware of the time, energy and care that has got them this far. I will move slowly and carefully so that none are wasted. I will lower them into the soil of their own pots, give them a drink and then leave them to get on with it until it is their time to take the stage again.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 March 2021

With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

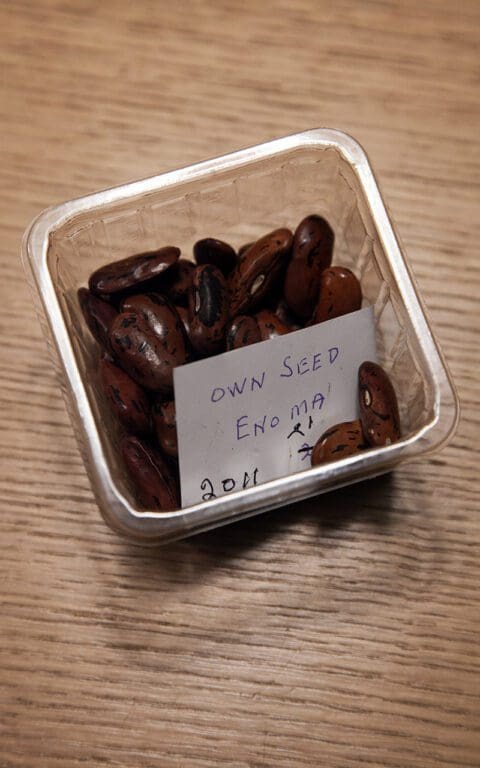

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

As I mentioned recently, one of our greatest challenges in the garden this year has been the new polytunnel. Having long discussed getting one, the prospect of being locked down in Somerset for the best part of the growing season meant that we were finally able to commit to the daily tending and watering requirements that weekending here meant we could never manage. Although the idea of this additional responsibility caused Dan’s mum, who was staying with us, some sleepless nights, the reality has been, in most ways, much easier than anticipated.

Our motivation for getting one was primarily to realise the unfulfilled desire to be more self-sufficient. We grow almost all of our own hardy fruit and vegetables, resorting to the greengrocers only for those things either grown under glass or imported. Although the novelty of being able to grow a whole range of tender fruit and vegetables was exciting, at the time we decided to go ahead there was a lockdown run on vegetable seeds, which meant that we weren’t able to source the everything we wanted to try. So we settled for what effectively became a trial of tomatoes. Having only grown very reliable outdoor varieties of tomato here previously, there has been much to learn and Dig Delve provides us with a means to record that learning for our future reference, as much as to share it with you.

Our first lesson was to discover that late March was very late to be sowing tomatoes under cover. We started the pots of seeds off on the airing rack above the range in the kitchen, where they were quick to germinate, before being moved to the cold frames.We were then lucky to have such good, warm weather in April, that the seedlings grew away strongly. However, because steel supplies were being diverted to make emergency hospital beds, every week the delivery date for the polytunnel would get pushed back by another fortnight. Very quickly the plants went from being just perfect to plant out to needing to be slowed down by moving them out of the frames.

Eventually, the polytunnel went up over a couple of days at the end of May and the tomatoes immediately went straight into grow bags. Having realised that there was not time to prepare and cultivate the section of pasture where the polytunnel was to be sited, we settled for organic grow bags and put down a membrane to suppress grass and weed growth. Next month we will take up the membrane and install a board edging to make two, low raised beds for cultivation over the winter and for the future. We have seen the effects of the late sowing and delayed planting out all through the growing season, with some varieties being slow to get going, and some just not cropping as heavily as we feel they ought to have done.

The next challenge, and one related directly to growing the plants in bags, was getting the watering regime right. When the plants are small their uptake of water is less predictable than when they are more mature and daily watering (twice daily in hot weather) is needed. This difficulty in judging when and how much to water in the early stages led to a combination of both under and over watering, which stressed the plants when they were around 90cm tall and just as they were starting to set their second trusses, which almost all aborted. None of them suffered from blossom end rot, though, which is also caused by erratic watering and so, with the benefit of hindsight, it became clear that things had also been exacerbated by the fact that I didn’t start with the potassium seaweed feed nearly soon enough. I now know that feeding should start as soon as the first truss has set and continue weekly through the whole growing season. The lateness in feeding also affected the ripening of some varieties, most notably the larger plum and beef tomatoes, which developed ‘greenback’, where the shoulders of the fruit fail to ripen, which is also caused by a lack of potash. Not all tomatoes are prone to this, however.

Although we had a heavy harvest of the first trusses in late July and early August, this meant that there was a significant gap in production during August, aggravated by the cold and cloudy weather that typified that month. It has only been since temperatures started to rise in early September that the ripening has started again. With some continued sun and the doors to the polytunnel kept closed night and day now, I am pretty confident that we will still have a good amount of ripe tomatoes to freeze and preserve for the winter.

Apart from those hurdles, the general maintenance of the plants has been very straightforward. The only puzzle was how to manage the plum tomato ‘Roma’, which I treated like all the other varieties, which indeterminate type. These are the cordon varieties that keep growing upwards and require pinching out and tying onto a support. Noting that it wasn’t responding as the others I did some Googling and discovered that it is a determinate or bush-forming variety, which should be allowed to grow freely. This may be what has been responsible for the very light crops with this variety.

We have had no pests to speak of and, when it did look as though there may be a risk of aphid proliferation, I quickly saw a polytunnel ecosystem establish itself with the arrival of ladybirds and hoverflies and, when the slugs arrived, I soon found that I was disturbing a frog and a toad while watering, as they sheltered in the damp protection of the grow bags.

Apart from the watering and feeding, all that has been required is a weekly session pinching out side shoots, tying the vines onto their canes, removing any yellowing foliage and giving the floor a sweep. In fact the thing that has taken the most time has been the harvesting, preparing and preserving of the fruits when the gluts, few as they have been so far, have come. As the autumn weather starts to turn from Indian summer heat to chill, I forsee only one more busy weekend of peeling, chopping and bottling ahead of me. That has been another learning experience which I will write more about another time.

Due to the seed shortage the varieties we were able to get hold of in March were limited to the most widely grown and popular, some of which, like ‘Gardener’s Delight’ I remember my grandfather growing, and which, with ‘Sungold’, Dan and I have been growing since our days in Peckham. They are popular because they are easy, hardy and productive, and also delicious. Others, such as the beef tomato, ‘Marmande’, Dan has grown for clients, while others were new to us and were chosen to have a range of colours and sizes to choose from. On our list for next year are ‘Costoluto Fiorentino’, ‘Purple Ukraine’ and hardy Russian variety ‘Moskvich’.

Gardener’s Delight

Sungold

Tumbling Tom Red

Tumbling Tom Yellow

Tigerella

Black Opal

Golden Sunrise

Marmande

San Marzano

Roma

Words and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 26 September 2020

This year our pride and joy (as well as provider of steep learning curve) has been the polytunnel. As soon as we decamped to Somerset before lockdown in mid-March, we started to discuss the pros and cons of finally biting the bullet and getting one, which we have discussed at length and then shelved on several occasions. The reason to defer was always the same. We weren’t here enough and, once a polytunnel is up and running, it simply can’t be left for days untended. Suddenly we were compelled to be at Hillside for the foreseeable future and, with the thought of more complete vegetable self-sufficiency firmly in the forefront of our minds, we decided to take the plunge.

Our dreams of a cornucopia of tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, chillis, cucumbers and melons haven’t been fully realised due to a shortage of seed and plug plants immediately after lockdown, and the fact that the polytunnel couldn’t be delivered until the end of May. So our initial plan for a tomato trial with three plants of ten varieties quickly increased to twelve plants of each and so this year, although we have three chilli varieties and two of cucumber, the polytunnel has been pretty much dominated by them. I will write at more length about the polytunnel at a later date, once I have some more experience under my belt, but suffice to say that growing tomatoes in grow bags has this year taught me the importance of a regular watering regimen, the effects of lack of ventilation and the dangers of not starting to apply tomato feed early or regularly enough. We lost almost all the second trusses and, due to the cool August, the third and fourth trusses are only now just starting to ripen. Everyone will be getting Green Tomato Chutney for Christmas this year.

Apart from firm favourites ‘Sungold’ and ‘Gardener’s Delight’ I was keen to trial some plum tomatoes and chose the best known and most reliable varieties, ‘San Marzano’ and ‘Roma’. These are the varieties that are almost invariably in any tin of tomatoes you might buy at the shops. They were surprisingly productive at first and the mini-glut in early August produced ten large jars of bottled whole and chopped tomatoes, as well as several litres of passata and ketchup. Although ripening is definitely slowing down now, somewhat surprisingly it is still the plum tomatoes that are providing the largest usable harvests. This I don’t mind, since I cook with tomatoes pretty often in winter and the idea of being able to use my own preserved ones and not shop-bought is very appealing.

Despite their productivity only the best plum tomatoes are good enough for bottling, so there are always plenty left over. These end up as passata or a simple tomato sauce (which I either bottle or freeze depending on available storage space) and in ketchups, salsas and chutneys. Quite often, however, they end up in our dinner and one of my daily challenges of recent weeks has been ‘What can you make with any combination of courgettes, tomatoes and runner beans ?’. After many nights of making things up as I went along I have started to run out of inspiration and so this week there has been much rifling of recipe books.

I very seldom present another cook’s recipes here, although my own are often tweaked and altered versions of dishes I have eaten or cooked from recipes in the past. However, when I came across this yesterday, it jumped out at me for the intriguing use of two of my main available ingredients in a previously completely unimagined form. What is in effect a tomato and bean pie is elevated in this recipe into a memorable dish of unctuous and exotic richness. Given the apparent humility of the primary ingredients I was unprepared for quite how delicious it is and feel that it is only right to share the original, untweaked, recipe with full credit to Maria Elia from whose excellent book of modern Greek cuisine, Smashing Plates, it is taken. As she says (and as I did myself) it is best to make the filling the day before you plan to assemble it so that the flavours can come together overnight. Of course, not everyone has access to vine-ripened plum tomatoes, so I weighed mine and they came to around 600 grams, equivalent to around two cans drained of their juice.

To balance the richness this would be good served with something fresh and bright such as a citrussy Greek cabbage and carrot coleslaw or a raw fennel, chicory, orange and watercress salad.

Serves 6-8 as a main, 8-12 as a small plate

100 ml olive oil

2 Spanish onions, halved and finely sliced

2 garlic cloves, finely chopped

2 tsp ground cinnamon

5 tbsp tomato purée

10 vine-ripened plum tomatoes, skinned and roughly chopped

500 g runner beans, stringed and cut into 4cm lengths

A pinch of sugar

1 bunch of dill (approx. 30 g), finely chopped, or 2 tbsp dried

1 packet of filo pastry (9 sheets)

100 g melted butter

100 g Medjool dates, stoned and finely sliced

250 g feta, crumbled

6 tbsp clear honey

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Heat the olive oil in a large, heavy-based pan over a low heat and sauté the onion until softened and sticky; this can take up to 20 minutes. Add the garlic, cinnamon and tomato purée and cook for a further 2 minutes. Add the tomatoes and their juices and cook over a medium heat for about 8 minutes, before adding the runner beans, sugar, dill, a pinch of sea salt and 150ml water.

Reduce the heat to a simmer, cover and cook the beans for about 40 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the beans are soft and the sauce is nice and thick. Check the seasoning and cool before assembling.

Preheat the oven to 180°C/gas mark 4. Unfold the pastry and cover with a damp cloth to prevent it from drying out. Brush a baking tray (approximately 30 x 20cm) with melted butter. Line the tin with a sheet of filo (cut to fit if too big), brush with butter and repeat until you have a three-layer thickness.

Spread half the tomato and bean mixture over the pastry, top with half each of the dates and feta. Sandwich another three layers of filo together with melted butter and place on top. Top with the remaining tomato mixture, dates and feta. Sandwich the remaining three filo sheets together as before and place on top.

Lightly score the top, cutting into diamonds. Brush with the remaining butter and splash with a little water. Cook for 35 – 45 minutes or until golden. Leave to cool slightly before serving, drizzling each portion with a little honey.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan | Recipe: Maria Elia

Published 12 September 2020

So this is my lunch. No, really, it is. Or I should say, was. Yesterday’s to be exact. Dan has been away for the past three days, his first trip of any length away from here since lockdown was eased, and suddenly I have found how much there is to do here when you are here alone. So time has been at a premium and yesterday the solution to not giving myself more to do than was manageable was to make my real life lunch the subject of today’s recipe.

The Kitchen Garden provides one of the main focusses of attention right now, with a tidal wave of produce rapidly gathering momentum, which needs harvesting, preparing and preserving. Every day there is a new round of beans, courgettes and tomatoes to harvest and these ingredients have featured in some way or another in most of our meals for the last couple of weeks.

The bush beans, ‘Cupidon’ and ‘Aquilon’ (the first of which we grew for the first time last year, the latter of which was new to us this year) have been providing a steady stream of fine green beans for around a month now. Although you do have to crouch to pick them it is very easy to de-top them while picking by pinching the stalk end of the bean, and it is possible to amass quite enough for dinner for two in a matter of seconds. We have probably blanched and frozen around 5kg over the past couple of weeks, and probably eaten the same amount. Although they are now on the wane and showing signs of exhaustion the first of the climbing beans are just forming, so we should have a perfect handover.

The bean recipe features the first of our polytunnel tomatoes, of which we are inordinately proud. We are still at the point where we are just keeping on top of the harvest and managing to eat them all, but plans are afoot to dry, bottle and puree the tomato deluge when it arrives. The simple tomato ‘sauce’ here can be made in bulk, flavoured with any herbs you like such as thyme or fennel, and kept in a container in the fridge or frozen to add to any number of simply cooked vegetables when you like.

The Italian way of serving summer vegetables in a sweet and sour agrodolce dressing or sauce is a favourite summer way with anything from cauliflower to mushrooms to fennel and courgette. The sharp, salty flavours are good on a hot day, but work equally well warm from the pan or at room temperature if the weather takes a colder turn.

The vinegar and honey dressing can be flavoured with anything you feel like. I might use fennel seed, bay leaf, marjoram, cumin or pink peppercorns depending on what is available. Some sliced anchovy, finely grated lemon zest and toasted pine nuts would work well too.

When time is of the essence it is best to keep things simple in the kitchen. No more ingredients or food preparation than is absolutely necessary. I use whole herbs and spices and keep cooking methods the same for multiple dishes so that things can be cooked together. This has the added benefit of reducing washing up. The method below is written to make both dishes at the same time, as I did today, so that they arrive at the table together.

You will need a large saucepan, a small saucepan, a colander, a small bowl and two medium mixing/serving bowls.

These dishes are perfectly filling alone, but can easily be augmented with a tin of sardines, a boiled egg, a slab of feta cheese or a piece of grilled halloumi.

Serves 2

Green beans & tomatoes

200g fine green beans

200g cherry tomatoes, mixed colours are good

1 large clove garlic

A small handful of small fresh basil leaves

2 tbsp olive oil

Salt

Zucchini in agrodolce

1 medium or 2 small courgettes, around 350g

5 tbsp white wine or cider vinegar

3 tbsp honey

1 fat clove of garlic

1 tbsp currants

2 tbsp extrafine capers

¼ tsp dried chili flakes

½ tsp whole coriander seed

12 black olives, stoned

A couple of stalks of flat leaved parsley, leaves removed

A small handful of small, whole mint leaves

Salt

Fill the large saucepan with water and bring to the boil.

Make the agrodolce. Put the vinegar and honey into the small saucepan with the coriander seed, chili flakes and clove of garlic which you have crushed under the blade of a knife. Put over a low heat until the honey has melted and the mixture is hot. Take off the heat and pour over the currants in a small bowl. Leave to soak.

Put the courgettes and beans into the pan of boiling water. Bring back to a simmer and cook with the lid on. Remove the beans after 10 minutes, refresh under cold water and drain. After a further 5 minutes cooking carefully remove the courgettes from the pan and leave to drain on a plate until warm enough to handle.

While the courgettes are cooling put the olive oil into the cleaned small pan and put it back on the heat. Roughly crush the second clove of garlic and fry in the hot oil until lightly browned. Tip in all of the tomatoes, put the lid on the pan and turn the heat up high. Cook hard for 2 to 3 minutes, shaking the pan frequently, until the tomatoes are breaking down, but still retain some shape. Take off the heat. Season with salt. Scatter over the mint and parsley.

While the tomatoes are cooking cut the courgettes into chunky pieces and put into one of the mixing/serving bowls. Pour over the agrodolce mixture while the courgettes are still hot, add the capers and olives and mix gently so that all the pieces are coated. Leave to stand while you finish the beans.

Put the green beans into the other serving bowl and pour the still warm tomato sauce over them. Mix gently to combine. Pour over a little more olive oil if you like. Scatter over the basil leaves.

Recipes, words and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 August 2020

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage