ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

It has been the most wonderful spring. Cool and nicely drawn out and kind to the irises for being dry during their magnificent three week flurry.

The garden is coming into its third summer in the greater part and its second in the remainder. Time enough for perennial planting to mesh and to have settled into serious growth as opposed to establishment. The roots are down and with it there has been a tidal surge that has been expressed most graphically in the Ferula communis. Fergus Garrett gave me two pots of seedlings four years ago. The straight F. communis and its more slender variant, F. communis ssp. glauca. They were potted on into long-toms to encourage a good deep root and kept in the frame for a winter before being planted out as yearlings.

Two growing seasons putting their roots down saw their filigree mound of foliage ballooning over the winter. They are usefully winter-green, providing a counterpoint to most of the world being in dormancy and, being on the front foot, by spring they were the trigger that let us know that the sap was rising. You could feel the energy mustering at ground level. A clenched fist at first when you parted the foliage to see what was coming, but soon a racing limb which soared skyward before branching and flowering against blue like an acid yellow firework. They have been quite the proclamation. One of optimism and joy and a garden that is finally coming together.

Ferula communis ssp. glauca

In the perennial garden where the outer planting is now coming into its third growing season, I can see how things are playing out. The giants in the mix, in this case Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ and Thalictrum ‘Elin’, have already muscled out anything that does not have the stamina for competition. I moved the asters that were showing me they didn’t like it out to the edges and replaced the gaps with shade-loving Cimicifuga rubifolia ‘Blickfang’, which were sent from Hessenhof Nursery in Holland. I like responding when a planting tells you it needs change and the thought of using the tall growing plants in our exposed, brightly lit site to shelter those that naturally prefer the cool ground. We could probably not have got away with this in the first year without the cover to prevent the cimicifuga from burning.

The iris here in the perennial garden are selected for their spearing foliage and refined form of flower. Iris fulva, the copper iris, is shown to best effect amongst bright Zizia aurea, and Iris orientalis from Turkey towering architecturally above their companions whilst the planting around them is still low. Early spears are one of the aspects I enjoy most in the early garden and Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ have been as strong and definite as you could ever wish a plant to be. In colour they have taken over neatly from the camassia,which were introduced this year. I like to wait a year or so before introducing bulbs so that I know where change might occur and can be sure they have the space to establish unhindered. I’ve learned though that camassia that are prone to seeding do not make good bedfellows in open ground, for they are profligate. Camassia leitchlinii ssp. suksdorfii ‘Electra’ is reputedly sterile and finishes just as the iris come into flower. Self-seeders have proven to be problematic on our rich ground so, when I am in doubt, I deadhead and leave a sample to see how seeding plays out.

This is exactly how I will manage the Allium atropurpureum, which are now worked into the planting in the middle of the garden. We planted fifty bulbs last autumn in the gaps between the Digitalis ferruginea. They have been wonderful for enlivening this area early in the season with the promise of leaf and bud and now height amongst the acid green euphorbia.

With summer firmly here but fresh still in its infancy, it is the moment of the euphorbias and they are mounding luminously throughout the planting. Standing back and looking down on the garden from The Tump, they remind me of my first sighting of the giant fennels in the Golan Heights when I was studying at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens in the mid-eighties. It was forbidden territory, the minefields floriferous for being completely inaccessible. As far as you could see there was a march of giant fennel with euphorbia and searing red anemone at their feet. Perhaps this memory was etched into my mind when I planned for spring and early summer here, for I find myself looking on and seeing the similarities. Euphorbia cornigera with its dark red stems high up in the garden, E. wallichiii with its weight and volume to the lower slopes where the ground lies damper and in the high, dry centre the Euphorbia x ceratocarpa nestle the black alliums. Scarlet Papaver ‘Beauty of Livermere’ dot and brighten.

As I look out of the window to the first proper rain we have had in quite some time, I can see the plants exhaling. The greens are brighter – if that were possible – the garden plumper already and readying to push again. There is promise and it is amplified.

Iris orientalis

Iris fulva and Zizia aurea

Iris fulva and Zizia aurea Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ Papaver orientalis ‘Beauty of Livermere’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Papaver orientalis ‘Beauty of Livermere’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Allium atropurpureum with Euphorbia x ceratocarpa

It has been an extraordinary run. Day after day, it seems, of clear sky and sunlight. I have been up early at five, before the sun has broken over the hill, to catch the awakening. Armed with tea, if I have been patient enough to make myself one before venturing out, my walk takes me to the saddle which rolls over into the garden between our little barn and the house. From here, with the house behind me and the garden beyond, I can take it all in before beginning my circuit of inspection. It is impossible to look at everything, as there are daily changes and you need to be here every day to witness them, but I like to try to complete one lap before the light fingers its way over the hedge. Silently, one shaft at a time, catching the tallest plants first, illuminating clouds of thalictrum and making spears of digitalis surrounded in deep shadow. It is spellbinding. You have to stop for a moment before the light floods in completely as, when you do, you are absolutely there, held in these precious few minutes of perfection.

Now that the planting is ‘finished’, the experience of being in the garden is altogether different. Exactly a year ago the two lower beds were just a few months old and they held our full attention in their infancy. The delight in the new eclipsed all else as the ground started to become what we wanted it to be and not what we had been waiting for during the endless churn of construction. We saw beyond the emptiness of the centre of the garden, which was still waiting to be planted in the autumn. The ideas for this remaining area were still forming, but this year, for the first time, we have something that is beginning to feel complete.

Looking down the central path from the saddle

Looking down the central path from the saddle

The view from the barn verandah

The view from the barn verandah

Of course, a garden is never complete. One of the joys of making and tending one is in the process of working towards a vision, but today, and despite the fact that I am already planning adjustments, I am very happy with where we are. The paths lead through growth to both sides where last year one side gave way to naked ground, and the planting spans the entire canvas provided by the beds. You can feel the volume and the shift in the daily change all around you. It has suddenly become an immersive experience.

An architect I am collaborating with came to see the garden recently and asked immediately, and in analytical fashion, if there was a system to the apparent informality. It was good to have to explain myself and, in doing so without the headset of my detailed, daily inspection, I could express the thinking quite clearly. Working from the outside in was the appropriate place to start, as the past six years has all been about understanding how we sit in the surrounding landscape. So the outer orbit of the cultivated garden has links to the beyond. The Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ on the perimeter skip and jump to join the froth of meadowsweet that has foamed this last fortnight along the descent of the ditch. They form a frayed edge to the garden, rather than the line and division created by a hedge, so that there is flow for the eye between the two worlds. From the outside the willows screen and filter the complexity and colour of the planting on the inside. From within the garden they also connect texturally to the old crack willow, our largest tree, on the far side of the ditch.

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

This first outer ripple of the garden is modulated. It is calm and delicate due to the undercurrent of the Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’, but strong in its simplicity. From a distance colours are smoky mauves, deep pinks and recessive blues, although closer up it is enlivened by the shock of lime green euphorbia, and magenta Geranium psilostemon and Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. Ascending plants such as thalictrum, eupatorium and, later, vernonia, rise tall through the grasses so that the drop of the land is compensated for. These key plants, the ones your eye goes to for their structure, are pulled together by a veil of sanguisorba which allows any strong colour that bolts through their gauzy thimbles to be tempered. Overall the texture of the planting is fine and semi-transparent, so as to blend with the texture of the meadows beyond.

The new planting, the inner ripple that comes closer but not quite up to the house, is the area that was planted last autumn. This is altogether more complex, with stronger, brighter colour so that your eye is held close before being allowed to drift out over the softer colour below. The plants are also more ‘ornamental’ – the outer ripple being their buffer and the house close-by their sanctuary. A little grove of Paeonia delavayi forms an informal gateway as you drop from the saddle onto the central path while, further down the slope a Heptacodium miconioides will eventually form an arch over the steps down to the verandah, where the old hollies stand close by the barn. In time I am hoping this area will benefit from the shade and will one day allow me to plant the things I miss here that like the cool. The black mulberry, planted in the upper stockbeds when we first arrived here, has retained its original position, and is now casting shade of its own. Enough for a pool of early pulmonaria and Tellima grandiflora ‘Purpurteppich’, the best and far better than the ‘Purpurea’ selection. It too has deep, coppery leaves, but the darkness runs up the stems to set off the lime-green bells.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

The newly planted central area

The newly planted central area

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Eryngium eburneum

Eryngium eburneum

There is little shade anywhere else and the higher up the site you go the drier it gets as the soil gets thinner. This is reflected in a palette of silvers and reds with plants that are adapted to the drier conditions. I am having to make shade here with tall perennials such as Aster umbellatus so that the Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which run through the upper bed, do not scorch. Where the soil gets deeper again at the intersection of paths, a stand of Panicum virgatum ’Cloud Nine’ screens this strong colour so it can segue into the violets, purples and blues in the beds below. I have picked up the reds much further down into the garden with fiery Lilium pardalinum. They didn’t flower last year and have not grown as tall as they did in the shelter of our Peckham garden, but standing at shoulder height, they still pack the punch I need.

The central bed, and my favourite at the moment, is detailed more intensely, with finer-leaved plants and elegant spearing forms that rise up vertically so that your eye moves between them easily. Again a lime green undercurrent of Euphorbia ceratocarpa provides a pillowing link throughout and a constant from which the verticals emerge as individuals. Flowering perennials are predominantly white, yellow and brown, with a link made to the hot colours of the upper bed with an undercurrent of pulsating red Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. Though just in their first summer, the Eryngium agavifolium and Eryngium eburneum are already providing the architecture, while the tan spires of Digitalis ferruginea, although short-lived, are reliable in their uprightness.

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

It has been good to have had the pause between planting up the outer beds in spring last year, before planting the central and upper areas in the autumn. We are now seeing the whole garden for the first time as well as the softness and bulk of last year’s planting against the refinement and intensity of the new inner section. Constant looking and responding to how things are doing here is helping this new area to sit, and for it to express its rhythms and moments of surprise.

I am taking note with a critical eye. Will Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ have a stay of execution now that it is protected in the middle of the bed ? Last year, planted by the path, it toppled and split in the slightest wind. Where are the Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Henry Eilers’ and, if they have failed, how will I get them in again next year when everything will be so much bigger ? Have I put too many plants together that come too early ? Too much Cenolophium denudatum, perhaps ? How can this be remedied ? Later flowering asters and perhaps grasses where I need some later gauziness. Will the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri grow strongly enough to provide a highlight above the cenolophium and, if not, where should I put them instead ? The season will soon tell me. The looking and the questioning keep things moving and ensure that the garden will never be complete.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 July 2018

I have recently returned from the opening of one of my biggest projects to date and feel the need to tell the story, as it is remarkable for its scale and farsightedness. Mr. Ma, our client and the visionary behind the forty-five acre development, started the journey over fifteen years ago. A dam was about to be built near his hometown in Jiangxi province south-west of Shanghai, and with its construction came the loss of the valley’s ancient camphor trees and Ming and Qing dynasty settlements of merchants’ houses. By the time I came into the story, and indeed it was the reason that I did, Mr. Ma had moved over ten thousand camphor trees to their new home in Shanghai.

Their journey was an extraordinary one. Some are believed to be almost two thousand years old and were so big that they had to be transported the 600 kilometres on army tanks. Bridges had to be made to get them across rivers, and tunnels excavated so that the cargo could pass. The trees were planted in a nursery on the outskirts of Shanghai, very close to a site which Mr. Ma had secured for a new development. Here a series of old warehouses were also repurposed for storage of the merchants’ houses which had been dismantled brick by brick and painstakingly repaired from the damage they had sustained during the Cultural Revolution.

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

I was introduced to Mr. Ma in 2012 by his friend and collaborator Han Feng, who had been tasked with helping to find a landscape designer to design the grounds. Han Feng and I had met at the Design Indaba in Cape Town earlier that year, where we had both been invited to speak and we met in London to talk about the project. I was inspired by the story of the rescued camphors and the idea of making them a new home, so we agreed to meet Mr. Ma when I was next in Japan at the Millennium Forest so that he could see my work there.

By this point Aman Resorts were collaborating with Mr. Ma to make a hotel and associated grounds and Kerry Hill Architects had worked up a masterplan for the site. Once I was on board we were tasked with detailing the whole site from the hotel to the streetscapes and a series of garden blueprints that would be used to furnish the gardens of 44 private villas; 26 antique merchant’s houses and 18 contemporary interpretations of them.

Mr. Ma was busily working away in the background with the government to secure a site of double the size that would become the backdrop to the development and allow the green lung of the camphor forest to reach out and take on this new ground. We were also tasked with designing the masterplan for the park, repurposing one of the agricultural canals to form a dividing lake and masterminding a wetland of considerable scale that would allow us to recycle and purify all the water that would be needed for the water features on the site. It was an extraordinary opportunity to create a public park that would also act as an environment to include wetland walks, meadows and a considerable acreage of woodland. A green heart for a new city that was quickly sweeping up and around the site, as the agricultural land was repurposed for the urban sprawl.

