The first frost of the season came on the night the clocks reverted from summertime. On the still, bright morning that followed, it hung in the hollows, the first fingers of sunshine liberating plumes of mist. We walked down to where they were moving between the yellowed ash and buttery hornbeam to find the leaves falling wet with thaw. Autumn in fast forward now and glorious for it.

Walking back up the ditch to where I had feared the worst for the Gunnera, we found them still standing. Their huge rough leaves had bowed a little, but it was good to find they were still in one piece and that there was time to put them to bed whilst the foliage was intact.

I have a special relationship with these giants, which are splits from a plant I bought with my Saturday earnings, aged ten. The mother plant, which grew in the nearby combe, was a thing of pilgrimage and I would cycle there summer and winter to marvel at its transformation. It sat on a bank where a spring broke to form a little pond at the roadside. In the growing season the water would be all but invisible, dwarfed by the enormous splay of foliage. Broken by winter, a skeleton collapsed and rotting in the water, it struck a sinister mood and I loved it for that.

I wanted to have some really quite badly, to live through the giant’s rise and fall during a year and to grow myself a colony that, one day, I could get lost in. Our thin, acidic sand at the top of the hill was no place for it but, undeterred, I dug a pit and filled it with a plastic liner in readiness. It took a while to pluck up the courage to cycle there with a spade strapped to my bike and to walk up to a stranger’s front door to ask if I could buy some. I remember quite clearly offering the owner a ‘fiver’ and the surprise on his face (it must have been a good sum in the mid ‘70’s) as he said, “Yes. Help yourself !”. I have no recollection of wrestling a growing tip from the mud, but I do recall smiling all the way home with my hard-earned booty strapped to my bike.

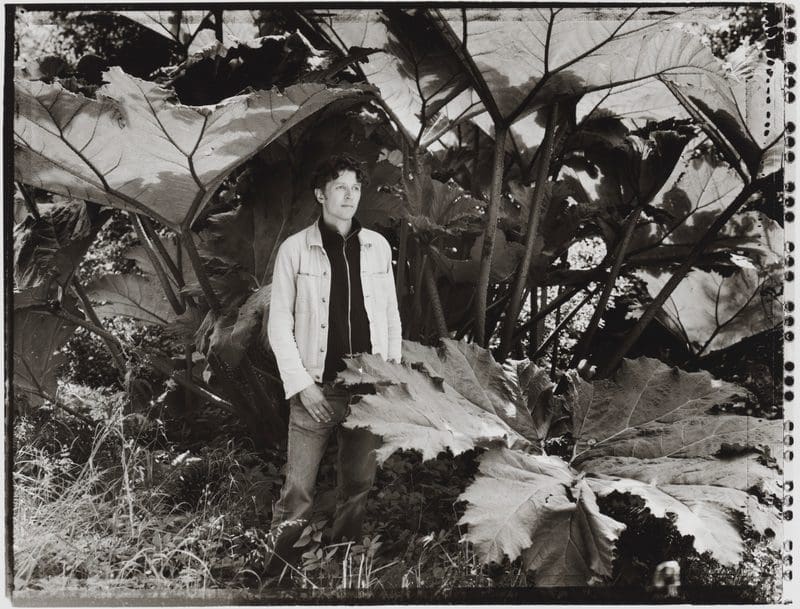

Needless to say, and despite my attentiveness with watering, it didn’t do well until I found it a place in the overflow of the cesspit. Beth Chatto’s advice to “Feed the beast” was my inspiration and, as Gunnera really needs its roots in a steady supply of water, the richness here was the answer. In the years after I left home it grew and it grew and it grew and became quite the focal point in the orchard. Many years later when the photographer, Tessa Traeger, asked me to choose a place that meant something to me for a portrait I asked to be photographed beneath it.

So, after moving here, I was presented with the perfect opportunity to be reunited and relive the drama, the life and death throes of the giant rhubarb. Our wet, oozing ditch and boot-sucking mud where the springs burst from the hillside have made it the perfect home. I have planted about ten offsets which, five years later, are beginning to provide some bulk, since they take a while to settle. A little shelter from the wind provided by the crack willow sees it do best where the plants sit outside the canopy. They grow half as well and rangily in the shadows. Although they should easily double in size with time, the colony is already a place I have dreamed about for some time. A scale change in every way. Somewhere you can walk into and get lost in, the giant parasols throwing a green light as you move amongst them. The prehistoric foliage rasping and textured above you.

Hailing from highlands in Brazil, Gunnera manicata is all but hardy, but it is safest to protect the hoary crowns in winter. Old plants can come through a winter without a cloak of shelter, but two years ago in our heaviest winter here I lost all the main crowns where the frost hung in the hollows. Folding the foliage over the crowns, like a thatch or multi-layered hat is usually sufficient, but until my plants grow strong, they are insulated first with a layer of hay. Cutting the foliage before it is frosted allows for the sturdiest construction and there are few things as satisfying as winter draws close than putting these wigwams together. Protecting the beast for a sure reward once the clocks change again and it stirs from slumber.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 November 2019

Previous

Previous

Next

Next