The old ash pollard on The Tump has now been joined by a number of self-seeded hawthorns

The old ash pollard on The Tump has now been joined by a number of self-seeded hawthorns

One of the ash planted eight years ago on the slopes above the old pollard, the top of which can be seen in the background

One of the ash planted eight years ago on the slopes above the old pollard, the top of which can be seen in the background

Three of the ash planted eight years ago into the hedge on the lane

It was a good plan, or so I thought, to have my hedge trees on a ten year rotation and pollard enough every year to fuel our wood burners. The spectre of ash dieback was first confirmed in the UK just two years later in 2012 and it is now sobering to think how quickly things can change. We discovered the first signs in some seedling trees about three years later and, although none of the trees I planted have been affected yet, my own plans of ash pollards are now in question. And then, as with the disappearance of the elms, there is the visual change we will inevitably see in the landscape, since ash is such a key and widespread component of our woodlands.

The initial panic that circulated in the press soon after the discovery of Chalara eased a little while we waited to see what happened. However, caused as it is by a fungus with wind-borne spores, it has taken only 6 years to become widespread and is now present in most of the country, bar the north of Scotland. What has become clear is that, once a tree is infected, the disease is usually fatal. However, mature trees can survive for some time and during that time they continue to make a valuable contribution to the local ecology and landscape. Ash are also profligate with their seed and scientific study into variability has already shown that a small number of trees are able to tolerate or resist infection.

Hopefully the strong will win out and, with that belief, my plans seem not entirely without hope. But what is becoming increasingly clear is that diversity is important and that no one environment should have all its eggs in the same basket. With this in mind, I have been widening my net and, every year since we came, I have made it a mission to broaden the palette of native trees on the land. There are several projects on the go and winter work includes hedge improvement and extension and the finding of places for long-termers that can step into the fields without making them difficult to manage with machinery.

Three of the ash planted eight years ago into the hedge on the lane

It was a good plan, or so I thought, to have my hedge trees on a ten year rotation and pollard enough every year to fuel our wood burners. The spectre of ash dieback was first confirmed in the UK just two years later in 2012 and it is now sobering to think how quickly things can change. We discovered the first signs in some seedling trees about three years later and, although none of the trees I planted have been affected yet, my own plans of ash pollards are now in question. And then, as with the disappearance of the elms, there is the visual change we will inevitably see in the landscape, since ash is such a key and widespread component of our woodlands.

The initial panic that circulated in the press soon after the discovery of Chalara eased a little while we waited to see what happened. However, caused as it is by a fungus with wind-borne spores, it has taken only 6 years to become widespread and is now present in most of the country, bar the north of Scotland. What has become clear is that, once a tree is infected, the disease is usually fatal. However, mature trees can survive for some time and during that time they continue to make a valuable contribution to the local ecology and landscape. Ash are also profligate with their seed and scientific study into variability has already shown that a small number of trees are able to tolerate or resist infection.

Hopefully the strong will win out and, with that belief, my plans seem not entirely without hope. But what is becoming increasingly clear is that diversity is important and that no one environment should have all its eggs in the same basket. With this in mind, I have been widening my net and, every year since we came, I have made it a mission to broaden the palette of native trees on the land. There are several projects on the go and winter work includes hedge improvement and extension and the finding of places for long-termers that can step into the fields without making them difficult to manage with machinery.

A newly planted oak has a temporary tree guard

A newly planted oak has a temporary tree guard

A gate marker oak planted 4 years ago

Every year I have planted a handful of English oaks (Quercus robur), using them as markers by gates (main image, the large trees are ash) so that you can both locate the breaks in the hedges from a distance and to make a place of the gate; a place to stop in the shade or somewhere for the animals to gather in the heat of the day. Although with climate change there is some speculation as to the long-term suitability of oak in Southern England, my hope is that the combination of our hearty soil and the spring lines that run through the slopes will give them their best chance. Oak has the highest biodiversity count of all native trees and so I am also planning for the life that comes with them.

As gaps have opened up as I upgrade our old hedgelines by stripping them of dominant runs of bramble, elder and old man’s beard, I have been adding common lime to replace the ash should they fail as hedge trees. Tilia x europaea is a beautiful tree if you have the room, not just for its vibrant leaf colour, but for the perfume of the flowers and the benefit these have for the bees and us, as it comes in quantity and makes a delicious tea. Once again, the trees will need extra care and, with this in mind, I made sure they were all planted before the end of the year so that their hair roots can get the best possible chance of being in contact with the soil before the spring. The trees were also given a good mulch of compost to hold in the moisture.

A gate marker oak planted 4 years ago

Every year I have planted a handful of English oaks (Quercus robur), using them as markers by gates (main image, the large trees are ash) so that you can both locate the breaks in the hedges from a distance and to make a place of the gate; a place to stop in the shade or somewhere for the animals to gather in the heat of the day. Although with climate change there is some speculation as to the long-term suitability of oak in Southern England, my hope is that the combination of our hearty soil and the spring lines that run through the slopes will give them their best chance. Oak has the highest biodiversity count of all native trees and so I am also planning for the life that comes with them.

As gaps have opened up as I upgrade our old hedgelines by stripping them of dominant runs of bramble, elder and old man’s beard, I have been adding common lime to replace the ash should they fail as hedge trees. Tilia x europaea is a beautiful tree if you have the room, not just for its vibrant leaf colour, but for the perfume of the flowers and the benefit these have for the bees and us, as it comes in quantity and makes a delicious tea. Once again, the trees will need extra care and, with this in mind, I made sure they were all planted before the end of the year so that their hair roots can get the best possible chance of being in contact with the soil before the spring. The trees were also given a good mulch of compost to hold in the moisture.

One of the new limes planted as hedge trees

Hedge trees are space efficient and their presence along the lanes as another storey above the hedgeline produces protected microclimates and a stillness that harbours insects. The bats run through these fertile air pockets, using them as feeding corridors, as do the birds that benefit from cover from predators. When we first arrived here one of the first things we noticed was the lack of birdlife near the house, with no trees and scalped hedges. We have quickly seen them return, as the trees have risen up to provide shelter, shade and perches for chatter or prey-watching.

One of the new limes planted as hedge trees

Hedge trees are space efficient and their presence along the lanes as another storey above the hedgeline produces protected microclimates and a stillness that harbours insects. The bats run through these fertile air pockets, using them as feeding corridors, as do the birds that benefit from cover from predators. When we first arrived here one of the first things we noticed was the lack of birdlife near the house, with no trees and scalped hedges. We have quickly seen them return, as the trees have risen up to provide shelter, shade and perches for chatter or prey-watching.

Part of the area of hornbeam and hazel coppice on the lower slopes of The Tump above the stream, which were planted 4 and 5 years ago

Part of the area of hornbeam and hazel coppice on the lower slopes of The Tump above the stream, which were planted 4 and 5 years ago

Dan putting tree guards on the newly planted coppice of hazel and sweet chestnut

For the last five years I have been slowly extending a new coppice in the hollow where the field dips away too steeply to the stream edge for haymaking. Thirty trees a year now sees the beginnings of something. Oak, to form a high canopy, and hornbeam and hazel, which will be put on a coppice rotation of twelve and eight to ten years respectively. This year I added some sweet chestnut to see if we can harvest our own poles for fencing in years to come. The coppice will provide the firewood I might be short of should the ash fail, and species variation within it will be good for ringing the changes in the ecology as we work from end to end over the course of a cycle.

It is a good feeling to this year have reached the end of the planted area and to be able to look back from the little whips which have just gone in to the progress mapped in year-on-year growth on the slopes beyond. This next chapter is begun.

Dan putting tree guards on the newly planted coppice of hazel and sweet chestnut

For the last five years I have been slowly extending a new coppice in the hollow where the field dips away too steeply to the stream edge for haymaking. Thirty trees a year now sees the beginnings of something. Oak, to form a high canopy, and hornbeam and hazel, which will be put on a coppice rotation of twelve and eight to ten years respectively. This year I added some sweet chestnut to see if we can harvest our own poles for fencing in years to come. The coppice will provide the firewood I might be short of should the ash fail, and species variation within it will be good for ringing the changes in the ecology as we work from end to end over the course of a cycle.

It is a good feeling to this year have reached the end of the planted area and to be able to look back from the little whips which have just gone in to the progress mapped in year-on-year growth on the slopes beyond. This next chapter is begun.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 January 2019 We have just returned from Greece and a browned and dusty landscape that had not seen water since April. We arrived back to a season changed. Fields deep and lush with grass, hedges flashing autumn colour, dimmed as they reached into a shroud of drizzle. Our distinctive line of beech at the end of the valley all but hidden by cloud and windfalls shadowing the slopes beneath the apple trees in the orchard where, just a fortnight before, the branches had been weighted.

It took a day to retune the eye, but here I sit not a week later with the sun streaming in over my desk and the studio doors wide open to the garden. It is the stillest, most perfect day of autumn and the garden has weathered well. Aged too by the window of time we have been away, but certainly not lesser now that we are in step again with the season.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 January 2019 We have just returned from Greece and a browned and dusty landscape that had not seen water since April. We arrived back to a season changed. Fields deep and lush with grass, hedges flashing autumn colour, dimmed as they reached into a shroud of drizzle. Our distinctive line of beech at the end of the valley all but hidden by cloud and windfalls shadowing the slopes beneath the apple trees in the orchard where, just a fortnight before, the branches had been weighted.

It took a day to retune the eye, but here I sit not a week later with the sun streaming in over my desk and the studio doors wide open to the garden. It is the stillest, most perfect day of autumn and the garden has weathered well. Aged too by the window of time we have been away, but certainly not lesser now that we are in step again with the season.

Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018 We are on holiday for two weeks and so leave you with some recent images of the garden to keep you going until we return.

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’ and Agastache nepetoides

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 October 2018

It has been an extraordinary run. Day after day, it seems, of clear sky and sunlight. I have been up early at five, before the sun has broken over the hill, to catch the awakening. Armed with tea, if I have been patient enough to make myself one before venturing out, my walk takes me to the saddle which rolls over into the garden between our little barn and the house. From here, with the house behind me and the garden beyond, I can take it all in before beginning my circuit of inspection. It is impossible to look at everything, as there are daily changes and you need to be here every day to witness them, but I like to try to complete one lap before the light fingers its way over the hedge. Silently, one shaft at a time, catching the tallest plants first, illuminating clouds of thalictrum and making spears of digitalis surrounded in deep shadow. It is spellbinding. You have to stop for a moment before the light floods in completely as, when you do, you are absolutely there, held in these precious few minutes of perfection.

Now that the planting is ‘finished’, the experience of being in the garden is altogether different. Exactly a year ago the two lower beds were just a few months old and they held our full attention in their infancy. The delight in the new eclipsed all else as the ground started to become what we wanted it to be and not what we had been waiting for during the endless churn of construction. We saw beyond the emptiness of the centre of the garden, which was still waiting to be planted in the autumn. The ideas for this remaining area were still forming, but this year, for the first time, we have something that is beginning to feel complete.

Looking down the central path from the saddle

Looking down the central path from the saddle

The view from the barn verandah

The view from the barn verandah

Of course, a garden is never complete. One of the joys of making and tending one is in the process of working towards a vision, but today, and despite the fact that I am already planning adjustments, I am very happy with where we are. The paths lead through growth to both sides where last year one side gave way to naked ground, and the planting spans the entire canvas provided by the beds. You can feel the volume and the shift in the daily change all around you. It has suddenly become an immersive experience.

An architect I am collaborating with came to see the garden recently and asked immediately, and in analytical fashion, if there was a system to the apparent informality. It was good to have to explain myself and, in doing so without the headset of my detailed, daily inspection, I could express the thinking quite clearly. Working from the outside in was the appropriate place to start, as the past six years has all been about understanding how we sit in the surrounding landscape. So the outer orbit of the cultivated garden has links to the beyond. The Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ on the perimeter skip and jump to join the froth of meadowsweet that has foamed this last fortnight along the descent of the ditch. They form a frayed edge to the garden, rather than the line and division created by a hedge, so that there is flow for the eye between the two worlds. From the outside the willows screen and filter the complexity and colour of the planting on the inside. From within the garden they also connect texturally to the old crack willow, our largest tree, on the far side of the ditch.

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

This first outer ripple of the garden is modulated. It is calm and delicate due to the undercurrent of the Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’, but strong in its simplicity. From a distance colours are smoky mauves, deep pinks and recessive blues, although closer up it is enlivened by the shock of lime green euphorbia, and magenta Geranium psilostemon and Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. Ascending plants such as thalictrum, eupatorium and, later, vernonia, rise tall through the grasses so that the drop of the land is compensated for. These key plants, the ones your eye goes to for their structure, are pulled together by a veil of sanguisorba which allows any strong colour that bolts through their gauzy thimbles to be tempered. Overall the texture of the planting is fine and semi-transparent, so as to blend with the texture of the meadows beyond.

The new planting, the inner ripple that comes closer but not quite up to the house, is the area that was planted last autumn. This is altogether more complex, with stronger, brighter colour so that your eye is held close before being allowed to drift out over the softer colour below. The plants are also more ‘ornamental’ – the outer ripple being their buffer and the house close-by their sanctuary. A little grove of Paeonia delavayi forms an informal gateway as you drop from the saddle onto the central path while, further down the slope a Heptacodium miconioides will eventually form an arch over the steps down to the verandah, where the old hollies stand close by the barn. In time I am hoping this area will benefit from the shade and will one day allow me to plant the things I miss here that like the cool. The black mulberry, planted in the upper stockbeds when we first arrived here, has retained its original position, and is now casting shade of its own. Enough for a pool of early pulmonaria and Tellima grandiflora ‘Purpurteppich’, the best and far better than the ‘Purpurea’ selection. It too has deep, coppery leaves, but the darkness runs up the stems to set off the lime-green bells.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

The newly planted central area

The newly planted central area

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Eryngium eburneum

Eryngium eburneum

There is little shade anywhere else and the higher up the site you go the drier it gets as the soil gets thinner. This is reflected in a palette of silvers and reds with plants that are adapted to the drier conditions. I am having to make shade here with tall perennials such as Aster umbellatus so that the Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which run through the upper bed, do not scorch. Where the soil gets deeper again at the intersection of paths, a stand of Panicum virgatum ’Cloud Nine’ screens this strong colour so it can segue into the violets, purples and blues in the beds below. I have picked up the reds much further down into the garden with fiery Lilium pardalinum. They didn’t flower last year and have not grown as tall as they did in the shelter of our Peckham garden, but standing at shoulder height, they still pack the punch I need.

The central bed, and my favourite at the moment, is detailed more intensely, with finer-leaved plants and elegant spearing forms that rise up vertically so that your eye moves between them easily. Again a lime green undercurrent of Euphorbia ceratocarpa provides a pillowing link throughout and a constant from which the verticals emerge as individuals. Flowering perennials are predominantly white, yellow and brown, with a link made to the hot colours of the upper bed with an undercurrent of pulsating red Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. Though just in their first summer, the Eryngium agavifolium and Eryngium eburneum are already providing the architecture, while the tan spires of Digitalis ferruginea, although short-lived, are reliable in their uprightness.

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

It has been good to have had the pause between planting up the outer beds in spring last year, before planting the central and upper areas in the autumn. We are now seeing the whole garden for the first time as well as the softness and bulk of last year’s planting against the refinement and intensity of the new inner section. Constant looking and responding to how things are doing here is helping this new area to sit, and for it to express its rhythms and moments of surprise.

I am taking note with a critical eye. Will Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ have a stay of execution now that it is protected in the middle of the bed ? Last year, planted by the path, it toppled and split in the slightest wind. Where are the Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Henry Eilers’ and, if they have failed, how will I get them in again next year when everything will be so much bigger ? Have I put too many plants together that come too early ? Too much Cenolophium denudatum, perhaps ? How can this be remedied ? Later flowering asters and perhaps grasses where I need some later gauziness. Will the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri grow strongly enough to provide a highlight above the cenolophium and, if not, where should I put them instead ? The season will soon tell me. The looking and the questioning keep things moving and ensure that the garden will never be complete.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 July 2018

The last few weeks of growth have been remarkable, the volume and intensity lusher for the wet start and the thunderous, still growing weather. In this lead up to summer the garden was texturally wonderful, the layering of foliage acute for the absence or scarcity of flower. Finely divided mounds of sanguisorba, spearing iris and mounding deschampsia all readying themselves, but yet to show colour. A sense of expectation and the build up to the first round of early summer perennials we have today in this posy.

The colour in the garden is designed to come in waves, like a swathe of buttercups in a meadow, that leads your eye from one place to the next and builds in intensity and then dims as the next thing takes over. After an awakening of single peonies, the salvias are the next contrast to the foundation of greens, which I like here for their ease in the landscape. Though I have never found our native Meadow Clary (Salvia pratensis) on the land, it felt right to bring it into the garden in its cultivated form. We have two named varieties which are early to show and good for their verticality. Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, a rich, well-named blue and Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’, which was planted last autumn and is flowering here for the first time this year.

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Where ‘Indigo’ is perfectly named, ‘Lapis Lazuli’ has nothing of the intensity of the stone it is named after, nor of the ultramarine pigment derived from it. I have a nugget on my windowsill which I found once in Greece, sparkling in crystal clear shallows and catching my eye like a magpie’s. Although I was expecting something brighter and cleaner in colour like my find, the clear, soft pink of ‘Lapis Lazuli’ is anything but disappointing. It has been in flower now since early May for a whole three weeks longer than it’s cousin ‘Indigo’, rising up to two feet in widely spaced spires from a rosette of puckered, matt foliage. I expect it to still be looking good at the end of the month, but shortly before it starts to run out of steam, it will be cut to the base to encourage a second flush.

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

The first cut back is always hard, because the salvias are a magnet to moths and bees, but we performed the same severity of cut on ‘Indigo’ last year and it rewarded us with a new foliage and then flower in August. Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, the second of the salvias in this posy and far better named for it’s jewel-like colouring, will also respond to the same treatment, but it is important to act before the energy has gone out of the plant by curtailing its show before it finishes flowering naturally. Energy put into seed will thus be saved and replaced with more flower and the reward of fresh new growth.

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

The cirsium and the cephalaria are also encouraged to produce a second round of foliage by cutting them to the base immediately after they flower. Though they are less inclined to throw out more flower, refreshed foliage is just as useful in an August garden, which needs the greens from this early part of the summer to keep the garden looking lively. The Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ in this bunch grows down by the barns, where its early show coincides with baptisia. Though not remotely blue – a theme that is coming through in this posy, it seems – I love the bluer purple of this form just as much as the garnet red of the Cirsium rivulare ‘Atropurpureum’. These early thistles like plenty of light around their basal clump of foliage and look best for having the air you need to appreciate the way their flowers are held high and free of foliage.

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea is similar in its requirements and looks best when it can punch into air without competition. I grow it as an emergent amongst low Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ at the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido, where they grow ten feet tall on either side of a winding path. The creamy yellow flowers are delightfully sparse and the terminus of a rangy cage of airy growth. Here on our hillside they grow six or seven feet at most and right now appear head and shoulders above their partners. A single plant will leave a sizable hole in a planting if you choose to fell it after flowering, as I do for fresh growth, so it is wise to combine it with later performing partners that ease its temporary absence. Asters, grasses and sanguisorba cover for me here.

I have two more species that are part of the new planting and will flower for me for the first time here this year. Cephalaria alpina is a smaller cousin which is more delicate in all its parts, terminating at about four feet and forming a low mound of divided foliage. Cephalaria dipsacoides, teasle-like in its naming and also in its vertical nature, is up to six feet tall, but grows upright from the base. Creamy in colour like its cousins, but differing from all the plants in this posy in being later to flower and prolifically seeding if it likes you. Although I love its seed heads and the structure they offer the autumn garden, I will be cutting the plants down prematurely before they seed. A practice I am having to employ here with several of the self-seeders, as I do not have the manpower to manage the progeny.

Knautia macedonica

Knautia macedonica

A case in point being Knautia macedonica, that I will now treat as a useful filler where I need something fast and reliable. Our ground is almost too rich for this pioneer and in year two the plants splay fatly where they have been living too well. It too seeds prolifically, and my failure to deadhead them last summer resulted in a rash of seedlings this spring, which showed that it could be a problem if left to go native. A few seedlings on standby, however, will provide me with gap fillers where I need them and a succession of this ruby-red scabious that hovers amongst its neighbours. We pull any pink seedlings, favouring the bloodline of those with darker genes.

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea, the Giant Oat Grass is a plant that I have not grown since Home Farm, where it was a mainstay of the Barn Garden. For a while this grass became so fashionable that I avoided using it, despite its obvious beauty and, without enough room to grow it in the Peckham garden, I gave myself a breather. However, I am very happy to have it back and have given it the room it needs to look its best and for its low mound of evergreen foliage to get the light it needs. Right now it is at its most captivating, the lofty panicles, pale copper before turning gold and heavy with yellow pollen, dancing lightly to catch the long evening light. It is an early grass, bolting sky-bound plumes in May and taking June in a shower of luminosity and light.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 June 2018

Although the snow from last weekend has all but gone, the drifts that stubbornly mark the lee of the hedges on the coldest slopes are a reminder that winter’s grip is still apparent. The primroses, however, have a schedule to keep and have responded with gentle defiance. The first flowers were out just days after the first thaw to light the dark bases of the hedgerows, and now they are set to make this first official week of spring their own.

Since arriving here, we have done our best to increase their domain. Although they stud the cool, steep banks of the lanes, they were all but absent on the land where the cattle had grazed them out. Save for the wet bank above the ditch where they were protected from the animals by a tangle of bramble. We noted that they appeared in this inaccessible crease with ragged robin, angelica and meadowsweet. Four years ago we fenced the ditch along its length to separate the grazing to either side and since then have done nothing more than strim the previous season’s growth in early January to keep the brambles at bay.

Primroses (Primula vulgaris) colonise the banks above the ditch

Primroses (Primula vulgaris) colonise the banks above the ditch

The new regime has seen a slow but gentle shift in favour of increased diversity. Though the brambles had protected them in the shade beneath their thorny cages, now that they have been given headroom the primroses have flourished. Their early start sees them coming to life ahead of their neighbours and, by the time they are plunged once more into the shade of summer growth, they have had the advantage. Four years on we can see them increasing. The mother colonies now strong, hearty and big enough to divide and distinct scatterings of younger plants that have taken in fits and starts where the conditions suit them.

Each year, as soon as we see the flowers going over, we have made a point of dividing a number of the strongest plants. It is easy to tease them from their grip in the moist ground with a fork. However, I always put back a division in exactly the same place, figuring they have thrived in this spot and that it is a good one. A hearty clump will yield ten divisions with ease, and we replant them immediately where it feels like they might take. Though they like the summer shade, the best colonies are where they get the early sunshine, so we have followed their lead and found them homes with similar conditions.

The divisions taken from the heavy wet ground of the ditch have been hugely adaptable. The first, now six years old and planted beneath a high, dry, south-facing hedgerow behind the house, have flourished with the summer shade of the hedge and cover of vegetation once the heat gets in the sun. It is my ambition to stud all the hedgerows where we have now fenced them and they have protection from the sheep. Last year’s divisions, fifty plants worked into the base of the hedge above the garden, have all come back despite a dry spring. Their luminosity, pale and bright in the shadows, will be a good opening chorus in the new garden. The tubular flowers can only be pollinated by insects with a long proboscis, so they make good forage for the first bumblebees, moths and butterflies.

The six year old divisions at the base of the south-facing hedge behind the house

The six year old divisions at the base of the south-facing hedge behind the house

A one year old division at the base of the hedge above the garden

A one year old division at the base of the hedge above the garden

By the time the seed ripens in early summer, the primroses are usually buried beneath cow parsley and nettles, so harvesting is all too easily overlooked. However, last year I remembered and made a point of rootling amongst their leaves to find the ripened pods which are typically drawn back to the earth before dispersing. The seed, which is the size of a pinhead and easily managed, was sown immediately into cells of 50:50 loam and sharp grit to ensure good drainage. The trays were put in a shady corner in the nursery area up by the barns and the seedlings were up and germinating within a matter of weeks. As soon as the puckered first leaves gave away their identity, I remembered that it was a pod of primrose seed that had been my first sowing as a child. Though I cannot have been more than five, I can see the seedlings now, in a pool of dirt at the bottom of a yoghurt pot. The excitement and the immediate recognition that, yes, these were definitely primroses, was just as exciting last summer as it was then.

Primrose seedlings

Primrose seedlings

The young plants will be grown on this summer and planted out this coming autumn with the promise of winter rain to help in their establishment. I will make a point of starting a cycle of sowings so that, every year until I feel they are doing it for themselves, we are introducing them to the places they like to call their own. The sunny slopes under the hawthorns in the blossom wood and the steep banks at the back of the house where it is easy to put your nose into their rosettes and breathe in their delicate perfume. I will plant them with violets and through the snowdrops and Tenby daffodils, sure in the knowledge that, whatever the weather, they will loosen the grip of winter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 March 2018

Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

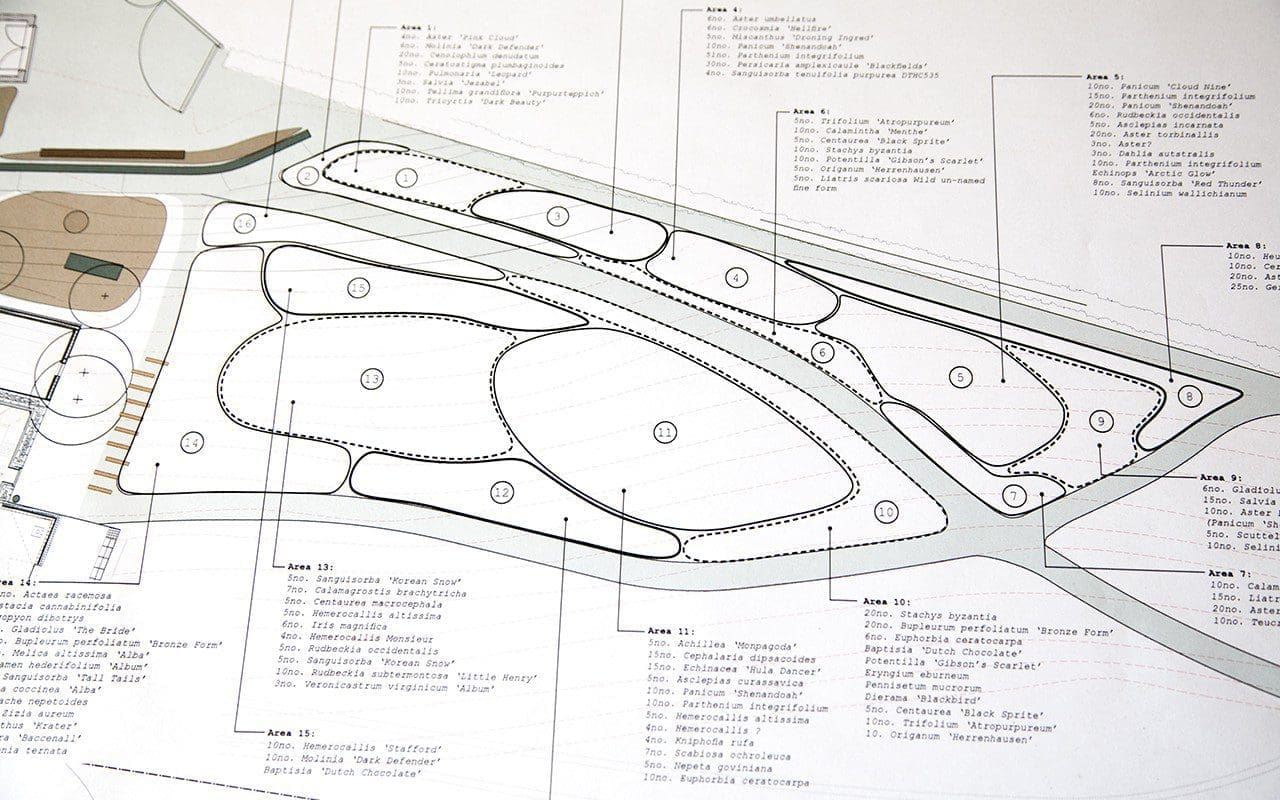

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

I am currently readying myself for the push required to complete the final round of planting in the new garden. The outer wrap went in at the end of March to provide the frame that will feather the garden into the landscape and, with this planting still standing as backdrop, I have been making notes to ensure that the segue into the remaining beds is seamless.

The growing season has revealed the rhythms and the plants that have worked, and the areas where tweaking is required. Whilst there is still colour and volume in the beds I want to be sure that I am making the right moves. The Gaura lindheimerei were only ever intended as a stopgap, providing dependable flower and shelter for slower growing plants. They have done just that, but at points over the summer their growth was too strong and their mood too dominant, going against much of the rest of the planting. This resulted in my cutting several to the base in July to give plants that were in danger of being swamped a chance, and so now they will all be marked for removal. Living fast and dying young is also the nature of the Knautia macedonica and they have also served well in this first growing season. However, their numbers will now be halved if not reduced by two-thirds so that the Molly-the-Witch (Paeonia mlokosewitschii) are given the space they need for this coming year and the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ the breathing room they require now that they have got themselves established.

Gaura lindheimerei

Gaura lindheimerei

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

I will also be removing all of the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ and replacing it with Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. I was so very sure when I had them in the stock beds that both would work in the planting but, once it was used in number, ‘Swirl’ was too dense and heavy with colour. The spires of ‘Dropmore Purple’ have air between them and this is what is needed for the frame of the garden not to be arresting on the eye and so that you can make the connection with softer landscape beyond.

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

As a gauzy link into the surroundings and as a means of blurring the boundary the sanguisorba have been very successful. I trialled a dozen or so in the stock beds to test the ones that would work best here. I have used Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ freely, moving them across the whole of the planting so their veil of tiny drumsticks acts like smoke or a base note. A small number of plants to provide cohesiveness in this outer wrap has been key so that your eye can travel and you only come upon the detail when you move along the paths or stumble upon it. Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, perhaps the best of the lot for its finely divided foliage, picked up where I broke the flow of the ‘Red Thunder’ and, where variation was needed, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ has proved to be tireless. Smattered pinpricks, bright mauve on close examination but thunderous and moody at distance, are right for the feeling I want to create and allow you to look through and beyond.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

The gauze has been broken by plants that draw attention by their colour being brighter or sharper or the flowers larger and allowing your eye to settle. Sanguisorba hakusanensis (raised from seed I brought back from the Tokachi Millennium Forest) with its sugary pink tassels and lush stands of Cirsium canum, pushing violet thistles way over our heads. The planting has been alive with bees all summer, the Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, now on its second round of flower after a July cutback, and the agastache only just dimmed after what must be over three months ablaze. Agastache ‘Blackadder’ is a plant I have grown in clients’ gardens before and found it to be short-lived. If mine fail to come through in the spring, I will replace them regardless of its intolerance to winter wet, as it is worth growing even if it proves to be annual here. Its deep, rich colour has been good from the moment it started flowering in May and, though I can tire of some plants that simply don’t rest, I have not done so here.

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

The lighter flashes of colour amongst the moodiness have been important, providing a lift and the key into the brighter palette in the plantings that will be going in closer to the house in a fortnight. More on that later, but a plant that will jump the path and deserves to do so is the Nepeta govaniana. I failed miserably with this yellow-flowered catmint in our garden in Peckham and all but forgot about it until I re-used it at Lowther Castle where it has thrived in the Cumbrian wet. It appears to like our West Country water too and, though drier here and planted on our bright south facing slopes, it has been a truimph this summer.

Nearly all the flowers in the planting here are chosen for their wilding quality and the airiness in the nepeta is good too, making it a fine companion. I have it with creamy Selinum wallichianum, which has taken August and particularly September by storm. It is also good with the Euphorbia wallichii below it, which has flowered almost constantly since April, the sprays dimming as they have aged, but never showing any signs of flagging.

Nepeta govaniana

Nepeta govaniana

Selinum wallichianum

Selinum wallichianum

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

I have rather fallen for the catmints in the last year and been very successful in increasing Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ from cuttings from my original stock plant. I plan to use the softness of this upright catmint with the Rosa glauca that step through the beds to provide another smoky foil.

Jumping the path and appearing again in the planting that will be going in in a fortnight are more of the Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’. True to its specific name, this pretty, white calamint seems happy to seed around in cool places and I have used it, as I have the Eurybia diviricata, as a pale and cohesive undercurrent. They weave their way through taller groupings to provide an understory of lightness, breathing spaces and bridges. Both of these are on the autumn order and will jump again into the new palette I have assembled to provide a connection between the two.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 October 2017

The new planting went in on the spring equinox, a week that saw the energy in the young plants shifting. Just seven days later the emerging fans of the hemerocallis were already splayed and flushed, and the signs were also there in the tightly-clasped crowns of the sanguisorba. The chosen few from my trial in the stock beds had to be split to make up the numbers I needed, but energy was on their side and, once in their new home, they seized life quickly to push new foliage.

We mulched the beds immediately after planting to keep the ground clean and to hold in the moisture whist the plants were establishing. Mulching saves so much time in weeding whilst a garden is young and there is more soil than knit of growth. This year I was also thankful because we went into five long weeks without rain. I watered just once, so that the roots would travel down in search of water, but once only so that they did not become reliant. The mulch held this moisture in the ground and the contrast to the old stock beds that went without has been is remarkable. Spring divisions that went without mulch have put on half as much growth and have needed twice as much water to get the same purchase. I can see the rigour of my Wisley training in this last paragraph, but good habits die as hard as bad ones.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

17 June 2017

17 June 2017

Since it rained three weeks ago, the growth has burgeoned. As the summer solstice approaches the dots of newly planted green that initially hugged the contours of our slopes have become three dimensional as they have reared up and away into early summer. I have been keeping close vigil as the new bedfellows have begun to show their form, noting the new combinations and rhythms in the planting. Information that I’d had to hold in my head while laying out the hundreds of dormant plants and which, to my relief, is beginning to play out as I’d imagined.

14 May 2017

14 May 2017

16 June 2017

16 June 2017

Of course, there are gaps where I am waiting for plants that were not then available, and also where there were gaps in my thinking. There are combinations that I can see need another layer of interest, and places where the plants are already showing me where they prefer to be. The same plant thriving in the dip of a hollow, but not on a rise, or vice versa. Plants have a way of letting you know pretty quickly what they like. At the moment I am just observing and not reacting immediately because, as soon as the foliage touches, the community will begin to work as one, creating its own microclimate that will in turn provide influence and shelter. I lost my whole batch of Milium effusum ‘Aureum’, which I put down to the exposure on our south-facing slopes. However, most of them have managed to set seed, so I am hoping that next spring the seedlings will find their favoured positions to thrive in the shade of larger, more established perennials.

The wrap of weed-suppressing symphytum that I planted along the boundary fence is already knitting together, and I’m happy to have this buffer of evergreen foliage to help prevent the landscape from seeding in. However, a flotilla of dandelion seed sailed over the defence and are now germinating in the mulch. We saw them parachuting past one dry, breezy day in April as if seeking out this perfect seedbed. They are easy to weed before they get their taproot down and will be less of a problem this time next year when there will be the shade of foliage, but they will be a devil if they seed into the crowns of plants before they are established. A community of cover is what I am aiming for, so that the garden starts to work with me, and time spent protecting it now is time well spent.

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, Nepeta subsessilis ‘Washfield’, Viola cornuta ‘Alba’ & Knautia macedonica

The comfrey is planted in three drifts. Symphytum grandiflorum, S. ‘Hidcote Blue’ and S. g. ‘Sky Blue Pink’. The latter is new to me and I’m watching carefully that they aren’t too vigorous. I’ll have to keep an eye on the next ripple of plants that are feathered into the comfrey from deeper into the garden as the symphytum can also be an aggressive companion. The Sanguisorba hakusanensis should be able to hold their own, as they form a lush mound of foliage, and the Epilobium angustifolium ‘Album’ should be fine, punching through to take their own space. I’ll clear the young runners where the creep of the comfrey meets the gentler anemone and veronicastrum.

The ascendant plants were placed first when laying out and will form a skyline of towers through which the other layers wander. They are already standing tall and providing the planting with a sense of depth. Thalictrum ‘Elin’ is my height already, a smoky presence of foliage and stems picking up the grey in the young Rosa glauca and proving, so far, to not need staking. This is important, because our windy hillside provides its challenges on this front. Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ has also provided immediate impact, its limbs inky dark and the mauve of the flowers giving early colour and contrast to the clear, clean blue of the Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’. Next year the garden will have knitted together so that the contrasts will work against foliage or each other, but for now the eye naturally focuses not on the gappiness, but where things are beginning to show promise.

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

Thalictrum aquilegifolium ‘Black Stockings’ with Iris sibirica ‘Papillon’ behind

There have been a couple of surprises already, with a fortuitous mix up at the nursery reavealing a new combination I had not planned for with a drift of Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’ coming up as S. nemorosa ‘Amethyst’. I am very particular about my choices and I’d planned for ‘Indigo’ since growing it in the stockbeds, but the unexpected arrival of ‘Amethyst’ has, after my initial perplexity, been a delight. I’ve not grown it before, and I like its earliness in the planting and how it contrasts with the clear blue of the Iris sibirica with a little friction that makes the eye react more definitely than with the blue of ‘Indigo’. I like a little contrast to keep zest in a planting. The Euphorbia cornigera, with their acid green flowering bracts, are also great for this reason with the first magenta of the Geranium psilostemon.

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ and Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

Thalictrum rochebrunianum with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’ behind

As the last few plants that weren’t ready in the nursery become available, I’m wading back into the beds again to find the markers I left there when setting out so that I can trace my original thinking. I am pleased to have done this, because it is very easy to start to reshuffle, but the original thinking is where cohesiveness is to be found. Changes will come later, after I’ve had a summer to observe and see where the planting is lacking or needing another seasonal lift. I can already see the original perennial angelica has doubled in diameter, and I’ve added eight new seedlings which, if left, will be far too many so a few removals will be necessary comer the autumn. Patience will be the making of this coming growing season, followed by action once I can see my plans emerging.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 June 2017

This year we have based ourselves here for three full weeks to see out the last of December and welcome in the new year. Your eye is free to travel further in this wintry landscape and it has been good to follow by venturing beyond our boundaries. Slowly – for it took a few days to get into the routine of it – a walk has started the day. We have been both up and down the valley and high onto the exposed ground of Freezing Hill to experience the roar of the wind in the beeches and to understand why it has its name, as it whips up the slopes that run down the other side to Bristol. Always looking back to see how we fit into the folds, we have contributed to our knowledge of muddy ways, well-worn tracks, breaks in hedges and crossing points back and forth across the ditches and streams. Marking our way – for nearly every field has at least one – are the ancient ash pollards.

Ash wood burns green so the trees have value and owning enough pollards would keep you in firewood if you attended to them in rotation. The pollards regenerate easily from cuts made above the grazing line, so that they can grow away again unhindered by the cattle. Usually standing solitary on a steeply sloping pasture (where they add to their usefulness by providing summer shade for livestock) the pollards are stunted by decades of decapitation and, in combination, make an extraordinary trail of characters in the landscape.

We have stopped at each one to take in their histories and their winter slumbers that expose their distinct personalities. Some are hollow to the core, the new limbs surviving on little more than a thin rim of bark. Inside the hollows map the decay and hold the damp and the smell of it even in the dry months. The halo of new growth that breaks from the old forms a crown of fresh limbs that in ten or twelve years are big enough for harvesting. To date the cycle has continued until the trees are exhausted and split and fail.

Of course, we are waiting patiently to see if the pollards survive the chalara dieback that is moving across the country and is already in the valley. Neighbours who have lived here a lifetime recount how different the landscape was when the elms rose up in the hedgerows, but it is the ash and their potential demise that will now be cause for a new perspective.

The solitary ash pollard on The Tump

The solitary ash pollard on The Tump

We have a solitary pollard on the west facing slopes of The Tump. The farmer who lived here before us climbed the tree to harvest the wood in the year he died. The tree must have been huge once, the trunk striking the form of an imposing female torso. An interesting presence given the fact that the ash was once seen as the feminine counterpart to the father tree, the oak. When we arrived here there was just a summer’s regrowth and I set to immediately planting thirty new ash in the hedgerows to provide us with our own rotation. So far – and I remain hopeful – they have done well, despite our mother tree showing a reluctance to throw out another set of limbs and the forecasts that estimate a five percent survival for ash in this country.

We have let the grass grow long on the slopes that are too steep for haymaking around our pollard and in six years there are the beginnings of a new habitat. An elder has sprung from high in her crown and a black and sinister fungus from the side that has refused to regrow branches. Around her there is a skirt of bramble and young hawthorns where the birds have previously settled in her branches and stopped to poop. I plan to plant an oak I grew from an acorn amongst them. New life around the old and a suitable partner, I hope, for a changeable future.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage