This time last week we were still reeling from the excitement and stimulation of the first Beth Chatto Symposium. Originally intended to celebrate Beth’s 95th birthday this year, following her death in May the event became both a memorial to her and a celebration of her influence on a generation of gardeners, designers and nurseries, both here and overseas.

The symposium was the idea of Amy Sanderson, a Canadian gardener and florist who has spent some time working at the Beth Chatto Gardens in recent years, and was organised by Amy, Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg. When the symposium was announced early this year they anticipated in the region of 150 attendees, and so were thrilled when over 500 people from 26 countries bought tickets. Åsa told me that they could have sold many more.

The theme of the symposium was Ecological Planting in the 21st Century, and the line-up of international speakers included gardeners, garden designers, academics, nursery-people and growers, all with their own take on the subject, although a number of key themes became apparent over the two days. The talks were recorded and will be posted on the symposium website as soon as they have been edited.

In the main image above are, from left to right, James Hitchmough, Dave Ward, Taylor Johnston, Olivier Filippi, Marina Christopher, Peter Janke, Dan Pearson, Midori Shintani, Keith Wiley, Andi Pettis, Peter Korn, Åsa Gregers-Warg, Cassian Schmidt and Amy Sanderson.

James Hitchmough

James Hitchmough

Opening and closing the symposium were presentations by James Hitchmough, Professor of Horticultural Ecology in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Sheffield. James has done a huge amount of research into seeded naturalistic plantings over the past 30 years and, as an academic and researcher, was generous and instructive in the information he shared. He was very clear in communicating the ecological value and function of designed landscapes, but explained that the highest value and most stable functioning of a planting is achieved through its ability to persist – its longevity. This is directly linked to biomass, since the denser a planting is both above and below ground, the less unwelcome weed species are able to invade it. The layering of foliage above ground, from groundcovers through to tall emergents, also shades out weed species, creating a more stable planting. He advised that the biggest challenge in dynamic naturalistic plantings is identifying what they are to become and how to manage them with this guiding vision in mind. All of these observations rang true.

Keith Wiley

Keith Wiley

All of the speakers spoke about the inspiration they have taken from observing native plants in the wild, and both Keith Wiley and Peter Korn spoke passionately about their travels to Crete and South Africa, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and North America, respectively as being hugely influential on the ambitious private gardens they have both created in Devon and Sweden. Keith was, for 25 years, the gardener at The Garden House at Buckland Monachorum, one of the most influential gardens of the 1990’s in bringing naturalistic planting to the attention of a wider audience. His talk focussed on the aesthetic possibilities of combining plants as they appear in nature, and he illustrated it with lush images of highly colourful, exuberant plantings.

Peter Korn

Peter Korn

Peter explained the challenges he had set himself by wanting to grow as wide a range of dry-climate plants as possible from all over the world, in an inhospitable climate and with the added difficulty of high rainfall and sub-zero winter temperatures. Both explained in detail the lengths they had gone to in order to create specific microclimates and soil conditions to allow them to grow some of their favourite species. Of great interest was Peter’s method of growing plants in deep sand, which both encourages the formation of stronger mychorrhizal communities and presents a hostile environment for self-seeding weeds.

Cassian Schmidt

Cassian Schmidt

Similarly, Professor Cassian Schmidt, Director of Hermannshof Garden described the creation of a large number of habitat types to showcase a wide range of plants in this public garden located in Weinheim, near Heidelberg. Originally based on the ecological principles of Professor Richard Hansen, Hermannshof now has in excess of 18 habitat areas from North American Prairie to East Asian Woodland Margin and European Dry Steppe. In tune with James Hitchmough, Cassian also described the importance of plant ‘sociability’ when planning plantings, choosing plants with compatible growth habits and cultural requirements to build persistent, self-regulating communities. His experiments with dense plant layering, and the use of primroses as an early-season, weed-supressing groundcover encouraged us in our own thoughts about these as a means of closing the ecological gap in our own plantings.

Peter Janke

Peter Janke

Fellow German, nurseryman and garden designer, Peter Janke, worked at the Beth Chatto Gardens as a young man in his 20’s, and was hugely inspired by Beth’s experiments and success in the Gravel Garden. After returning home he introduced her teaching of using plants best suited to the habitat conditions in one’s garden to an audience of German gardeners. Peter spoke about the challenges posed by the recent high summer temperatures, which have been especially extreme where he lives in central Germany, and described how he created his own garden, based on many of Beth’s planting principles, in particular a gravel garden of his own, which has performed remarkably well this year.

Olivier Filippi

Olivier Filippi

French nurseryman, Olivier Filippi, spoke passionately about planting palettes for Mediterranean and dry landscape plantings, the development of which he is at the forefront of, supplying projects all over the mediterranean. Although many of the speakers talked of striking a balance between aesthetics and function, Olivier was very clear that, in a dry climate, a functional landscape is, by necessity, a beautiful one. He described the use of cushion-forming, evergreen sub-shrubs as key in his work, and flower as the least important aspect in making plant choices, leading to an appreciation of the ‘black and white garden’ where rhythm, form, texture and contrast are the primary considerations. He also spoke vigorously about the need for water conservation and encouraged the audience to regard maintenance as one of the most enjoyable parts of gardening. He was also dismissive of current trends for using only native species in plantings, arguing that, in relation to the scales of planetary time and geographical change, such a stance was limiting and myopic.

Andi Pettis

Andi Pettis

As a complete contrast Andi Pettis, Director of Horticulture at The High Line, spoke of the very particular challenges of gardening in an extreme urban environment. As well as the technical and organisational difficulties of maintaining a podium garden high above the ground. She also focussed on the relationship between the public and plants, and the fact that people are also a part of landscapes and their associated ecosystems, whether natural or designed. Like Cassian Schmidt she also spoke passionately about the educational benefit of a public park where horticulture is paramount, and how, even in the centre of one of the busiest cities in the world, it is possible to get people to engage with and appreciate natural cycles and rhythms and ecology.

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan with Midori Shintani

Dan had also been invited to speak, and he did so primarily about his work at the Tokachi Millennium Forest, although he too illustrated the fundamental impact that Beth Chatto had had on his early understanding of plant habitat requirements, and the importance of creating planting schemes that are culturally balanced and in context with their surroundings.

His talk was followed by one given by the Head Gardener at the Millennium Forest, Midori Shintani, and her first public presentation in English. Midori talked of the ancient Japanese belief in animism, the power of all natural things, of the landscape, and of nature worship. She also explained the importance of satoyama, the term used to describe the territory formed by the intimate relationship between man and the productive agricultural landscape at the boundary of the wild. These ideas were then developed as she explained how she and her team of gardeners approach the work of maintaining, not just the designed landscapes at this public park in Hokkaido, but the very forest itself. She spoke beautifully and with great tenderness about the fact that everything is connected, and the importance of taking great care and making close observation of natural processes. She expressed the deep interconnections between people, landscapes, natural habitats, plants and fauna with immense simplicity and lightly worn wisdom. It was no surprise to find that, as she delivered her final words and the hall filled with applause, many in the audience were crying.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 September 2018

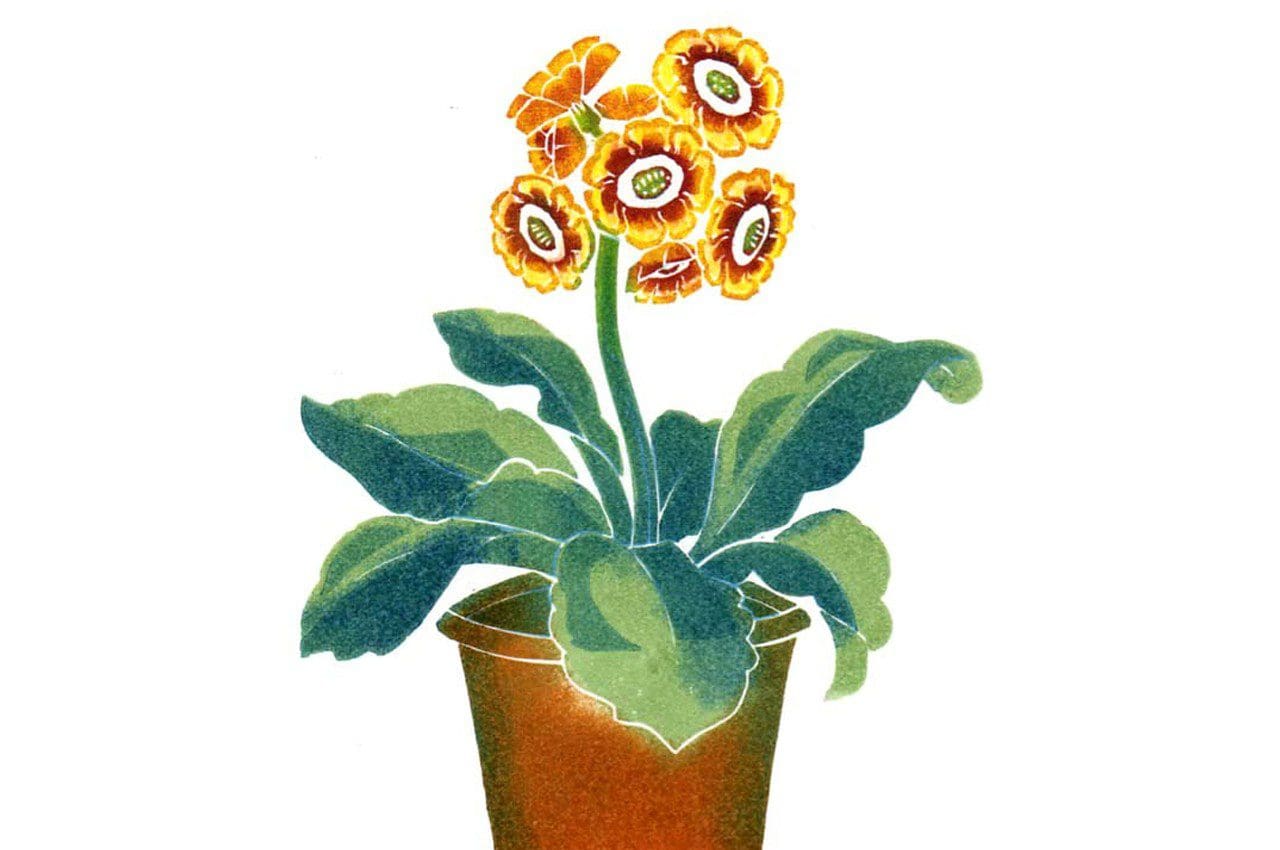

Lucy Augé is a Bath-based artist who has an passionate interest in the variety of flower and plant forms which she paints with Japanese inks on a wide range of specialist and vintage papers. Her intention is to capture the ephemeral and fleeting moment. We met last year and, after introducing her to the Garden Museum, she showed some of her new tree shadow paintings there earlier this summer. Since June, Lucy has been coming to the garden at Hillside to capture a range of the plants here on paper.

How did you come to be an artist ?

I always wanted to be an artist, even from being a child. For my tenth birthday I didn’t want a party, but wanted to go to Tate Modern, as it had just opened. I think my mum thought, ‘Oh God. Choose another career path !’. I had always been creative at school, I was never really academic, so I got funnelled down a channel into being ‘artistic’. That then followed me through to college, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist, so I did graphics, and thought I’d go into magazine design, as I had a passion for French Vogue at the time as it was so well art directed.

Then I had a really bad brain injury from a fall, and that left me very, very ill, at home. I couldn’t go back to university. I couldn’t do much, as I was having four seizures a day, and thought, ‘OK, life’s over’, but then I started gardening with my father, and that’s where I started noticing – I was going at such a slow pace, because I was so ill, I’d have to be carried down to the garden – and I started noticing things more, because I didn’t have any distractions. I didn’t have a phone for two years. Not that I was cutting myself off, I just didn’t need it. So I just started looking at nature all the time, and then I just started painting it. Repetitively. Or I was watching gardening programmes on repeat, because I wanted to know more, all the time. So, that’s where, through the illness, I got the passion for gardening and my painting.

When I finally went back to university I just felt it was very redundant for me. I went back to the graphics course as I was already a year in and because I don’t really like to give up, but I knew the tutors didn’t really like my work. They were looking for a very graphic, computer-generated style of work, and I then generally only worked in felt tip, keeping it hand drawn, but still trying to fit in with the current look that was around at the time.

So what happened after university ?

I got picked up for projects while still at university and, when I graduated, I did packaging design and worked with Hallmark, but I quickly knew I wasn’t an illustrator, as I can’t draw just anything and my passion lay with nature and studying that, rather than drawing a family of badgers eating cake. No joke, that was an actual commission.

The 500 Flowers exhibition came about after a month I spent in LA in 2015, where I had a meeting with the art director at Apple of the time, who had offered to mentor me. He set up a meeting with a carpet designer who I was supposed to do collaboration with. However, when he met me he told me that I wouldn’t be an artist unless I married someone rich, and that he would only work with me if I got someone to buy one of his rugs.

I was enraged by this and thought I was tired of waiting for someone else to launch my career for me. So I came home determined to make an impression alone, booked a rental gallery space in Bath and put on my first show on my own. The idea originally was to paint a thousand flowers, but that was near impossible in the time frame I had set myself. My brother calculated I would have to complete one every ten minutes ! So I painted five hundred, with the aim of painting every species that I came into contact with.

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

You produced all of that work and organised the exhibition yourself. What was that experience like ?

Well, I had five hundred A4, individually painted ink drawings, which I had completed in three months, and that both evolved my style and I became very confident at drawing. I also priced them at £40 each, which I think some people thought was madness, but at the same time nobody knows you, you have no reputation, and so £40 can seem like a lot for someone, but it was great because it made it affordable so that people would buy maybe nine or twelve at a time. An interior designer, Susie Atkinson, bought sixty. And so it got my name out there, because I was affordable.

The exhibition took place in Bath and I made sure I had beautiful letter-pressed invites. I invited everyone I’d ever met, contacts I’d made on Instagram or through business or who had shown an interest in my work. I invited people who I really admired for their work, which is why you and Dan got an invite. I just wanted to show people that this is what I do, this is my passion and if I fall flat on my face and no one comes and nothing sells, at least I would have known that I’d given it 100%. And then I’d have gone and got another job !

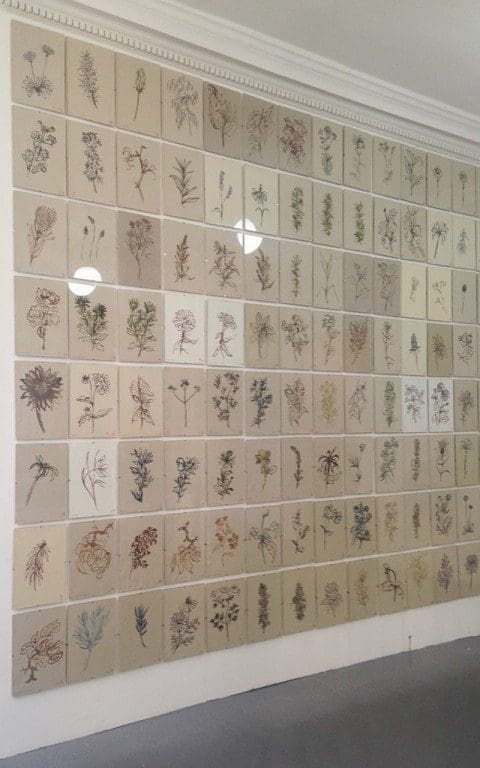

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

But it worked out in my favour. I had a queue out the door on the first night. I sold over eighty in the first couple of days. Then House & Garden emailed me to ask if they could have nine for their show, which the editor ended up buying. The assistant editor then bought another nine, and she put them up on her Instagram and I ended up selling out in five months. That then led to shows in Japan, San Francisco and elsewhere. It confirmed to me that, yes, you are on the right path, you’re doing the right thing, and the proceeds of that first exhibition went towards buying my studio. Before then I was working in a barn with no windows, no natural light, no loo, and so that exhibition was my make or break. Otherwise you can be creating, and calling yourself an artist and saying ‘This is what I do for a living.’ and yet you’ve never really put yourself out there, and so I thought, ‘baptism of fire’.

Then I started getting commissions from people to go and draw on their land, their flowers, which was really great. The best of those was for Gleneagles, which was the highlight of my career. I was flown up to Scotland, where I’d never been, and stayed at the Gleneagles, which was an amazing experience, and I went round the estate and drew all of the plants that were there at that time, and they are now hanging in the American Bar. And it was just so nice to know that people understood what you do.

Were you starting to charge a bit more for them now ?

Yes, I did raise my prices. Although I didn’t charge a lot because I wanted people to have the chance to invest in my work. I come from…my father grew up with no money, but he was always passionate about art, and just wanted someone from his background to be able to go, ‘I’m going to invest in something. Something beautiful.’ So that they can own real artwork. And I think that is a real gift to be able to do that. Especially as I had five hundred ! And the consequence now is that they have travelled all over the world. I love that there are some in Singapore, and some in Brazil and I don’t think I would have got that kind of international reach if I had not priced them so competitively. Of course, now my prices have gone up and I don’t need to produce as many. My last catalogue only had twelve paintings in.

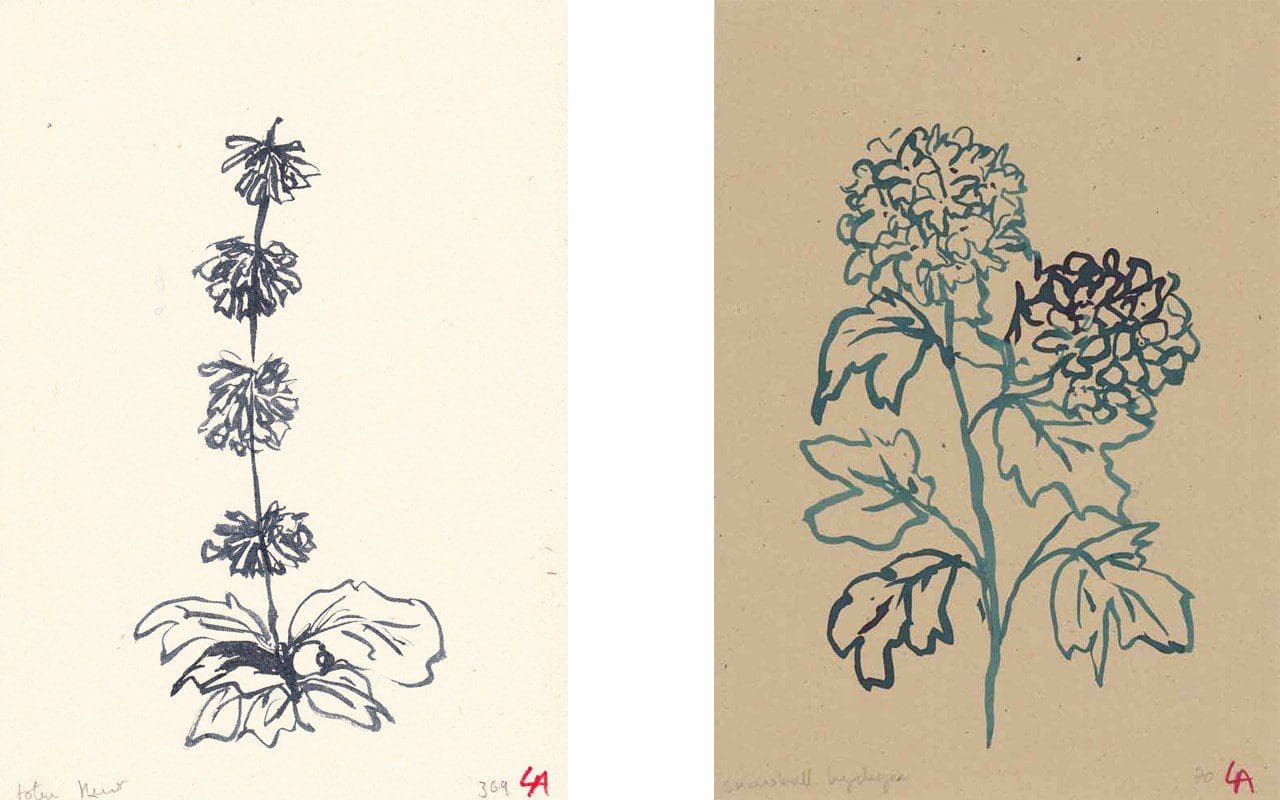

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

What was the medium you used for the 500 Flowers paintings ?

Ink. On antique paper.

I’ve seen some of your work which is very highly coloured and looks like it is done in felt tip ?

Yes, that’s right. That’s when I was still trying to be an illustrator. With those I was trying to fit in with the norm, so everything was very highly coloured for editorial. I would say that that was the only time I have ever tried to fit in. It worked for the clients to a point, but I kept being told, ‘Your work looks too much like you. There’s something to it, but it’s not commercial enough.’. So I gave it a year, doing that kind of work and I just grew out of it very quickly, because it wasn’t me.

There appears to be a strong Japanese influence in your work.

I love Japanese and Chinese art. I’ve always loved Japanese and Asian culture, so it’s always been in the background. Anything from there I could get my hands on I wanted to have a look at it, absorb it. Then I saw a show of Chinese paintings at the V & A, where I learnt that they were painting with natural pigments, so with copper and iron and earth and plants, and it just made this wonderful colour palette. So I found some Japanese inks that have that same antique colour palette, and it just felt much more me. It’s hard to put my finger on it, but it just started to fit better with the kind of images I wanted to make. And with the paper. I had never wanted to work on white. I had this antique paper, which had been in my godmother’s attic, which had the same feeling as the old Chinese papers I had seen, because they are made entirely from natural elements. So my choices were about aspiring to that antique colour palette. The other thing that struck me about that exhibition was that the artist was always invisible. The painting was never about the artist, it was about nature, landscape, weather, the seasons. It was about the everyday. And I thought, ‘Yes. Art can be like this.’ Because as I was growing up when everything was about high concept or shock, shock, shock or politics. The stranger the better. How far can you push it? And looking back at older art – one of my favourite artists is Monet – was deeply unfashionable and seen as suspect. But I love how he could just paint waterlilies and the resulting painting becomes this charged, emotional landscape.

Is that one of the reasons that you didn’t feel you could really be an artist ?

Yes, completely, and it’s one of the reasons I considered commercial art to begin with. Also I was never really encouraged at school, bar one teacher, to pursue my art. You were told that you needed to fit in. And I think as an artist you do need some kind of validation that what you are doing has value and that this is what you are supposed to be doing. And I never really got that until I put myself out there and had people say, ‘We want what you make.’ Because otherwise you can be drawing for just you – and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that – but you do have to decide that you are going to be an artist, and I made that decision after the success of that first exhibition.

I could have gone in one of two directions. I could have just put my flowers on anything and gone down the commercial route, or choose to refine the work and make it more considered. I have had a few commercial collaborations, but I have been very choosy about who I have agreed to work with or who I have approached. And I then reined it in and have now moved my work away from it, as people lost the meaning behind what I was trying to do. So they just wanted a picture of a lily as their daughter was called Lily, which is fine, but it missed the ethos of the work.

Which is ?

Seasonal observation through nature and plants. Forgotten moments. The immediacy of right now. I always found it interesting that the first pictures to sell out always are the ones of weeds. Those are the ones that people really want. I think because, as soon as you paint them, and strip everything away, you can see the beauty in them, and the fact that they are so mundane, but the painting elevates them. Honours them.

Do you know that there are 56 seasons in Japanese culture that relate to the flowering times of 56 different plants ?

No, I didn’t. How fascinating. I can so relate to that. I get quite anxious at the possibility of missing things. You know, like cow parsley. I’ll have a great idea, and then two weeks later I’ll have the time to get onto it, and all the cow parsley is gone ! So now I prep my paper in advance and cut it to the size that I want so that, when that moment presents itself, I can just say, ‘Here I come !’. That’s why when I came to your garden I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s definitely going to be, sorry to say for you, a much longer process than I had envisaged, as I now would really like to be there in different seasons.

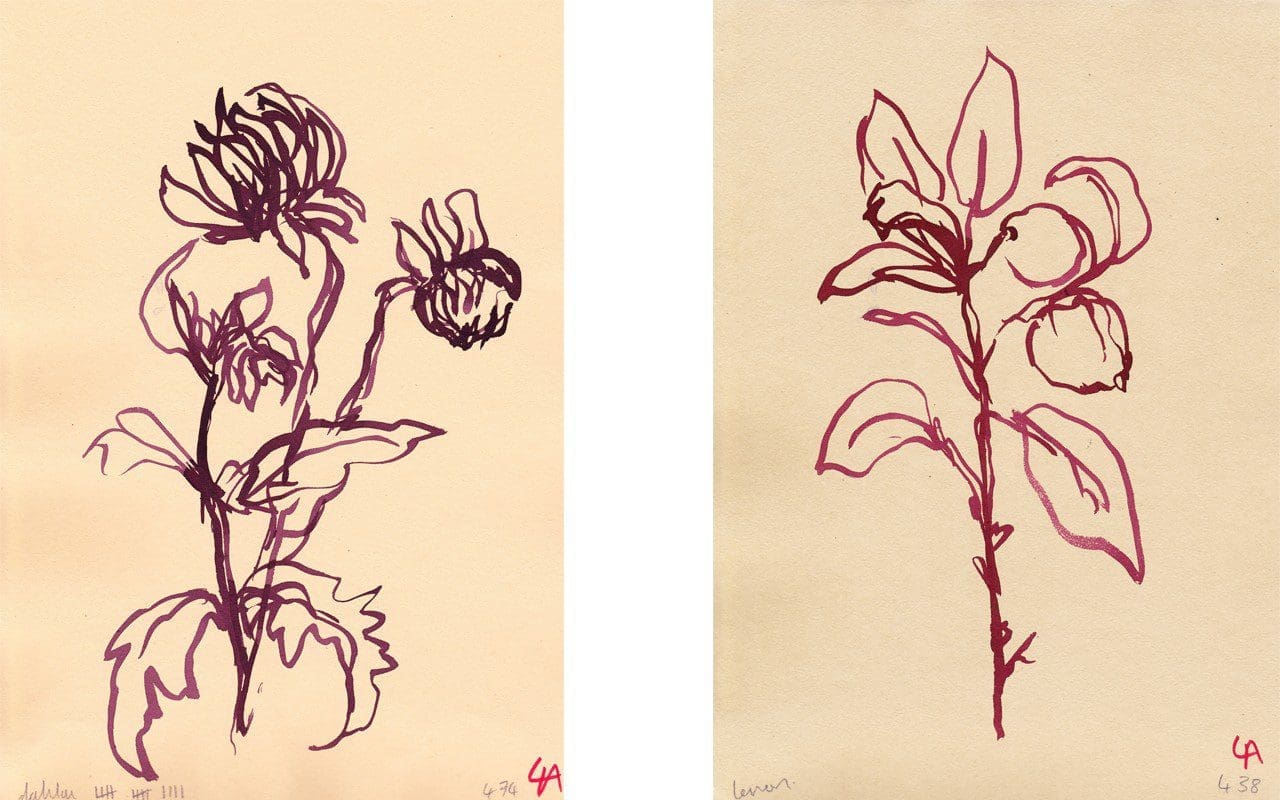

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

What does your work mean for you personally ?

Very generally it just gives me that quiet time. You don’t have to think about anything else. Once you get into a process – it’s a bit like gardening in a sense – it gives you that same mindfulness combined with productivity, which makes me feel at peace. You’re just drawing, or gardening, and that’s all you’re thinking about. And then sometimes you’re not even thinking at all, but are completely lost in the process of activity. That’s what I really love about what I do. It’s quite addictive. It empties your mind and is very meditative. I’m a worrier. I do worry too much and it’s quite nice to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to think about anything now.’ And I’ve always been quite confident in my own work, so it feels like a very safe space when I’m creating. And once I’m happy with it and happy to put it out in the world, it’s done and I can move on.

Until then – and that’s why I have my studio away, remote. I don’t want to hear everyone else’s opinions – I don’t actually show anyone my work until it’s at a certain stage, which is almost finished. It gives me a degree of freedom and escapism. Which is why it didn’t work for me as an illustrator, because someone else is dictating what you’re going to draw, your process is held ransom by deadlines, and I’ve never been any good at being told what to do. Ever. I will question and question to understand why I should do something. Just because I’m curious, but having it be just my own work I can ask my own questions and be curious about where it’s going to go next, how am I going to paint it. And I know what I am looking for, rather than what somebody else is looking for and wants me to produce. I do find it difficult when someone says, ‘I have a tree in my garden. Can you paint it ?’, because the tree might not be the thing in their garden that I would want to paint.

What are you looking for ?

In paintings I think it’s a stillness. I really want to portray stillness, or a captured moment. So everything has to be painted from life, because it feels fake otherwise. Sometimes I do draw from photos, but you’re just not capturing that moment when that leaf on that plant might have been at an awkward angle. You might not have seen that from a photo, so that’s really interesting to explore.

The 500 Flowers were all painted from life. Firstly, all near to me and around the studio, so a lot of wildflowers, but also some bought flowers, and that’s how I got in touch with Polly from Bayntun Flowers, because I looked up ‘local cut flowers’ online and saw what she was doing and I thought, ‘Brilliant !’. She had amazing heritage varieties and luckily, when I asked her if I could visit to paint, she said, ‘Yes. Come on round!’. I was like a child in a sweet shop. The first day was so exciting I must have made about forty paintings in one go. I would normally paint about five or ten. But the garden there was just chockablock with species, lots of which I hadn’t seen before, so it was very exciting and it got me up to five hundred !

But then it was hard when the winter came. I wasn’t aware of how much I would suffer. I became quite, ‘unusual’ in the winter, because I panicked and thought, ‘What am I going to draw ? Everything’s over. My work’s not good enough.’ It was really tricky. You’ve been doing all this painting and you’ve got this absolute high from painting all these things, because there are endless possibilities and inspiration in the summer, and then my first winter I didn’t know what to do. I was really looking and trying to paint winter, but really everything is just dormant and that’s when I realised I have to know what I’m going to do when winter comes. Not hibernate.

So now in the winter I paint a lot of dried leaves and stuff like that. The first winter I was so busy, doing commissions and collaborations, that I didn’t really notice. It wasn’t until winter 2016, a year after the show, that it was total panic. A flower desert. I thought maybe it was time to do some abstract stuff, get back into illustration. It was bleak. And then there was stuff going on in my personal life, and what’s going on in my personal life does feed into the work. If I’m having a grumpy day I will most likely pick out a mopy looking plant. It’s weird. I didn’t even realise it till someone else came to my studio and said, ‘This is all a bit melancholy.’ It’s frees such an subconscious part of your brain when you’re drawing, you’re not really thinking, you’re just observing. When I saw how my moods were feeding into my work I wanted to explore that more.

The paintings that I relate to the most, like Monet’s waterlily triptych, that he painted as a reaction to the war, is so powerful and emotive, and it is ‘just’ waterlilies, and I thought I would like to try and harness that emotional connection more and be more aware of it when I am working. So the tree shadows that I have been doing most recently came about because I had drawn so many flowers – I mean I was well over a thousand different flowers by now – and I was starting to fall out of love with them, even though there were commissions paying my bills. I thought, ‘I’m on the way to making myself into a performing monkey.’. I was getting set flower lists from people, with direction on paper and ink colours and I thought, ‘I didn’t start doing this to make ready-to-go flowers.’. It wasn’t me, and felt like I was heading back into illustration territory, which I had dragged myself out of.

But then it all changed because the farmer that owned the land that the barn I was renting died and so my studio tenancy went with him. I also had some financial worries. I didn’t want to paint another flower even though it was full on summer time and I was just lying in my studio taking a nap and I could see the reflections of the trees in the glass of one of my old pictures. And I thought it was interesting. I had also been experimenting with totally abstract ink paintings, which I would cut up and make into smaller single frames. But that didn’t fit in with anything that I was doing. But I started to think about how I could bring these things together. I started trying to draw the outline of the leaves onto the frame, but that didn’t look right. Then I started drawing outdoors, which I had always done. All five hundred flowers were drawn outside. But I couldn’t get a high enough outline definition.

That’s when I realised that everything moves so quickly. I would go and get my water bottle from the studio and, by the time I got back, the shadows had moved and the picture was different. That’s when I also started noticing the weather. Timing was everything. Before that I had just been aware of when each flower I was painting bloomed – this in when the roses are here, this is when the daisies look best – but not the bigger picture. When I was drawing the flowers I was more aware of the different varieties, because when you watch gardening programmes and learn that this is what a rose looks like, this is what an angelica looks like, and then when I would go out into the fields I would think, ‘Well, that has the same leaves as a rose. That looks like an angelica.’ And so then I was learning, without any books or anything, about those wild plants. Even though I didn’t know the name I was able to match them up.

What I was finding when I started doing the tree shadows was that , even when the shadows distort, they each have a particular look. Aa certain space between the leaves. The reason I like painting hazel is they have a lot of space between the leaves. I’ve tried painting quite a few different trees, but have found what works and what doesn’t work for me, for my aesthetic. I’ve also learned that, at four o’clock, you won’t be able to get hold of me, because the phone goes off, because that is the time I’ll be painting the shadows. That’s one of the things I noticed at your place. It wasn’t four o’clock. It was later. More like five thirty, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference, because that’s when you’ve got the high definition of the shadows, like on the irises that I tried doing. And where your site is so exposed the light seemed to move so quickly. I only had a half hour window, and that was it. Whereas where I am I can start at four and not finish until seven. The angle of the image changes, but at yours I was surprised at how the time made such a big impact. It’s taken months to understand that. When is the right time to draw. What is the best weather.

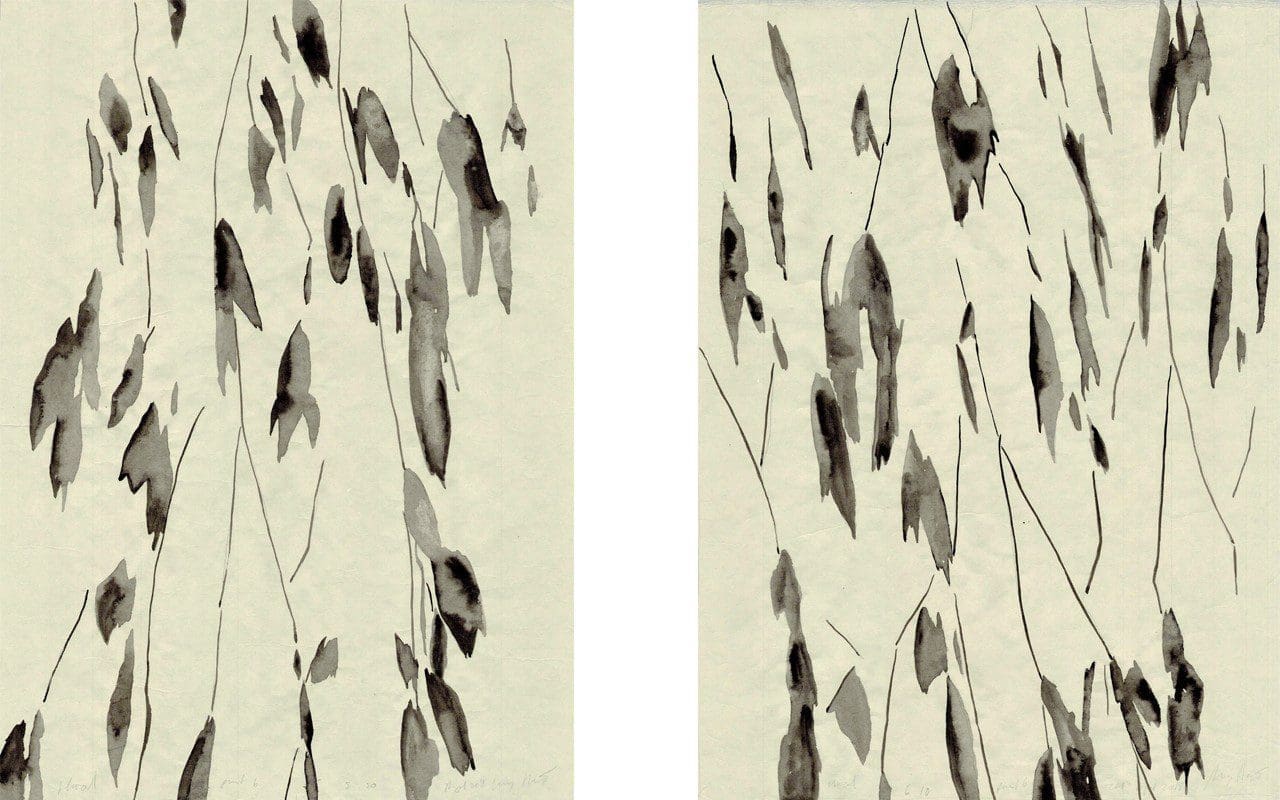

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

When did you start doing the tree shadows paintings ?

August last year. It was purely by accident. I had some leftover scroll paper and I had this birch branch and was trying to paint up into the canopy inside the studio. So I’d hung it up and then I saw that when the sun came in through the window, there it was on the ground. So I thought, ‘Oh, quick ! Get it down. Start drawing.’ I wouldn’t say that I’m drawing the outline, but more what I saw, because things move so quickly that you can’t get the exact outline, so there is a bit of interpretation involved, but I still want to be quite true to what it is, and if what it is turns out to be an awkward picture, I quite like that uncomfortableness.

So that first shadow painting, and I know this sounds cheesy, made me feel re-awoken again. I thought, ‘OK. Let’s restart.’ It was a risk, giving up on my flower paintings, which was bringing me in income, and then you think of going to your audience, who know you for your flowers, and saying, ‘I’m doing tree shadows now.’ But, the response was really, really positive. And it has been encouraging to hear people say, ‘You know I really liked your flower paintings, but I lovethe tree shadows.’

I think it’s because they feel more like art to people, whereas the flower paintings were more illustrative, the tree shadows are more abstract. But I think that doing the 500 Flowers gave me some validation, which means it is easier for people to feel comfortable with the change in direction.

When I was trying to capture a landscape through paintings of individual flowers – this is what grows here, this what I have seen and recorded – when I was in Scotland the flora there was very different, and it created en masse a very different painting. Different shapes and texture. Quite thistly, spiky plants, due to the hardier conditions up there. But not everyone got that, whereas everyone seems to get the tree shadows. I’m just really enjoying exploring it and see where it goes next.

I tried for two months earlier this year trying to capture the light coming through the canopy and it just didn’t work. Everything is a result of where I am working. My studio was too hot to work in, and so I was working under a tree – it was a walnut, which had a range of different colours in the leaves – and I was trying to capture all those variations in colour and collage them together, all in ink, in different gradients. I tried black and then green and it just wasn’t working, so I slightly felt that I was trying to – I’m always trying to come up with new work, a slightly ridiculous pressure to put on yourself, really you should just give yourself more time, so now I have gone back to doing the tree shadows. So yesterday I completed three paintings, which was a relief, because I got a bit stuck for two or three months. I do want to come back to the light through the tree canopies, because it’s been an obsession of mine for ages, since I was a kid really, when you were lying on your back on the grass looking up into the leaves with the sunlight coming through, but I can’t capture the light at the moment with the medium I’m using, so that’s why I’ve started making etchings, because the whiteness of the paper and the black ink, which becomes very matt, seems to be doing the job.

What are the challenges of your way of working ?

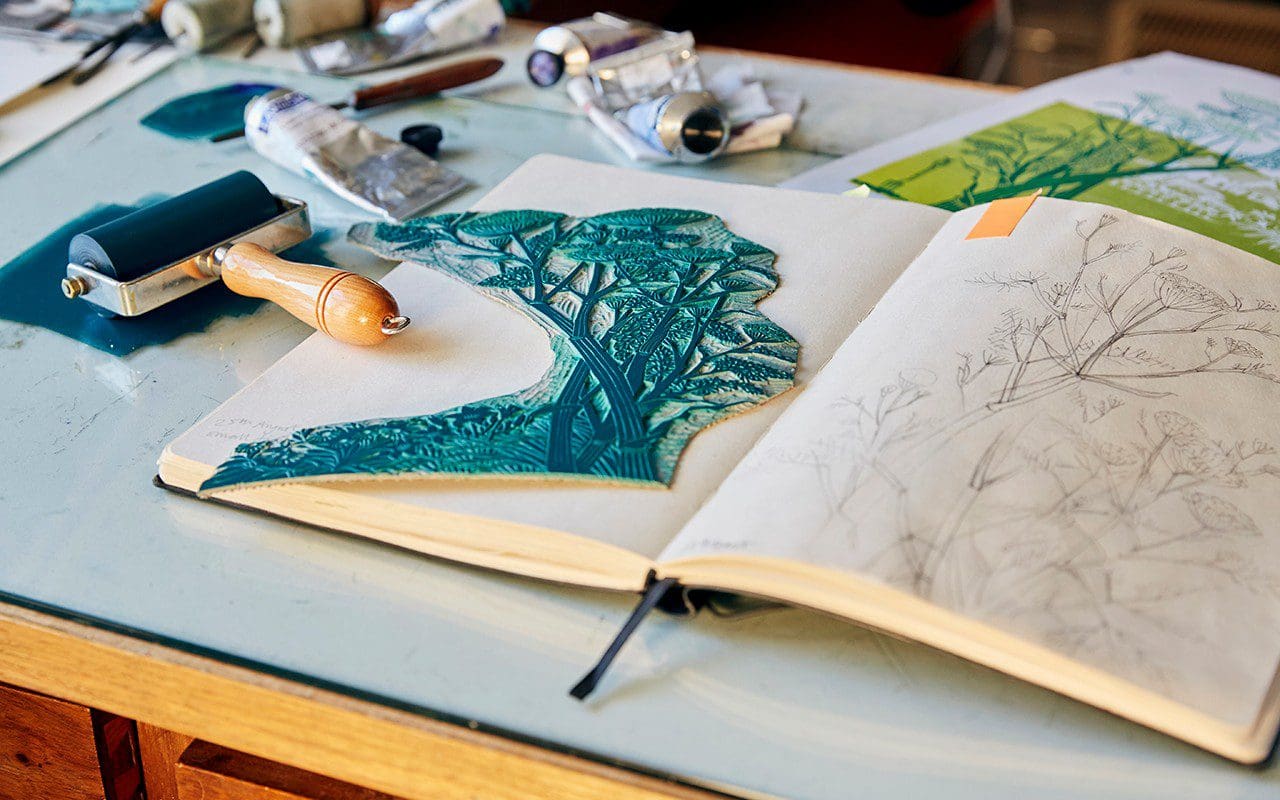

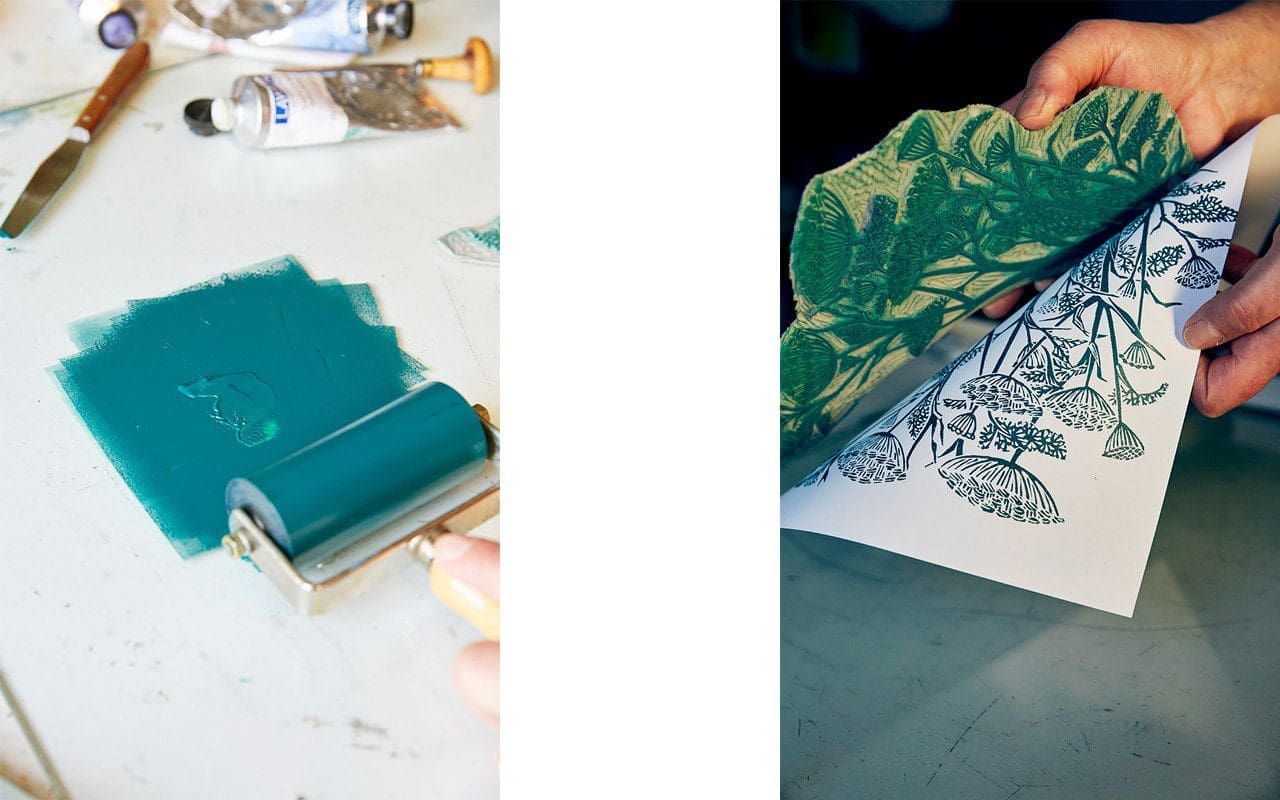

The etchings came about through the need to fill the winter gap. I was drawing in the winter sun, but it didn’t cast a good shadow, which I hadn’t realised, because the angle of the sun was too low. And it was a really grey winter last year, so I was waiting for the sun that never came. I did try using a lamp in the studio, but it felt wrong. It was impossible to get the light at the right angle and it felt like faking it. I am interested in capturing an ephemeral moment, not a frozen moment that doesn’t change. I have tried working from photos of shadows I’ve seen when out and about and projecting them onto the wall of the studio, and again it just didn’t feel right. I wasn’t capturing that moment that the camera had captured. And I enjoy the process of being really spontaneous. Just yesterday I had a small window to work in because the clouds were coming, and I was moving around this mock orange branch, and then the sun went, which was my fault for taking too long, which takes me back to that whole thing of not thinking and just being in the process. Every time I overthink it, it feels like I could be on that painting for weeks, and I’m not really like that as a person, so it would feel unnatural to do that.

By working with the sun I have got to know more about the passing of time, changes in daylight and seasonal changes. So I now know that autumn is coming up to peak season, because you get those amazing long shadows, which I find quite exciting, alongside the anxiety of knowing that I’m running out of time. I did do some painting in Thailand last winter. Paintings of palm trees that just looked like palm trees, and I found that quite interesting, because I didn’t know the Thai landscape, I didn’t know Thai plants, and I realised I am happier painting the familiar. Someone asked me recently why I paint hazel, and it’s simply because it’s in the hedge at the back of my studio, and it’s abundant. When I came to your place, again it was just complete overstimulation. There was so much, and I didn’t know what to choose, and your garden is very much a changing landscape. You can leave it for two weeks and come back and there will be a whole different colour palette. So when I came to your garden it just felt wrong not to paint flowers, even though in my mind I thought, ‘No more flowers. I’ve painted enough.’ It was the first time I felt like I actually wanted to paint flowers again, because I was discovering new things again, So that is something I’d like to explore more in your garden, but I need to get more used to it, as it is a whole new territory.

You told me that painting in our garden has opened up a new way of working for you. How ?

Well, the summer we’ve had this year has been very unusual. We don’t usually get weeks on end when it is just sunny every day, and I just felt like I needed to mark that. To capture the sun, and capture the flowers. So I thought, ‘How can I do that ?. So what I have noticed about your garden is that it has a lot of different shapes. All the plants have their own identity, and they all hold their own in the beds, none of them get lost. So I wanted to capture the shape of the plants, but not in ink.

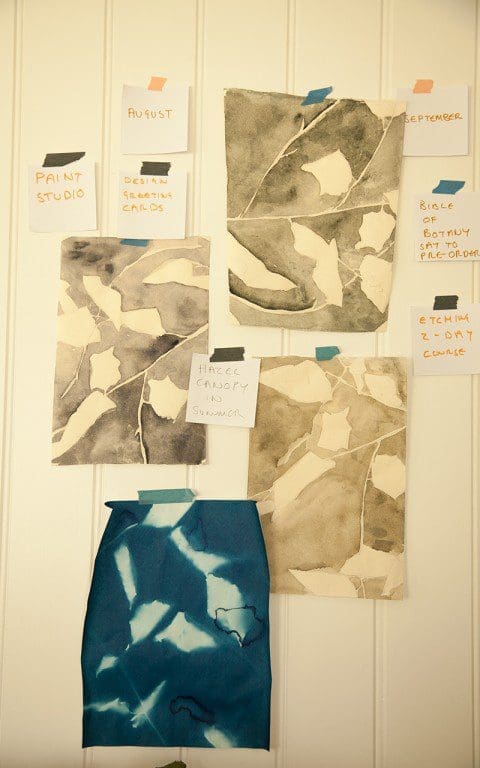

With the etchings I did last winter of leaves, you just got the silhouette, and so I tried painting the silhouettes of some of your plants directly from life, and I just didn’t like the feel of them, and then the light was so amazing that that became my focus. So I started exposing the shadows onto cyanotype paper, where you are directly capturing the light on the paper. I’d first done this a few months earlier and was really interested in the process, as it produces images that are almost like abstract paintings. In some you can tell what the plant is, but in others you can’t and I like that. So the first time I tried it in your garden I was too scared to get close to the plants in the beds, and so I took the deadheaded rose cuttings off the compost heap, because I could just put them onto the paper and allow them to fall in their own way without me arranging them. I also like that element of chance. And I was also very influenced by the things you have at your place. Quite a lot of elements from Japan, a lot of natural materials and a lot of craft. And I just felt that etching, which is a craft, was a more appropriate response to the site.

So I want to create a series from your garden, but I would also now like it to be a longstanding, seasonal thing. So this summer it has, so far, been about the roses, which were such beautiful, old-fashioned looking varieties. I would like to come back at harvest time and see if I can capture that, when everything is going to seed. And rosehips. I just really want to document the seasons, as I don’t think people look at things closely enough and I think, when you’re more in tune with the seasons, you understand the world and our place in it better.

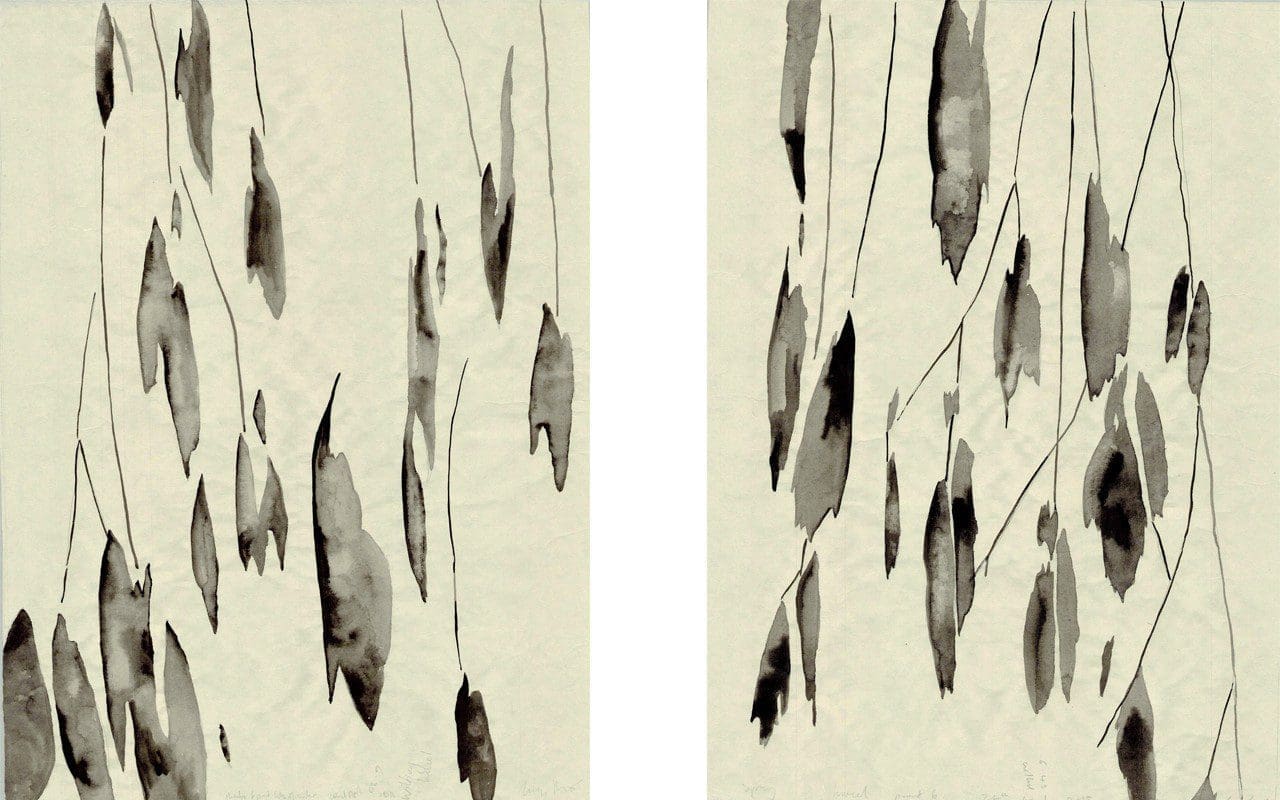

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

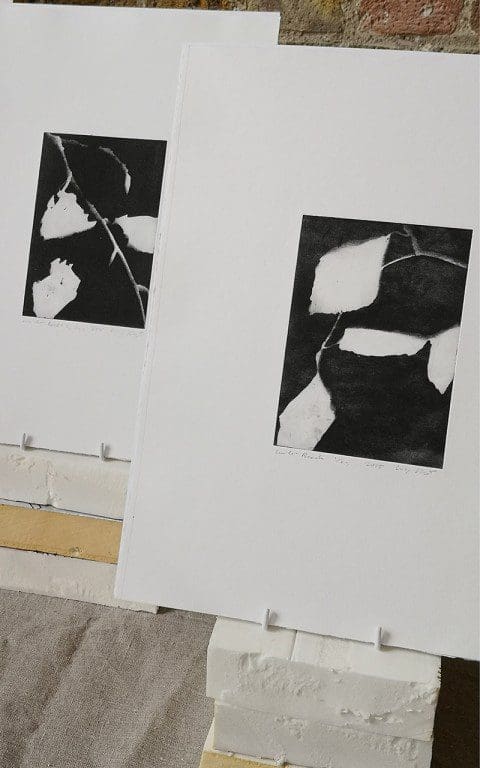

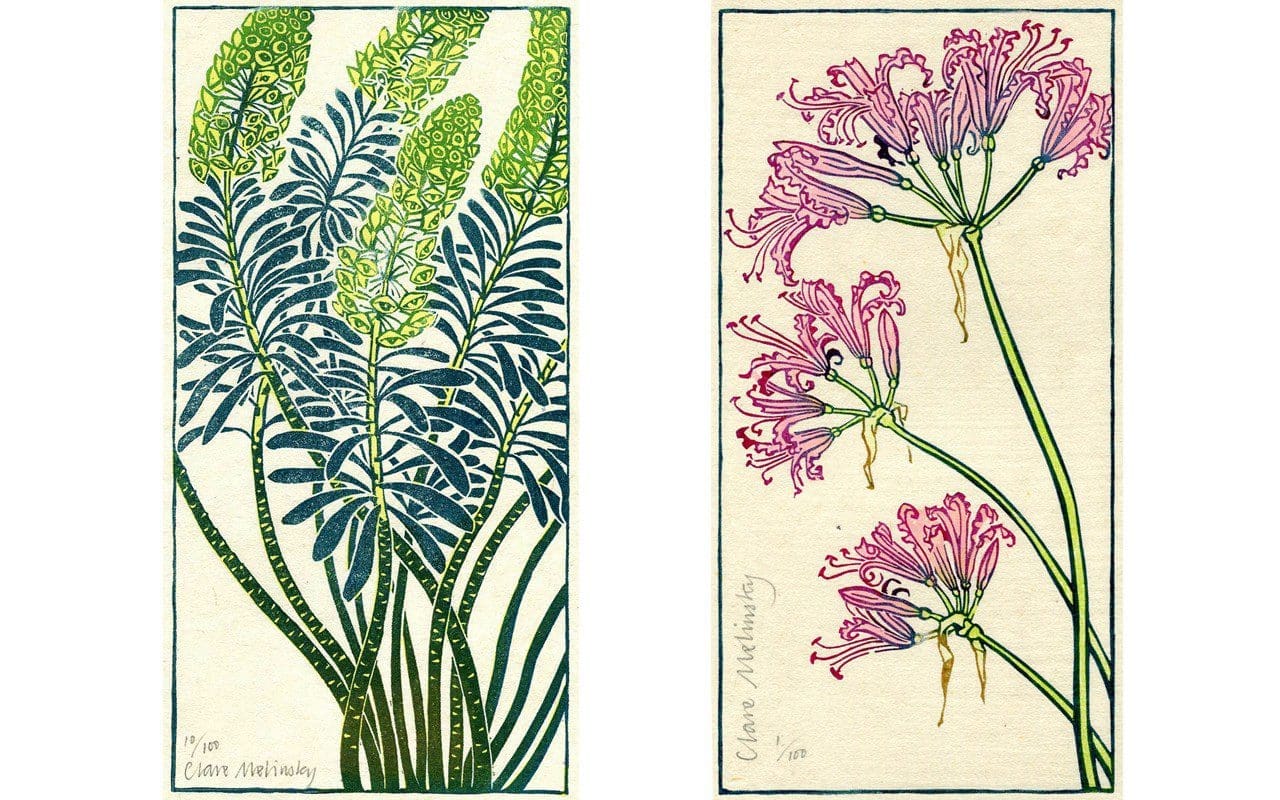

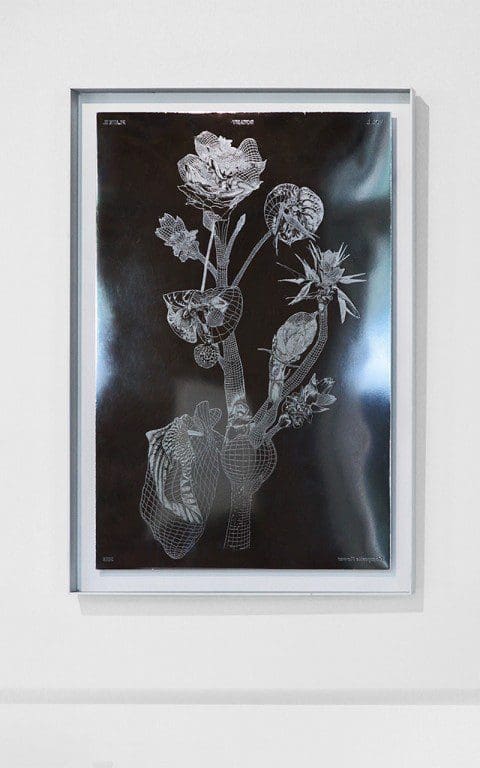

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

After last winter do you have a new approach for this coming winter ?

Yes, winter will be the time when I execute all of the etchings I am going to make from the cyanotypes taken in your garden. The process of creating etchings is quite time-consuming and complex, and it is still very new to me so I would like to spend more time getting more experience of that process. So at the moment I am just amassing lots of exposures so that I have plenty to work with later. And I am also going to explore some light and dark paintings of your garden from sketches I have made. Fingers crossed I am beginning to find a good seasonal rhythm for my work.

I’m also going to experiment more with photography, and explore the uses of light more and see where I can take it. As well as stillness I’m really interested in capturing the passing of time. For example the cyanotypes I made in your garden only needed a ten second exposure because the light is so strong there, whereas in my studio I need a fifty second exposure to create the same quality of image, but that longer exposure also captures that extended amount of time. I find that fascinating, and a route I’d like to explore. I also go to Westonbirt Arboretum in the winter, as there is always something out. Going there makes you realise how much there is to look at. There’s always something in season, or that has something in its branches to explore, and then you really are looking at winter. But I think your garden has a lot of winter interest, which I am looking forward to.

I also want to focus on the work without the pressure of a show, and just have a process for a while and see where things go, like the exhibition at the Garden Museum, who you introduced me to, and which came about very organically. I would like to be a bit more relaxed and take more time.

Do you have any burning ambitions for projects ?

I would love to be commissioned to create a stained glass window in a church. I’m not religious, but because I work so much with light, I could really see my work translating into stained glass effectively, with sun streaming through. I’d love to work with a craftsperson to do that. And I’d really love to create a design for the Chelsea Flower Show poster, which has always been something I’ve wanted to do. And I would love to do a residency in Japan.

Lucy’s work is available to buy from a catalogue on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs of Lucy and studio: Huw Morgan. All others courtesy Lucy Augé.

Published 25 August 2018

I first encountered Beth Chatto in 1977 at The Chelsea Flower Show. It was the first time she had exhibited and, aged 13, it was also the first time I’d attended the show. I remember quite distinctly the spell that was cast when my father and I came upon her stand. The froth, confection and sheer horticultural bravado that made the show remarkable fell into the background, and suddenly everything was quietened as we stood there, entranced.

We worked the four sides of the display, noting the differences between the plants that were grouped according to their cultural requirements. Leafy woodlanders cooled the mood where they were mingled together, with barely a flower, in celebration of a green tapestry. Nearby, and separated by plants that allowed the horticultural transition, were the delicate blooms of the Cotswold verbascums, ascending through molinias and sun-loving salvias. Plants with none of the pomp of the neighbouring soaring delphiniums, but which were captivating for their modesty and feeling of rightness in combination. The exhibit stood apart and was confidently delicate. We learned from it, filling notebooks hungrily with sensible combinations, happy in the knowledge that the wild aesthetic we were drawn to was something attainable.

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

At that point no one else was doing what Beth was doing and, when I met Frances Mossman, who commissioned me to make my first garden five years later, it was those show stands that brought us together. We talked at length about Beth’s ethos, the excitement of combing her catalogues of beautifully penned descriptions and our resulting purchases.

Of Crambe maritima, she wrote, “Adds style and grandeur to the filigree grey and silver plants. Waving, sea-blue and waxen, the leaves alone can dominate the border edge, while the short stout stems carry generous heads of creamy-white flowers in early summer. The stems are delicious, blanched in early spring, served as a vegetable. 61 cm.”

While Gladiolus papilio is, “Strangely seductive in late summer and autumn. Above narrow, grey-green blade-shaped leaves stand tall stems carrying downcast heads. The slender buds and backs of petals are bruise-shades of green, cream and slate-purple. Inside creamy hearts shelter blue anthers while the lower lip petal is feathered and marked with an ‘eye’ in purple and greenish-yellow, like the wing of a butterfly. It increases freely. Needs warm well-drained soil. 91 cm.”

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima

Crambe maritima

We came to rely upon her nursery of then ‘unusual plants’; me with a long border I had planted in my parents’ garden, and Frances with her own first garden in Putney. Unusual Plants was the place we would go to help us make that first garden together and, when we started making the garden at Home Farm in 1987, it was Frances who wrote to Beth to tell her of her positive influence and of what we were doing there to make a garden without boundaries. Beth wrote back with careful responses and encouragement. Once I had got over my shyness, I too started to write and we struck up a friendship from which I will always draw inspiration and refer back to as pivotal in my own development.

Beth made an indelible impression with her words, wisdom and practical application of good horticulture. In this country she was arguably the link back to the beginnings of William Robinson’s naturalistic movement and an informality that drew inspiration from nature. Her writings were always dependable and combined the artistry of an accomplished planting designer with the fundamental practicality of someone who had seen how plants grew in the wild and knew how to grow them to best effect in combination in a garden.

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

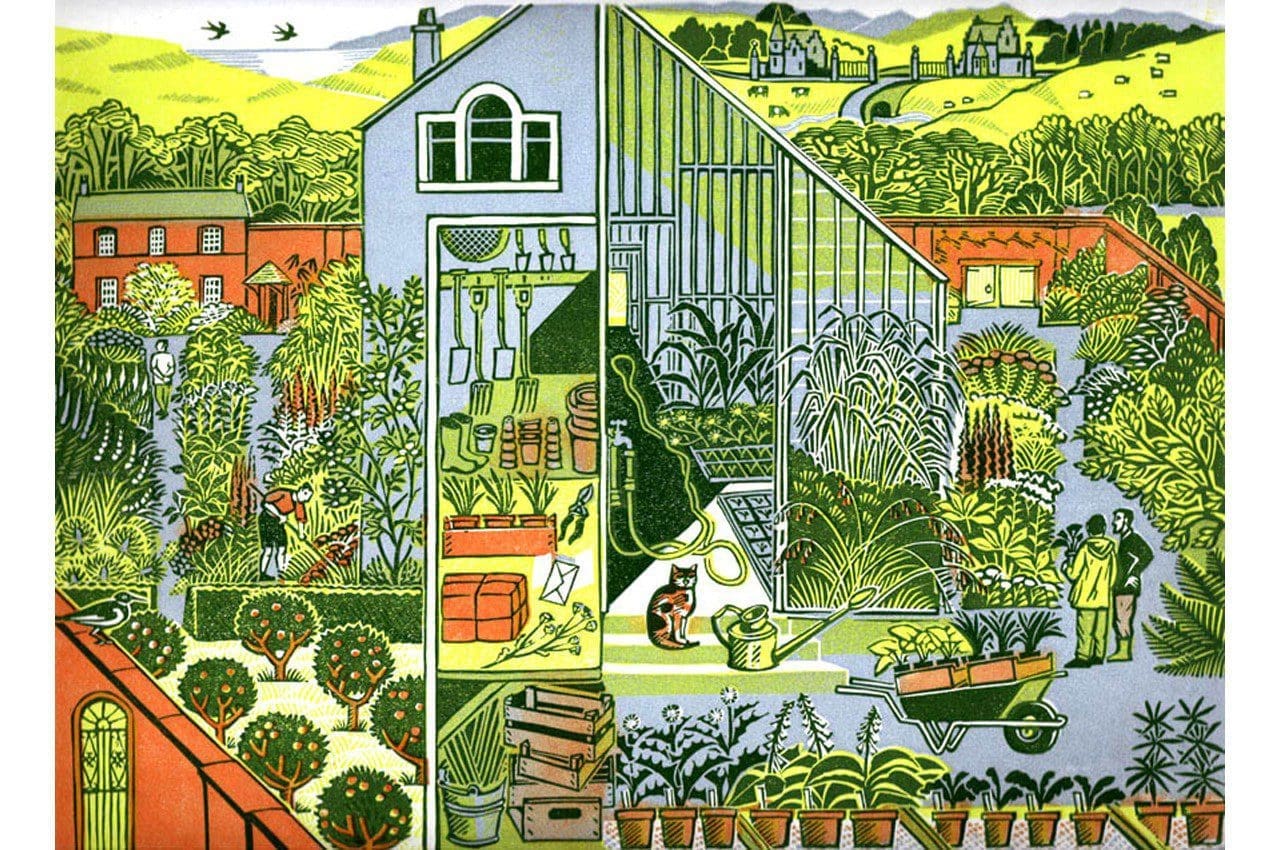

If you study Chelsea today, it is easy to overlook the influence she had on the industry of nurserymen and designers. The ‘unusual plants’ that were her palette are no longer so, and the way in which they were combined naturalistically on her stands has become the status quo. Rare now are the perfect bolts of upright lupins and highly-bred, colourful perennials, not so the mingled informality of plants that are closely allied to the native species, many of which had their origins at her nursery.

Though we will all miss her presence after her sad departure last weekend, her influence will remain strong. In the hands of Beth’s trusted team, led by Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg, the gardens and nursery have never been better. In recent years, as Beth’s health has deteriorated, Julia Boulton, her granddaughter, has firmly taken the reins and, as well as ensuring that the gardens and nursery continue into the future, has been responsible for setting up the Beth Chatto Education Trust and, this year, a naturalistic planting symposium in her name which takes place in August. At its heart the gardens will become a teaching centre, a living illustration of Beth’s passion for plants and her ecological approach to gardening.

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

Looking around my garden this morning, I can see Beth’s influence almost everywhere in the plants that are grouped according to their cultural requirements. Be it the ‘pioneers’ in the ditch, which have to battle with the natives, or the colonies of self-seeders I’ve set loose in the rubble by the barns, her teachings and plant choices are everywhere. Her plants also connect me to a wider gardening fraternity, a reminder of her generosity and willingness to share. The Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum that has seeded itself around the vegetable garden was first given to me by Fergus Garrett as ‘Beth’s Poppy’, since she had passed on the seed, while the Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ growing against the breezeblock wall by our barns, was collected by her great friend, the artist and aesthete, who helped open her eyes to the beauty of plants.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

A visit to the nursery is still one of my favourite outings. I can guarantee quality and know that I will find something that I have just seen growing right there in the garden and have yet to try for myself. About twelve years ago, on a trip that culminated in a full notebook and an equally full trolley, Beth gave me a plant of Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’ accompanied with the usual words of good advice about its cultivation. Sure enough, it is a good plant both in its ability to perform and in terms of its elegance. I moved it carefully from the garden in Peckham and divided it the autumn before last to step out in an informal grouping in the new garden. Last Sunday, although I did not know that this was the day she would finally leave us, the first flower of the season opened. As is the way with a plant that has a heritage, I spent a little time with her, pondering aesthetics and practicalities. I know for certain that it will not be my last conversation with Beth.

Beth Chatto 27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 May 2018

In March, the week after my mum died, we received an email from Simon Bray, a Manchester-based photographer and artist, asking if we might be interested in featuring him and a new book he was self-publishing. The book, Signs of Spring, is a collection of family photographs he has assembled of his childhood garden, which was initiated in part by the death of his father, and the importance the garden had in Simon’s memories of him. Although it was pure coincidence that Simon chose to write that week, it felt as though I was being offered an opportunity to remember mum in a new way. The more of Simon’s work I saw, the stronger this feeling became.

Simon, can you tell us how you came to study and work with photography ?

I began taking photographs when I moved to Manchester from Winchester for university. It was quite a shift for me, having lived in rural Hampshire my whole life, so I would walk everywhere, exploring the city by foot. Taking pictures helped me assimilate. I’ve never actually studied photography. I studied music, but as a drummer, so taking photos was something I could do on my own without requiring others and the practicalities that come with playing drums! Photography became one of many ways in which I like to express myself creatively and I’m now very fortunate to call it my job, making time for both artistic projects and commercial work.

You have a clear interest in place as a locus for memory. How did you come to realise and key in to this aspect of photography ? Has the idea of loss always been intrinsic to your work, or is it something that has developed over time ?

The notion of place has always been central to my practice. As I mentioned, Manchester was a starting point, but photographing places such as The Lake District helped me to understand that there was something about taking photographs in certain locations that excited me and made it easier to express myself. This has led me to explore my own connections to physical places and also work with others to explore theirs. It’s not always somewhere grand and romantic like the lakes, the garden from my family home has probably been the most significant place in my life and where I took many photographs.

The notion of loss came into my work after my dad passed away in December 2009. It took me quite a while to pick up my camera after that, nothing seemed significant enough to make pictures of but, over time, I began to appreciate that my photography could actually be hugely beneficial in helping me to express how I was feeling.

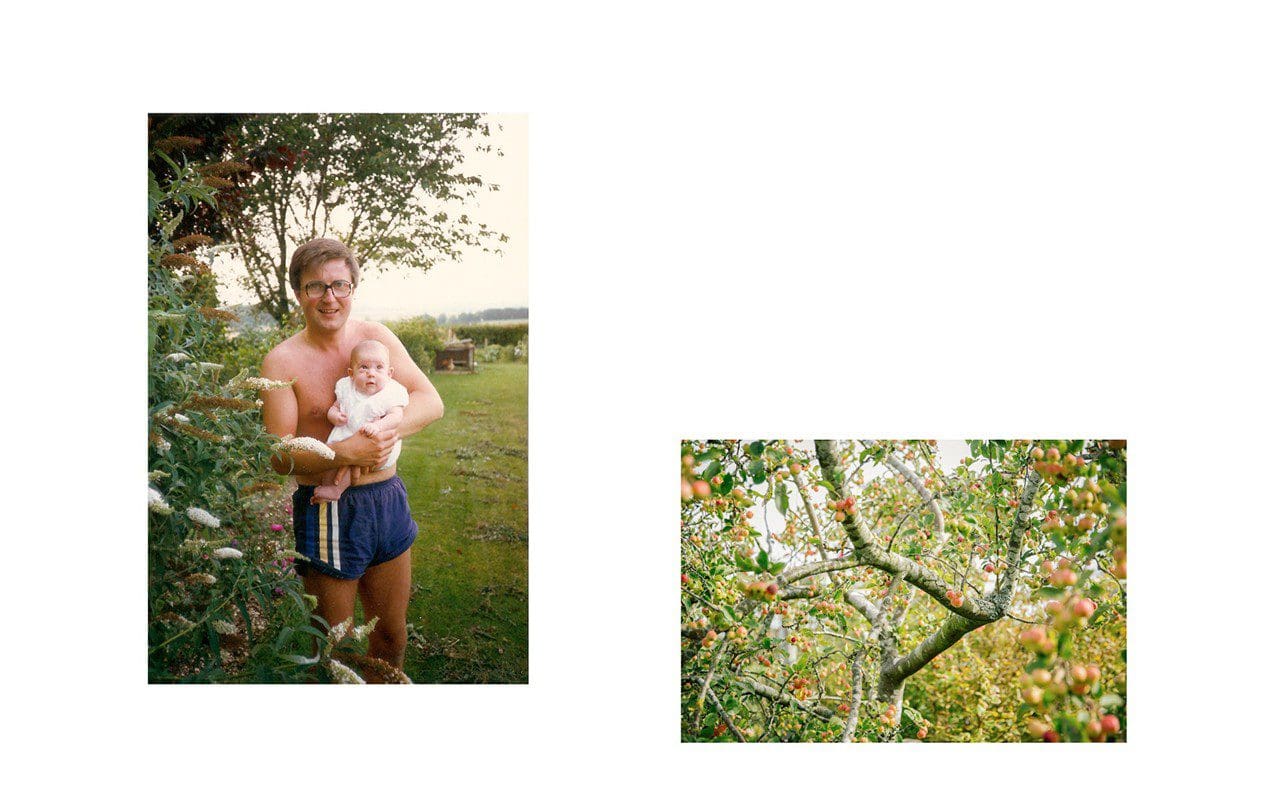

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

I was really moved by Signs of Spring, the book you have published in memory of your dad. Also your ongoing photography project 30th December which is also connected to memories of your father. Can you tell me how each of these projects came about, what they mean to you and what they provide for you ?

Both of those projects are about place, memory and loss, manifested in different ways. Signs of Spring is a collection of photographs that I’ve gathered together, found in family photo albums. It’s not a memorial as such, more a celebration of the life of our family in the garden where I grew up. Dad was a very keen gardener, having grown up on a farm in Cornwall he spent every hour of a daylight outside, producing vegetables and fruit and keeping everything very well maintained. It was a playground for my sister and I and the location for countless family occasions, so it holds many special memories for me. After dad passed away, mum vowed to keep the garden going, which she did very well, continuing to produce fruit and veg, but a couple of years ago she decided it was time for a fresh start and moved down to Penzance. That meant having to say goodbye to the house and garden I’d grown up in, which was far harder than I’d imagined. It felt like having to let go of Dad all over again, so I wanted to celebrate the garden by producing this book.

The 30th December project is very similar actually. It’s the anniversary of dad’s passing and, once I’d picked up my camera again, on each anniversary I’d go out and make pictures. Last year I made a series of handmade books with photographs taken at dawn on St. Catherine’s Hill in Winchester, somewhere we used to go as a family. The pictures aren’t necessarily about loss, they’re not inherently sad pictures, but it’s a process that helps me remember and engage with how I’m feeling on that day. I shall keep on making photographs on 30th December each year, wherever I am in the world.

Photographs from 30th December

Photographs from 30th December

I am interested in how you see gardens as a receptacle for childhood and family memories. Can you tell us your thoughts about this and how gardens differ from other landscapes, both urban or rural ?

Unless you’re a farmer, your garden is a patch of the world that you’ve been gifted to take care of. You can do with it as you please, you can pave it over and not have to think about it, or you can cultivate it to feed your family, create a place to relax and share with others, or fill it with flowers for others to see and enjoy. There’s something very satisfying about a well-maintained front garden! It’s the sense of ownership and responsibility that makes it differ from urban and rural spaces, not that you can’t feel ownership of the town you live in or your favourite national park, but those are shared spaces, your approach differs to that of your own garden. I’ve recently moved to my first house that has a garden and I’m getting so much pleasure from looking after it. Simply just staring out the window at the birds feeding as I write this is making me feel relaxed!

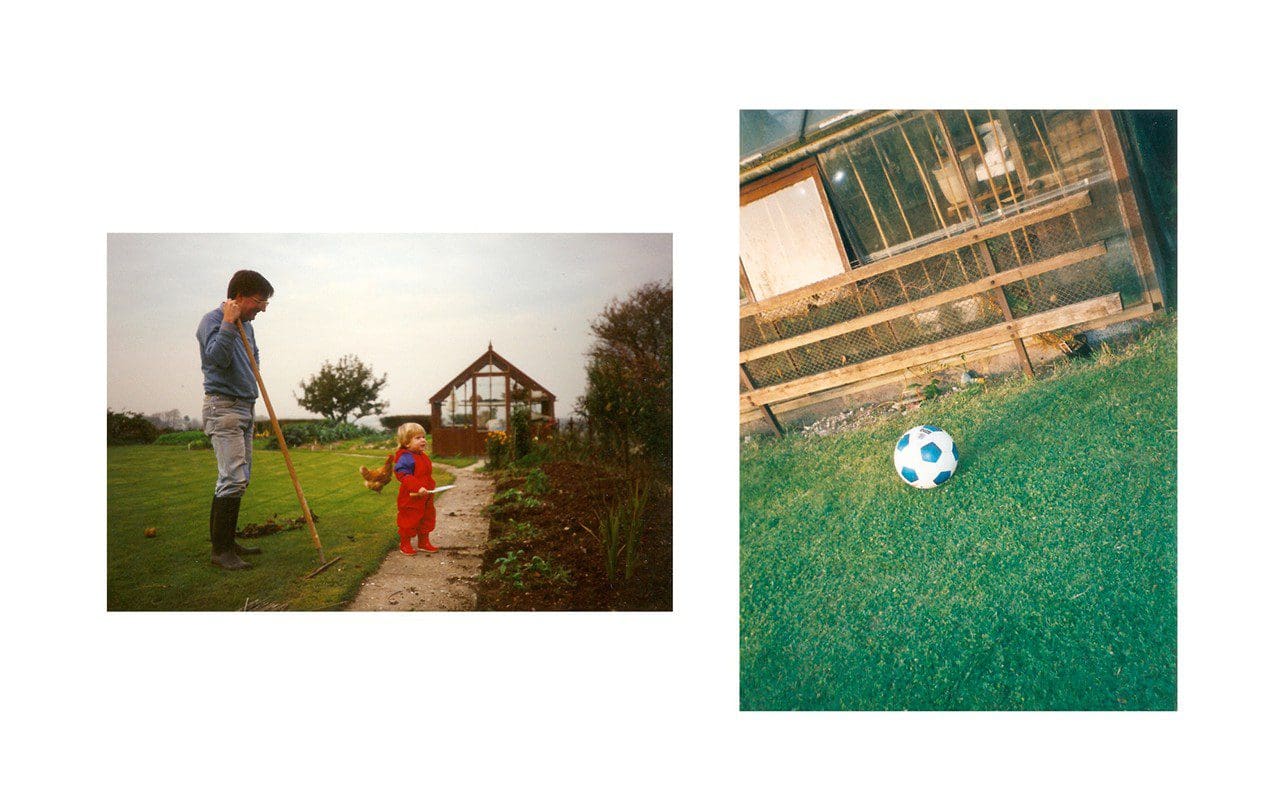

Spreads from Signs of Spring

Spreads from Signs of Spring

The Loved&Lost project looks at a wide variety of places through the prism of loss, memory and the passing of time. I found it very cathartic reading about other people’s experience of losing a loved one. Can you tell me more about how the project came about and what you learnt from it ?

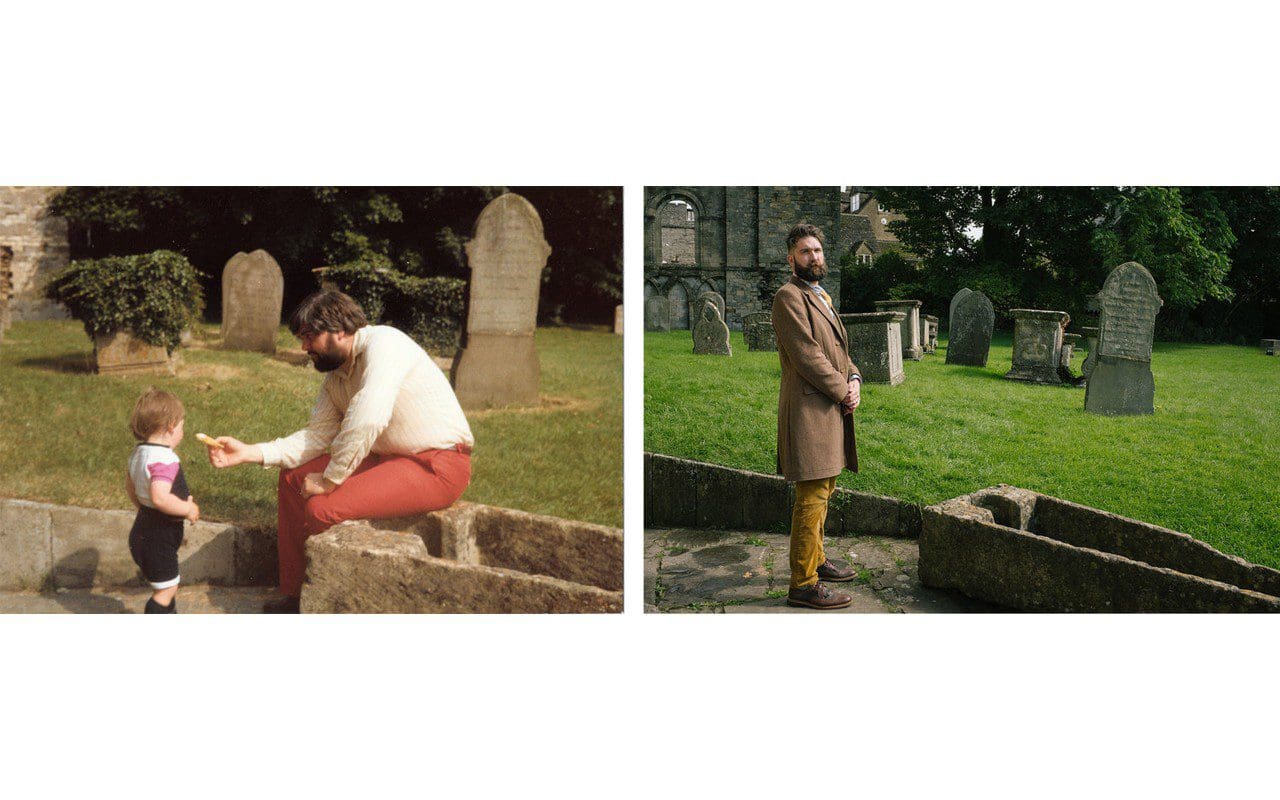

As I alluded to earlier, after the loss of my father I found ways to try and help others engage with their loss, and this now manifests itself as the Loved&Lost project. I invite participants to find a family photograph of themselves with somebody who is no longer with us, we then return to the location of the photograph to re-stage it and record a conversation about the day. It’s amazing how impacting it is to return to the physical location of the photograph. It brings back so many memories and makes it all very tangible for the participant. I want to encourage them to engage with their loss in a different way. The photograph is simply a starting point, but the process allows us to have a conversation, to recall the day the first image was taken, to share their account of losing someone close to them, but also celebrate the person who is no longer here.

When dad passed away, lots of people asked me how I was, which is a very kind and natural thing to do, but in the mix of it all, I didn’t actually know the answer to the question and so I didn’t really want to talk about me, what I wanted to talk about was dad. I found myself in social situations recalling memories, jokes, anecdotes that he would have enjoyed, but not really being able to share them because there was no context for everyone else, so I wanted to create a forum in which it’s absolutely fine to share your favourite stories about that person that no-one else knew quite like you did.

The project is ongoing, and I learn something new from every person I meet. It’s not about having to be strong or getting over it after a certain amount of time – some people take part months after their loss, others many many years – the loss is still there, but how you engage with it varies. Lots of people end up restructuring their lives after a significant loss, your focus changes and priorities get realigned, it shapes you, not always in ways that you understand in the moment, but over time I find that most people feel it’s important to know that some good has come out of their pain, and for me, I’d like to think that Loved&Lost is that.

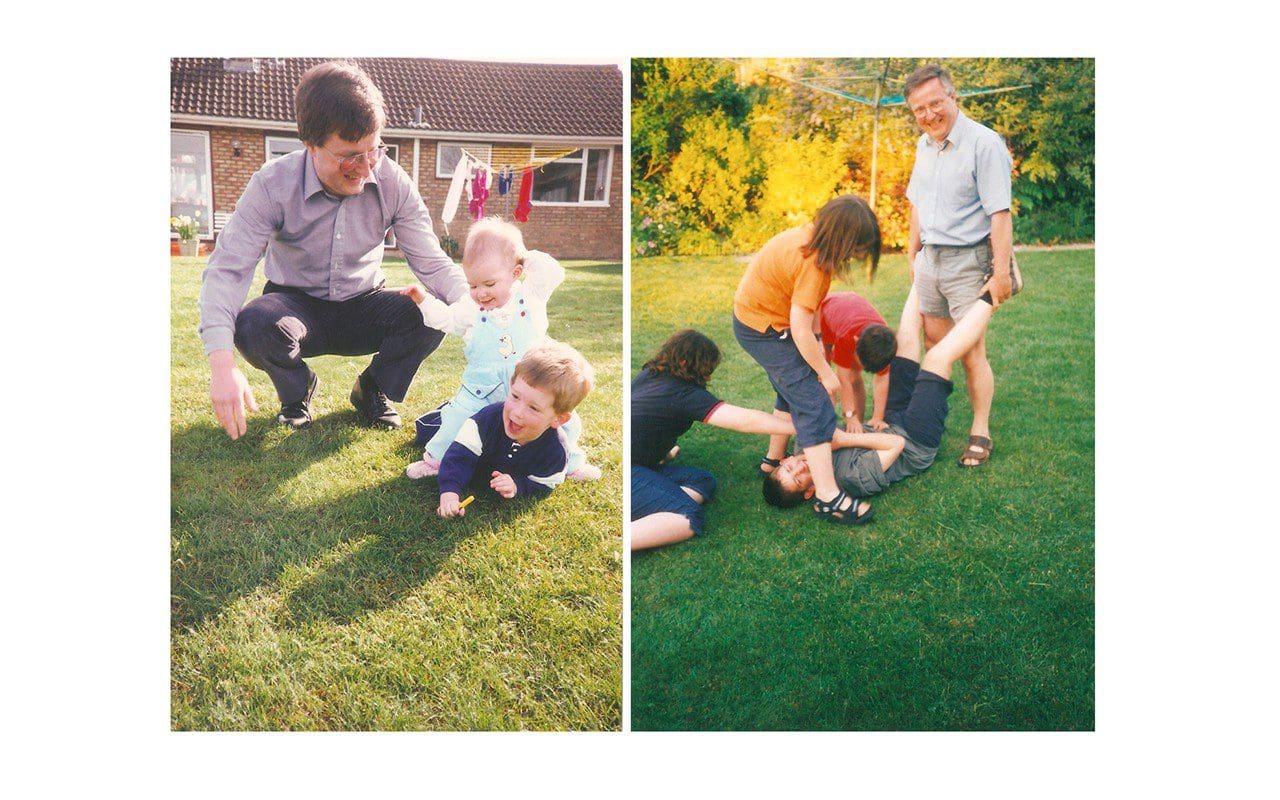

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

Double portraits of Paul, Emelie and Will from Loved&Lost

Much of your landscape photography has a very particular atmosphere of emptiness or vacancy, like stage sets where the protagonist has just left or is just about to arrive. Can you explain your feelings about ‘wild’ landscapes and how we relate to and inhabit these environments ?

I really like that analogy, because as much as the landscapes within the UK especially can be wild, most of them are fairly approachable as well. Obviously you need to be cautious and equipped according to the weather, but there are so many accessible and varied locations within these British Isles that can be truly breathtaking. So many of us use the outdoors as a means of escape. I will always feel better about life if I’ve spent the day outside, particularly in some mountains or by water, so it feels very natural to be drawn towards that as subject matter photographically. I quite intentionally don’t include people within my landscape photographs. In fact, sometimes there’s not much of anything in my work, probably just sky and mist with a bit of land at the bottom of the frame! I think that’s a result of my yearning for space. My mind seems to be full of thoughts and ideas all the time and stretching my legs and exploring somewhere new seems to not necessarily turn that off, but brings clarity and energises me mentally. The space required for that comes through in my images, which sometimes can appear bleak or vacant, but I suppose it’s a thoughtfulness or consideration that gets subconsciously built into the photographs.

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

Photographs from Simon’s ongoing Landscape series

How did the The Edges of These Isles project come about and how did you collaborate with artist Tom Musgrove on it ?

Working with Tom came about after we did the Three Peaks Challenge together with a couple of friends. We established that we’d both like to be making more work inspired by landscape and that it would be very interesting to see how a painter and a photographer might be able to collaborate. It took us a couple of years, but we ventured all across the UK together, making work, sharing thoughts, ideas, music and establishing where our approaches to making work could meet and where they differed. We ended up making a 120 page book, a 25 minute film and have exhibited the work 3 times. It was a huge step forward in terms of my appreciation of what it means to be an artist and how I can engage with the subject matter before me and utilise it to express myself. The work I made on those trips is still some of my favourite that I’ve created. I’m a romantic at heart, so the aesthetic and notion of the sublime are very much in my mind when I’m working within the landscape, but I also want to bring myself into the image. I like to do my best to avoid making pictures that I know have been captured countless times before by awakening my senses in that moment to really understand how I’m going to make that picture, which is something I learnt from Tom.

What can you tell me about your involvement with One Of Two Stories, Or Both (Field Bagatelles), the piece by Samson Young that was commissioned for the 2017 Manchester International Festival ?

I was fortunate to be selected as one of six artists to take part in a fellowship with Manchester International Festival last year. This involved being placed within one of the festival commissions and I was very lucky to work with Samson Young, who had just represented Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale. It was incredible to see him at work, creating a 5 part radio play complete with live musicians, voice actors and foley artists, as well as constructing an installation for the Centre For Chinese Contemporary Art in Manchester. He invited me to play drums in the radio pieces and make a photograph for the installation, both of which were a huge privilege. I also got to engage with the other young artists and experience many other performances within the festival, which really broadened my horizons in terms of what I create and who my audience is. Not that I have the answers for those things yet, but it was a hugely inspiring experience.

Samson’s piece was all about the hypothetical journey of Chinese migrants to Europe at the start of the century travelling by train. It was amazing to observe how Samson created that world through the medium of radio, utilising the music, actors and created sounds. It formed amazing visual landscapes in my mind and really informed how I engaged with the characters in the piece. It got me thinking about how I construct the landscape images that I make, how much of it is me simply photographing what’s in front of me, and to what extent do I build the feel and atmosphere of an image in how I shoot and edit it.

Photographs from The Edges of These Isles

You are currently working with Martin Parr on a new commission for Manchester Art Gallery. Firstly, I’d love to hear your take on Martin’s photography and what it means to you. Then can you then tell me anything about the work you’re collaborating on?

Martin was one of the first photographers I was ever made aware of, and there’s something about his style which is so stark, but so honest at the same time and his sense of humour is something I know I’ve tried to seek out in my street photography work as well. I’ll see one of his images and know straight away that it’s his, which, as a photographer, is something I’ll always be aspiring to.

I began working with Martin in March as the producer for his commission with Manchester Art Gallery for an exhibition opening this November. The gallery is going to show a huge selection of Martin’s Manchester work from the past 40 years, from when he studied here in the early 70’s up until today, which is what we’re currently working on now. So I’m spending a lot of time arranging shoots, but then I get to work alongside Martin for a few days at a time and it’s a real privilege to observe him working, he’s so confident and assured, just being around him for a few days fills me with confidence.

And finally, what are you working on personally at the moment, and are there any opportunities for us to see your work anywhere ?

I have a couple of exhibitions coming up, the first is Duality, a documentary project that I’ve collaborated on with another Manchester photographer. Its focus is workwear and uniform, posing questions about how we perceive the individual based on their appearance, which they potentially haven’t chosen for themselves, but also how the individual perceives themselves based on what they’re wearing. That’s going to be on show at The Sharp Project, Manchester on 31st May.

I’m also showing a selection of stories from Loved&Lost at Oriel Colwyn in Colwyn Bay throughout July. It’s the first time the work will have been shown in a gallery, so I’m currently establishing how to do that sensitively and effectively.

Working with Martin and finishing off the Loved&Lost stories is keeping me fairly busy at the moment, but I have begun work on a couple of new projects, one inspired by the locations that feature in Brian Eno’s album Ambient 4 : On Land, and the other is about photographing smells, which I know is impossible, but I’ve just started developing the idea to see if it’ll work!

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs: Simon Bray

Adam Silverman is a potter living and working in Los Angeles. After initially studying and practising as an architect, in the early 1990’s he was one of the founders of cult skate wear company X-Large. Since 2002 he has been practising as a professional potter. As a keen amateur potter myself, two years ago I was inspired to write him a fan letter and was delighted to receive an email from him inviting me to visit him at his studio, which I did in October 2016. Adam generously gave me two days of his time, showing me his studio, his work and explaining his process. This March he has his first European solo exhibition in Brussels at Pierre Marie Giraud.

Adam, how did you come to work in ceramics ?

Ceramics is something that I started as a hobby when I was a teenager, around 15 or 16. Before that I did wood turning and glass blowing. Clay stuck and I continued taking classes as a hobby throughout high school and college. In college I studied architecture, but took ceramic classes whenever I had a free period. I never studied it per se just enjoyed doing it. I didn’t know anything about making glazes or firing kilns or the history, ancient nor modern. I continued making pots as my creative outlet after college and while I began my working life in Los Angeles, first as an architect and then as a partner in a clothing company.

In about 1995 I bought a small kiln and a wheel and set up my own studio in my garage at home and the hobby grew into more of a passion and then into a fantasy life change. In 2002 I attended the summer ceramics program at Alfred University in upstate New York with the intention of studying ceramics seriously for the first time. I wanted to learn about glazing, firing, history, etc. and to see what it felt like to work on ceramics full time, 8-10 hours a day, in a serious studio context, with feedback from people who weren’t friends or family. My idea was that at the end of the summer I would decide to either commit to working professionally as a studio potter, or give up the fantasy and acknowledge clay as my hobby but not my profession. It was a great summer and I returned to Los Angeles and set up a proper studio, outside of home, got a business license and went to work as a studio potter. I gave myself one year to see if I could make a living at it. That was fall 2002, so it’s been 15 years and in many ways I feel like I’m still just getting started.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

I’m interested in how you see the relationships between the seemingly unrelated disciplines of architecture, clothing design and production and ceramics.

Ceramics, clothing and architecture are all “functional arts” or at least can be. They are all made for and in many ways dependent upon the human body. They are all usually seen as “design” more than “art”. I moved from the hardest and most complicated (architecture) in terms of the amount of people and money needed to realize your work. Making clothing is very similar to making a building in terms of the process, but much faster and cheaper and less dangerous and less regulated. Ceramics I can and do make entirely alone. I have as much control over the process and results as I want. It is an amazing thing to come to work alone and be able to make what I want, when I want. This, in a way, is one of the reasons that I call myself an artist rather than a designer. I come to my studio and make what I want. I don’t have clients to service or problems to design solutions for. It’s not a service business that I am in. Anyway, you get my point I’m sure.

From 2008 to 2013 you worked as a studio director and production potter at Heath Ceramics, a tableware producer founded in the 1940’s with a distinctive Californian modernist aesthetic. What can you tell us about your time there ?

My time at Heath was great. I learned so many things, some about making ceramics and issues of production, some about design, some about running a growing business with a rapidly increasing number of employees and the associated complexities, and some about myself and what I wanted to be doing with my work and my life. It allowed me to work commercially and so not have to worry about money so much, while still giving me the freedom to both develop their homeware ranges with my aesthetic input while also producing more experimental work of my own.

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

When I first encountered your work the forms you were making were controlled and symmetrical and served as canvases for extreme textural glazes. Since then your work has become monumental, less controlled, more chaotic. How has your approach changed since you first started to pursue ceramics professionally ?

I think that I have been following a path without preconceptions of what I wanted my work to look like or be like. The evolution of the approach and the results have been very organic. The one consistent is the potter’s wheel. I love working on the wheel, that’s the foundation of my studio and, in a way, my life. The work has evolved from very clean and tight, reminiscent of modern Scandinavian ceramics, and into a much looser and freer interpretation of those same basic geometries, which are dictated, or at least implied, by the forces of the spinning wheel, circles, spheres, eggs.

I can say that there really isn’t a thought process per se behind the evolution. It is more of a physical evolution. There is a lot of improvisation on the wheel. I think as I’ve aged and become more confident as an artist, things have very naturally loosened up. In the early days I would on occasion think that I was too tight and needed to loosen up. I would intentionally try to make looser work and it always felt horrible, contrived and unnatural, and the results didn’t feel like my work. I felt that they were terrible to look at and touch.

You have developed your own glazes over many years. Can you explain how you do this ?

I am a total caveman when it comes to chemistry. I put stuff together and burn it and see what happens. I’ll find materials where I am working and use them to leave marks on the work. Usually I start by thinking about just a colour or group of colours that I want to use and then start making things and see where it goes. I use glaze recipe books, the internet, and sometimes commercially available glazes as a starting point, and then start altering them through experimenting. Also I multi-fire everything, often many times, to build up layers or to try to correct something. It’s all a bit of a mess honestly, and I can’t really repeat anything, which I like.

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

Can you tell us about your Kimbell Art Museum project in 2012, which brought you back into the orbit of some of your architectural heroes ?

This was a commission to create a body of work celebrating the 40th anniversary of the opening of the Kimbell in 1972. It is one of architect, Louis Kahn’s, finest buildings. In 2010 construction began on a new Renzo Piano designed building, while behind the original Kahn building is The Fort Worth Modern Art Museum, designed by Tadao Ando. Both architects were much influenced by Kahn.

For me as an architecture student, and then a young architect, each of these three architects were very significant, and they continue to have a bearing on my practice as a potter. So to be given this opportunity to engage with the three of them was exhilarating and terrifying. I made three large pots using only materials harvested from the site, which included items gleaned from the partial demolition of the original Kahn building, rust shed from a Richard Serra sculpture and water from the pond at the Ando building.

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

What attracted you to the Grafted project that you collaborated on with Japanese botanist Kohei Oda ?

This project was suggested and orchestrated by our mutual friend Tamotsu Yagi, who is a brilliant designer and art director. He also designed the book of the project as well as my Rizzoli book of a few years before the Grafted project.

Kohei creates ‘mutant’ cactus plants by grafting different species together. Tamotsu thought that I would be a good person to create pots for some of these plants and set us up on what was essentially an international blind date. I was reluctant to do pots for plants as I felt that I had moved past that part of my life and practice, but his work is so special and powerful that I couldn’t say no to Tamotsu. We did a few test pieces where I sent him a few pots and he sent me a few plants and the results were encouraging and exciting so we decided to do the two part show, one in Venice, California and one in Kyoto. We made a total of 100 pieces together over the course of a year. It was a pretty special project.

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

It is self-evident to say that the forms and surfaces of your pieces are organic in quality. What are your inspirations and intentions with these forms ? Your recent show at Cherry & Martin in L.A. was titled Ghosts. Can you explain why ?

In a way I prefer for the work to stand on its own without explanations of influences, intentions. I will tell you that I look a lot at painting, anything from Cy Twombly to Monet to Rothko to Philip Guston. I look a lot at architecture. And dance. But in the end none of that really matters, because I’m making pots and sculptures that must exist on their own in the world.

The title Ghosts (and, at my upcoming show at Pierre Marie Giraud, Fantômes) simply suggests the histories and lives that are inherent in the pieces. Living organisms in the clays and glazes, my hands and actions on the clay, gestures frozen. Lives stopped, but that also live on.

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Landscapes, both urban and rural, are present in your work, and there appears to be a strong Japanese influence. What can you tell us about these ?

Yes there is a lot of this stuff in the work, and all mostly unconscious or not specifically intentional, beyond using materials harvested from my surroundings, both urban and rural. I like the idea of scars and marks coming from the place where I’m working. It’s abstract and people don’t need to know and usually don’t, but to me it feels like the place is in the work and the work is of the place and somehow it resonates and means something, even if it is unspoken and invisible.

Japan is deep in my heart and DNA. When I was in architecture school I was (and still am) a huge fan of Tadao Ando and my first trip to Japan in 1989 was specifically to look at Ando buildings. I’ve been going back there my entire adult life and have so many influences from there inside me that it’s hard to tell where it starts and ends.

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Fantômes is at Pierre Marie Giraud from March 8 – April 7 2018

Interview and all other photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 February 2018

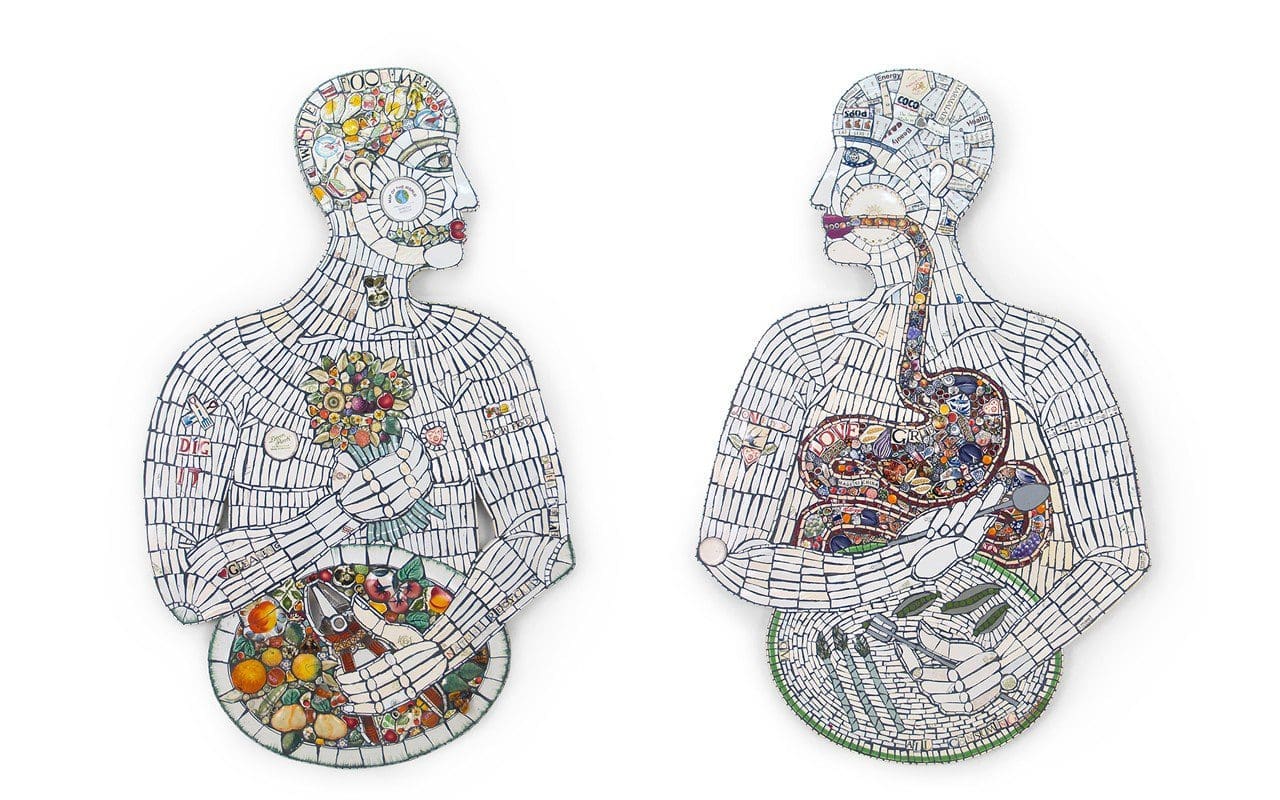

Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.