ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

The spring this year has been slow. A wet winter finally giving way at the end of February to a long and testing period without rain. This came with a relenting fortnight of frosts that saw us fleecing the wall-trained fruit nightly and praying for the plum orchard, which at the time was in full and vulnerable flower. It has been too cold to direct sow in the kitchen garden and the self-sowers, which I like here to make the garden feel lived-in, are looking sparse, the seedlings dwindling without the water in the top layer of soil in this critical period.

We knew the garden would find the water with well-established roots searching it out, but new growth needs rain and it began to show it in tardiness and a reluctance to get out of the blocks. This spring we have pined for the burgeoning that is so much part of an April landscape.

Cue the tulips which, although slower to appear than usual, have sailed through unscathed and oblivious. Miraculous for their ability to cover for the pause between the narcissus waning and the cow parsley filling the hedgerows, we would not be without their impeccable timing.

Despite the hiatus in the garden and their ability to plug the gap, I have deferred from including tulips there due to their immediately ornamental nature. Preferring the slow unravelling of greens against our rural backdrop, we have, instead, grown the tulips in the kitchen garden for picking where, in this productive setting, their flamboyance can sing and not shout.

It was on a trip to see the Dutch bulb fields while a student at Kew that I first saw tulips jumbled together en masse. They were in an old orchard at the back of a bulb farm where the spares had been thrown and provided (for me at least, desperate for naturalism) a relief from the rigour of the regimented rows in the fields. It was an unforgettable sight. Free and liberated and multi-layered with colour and juxtaposition of forms. We grow them together here in homage to that memory and to ease the tulips’ innate formality.

Each year we put together a collection that explores a particular colourway using early, mid-season and late varieties so that we have a month to six weeks of flower. Thirty of each and usually ten varieties planted randomly about 6” apart in November. We move the tulips from bed to bed so that they appear in a different place in the kitchen garden to avoid Tulip Fire, which builds up if you replant the tulips in the same ground repeatedly. A five to seven-year cycle means that the fungal disease goes without its host and, by the time they return to their original position, the ground should be ‘clean’ and ready to receive them again.

The annual selection sees us experimenting with new varieties, and returning to old ones that we favour. Inevitably, because one tulip bulb looks roughly like another, we curse the bulb suppliers who substitute one or two without letting us know so that there are some wild surprises. This would matter if you were planting them into a scheme, but it rarely matters in the mix and sometimes throws up an oddly welcome guest.

After ten years of enjoying growing the tulips in the knowledge that they provide us with a guaranteed respite after winter and a kickstart in spring, we are beginning to feel less easy about their disposability. We are particular here about reusing what we can and not more than we need and it goes against the grain to discard the bulbs, because we don’t have the room to keep them. So, a new place, which will be our equivalent of the Dutch orchard, will be found by the polytunnel for the bulbs to have another life and show us which ones have the potential to be recurring in our heavy, winter-wet ground. This may take some time, but it feels the right time to apply this rigour.

In the search for varieties that do well year after year, we are going to try a few in the garden, but only close to the buildings and used very sparingly so that they do not compete for attention. They will be worked in amongst the volume of the Paeonia delavayi at the garden’s entrance, so that the early flower coincides with the unfurling plum foliage of the tree peonies. We are referring back to our 2019 selection that focused on dark reds and plums. The moodiness of the almost brown ‘Continental’ and the glowing cardinal red of ‘National Velvet’ will sit well here. We will let you know next year how the association fairs amongst the peonies.

In order of flowering our selection was as follows:

First to flower in early April and with a long season of over a month. Tall, straight stems. Uncommon shade of lemon sorbet yellow. Widely listed as growing to 40cm, we found it to be one of the tallest at 55-60cm.

Difficult in a garden setting as the flower is so out of scale with the stem length, for cutting this wine-dark tulip is rich and lustrous. Almost as good as the peonies it precedes. Long flowering season. The shortest for us at 30cm, although listed at 45cm.

Opening primrose yellow with dramatic green flaming this lily-flowered tulip fades to cream and twists extravagantly as it ages. 40cm.

Another diminutive tulip better suited to a pot. A boxy shape we were not so keen on and a rather violent shade of scarlet in the garden. This mellows when cut and brought indoors though, where the exaggerated fringing and black eye can also be seen to best advantage. 30cm.

Delightfully elegant Viridiflora tulip with green flaming on gently waved petals of off-white, broadly streaked with raspberry red. 45cm.

Similar in colour to ‘Orange Sun’ which we have grown before, this Darwin tulip is taller and more elegant. The pure, citrus orange flowers have a satin sheen and a clear yellow centre, which is shown when the flower opens in sunshine. 50cm.

A more sombre shade of burnt orange which is accentuated by the matt petals, which age to faded apricot-gold at the margins. Deliciously sherbet-scented. For us this was the shortest lived at just two weeks. 45cm.

The court jester of parrot tulips. The flaming of primary red and yellow is utterly joyful. The yellow fades to a more subdued clotted cream as they age. 50cm.

Late and tall this tulip has huge flowers the size of a goose egg in a rich shade of deep crimson. With sturdy, ramrod straight stems it is ideal for a windy site such as ours or for picking. 55-60cm

The scarlet lily-flowered tulip in the main image is ‘Red Shine’, which we grew last year and would seem to be a good contender for perennial flowering.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs & captions: Huw Morgan

Published 8 May 2021

The gales have torn at the last of the autumn colour, the rain is with us again with apparently no let-up, but open the door to the polytunnel and you enter a world that is stilled. Immediately calmed and weather-protected. The drum of the storm amplified yet distanced.

This is a place we are getting to know and learning about through growing. Ordered in the first lockdown and erected just before we came out of it at the end of May, the summer’s crop of tomatoes, cucumbers, basil and chillis is now replaced by winter salad. Hunkering down in an environment that takes more than the edge off the winter, we can already see the benefits in the enabled growth. The complement to the hardy winter vegetables in the kitchen garden.

The polytunnel is also providing sanctuary for another crop we are growing to keep us buoyant as the evenings lengthen and the growing season retreats for good. Brought inside at the beginning of October to escape the elements, the spider chrysanthemums are at their very best and, indeed, most vulnerable as the weather turns. Though I grew them successfully for a couple of years in the microclimate of our London garden, last year’s attempt at growing them outside here ended in tears. Months of care and promise were destroyed by November frosts, the very first flowers left in ruins and buds blackened beyond hope.

Not to be daunted, an order was placed with Halls of Heddon last year without a specific plan for their autumn protection. Such is the way with failure in a garden, it often spurs you on to succeed. The rooted cuttings arrived in the spring, this year with the promise of the polytunnel as an autumn retreat, so they were potted on and placed in the lea of the barns up in my growing area. Here, they received morning light – the four to six hours they need to set flower – and then afternoon shade. They were carefully staked and given not much more attention than a regular liquid feed to help flower production.

I confess to preferring plants that one can nurture towards independence to those that are reliant on human intervention, but the chrysanthemum festivals in Japan are enough to subvert my self-imposed rules. Once the leaves are down on the fiercely coloured maples and twiggery presents itself again to grey skies, they take a special place in the descent into winter. Grown often just one flower to a stem, displayed on a plinth and often against a dark backdrop, the blooms are naturally likened to fireworks.

My plants this year have, by contrast, been neglected. They were not pinched out to promote appropriately spaced branching, nor dis-budded to select a number that can put all their energy into flower. They have had the minimum of care. A chrysanthemum grower would say mistreatment. But here they are, in the shelter of the polytunnel, coming into their ethereal own as the rest of the world outside begins its slumber.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 November 2020

The sweet peas are an investment. A good one with the promise of marking summertime, but one that is not without a requirement for continuity and a little-and-often attention. The rounded, manageable seed is easy. A finger pushed into compost and three seeds per pot for good measure. Sown either in the autumn and overwintered in the frame for a little protection for the strongest plants and earliest flower or, alternatively, at the first glimmer of spring in February. You have to watch if the mice are not to eat the freshly sown seed before it has even germinated and, although perfectly hardy, they like good living once ready to go out in April. They require good ground, with manure or compost and plenty of moisture to send their searching growth up into a carefully managed cage of supports. We use hazel twiggery from the coppice here. Helping their ascent, so that their soft tendrils are trained within easy reach for picking, another part of the daily vigil. And finally, once they start to bloom, you need to keep on picking to keep the flowers coming if they are not to go to seed.

All in all the rewards are forever worth it and the jug sitting beside me, with the whole room perfumed of summertime is testament. Their vibrancy is the personification of long days spent outside doing and the elongated evenings that stretch ahead until bedtime. We spend this valuable time looking and find the evenings and early morning the best time to pick them, for the cool flushes their flower and helps in keeping for longer. The evening bunch for the bedside and the morning bunch for the kitchen table. Pick and you can keep on picking every other day and, when the plants finally begin to run out of energy in August, you will be sure to feel the next season coming. The weight of harvest and in the case of the Lathyrus, the desire to go to seed, which we make allowance for when the stems get too short to pick so that we can save some.

We grow two batches of sweet peas now. Named varieties of the Old Fashioned sweet peas, which we buy new every year from Roger Parsons and Johnson’s. Selected for their perfume and not length of stem we grow them up informal hazel wigwams in a strip of land we call the cutting garden. These are an ever-changing selection as we add to and subtract from a variable list as we move through new varieties and revisit ones we’ve grown to love. These selections have plenty of Lathyrus odoratus blood coursing through their veins and we like the fact that you can feel the parent and that they have not been overbred at the expense of their stem length, flower size or perfume.

Set to one side and grown amongst the perennials in the main garden are the pure Lathyrus odoratus. We keep them apart because the seed was collected by the plantsman and painter Cedric Morris on one of his journeys to Sicily. The direct line has been carefully handed down to custodians who knew the importance of continuity. First, directly from Cedric to his friend Tony Venison, former Gardens Editor of Country Life, and then from Tony to his friend Duncan Scott. Meeting Duncan was a chance happening, as he is the neighbour of a client who thought we should connect. Duncan knew of my friendship with Beth Chatto, who in turn had learned directly from Cedric and had many of his plants in her nursery.

Duncan’s seed was handed over in a brown paper bag with the inscription ‘Cedric’s Pea. Lathyrus odoratus, collected in Sicily’. In turn I have recently had the pleasure of sending seed on to Bridget Pinchbeck who has taken on the responsibility of restoring Benton End, Cedric’s house and garden in Suffolk, to become a creative outpost of The Garden Museum. A full circle made in not too many leaps of the gardeners’ weave and easy generosity.

I am very happy to help keep the line alive and to pass it on, as we have spent much time looking through Cedric’s eyes over the years. First with plants that Morris gave with stories of their provenance to Beth Chatto and her in turn to me. And then through his dusky almost-grey and pink selections of Papaver rhoeas and latterly his Benton Iris which we grow here and treasure. Lathyrus odoratus was first introduced in 1699 by the monk Francis Cupani, the name which you will often find the pea listed under. I wonder whether Morris made his trip to Sicily in Cupani’s footsteps to find the pea for himself ? Regardless, it is good to imagine the find and relive his undoubted excitement at it. The vibrancy of the flower, with its vivid coupling of purple falls, wine red standards and the halo of unmistakable perfume.

It is Cedric’s lathyrus which is the first of our sweet peas to flower. A whole two weeks earlier than the named varieties and still the most perfumed of all. When we walk the garden in the late half-light of June, it is with an invisible orbit of scent that stops you on the path. The late light or early morning are the best times to see their colour. Clear and sumptuous and well worth the effort of continuity.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 June 2020

There was a heavy frost this morning and we were suspended for a while in a luminous mist. The wintry sun pushed through by lunchtime, the melt drip-dripping and the colour of thaw returning as the unification of freeze receded. Undeterred the Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ emerged unscathed, liberating their sweet honey perfume in the sun.

We went on a hunt for flower to see what there might be left for the first winter mantlepiece. The pickings, now rarefied, feel held in a season beyond their natural life. A rogue Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ misfiring, but welcome for the reminder of the hot violet which you have to imagine as you move the seedlings around to where you want them to be in the autumn. My original plants, a dozen grown from seed two years ago, are now gone. Last year’s pennies threw down enough seed immediately beneath to need thinning and the transplants allowed me to spread a new colony along the lower slopes of the garden. Being biennial, it is good to have two generations on the go so that there will always be a few that come to flowe,r but enough to run an undercurrent of lustrously dark foliage in winter. It is never better than now, revealed again when most of its companions have retreated below ground.

The reach of the Geranium sanguineum ‘Tiny Monster’ is now pulling back to leave a shadow where it took the ground in the summer. It has been flowering since April, brightly and undeterred by all weathers. This larger than life selection of our native Bloody Cranesbill shows no signs of stopping as the clumps steadily expand. It is a slow creep, but a sure one. Short in stature at no more than a foot, you have to team it carefully if it is not to overwhelm its neighbours. We also have the true native G. sanguineum, grown from seed collected from the sand dunes on the Gower peninsula in Wales, and teamed with Rosa spinosissima from the same seed gathering. The two make a fine match, the geranium scrambling through the thorns of the thicket rose.

The pink Hesperantha was a gift from neighbours who gave us a mixed bag of corms including the earlier flowering H. coccinea ‘Major’. This hot red cousin flowers when there is heat in the sun, but gives way to this delicate shell-pink form (which we think is most likely to be ‘Mrs Hegarty’) as the days cool in October. I am not a fan of delicate pinks, preferring a pink with a punch, but it is hard not to love this one when it appears. I like it for standing alone at this time of year and for not having to compete for being so very late in the season. In terms of where they like to grow though, Hesperantha hail from open marshy ground in South Africa so you have to find them a retentive position with plenty of light to reach their basal foliage. I have them on the sunny side of Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ which they come with and then go beyond.

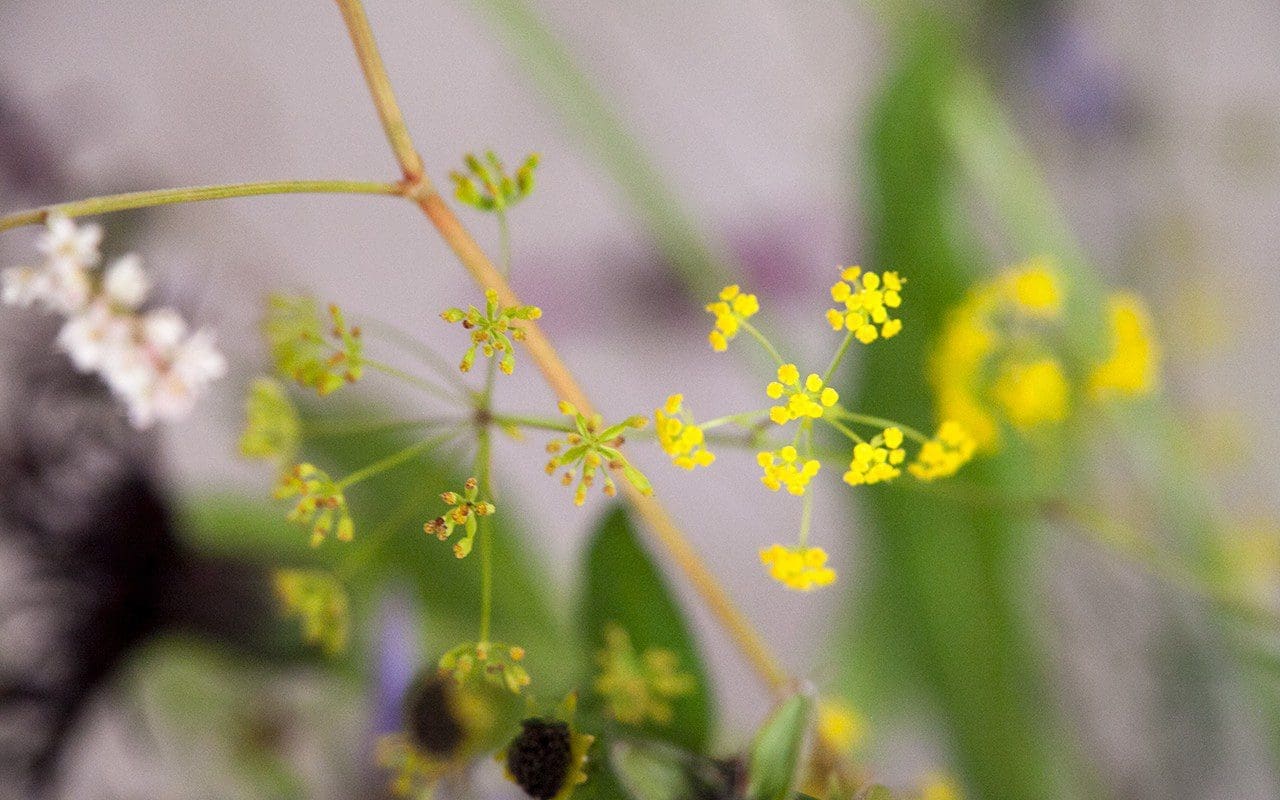

Equally hardy, and one of the longest-flowering plants in the garden, is the Scabiosa columbaria subsp. ochroleuca whose delicate pinpricks of lemon yellow are held high on wiry stems and are still enlivening the skeletons of Panicum and Deschampsia that are now collapsing around them. Even now they are a magnet for the hardiest bees and the odd peacock butterfly that ventures out in the weakening winter sun before hibernating.

Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ is our very last aster to flower, but its season is still longer than most. I love its simplicity and soft, moody colour, but it has been out for so long now that sometimes I forget to look. This is one of the joys of the mantlepiece and of hanging on so late to make you refocus. Not so Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’, for it is hard to pass by this strength of colour in the gathering monochrome of winter. I have given our plant the most sheltered corner I have, because it is always trying to push growth which gets savaged by cold winds. Here, in the lee of the wall at the end of the house, it flowers intermittently, often through January, paled then by the cold, but always welcome. Close by and also basking in the shelter of the warm wall is Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’, another plant that would continue to flower uninterrupted if we did not have the freeze.

Next year I will protect the spider chrysanthemums, which come so late and need it to survive the frosts. This is one of the few that have survived the recent cold spell. I have not grown ‘Saratov Lilac’ before, but have taken cuttings which are in the frame to try again next year. I have also ordered several more to test my end of season resolve and hope a make-shift shelter of canes and sacking will suffice when the weather cools in October. We got away with it when I grew them in London, but not here where the frost is reliable and helps us to respect the season.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 December 2019

We have just returned from Greece and a browned and dusty landscape that had not seen water since April. We arrived back to a season changed. Fields deep and lush with grass, hedges flashing autumn colour, dimmed as they reached into a shroud of drizzle. Our distinctive line of beech at the end of the valley all but hidden by cloud and windfalls shadowing the slopes beneath the apple trees in the orchard where, just a fortnight before, the branches had been weighted. It took a day to retune the eye, but here I sit not a week later with the sun streaming in over my desk and the studio doors wide open to the garden. It is the stillest, most perfect day of autumn and the garden has weathered well. Aged too by the window of time we have been away, but certainly not lesser now that we are in step again with the season. Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018 Today’s posy draws upon some of the fine detail in our fully blown August garden. A garden arguably never more voluminous and drawn together now with a growing season behind it. Look up and out and your eye can travel, for the grasses and the sanguisorba are asserting their gauziness. The first of the asters are beginning to colour, in wide-reaching washes that I’ve made deliberately generous. At this time of bulk and volume, however, it is also important to be able to look in and find the detail in something intense, finely drawn and requiring close examination.

Most of the flowers in the garden here are deliberately small, so that they feel part of the place and cohesive with the scale of the surrounding meadows. Some, like the sanguisorba, appear en masse and register together to create a wash or a veil through which you can suspend an intensity of contrasting colour or screen another mood that appears beyond it. The Bupleurum falcatum, which has now seeded freely in the gravel garden, does just this in the posy to enliven the mood with it’s fine, acidic umbels. At another scale, the Fagopyrum dibotrys does the same in the borders, towering tall and creamy. This perennial buckwheat is prone to wind damage, snapping rather than flexing, but I have found it a sought-after niche close to the buildings to help to narrow the feeling alongside the steps. The scale of its flowers, and their airy distribution, is why it retains a feeling of lightness.

Bupleurum falcatum

Bupleurum falcatum

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Althaea cannabina

Althaea cannabina

Some plants are more interesting for having to find, but their subtlety requires careful placement. The Clematis stans was initially planted down by the barns whilst I was seeing what it was going to do here, but it has been good to have it closer for the detail in the flower is up to regular inspection. This herbaceous clematis is rangy when growing in a little shade but here, out on the blustery slopes, it makes a compact mound of a metre or so across. Prune it hard to a tight framework in February and it rewards you quickly with bright, expectant leaf buds and then foliage that is elegantly cut and not dissimilar to Clematis heracleifolia. In high summer, when the light levels change, it begins to produce clusters of powder-blue flower buds which taper and colour as they move toward flower. Reflexing just the tiniest amount to form a bell like a hyacinth, they have a delicate perfume, which is lost if you bury the plant too deeply in a bed.

Clematis stans

Clematis stans

![]() Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Earlier, in the heat, I was beginning to debate whether I’d take out the Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’, for it appeared to hate the brilliance of this summer and the exposure. Already a plant of some modesty, the relief of rain has them with flushed new growth to prove me wrong and it is a delight to come upon it, for it has to be found. The dark, filamentous flowers are as dark as blackcurrants, but combined with silvery Lambs Ears (Stachys byzantina), they are thrown into relief. The hunt is furthered by merging the groups with four-leaved black clover (Trifolium repens ‘Purpurascens Quadrifolium’) and Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. The clover is actually brown, and the potentilla punches colour strongly, but in tiny pinpricks that flash and then disappear as they open and close during the day. Walk the path in the morning and they will be blinking bright, but walk it again in the evening and they are closed, clocked-out for the day.

Pelargonium sidoides

Pelargonium sidoides

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

Over time, and now that the garden has grown and is demanding my attention, I’ve limited the number of pots up around the house. The Pelargonium sidoides are an exception and these are my original plants from what must now be twenty years ago. They have proved their worth despite their subtlety, but I help in having them close by the front door. They are grouped with pots of Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’. Early in the season and before they start their relay of flower, you might at first think that a potful of tulbaghia were chives, for the majority have a lingering garlicky perfume. The confusion of flower and savoury association is not always digestible, but this selection from Paul Barney at Edulis is an exception. The leaves do not smell and the perfume of the flower is delicate and sweet, particularly at night. They continue to push out flower from June until the frost, when I move the pot to the frame and deny it water for the winter and they survived last winter to prove their resistance when kept on the dry side.

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Succisella inflexa

Succisella inflexa

There are several new additions to the garden this year on which I am keeping a close watch and reserving my judgement, but Geranium ‘Sandrine’ looks promising. It is a little larger flowered than G. ‘Anne Folkard’, but it has a similar rangy habit and bright green foliage and will find its way amongst other plants, so far without dominating. The flowers, which with many perennial geraniums are bang and bust, do not come all at once, but stagger themselves throughout the summer. This makes them more precious and they pulse with their darkly-veined centres. Succisella inflexa, a Balkan perennial, is entirely new to me, but this looks good for being so late in the season. Finely elongated foliage scales the stems, but stops to leave the thimbles of pale lilac flower hovering at knee height. It has a similar presence to Devil’s-bit Scabious, which is flowering now too in this window between summer and autumn. We will see if it comes back with good behaviour next year, but for now I am watching closely.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 18 August 2018

The last few weeks of growth have been remarkable, the volume and intensity lusher for the wet start and the thunderous, still growing weather. In this lead up to summer the garden was texturally wonderful, the layering of foliage acute for the absence or scarcity of flower. Finely divided mounds of sanguisorba, spearing iris and mounding deschampsia all readying themselves, but yet to show colour. A sense of expectation and the build up to the first round of early summer perennials we have today in this posy.

The colour in the garden is designed to come in waves, like a swathe of buttercups in a meadow, that leads your eye from one place to the next and builds in intensity and then dims as the next thing takes over. After an awakening of single peonies, the salvias are the next contrast to the foundation of greens, which I like here for their ease in the landscape. Though I have never found our native Meadow Clary (Salvia pratensis) on the land, it felt right to bring it into the garden in its cultivated form. We have two named varieties which are early to show and good for their verticality. Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, a rich, well-named blue and Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’, which was planted last autumn and is flowering here for the first time this year.

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Where ‘Indigo’ is perfectly named, ‘Lapis Lazuli’ has nothing of the intensity of the stone it is named after, nor of the ultramarine pigment derived from it. I have a nugget on my windowsill which I found once in Greece, sparkling in crystal clear shallows and catching my eye like a magpie’s. Although I was expecting something brighter and cleaner in colour like my find, the clear, soft pink of ‘Lapis Lazuli’ is anything but disappointing. It has been in flower now since early May for a whole three weeks longer than it’s cousin ‘Indigo’, rising up to two feet in widely spaced spires from a rosette of puckered, matt foliage. I expect it to still be looking good at the end of the month, but shortly before it starts to run out of steam, it will be cut to the base to encourage a second flush.

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

The first cut back is always hard, because the salvias are a magnet to moths and bees, but we performed the same severity of cut on ‘Indigo’ last year and it rewarded us with a new foliage and then flower in August. Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, the second of the salvias in this posy and far better named for it’s jewel-like colouring, will also respond to the same treatment, but it is important to act before the energy has gone out of the plant by curtailing its show before it finishes flowering naturally. Energy put into seed will thus be saved and replaced with more flower and the reward of fresh new growth.

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

The cirsium and the cephalaria are also encouraged to produce a second round of foliage by cutting them to the base immediately after they flower. Though they are less inclined to throw out more flower, refreshed foliage is just as useful in an August garden, which needs the greens from this early part of the summer to keep the garden looking lively. The Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ in this bunch grows down by the barns, where its early show coincides with baptisia. Though not remotely blue – a theme that is coming through in this posy, it seems – I love the bluer purple of this form just as much as the garnet red of the Cirsium rivulare ‘Atropurpureum’. These early thistles like plenty of light around their basal clump of foliage and look best for having the air you need to appreciate the way their flowers are held high and free of foliage.

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea is similar in its requirements and looks best when it can punch into air without competition. I grow it as an emergent amongst low Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ at the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido, where they grow ten feet tall on either side of a winding path. The creamy yellow flowers are delightfully sparse and the terminus of a rangy cage of airy growth. Here on our hillside they grow six or seven feet at most and right now appear head and shoulders above their partners. A single plant will leave a sizable hole in a planting if you choose to fell it after flowering, as I do for fresh growth, so it is wise to combine it with later performing partners that ease its temporary absence. Asters, grasses and sanguisorba cover for me here.

I have two more species that are part of the new planting and will flower for me for the first time here this year. Cephalaria alpina is a smaller cousin which is more delicate in all its parts, terminating at about four feet and forming a low mound of divided foliage. Cephalaria dipsacoides, teasle-like in its naming and also in its vertical nature, is up to six feet tall, but grows upright from the base. Creamy in colour like its cousins, but differing from all the plants in this posy in being later to flower and prolifically seeding if it likes you. Although I love its seed heads and the structure they offer the autumn garden, I will be cutting the plants down prematurely before they seed. A practice I am having to employ here with several of the self-seeders, as I do not have the manpower to manage the progeny.

Knautia macedonica

Knautia macedonica

A case in point being Knautia macedonica, that I will now treat as a useful filler where I need something fast and reliable. Our ground is almost too rich for this pioneer and in year two the plants splay fatly where they have been living too well. It too seeds prolifically, and my failure to deadhead them last summer resulted in a rash of seedlings this spring, which showed that it could be a problem if left to go native. A few seedlings on standby, however, will provide me with gap fillers where I need them and a succession of this ruby-red scabious that hovers amongst its neighbours. We pull any pink seedlings, favouring the bloodline of those with darker genes.

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea, the Giant Oat Grass is a plant that I have not grown since Home Farm, where it was a mainstay of the Barn Garden. For a while this grass became so fashionable that I avoided using it, despite its obvious beauty and, without enough room to grow it in the Peckham garden, I gave myself a breather. However, I am very happy to have it back and have given it the room it needs to look its best and for its low mound of evergreen foliage to get the light it needs. Right now it is at its most captivating, the lofty panicles, pale copper before turning gold and heavy with yellow pollen, dancing lightly to catch the long evening light. It is an early grass, bolting sky-bound plumes in May and taking June in a shower of luminosity and light.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 June 2018

A year ago now, and with the prospect of planting up the final part of the garden in the autumn, I wanted to add some variety to the range of plants that was available from my favourite nurseries. So, I set about sowing some additions from seed, to feel that I’d grown them from the very beginning and to understand them fully. Bupleurum perfoliatum and Aquilegia longissima were needed in quantity to weave into the new planting and to jump around, as if self-sown. It was also good to revisit plants that have become hard to obtain, such as Aconitum vulparia, a creamy wolfbane from Russia which I’d grown as a teenager and had a hankering for again.

The success stories of the plants I knew and understood were reassuring. Those that I didn’t, vexing but fascinating nevertheless. It is a mistake to throw out a pot of seed that hasn’t germinated within a year, because it may simply be waiting for its moment. The Viola odorata ‘Sulphurea’ needed the freeze of a winter to break dormancy and I learned by chance that Agastache nepetoides needs light to germinate, and so should be surface sown. My usual top dressing of horticultural grit, used to prevent moss and as a slug repellent, was washed from the sides of a pot by a leaky rose, opening up a window of opportunity, the seed germinating there and there only to burn this fact into my memory. Some seed may have been too old by the time it was sown, with very poor germination on the Anemone rivularis, but the small numbers mean that the plants that made it are that much more precious. Although the value of seed-raised plants increases when you have tended them from their vulnerable beginnings, it is also good to feel that you can be generous, because some plants are just so easy.

Having grown the biennial Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ the year before, the first plants had all flowered and seeded so an interim generation was needed to set up a continuity. The large, flat seed threw out fat cotyledons in a matter of days and the distinctive purple-tinged foliage was already there in the first true leaves. Where the perennial Anemone rivularis took their time to build up strength for the life ahead of them and had to be watched because they were so slow, the pioneering nature of the Lunaria means that you have to keep up to make the most of the growing season. The seedlings were potted on into 9cm pots as soon as the first true leaf was properly formed, handling the seedlings only by their cotyledons and never their vulnerable stems. With the new opportunity of their own space, they worked up a rosette last summer that was hearty enough to plant in the autumn and bolt the early spring of flower a year after sowing.

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Of the short-lived perennials I’ve used to provide for me early on in the life of the establishing garden, the Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora have been good to revisit. The white sweet rocket was a plant of my childhood garden, where it had sprung from the clearances of brambles like a phoenix from the ashes. Rising up fast with the cow parsley and easily as tall, its early flower bridges late spring and early summer. I have not had room to grow it for a while, because its ephemeral nature this early in the season can easily smother neighbours, to leave a summer gap when you cut it back to the rosette once it’s done. Let it seed and you will find a rash of youngsters, for it is also a pioneer that sees seedlings bulking up over summer in readiness to conquer new ground the following spring. This eagerness can easily be tapped, and it is good to leave a couple of limbs to go to seed as the plants are only good for two or three years before they exhaust themselves.

Sweet Rocket are adaptable to both an open position or to dappled shade, but the advantage of a cool position is that they grow less vigorously and take less ground. Mine were interspersed randomly in the planting to perfume the steps that descend to the studio and their distinctive, sweet scent is held in the stiller air caught behind the building. Bulking up fast once they were released from their pots, they have provided me with a rush of new life that has outstripped but complemented their slower growing neighbours. Seed-raised plants are more often variable and this is one of the joys of growing your own. Of the twenty or so plants, I must have almost as many different variants.

There is a blowsy head girl, brighter and showier than its neighbours and probably the one you would choose as a complement to a Chelsea rose garden, although she leans and topples under her own weight of flower. There is a perfectly behaved plant nearby. Just as white, but smaller and quieter and perfectly happy to stand upright without staking. This is probably the one that you would propagate from spring cuttings if you wanted something showy and reliable. My favourites have a wilder feel though; a grey-pink cast to some and more open flower panicles to others that provides the space I am so keen on and a lightness in the planting that feels less dominant. Head Girl has been used for cutting and will come out when I cut the plants down to prevent it from seeding and allow my slower-growing perennials around them the room they need to fill out later in the summer. Though the Actaea, the Zizia and the peonies are destined to provide a more certain future, the fast sweet rocket will always be just that.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan

Published 26 May 2018

It has been a long, slow start to spring, but at last we have movement. The snakeshead fritillaries are chequering the slopes behind the house and crossing over with early daffodils that this year were a whole two weeks late. The long wait will now see a rush as everything comes together, but reflecting the last few weeks of slim pickings we have kept things simple in this April gathering.

The wet weather has hit hard this year and Tulip Fire has run rampant through the tulip bed. We mass the tulips together in a random mix of six or seven varieties in the kitchen garden and experiment with a new colour palette and untried varieties every year. This year we planned for soft reds, pinks, oranges and apricots with an undercurrent of deep purples. However, we did not plan for the angst that has come with the mistake of replanting too soon in the same place. The Tulip Fire (Botrytis tulipae) probably came in with the bulbs that were grown in the same bed two years ago. A dry spring that year most likely limited its impact and it went unseen. This wouldn’t have been a problem if we’d not replanted in the same place for three to five years.

We will not be making the mistake again, for the majority of this year’s flowers are withered, pock-marked and streaked, the foliage melted on the worst affected. As soon as the flowers that are harvestable have been cut, we will dig up the bulbs and burn them on the bonfire. It has been a hard lesson after a long winter and one never to be forgotten, but we have managed to salvage enough to appreciate close up.

Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’

Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’

We will be trying Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’ again, for its faded pink exterior which conceals the surprise of a bright scarlet interior. The flowers enlarge and age gracefully, first to a strong lipstick pink before ending up a washed rose with the texture and shine of taffeta. It is said to be a variety that comes back for several years without the need for lifting, so next year I will try it by itself in some fresh ground. Planting in late November or early December when the weather is colder is said to diminish the impact of the botrytis should it already be in the ground. Grown on their own and not in the mass of different varieties, they may stand a better chance of staying clean. We have now kept a note to move our cutting tulips between beds on a five year rotation.

Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’

Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’

Tulips are remarkable for their ability to grow and adjust in a vase. The long-stemmed, large-flowered varieties exaggerate the quiet choreography that sees their initial placement becoming something entirely different as the flowers arc and sway. The complexity of colours in Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’ is promising. The raspberry pink blush in the centre of each petal is quite marked to start with, but suffuses them as the flowers age creating an overall impression of strong coral pink bleeding out to true apricot. The insides are an intense, lacquered orange with large black blotches at the base and provide voluptuous drama as they splay open with abandon. Though our choice of tulips has been somewhat pared back this year, it is good to have enough to get a taste of the selections we’d planned.

Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’

Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’

This is the first time I have grown the Crown Imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) here, and their story has been entirely different. Up early, the reptilian buds spearing the soil in March, and quickly rearing above the dormant world around them, their glossy presence has been so very welcome. I have drifted them in number on the steep slopes at the entrance of the new garden amongst the rangy Paeonia delavayi. Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’ has strong colouring with dark, bronze stems and rust orange flowers that work well with the emerging copper-flushed foliage of the peonies. Although there is an exotic air to the combination, it somehow works here up close to the buildings. It is a combination that you might imagine coming together through the Silk Route, China and the Middle East. However, plant hunters had already introduced the fritillaria from Persia in the mid 1500’s, and so it also has a presence that speaks of a particular kind of old English garden.

At the opening of the Cedric Morris exhibition at The Garden Museum this week Crown Imperials were a key component of Shane Connolly’s floral arrangements, scenting the nave with their appealingly foxy perfume. The smell is said to keep rodents and moles at bay and, though potent, is not unpleasant in my opinion. Morris’ painting Easter Bouquet (1934) captured them exuberantly in an arrangement from his garden at Benton End, which updates the still lives of the Dutch Masters with muscularity and vibrant colour. Rich, evocative and full of vigour, the paintings confirmed to me why we push against the odds to garden.

I planted half the bulbs on their side to see if it is true that they are less likely to rot, and the other half facing up. However, contrary to advice the two failures were bulbs planted on their sides. I also planted deep to encourage re-flowering in future years. The bulbs are as big as large onions, but it is worth planting them at three times their depth since they are prone to coming up blind when planted shallowly. In their homeland in the Middle East, they can be seen in the dry valleys in their thousands after the winter rains, so I am hoping that our hot, dry slopes here suit them. They are teamed with a late molinia and asters, to cover for the gap they will leave when they go into summer dormancy.

Bergenia emeiensis hybrid

Bergenia emeiensis hybrid

The third component in this collection is a pink hybrid form of Bergenia emeinsis. It was given to me by Fergus Garret, who tells me it was handed down by the great nursery woman Elizabeth Strangman with the words that it was a “good plant”. Sure enough, despite its reputation for not being reliably hardy, it has done well for me and flowered prolifically for the first time this year amongst dark leaved Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’. However, the combination was far from right, the sugary pink of the bergenia clashing unashamedly with the chrome yellow celandines. A combination Christopher Lloyd may well have admired, but not one that feels right here.

However, the elegant flowers are held on tall stems and the leaves are small and neat, so it has been found a new home in the shade at the studio garden in London, where it can be eye-catching when in season against a simple green backdrop. Though this recently introduced species from China grows in moist crevices in Sichuan, it is happy to adapt and is so prolific in flower that I had to find it a place where its early showiness feels right, rather than getting rid of a good plant. More lessons learned, and more to come now that the tide has finally turned.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 April 2018

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage