The Thalictrum ‘Elin’ are as spectacular as they ever will be, topped out at what must be almost ten feet in height and clouding a myriad of tiny flower. They are in their second year now and have been good from the day they broke their winter dormancy. Last year they sent up just a couple of spires each but, with roots deep and a year behind them, they have powered a forest of lustrous growth. First, an early mound of feathery foliage of a glaucous, thunderous grey flushed with purple and bronze which, by the end of April, had reached its full expansion and was ready to charge the ascent of muscular vertical stems soaring towards the solstice. Slowing once they had reached their full height, the panicles broadened as the lateral limbs filled out with a million buds. The ascent was every bit as remarkable as the cloud of smoky violet flower. Arguably more so for the dramatic build and anticipation.

‘Elin’ march through the planting in the lower part of the garden to provide punctuation, and I am depending upon them now to stay standing. Last year, when their limbs were heavy with flower, a rain-laden wind toppled them like ninepins, so I staked them with a waist-height hoops in early May to prevent a repeat performance. In our deep, hearty soil with plenty of sunshine and no early competition around their crowns, there has been nothing to hold them back, so I have grown them hard and so far denied them extra water. I am hoping this will mean that they grow more strongly and that their companion sanguisorbas help them to stay true.

Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’

I have grown Thalictrum aquilegifolium for years, where it is reliable in both sun or shade. A basal clump of foliage – well named for its similarity to columbine – is an early presence in the spring garden and the flowers are sent up early, ahead of most other perennials, so that there is a clear storey between them and their foliage. The wiry stems support clusters of stamen-heavy flowers which, when they are out, resemble exotic plumage. In the true species, the flowers are an easy mauve, but ‘Black Stockings’ (main image with Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’ and Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’) punches the colour up, with dark-stained stems and buds the colour of unripe grapes that open into flowers that register strong violet-pink. I have the white form too, which is strangely rare in cultivation, but not impossible to get. My plants came from the Beth Chatto Nursery, but I will be saving seed, which is viable if sown fresh, and I’m hoping will come true as they are quite some distance in the garden from their cousins. Seedlings that aren’t true white will easily be spotted for they have the purple stain, when the white form is pale, apple green. I plan to have plenty to play with and want to see if they will take in some open ground under the crack willow, where I let the Galium odoratum loose after it misbehaved and took too well to the garden.

Thalictrum ‘Black Stockings’

Thalictrum ‘Black Stockings’

Until ‘Elin’ appeared on the scene relatively recently, Thalictrum rochebruneanum was the tallest and most dramatic of the tribe. I saw it first at Sissinghurst, where it towered with Cynara in the purple border. As a teenager I lusted after its rangy limbs, impossibly fine it seemed, and the suspense in the delicate flowers. It languished on our thin acidic ground in my parents’ garden, growing to half the height. I tried it again in the Peckham garden, but it hated the way our soil dried as the water table dropped in summer. However, I have grown it well in California where, with a little extra water and shade from the sun, it seeds freely to spring up spontaneously as ‘volunteer’ seedlings. I hope that it will do the same for me here. So far in year two, it has done well, certainly not as well as ‘Elin’ but, with three or four flowering stems per plant, which have enjoyed the light at the base where they have been planted amongst later-to-emerge persicaria.

Thalictrum rochebruneanum

Thalictrum rochebruneanum

Hailing from Japan, where they find a niche amongst other perennials that like a cool, retentive soil, they must be a spectacular sight to come upon. Where ‘Elin’ is all about quantity, the flowers forming a Milky Way when they come together, every flower of Thalictrum rochebruneanum is a jewel. Richly coloured like gemstones, held sparsely so that your eye is drawn to the individual, inviting you to spend some time to take in the space and the colour contrast of the inner parts of the flower. A cup of violet petals holds the gold provided by the pollen and projection of anther within.

Never getting everything completely as I want it to be, I see now that I need to bring a plant or two up closer to the path, so that I can take in the detail and enjoy looking up, for you have to, your neck craned. Being early days in this garden, I can only hope for a volunteer or two to take to this ground and let me know that I have finally found them a place they really want to be.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 June 2018

When I was a child we spent every summer holiday in Wales, staying with my maternal grandparents who lived near Gowerton, the gateway to the Gower peninsula. When the weather was good we would head straight to Horton beach after breakfast, with crab paste and ham sandwiches wrapped in foil, hard-boiled eggs, bags of crisps and a tin of Nana’s homemade Welsh Cakes and pre-buttered slices of Bara Brith to see us through the day.

My grandfather was a Baptist minister, so on Sundays the day started differently. Nana was up even earlier than usual, housecoat on and getting lunch (or dinner as we called it in those days) prepared before we all headed off to chapel. All of the vegetables came from the back garden, which was given over entirely to food; potatoes, runner beans, peas, broad beans, lettuces, onions, beetroot, carrots, parsnips, swedes, cabbages and, of course, leeks. A tiny greenhouse was full to bursting with tomatoes and cucumbers. At the front of the house, the long bed running down one side of the path was filled with Dadcu’s dahlias, tied to bamboo canes in regimented rows, a cacophony of colour in every shape available, like sweeties. On the other side of the path an assortment of exotics planted into the lawn, including a phormium, a bamboo and a pampas grass, provided me and my brother with a playtime jungle.

The chapel was just on the other side of the street so, as soon as the service was over, Nana would head back to the manse to get dinner on the table for Dadcu’s return. Although a full roast dinner was not unusual on these sweltering summer Sundays, the meal I remember most clearly, and which was my favourite, was cold boiled ham with minted new potatoes and broad beans in parsley sauce. I loved the combination of the cold, salty meat, buttery potatoes and creamy beans and would ensure I got a little of each on every forkful.

Thinking back to this garden now I realise that, although Dad also grew veg in our North London garden, it was Dadcu’s kitchen garden where I first really understood the connection between plant and plate. My brother and I would be sent out to help dig potatoes, getting a rush of excitement as the first pearly tubers were heaved from the rich, dark soil, scrabbling to grab them and put them in the bucket. Pulling carrots straight from the ground I would think of Peter Rabbit, although I was sure that, unlike Mr. McGregor, the Revd. Jones did not have a gun. And often I would sit on the back step with Nana and Mum easing broad beans from their pods, marvelling at their cushioned, fleecy protection and enjoying the plonking noise they made as they fell into a plastic bowl at our feet. I never questioned that what we ate at mealtimes had been grown just yards from the dining table, nor that there was work required to get it there. I think that even then those vegetables tasted better to me because they were so fresh and I had helped get them to table.

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Although I can’t profess to be as good a vegetable gardener as my grandfather, now that we have a kitchen garden of our own, I find it hard to buy anything other than lemons, melons or peaches from the local greengrocer in the summer. The feeling of being able to assemble a meal entirely from vegetables you have grown, harvested and prepared yourself has no equal. People say that vegetable gardening is hard work, and I agree, but I don’t understand why this is seen as a negative. The time, care and nurturing that goes into producing your own food gives you a connection to it that is as nourishing as the food itself. When you understand the hard work involved in growing, tending and harvesting you stop taking food for granted and get some perspective on how much food should really cost.

So, to get back to the broad beans. We have grown two varieties this year. An unnamed heritage variety with very decorative, dark pink flowers and green beans from a late autumn sowing, and a variety named ‘Karmazyn’, with white flowers and beautiful rose pink beans, which were sown in March. Surprisingly, the later sown ‘Karmazyn’ have been the quicker to mature. Earlier in the season, as it became apparent that the plants were starting to overtake their autumn-sown neighbours, I was concerned that we were going to have a major glut when both varieties came together, but it now appears we will have a good succession from pink to the green. Close by the artichokes are producing almost faster than we can eat them. ‘Bere’, the variety we grow, is spiny with little meat at the base of the leaves, but the hearts are a good size, sweet and strongly flavoured.

Due to their synchronised production in the garden it is no surprise that broad beans and artichokes are commonly cooked together, with a variety of recipes to be found in French, Italian, Greek, Turkish and other Middle Eastern cuisines. What is common to many of them is the generous use of lemon and fresh herbs. This recipe is very loosely based on an Elizabeth David recipe for Broad Beans with Egg & Lemon from Summer Cooking, which would appear to be of Greek origin. Here the boiled vegetables are dressed with a light, creamy, herb-flecked sauce. A more refined and delicate version of my dear Nana’s beans, although just as good with a couple of slices of cold, boiled ham.

Artichoke ‘Bere’

Artichoke ‘Bere’

INGREDIENTS

Artichokes, 4 small per person

Broad beans, I kg in their pods to yield about 250g

Zest and juice of 1 lemon (reserve 1 tablespoon of juice for the sauce)

Sauce

Butter, 25g

Garlic, a small clove, minced

Cornflour, 1 teaspoon

The yolk of a small egg, beaten

Single cream, 4 tablespoons

Tarragon or white wine vinegar, 1 teaspoon

Lemon juice, 1 tablespoon

Cooking water from the beans, about 200 ml

Fennel, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Dill, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Tarragon, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt

Serves 4

METHOD

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Cook the artichokes for 15-20 minutes until the point of a sharp knife can be easily inserted into the base. Drain the artichokes, run under a cold tap for a moment and then allow to drain and cool completely.

Put the lemon juice in a small bowl. Cut the stalks from the artichokes and gently remove and discard all of the leaves until you reach the choke. Carefully scrape out the choke with the edge of a teaspoon. Tidy the hearts with a sharp knife removing any tough green bits. Rinse in a bowl of water to remove any clinging choke hairs. Dip each heart into the lemon juice as you go and put to one side in a bowl.

Bring a fresh pan of water to the boil. Throw in the beans and cook until just done. Freshly picked ones take only 2 or 3 minutes, older beans will take a little longer and may need to be slipped from their tough outer skins after cooling. When cooked remove 200ml of the cooking water and keep to one side. Then drain the beans and immediately refresh in cold water. Drain and reserve.

To make the sauce, in a pan large enough to take the artichokes and beans, melt the knob of butter until foaming. Take off the heat, put in the garlic and swirl the pan around to cook it lightly and flavour the butter. Still off the heat put in the cornflour and stir well. Add the cream and stir again. Add the egg yolk and stir once more. Then add about 150ml of the reserved cooking water, the vinegar and lemon juice. Season with salt. Put the pan back on a low heat and stir continuously until the sauce starts to thicken. Taste to ensure the cornflour is well cooked and adjust the seasoning. The sauce should be glossy and the consistency of single cream. If it is too thick loosen with some of the reserved cooking water. Put in the chopped herbs and lemon zest and stir through. Put the artichokes and broad beans into the pan and stir gently but thoroughly to ensure that all of the vegetables are well coated with the sauce.

Transfer to a serving dish, and strew some more herbs and lemon zest over the top. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Good enough to eat simply on its own or on toast, this is also a perfect side dish for poached salmon or trout, and cold roast chicken.

You can use any combination of soft green herbs that you have available. Chervil is particularly good, as are parsley and mint. For a more substantial side dish a couple of handfuls of the tiniest, boiled new potatoes make a fine addition.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 June 2018

The last of the perennial skeletons have now been cut to the base to make way for the turn in the season. It is just in the nick of time. Where just a fortnight ago the newly cleared ground gave away no more than a hint of what had been there before, we now have the evidence that spring is finally here. Held tight and close still, the flushed rosettes of embryonic foliage are bursting with energy.

This new life is remarkable for its break with dormancy and so begins our morning routine of combing the border for change. Sometimes, in the case of the lipstick red shoots on the peonies, it is a moment that is arguably as good as what comes later. The colour is strong and meaty and welcome against the dark ground. Team their flaming shoots with ‘Brazen Hussy’ celandines, which are up early too and done by the time the peony foliage shades them out, and you have a moment that is worthy of the weeks we have waited for such activity.

There is also the excitement of the appearance of new things. The autumn-planted Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’ (main image) have speared the bare soil of the new garden with priapic vigour. We will be watching them closely for the first sign of lily beetle, which makes its appearance much earlier than expected with the first warmth of the sun. I always try and plant those bulbs that are prone to beetle attack close to the paths so that it is possible to pick them off without trampling into the beds.

Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy

Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy

Paeonia mlokosewitschii

Paeonia mlokosewitschii

Paeonia mascula

Paeonia mascula

The rhubarb are at their best too and showing us now the huge reserves that they have built and stored in their crowns. The leaves, flushed copper, puckered and ready to expand, the crimson stems just waiting to push them to the light and the warmth that will very soon be in the sun. The rhubarb was moved just eighteen months ago, the autumn before last, and though I should be leaving it to build another year before forcing, it is clear that it has the heft. A quarter of the crown has been covered so that we can enjoy some early spears.

It is also a time to check that everything has made it. Just a week ago the fickle agastache, which easily succumb to winter wet, were looking like they might have done just that, but this morning I could see they have mostly made it through. Embryonic clusters of shoots held tight to the old wood, blue-purple and intensified in colour, but clearly identifying the plant that is yet to come. The pigmentation in new foliage is richest this early in the year with coppers, purples, blacks, reds and pale citrus greens. In the case of the Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’, the inky new growth is almost its best moment. New life, concentrated and full of anticipation.

Rhubarb ‘Timperley Early’

Rhubarb ‘Timperley Early’

Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’

Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’

Other rosettes reveal an exponential increase, more than you can imagine might have been possible between autumn and now, but one that shows that the plants are happy. Coppery Zizia aurea doubled, if not trebled, in size from last year and angelicas erupting to let you know that they have got their roots down. This year, I can see it already, they mean business and in some cases will be sure to overwhelm their neighbours.

Understanding the rush of early season growth and the impact it can have on later-to-emerge neighbours is key to achieving balance when you are mingling plants. The late-season grasses for instance will see panicum smothered, if it is not teamed with neighbours that are also late risers – asters and rudbeckias – companions that will allow them the time to catch up. This early-season flush is wonderful for the way it marks the break with winter, but it can easily leave a hole when early energy is expended and there is still the bulk of the growing season to come. Although it feels far too soon to even be thinking about it, a late June cut-back of early geraniums and the Anthriscus sylvestris ‘Ravenswing’ will be sure to provide a second crop of foliage.

The shift, mapped in these fingers of new life, and the clues to the growing season ahead, is a gathering tide. One that, if we photographed the garden again next weekend, would reveal something altogether different. Although I have savoured it this year, it is good to feel that we have finally reached the end of winter. A new year awaits in the joy of observing.

Anthriscus sylvestris ‘Ravenswing’

Anthriscus sylvestris ‘Ravenswing’

Zizia aurea

Zizia aurea

Allium christophii

Allium christophii

Allium angulosum

Allium angulosum

Tulip ‘Apricot Impression’

Tulip ‘Apricot Impression’

Paeonia ‘Coral Charm’

Paeonia ‘Coral Charm’

Paeonia rockii

Paeonia rockii

Angelica sp.

Angelica sp.

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum

Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum

Patrinia scabiosifolia

Patrinia scabiosifolia

Aquilegia chrysantha ‘Yellow Queen’

Aquilegia chrysantha ‘Yellow Queen’

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora

Nerine bowdenii

Nerine bowdenii

Eryngium eburneum

Eryngium eburneum

Cirsium canum

Cirsium canum

Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldschleier’

Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldschleier’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 March 2018

The winter form of last season’s skeletons has been easily as interesting as the first summer in the new garden. Though their muted presence is not the thing you plan for first, it is an aspect that is worth considering for the ghosts that are left behind. Some, the daylilies for instance, leave nothing more than the space they took in their fleshy growth period, but those that endure are arguably as good as they were in life. Without the distraction of a growing season, its pull of colour and the steer of upkeep, you are free to look at the dead, left-behind forms anew. Blacks and browns, sepia, cinnamon and parchment whites are far from monochrome and their structures and seedheads are worth planning for in combination.

Snow flurries and rain laden winds began the topple in January, but the garden endured and weekly we have observed it falling away, shifting, dropping back and thinning. The vernonia, with their biscuit seedheads, stood tall amongst the pale spent verticals of panicum and I welcomed the repeat of the finely tapered Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ together with the bottle-brushes of Agastache ‘Blackadder’. The birds loved them too and some days the garden has been alive with activity with the foraging for seed and overwintering insects looking for shelter. The black stems of the veronicastrum were good amongst the molinia stems, but their seeds were stripped by mice early on. The grasses have been key for their foil, their pale colouring bright on dry days, warm in the wet, and their plumage acting as light catchers when the sun has broken through.

The clearance required to make way for the new season has been carefully judged. There comes a point, some time when the bulbs are showing you that new life is on its way, that the skeletons begin to feel tired. We have also had to pace ourselves, for it has taken five man days to work through the areas that were planted almost a year ago and, this time next year, it will take another three when the areas of the garden that were planted last autumn are grown up.

The lower bed before being cut back

The lower bed before being cut back

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

We made a start in early February, working from the high ground that drained most freely and sweeping round to the heavier low bed by the field in a second session a fortnight later. In just two weeks buds that had been thoroughly dormant were already showing at the base of the euphorbias and the first new shoots on the grasses signalled the shift and the need to move things forward.

Before we started, I waded into the beds and marked the plants that I knew I wanted to change, for there are always adjustments that need to be made in a new planting. The densely-flowered Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ will be exchanged for the more finely tapered L. virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’, while the Artemisia lactiflora ‘Elfenbein’ that read too strongly as a group once their pale flowers caught the eye were left standing so that I could find them again easily and redistribute them so that their presence is lighter this summer. The changes will be different every year, but it is good to have time in hand to make them whilst the plants are more or less dormant.

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

The feeling of working through and stripping away is always a mixed one. I would leave some plants standing for longer, indeed, I have with the liquorice and the fennel, but the spring clean is good. Underneath the tussocks of deschampsia we unearthed the nesting places of voles, which had already tunnelled out and made a winter feast of my inulas on the banks. We only found one, which scurried to safety and I was relieved to find that their damage hadn’t been greater. Last year when lifting the molinias from the stockbeds to split them in readiness for the new planting, I found them almost completely hollowed out, roots and crown all but gone under the protective thatch of winter cover. There are pros and cons to leaving the garden standing and, although I prefer to do so, it is a good feeling to see the clean sweep reveal the planting again in new nakedness. Tight clumps, indicating quite clearly now that they have broadened, how the combinations were set out on the spring solstice almost a year ago.

The dry, cut material was piled high on the compost heap where it will be topped by some of last year’s compost to help in rotting it back for the future. And at the end of the day, as light was dimming, we carefully raked between the plants so as not to disturb last year’s mulch. A couple of weeks later I combed through the beds again to winkle out any seedlings that we’d missed in the first pass. Dandelions already in evidence and ready to take hold in the crowns of the grasses and buttercups and nettles that been secretly travelling in shade under the cover of summer growth. The beds that were planted and mulched last year will only be topped up this year where they have been disturbed where I’ve made alterations. Hopefully growth will be sufficient to suppress all but the strongest of the interlopers. Although we are still waiting for the planting that went in during the autumn to show itself enough before mulching these new areas, it won’t be long now until the need to move will be upon us and the garden once again dictates the pace.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 February 2018

The hush and the breathing space that comes, now that the leaves are down and the grass has finally slowed, is palpable. In the mild spells between freezes I take this opportunity to square up the holding area by the barns. This is where one day I plan for a greenhouse, but for now it is where I propagate and look after the plants that are waiting for a home. The cold frames which reared the spring seedlings are now packed to the gunnels with plants that need protection from the lethal combination of winter wet and freeze. Auriculas and the Mediterranean herbs are kept on the dry side and the autumn seedlings and cuttings will make a surprising leap forward with this little extra shelter. Out in the open and hunkered together for protection are bulbs to go out in the spring, once I can see exactly where they need to be and that they are the correct varieties, as well as youngsters that are ready and waiting for areas that are not quite prepared in which to set them loose. This backlog is a perpetual conundrum, but I have a three-year rule so that the holding ground avoids becoming a corner of shame. If they cannot be found a place, they will be put out on the lane with a sign saying, “Please help yourself”. Very few are left unclaimed and I trust they find good and unplanned for new homes. One of the cold frames

One of the cold frames

Auriculas

Auriculas

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018 Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

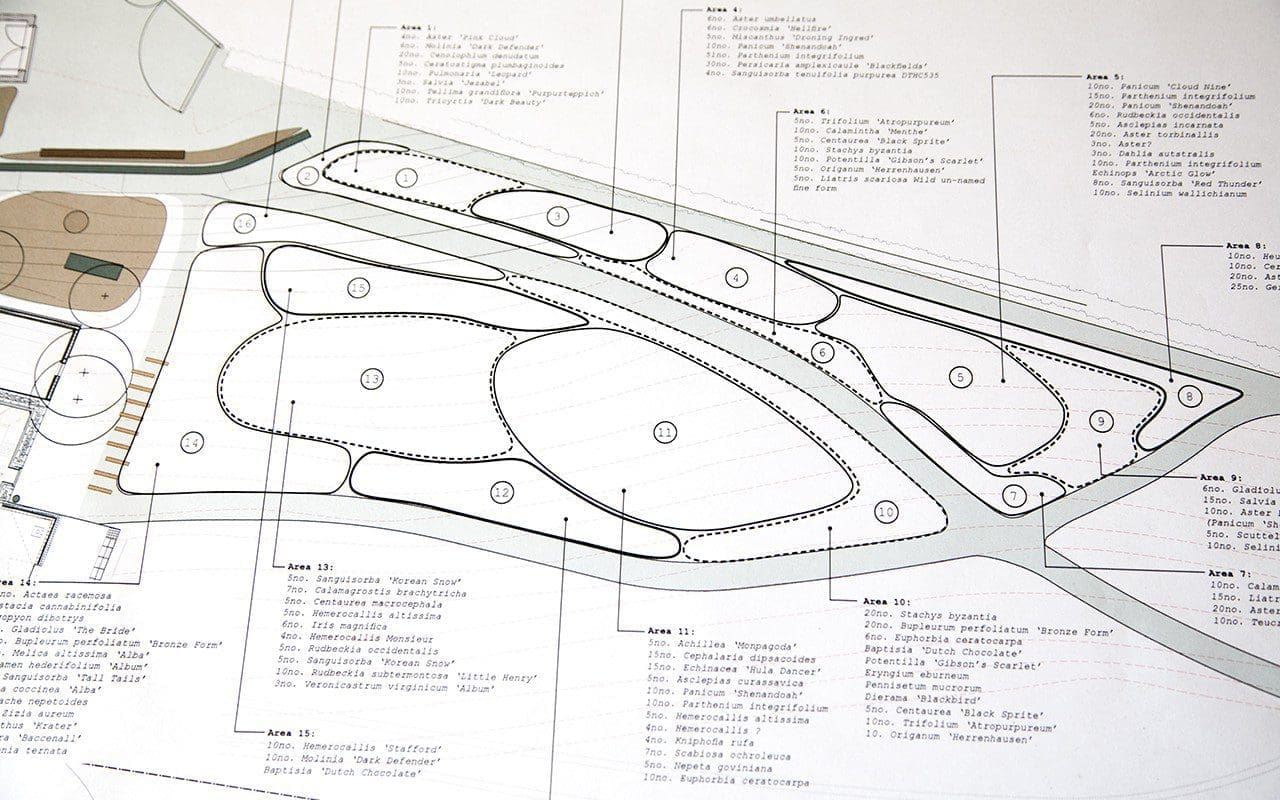

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

The self-sown sunflowers from the previous incarnation of the garden were the reminder that, just a year ago, we were growing the last of the vegetables here. I had allowed them the territory in the knowledge that this would be the end of their era, for they were in the bed that I now need back to complete the planting of the garden.

Felling them before they were finished was a relief, for suddenly, once they were gone, there was breathing space and the room to imagine the new planting. I’d also left the aster trial bed until the very last minute, eking out the weeks and then the days of its final fling. On the bright October day before we were due to lift, the bed was alive with honeybees, making the final selection of those that were to be kept for the garden that much more difficult. It was time to liberate the last of the stock beds, though, and to prepare the ground they occupied for a new planting.

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Planning what to keep and what to part with is difficult until the moment you make the first move. Over the last three years we have been keeping a close eye on the asters that will make it into the new planting. Keeping the best is the only option, for we do not have the space elsewhere and the overall composition is dependent upon every choice being right for the mood and the feeling that we are trying to create here. So gone are the Symphyotrichum ‘Little Carlow’ which, although a brilliant performer, needing no staking and being reliable and clump-forming, are altogether too dominant in volume and colour. Aster novae-angliae ‘Violetta’ is gone too. Despite my loving the richness of its colour, having got to know it in the trial bed I find it rather stiff and heavy and I want the asters here to dance and mingle and not weight the planting down.

The Aster turbinellus, for instance, has been retained for the space and the air between the flowers, as has Symphyotrichum ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ for its sprays of tiny, shell-pink flowers. I have also kept the late-flowering Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ for its modest habit and almost iridescent violet stars held on dark, wiry stems. I have always known that Aster umbellatus would feature in the planting, and so I lifted and split my three year old trial plant last autumn and divided it into six to bulk up this summer. There were many more that didn’t make the grade though, and I was torn about losing them, my self-discipline wavering at times. However, Jacky and Ian who help us in the garden eased my conscience by taking a number of the rejects home with them, and the space left behind, now that they are gone and I have finally committed, is ultimately more inspiring.

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

The reject asters

The reject asters

This is the second phase of rationalising the stock beds. In the spring, and to enable the preparation of the central bed, I split and divided the plants that I knew I would need more of come autumn, and lined these out in the top bed to bulk up; the lofty Hemerocallis altissima, brought with me from Peckham and prized for its delicate, night-scented flowers, the refined Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca, and the true form of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, originally divisions from plants in the Barn Garden at Home Farm which I planted in 1992.

I have not found a red day-lily I like more for its rustiness and elegance, and some of the ‘Stafford’ I have been supplied with more recently have notably less refined flowers and a brasher tone. I have planned for it to go amongst molinias so that the flowers are suspended amongst the grasses. Hemerocallis are easily divided and in the spring the stock plants were big enough to split into ten or so; the numbers I needed for their long-awaited integration into the planting. In readiness for setting out, and with the asters gone, we have now reduced the foliage of the daylilies by half, lifted them and then left them heeled in for ease of lifting and replanting.

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

The kniphofia and iris I had decided to keep went through the same process in March, and so the Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ and Iris magnifica were moved directly into their new positions where, just a week before, the sunflowers had towered. Similarly, the Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’ and Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’, which have both increased impressively, were lifted and moved into their new and final positions. This was in order to clear the old stock beds to make way for the autumn splits and keep the canvas as empty as possible so that I can see the space without unnecessary clutter when setting out.

The remaining trial rows – some Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield that I want in number and two white sanguisorba that will provide height and sparkle in the centre of the garden – were cut back to knee height, lifted and then split in text-book fashion with two border forks back to back to prise the clumps apart. Where the plants were not big enough I was careful not to be too greedy with my splits, dividing them into thirds or quarters at most.

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

Although October is the perfect month for planting, with warmth still in the ground to help in establishing new roots before winter, I have had to work around the trial bed of grasses and they now stand alone in the newly empty bed. Although I will be planting out pot-grown grasses next week, autumn is not a good time to lift and divide grasses as their roots tend to sit and not regenerate as they do with a spring split.

The plants I put in around the Milking Barn this time last year are already twice the size of the same plants I had to wait to put in where the ground wasn’t ready until the spring. I hope that the same will be true of this next round of planting, which will sweep the garden up to the east of the house and complete this long-awaited chapter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 October 2017

I am currently readying myself for the push required to complete the final round of planting in the new garden. The outer wrap went in at the end of March to provide the frame that will feather the garden into the landscape and, with this planting still standing as backdrop, I have been making notes to ensure that the segue into the remaining beds is seamless.

The growing season has revealed the rhythms and the plants that have worked, and the areas where tweaking is required. Whilst there is still colour and volume in the beds I want to be sure that I am making the right moves. The Gaura lindheimerei were only ever intended as a stopgap, providing dependable flower and shelter for slower growing plants. They have done just that, but at points over the summer their growth was too strong and their mood too dominant, going against much of the rest of the planting. This resulted in my cutting several to the base in July to give plants that were in danger of being swamped a chance, and so now they will all be marked for removal. Living fast and dying young is also the nature of the Knautia macedonica and they have also served well in this first growing season. However, their numbers will now be halved if not reduced by two-thirds so that the Molly-the-Witch (Paeonia mlokosewitschii) are given the space they need for this coming year and the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ the breathing room they require now that they have got themselves established.

Gaura lindheimerei

Gaura lindheimerei

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

I will also be removing all of the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ and replacing it with Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. I was so very sure when I had them in the stock beds that both would work in the planting but, once it was used in number, ‘Swirl’ was too dense and heavy with colour. The spires of ‘Dropmore Purple’ have air between them and this is what is needed for the frame of the garden not to be arresting on the eye and so that you can make the connection with softer landscape beyond.

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

As a gauzy link into the surroundings and as a means of blurring the boundary the sanguisorba have been very successful. I trialled a dozen or so in the stock beds to test the ones that would work best here. I have used Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ freely, moving them across the whole of the planting so their veil of tiny drumsticks acts like smoke or a base note. A small number of plants to provide cohesiveness in this outer wrap has been key so that your eye can travel and you only come upon the detail when you move along the paths or stumble upon it. Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, perhaps the best of the lot for its finely divided foliage, picked up where I broke the flow of the ‘Red Thunder’ and, where variation was needed, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ has proved to be tireless. Smattered pinpricks, bright mauve on close examination but thunderous and moody at distance, are right for the feeling I want to create and allow you to look through and beyond.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

The gauze has been broken by plants that draw attention by their colour being brighter or sharper or the flowers larger and allowing your eye to settle. Sanguisorba hakusanensis (raised from seed I brought back from the Tokachi Millennium Forest) with its sugary pink tassels and lush stands of Cirsium canum, pushing violet thistles way over our heads. The planting has been alive with bees all summer, the Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, now on its second round of flower after a July cutback, and the agastache only just dimmed after what must be over three months ablaze. Agastache ‘Blackadder’ is a plant I have grown in clients’ gardens before and found it to be short-lived. If mine fail to come through in the spring, I will replace them regardless of its intolerance to winter wet, as it is worth growing even if it proves to be annual here. Its deep, rich colour has been good from the moment it started flowering in May and, though I can tire of some plants that simply don’t rest, I have not done so here.

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

The lighter flashes of colour amongst the moodiness have been important, providing a lift and the key into the brighter palette in the plantings that will be going in closer to the house in a fortnight. More on that later, but a plant that will jump the path and deserves to do so is the Nepeta govaniana. I failed miserably with this yellow-flowered catmint in our garden in Peckham and all but forgot about it until I re-used it at Lowther Castle where it has thrived in the Cumbrian wet. It appears to like our West Country water too and, though drier here and planted on our bright south facing slopes, it has been a truimph this summer.

Nearly all the flowers in the planting here are chosen for their wilding quality and the airiness in the nepeta is good too, making it a fine companion. I have it with creamy Selinum wallichianum, which has taken August and particularly September by storm. It is also good with the Euphorbia wallichii below it, which has flowered almost constantly since April, the sprays dimming as they have aged, but never showing any signs of flagging.

Nepeta govaniana

Nepeta govaniana

Selinum wallichianum

Selinum wallichianum

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

I have rather fallen for the catmints in the last year and been very successful in increasing Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ from cuttings from my original stock plant. I plan to use the softness of this upright catmint with the Rosa glauca that step through the beds to provide another smoky foil.

Jumping the path and appearing again in the planting that will be going in in a fortnight are more of the Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’. True to its specific name, this pretty, white calamint seems happy to seed around in cool places and I have used it, as I have the Eurybia diviricata, as a pale and cohesive undercurrent. They weave their way through taller groupings to provide an understory of lightness, breathing spaces and bridges. Both of these are on the autumn order and will jump again into the new palette I have assembled to provide a connection between the two.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 October 2017

For the first three or four years here we grew row upon row of dahlias in the old vegetable garden. They soaked up the light in the first half of summer and flung it back again in a riot of colour later. We grew upwards of fifty, with rejects making way for new varieties from one year to the next to test the best and the most favoured. The dahlias were completely out of character with what I knew I wanted to do here but, like children in a sweetshop, we had the space to play and so we indulged.

Three years of experimentation left us gorged and satiated, but a handful made it through to become keepers. All singles, and delicate enough to be worked into the naturalism of the new planting, we kept Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’ for sheer stamina of performance, Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’, the most delicate of all, and the demurely nodding Dahlia australis. Proving to be perfectly hardy with a straw mulch as insurance against the cold they have made good garden perennials. The exception is a scarlet cactus dahlia that outshone the blaze of competition in the trial. Originally bought as ‘Hillcrest Royal’, but mis-supplied, we grew it in our old garden in Peckham and loved it enough to bring it with us and, then again, to keep it in the cutting garden. Unable to identify it correctly after many years of sleuthing we named it ‘Talfourd Red’ after the south London road we lived on and I cannot imagine an autumn now without its flaring fingers.

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

I do like a new plant, and getting to know Tithonia rotundifolia for the first time this year is enabling me to see how it might be used to inject some late summer heat into a planting. We already have a handful of favourites here that are tried and trusted and loved for their intensity of colour, which builds as the growing season wanes. In the case of the Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’, they are almost at their best sprawling and vibrant in the damp cooling days and allowed to climb into their neighbours. The seed originally came from the garden of Mien Ruys at least twenty years ago. I had gone with two friends on an inspirational trip to see what was happening in naturalistic gardens in Holland and Germany and we stopped to meet her in her wonderful garden. The seed was scattered on the pavement over which it was sprawling and a few found their way, with her consent, into my pocket.

This ‘Mahogany’ is not what you will get if you look for it in the seed catalogues. Indeed, it now seems to be unavailable apart from in the United States and ‘Mahogany Gleam’ is a different thing altogether. The leaves are a brighter more luminous green than usual and the flowers a jewel-like ruby red. I have been territorial ever since I started to grow it and winkle out any that come up with a darker leaf or paler flower. It self-seeds willingly every spring, letting you know when the soil is warm enough to sow and where the warmest parts of the vegetable garden are. The seedlings exhibit the same bright foliage so it is easy to weed out the occasional rogue, which might have reverted to the darker more typical green. We currently grow ‘Mahogany’ in the kitchen garden amongst the asparagus and use the leaves and flowers to garnish salad.

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Close by, and growing this year in two old stoneware water filters, is Tagetes patula. This wild form will grow up to three or four feet with a little support or something to lean on and flowers from June until it is frosted. The colour is absolutely pure and as vibrant and saturated a saffron yellow as you can find. It is easily germinated from seed under cover in spring and fast, so best to wait until mid-April to sow. I harvest my own seed and keep it apart from the dark, velvety Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (main image), which it will taint. Seedlings that have crossed will no longer have the deep richness that makes this latter plant so remarkable. I was disappointed to find this spring that the mice had eaten all the seed I’d left out in the tool shed and was expecting to have the first of many years without it. However, as luck would have it and quite out of the blue, they somehow found their way some distance into the new herb garden. Maybe it was mice doing me a favour with the plants I left standing in the kitchen garden last winter. Another lesson learned.

Tagetes patula

Tagetes patula

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

My father was never afraid of colour and always commented on the brilliance of Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’, which is the best, most brilliant red I have ever come across. Purer for the flowers being properly single, with elegant tear-shaped petals and thrown into relief against darkly zoned foliage. I bought a tray of plants from Covent Garden Market twenty five years ago for my Bonnington Square roof garden and have managed to keep them going ever since. Given how archetypal it is for a pot geranium I have no idea why it is not more freely available, but there are always a handful of cuttings in the frame which are for giving away to friends, who are given these precious things on the understanding they are part of keeping a good thing going, and that they are my insurance for any unexpected losses.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 September 2017

The new planting went in on the spring equinox, a week that saw the energy in the young plants shifting. Just seven days later the emerging fans of the hemerocallis were already splayed and flushed, and the signs were also there in the tightly-clasped crowns of the sanguisorba. The chosen few from my trial in the stock beds had to be split to make up the numbers I needed, but energy was on their side and, once in their new home, they seized life quickly to push new foliage.

We mulched the beds immediately after planting to keep the ground clean and to hold in the moisture whist the plants were establishing. Mulching saves so much time in weeding whilst a garden is young and there is more soil than knit of growth. This year I was also thankful because we went into five long weeks without rain. I watered just once, so that the roots would travel down in search of water, but once only so that they did not become reliant. The mulch held this moisture in the ground and the contrast to the old stock beds that went without has been is remarkable. Spring divisions that went without mulch have put on half as much growth and have needed twice as much water to get the same purchase. I can see the rigour of my Wisley training in this last paragraph, but good habits die as hard as bad ones.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

17 June 2017

17 June 2017

Since it rained three weeks ago, the growth has burgeoned. As the summer solstice approaches the dots of newly planted green that initially hugged the contours of our slopes have become three dimensional as they have reared up and away into early summer. I have been keeping close vigil as the new bedfellows have begun to show their form, noting the new combinations and rhythms in the planting. Information that I’d had to hold in my head while laying out the hundreds of dormant plants and which, to my relief, is beginning to play out as I’d imagined.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

16 June 2017

16 June 2017

Of course, there are gaps where I am waiting for plants that were not then available, and also where there were gaps in my thinking. There are combinations that I can see need another layer of interest, and places where the plants are already showing me where they prefer to be. The same plant thriving in the dip of a hollow, but not on a rise, or vice versa. Plants have a way of letting you know pretty quickly what they like. At the moment I am just observing and not reacting immediately because, as soon as the foliage touches, the community will begin to work as one, creating its own microclimate that will in turn provide influence and shelter. I lost my whole batch of Milium effusum ‘Aureum’, which I put down to the exposure on our south-facing slopes. However, most of them have managed to set seed, so I am hoping that next spring the seedlings will find their favoured positions to thrive in the shade of larger, more established perennials.

The wrap of weed-suppressing symphytum that I planted along the boundary fence is already knitting together, and I’m happy to have this buffer of evergreen foliage to help prevent the landscape from seeding in. However, a flotilla of dandelion seed sailed over the defence and are now germinating in the mulch. We saw them parachuting past one dry, breezy day in April as if seeking out this perfect seedbed. They are easy to weed before they get their taproot down and will be less of a problem this time next year when there will be the shade of foliage, but they will be a devil if they seed into the crowns of plants before they are established. A community of cover is what I am aiming for, so that the garden starts to work with me, and time spent protecting it now is time well spent.

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

The comfrey is planted in three drifts. Symphytum grandiflorum, S. ‘Hidcote Blue’ and S. g. ‘Sky Blue Pink’. The latter is new to me and I’m watching carefully that they aren’t too vigorous. I’ll have to keep an eye on the next ripple of plants that are feathered into the comfrey from deeper into the garden as the symphytum can also be an aggressive companion. The Sanguisorba hakusanensis should be able to hold their own, as they form a lush mound of foliage, and the Epilobium angustifolium ‘Album’ should be fine, punching through to take their own space. I’ll clear the young runners where the creep of the comfrey meets the gentler anemone and veronicastrum.

The ascendant plants were placed first when laying out and will form a skyline of towers through which the other layers wander. They are already standing tall and providing the planting with a sense of depth. Thalictrum ‘Elin’ is my height already, a smoky presence of foliage and stems picking up the grey in the young Rosa glauca and proving, so far, to not need staking. This is important, because our windy hillside provides its challenges on this front. Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ has also provided immediate impact, its limbs inky dark and the mauve of the flowers giving early colour and contrast to the clear, clean blue of the Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’. Next year the garden will have knitted together so that the contrasts will work against foliage or each other, but for now the eye naturally focuses not on the gappiness, but where things are beginning to show promise.

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

There have been a couple of surprises already, with a fortuitous mix up at the nursery reavealing a new combination I had not planned for with a drift of Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’ coming up as S. nemorosa ‘Amethyst’. I am very particular about my choices and I’d planned for ‘Indigo’ since growing it in the stockbeds, but the unexpected arrival of ‘Amethyst’ has, after my initial perplexity, been a delight. I’ve not grown it before, and I like its earliness in the planting and how it contrasts with the clear blue of the Iris sibirica with a little friction that makes the eye react more definitely than with the blue of ‘Indigo’. I like a little contrast to keep zest in a planting. The Euphorbia cornigera, with their acid green flowering bracts, are also great for this reason with the first magenta of the Geranium psilostemon.

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

As the last few plants that weren’t ready in the nursery become available, I’m wading back into the beds again to find the markers I left there when setting out so that I can trace my original thinking. I am pleased to have done this, because it is very easy to start to reshuffle, but the original thinking is where cohesiveness is to be found. Changes will come later, after I’ve had a summer to observe and see where the planting is lacking or needing another seasonal lift. I can already see the original perennial angelica has doubled in diameter, and I’ve added eight new seedlings which, if left, will be far too many so a few removals will be necessary comer the autumn. Patience will be the making of this coming growing season, followed by action once I can see my plans emerging.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 June 2017