Marcin Rusak is a London-based Polish designer who explores themes of consumption, ephemerality, aging, decay and longevity in his work. For very personal reasons he has chosen to work with flowers in a range of different ways. I recently met him at his new studio where he talked to me about his history, his process and his creations.

Tell me how you arrived at this way of working with flowers.

It was quite an adventure for me to get into the Royal College of Art. It started with me studying European Studies, not liking it, doing interior design on the side and trying to get into art school in Poland. They didn’t accept me. So I tried the Design Academy Eindhoven, the conceptual design school, not knowing at all what conceptual design is. I was supposed to be there for four years, but after two I felt I wanted to experience more, and the way Dutch education works is they wipe your head clean and they inject their tools into you and after four years you’re only allowed to use those tools. So after years of study I knew that I wanted something more. I wanted freedom, so that’s where the RCA came into the picture.

At the RCA you’ve got this amazing ability to make mistakes all the time, and find your own thing. So I found my own thing through an accident again, because there was a brief to find an object that interests you, like from your past or wherever, just something that you like.

And so I found this cabinet that we had in my family house, which was from the 17th century. It’s a Dutch cabinet, and it’s carved in wood, and the whole sculptural decoration is inspired by nature and the seasons. So I just started investigating, ‘Why is it that I like it so much ?’. So the first natural step for me was to go and investigate nature and flowers – the subjects of the carvings – and I went to a flower market for the first time. And that’s where I started seeing all this waste. And because I was always interested in processes, I took the waste material and started doing everything I possibly could with it, to get somewhere, not really knowing where it was going. And that’s how I discovered printing with flowers.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

On your website there is a video of you making one of these textiles. What is the liquid you were spraying on the flowers ?

Vinegar. It helps to bring out the natural pigments in the flowers, and it also helps them to penetrate the silk. I also use special silks made specifically for digital printing, because they are treated with substances which react with ink, and although the flower pigments are not inks the silk reacts in the same way and the pigments become more light fast. When I first tried with normal silk the colour only lasted about a month. These pieces are about a year old and have not really faded that much, but they will fade eventually, although they will never completely disappear. I still have all the ones I made, as it is really hard to sell things that don’t last, but people have started to understand me better now, and they are prepared to buy the idea along with the object. Also recording the process of making the work becomes part of the work itself.

By the end of this project I went to my tutor, and I said, ‘You know what? It’s actually really funny that I’m doing these things with flowers now, because I have a history of 100 years of flower growing in my family.’

When I was born the business was closing down, so maybe about two or three years after I was born it closed. So until I was 26 and at the RCA I really had nothing to do with flowers.

I was raised in those abandoned glasshouses. That was my childhood playground. It was amazing. I still have this memory of the very dry warmth when you were in the glasshouses, but there was nothing else, just these pipes coming out from everywhere, and all these steel structures, but no flowers, no natural material. And then we moved when I was 10. My mum always loved flowers and she always wanted to do something with them, but she never did.

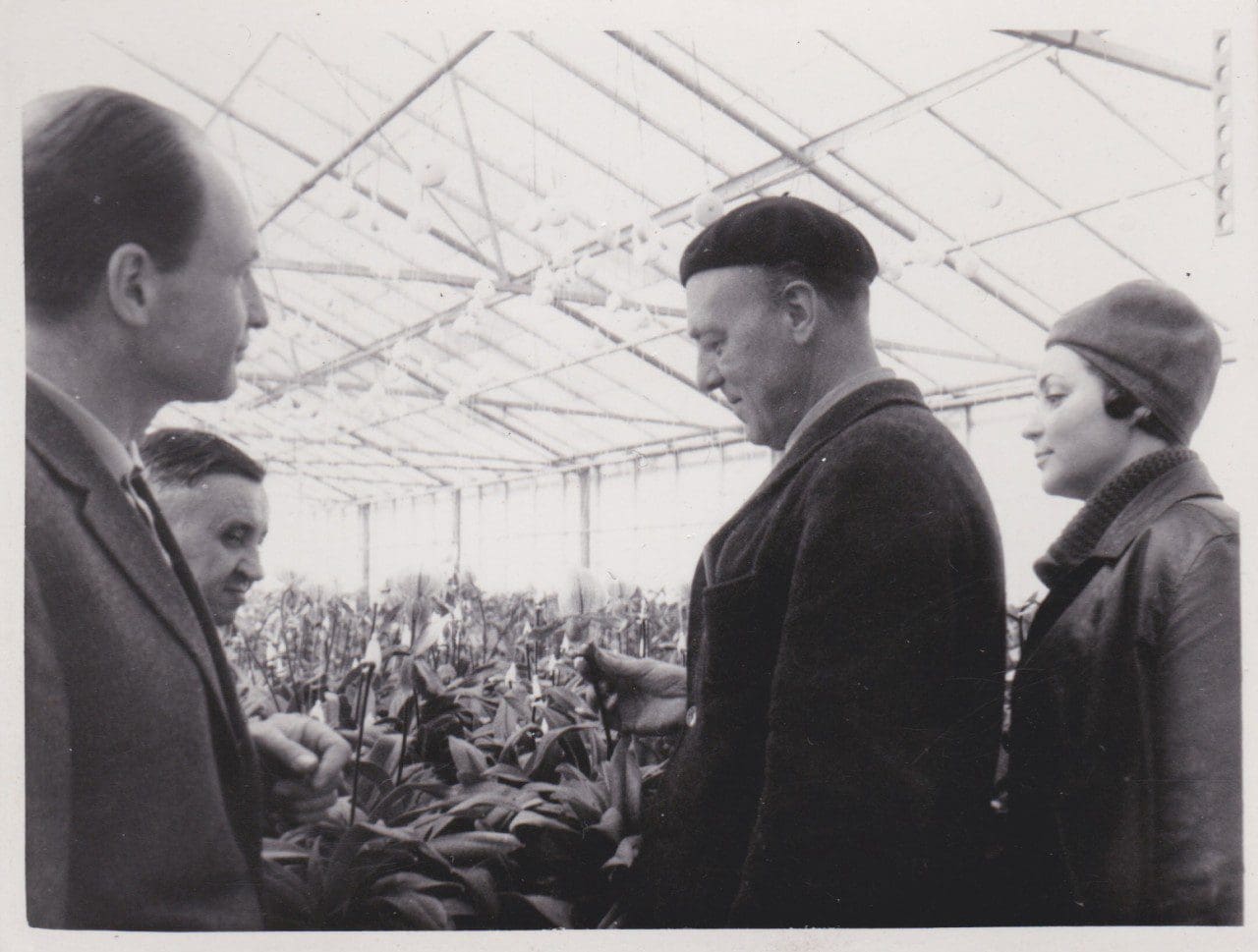

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So the flowers weren’t really in the family, they were in this amazing history we had, because my grandfather, and his father, for over a hundred years they were growing flowers. They also had flower stores, so they had a really big business, mostly growing orchids. And my grandfather was kind of a freako scientist, so he was really bad with people, but amazing with plants. So actually discovering this was a breakthrough for me, but it was also quite natural. Although I kill plants, or I use dead plants or I make objects that die !

But it made me think. I remember having this conversation at the RCA with one of the tutors, they asked, ‘Why are you doing this, actually ? It’s nice that its this textile that extends the life of already dead flowers by months or years, so that’s great, but what’s the interest ? Think about it. Why ?’

So then I started doing much more research work in the Netherlands and actually trying to understand why people manipulate flowers so much these days, and how flowers became a commodity, and how they are being sold in Tesco and grown in Kenya, and flown with planes and using water in places that don’t have water. All of the background of what people don’t know about commercial flower growing. And then I started explaining to people that it’s a bit like the food industry, that started to change 10 years ago, when we started realising how we source food and intensively farm it and so on and so on. So I established a connection with Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, right next to the massive flower market there. And I made a book about it.

So you got into the science of flowers through doing this book, which you hadn’t really thought about before ?

No completely not! Because, you know, like a lot of people I just didn’t know what the situation was with flowers being grown, because we don’t have to eat them, so we don’t really think of them in the same way that we think of food, because in a way, they are perceived as a luxury. So I started investigating it at the university and they helped me a lot. At the beginning they were very suspicious of what I was doing, because they work with a lot of big brands which pay a lot of money to get their research and I was going in there saying ‘Hey, can you tell me about this ?’ for nothing. But I established a nice connection and they let me see a few things and we started talking and I introduced to them to the idea of the flower monster that I wanted to do, which is basically combining everything we want from flowers today. From retailers, to growers and consumers, everyone wants flowers to be a certain way, either living longer or smelling better or being cheaper to ship. And in the end they should be this natural imperfection, and not manipulated so much, so for me it was interesting to think about how to put that all into one piece and start communicating it to people and make them aware.

So the idea was to create this flower that does it all. So if we play with the DNA, and if the industry keeps on going the way it is right now where we keep manipulating things, it is where we might end up. I first started talking to plant geneticists to try to understand about breeding and cross-breeding, because it is possible to cross-breed a lily with a bamboo and so on. So if you have a lily which has a stem with genes from a bamboo it can then stand on a strong stem and hold this whole creature up. But how do we get there physically ? How do we make it happen ? So we researched the plants that have the certain characteristics that we needed, so anthuriums are very light, so transportation would be easier, and bamboo for the stem, or orchids with their roots outside the plant which could transport nutrition, so the whole thing could live for months. So I started working with Dutch flower engineer Andreas Verheijen, who agreed to help me with the project, and we basically took the plant species, cut them up and put them together them as nature might. Then it was flown to London in a day. It was the weirdest thing I ever did.

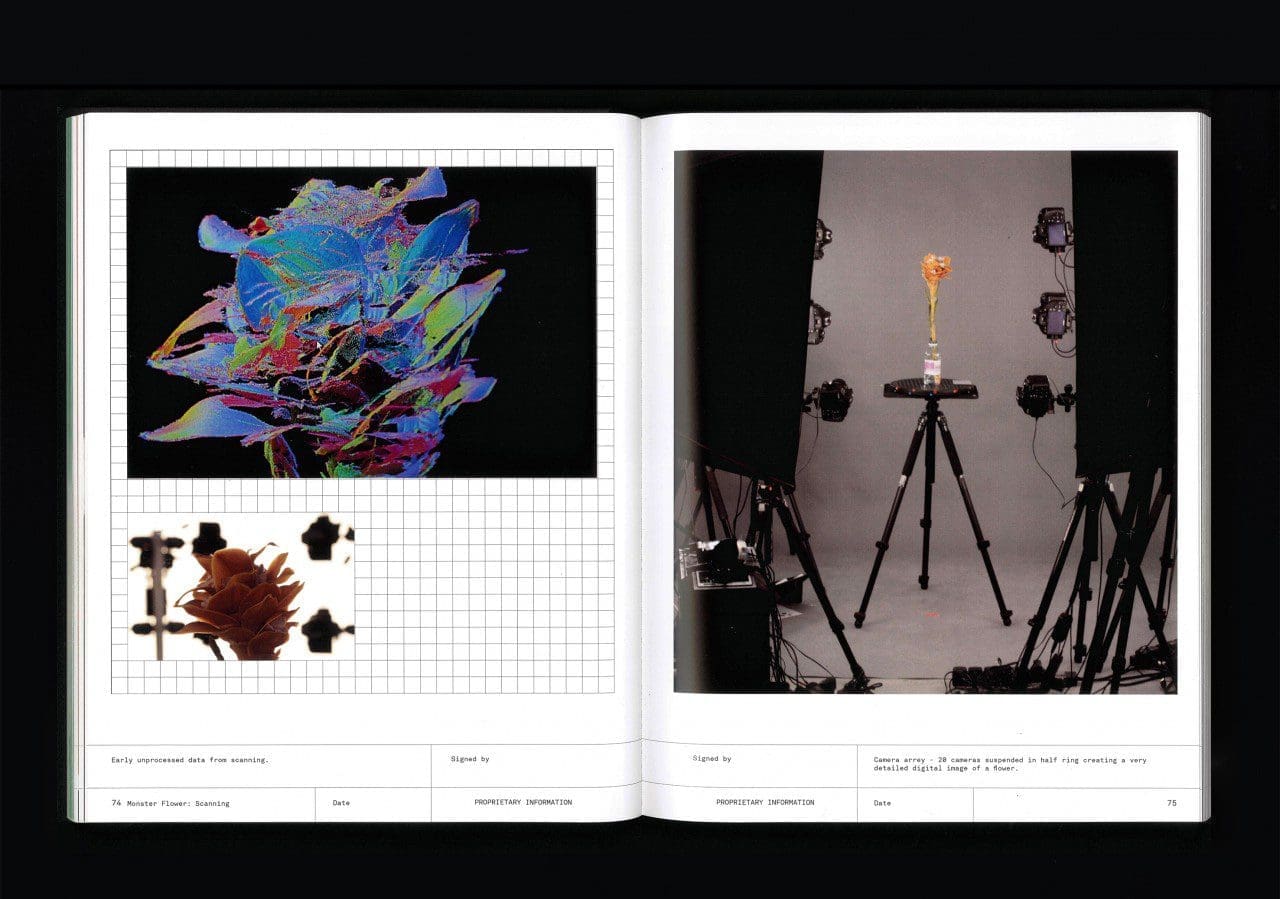

We created a number of hybrids. Each one came from a purpose. The way that they look is accidental. We were never thinking about them aesthetically. So when I came to the UK I had about a day to scan the first one. We used a camera array – 20 cameras standing in a circle. They shoot constantly while the object is spinning and they build up a 3 dimensional digital image. However, this digital file has no functionality. It can’t be printed. So I hired a 3D sculptor, Ignazio Genco, who then spent two weeks re-sculpting the digital files on a computer, so that they could be printed. The original one was made out of 22 separate 3D printed pieces, with a steel structure inside. It took 72 hours of straight printing.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

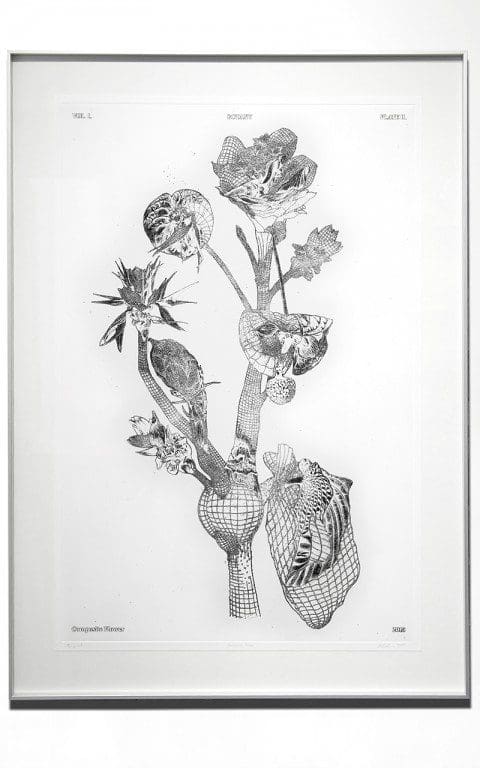

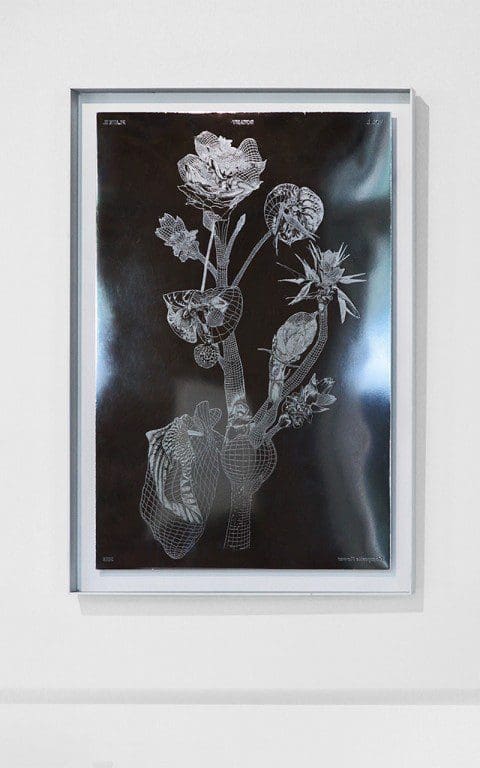

So that was the research, but I wanted to go further in telling the story. So I made these printing plates, like in the 16th century, when they discovered a new species of plant they would create a drawing of it and make multiple prints of it. So I started working with an illustrator, Clara Lacy, and we did it exactly as they would have done it, so we had the blow up details with information, we acid-etched it on copper, then we made the prints – monoprints in a run of about 15 – and then we chromed the plates to make them into permanent artefacts. I also produced a book of the whole process, as I wanted to extend the story as much as possible.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So that is how my practice works. Half of it is research, where I spend my time and money investigating what I’m really interested in, and then the other half is taking bits of it and translating it into ‘object’ work, which is where the recent resin work comes from. That all started with the research I was doing into aging materials. I was really interested in the ephemeral, the idea of value, the idea of things not being permanent.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Tell me how this vase encapsulates those ideas and values.

We have so many things around us that we don’t really necessarily want to keep – we are stuck with their materiality – like a mobile phone case for example, which is useless after two years, but you are still stuck with the object. So I started thinking of how to make objects that aren’t permanent.

So you have a vase like this, which is made with organic binders, tree resins, shellac, beeswax, cooking flour, and dried flowers. This one (Perishable Vase III) is made with shellac, which is a natural resin excreted by beetles. I mix it with flowers, which I collect and dry and process and organise in ‘libraries’. Then I make this material and then I form it in moulds to create the vases. Because it is made from organic and natural materials the idea is that, if you don’t take care of it – for example if you put it outside – within a month it would just disappear. So there is this contrast where you create something which visually you might appreciate, but you have this back thought that it will disintegrate if you don’t take care of it. So I wanted to get people to think about objects by making something that is not permanent.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III (detail).

Perishable Vase III (detail).

There’s also the idea that it is something you don’t have to have forever.

Yes. I wanted to make an inkjet printer with this technique – looking at the idea of planned obsolescence, where a printer is designed to print 5000 pages and then it breaks down and you have to buy a new one. So if you could use this material to make a printer body you could just dump it in your garden when it is finished with and it would rot. But this material is so far away technically from what you need from the body of a printer that I decided to create a more symbolic piece, which is a vase.

And then the investigation into nature is an extension of that, thinking of the process of aging, not necessarily actually disintegrating, because of course I do actually need to sell things, but I was really interested in creating a material that evolved, so that you don’t replace it, but you want to experience the change. In the way that brass or leather age and we appreciate it for what it is.

So I started working with this PhD research graduate from Kew, and we started injecting bacteria into flowers and casting them in resin. When resin cures it reaches very high temperatures, so the bacteria needed to be able to live without oxygen and at really high temperatures. So over time the bacteria destroy the flowers within the resin, but leave the form of the flower trapped in the resin. The idea was to create a material in which light would eventually replace the flowers within, like ghosts. I had this vision of this strong black resin and then light comes in and you only see the voids after the flowers have disappeared.

Then, instead of bacteria, I started using air, because air does a very similar thing. If you allow air into the resin then the flowers shrivel and die and gradually you see this halo of light around the structures. In the Flora Table you get this silvery effect. So the flowers don’t rot and go brown, they don’t disappear, they just start becoming silvery, with these voids of light around them. So a bit like a Flemish painting, but with the aging factor.

I was also interested in going back to this idea of natural decoration, how often we are inspired by nature to create decoration, but how rarely we use nature itself to create decoration.

I started casting the flowers in big blocks of resin and slicing them up and opening them almost like a cheese, and then misplacing the slices. Each of the slices in this screen comes from four different resin blocks of flowers. Sometimes I keep track of how I cut them when I reassemble them, other times they are arranged completely randomly.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Do you fabricate all of these pieces yourself ?

I did! It was really hard work. I made these pieces for an exhibition last September, and I was late with everything. When you are coming up with a new material there is so much to learn through the process. You think you know and you keep learning. I am still learning so much from this material. I didn’t know so much about resin at the beginning, so I made these moulds and added too much catalyst, and the resin started bowing because it was shrinking too much, it was curing too quickly. So I had to do a good few runs of resin casting to get the result I wanted. Then there was so much work with cutting them and sanding and so on.

Now the process is much better. I have specialists that I go to with certain things, but I still do all the flower collection. Until recently I was also doing all the casts on my own, but because each object becomes bigger and bigger – right now I am working on a commission for a 2 metre long table – so the scale of the project requires other people, more pairs of hands. So I work with resin specialists, metal specialists. I am still very engaged with the work. With the resin casting I do all of the arrangement of the flowers. I do a few arrangements at the same time and then choose the one that I like the best. It’s a bit like painting. You choose them for their structure, but also for their colours, volumes, and then make these compositions. Once I am happy with a composition it goes in to be cast. Still during the casting there are so many things that can go differently.

I use a mix of both dried and fresh flowers. I have the size of the mould, so I know what my ‘canvas’ is, and I have all my plant libraries, which I take with me. I have times of the year when I collect a lot, and dry them and then have to keep them dry. When I need fresh flowers I get them when I need them. And then I arrange them and then there is the casting procedure.

It took me a year to get to the point where the flowers weren’t burnt or shrunk by the resin, nor for the flowers to affect the resin curing, because if you put moisture into the resin it prevents it from curing properly. It’s a very slow process and took a lot of development to get there, but I’m not going to give away my recipes!

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

What is intriguing about your work is that it is clearly very complicated to produce and yet the pieces are very simple.

There is so much technicality that goes into it, and it requires a lot of specialists. It has also been a problem with my work that producing it was really expensive at the beginning when I was producing in a self-initiated way, rather than with commission-based work. And when you are a recent graduate you find it really hard to do, which is one of the reasons, to start with, I did everything myself.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table (detail).

Flora Table (detail).

Are you primarily being commissioned to produce the furniture items at the moment ?

Yes. Actually creating the furniture work – the easiest to understand for people – has helped with the appreciation of my other work. People started getting the idea of the decaying vases much better and so I started getting commissions for these too, and now I am doing these resin pieces made in the same way as the screen, that are more like paintings. They will be framed and can also be used as wall panels. So half my work is commissioned work, and the other half is just me putting time and effort into investigating new things.

What are you working on right now ?

Right now I am working on a flower incubator. It comprises this desktop ‘machinery’ – all of the parts form a complicated system of water exchange, temperature control, hydroponic nutrition – designed to prolong the life of a cut flower to see how much longer we can possibly extend its life. So this is the opposite of the idea of constant disposable consumption. It is taking something that is already starting to decay and attempting to give it longevity.

The incubator is technically a very challenging project, and so I am having a lot of help with different specialists, so it is taking much longer than previous projects. Generally I have realised that I must take as much time as I need to develop what I want to do, rather than pushing things too quickly. It’s quite easy in this world to get trapped into working with other people’s deadlines, especially interior designers, as aesthetically the resin pieces are being seen as statement pieces for interiors. So currently I have quite a lot of enquiries from interior designers wanting to use these furniture pieces in their work.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

How do you manage that in terms of how people perceive your work ?

I am only just starting to realise that there are these differences between, say, the interiors world and the art world. When I started, for me it was all the same, I didn’t really know. Because I’m so interested in the idea and what these pieces are conceptually the selling outcome was something far from my mind. Now I am starting to distinguish how much work and commitment actually goes into creating a working piece of furniture. The resin material gives them an added value, but what I am most interested in is creating the value in the material itself – by the fact that it ages, or is not permanent.

So I am trying to shift my practice right now into this world where the pieces are appreciated for the conceptual idea. I spend quite a lot of time going out and talking to people, giving talks, to explain the work, because if you put a vase like this on a plinth and you just leave it as it is without a label people just say, ‘Yeah, it’s a vase.’, but if you give the story of why it was made and what it’s going to do in a couple of years they really perceive it differently. So the longer I am working the easier it is to make the work because people already understand it. At the beginning it was really hard to come up with the idea and have people understand it. The furniture pieces give people an easier point of entry, as people like them first for their visual aesthetics, and then when they get deeper they realise that there is this whole body of work. Of course, aesthetics are a very important part of my work. Not as the ultimate outcome, but more as the result of an investigation into aesthetics, either through making natural decoration or the aesthetics of things that decay and don’t last. I think aesthetics are incredibly important and we should never forget about them, but they are never the primary goal in my work.

So where do you see your work going ?

There are still two paths currently. One where it is more applied fine arts, and the other is me investigating this idea of impermanent things. I’m in a group show in September. I’m doing more of the vases for the show. And I’m thinking of making a decaying glasshouse where the front of it is so fine that it just disappears. That’s something that really stimulates me and gives me energy to work.

It’s also a lot about grabbing from the pool of inspiration from the past and mixing it with everything I am doing right now, like the story of flowers and the consumption aspect. One feeds the other, and then they start to feed themselves. So I guess I’ll see where that goes, but I’m really about thinking through making, so I have to be making to come up with things. It’s never just me thinking about making something and then doing it, they are all an outcome out of the past research, my palette of tools and materials, and you go with all of them until something starts getting somewhere and then you pick the ones that go somewhere and start working on developing them further. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go. I’m working on having a different creative head space where it’s all about making, so just letting myself make mistakes and experimenting.

Nowadays we are so keen to have ‘new, new, more, more’ all the time, I am trying not to get trapped in this way of thinking and take time to actually develop these approaches I have started as far as possible. My practice is also a lot about people being able to come and see the pieces, so I am really happy to now have a space where I can meet people and show them the work and explain the ideas. For it is one thing to see an image on the internet, but quite another to come and talk to me about where it’s coming from, and also the possibilities of what I can make for them.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology (detail).

Flower Entomology (detail).

Can you tell me about your relationship to nature, gardens and flowers ?

I would say that it keeps coming more and more. I started off as a blank page where I was interested in other things, but the more I work with these objects the more I appreciate nature. I have started thinking about flowers very differently. I don’t have this need to have them around me so much, as I look at them as a kind of material, and I see so much waste that it terrifies me to even think about going to buy more of them, and I don’t have a place where I can grow them as I live in central London.

Strangely plants have become a lot more intriguing to me, also because of my investigations and my talks with plant geneticists, but on just a very personal basis they have become much more, I would say, friends, where they are just this amazing source of nature you can hold in your hand. My room-mate shares the same idea and we now have more plants in our flat than I think we do cups ! It makes home so much more relaxing, especially in London.

And if you think that my past was in this 2 acre central Warsaw garden – because not only did we have the glasshouses, we also had a very particular garden, because my grandfather grew not only flowers, but all the garden plants as well. Then I lived first in the Netherlands, a small city with not all that much nature around, and now I am in London, and I am missing it a lot, which is why I have this desire to go and be in nature every now and then.

My sister and I have also just started a business together around flowers, doing artistic flower installations in Warsaw, because first of all it’s something that she is really into – it is in her DNA, she was never trained – but she just makes these amazing compositions and arrangements, and there is a big niche there for that there, as all the florists are doing the same kind of thing. No one is really thinking of flowers in terms of them being local or seasonal, or in working on the composition almost as a sculpture or painting. We’re using the same name as my grandma used to call her flower shops, which is MÁK, which means poppy seed in Polish. We only started about 4 months ago and so I am travelling to Warsaw a lot more at the moment, because we are doing this together, as she’s very young, she’s 25, so I am trying to support her, but she is the main engine and inspiration, she does all of the compositions herself. And she dries flowers for me too. She uses lots of flowers in her installations and everything that comes back to her is being dried and re-used in my work.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

What would your grandfather think ?

I’m really curious. He was a very complicated man with a very complicated way of connecting with his family so I didn’t really know him that well, but I think he would be secretly really intrigued and interested. I sometimes wonder what it would be like if I could go home and talk to him about these things and get his knowledge. My sister is always seeking knowledge about plants and my mum tries to give us as much of her knowledge as she can, but I think my grandfather would be an amazing source. Lately I have been digging through all the family archives and going through everything, because I have been trying to find a book of his – you know when you are a grower and you discover and record things for yourself ? – so I’m trying to find these transcriptions of what he was doing.

We had four or five really big glasshouses, and it was funny as it was in central Warsaw and he sold it to a development company, who took down the glasshouses, but they promised to keep the garden, because that was his condition. But they tricked him and they took it all down and built these big buildings and only kept a tiny bit of the garden. It was really sad, but we managed to rescue all these massive trees, and they were transported to my parents house on these huge trucks. They had to wait to build the house until the trees had been planted first.

Your work straddles worlds of art, craft and design. How do you classify it ?

With the craft, I think I was kind of put there more than it was a conscious decision on my part. But it’s so close to everything. It’s hard to even name it for myself. Like, when people ask me, “So, what do you do?” I seriously have problems answering this question. And it’s not because I’m trying to be so ‘artist’ about it. It’s just, how do you explain that it could be objects that don’t last, or it could be research in the Netherlands, or it could be investigating an actual decoration and making these resin pieces, or it could be ephemeral textiles ?

It is hard these days to say what it is. I don’t feel the need, or able, to classify it. It is what it is. It is other people who need it to be classified. That is fine with people who are open, and who are prepared to listen to me explain the ideas behind it, but closed people find it harder to grasp the idea of buying something that is ephemeral. It’s hard for some people to see value in something unless everyone else does. Some people at the design fairs have said that my work shouldn’t be categorised as design, but really that is just a tag for it. How people see it is how they see it.

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

Previous

Previous

Next

Next