This time last week we were still reeling from the excitement and stimulation of the first Beth Chatto Symposium. Originally intended to celebrate Beth’s 95th birthday this year, following her death in May the event became both a memorial to her and a celebration of her influence on a generation of gardeners, designers and nurseries, both here and overseas.

The symposium was the idea of Amy Sanderson, a Canadian gardener and florist who has spent some time working at the Beth Chatto Gardens in recent years, and was organised by Amy, Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg. When the symposium was announced early this year they anticipated in the region of 150 attendees, and so were thrilled when over 500 people from 26 countries bought tickets. Åsa told me that they could have sold many more.

The theme of the symposium was Ecological Planting in the 21st Century, and the line-up of international speakers included gardeners, garden designers, academics, nursery-people and growers, all with their own take on the subject, although a number of key themes became apparent over the two days. The talks were recorded and will be posted on the symposium website as soon as they have been edited.

In the main image above are, from left to right, James Hitchmough, Dave Ward, Taylor Johnston, Olivier Filippi, Marina Christopher, Peter Janke, Dan Pearson, Midori Shintani, Keith Wiley, Andi Pettis, Peter Korn, Åsa Gregers-Warg, Cassian Schmidt and Amy Sanderson.

James Hitchmough

James Hitchmough

Opening and closing the symposium were presentations by James Hitchmough, Professor of Horticultural Ecology in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Sheffield. James has done a huge amount of research into seeded naturalistic plantings over the past 30 years and, as an academic and researcher, was generous and instructive in the information he shared. He was very clear in communicating the ecological value and function of designed landscapes, but explained that the highest value and most stable functioning of a planting is achieved through its ability to persist – its longevity. This is directly linked to biomass, since the denser a planting is both above and below ground, the less unwelcome weed species are able to invade it. The layering of foliage above ground, from groundcovers through to tall emergents, also shades out weed species, creating a more stable planting. He advised that the biggest challenge in dynamic naturalistic plantings is identifying what they are to become and how to manage them with this guiding vision in mind. All of these observations rang true.

Keith Wiley

Keith Wiley

All of the speakers spoke about the inspiration they have taken from observing native plants in the wild, and both Keith Wiley and Peter Korn spoke passionately about their travels to Crete and South Africa, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and North America, respectively as being hugely influential on the ambitious private gardens they have both created in Devon and Sweden. Keith was, for 25 years, the gardener at The Garden House at Buckland Monachorum, one of the most influential gardens of the 1990’s in bringing naturalistic planting to the attention of a wider audience. His talk focussed on the aesthetic possibilities of combining plants as they appear in nature, and he illustrated it with lush images of highly colourful, exuberant plantings.

Peter Korn

Peter Korn

Peter explained the challenges he had set himself by wanting to grow as wide a range of dry-climate plants as possible from all over the world, in an inhospitable climate and with the added difficulty of high rainfall and sub-zero winter temperatures. Both explained in detail the lengths they had gone to in order to create specific microclimates and soil conditions to allow them to grow some of their favourite species. Of great interest was Peter’s method of growing plants in deep sand, which both encourages the formation of stronger mychorrhizal communities and presents a hostile environment for self-seeding weeds.

Cassian Schmidt

Cassian Schmidt

Similarly, Professor Cassian Schmidt, Director of Hermannshof Garden described the creation of a large number of habitat types to showcase a wide range of plants in this public garden located in Weinheim, near Heidelberg. Originally based on the ecological principles of Professor Richard Hansen, Hermannshof now has in excess of 18 habitat areas from North American Prairie to East Asian Woodland Margin and European Dry Steppe. In tune with James Hitchmough, Cassian also described the importance of plant ‘sociability’ when planning plantings, choosing plants with compatible growth habits and cultural requirements to build persistent, self-regulating communities. His experiments with dense plant layering, and the use of primroses as an early-season, weed-supressing groundcover encouraged us in our own thoughts about these as a means of closing the ecological gap in our own plantings.

Peter Janke

Peter Janke

Fellow German, nurseryman and garden designer, Peter Janke, worked at the Beth Chatto Gardens as a young man in his 20’s, and was hugely inspired by Beth’s experiments and success in the Gravel Garden. After returning home he introduced her teaching of using plants best suited to the habitat conditions in one’s garden to an audience of German gardeners. Peter spoke about the challenges posed by the recent high summer temperatures, which have been especially extreme where he lives in central Germany, and described how he created his own garden, based on many of Beth’s planting principles, in particular a gravel garden of his own, which has performed remarkably well this year.

Olivier Filippi

Olivier Filippi

French nurseryman, Olivier Filippi, spoke passionately about planting palettes for Mediterranean and dry landscape plantings, the development of which he is at the forefront of, supplying projects all over the mediterranean. Although many of the speakers talked of striking a balance between aesthetics and function, Olivier was very clear that, in a dry climate, a functional landscape is, by necessity, a beautiful one. He described the use of cushion-forming, evergreen sub-shrubs as key in his work, and flower as the least important aspect in making plant choices, leading to an appreciation of the ‘black and white garden’ where rhythm, form, texture and contrast are the primary considerations. He also spoke vigorously about the need for water conservation and encouraged the audience to regard maintenance as one of the most enjoyable parts of gardening. He was also dismissive of current trends for using only native species in plantings, arguing that, in relation to the scales of planetary time and geographical change, such a stance was limiting and myopic.

Andi Pettis

Andi Pettis

As a complete contrast Andi Pettis, Director of Horticulture at The High Line, spoke of the very particular challenges of gardening in an extreme urban environment. As well as the technical and organisational difficulties of maintaining a podium garden high above the ground. She also focussed on the relationship between the public and plants, and the fact that people are also a part of landscapes and their associated ecosystems, whether natural or designed. Like Cassian Schmidt she also spoke passionately about the educational benefit of a public park where horticulture is paramount, and how, even in the centre of one of the busiest cities in the world, it is possible to get people to engage with and appreciate natural cycles and rhythms and ecology.

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan had also been invited to speak, and he did so primarily about his work at the Tokachi Millennium Forest, although he too illustrated the fundamental impact that Beth Chatto had had on his early understanding of plant habitat requirements, and the importance of creating planting schemes that are culturally balanced and in context with their surroundings.

His talk was followed by one given by the Head Gardener at the Millennium Forest, Midori Shintani, and her first public presentation in English. Midori talked of the ancient Japanese belief in animism, the power of all natural things, of the landscape, and of nature worship. She also explained the importance of satoyama, the term used to describe the territory formed by the intimate relationship between man and the productive agricultural landscape at the boundary of the wild. These ideas were then developed as she explained how she and her team of gardeners approach the work of maintaining, not just the designed landscapes at this public park in Hokkaido, but the very forest itself. She spoke beautifully and with great tenderness about the fact that everything is connected, and the importance of taking great care and making close observation of natural processes. She expressed the deep interconnections between people, landscapes, natural habitats, plants and fauna with immense simplicity and lightly worn wisdom. It was no surprise to find that, as she delivered her final words and the hall filled with applause, many in the audience were crying.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 September 2018

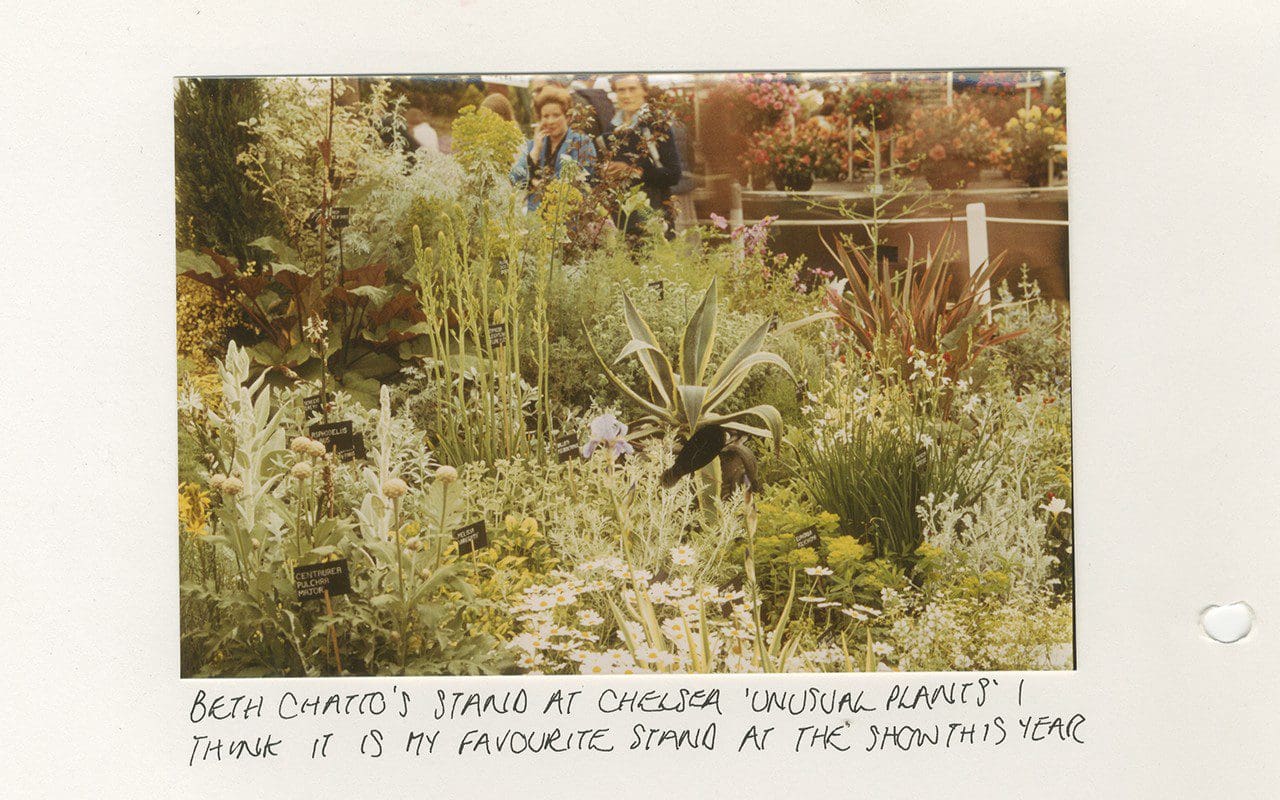

I first encountered Beth Chatto in 1977 at The Chelsea Flower Show. It was the first time she had exhibited and, aged 13, it was also the first time I’d attended the show. I remember quite distinctly the spell that was cast when my father and I came upon her stand. The froth, confection and sheer horticultural bravado that made the show remarkable fell into the background, and suddenly everything was quietened as we stood there, entranced.

We worked the four sides of the display, noting the differences between the plants that were grouped according to their cultural requirements. Leafy woodlanders cooled the mood where they were mingled together, with barely a flower, in celebration of a green tapestry. Nearby, and separated by plants that allowed the horticultural transition, were the delicate blooms of the Cotswold verbascums, ascending through molinias and sun-loving salvias. Plants with none of the pomp of the neighbouring soaring delphiniums, but which were captivating for their modesty and feeling of rightness in combination. The exhibit stood apart and was confidently delicate. We learned from it, filling notebooks hungrily with sensible combinations, happy in the knowledge that the wild aesthetic we were drawn to was something attainable.

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

At that point no one else was doing what Beth was doing and, when I met Frances Mossman, who commissioned me to make my first garden five years later, it was those show stands that brought us together. We talked at length about Beth’s ethos, the excitement of combing her catalogues of beautifully penned descriptions and our resulting purchases.

Of Crambe maritima, she wrote, “Adds style and grandeur to the filigree grey and silver plants. Waving, sea-blue and waxen, the leaves alone can dominate the border edge, while the short stout stems carry generous heads of creamy-white flowers in early summer. The stems are delicious, blanched in early spring, served as a vegetable. 61 cm.”

While Gladiolus papilio is, “Strangely seductive in late summer and autumn. Above narrow, grey-green blade-shaped leaves stand tall stems carrying downcast heads. The slender buds and backs of petals are bruise-shades of green, cream and slate-purple. Inside creamy hearts shelter blue anthers while the lower lip petal is feathered and marked with an ‘eye’ in purple and greenish-yellow, like the wing of a butterfly. It increases freely. Needs warm well-drained soil. 91 cm.”

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima

Crambe maritima

We came to rely upon her nursery of then ‘unusual plants’; me with a long border I had planted in my parents’ garden, and Frances with her own first garden in Putney. Unusual Plants was the place we would go to help us make that first garden together and, when we started making the garden at Home Farm in 1987, it was Frances who wrote to Beth to tell her of her positive influence and of what we were doing there to make a garden without boundaries. Beth wrote back with careful responses and encouragement. Once I had got over my shyness, I too started to write and we struck up a friendship from which I will always draw inspiration and refer back to as pivotal in my own development.

Beth made an indelible impression with her words, wisdom and practical application of good horticulture. In this country she was arguably the link back to the beginnings of William Robinson’s naturalistic movement and an informality that drew inspiration from nature. Her writings were always dependable and combined the artistry of an accomplished planting designer with the fundamental practicality of someone who had seen how plants grew in the wild and knew how to grow them to best effect in combination in a garden.

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

If you study Chelsea today, it is easy to overlook the influence she had on the industry of nurserymen and designers. The ‘unusual plants’ that were her palette are no longer so, and the way in which they were combined naturalistically on her stands has become the status quo. Rare now are the perfect bolts of upright lupins and highly-bred, colourful perennials, not so the mingled informality of plants that are closely allied to the native species, many of which had their origins at her nursery.

Though we will all miss her presence after her sad departure last weekend, her influence will remain strong. In the hands of Beth’s trusted team, led by Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg, the gardens and nursery have never been better. In recent years, as Beth’s health has deteriorated, Julia Boulton, her granddaughter, has firmly taken the reins and, as well as ensuring that the gardens and nursery continue into the future, has been responsible for setting up the Beth Chatto Education Trust and, this year, a naturalistic planting symposium in her name which takes place in August. At its heart the gardens will become a teaching centre, a living illustration of Beth’s passion for plants and her ecological approach to gardening.

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

Looking around my garden this morning, I can see Beth’s influence almost everywhere in the plants that are grouped according to their cultural requirements. Be it the ‘pioneers’ in the ditch, which have to battle with the natives, or the colonies of self-seeders I’ve set loose in the rubble by the barns, her teachings and plant choices are everywhere. Her plants also connect me to a wider gardening fraternity, a reminder of her generosity and willingness to share. The Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum that has seeded itself around the vegetable garden was first given to me by Fergus Garrett as ‘Beth’s Poppy’, since she had passed on the seed, while the Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ growing against the breezeblock wall by our barns, was collected by her great friend, the artist and aesthete, who helped open her eyes to the beauty of plants.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

A visit to the nursery is still one of my favourite outings. I can guarantee quality and know that I will find something that I have just seen growing right there in the garden and have yet to try for myself. About twelve years ago, on a trip that culminated in a full notebook and an equally full trolley, Beth gave me a plant of Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’ accompanied with the usual words of good advice about its cultivation. Sure enough, it is a good plant both in its ability to perform and in terms of its elegance. I moved it carefully from the garden in Peckham and divided it the autumn before last to step out in an informal grouping in the new garden. Last Sunday, although I did not know that this was the day she would finally leave us, the first flower of the season opened. As is the way with a plant that has a heritage, I spent a little time with her, pondering aesthetics and practicalities. I know for certain that it will not be my last conversation with Beth.

Beth Chatto 27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 May 2018

The various utensils, paper bags and home-made envelopes that have been accumulating all summer were grouped together recently for examination. I find it hard to resist when seed is there for the taking and it is something that I want or could do with more of. If I am lucky and have had a pen handy, the makeshift envelopes are scrawled with notes to make identification easy. The unmarked vessels might need a rattle and a closer look to remind me, but the excitement of a haul usually burns the find into the memory, as long as I act before winter blurs the clarity of this past growing season.

Fortuitously, autumn is the best time to sow the hardy plants and I would rather have them in the cold frame, labelled up and ready to go than degrading and waiting until the spring. In the wild, seed will start its cycle within the same growing season, so emulating the natural rhythm makes perfect sense. Most seed will now sit through the winter to have dormancy triggered by the stratification of frost, but some will seize the damp and comparative mild of autumn to germinate before winter and begin their grip on life.

The giant fennel are a good example. In the Mediterranean and Middle East where they are dependent upon the winter rainfall for growth, summer-strewn seed is now germinating with the first rains. My own sowings from August have already produced their second true leaf and are now potted on in long toms so that they can continue to establish their strong tap roots in the mild periods ahead of us. The winter green of Ferula communis (main image) is remarkable for this late season regeneration, gathering strength when it isn’t too cold and pushing against the general retreat elsewhere.

Sowing seed of Ferula communis in Autumn

Sowing seed of Ferula communis in Autumn

Seedlings of August’s sowing of Ferula communis in the cold frame

Seedlings of August’s sowing of Ferula communis in the cold frame

I first saw giant fennel in my early twenties when I was a student at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens. Michael Avishai, the Director, had driven me to the Golan Heights to see them in the minefields where they grew freely and undisturbed. We stood at the roadside, taking heed of the sign saying ‘DANGER MINES! Go no further.’ Mile upon mile of cordoned-off ground, back-dropped by the mountains of Syria, was populated by a legion of uprights which bolted skyward in a scoring of perfect verticals. You understood why the Romans had used them as ferules, their stems making a lightweight measuring rod. Amongst their feathery mounds of basal foliage, a flood of acid-green euphorbia and scarlet anemone scattered the rocky ground between them.

You need open ground and the room to be able to let giant fennel have its reign in the garden. Whilst the plants are gathering strength, the early foliage needs the air and light they are accustomed to. Once they have bolted all their energy into the lofty flower stem, the foliage withers to leave a space, so you need to plan for a companion such as Ballota pseudodictamnus that can take a little early shade, but will cover for the gap in high summer.

I first flowered Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ in my garden in Peckham and brought seed from there to here. It is the first of several giant fennels to have flowered here and did so in its third year after planting out. This lustrous form of the Tangier fennel is spectacular for its early growth, which is as shiny as patent leather, but finely-cut like lace. The flowering stem, which is shorter than F. communis, which can grow to 3 metres, holds an inflorescence that is just as flamboyant, despite reaching just half that height. My plants originally came from Beth Chatto where it appears in her gravel garden and this is how they like to live, with guaranteed good drainage in winter. I mean to ask if she was given the plant by the great man himself, for I am amassing quite a number of his selections and enjoy the connection of these horticultural hand-me-downs.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ flowering in late May

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ flowering in late May

Coincidentally, I was given a brown paper bag with ‘Ferula tingitana blood’ scrawled on it by one of the gardeners from Great Dixter at a lecture that I gave for the Beth Chatto Education Trust earlier this summer. It is one of several ferula that Fergus Garret has passed on to me over the years. He too is under their spell and has given me seed of several of his wild collections from his homeland in Turkey. Once, when I asked him what the mother plant was like, he said, ‘No idea. It’s bound to be good though. Try it !’. And with giant fennels I am very happy to take him on trust.

Fergus uses them as punctuation marks in the garden where they bolt above moon daisies and rear over the hedges like giraffes. They have started to hybridise there and, when they are established enough to plant out next spring, the ‘tingitana blood’ seedlings are destined for my new planting. The secret to growing them successfully is to plant them out before the long tap roots wind around the pot for, to support the huge flowering stem, they need their purchase deep in the ground like a skyscraper needs its footings.

A hatful Ferula communis seed gathered in Greece

A hatful Ferula communis seed gathered in Greece

This summer, whilst on holiday in the Dodecanese, I collected a hatful of Ferula communis that had flowered beside the road and somehow escaped the ravages of the island goats. Though I had not seen it in flower, it was impossible to pass it by and the thought of it reappearing as a memory in the garden here will allow me to relive this find when it comes to flower. The seed left after my own sowing is now sitting in a bag waiting to go to Fergus, with a scrawled message of well wishes and the happy thought that they will soon be on their way to another good home.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan & Dan Pearson

Published 7 October 2017

Last Friday I was honoured to speak at the University of Essex in support of The Beth Chatto Education Trust, of which I am a patron. My brief, to talk about the importance of education in horticulture, was an easy one to meet and that much more relevant with the Trust firmly up and running. Julia Boulton, Beth’s granddaughter and Managing Director of the Gardens and Director of the Trust, has made it her mission to utilise the garden as an educational resource and it was with much excitement that we met to celebrate the fact that the garden now has this important new future.

Beth Chatto (centre front) with behind (left to right) Dave Ward, Garden Director, Julia Boulton, Managing Director, Dan Pearson, Karalyn Foord, Education Trust Manager and Åsa Gregers-Warg, Head Gardener

Beth Chatto (centre front) with behind (left to right) Dave Ward, Garden Director, Julia Boulton, Managing Director, Dan Pearson, Karalyn Foord, Education Trust Manager and Åsa Gregers-Warg, Head Gardener

Beth’s work has always been important and the garden is as relevant today as it ever has been. At the forefront of the naturalistic movement in this country, and instrumental in originating the ethos of ‘the right plant in the right place’, Beth’s displays at The Chelsea Flower Show were ground breaking in the 1970’s. I remember their singularity, for no one else at the show was using the plants that she was cultivating or combining them as intelligently; plants that were wild in feeling, always close to the species and grouped according to their habitat needs, not the whim of colour themes or border compositions. Apparently, in the early days, some show judges are said to have dismissed her displays as being nothing more than cultivated weeds, but the message to gardeners was strong, practical and consistent; put a plant where it wants to be and it will thrive. It is barely credible now that this approach should have been seen as unusual, but in the days of annual bedding, hybrid tea roses and prize dahlias Beth’s was a shock doctrine.

And she was far more than simply the nurserywoman who presented her wares at the show. You could also depend upon her not only for her impeccable taste, but also for her ability to educate you through her plantsmanship. For years Unusual Plants was the only place to go to get the plants I wanted to grow and I pored over the evocative descriptions in the catalogue. My borders in my parents’ garden were stocked with her treasures and it was through a love of her plants that I bonded with my first client, Frances Mossman, with whom I created the gardens at Home Farm. We had both fallen under the spell of Beth’s catalogue and I remember very clearly a key conversation about Beth’s description of Crambe maritima. A seaside wilding brought to life and into horticultural focus through words. A world of opportunity that was suddenly possible once you made the connections. When I started travelling to see native plants growing in the Himalayas, Israel and Europe in my ’20’s Beth’s ethos was plainly articulated in every plant community I saw and helped me make the connections between the wild and the cultivated.

Earlier last Friday, before the talk, we took a tour of the gardens with Dave Ward, the Garden Director and long term member of the team. At the Gravel Garden (main image) we stopped to catch up with Beth, who had come out to greet us and marvel at the Romneya. Just two days after celebrating her 94th birthday she had lost none of her fervour for the importance of horticulture and was vocal about how good education and competitive salaries are essential to encourage young people into the profession. It was so good to see her in her environment and I remembered how she had once talked about being in New Zealand with Christopher Lloyd and had dreamed of making this garden after they had come across a dried up river bed.

Repeated Genista aetnensis set the mood, its peppered clouds of gold, luminous against the dark hedges. Nothing looked out of place, with all the plants chosen for their drought resistance and moving about in the gravel as if they had found their way there and their companions quite naturally.

Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’ and Stipa gigantea

Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’ and Stipa gigantea

A repeat of vertical verbascum to arrest the eye; Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, dull white and caught in a gauze of Stipa gigantea, with a smattering of pink Dianthus carthusianorum. Felted Verbascum bombyciferum standing alone and breaking free at the very edges of the planting. Romneya coulteri fluttering close to the path so that you could inspect the boss of golden stamens. A stand of Stipa barbata given their own space and floating like seaweed in the breeze.

The feathered seedheads of Stipa barbata with Verbascum bombyciferum and Romneya coulteri against the hedge

The feathered seedheads of Stipa barbata with Verbascum bombyciferum and Romneya coulteri against the hedge

There were many plants that I am using at home which Beth introduced me to as a child (Eryngium giganteum, Lychnis coronaria, Crambe maritima, Romneya coulteri, Stipa gigantea, Dianthus carthusianorum, Phlomis russelliana) and others that I have come to from other directions, but surely because of Beth’s influence. An acid-yellow mist of Bupleurum falcatum through which the dark orbs of Allium sphaerocephalon were suspended. Buttons of pale yellow Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, hunkered down and throwing off light. Splashes of electric-blue Eryngium x zabelii, metallic and architecturally jagged amongst the softness.

Allium sphaerocephalon, Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, Bupleurum falcatum and Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’

Allium sphaerocephalon, Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, Bupleurum falcatum and Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’

Eryngium x zabelii with Bupleurum falcatum

Eryngium x zabelii with Bupleurum falcatum

We moved from there into the lower sections of the garden where the compositions were driven by green and texture. Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg reminded us of Beth’s love of ikebana and the asymmetric triangle that repeats in her compositions. Watery reflections, plants adapted to their foothold, be it edge of the dry oak woodland or spearing Thalia dealbata amongst scale changing Alisma plantago-aquatica in the shallows of the ponds. Splashes of fiery candelabra primula amongst green umbrellas of Darmera peltata and in a narrowing on the way to the Reservoir Garden, the oversized creamy plates of Sambucus canadensis ‘Maxima’, a plant that I haven’t grown since I was a teenager. On enquiring about its availability (I had the nursery set firmly in my mind as a highlight of the day) Dave tipped me off. “You can get that at Great Dixter.” More connections from my early education. A plant I had all but forgotten about but, all these years later, am just as excited to be revisiting.

The Water Garden

The Water Garden

Alisma plantago-aquatica with foliage of Thalia dealbata on the right

Alisma plantago-aquatica with foliage of Thalia dealbata on the right

The best gardens are all about connections and the garden here at Elmstead Market is full of them. Talk to Beth and she will very quickly tell you about the importance of her husband, Andrew’s work as a botanist in identifying plants from all over the world that had the ability to grow together. She will tell you too about her friendship with Cedric Morris, and you will find his collections and selections in the garden if you dig a little and ask the right questions.

My notebook filled rapidly – the nine foot Allium ‘Purple Drummer’ and Agastache ‘Blue Boa’ amongst Deschampsia caespitosa ‘Schottland’ – and it continued to do so in the nursery where we had a behind the scenes look at the industry of the place and saw at close quarters all those treasures that have gone out into the world to fuel passions. My order of new-to-me and untested plants came together without hesitation. Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Schottland’, Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’, Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’, Salvia verticillata ‘Hannay’s Blue’ and Teucrium hircanicum to name a handful. They have just arrived, within the week, beautifully packaged as ever, bringing all the excitement that has been coming to me from this inspirational place for the best part of forty years.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 July 2017

The Woodland Garden

The Woodland Garden