Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

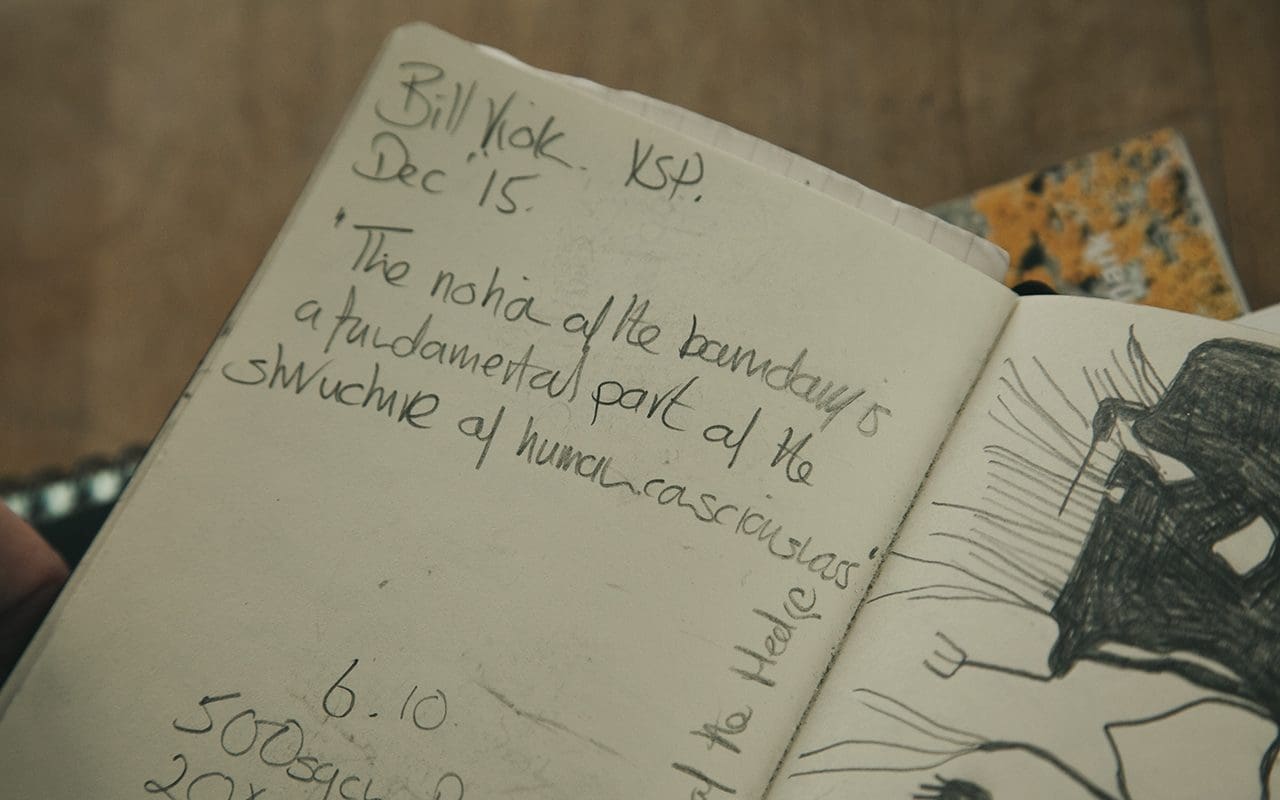

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

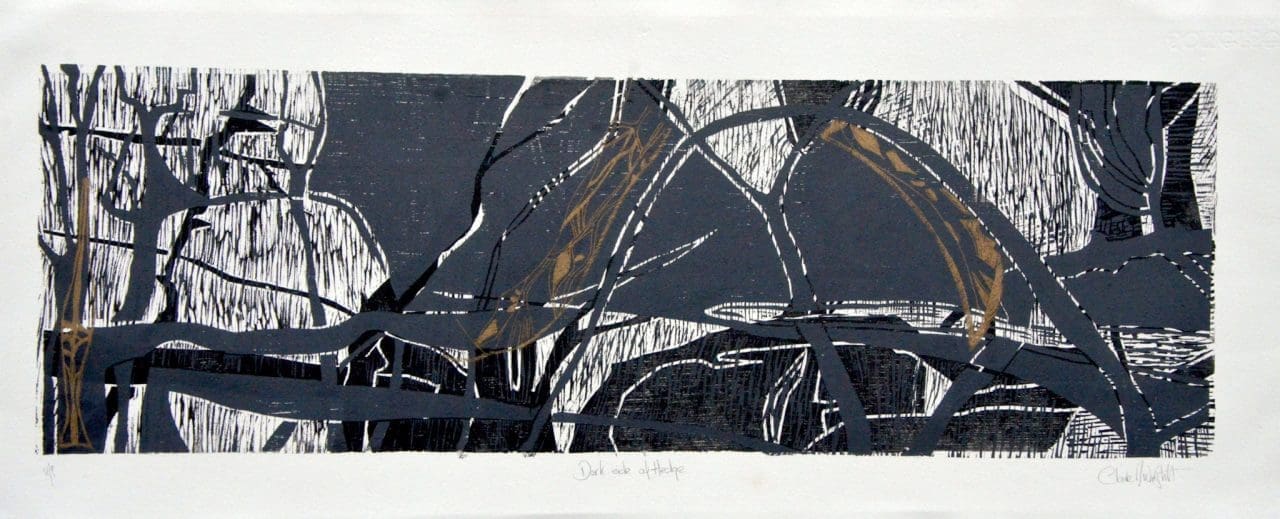

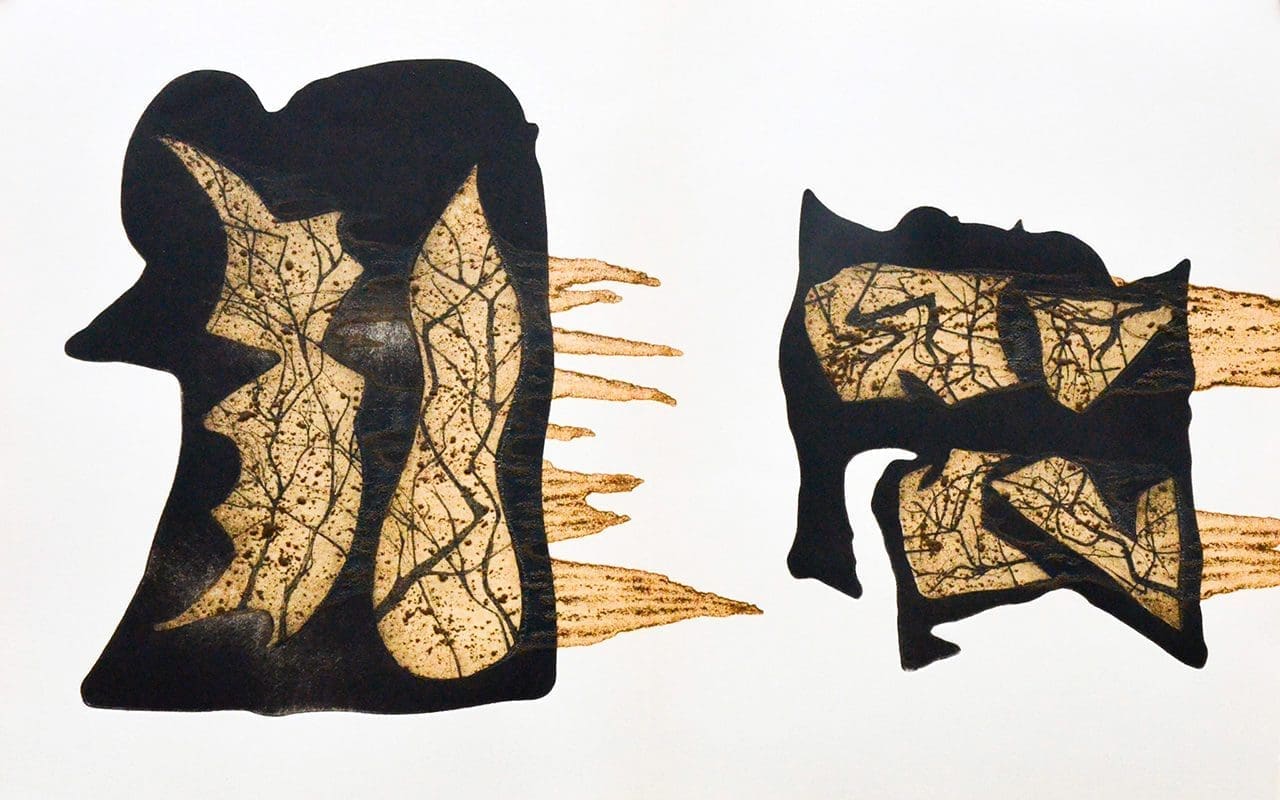

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

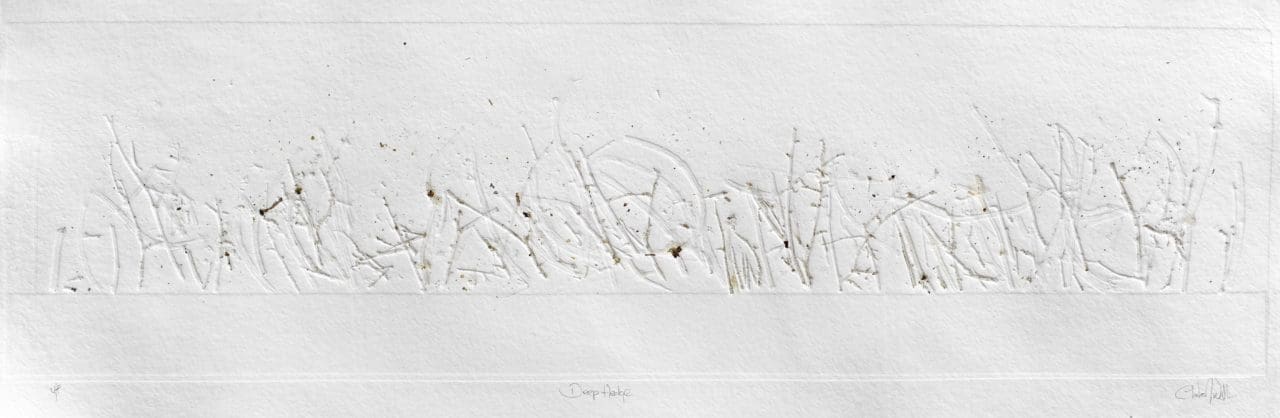

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

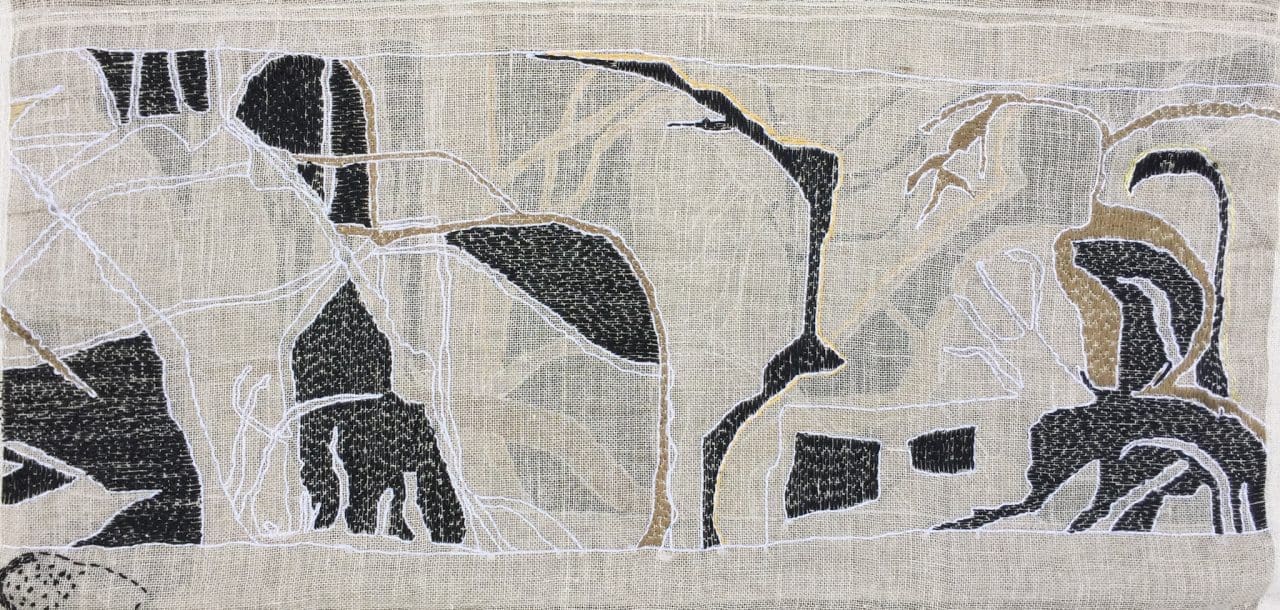

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

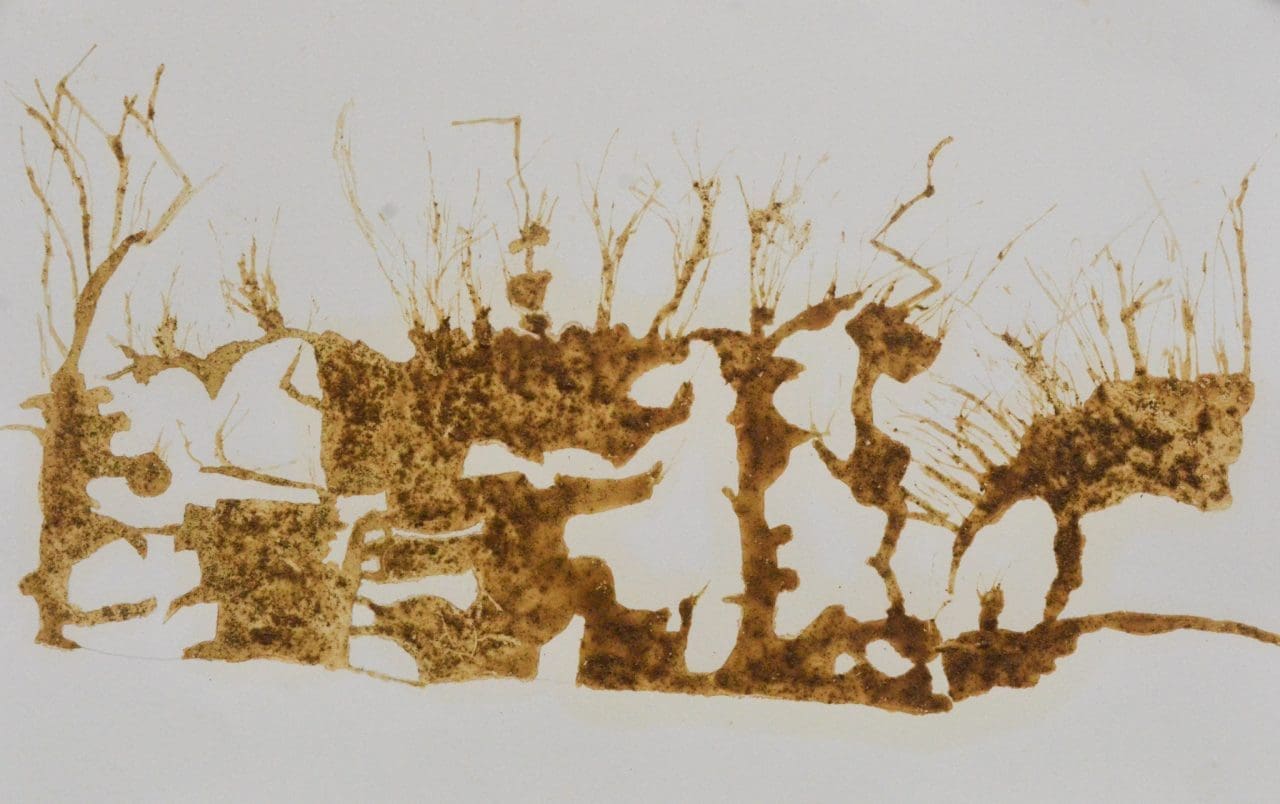

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

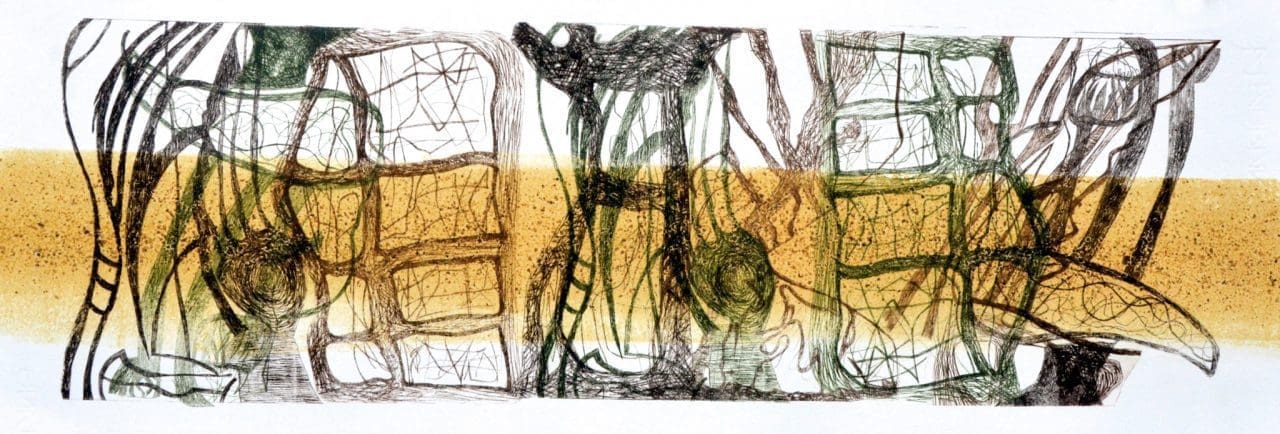

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

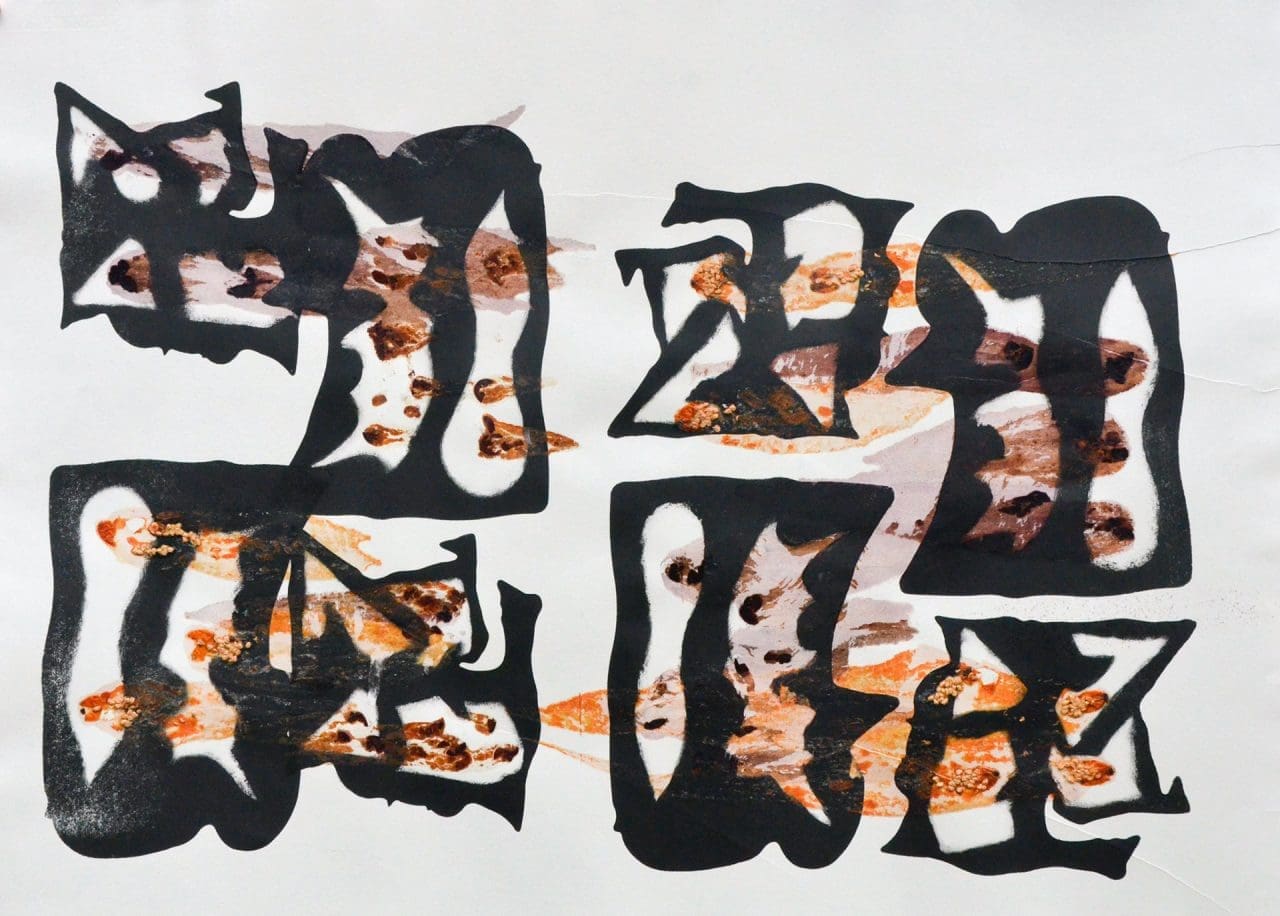

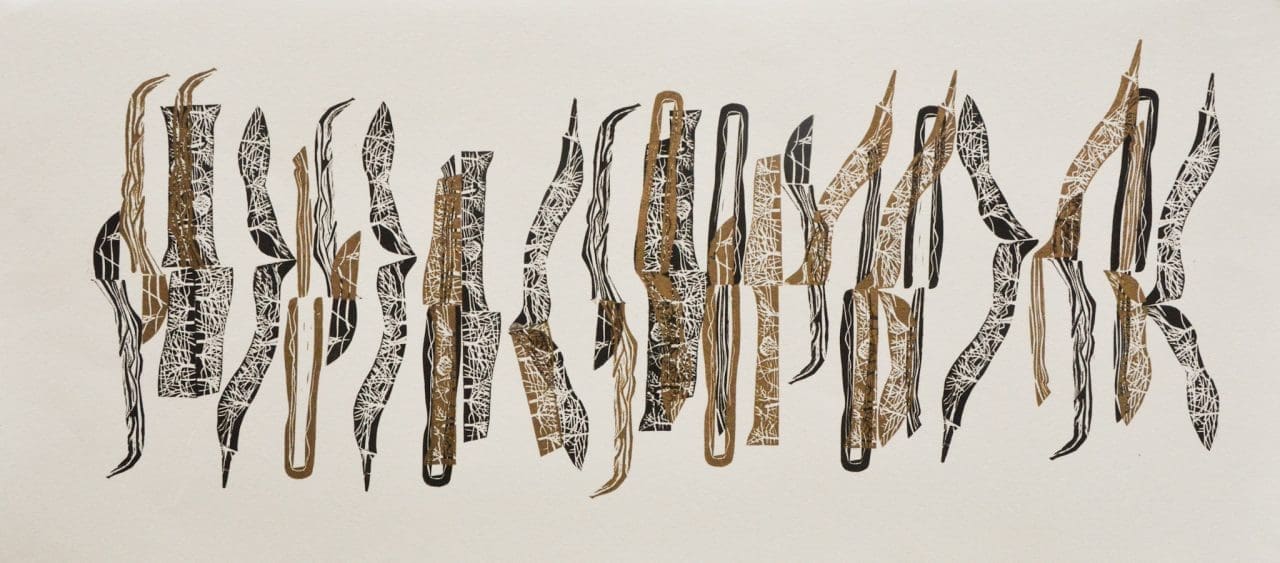

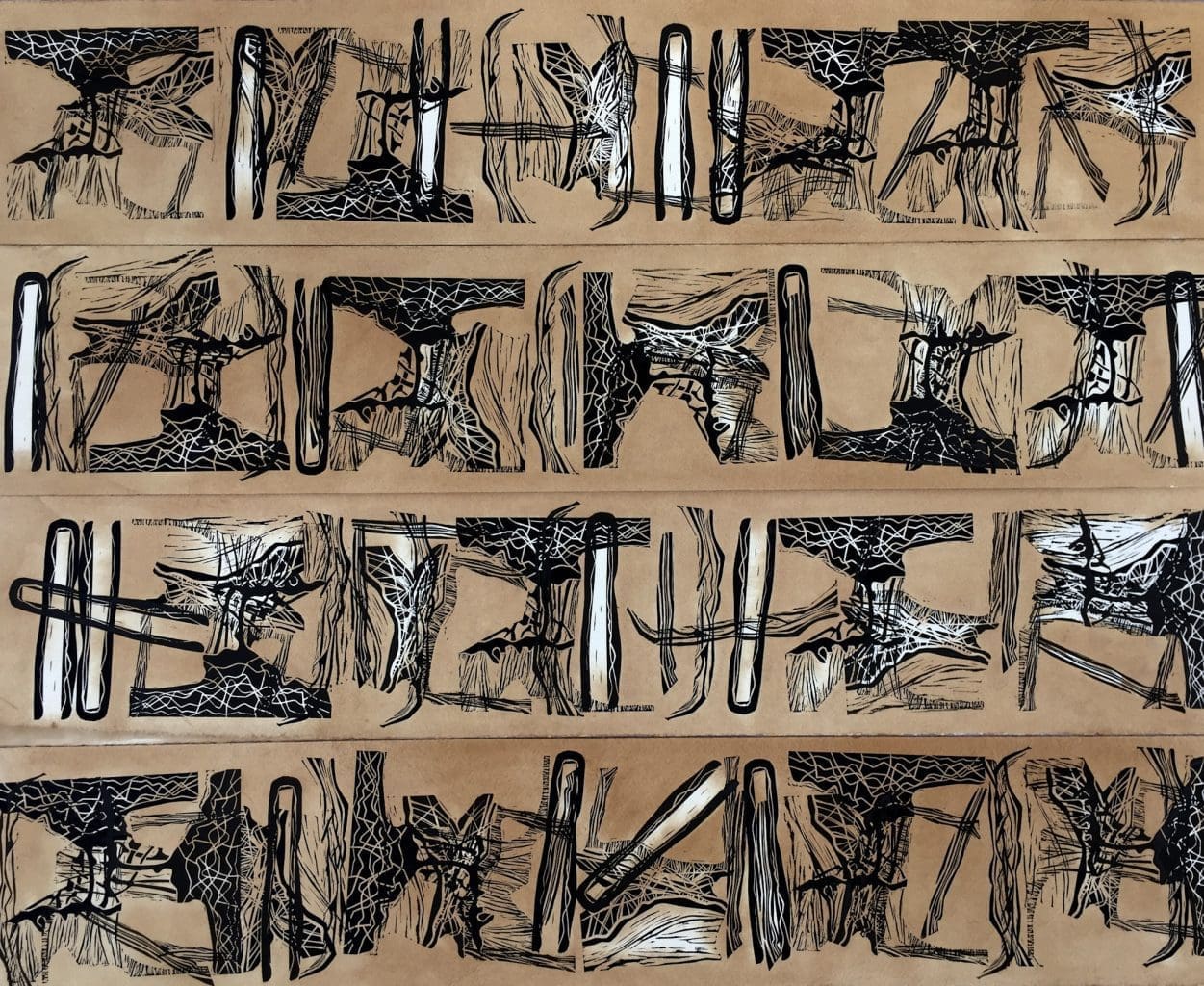

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

Previous

Previous

Next

Next