In March, the week after my mum died, we received an email from Simon Bray, a Manchester-based photographer and artist, asking if we might be interested in featuring him and a new book he was self-publishing. The book, Signs of Spring, is a collection of family photographs he has assembled of his childhood garden, which was initiated in part by the death of his father, and the importance the garden had in Simon’s memories of him. Although it was pure coincidence that Simon chose to write that week, it felt as though I was being offered an opportunity to remember mum in a new way. The more of Simon’s work I saw, the stronger this feeling became.

Simon, can you tell us how you came to study and work with photography ?

I began taking photographs when I moved to Manchester from Winchester for university. It was quite a shift for me, having lived in rural Hampshire my whole life, so I would walk everywhere, exploring the city by foot. Taking pictures helped me assimilate. I’ve never actually studied photography. I studied music, but as a drummer, so taking photos was something I could do on my own without requiring others and the practicalities that come with playing drums! Photography became one of many ways in which I like to express myself creatively and I’m now very fortunate to call it my job, making time for both artistic projects and commercial work.

You have a clear interest in place as a locus for memory. How did you come to realise and key in to this aspect of photography ? Has the idea of loss always been intrinsic to your work, or is it something that has developed over time ?

The notion of place has always been central to my practice. As I mentioned, Manchester was a starting point, but photographing places such as The Lake District helped me to understand that there was something about taking photographs in certain locations that excited me and made it easier to express myself. This has led me to explore my own connections to physical places and also work with others to explore theirs. It’s not always somewhere grand and romantic like the lakes, the garden from my family home has probably been the most significant place in my life and where I took many photographs.

The notion of loss came into my work after my dad passed away in December 2009. It took me quite a while to pick up my camera after that, nothing seemed significant enough to make pictures of but, over time, I began to appreciate that my photography could actually be hugely beneficial in helping me to express how I was feeling.

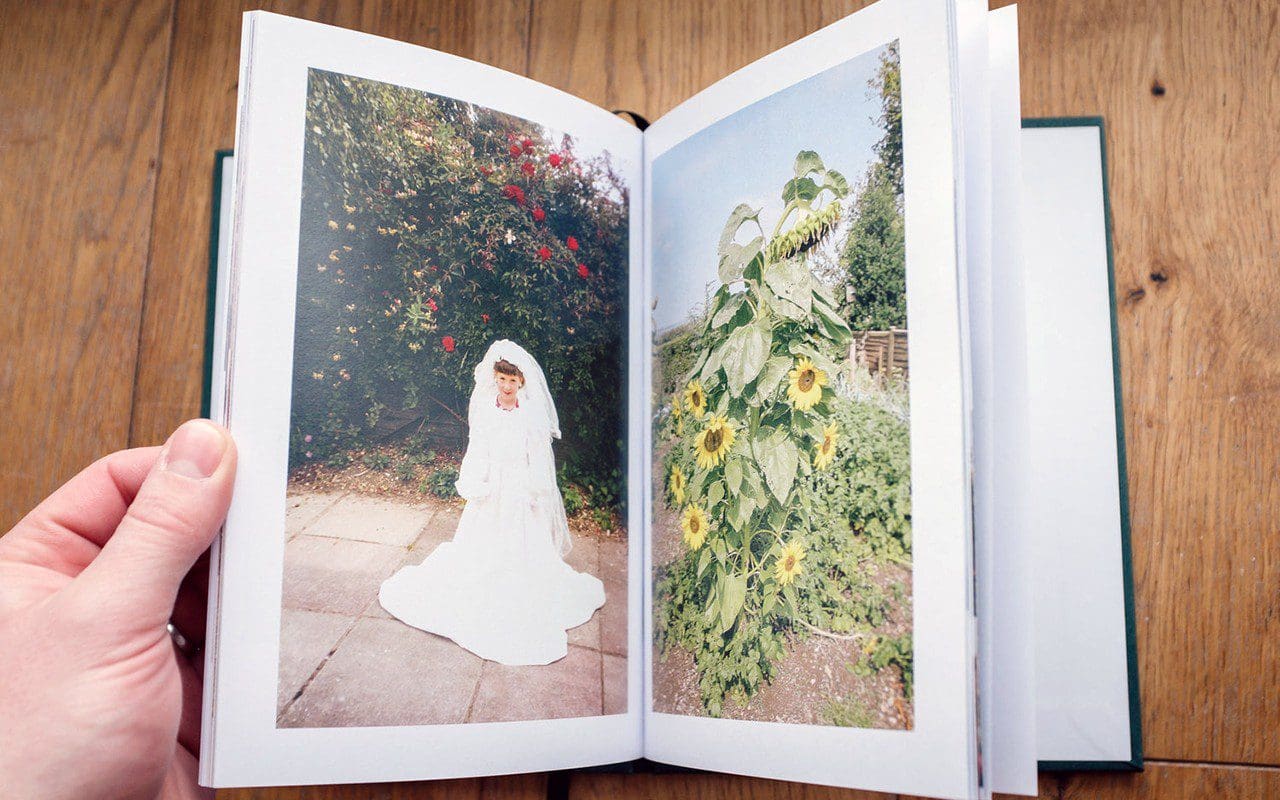

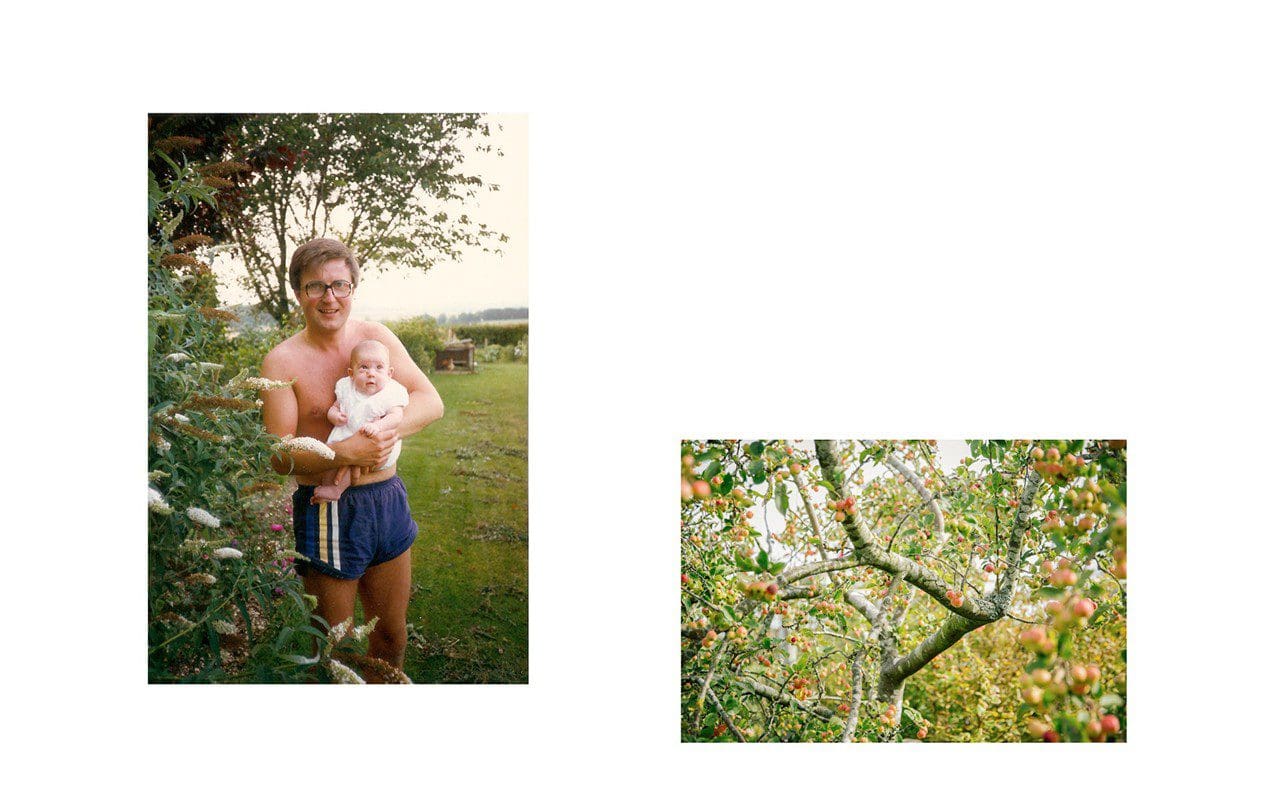

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

I was really moved by Signs of Spring, the book you have published in memory of your dad. Also your ongoing photography project 30th December which is also connected to memories of your father. Can you tell me how each of these projects came about, what they mean to you and what they provide for you ?

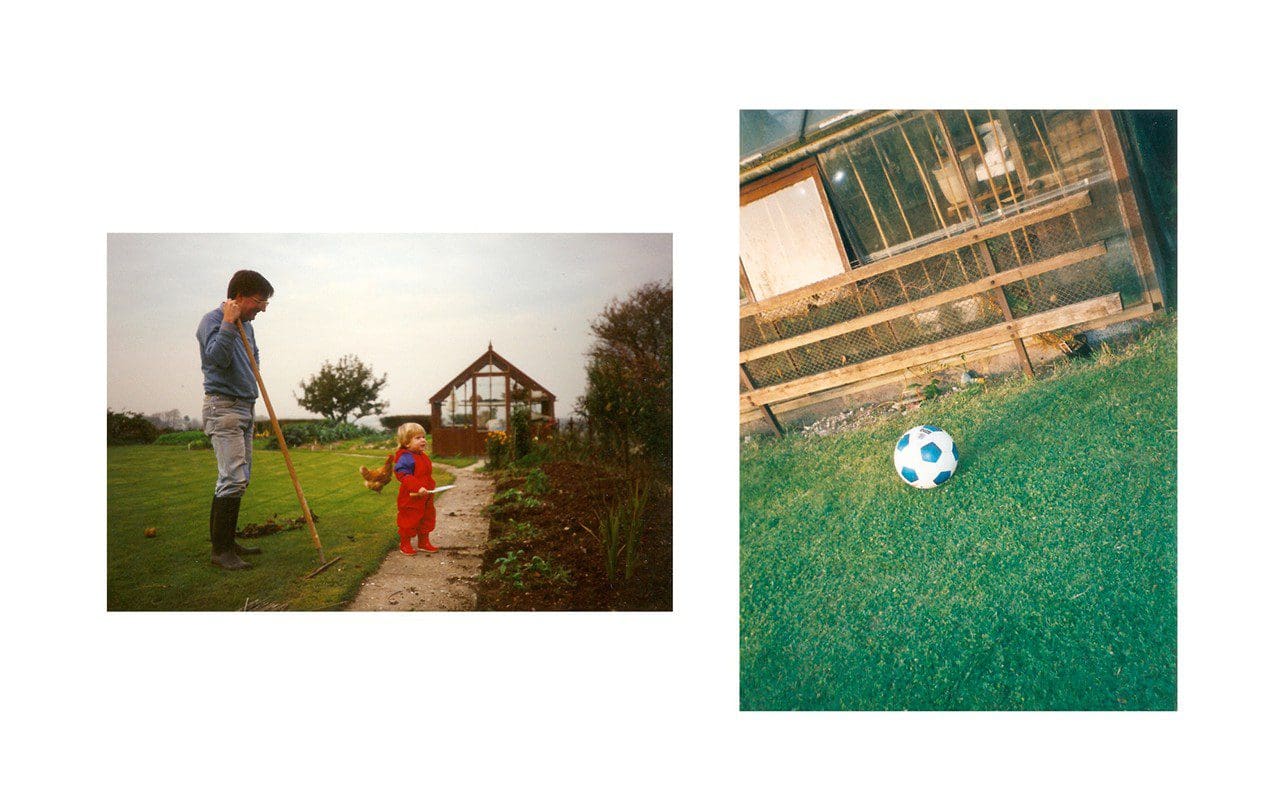

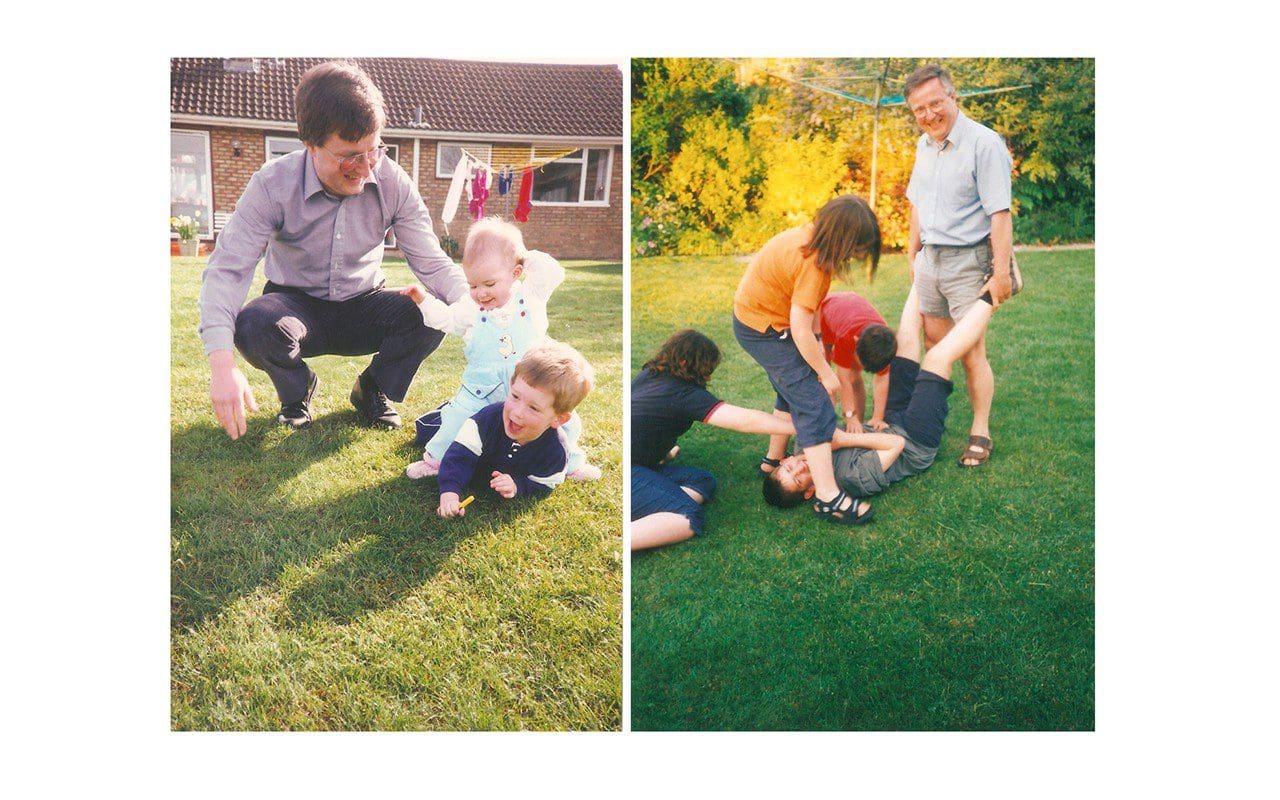

Both of those projects are about place, memory and loss, manifested in different ways. Signs of Spring is a collection of photographs that I’ve gathered together, found in family photo albums. It’s not a memorial as such, more a celebration of the life of our family in the garden where I grew up. Dad was a very keen gardener, having grown up on a farm in Cornwall he spent every hour of a daylight outside, producing vegetables and fruit and keeping everything very well maintained. It was a playground for my sister and I and the location for countless family occasions, so it holds many special memories for me. After dad passed away, mum vowed to keep the garden going, which she did very well, continuing to produce fruit and veg, but a couple of years ago she decided it was time for a fresh start and moved down to Penzance. That meant having to say goodbye to the house and garden I’d grown up in, which was far harder than I’d imagined. It felt like having to let go of Dad all over again, so I wanted to celebrate the garden by producing this book.

The 30th December project is very similar actually. It’s the anniversary of dad’s passing and, once I’d picked up my camera again, on each anniversary I’d go out and make pictures. Last year I made a series of handmade books with photographs taken at dawn on St. Catherine’s Hill in Winchester, somewhere we used to go as a family. The pictures aren’t necessarily about loss, they’re not inherently sad pictures, but it’s a process that helps me remember and engage with how I’m feeling on that day. I shall keep on making photographs on 30th December each year, wherever I am in the world.

Photographs from 30th December

Photographs from 30th December

I am interested in how you see gardens as a receptacle for childhood and family memories. Can you tell us your thoughts about this and how gardens differ from other landscapes, both urban or rural ?

Unless you’re a farmer, your garden is a patch of the world that you’ve been gifted to take care of. You can do with it as you please, you can pave it over and not have to think about it, or you can cultivate it to feed your family, create a place to relax and share with others, or fill it with flowers for others to see and enjoy. There’s something very satisfying about a well-maintained front garden! It’s the sense of ownership and responsibility that makes it differ from urban and rural spaces, not that you can’t feel ownership of the town you live in or your favourite national park, but those are shared spaces, your approach differs to that of your own garden. I’ve recently moved to my first house that has a garden and I’m getting so much pleasure from looking after it. Simply just staring out the window at the birds feeding as I write this is making me feel relaxed!

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

The Loved&Lost project looks at a wide variety of places through the prism of loss, memory and the passing of time. I found it very cathartic reading about other people’s experience of losing a loved one. Can you tell me more about how the project came about and what you learnt from it ?

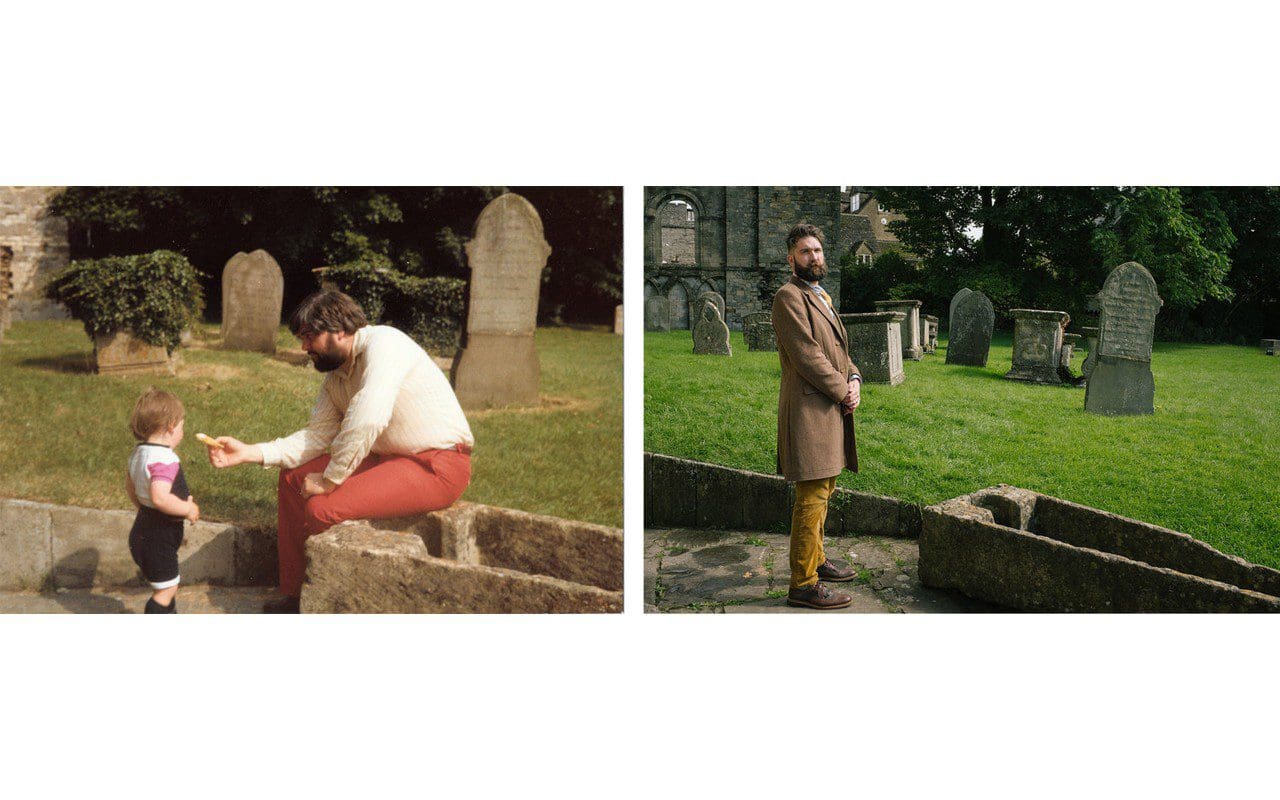

As I alluded to earlier, after the loss of my father I found ways to try and help others engage with their loss, and this now manifests itself as the Loved&Lost project. I invite participants to find a family photograph of themselves with somebody who is no longer with us, we then return to the location of the photograph to re-stage it and record a conversation about the day. It’s amazing how impacting it is to return to the physical location of the photograph. It brings back so many memories and makes it all very tangible for the participant. I want to encourage them to engage with their loss in a different way. The photograph is simply a starting point, but the process allows us to have a conversation, to recall the day the first image was taken, to share their account of losing someone close to them, but also celebrate the person who is no longer here.

When dad passed away, lots of people asked me how I was, which is a very kind and natural thing to do, but in the mix of it all, I didn’t actually know the answer to the question and so I didn’t really want to talk about me, what I wanted to talk about was dad. I found myself in social situations recalling memories, jokes, anecdotes that he would have enjoyed, but not really being able to share them because there was no context for everyone else, so I wanted to create a forum in which it’s absolutely fine to share your favourite stories about that person that no-one else knew quite like you did.

The project is ongoing, and I learn something new from every person I meet. It’s not about having to be strong or getting over it after a certain amount of time – some people take part months after their loss, others many many years – the loss is still there, but how you engage with it varies. Lots of people end up restructuring their lives after a significant loss, your focus changes and priorities get realigned, it shapes you, not always in ways that you understand in the moment, but over time I find that most people feel it’s important to know that some good has come out of their pain, and for me, I’d like to think that Loved&Lost is that.

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

Much of your landscape photography has a very particular atmosphere of emptiness or vacancy, like stage sets where the protagonist has just left or is just about to arrive. Can you explain your feelings about ‘wild’ landscapes and how we relate to and inhabit these environments ?

I really like that analogy, because as much as the landscapes within the UK especially can be wild, most of them are fairly approachable as well. Obviously you need to be cautious and equipped according to the weather, but there are so many accessible and varied locations within these British Isles that can be truly breathtaking. So many of us use the outdoors as a means of escape. I will always feel better about life if I’ve spent the day outside, particularly in some mountains or by water, so it feels very natural to be drawn towards that as subject matter photographically. I quite intentionally don’t include people within my landscape photographs. In fact, sometimes there’s not much of anything in my work, probably just sky and mist with a bit of land at the bottom of the frame! I think that’s a result of my yearning for space. My mind seems to be full of thoughts and ideas all the time and stretching my legs and exploring somewhere new seems to not necessarily turn that off, but brings clarity and energises me mentally. The space required for that comes through in my images, which sometimes can appear bleak or vacant, but I suppose it’s a thoughtfulness or consideration that gets subconsciously built into the photographs.

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

How did the The Edges of These Isles project come about and how did you collaborate with artist Tom Musgrove on it ?

Working with Tom came about after we did the Three Peaks Challenge together with a couple of friends. We established that we’d both like to be making more work inspired by landscape and that it would be very interesting to see how a painter and a photographer might be able to collaborate. It took us a couple of years, but we ventured all across the UK together, making work, sharing thoughts, ideas, music and establishing where our approaches to making work could meet and where they differed. We ended up making a 120 page book, a 25 minute film and have exhibited the work 3 times. It was a huge step forward in terms of my appreciation of what it means to be an artist and how I can engage with the subject matter before me and utilise it to express myself. The work I made on those trips is still some of my favourite that I’ve created. I’m a romantic at heart, so the aesthetic and notion of the sublime are very much in my mind when I’m working within the landscape, but I also want to bring myself into the image. I like to do my best to avoid making pictures that I know have been captured countless times before by awakening my senses in that moment to really understand how I’m going to make that picture, which is something I learnt from Tom.

What can you tell me about your involvement with One Of Two Stories, Or Both (Field Bagatelles), the piece by Samson Young that was commissioned for the 2017 Manchester International Festival ?

I was fortunate to be selected as one of six artists to take part in a fellowship with Manchester International Festival last year. This involved being placed within one of the festival commissions and I was very lucky to work with Samson Young, who had just represented Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale. It was incredible to see him at work, creating a 5 part radio play complete with live musicians, voice actors and foley artists, as well as constructing an installation for the Centre For Chinese Contemporary Art in Manchester. He invited me to play drums in the radio pieces and make a photograph for the installation, both of which were a huge privilege. I also got to engage with the other young artists and experience many other performances within the festival, which really broadened my horizons in terms of what I create and who my audience is. Not that I have the answers for those things yet, but it was a hugely inspiring experience.

Samson’s piece was all about the hypothetical journey of Chinese migrants to Europe at the start of the century travelling by train. It was amazing to observe how Samson created that world through the medium of radio, utilising the music, actors and created sounds. It formed amazing visual landscapes in my mind and really informed how I engaged with the characters in the piece. It got me thinking about how I construct the landscape images that I make, how much of it is me simply photographing what’s in front of me, and to what extent do I build the feel and atmosphere of an image in how I shoot and edit it.

Photographs from The Edges of These Isles

You are currently working with Martin Parr on a new commission for Manchester Art Gallery. Firstly, I’d love to hear your take on Martin’s photography and what it means to you. Then can you then tell me anything about the work you’re collaborating on?

Martin was one of the first photographers I was ever made aware of, and there’s something about his style which is so stark, but so honest at the same time and his sense of humour is something I know I’ve tried to seek out in my street photography work as well. I’ll see one of his images and know straight away that it’s his, which, as a photographer, is something I’ll always be aspiring to.

I began working with Martin in March as the producer for his commission with Manchester Art Gallery for an exhibition opening this November. The gallery is going to show a huge selection of Martin’s Manchester work from the past 40 years, from when he studied here in the early 70’s up until today, which is what we’re currently working on now. So I’m spending a lot of time arranging shoots, but then I get to work alongside Martin for a few days at a time and it’s a real privilege to observe him working, he’s so confident and assured, just being around him for a few days fills me with confidence.

And finally, what are you working on personally at the moment, and are there any opportunities for us to see your work anywhere ?

I have a couple of exhibitions coming up, the first is Duality, a documentary project that I’ve collaborated on with another Manchester photographer. Its focus is workwear and uniform, posing questions about how we perceive the individual based on their appearance, which they potentially haven’t chosen for themselves, but also how the individual perceives themselves based on what they’re wearing. That’s going to be on show at The Sharp Project, Manchester on 31st May.

I’m also showing a selection of stories from Loved&Lost at Oriel Colwyn in Colwyn Bay throughout July. It’s the first time the work will have been shown in a gallery, so I’m currently establishing how to do that sensitively and effectively.

Working with Martin and finishing off the Loved&Lost stories is keeping me fairly busy at the moment, but I have begun work on a couple of new projects, one inspired by the locations that feature in Brian Eno’s album Ambient 4 : On Land, and the other is about photographing smells, which I know is impossible, but I’ve just started developing the idea to see if it’ll work!

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs: Simon Bray

Previous

Previous

Next

Next