The site masterplan with Amanyangyun in the north and east and the forest park to the south west

Once it was complete we passed the park masterplan on to a local firm of landscape architects and concentrated our energies on the Amanyangyun site. However, it is gratifying now to know that the first phase – the lake, the wetland and the woodland that links the two sites – is already in place. In China things happen at an alarming pace and at a scale that we are unaccustomed to here, so in many ways it was good to pull back at this stage after securing the big ideas and concentrate on the detail of Mr. Ma’s site.

It took two years of careful collaboration with the architects, who were a delight to work with, clear in their thinking and open to the contrast of an informal overlay on the rigorous grid that defined their masterplan. My own journey, and that of the team that works with me in the studio, was put on a very steep learning curve. We had to learn fast about the very different cultures and way of doing things and we couldn’t have done that without the trust and thoughtfulness of our client who had put a team in place that helped to translate our ideas.

We were taken to see traditional Chinese gardens to understand their ethos, aesthetics and cultural importance. They were completely new to me, the precursor to the Japanese gardens which I have come to know well from my time spent there, but entirely different in their aesthetic. I was keen not to emulate the Chinese garden at the villas on the site, but it was important to understand the culture and how we could create something naturalistic that would sit comfortably in Shanghai and not feel out of place.

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

The same view this year

The same view this year

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

A different view of the same area after completion

A different view of the same area after completion

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

We soon found that, despite the vast range of Chinese plants that we grow and depend upon in the west, our choices on site were very limited. The Chinese garden depends upon a tiny palette compared to a western garden and thus the nursery trade there is very limited. Bamboos, from ground covering forms to timber bamboos, were not in short supply, neither were Nandina and Osmanthus, but our tree palette was narrow, with only two magnolias to choose from, M. grandiflora and the beautiful M. denudata. We had flowering Malus and plums, camellias and a number of auspicious fruits that we used close to the buildings. And there was no shortage of Chimonanthus so the building blocks were enough. It was what we did with them that made the difference.

Modern landscape design in China sees the groundcover layer packed densely with blocks of low level shrubs, such as azalea and Fatsia, but I wanted breathing space between a multi-stemmed layer of flowering trees that would sit under the canopy of the camphors and keep the space at human level feeling airy and light. We designed a number of groundcover mixes that mingled the staples together informally. Ophiopogon and Liatris sweeping through in a gently shifting constant with runs of Aspidistra in the deepest shade, which was replaced by the likes of Iris sibirica and Chasmanthium latifolium out in the glades, where we had made room for the light to break the overarching canopy.

Overview of the villa complex

Overview of the villa complex

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

We used a palette of Chinese natives and local wetland species to encourage wildlife, but pumped up the volume amongst the restful sweeps of green with lotus ponds that sat close to the buildings, coloured Nymphaea in water bowls on the terraces and highly scented Gardenias by doorways. The climate, though temperate, is just that bit warmer than London so we were able to include bananas in sheltered corners and Trachycarpus for the grandeur of architectural foliage.

After my initial dismay at the apparent limitations of choice, our palette soon felt big enough to do something interesting, but I did choose to import Hydrangea serrata from Japan, as we only had access to hortensia and H. quercifolia. By including the H. serrata we were able to ring the changes and make the development singular. Pink, white and ‘Macrobotrys’ Wisteria floribunda were also imported as we only had access to Wisteria sinensis, which is the shorter-flowered of the two species. These additions to the staples and the commitment to breathing spaces in the planting soon made the difference.

The main riverside entrance

The main riverside entrance

The hotel entrance

The hotel entrance

We honoured the Chinese traditions with an auspicious fruit tree by every door and trees and shrubs that represented welcome or well-being and were well known for this layer of storytelling in the landscape. Our plans were all vetted by a feng shui master before anything was built – and we had to make some changes, but most of the moves in geomancy are based on good common sense and the changes were few. I suspect we were lucky.

There are numerous tales to tell about how we got to the point that the hotel and the grounds of the first villas were finally opened this spring, but they finally are and behind the scenes work continues to complete the remaining parts of the site. Though the planting has been in a year at most, it is already beginning to pull the buildings together. You look up to see the camphor trees regenerating, the King tree in the main courtyard already assuming presence. It will be a time before their branches reach to touch and cast shade, but it is good to have been part of helping them to do so.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Dan Pearson and Sean Zhu

Published 2 June 2018

It has been an exciting autumn, and one that I have looked forward to and been planning towards for the past six years. It has taken this long to resolve the land around the house. First to feel the way of the place and then to be sure of the way it should be.

Though the buildings had charm, (and for five years we were happy to live amongst the swirly carpets and floral wallpapers of the last owner) the damp, the white PVC windows and the gradual dilapidation that comes from years of tacking things together, all meant that it was time for change. Last summer was spent living in a caravan up by the barns while the house was being renovated. We were sustained by the kitchen garden which had already been made, as it provided a ring-fenced sanctuary, a place to garden and a taste of the good life, whilst everything else was makeshift and dismantled.

This summer, alternating between swirling dust and boot-clinging mud, we made good the undoings of the previous year. Rubble piles from construction were re-used to make a new track to access the lower fields and the upheavals required to make this place work – landforming, changes in level, retaining walls and drainage, so much drainage – were smoothed to ease the place back into its setting.

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

Of course, it has not been easy. The steeply sloping land has meant that every move, even those made downhill, has been more effort and, after rain, the site was unworkable with machinery. We are fortunate that our exposed location means that wet soil dries out quickly and by August, after twelve weeks of digger work and detail, we had things as they should be. A new stock-proof fence – with gates to The Tump to the east, the sloping fields to the south and the orchard to the west – holds the grazing back. Within it, to the east of the house and on the site of the former trial garden, we have the beginnings of a new ornamental garden (main image). An appetising number of blank canvasses that run along a spine from east to west

The plateau of the kitchen garden to the west has been extended and between the troughs and the house is a place for a new herb garden. Sun-drenched and abutting the house, it is held by a wall at the back, which will bake for figs and cherries. The wall is breezeblock to maintain the agricultural aesthetic of the existing barns and, halfway along its length, I have poured a set of monumental steps in shuttered concrete. They needed to be big to balance the weight of the twin granite troughs and, from the top landing, you can now look down into the water and see the sky.

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

On the lower side of the new herb garden, continuing the bank that holds the kitchen garden, the landform sweeps down and into the field. Seeded at an optimum moment in early September, it has greened up already. Grasses were first to germinate, and there are early signs of plantain and other young cotyledons in the meadow mix that I am yet to identify. I have not been able to resist inserting a tiny number of the white form of Crocus tommasinianus on the brow of the bank in front of the house. There will be more to come next year as I hope to get them to seed down the slope where they will blink open in the early sunshine. I have also plugged the banks with trays of homegrown natives – field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and divisions of our native meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) – to speed up the process of colonisation so that these slopes are alive with life in the summer.

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Below the house, the landform divides to meet a little ha-ha that holds the renovated milking barn and a yard which will be its dedicated garden space. This barn is our new home studio and from where I am planning the new plantings. I have placed a third stone trough in this yard – aligned with those on the plateau above – with a solitary Prunus x yedoensis beside it for shade in the summer. There are pockets of soil for planting here but, beyond the two weeks the cherry has its moment of glory, I do not want your eye to stop. This is a place to look out and up and away.

That said, I have been busily emptying my holding ground of pot grown plants that have been waiting for a home, and some have gone in close to the milking barn to ground it; a Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ from the old garden in Peckham, a Paeonia rockii, a gift from Jane for my 50th, and the beginnings of their underplantings, including Bath asparagus and some favourite hellebores that I’ve had for twenty years or more. The spaces here are tiny and they will need to work hard so as not to compete with the view out, nor disappoint when you get up close on your way to the barn. The bank sweeps up to wrap the milking barn above and to the east and the planting with it, so that it is nestled in on both sides. Below the barn there is the contrast of open views out into the fields, so when inside I can keep a clear head from the window.

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

To help me see my new canvasses in the new ornamental garden clearly I have started dismantling the stock beds. The roses, which have been on trial for cutting, will be stripped out this winter and the best started again in a small cutting garden above the kitchen garden. I’ve also been moving the perennials that prefer relocation in the autumn. Jacky and Ian, who help in the garden, spent the best part of a day relocating the rhubarbs to the new herb garden. It is the third time I have moved them now (a typical number for most of my plants), but this will be the last. In our hearty soil, they have grown deep and strong and the excavations required to lift them left small craters.

The perennial peonies, which go into dormancy in October, also prefer an autumn move, as do the hellebores so that their roots are already established for an early start in the spring. They both had a firm grip and I had to lift them as close to the crowns as I dared so that they were manageable. The hellebores have been found a new home in a rare area of shade cast by a new medlar tree that I planted when the landscaping was being done. I rarely plant specimen trees, preferring to establish them from youngsters, but the indulgence of a handful, which included the cherry and a couple of Crataegus coccinea on the upper banks near the house, have helped immeasurably in grounding us in these early days. To enable a July planting these were all airpot grown specimens from Deepdale Trees which, as long as they are watered rigourously through the summer, establish extremely well. Usually right now is my preferred (and the ideal) time to plant anything woody.

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

It is such a good feeling to have been planting things I have raised from seed and cuttings for this very moment; a batch of seedlings grown on from my Malus transitoria to provide a little grove of shade in the new garden, rooted cuttings of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ to screen the new garden from the field below, and a strawberry grape (Vitis vinifera ‘Fragola’), a third generation cutting from the original given to me thirty years ago by Priscilla and Antonio Carluccio, is finally out of its pot and on the new breezeblock wall. Close to it I have a plant of the white fig (Ficus carica ‘White Marseilles’), a cutting from the tree at Lambeth Palace, where I am currently working on the landscaping around a new library and archive designed by Wright & Wright Architects. The cutting was brought from Rome by the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole, in 1556. In 2014 a cutting made the return journey to Pope Francis, a gift of the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. The tree reaches out from the palace wall in several directions to touch down a giant’s stride away. It is probably as big as our little house on the hill, and my cutting is full of promise. It is so very good, finally, to be making this start.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan, Dan Pearson & Jacky Mills

Marcin Rusak is a London-based Polish designer who explores themes of consumption, ephemerality, aging, decay and longevity in his work. For very personal reasons he has chosen to work with flowers in a range of different ways. I recently met him at his new studio where he talked to me about his history, his process and his creations.

Tell me how you arrived at this way of working with flowers.

It was quite an adventure for me to get into the Royal College of Art. It started with me studying European Studies, not liking it, doing interior design on the side and trying to get into art school in Poland. They didn’t accept me. So I tried the Design Academy Eindhoven, the conceptual design school, not knowing at all what conceptual design is. I was supposed to be there for four years, but after two I felt I wanted to experience more, and the way Dutch education works is they wipe your head clean and they inject their tools into you and after four years you’re only allowed to use those tools. So after years of study I knew that I wanted something more. I wanted freedom, so that’s where the RCA came into the picture.

At the RCA you’ve got this amazing ability to make mistakes all the time, and find your own thing. So I found my own thing through an accident again, because there was a brief to find an object that interests you, like from your past or wherever, just something that you like.

And so I found this cabinet that we had in my family house, which was from the 17th century. It’s a Dutch cabinet, and it’s carved in wood, and the whole sculptural decoration is inspired by nature and the seasons. So I just started investigating, ‘Why is it that I like it so much ?’. So the first natural step for me was to go and investigate nature and flowers – the subjects of the carvings – and I went to a flower market for the first time. And that’s where I started seeing all this waste. And because I was always interested in processes, I took the waste material and started doing everything I possibly could with it, to get somewhere, not really knowing where it was going. And that’s how I discovered printing with flowers.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

On your website there is a video of you making one of these textiles. What is the liquid you were spraying on the flowers ?

Vinegar. It helps to bring out the natural pigments in the flowers, and it also helps them to penetrate the silk. I also use special silks made specifically for digital printing, because they are treated with substances which react with ink, and although the flower pigments are not inks the silk reacts in the same way and the pigments become more light fast. When I first tried with normal silk the colour only lasted about a month. These pieces are about a year old and have not really faded that much, but they will fade eventually, although they will never completely disappear. I still have all the ones I made, as it is really hard to sell things that don’t last, but people have started to understand me better now, and they are prepared to buy the idea along with the object. Also recording the process of making the work becomes part of the work itself.

By the end of this project I went to my tutor, and I said, ‘You know what? It’s actually really funny that I’m doing these things with flowers now, because I have a history of 100 years of flower growing in my family.’

When I was born the business was closing down, so maybe about two or three years after I was born it closed. So until I was 26 and at the RCA I really had nothing to do with flowers.

I was raised in those abandoned glasshouses. That was my childhood playground. It was amazing. I still have this memory of the very dry warmth when you were in the glasshouses, but there was nothing else, just these pipes coming out from everywhere, and all these steel structures, but no flowers, no natural material. And then we moved when I was 10. My mum always loved flowers and she always wanted to do something with them, but she never did.

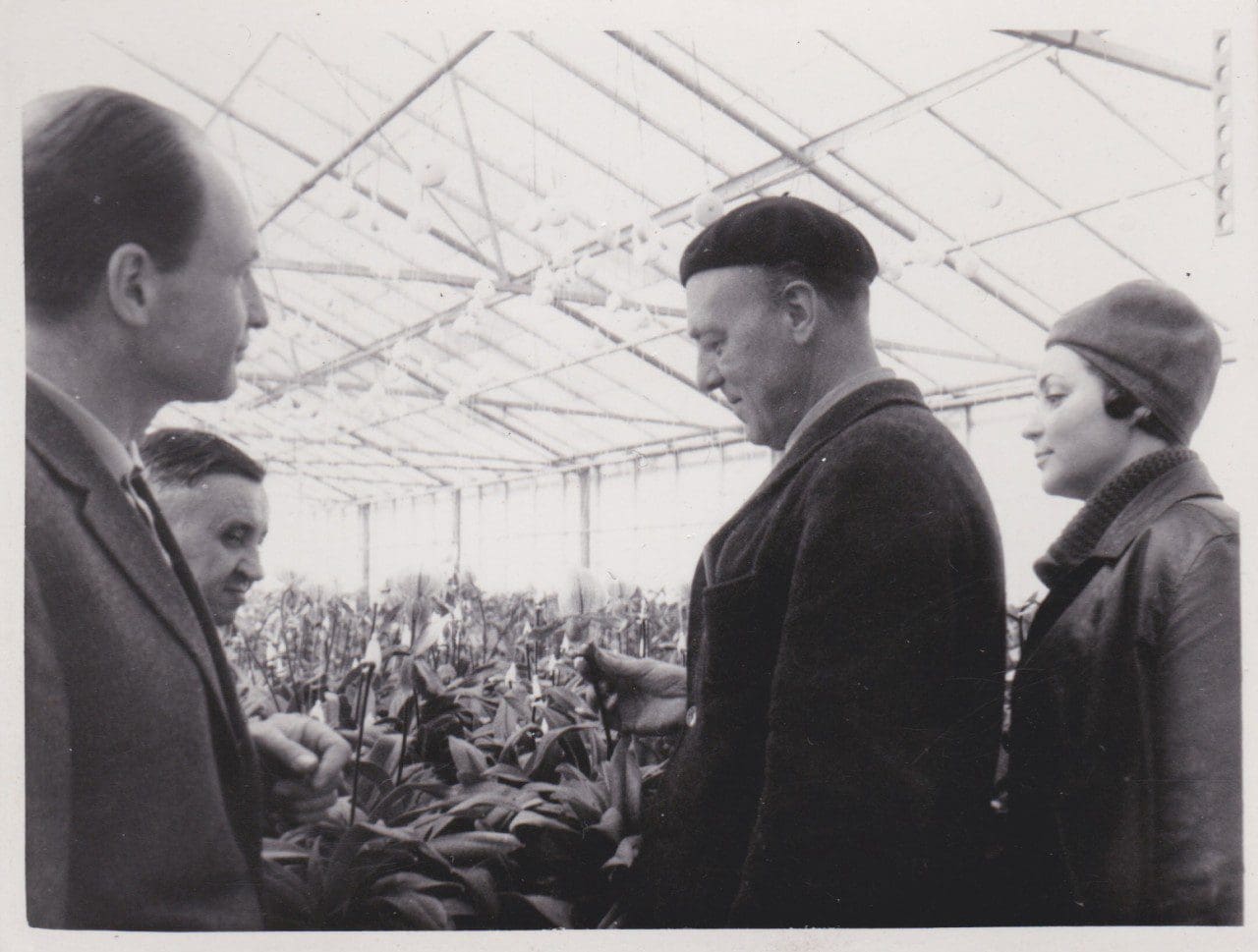

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So the flowers weren’t really in the family, they were in this amazing history we had, because my grandfather, and his father, for over a hundred years they were growing flowers. They also had flower stores, so they had a really big business, mostly growing orchids. And my grandfather was kind of a freako scientist, so he was really bad with people, but amazing with plants. So actually discovering this was a breakthrough for me, but it was also quite natural. Although I kill plants, or I use dead plants or I make objects that die !

But it made me think. I remember having this conversation at the RCA with one of the tutors, they asked, ‘Why are you doing this, actually ? It’s nice that its this textile that extends the life of already dead flowers by months or years, so that’s great, but what’s the interest ? Think about it. Why ?’

So then I started doing much more research work in the Netherlands and actually trying to understand why people manipulate flowers so much these days, and how flowers became a commodity, and how they are being sold in Tesco and grown in Kenya, and flown with planes and using water in places that don’t have water. All of the background of what people don’t know about commercial flower growing. And then I started explaining to people that it’s a bit like the food industry, that started to change 10 years ago, when we started realising how we source food and intensively farm it and so on and so on. So I established a connection with Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, right next to the massive flower market there. And I made a book about it.

So you got into the science of flowers through doing this book, which you hadn’t really thought about before ?

No completely not! Because, you know, like a lot of people I just didn’t know what the situation was with flowers being grown, because we don’t have to eat them, so we don’t really think of them in the same way that we think of food, because in a way, they are perceived as a luxury. So I started investigating it at the university and they helped me a lot. At the beginning they were very suspicious of what I was doing, because they work with a lot of big brands which pay a lot of money to get their research and I was going in there saying ‘Hey, can you tell me about this ?’ for nothing. But I established a nice connection and they let me see a few things and we started talking and I introduced to them to the idea of the flower monster that I wanted to do, which is basically combining everything we want from flowers today. From retailers, to growers and consumers, everyone wants flowers to be a certain way, either living longer or smelling better or being cheaper to ship. And in the end they should be this natural imperfection, and not manipulated so much, so for me it was interesting to think about how to put that all into one piece and start communicating it to people and make them aware.

So the idea was to create this flower that does it all. So if we play with the DNA, and if the industry keeps on going the way it is right now where we keep manipulating things, it is where we might end up. I first started talking to plant geneticists to try to understand about breeding and cross-breeding, because it is possible to cross-breed a lily with a bamboo and so on. So if you have a lily which has a stem with genes from a bamboo it can then stand on a strong stem and hold this whole creature up. But how do we get there physically ? How do we make it happen ? So we researched the plants that have the certain characteristics that we needed, so anthuriums are very light, so transportation would be easier, and bamboo for the stem, or orchids with their roots outside the plant which could transport nutrition, so the whole thing could live for months. So I started working with Dutch flower engineer Andreas Verheijen, who agreed to help me with the project, and we basically took the plant species, cut them up and put them together them as nature might. Then it was flown to London in a day. It was the weirdest thing I ever did.

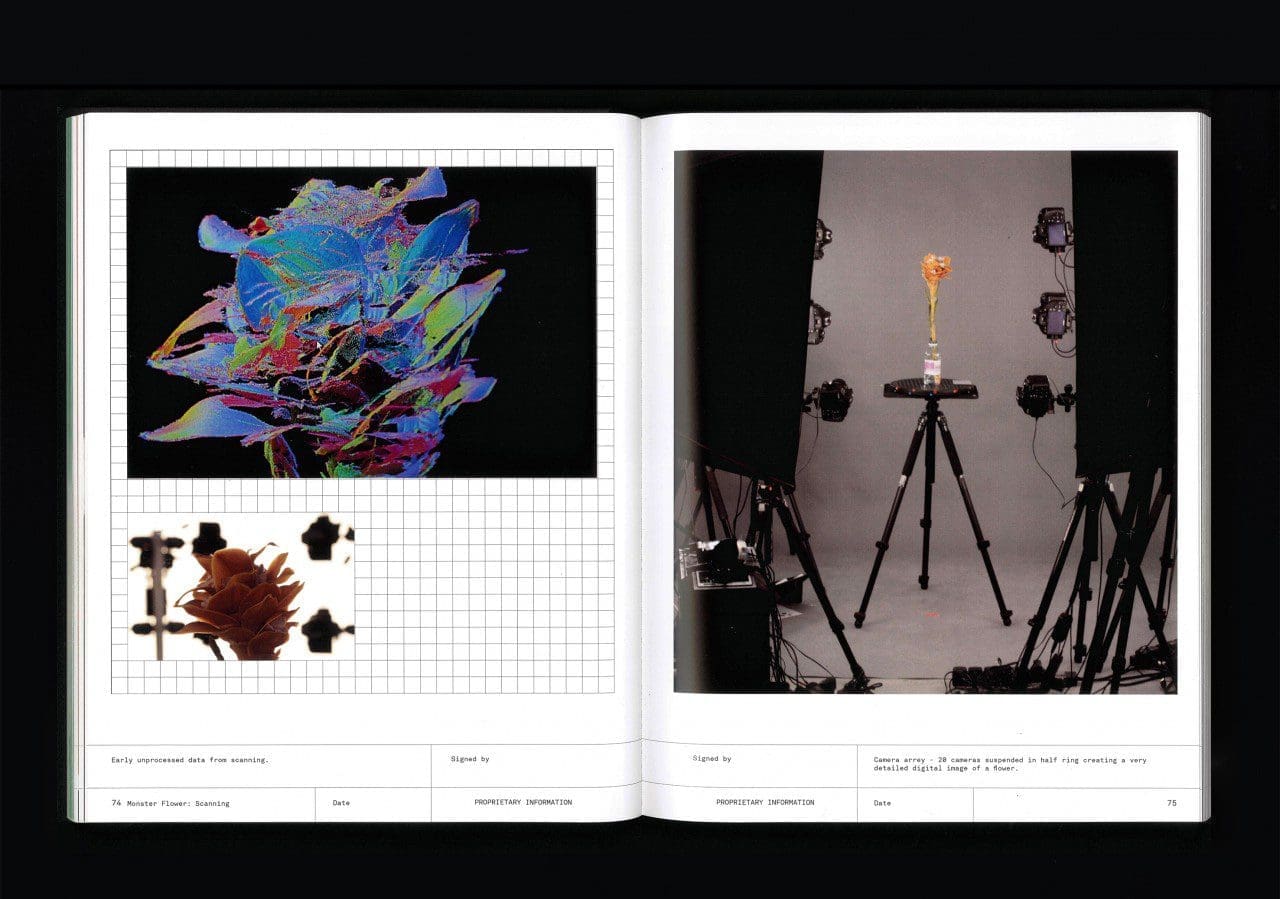

We created a number of hybrids. Each one came from a purpose. The way that they look is accidental. We were never thinking about them aesthetically. So when I came to the UK I had about a day to scan the first one. We used a camera array – 20 cameras standing in a circle. They shoot constantly while the object is spinning and they build up a 3 dimensional digital image. However, this digital file has no functionality. It can’t be printed. So I hired a 3D sculptor, Ignazio Genco, who then spent two weeks re-sculpting the digital files on a computer, so that they could be printed. The original one was made out of 22 separate 3D printed pieces, with a steel structure inside. It took 72 hours of straight printing.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

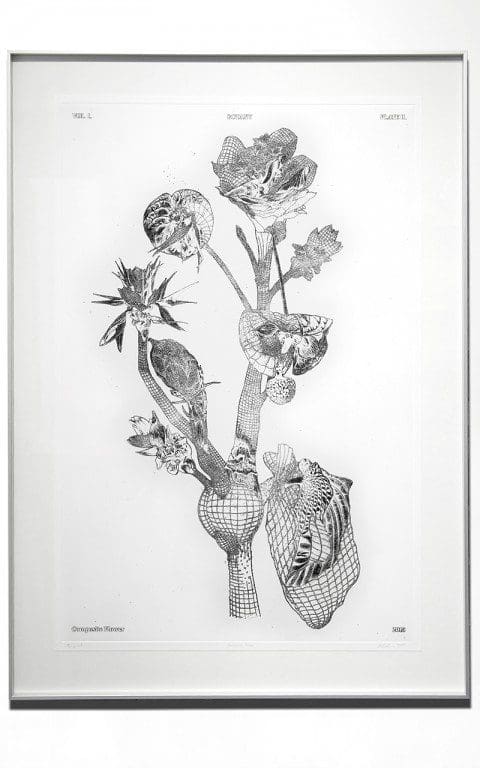

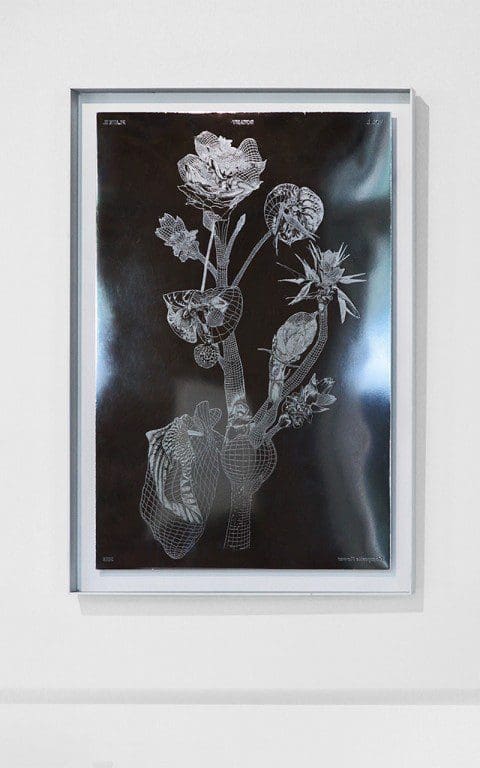

So that was the research, but I wanted to go further in telling the story. So I made these printing plates, like in the 16th century, when they discovered a new species of plant they would create a drawing of it and make multiple prints of it. So I started working with an illustrator, Clara Lacy, and we did it exactly as they would have done it, so we had the blow up details with information, we acid-etched it on copper, then we made the prints – monoprints in a run of about 15 – and then we chromed the plates to make them into permanent artefacts. I also produced a book of the whole process, as I wanted to extend the story as much as possible.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So that is how my practice works. Half of it is research, where I spend my time and money investigating what I’m really interested in, and then the other half is taking bits of it and translating it into ‘object’ work, which is where the recent resin work comes from. That all started with the research I was doing into aging materials. I was really interested in the ephemeral, the idea of value, the idea of things not being permanent.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Tell me how this vase encapsulates those ideas and values.

We have so many things around us that we don’t really necessarily want to keep – we are stuck with their materiality – like a mobile phone case for example, which is useless after two years, but you are still stuck with the object. So I started thinking of how to make objects that aren’t permanent.

So you have a vase like this, which is made with organic binders, tree resins, shellac, beeswax, cooking flour, and dried flowers. This one (Perishable Vase III) is made with shellac, which is a natural resin excreted by beetles. I mix it with flowers, which I collect and dry and process and organise in ‘libraries’. Then I make this material and then I form it in moulds to create the vases. Because it is made from organic and natural materials the idea is that, if you don’t take care of it – for example if you put it outside – within a month it would just disappear. So there is this contrast where you create something which visually you might appreciate, but you have this back thought that it will disintegrate if you don’t take care of it. So I wanted to get people to think about objects by making something that is not permanent.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III (detail).

Perishable Vase III (detail).

There’s also the idea that it is something you don’t have to have forever.

Yes. I wanted to make an inkjet printer with this technique – looking at the idea of planned obsolescence, where a printer is designed to print 5000 pages and then it breaks down and you have to buy a new one. So if you could use this material to make a printer body you could just dump it in your garden when it is finished with and it would rot. But this material is so far away technically from what you need from the body of a printer that I decided to create a more symbolic piece, which is a vase.

And then the investigation into nature is an extension of that, thinking of the process of aging, not necessarily actually disintegrating, because of course I do actually need to sell things, but I was really interested in creating a material that evolved, so that you don’t replace it, but you want to experience the change. In the way that brass or leather age and we appreciate it for what it is.

So I started working with this PhD research graduate from Kew, and we started injecting bacteria into flowers and casting them in resin. When resin cures it reaches very high temperatures, so the bacteria needed to be able to live without oxygen and at really high temperatures. So over time the bacteria destroy the flowers within the resin, but leave the form of the flower trapped in the resin. The idea was to create a material in which light would eventually replace the flowers within, like ghosts. I had this vision of this strong black resin and then light comes in and you only see the voids after the flowers have disappeared.

Then, instead of bacteria, I started using air, because air does a very similar thing. If you allow air into the resin then the flowers shrivel and die and gradually you see this halo of light around the structures. In the Flora Table you get this silvery effect. So the flowers don’t rot and go brown, they don’t disappear, they just start becoming silvery, with these voids of light around them. So a bit like a Flemish painting, but with the aging factor.

I was also interested in going back to this idea of natural decoration, how often we are inspired by nature to create decoration, but how rarely we use nature itself to create decoration.

I started casting the flowers in big blocks of resin and slicing them up and opening them almost like a cheese, and then misplacing the slices. Each of the slices in this screen comes from four different resin blocks of flowers. Sometimes I keep track of how I cut them when I reassemble them, other times they are arranged completely randomly.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Do you fabricate all of these pieces yourself ?

I did! It was really hard work. I made these pieces for an exhibition last September, and I was late with everything. When you are coming up with a new material there is so much to learn through the process. You think you know and you keep learning. I am still learning so much from this material. I didn’t know so much about resin at the beginning, so I made these moulds and added too much catalyst, and the resin started bowing because it was shrinking too much, it was curing too quickly. So I had to do a good few runs of resin casting to get the result I wanted. Then there was so much work with cutting them and sanding and so on.

Now the process is much better. I have specialists that I go to with certain things, but I still do all the flower collection. Until recently I was also doing all the casts on my own, but because each object becomes bigger and bigger – right now I am working on a commission for a 2 metre long table – so the scale of the project requires other people, more pairs of hands. So I work with resin specialists, metal specialists. I am still very engaged with the work. With the resin casting I do all of the arrangement of the flowers. I do a few arrangements at the same time and then choose the one that I like the best. It’s a bit like painting. You choose them for their structure, but also for their colours, volumes, and then make these compositions. Once I am happy with a composition it goes in to be cast. Still during the casting there are so many things that can go differently.

I use a mix of both dried and fresh flowers. I have the size of the mould, so I know what my ‘canvas’ is, and I have all my plant libraries, which I take with me. I have times of the year when I collect a lot, and dry them and then have to keep them dry. When I need fresh flowers I get them when I need them. And then I arrange them and then there is the casting procedure.

It took me a year to get to the point where the flowers weren’t burnt or shrunk by the resin, nor for the flowers to affect the resin curing, because if you put moisture into the resin it prevents it from curing properly. It’s a very slow process and took a lot of development to get there, but I’m not going to give away my recipes!

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

What is intriguing about your work is that it is clearly very complicated to produce and yet the pieces are very simple.

There is so much technicality that goes into it, and it requires a lot of specialists. It has also been a problem with my work that producing it was really expensive at the beginning when I was producing in a self-initiated way, rather than with commission-based work. And when you are a recent graduate you find it really hard to do, which is one of the reasons, to start with, I did everything myself.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table (detail).

Flora Table (detail).

Are you primarily being commissioned to produce the furniture items at the moment ?

Yes. Actually creating the furniture work – the easiest to understand for people – has helped with the appreciation of my other work. People started getting the idea of the decaying vases much better and so I started getting commissions for these too, and now I am doing these resin pieces made in the same way as the screen, that are more like paintings. They will be framed and can also be used as wall panels. So half my work is commissioned work, and the other half is just me putting time and effort into investigating new things.

What are you working on right now ?

Right now I am working on a flower incubator. It comprises this desktop ‘machinery’ – all of the parts form a complicated system of water exchange, temperature control, hydroponic nutrition – designed to prolong the life of a cut flower to see how much longer we can possibly extend its life. So this is the opposite of the idea of constant disposable consumption. It is taking something that is already starting to decay and attempting to give it longevity.

The incubator is technically a very challenging project, and so I am having a lot of help with different specialists, so it is taking much longer than previous projects. Generally I have realised that I must take as much time as I need to develop what I want to do, rather than pushing things too quickly. It’s quite easy in this world to get trapped into working with other people’s deadlines, especially interior designers, as aesthetically the resin pieces are being seen as statement pieces for interiors. So currently I have quite a lot of enquiries from interior designers wanting to use these furniture pieces in their work.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

How do you manage that in terms of how people perceive your work ?

I am only just starting to realise that there are these differences between, say, the interiors world and the art world. When I started, for me it was all the same, I didn’t really know. Because I’m so interested in the idea and what these pieces are conceptually the selling outcome was something far from my mind. Now I am starting to distinguish how much work and commitment actually goes into creating a working piece of furniture. The resin material gives them an added value, but what I am most interested in is creating the value in the material itself – by the fact that it ages, or is not permanent.

So I am trying to shift my practice right now into this world where the pieces are appreciated for the conceptual idea. I spend quite a lot of time going out and talking to people, giving talks, to explain the work, because if you put a vase like this on a plinth and you just leave it as it is without a label people just say, ‘Yeah, it’s a vase.’, but if you give the story of why it was made and what it’s going to do in a couple of years they really perceive it differently. So the longer I am working the easier it is to make the work because people already understand it. At the beginning it was really hard to come up with the idea and have people understand it. The furniture pieces give people an easier point of entry, as people like them first for their visual aesthetics, and then when they get deeper they realise that there is this whole body of work. Of course, aesthetics are a very important part of my work. Not as the ultimate outcome, but more as the result of an investigation into aesthetics, either through making natural decoration or the aesthetics of things that decay and don’t last. I think aesthetics are incredibly important and we should never forget about them, but they are never the primary goal in my work.

So where do you see your work going ?

There are still two paths currently. One where it is more applied fine arts, and the other is me investigating this idea of impermanent things. I’m in a group show in September. I’m doing more of the vases for the show. And I’m thinking of making a decaying glasshouse where the front of it is so fine that it just disappears. That’s something that really stimulates me and gives me energy to work.

It’s also a lot about grabbing from the pool of inspiration from the past and mixing it with everything I am doing right now, like the story of flowers and the consumption aspect. One feeds the other, and then they start to feed themselves. So I guess I’ll see where that goes, but I’m really about thinking through making, so I have to be making to come up with things. It’s never just me thinking about making something and then doing it, they are all an outcome out of the past research, my palette of tools and materials, and you go with all of them until something starts getting somewhere and then you pick the ones that go somewhere and start working on developing them further. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go. I’m working on having a different creative head space where it’s all about making, so just letting myself make mistakes and experimenting.

Nowadays we are so keen to have ‘new, new, more, more’ all the time, I am trying not to get trapped in this way of thinking and take time to actually develop these approaches I have started as far as possible. My practice is also a lot about people being able to come and see the pieces, so I am really happy to now have a space where I can meet people and show them the work and explain the ideas. For it is one thing to see an image on the internet, but quite another to come and talk to me about where it’s coming from, and also the possibilities of what I can make for them.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology (detail).

Flower Entomology (detail).

Can you tell me about your relationship to nature, gardens and flowers ?

I would say that it keeps coming more and more. I started off as a blank page where I was interested in other things, but the more I work with these objects the more I appreciate nature. I have started thinking about flowers very differently. I don’t have this need to have them around me so much, as I look at them as a kind of material, and I see so much waste that it terrifies me to even think about going to buy more of them, and I don’t have a place where I can grow them as I live in central London.

Strangely plants have become a lot more intriguing to me, also because of my investigations and my talks with plant geneticists, but on just a very personal basis they have become much more, I would say, friends, where they are just this amazing source of nature you can hold in your hand. My room-mate shares the same idea and we now have more plants in our flat than I think we do cups ! It makes home so much more relaxing, especially in London.

And if you think that my past was in this 2 acre central Warsaw garden – because not only did we have the glasshouses, we also had a very particular garden, because my grandfather grew not only flowers, but all the garden plants as well. Then I lived first in the Netherlands, a small city with not all that much nature around, and now I am in London, and I am missing it a lot, which is why I have this desire to go and be in nature every now and then.

My sister and I have also just started a business together around flowers, doing artistic flower installations in Warsaw, because first of all it’s something that she is really into – it is in her DNA, she was never trained – but she just makes these amazing compositions and arrangements, and there is a big niche there for that there, as all the florists are doing the same kind of thing. No one is really thinking of flowers in terms of them being local or seasonal, or in working on the composition almost as a sculpture or painting. We’re using the same name as my grandma used to call her flower shops, which is MÁK, which means poppy seed in Polish. We only started about 4 months ago and so I am travelling to Warsaw a lot more at the moment, because we are doing this together, as she’s very young, she’s 25, so I am trying to support her, but she is the main engine and inspiration, she does all of the compositions herself. And she dries flowers for me too. She uses lots of flowers in her installations and everything that comes back to her is being dried and re-used in my work.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

What would your grandfather think ?

I’m really curious. He was a very complicated man with a very complicated way of connecting with his family so I didn’t really know him that well, but I think he would be secretly really intrigued and interested. I sometimes wonder what it would be like if I could go home and talk to him about these things and get his knowledge. My sister is always seeking knowledge about plants and my mum tries to give us as much of her knowledge as she can, but I think my grandfather would be an amazing source. Lately I have been digging through all the family archives and going through everything, because I have been trying to find a book of his – you know when you are a grower and you discover and record things for yourself ? – so I’m trying to find these transcriptions of what he was doing.

We had four or five really big glasshouses, and it was funny as it was in central Warsaw and he sold it to a development company, who took down the glasshouses, but they promised to keep the garden, because that was his condition. But they tricked him and they took it all down and built these big buildings and only kept a tiny bit of the garden. It was really sad, but we managed to rescue all these massive trees, and they were transported to my parents house on these huge trucks. They had to wait to build the house until the trees had been planted first.

Your work straddles worlds of art, craft and design. How do you classify it ?

With the craft, I think I was kind of put there more than it was a conscious decision on my part. But it’s so close to everything. It’s hard to even name it for myself. Like, when people ask me, “So, what do you do?” I seriously have problems answering this question. And it’s not because I’m trying to be so ‘artist’ about it. It’s just, how do you explain that it could be objects that don’t last, or it could be research in the Netherlands, or it could be investigating an actual decoration and making these resin pieces, or it could be ephemeral textiles ?

It is hard these days to say what it is. I don’t feel the need, or able, to classify it. It is what it is. It is other people who need it to be classified. That is fine with people who are open, and who are prepared to listen to me explain the ideas behind it, but closed people find it harder to grasp the idea of buying something that is ephemeral. It’s hard for some people to see value in something unless everyone else does. Some people at the design fairs have said that my work shouldn’t be categorised as design, but really that is just a tag for it. How people see it is how they see it.

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage