ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

In 2014 I was appointed as Garden Advisor to Sissinghurst, which was then under the careful guiding hand of Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith. The role involved an annual walk round the gardens with Troy, acting as a sounding board for his plans to relax the garden and to steer it gently towards its original vision. Over time, and without the owners at the helm, the gardens had been managed to provide their very best for the swell of visitor numbers. I agreed they no longer resembled the gardens of Vita’s writings or her freedom of spirit.

Troy had spent hours immersing himself in Vita’s imaginings, hopes and plans for the gardens, and had written a manifesto that called for a return to a more relaxed and wild, romantic vision closer to Vita and her husband, Harold Nicolson’s, original intentions.

Every time I visited we skirted around Delos, a garden that had originally been built in response to a visit that Harold and Vita had made in 1935 to the ruins of the Greek island of this name in the Cyclades. The garden had been lost, planted in the wrong place, facing north on heavy Wealden clay. It was a place that had come to be more suited to the site and was now part woodland, part lawn with rose beds lining the boundary. The very name felt like an anomaly.

It was in 2018 that Troy asked me if I would work with him and his team to re-imagine the garden. It was daunting making changes to a garden as universally loved as Sissinghurst, but we set to and looked carefully into the history to understand why Harold and Vita had felt compelled to bring something of the ruined island back to Sissinghurst. Troy had sent two members of his team on a field trip to study the vegetation and record the mood of Delos. The time that I too have spent in Greece provided rich inspiration with regard to the planting. We worked carefully with the National Trust historians to test our ideas as they emerged and spent the best part of a year planning. Visiting a local quarry with Nigel Froggatt, the masterful craftsman who built the garden and taking time to mock up the walls so that they felt authentically of the island.

The design made some bold moves that perhaps Harold and Vita did not have the know-how to make at the time. We made light by editing the existing trees back to a Quercus coccifera from the original planting and harvested the sun by battering a number of terraced walls back into the sun to face south. The original axis was reworked to feel like the stepped ruins we had seen in photographs of the garden taken not long after it was made. The terraces that moved away from it became rougher to invoke the hillsides into which the ruins had fallen. We made the old well the centre of the garden, a communal meeting place as it would be in a Greek village and made a seating place amongst columns where Vita had imagined that the blue of the distance could conjure the sea.

I went on my own research trip to workshop the palette of Greek natives with Olivier Filippi at his nursery in the south of France. His knowledge and plant selection is superlative. Some plants were untested in this country, others entirely familiar. On returning to the UK I worked up the planting areas. Goat paths where the aromatic plants would brush your legs and shade-loving drought lovers that would sit happily in the shadow of Judas trees. A mature pomegranate forms a gateway from the White Garden. A fig and the rough twist of cork oaks will, in time, provide height and volume. Aromatic evergreens are already hugging the terraces and perfuming the garden on a hot day and the ephemerals, the annuals that make a Greek spring the spectacle it is, are already beginning to find their niches to make the garden feel lived-in.

Last week, over a year since my last visit for the final planting day in the week before the first lockdown, I returned for the official opening. The garden felt settled and possibly better for the enforced pause of the lockdown and Saffron Prentis, who has been in charge of the garden, has tended it beautifully. The volunteers who man the garden every day have been there to communicate the story behind it and its reimagining.

In 1953, Vita wrote of Delos, ‘This has not been a success so far, but perhaps someday it will come right.’ I know that the changes have not been liked by all who have seen the garden in the flesh or online, but when I returned last week with the planting already looking established after just 18 months, it was possible to see that Vita and Harold’s vision of a Grecian isle transported to the Kentish Weald is once again alive at Sissinghurst and coming right.

_._._._._._._._._._._._._._

When we first started work, Adam Nicolson, Vita and Harold’s grandson, was immensely helpful in facilitating our understanding of the deep-seated cultural motivations of both Harold and Vita to create this garden. At the opening last week he very kindly offered to write a piece giving his perspective on Delos, then and now and I am delighted to share it with you here.

Dan Pearson, Hillside, 8 July 2021

The official opening of the new Delos at Sissinghurst last week is only a beginning. The new cypresses will soon stretch and thicken, the new figs will sprawl and lounge across their neighbouring boulders and walls and the individual plants of Dianthus cruentus will spread and merge into rivers of deep pink, bee-happy colour. A long future awaits this garden, as something to take its place alongside the Purple Border and the White Garden as the brightest of stars in the Sissinghurst constellation.

It has been a long time coming. Throughout my childhood at Sissinghurst, we always knew that in the 1930s Vita and Harold had wanted to make a Greek garden in this most unpromising of clay-wet, north-facing and very very Kentish corners. They attempted it, assembling some of the Elizabethan stones they found lying there into stepped platforms that vaguely recalled temple foundations in the drought of the Aegean. But the soil was wrong, the site was wrong and over the years a series of efforts were made to redeem it. My father removed all those stones to make the foundations of his gazebo; a very American grove of birch-like magnolias was planted to preside over a carpet of scillas and chionodoxias through which a few peonies poked their heads; new brick paths were laid. Delos had essentially been lost.

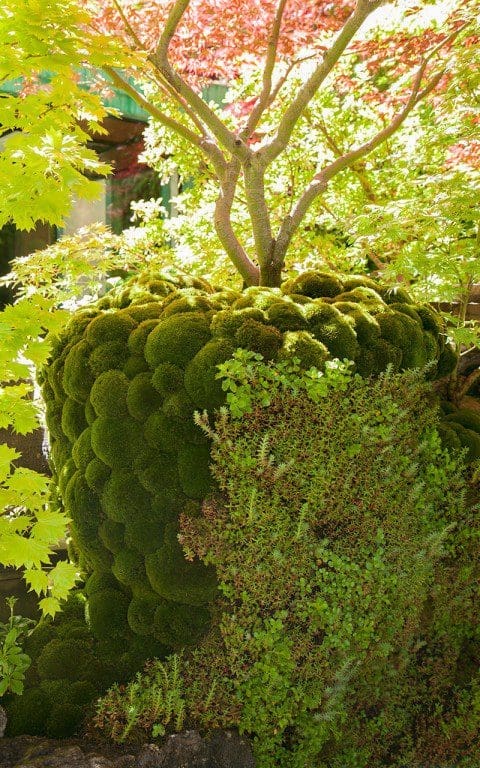

It has now been found and in the richest possible way: the silhouette of a flowery garrigue billows up in front of big country rocks; rubble-terrace walls firm up into what might be the foundations of buildings along the central street of this forgotten city; the half columns of an abandoned temple stand on the slope above.

It is pure theatre, as it was always intended to be, entirely dependent on a big, hidden drainage system and an especially free-running soil, with plenty of grit and crushed brick to make the Mediterranean plants feel at home. Clay is nowhere to be seen.

There is one element that reaches further back into history than the dreams of the 1930s: three cylindrical Greek marble altars, originally carved in the 3rd or 4th century BC, decorated around their waists with swags of grape, pomegranate and myrtle suspended between garlanded bull-heads — boukrania—which now stand at key intervals along the central street of the garden. Perhaps almost unnoticed among the blaze of life and colour around them, these altars remain the core of the garden and its meaning. They are the reason it is called Delos, as they came originally from that famous island in the Cyclades, sacred to Apollo, and represent an element of the story that was undoubtedly close to Harold Nicolson’s heart.

His mother’s grandfather was Commodore William Gawen Rowan Hamilton, a naval commander in the first years of the nineteenth century, a heroic and romantic figure and passionate Philhellene, who spent the years from 1820 onwards in the eastern Mediterranean, winning the title of ‘Liberator of Greece’ by protecting the Greek rebels against the Turks and spending much of his private fortune in their cause. There is still a street in Athens named after him in gratitude.

From time to time during his cruises attacking pirates and fending off the Turk, he would land on an island or a piece of the Turkish-occupied mainland and quietly liberate an antiquity or two, sending them back to his liberal father-in-law in Ireland, Major-General Sir George Cockburn, a flamboyant antiquary who had made a collection of Greek statuary at Shanganagh, his castle outside Dublin.

These Delian altars arrived there in the late 1820s, dripping with Greek-loving, liberty-loving significance, and when in 1832 the British government promised in the Great Reform Bill to democratise the corrupt state of British politics, Sir George erected them in a column to Liberty outside his front door. They stood there for six long years, during which the government entirely failed to reform the basis of British politics, and in rage and frustration, Cockburn had carved on the base of the monument the grand reproach: ALAS, TO THIS DATE A HUMBUG.

In 1936, when the contents of Shanganagh were sold up, Harold Nicolson bought the elements of his great-great-grandfather’s column and had them transported to Sissinghurst. The HUMBUG base and one altar is still in the orchard; the three others are in Dan’s new Delos, still in my mind radiating everything which that long, Rowan-Hamilton-Nicolson tradition valued most: a love of liberty; an internationalist, pan-European vision; a cosmopolitan grasp of and engagement with world culture; and a treasuring of those dry, beautiful, ruin-scattered landscapes sacred to Apollo which this Kentish garden now recalls.

Adam Nicolson, Perch Hill, 3 July 2021

Photographs | Eva Nemeth

Published 10 July 2021

We have been visiting the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido this last week. It was my annual visit to meet with Midori Shintani, the head gardener, to gauge the past year’s developments and help move the garden gently forward. Gardens are never static and the elemental nature of the surrounding forest and the backdrop of the Hidaka Mountains has a strong influence here. In 2016 a typhoon hit the forest, swelling the braided streams and charging them with boulders that swept away the footbridges. Miraculously the waters parted around the garden, but we have only just recovered from the influence. This past winter the eiderdown of snow was not as deep enough in parts to insulate all of the plants effectively and so the minus twenty degree winter has taken its toll in some areas.

Such are the challenges faced by Midori and her assistant head gardener, Shintaro Sasagawa, and when I arrived they were already well advanced on replanting the areas that had been worst affected. This year – for with contrary mountain weather every year is different – we found the garden in a cool, damp week. The cloud hung heavy to shroud the mountains and the Hokkaido drizzle bowed the perennials in the garden to the ground. The northern climate here compresses the summer so that it rushes fast in the growing season and, though the garden was pausing between the first flush of early summer and the coming wave of high summer colour, we saw significant change in the five days that we were there. Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’ starting to open its flame-red tapers and Cephalaria gigantea reaching ever taller over a river of Achillea ‘Coronation Gold’.

Huw accompanied me this year because we were also meeting to discuss the book I am currently writing to be published by Anna Mumford of Filbert Press next autumn. The richness of the Tokachi Millennium Forest and the way that it is being tended has a growing following and so the book feels timely. Midori is contributing to the book and one of the most important themes she will write about is the ancient Japanese tradition of satoyama – the practice of living in close harmony with and showing reverence for the land. A renewal of this approach, where the people make the place and the place makes the people, has been a central component in the genesis of the gardens.

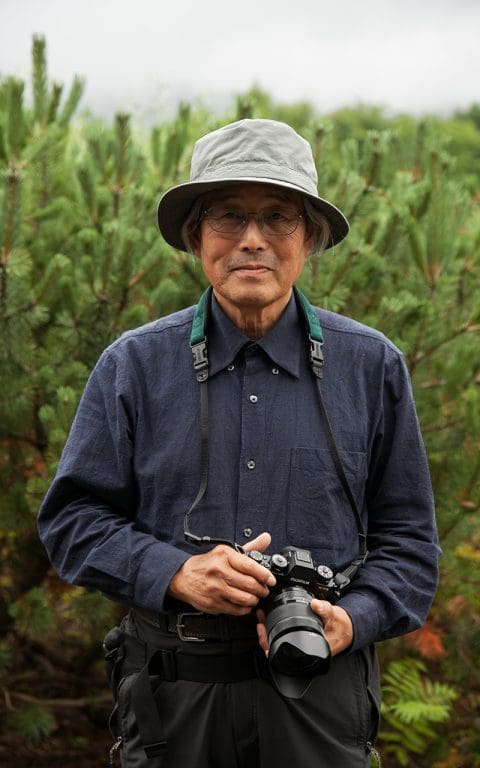

We met with Kiichi Noro, a highly respected landscape photographer in Japan, and a man of great humility who has been recording the forest and gardens for the last 5 years. He has delivered around 40,000 images, which need to be distilled to ensure that we capture the gardens and all the nuance of the forest influence throughout a working year. Huw has been working on the picture selection and look of the book with Julie Weiss who is designing it, and who also joined us in Hokkaido. Julie used to be an art director at Vanity Fair magazine before changing direction three years ago, since when she has immersed herself in the world of horticulture, working as a trainee gardener at Great Dixter and travelling to see and learn as much as she can.

We are also doing what we can to provide educational opportunities. Midori and I led a Garden Academy this week, spending an afternoon talking 40 attendees – many of whom had travelled from other cities in Japan, and one very keen group from Korea – through the principles of the Meadow Garden and how its sits alongside the gently tended forest that inspired the planting. Midori has also taken gardeners from Great Dixter on an exchange basis as well as student gardeners from around the world who have taken it upon themselves to write to her. This year there are three volunteer gardeners from overseas working in the garden to gain a deeper experience and understanding of Japanese gardening practice and culture in general. Two young English designers, Charlie Hawkes and Alice Fane, who are staying this year from snow melt to snow fall and Elizabeth Kuhn, a horticulturist and nurserywoman from America with a particular interest in the native flora.

The woodland is the ultimate inspiration for the way that everything is done here and I return to it constantly to provide me with focus. In the week we were there we watched it moving through its final peak before dimming now that the canopy of magnolia and oak has closed over. Stands of Cardiocrinum cordatum var. glehnni stood tall and luminous to scent the pathways. The glowing purple spires of Veronicastrum sibiricum var. yezoense stood sentry at the forest edge. The vestiges of Trillium and earlier flowering Anemone and Glaucidium are already in the shadow of the Angelica ursina which were pushing up in a last great bolt of energy to flower. Most had not yet reached their full height, but those that had broken into flower stood twelve feet high with the parasols of Petasites japonicus ssp. giganteus at their feet.

Walking through the forest was as spellbinding as ever and you cannot help but feel charged by the experience of being there. Now all we have to do is try to capture that on the page so that the forest reaches beyond its boundaries, as it should.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 July 2019

In 2015 I was approached to work as the landscape designer for a new extension at the Garden Museum. The renovations were extensive and it was the second phase of the project for Dow Jones Architects. The first, in 2008, had been to create a series of freestanding structures that moved lightly through the heritage building. This final push would see a new extension reaching out into the garden to create spaces for education, events and a new cafeteria.

The plan for the extension sailed over the footprint of the old knot garden which previously occupied the site, to enclose a new courtyard where the tombs of the Tradescants (father and son) and Captain Bligh take centre stage. The achievements of these three men provided a strong brief for the garden, which reflects their pioneering spirit as adventurers, plant hunters and educators. The Tradescants, once residents of Lambeth, had conceived their garden as a reflection of Eden and so the new cloister was also intended to be a place of sanctuary, where the seasons are brought into close perspective in the centre of the city and the planting is the focus of learning.

We pondered for some time over the removal of the well-loved knot garden, which Lady Salisbury had designed for the museum in 1980, three years after it first opened as the Museum of Garden History. Initially we worked up a series of iterations to abstract the knot garden to see if its memory could be glimpsed in the new design, but the architecture required a more confident forward-looking approach to move the garden, with the museum, into a clearly defined, bold new chapter. However, drawing from the existing sense of place was also important, so the ledger stones from the old graveyard and the bricks from the knot garden were integrated into the path that creates a frame from which to look into the planting. In the corner, where the tombs were close to the path, we extended its reach to allow closer observation of the detailed carvings and inscriptions. An old mulberry and an arbutus were retained in the new design, while an old fig and medlar were carefully moved to beds at the other end of the church. The street-side plane trees, which are protected and provide the museum with its leafy, woodland feeling, were able to have the building so close thanks to a piling system which floats the extension carefully over their root plates.

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

The street-side planting beneath the London Planes with Euonymus planipes on the left

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Aralia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’

Viewed from four sides (through glass on three and an open, covered walkway on the fourth) the courtyard garden – called the Sackler Garden after a generous donation from the Sackler Foundation – would become a point of focus within the cloistered enclosure. The new glazed walls would also enhance the London microclimate and help buffer the garden from the wind that uses the River Thames as a corridor in this location. With the exploits of the Tradescants as inspiration, it was a small step to imagine this courtyard as a giant Wardian case – an aquarium-like structure invented in the 19th century to transport exotic and delicate new plant discoveries long distances by sea in a protected environment. The glassy cloister, our metaphorical Wardian case, allowed us to present a garden of curiosities and treasures.

Though an oasis, as a space it is far from hermetic. The planting continues on the street side of the café beneath the planes with a shady carpet of hardy evergreens and woodlanders including Hakonechloa macra and Epimedium sulphureum. A specimen Euonymus planipes was planted to frame the cafeteria door and emerging perennials such as Danae racemosa, Aralia cordata and white persicaria and wind anemone provide the planting with seasonal flux and help make the connection to the green world within. From the street the transparent walls of the café allow an intriguing glimpse of the jungly courtyard planting.

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

Looking into the cafe across the woodland planting from the street

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

The courtyard garden can be seen from the street through the glass walls of the cafe

As the courtyard is a deliberately acute focus, it was important that it be a dynamic space that works on every day of the year. When choosing the plants, I felt it was important to continue the spirit of discovery exemplified by the Tradescants and for the plants to tell a story of horticultural history. I also wanted the composition and plant choices to capture the magic of an 18th century botanical engraving and key into the gothic mood of the churchyard and its tombstones.

Modern day plant hunters, such as Sue and Bleddyn Wynn-Jones of Crûg Farm Plants helped provide us with some of the curiosities. Fatsia polycarpa, a rarely seen castor oil plant with deeply divided, elegant fingered foliage, and a Schefflera from Taiwan, complete with precise location notes to bring their provenance to life. Nick Macer of Pan-Global Plants also provided us with some of his wild collections. A giant foliage Dahlia from a trip to Mexico, and flowering gingers for points of exotic interest. I wanted the planting to feel eclectic – a collection – and the exotic edge was important to conjure the feeling of awe and wonder that must be felt by all plant hunters. Canna x ehmannii and Tetrapanax papyrifer have done this at scale and made an immediate impact, whilst more demure curiosities such as Disporum cantoniense ‘Night Heron’ and Epimedium washunense ‘Caramel’ provide the detail once you start to look deeper.

It was of prime importance to the museum that the garden provided a centre of horticultural excellence and the planting has been layered to create an ecosystem where each component in the composition provides a microclimate for its neighbours. The layering has also allowed the play of form and texture to work in combination and, importantly, for the sequencing over the course of the year to reveal change so that the garden is different each time that you visit.

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The Sackler Garden at the centre of the new extension. William Bligh’s tomb is in the centre, that of the Tradescants can just be seen on the far right

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

The layered planting includes, from left, Canna x ehemannii, Dryopteris erythrosora and Equisetum hyemale. Behind is a seed-collected species Dahlia from Pan-Global Plants. The groundcover is Geranium maccrorhizum ‘White Ness’, a 20th century discovery.

Canna x ehemannii

Canna x ehemannii

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

Nandina domestica and Astelia nervosa

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

On the left Tetrapanax papyrifer with Astelia nervosa beneath and Rubus lineatus to the right. Behind are a Schefflera species from Crûg Farm Plants with Nandina domestica

Nandina domestica has been planted around the tombstones to reflect its auspicious use as a welcome plant in China, but look carefully and in amongst its stems, like the layers in a rainforest, there is a mingling. Pewter Astelias from the Chatham Islands, delicate maidenhair ferns, the Australian violet, Viola hederacea, and black-leaved Ophiopogon nigrescens in their shadows. I wanted the garden to have plants that had a recognisable use amongst the curiosities too. Wild strawberries, that once would have grown locally in Lambeth, alongside Meyer lemons and passionfruit to remind us how we too often take the provenance of our food for granted.

Having just completed its second summer, the garden is settling in and taking shape in the careful hand of Matt Collins, the museum’s head gardener, a horticultural trainee and a number of volunteers. A planting of deliberate complexity needs a well-informed eye to keep it looking good and it is a delight to return and to see it evolving. The potentially invasive Equisetum hyemale is kept in check and in its place to score its vivid green vertical and exotic climbers scale the cloister pillars.

It has been a privilege to be part of this exciting new chapter and now also to help in developing the next. On Thursday this week the Garden Museum announced Lambeth Green, a new initiative to turn St. Mary’s Gardens alongside the Museum into a community hub, a village green for Lambeth, and also to reach its green tentacles further out into the streets to reconnect to the river and nearby Old Paradise Gardens. With the new incarnation of the Museum as a catalyst, it is now easy to see these exciting possibilities being realised.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan Published 10 November 2018

I have recently returned from the opening of one of my biggest projects to date and feel the need to tell the story, as it is remarkable for its scale and farsightedness. Mr. Ma, our client and the visionary behind the forty-five acre development, started the journey over fifteen years ago. A dam was about to be built near his hometown in Jiangxi province south-west of Shanghai, and with its construction came the loss of the valley’s ancient camphor trees and Ming and Qing dynasty settlements of merchants’ houses. By the time I came into the story, and indeed it was the reason that I did, Mr. Ma had moved over ten thousand camphor trees to their new home in Shanghai.

Their journey was an extraordinary one. Some are believed to be almost two thousand years old and were so big that they had to be transported the 600 kilometres on army tanks. Bridges had to be made to get them across rivers, and tunnels excavated so that the cargo could pass. The trees were planted in a nursery on the outskirts of Shanghai, very close to a site which Mr. Ma had secured for a new development. Here a series of old warehouses were also repurposed for storage of the merchants’ houses which had been dismantled brick by brick and painstakingly repaired from the damage they had sustained during the Cultural Revolution.

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

Mr. Ma with some of the rescued and replanted camphor trees

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A warehouse containing some of the dismantled Ming and Qing dynasty merchant’s houses

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

A detail of the stone carving on one of the antique villas

I was introduced to Mr. Ma in 2012 by his friend and collaborator Han Feng, who had been tasked with helping to find a landscape designer to design the grounds. Han Feng and I had met at the Design Indaba in Cape Town earlier that year, where we had both been invited to speak and we met in London to talk about the project. I was inspired by the story of the rescued camphors and the idea of making them a new home, so we agreed to meet Mr. Ma when I was next in Japan at the Millennium Forest so that he could see my work there.

By this point Aman Resorts were collaborating with Mr. Ma to make a hotel and associated grounds and Kerry Hill Architects had worked up a masterplan for the site. Once I was on board we were tasked with detailing the whole site from the hotel to the streetscapes and a series of garden blueprints that would be used to furnish the gardens of 44 private villas; 26 antique merchant’s houses and 18 contemporary interpretations of them.

Mr. Ma was busily working away in the background with the government to secure a site of double the size that would become the backdrop to the development and allow the green lung of the camphor forest to reach out and take on this new ground. We were also tasked with designing the masterplan for the park, repurposing one of the agricultural canals to form a dividing lake and masterminding a wetland of considerable scale that would allow us to recycle and purify all the water that would be needed for the water features on the site. It was an extraordinary opportunity to create a public park that would also act as an environment to include wetland walks, meadows and a considerable acreage of woodland. A green heart for a new city that was quickly sweeping up and around the site, as the agricultural land was repurposed for the urban sprawl.

The site masterplan with Amanyangyun in the north and east and the forest park to the south west

Once it was complete we passed the park masterplan on to a local firm of landscape architects and concentrated our energies on the Amanyangyun site. However, it is gratifying now to know that the first phase – the lake, the wetland and the woodland that links the two sites – is already in place. In China things happen at an alarming pace and at a scale that we are unaccustomed to here, so in many ways it was good to pull back at this stage after securing the big ideas and concentrate on the detail of Mr. Ma’s site.

It took two years of careful collaboration with the architects, who were a delight to work with, clear in their thinking and open to the contrast of an informal overlay on the rigorous grid that defined their masterplan. My own journey, and that of the team that works with me in the studio, was put on a very steep learning curve. We had to learn fast about the very different cultures and way of doing things and we couldn’t have done that without the trust and thoughtfulness of our client who had put a team in place that helped to translate our ideas.

We were taken to see traditional Chinese gardens to understand their ethos, aesthetics and cultural importance. They were completely new to me, the precursor to the Japanese gardens which I have come to know well from my time spent there, but entirely different in their aesthetic. I was keen not to emulate the Chinese garden at the villas on the site, but it was important to understand the culture and how we could create something naturalistic that would sit comfortably in Shanghai and not feel out of place.

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

One of the camphor-lined streets during construction in 2016

The same view this year

The same view this year

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

The king camphor tree at the heart of the construction site has a red ribbon tied round it

A different view of the same area after completion

A different view of the same area after completion

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

Mr. Ma and the king camphor tree at the opening ceremony in April

We soon found that, despite the vast range of Chinese plants that we grow and depend upon in the west, our choices on site were very limited. The Chinese garden depends upon a tiny palette compared to a western garden and thus the nursery trade there is very limited. Bamboos, from ground covering forms to timber bamboos, were not in short supply, neither were Nandina and Osmanthus, but our tree palette was narrow, with only two magnolias to choose from, M. grandiflora and the beautiful M. denudata. We had flowering Malus and plums, camellias and a number of auspicious fruits that we used close to the buildings. And there was no shortage of Chimonanthus so the building blocks were enough. It was what we did with them that made the difference.

Modern landscape design in China sees the groundcover layer packed densely with blocks of low level shrubs, such as azalea and Fatsia, but I wanted breathing space between a multi-stemmed layer of flowering trees that would sit under the canopy of the camphors and keep the space at human level feeling airy and light. We designed a number of groundcover mixes that mingled the staples together informally. Ophiopogon and Liatris sweeping through in a gently shifting constant with runs of Aspidistra in the deepest shade, which was replaced by the likes of Iris sibirica and Chasmanthium latifolium out in the glades, where we had made room for the light to break the overarching canopy.

Overview of the villa complex

Overview of the villa complex

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance garden of an antique villa the first spring after planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Entrance walkway iris planting

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

Rear private pool garden of an antique villa

We used a palette of Chinese natives and local wetland species to encourage wildlife, but pumped up the volume amongst the restful sweeps of green with lotus ponds that sat close to the buildings, coloured Nymphaea in water bowls on the terraces and highly scented Gardenias by doorways. The climate, though temperate, is just that bit warmer than London so we were able to include bananas in sheltered corners and Trachycarpus for the grandeur of architectural foliage.

After my initial dismay at the apparent limitations of choice, our palette soon felt big enough to do something interesting, but I did choose to import Hydrangea serrata from Japan, as we only had access to hortensia and H. quercifolia. By including the H. serrata we were able to ring the changes and make the development singular. Pink, white and ‘Macrobotrys’ Wisteria floribunda were also imported as we only had access to Wisteria sinensis, which is the shorter-flowered of the two species. These additions to the staples and the commitment to breathing spaces in the planting soon made the difference.

The main riverside entrance

The main riverside entrance

The hotel entrance

The hotel entrance

We honoured the Chinese traditions with an auspicious fruit tree by every door and trees and shrubs that represented welcome or well-being and were well known for this layer of storytelling in the landscape. Our plans were all vetted by a feng shui master before anything was built – and we had to make some changes, but most of the moves in geomancy are based on good common sense and the changes were few. I suspect we were lucky.

There are numerous tales to tell about how we got to the point that the hotel and the grounds of the first villas were finally opened this spring, but they finally are and behind the scenes work continues to complete the remaining parts of the site. Though the planting has been in a year at most, it is already beginning to pull the buildings together. You look up to see the camphor trees regenerating, the King tree in the main courtyard already assuming presence. It will be a time before their branches reach to touch and cast shade, but it is good to have been part of helping them to do so.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Dan Pearson and Sean Zhu

Published 2 June 2018

A month ago I was in Japan, on my annual visit to the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been working at the forest for sixteen or seventeen years now and the yearly journey is always rewarding. It is a place with a big vision, where half the side of a mountain and the forested foothills are the domain. It has the feeling of the north, with air that slips over the mountains from Russia not so far away. Bears really do live in the woods and the landscape freezes to minus twenty-five, under a blanket of pristine white from early November through to the end of April.

The owner, Mitsugishe Hyashi, bought the land with the ambition of offsetting the carbon footprint of his newspaper business, but the park represents far more than this. He also set out for it to be sustainable for the next thousand years and it is a privilege to have been part of this vision and to be a small part in shaping the park’s direction.

The gardens and the managed forests are a big part of helping to communicate the big idea to visitors. The gently managed places, which take the rough edges off the wilderness, are part of making people feel comfortable in the areas that are accessible. Takano Landscape Planning, which put together the original masterplan, knew that the people and their comfort in the environment were important and, when I was asked to be part of the project in 2000, it was to help with creating a series of spaces that would provide the landscape with a focus for the public.

The Earth Garden

The Earth Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Rose Garden

The Rose Garden

In their turn, the gardens we have since created have been key in making a ‘safe’ place and a link with the magnitude of the landscape, to literally ground the visitor in the place. A landform called the the Earth Garden, which reconfigured a clearance field that separated the visitor from the mountains, was the first of the projects to come to fruition. A series of grassy waves, echoing the undulations of the mountains beyond, now provides the visitors with a ‘way into’ the landscape. By exploring the earthworks they soon find themselves at the base of the mountains or at the edge of a mountain stream or a trail into the woods. The landforms extend to wrap another five hectares of cultivated garden, and area named the Meadow Garden, which was planted to celebrate the official opening ten years ago. Beyond that there is the Farm Garden where people can see a modestly-sized productive space with fruit, vegetables and cutting flowers and eat food grown there at the cafeteria. A goat farm producing cheese is the backdrop to this space, while most recently we have developed a Rose Garden of hybrid and species roses suitable for a northern climate and an orchard to test growing apples and other top fruit this far north.

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest, where Fumiaki Takano had already made a start when I was brought on board, eases visitors in with soft bark paths and decked walkways that take them back and forth across the rush of mountain water that switches between the trees. The low native bamboo Sasa palmata, which took over the forest after its balance was disturbed when all of the oak was logged at the turn of the last century, has been carefully managed to encourage a more diverse regeneration of the forest floor. Repeated cutting in the autumn, coupled with the short summers that curtail its regrowth and stranglehold, has been diminished enough for the window of opportunity to be given back to other plants in the native seedbank. Wave upon wave of indigenous plants now greet the visitors. Anemone, Caltha palustris var. nipponica and Lysichiton camtschatcense seize the window after snow melt and, as oak woodland comes to life, the race continues with Trillium, scented-leaved and candelabra primulas and arisaema. By the time I arrived in late July, the woodland was tall with giant-leaved meadowsweet, cardiocrinum and lofty Angelica ursina.

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Filipendula camtschatica

Filipendula camtschatica

The Meadow Garden (main image), my primary focus with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani, was inspired by the woodland and the way the plants have found their niche and live together in successive layers of companionship. Sitting on the fringes of the wood where dappled light meets sunshine, it is divided into two main parts by a meandering wooden walkway. The lower areas emulate the edge of woodland habitats, while above the path the planting basks in full sunshine. The planting is further divided by swathes of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, which separate the different colour fields, so that the yellows are held back as a surprise. The movement of the mountain winds is caught in their plumage to animate the garden.

The plantings integrate Japanese natives with plants from other regions of the world that have similar climates. North America and parts of northern Europe provide the ‘exotic’ layer in the garden and their inclusion draws attention to the Japanese natives that are mingled amongst them. Plants such as the Houttuynia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Aralia cordata. Everyday plants in Japan that are given a new focus. In terms of my own gardening process, these plants were the exotics and it has been such a fascinating process to reverse my experience of the exotic/native balance. Native Lilium auratum, the Golden-Rayed Lily of Japan, and the giant meadowsweet, Filipendula camtschatica, are teamed with Phlox paniculata ‘David’. Sanguisorba hakusanensis, the extraordinary pink, tasselled burnet is in company with Valeriana officinalis and Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’.

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

The original planting plans were designed as a number of individual mixes, planted in drifts to allow the planting to flow across the site. Each mix contained a small number of species, usually five to seven, that were planted completely randomly. The percentages in the mix were critical, with a small number of emergent plants such as the Cephalaria gigantea to rise above larger percentages of individuals that would knit and mingle at lower and mid-level. Now that I look back it was a brave move, because it was entirely dependent upon the head gardener to steer and monitor.

Midori has been more than I could have hoped for in an ally on the ground and our yearly critique and analysis of the plantings is a high level conversation that looks both at the big picture and also at the detail. Of course, there have been adjustments to refine each mix as they change yearly with plant lifespans, climate and vigour, which drive our response. But we have also needed to make changes to keep the garden moving forward, introducing new plants and swapping or reducing the numbers of those which have become dominant. For instance, we have found plants that will happily coexist in a demanding matrix of twenty five companions in the wild, can take their opportunity to dominate when given just a handful of company.

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Last year, to challenge the thousand year brief of sustainability, a tornado swept across the island. It hit last summer, just before I visited and I arrived to see the carnage. The mountain water had swelled the streams that braid the site to rip and tear and deposit a silver sand from afar and boulders that are now new features. Miraculously the waters divided to either side of the Meadow Garden, but they swept away all but two of the bridges, which have never been found. We were left feeling very small and of little consequence within the time frame that had been set for the preservation of this place.

The repairs have been slow but sure and in scale with what is possible. New shingle banks have been embraced as the new places and opportunities that they are. Already they are being colonised. It is the gardener’s way to repair and to move on, but we have been humbled nevertheless. Midori walked me through the garden, pointing out ‘weeds’ that have been swept in to the planting that were never there before. And there are anomalies that are hard to get to grips with that point to changes of another scale. Some plants have taken a hit a year later to sulk or fail, and we do not know why, whilst others have seized life with a new vigour as if the charge from the mountain has revitalised them. With ten years under our belts and the knowledge we have gained that is specific to this place, we are adjusting again and moving on. On to a second decade and the certain changes that we will be responding to, to move with it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Kiichi Noro and Syogo Oizumi

Published 16 September 2017

Last Friday I was honoured to speak at the University of Essex in support of The Beth Chatto Education Trust, of which I am a patron. My brief, to talk about the importance of education in horticulture, was an easy one to meet and that much more relevant with the Trust firmly up and running. Julia Boulton, Beth’s granddaughter and Managing Director of the Gardens and Director of the Trust, has made it her mission to utilise the garden as an educational resource and it was with much excitement that we met to celebrate the fact that the garden now has this important new future.

Beth Chatto (centre front) with behind (left to right) Dave Ward, Garden Director, Julia Boulton, Managing Director, Dan Pearson, Karalyn Foord, Education Trust Manager and Åsa Gregers-Warg, Head Gardener

Beth Chatto (centre front) with behind (left to right) Dave Ward, Garden Director, Julia Boulton, Managing Director, Dan Pearson, Karalyn Foord, Education Trust Manager and Åsa Gregers-Warg, Head Gardener

Beth’s work has always been important and the garden is as relevant today as it ever has been. At the forefront of the naturalistic movement in this country, and instrumental in originating the ethos of ‘the right plant in the right place’, Beth’s displays at The Chelsea Flower Show were ground breaking in the 1970’s. I remember their singularity, for no one else at the show was using the plants that she was cultivating or combining them as intelligently; plants that were wild in feeling, always close to the species and grouped according to their habitat needs, not the whim of colour themes or border compositions. Apparently, in the early days, some show judges are said to have dismissed her displays as being nothing more than cultivated weeds, but the message to gardeners was strong, practical and consistent; put a plant where it wants to be and it will thrive. It is barely credible now that this approach should have been seen as unusual, but in the days of annual bedding, hybrid tea roses and prize dahlias Beth’s was a shock doctrine.

And she was far more than simply the nurserywoman who presented her wares at the show. You could also depend upon her not only for her impeccable taste, but also for her ability to educate you through her plantsmanship. For years Unusual Plants was the only place to go to get the plants I wanted to grow and I pored over the evocative descriptions in the catalogue. My borders in my parents’ garden were stocked with her treasures and it was through a love of her plants that I bonded with my first client, Frances Mossman, with whom I created the gardens at Home Farm. We had both fallen under the spell of Beth’s catalogue and I remember very clearly a key conversation about Beth’s description of Crambe maritima. A seaside wilding brought to life and into horticultural focus through words. A world of opportunity that was suddenly possible once you made the connections. When I started travelling to see native plants growing in the Himalayas, Israel and Europe in my ’20’s Beth’s ethos was plainly articulated in every plant community I saw and helped me make the connections between the wild and the cultivated.

Earlier last Friday, before the talk, we took a tour of the gardens with Dave Ward, the Garden Director and long term member of the team. At the Gravel Garden (main image) we stopped to catch up with Beth, who had come out to greet us and marvel at the Romneya. Just two days after celebrating her 94th birthday she had lost none of her fervour for the importance of horticulture and was vocal about how good education and competitive salaries are essential to encourage young people into the profession. It was so good to see her in her environment and I remembered how she had once talked about being in New Zealand with Christopher Lloyd and had dreamed of making this garden after they had come across a dried up river bed.

Repeated Genista aetnensis set the mood, its peppered clouds of gold, luminous against the dark hedges. Nothing looked out of place, with all the plants chosen for their drought resistance and moving about in the gravel as if they had found their way there and their companions quite naturally.

Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’ and Stipa gigantea

Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’ and Stipa gigantea

A repeat of vertical verbascum to arrest the eye; Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, dull white and caught in a gauze of Stipa gigantea, with a smattering of pink Dianthus carthusianorum. Felted Verbascum bombyciferum standing alone and breaking free at the very edges of the planting. Romneya coulteri fluttering close to the path so that you could inspect the boss of golden stamens. A stand of Stipa barbata given their own space and floating like seaweed in the breeze.

The feathered seedheads of Stipa barbata with Verbascum bombyciferum and Romneya coulteri against the hedge

The feathered seedheads of Stipa barbata with Verbascum bombyciferum and Romneya coulteri against the hedge

There were many plants that I am using at home which Beth introduced me to as a child (Eryngium giganteum, Lychnis coronaria, Crambe maritima, Romneya coulteri, Stipa gigantea, Dianthus carthusianorum, Phlomis russelliana) and others that I have come to from other directions, but surely because of Beth’s influence. An acid-yellow mist of Bupleurum falcatum through which the dark orbs of Allium sphaerocephalon were suspended. Buttons of pale yellow Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, hunkered down and throwing off light. Splashes of electric-blue Eryngium x zabelii, metallic and architecturally jagged amongst the softness.

Allium sphaerocephalon, Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, Bupleurum falcatum and Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’

Allium sphaerocephalon, Santolina pinnata subsp. neapolitana, Bupleurum falcatum and Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’

Eryngium x zabelii with Bupleurum falcatum

Eryngium x zabelii with Bupleurum falcatum

We moved from there into the lower sections of the garden where the compositions were driven by green and texture. Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg reminded us of Beth’s love of ikebana and the asymmetric triangle that repeats in her compositions. Watery reflections, plants adapted to their foothold, be it edge of the dry oak woodland or spearing Thalia dealbata amongst scale changing Alisma plantago-aquatica in the shallows of the ponds. Splashes of fiery candelabra primula amongst green umbrellas of Darmera peltata and in a narrowing on the way to the Reservoir Garden, the oversized creamy plates of Sambucus canadensis ‘Maxima’, a plant that I haven’t grown since I was a teenager. On enquiring about its availability (I had the nursery set firmly in my mind as a highlight of the day) Dave tipped me off. “You can get that at Great Dixter.” More connections from my early education. A plant I had all but forgotten about but, all these years later, am just as excited to be revisiting.

The Water Garden

The Water Garden

Alisma plantago-aquatica with foliage of Thalia dealbata on the right

Alisma plantago-aquatica with foliage of Thalia dealbata on the right

The best gardens are all about connections and the garden here at Elmstead Market is full of them. Talk to Beth and she will very quickly tell you about the importance of her husband, Andrew’s work as a botanist in identifying plants from all over the world that had the ability to grow together. She will tell you too about her friendship with Cedric Morris, and you will find his collections and selections in the garden if you dig a little and ask the right questions.

My notebook filled rapidly – the nine foot Allium ‘Purple Drummer’ and Agastache ‘Blue Boa’ amongst Deschampsia caespitosa ‘Schottland’ – and it continued to do so in the nursery where we had a behind the scenes look at the industry of the place and saw at close quarters all those treasures that have gone out into the world to fuel passions. My order of new-to-me and untested plants came together without hesitation. Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Schottland’, Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’, Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’, Salvia verticillata ‘Hannay’s Blue’ and Teucrium hircanicum to name a handful. They have just arrived, within the week, beautifully packaged as ever, bringing all the excitement that has been coming to me from this inspirational place for the best part of forty years.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 July 2017

The Woodland Garden

The Woodland Garden

The word on the street was that this year’s Chelsea Flower Show was a little lacklustre, suffering somewhat from the late withdrawal of a number of show garden sponsors. However, the show always has something to delight at if you look hard enough.

Although there are increasingly fewer of them, the specialist nurseries in the Great Pavilion show what real, impassioned horticulture is all about. I always head there first, notebook in hand, to find the treasures that might inspire a new planting, or add an extra something to an established scheme. It is impossible to resist some of the plants on display and, as I place orders for later delivery, I visualise the changes the new arrivals will make with excitement.

A handful of the show gardens caught my attention this year but, despite the reduced number, there were several which repaid closer viewing. I made notes on a number of new plants and well-considered combinations. These are some of the things that caught my eye.

I’m on a slightly unstoppable peony roll at the moment and, as well as ordering some tenuifolia hybrids, I hankered after these from Binny Plants.

Paeonia ‘Mahogany’

Paeonia ‘Mahogany’

Paeonia ‘Claire de Lune’ & Paeonia ‘Buckeye Belle’

Paeonia ‘Claire de Lune’ & Paeonia ‘Buckeye Belle’

Paeonia ‘Pink Hawaiian Coral’

Paeonia ‘Pink Hawaiian Coral’

And these from Kelways.

Paeonia ‘Blaze’

Paeonia ‘Blaze’

Paeonia ‘Roman Gold’

Paeonia ‘Roman Gold’

I always seek out Kevock Garden Plants, who supplied a huge number of the tangerine Primula ‘Inverewe’ that was one of the stars of my last Chelsea show garden. The delicacy and perfection of their display never fails to render me speechless. A garden fairyland that takes me right back to my childhood. Stella Rankin, one of the owners, told me that this year they had a new helper with a background in floristry set up the stand, and there were some sophisticated and bold colour combinations.

Primula florindae and Meconopsis Lingholm’

Primula florindae and Meconopsis Lingholm’

Meconopsis ‘Lingholm’

Meconopsis ‘Lingholm’

Primula japonica ‘Postford White’

Primula japonica ‘Postford White’

Semiaquilegia adoxoides

Semiaquilegia adoxoides

Corydalis calcicola

Corydalis calcicola

I also spotted these beauties on a nearby stand but, to my annoyance, forgot to note down which one.

Meconopsis baileyi ‘Alba’

Meconopsis baileyi ‘Alba’

Lupinus lepidus

Lupinus lepidus

Kniphofia pauciflora

Kniphofia pauciflora

There is usually at least one variety of foxglove on The Botanic Nursery stand (main image) that catches my eye, and this year was no exception.

Digitalis purpurea ‘Apricot’

Digitalis purpurea ‘Apricot’

Digitalis ‘Primrose Carousel’

Digitalis ‘Primrose Carousel’

Digitalis ‘Polkadot Pippa’

Digitalis ‘Polkadot Pippa’

Digitalis cariensis

Digitalis cariensis

And on the Harperley Hall Nurseries stand this one stood out.

Digitalis ‘Illumination Raspberry’

Digitalis ‘Illumination Raspberry’

In spite of our south-facing hillside site I can never resist the woodlanders, and have been planting for shade so that I can have just a few of my favourites. I am slowly building a collection of martagon lilies and so never miss a lengthy exploration of the Jacques Amand stand, my notebook quickly filling with new varieties I want to get to know better.

Lilium martagon ‘Arabian Night’

Lilium martagon ‘Arabian Night’

Lilium martagon ‘Claude Shride’

Lilium martagon ‘Claude Shride’

Lilium martagon ‘Sunny Morning’

Lilium martagon ‘Sunny Morning’

Lilium martagon ‘Terrace City’

Lilium martagon ‘Terrace City’

While I really wanted to get my hands on this hybrid lily from H. W. Hyde.

Lilium ‘Garden Society’

Lilium ‘Garden Society’

I have recently made a dry herb planting in the gravel between the house and the kitchen garden, predominantly of lavender, with salvias and a range of umbellifers for pollinators. I was on the lookout for some additions to lift the scheme and, although I already have Allium christophii in the mix, these sculptural alliums from Warmenhoven would definitely add to the feeling of ornamental production I am aiming for.

Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon

Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon

Allium ‘Green Drops’

Allium ‘Green Drops’

Allium scorodoprasum ‘Art’

Allium scorodoprasum ‘Art’

While I thought this thistle would also make a good companion in the gravel.

Galactites tomentosa ‘Alba’

Galactites tomentosa ‘Alba’

From dry plants to aquatics at the Waterside Nursery stand, where I visualised the pond in which I might plant some of these choice specimens.

Typha lugdunensis

Typha lugdunensis

Typha minima

Typha minima

Ranunculus flammula

Ranunculus flammula

Iris pseudacorus ‘Roy Davidson’

Iris pseudacorus ‘Roy Davidson’

Iris versicolor ‘Mysterious Monique’

Iris versicolor ‘Mysterious Monique’

Just as I was leaving the Great Pavilion I chanced across these two clematis on the Thorncroft Clematis stand, which I would love to find homes for.

Clematis mandschurica

Clematis mandschurica

Clematis integrifolia ‘Ozawa’s Blue’

Clematis integrifolia ‘Ozawa’s Blue’

Of the show gardens James Basson’s Best in Show winner grabbed the attention. Bold and confident hard landscaping was colonised by a huge range of native Mediterraneans, whose weedy grace was a great foil for the beautifully detailed, monumental stonework. The rectilinear walls created some carefully framed moments.

Charlotte Harris‘ Gold Medal garden for the Royal Bank of Canada was an exercise in stylish restraint. Inspired by the boreal forests of Canada the space was held by a group of jack pines (Pinus banksiana), which sheltered a graphic pavilion of burnt larch and copper, creating a potent sense of place. In contrast to this evergreen presence the woodland and waterside plantings were transparent and delicate, with some exquisite combinations.

In the Artisan Gardens category the yearly return of Ishihara Kazuyuki is always one to be celebrated. As is the beautifully-crafted way with all things Japanese, the fully-planted, green walls at the side and rear of his ‘Gosho No Niwa’ garden were more magical than the front, conjuring somewhere tranquil and dreamlike

To fill the holes left by some of the show gardens that were withdrawn, Radio 2 produced five Feel Good gardens relating to each of the five senses. Given the exceedingly short time frame of two months in which the designers had to design, source and build these gardens, the standard was extremely high, which made it a shame that they were not included in the judging.

The garden representing sound, designed by James Alexander-Sinclair, was a lush green oasis, punctuated with a staggered series of rusted troughs. Speakers mounted beneath the surface of the water vibrated to create ripples, splashes and gentle undulations depending on the bassline of the song being played.

The Anneka Rice Colour Cutting Garden was designed by Sarah Raven, who had somehow managed, in the time available, to assemble a riotous potager bursting at the seams with her signature jewel-coloured plantings.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 May 2017

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage