Simon Jackson (above right) is a pharmacognosist and cosmetician who is passionate about creating personal products that are derived from scientifically proven, sustainably produced active plant extracts. After a long and wide-ranging career as a scientist, researcher and cosmetic product innovator, for the past two years he and his husband, John Murray (above left), have been developing a new range, Modern Botany, using British native plants grown near their home in the West of Ireland.

Simon, you have taken an interesting and varied route to where you are now. Can you give us a brief explanation of where your interest in the therapeutic uses of plants started and your training ?

Interesting? Varied? I think they call it a career portfolio nowadays! OK, how long do we have? As you can imagine I’ve got a lot to say on plants and their therapeutic uses. I guess it all started in Lincolnshire. I grew up in a small village and my love of plants came from my grandmother, Cath Jackson. She was a keen amateur gardener and she taught me all the Latin names of plants when I was very young. She had a small plot of land and was very proud of all her plants and I used to help her gardening. She had a beautiful allium that came up year after year, and it was quite unusual in the early ‘70’s to have such unusual plants. She introduced me to

Sir Joseph Banks, a famous Lincolnshire botanist. There is a big monument to him in Lincoln Cathedral, and his home town of Horncastle was close by, so the seed was planted.

Skip forward about 20 years, and I found myself studying at Manchester Metropolitan University in 1989. I did a course in Applied Biological Sciences and specialised in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. Back in the late ‘80’s it was called Plant Defence Mechanisms. When plants are put under pressure externally or attacked by herbivores, they excrete defence chemicals. Salicylic acid is one of them. It has a bitter taste so wards off any herbivores, but it also has medicinal properties for humans too. Aspirin we call it. It was here that I learnt about ethnobotany, and how traditional cultures use plants. For example, it was the native Americans who used willow bark during childbirth as an analgesic to help with pain relief. I just thought this was amazing and so, as part of my degree, I undertook an expedition to Indonesia. The year was 1992, and it was in the middle of all the atrocities in Timor, but I was quite gung-ho even back then, and just wanted to learn more about plants and their traditional uses.

We lived on an island called Sumba. It was very primitive back then, no luxury hotels or surf dudes like there are now, but I took part in what was one of the first pharmacy conservation projects in an Indonesian primary rainforest. I was cataloguing species of plants around the island and understanding from the locals any economic uses they had, which could be medicinal, or as dyes or fuel or even as building materials. The aim was to set up some sustainable practices for harvesting these plants.

It was on the island of Sumba that I remember being introduced to a village chief. I had wandered off into the rainforest one day a bit too far on my own away from base camp, and he found me walking in the wrong direction (I have a terrible sense of direction) and brought me back to camp on the back of his Sumbanese pony, an indigenous breed of horse on the island. Seeing the hornbills flying back at dusk and the Sumbanese green pigeons (they look like parrots) it was here that I learnt from him about the traditional uses of plants, and it was here that I had my cathartic moment and realised it was traditional plants I wanted to study. That’s why I had majored in Drug Discovery and Toxicology.

I also worked in the Herbarium in Bogor, and met Professor Kostermans, an amazing ethno-botanist, who regaled me with all his stories of expeditions in Indonesia, Borneo and Sumatra. He was a POW during the war and only survived by learning from the locals how to utilise the native plants for food and medicine. And that was it. I was hooked.

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade.

Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers.

Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘

De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘

De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the

ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the

American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the

Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

The ACEER Camp in Peru

The ACEER Camp in Peru

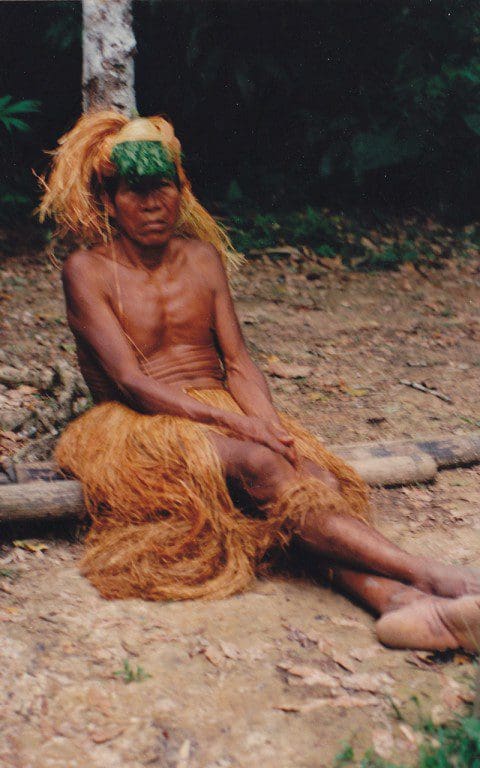

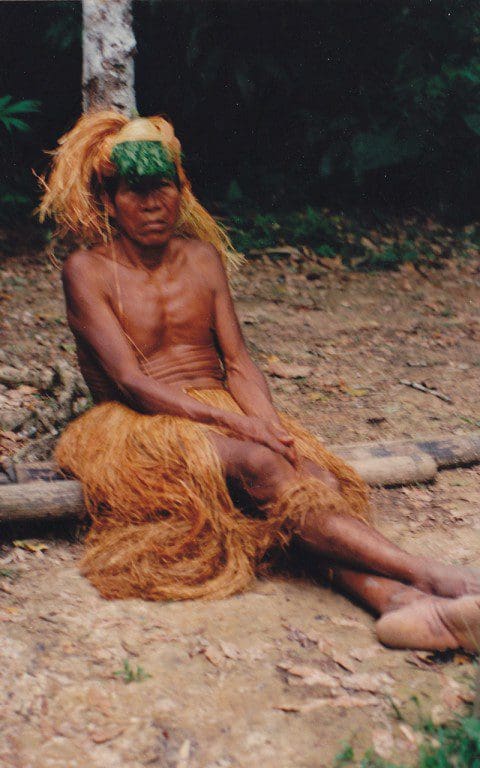

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on

Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched

Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for

Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘D

octrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a

bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

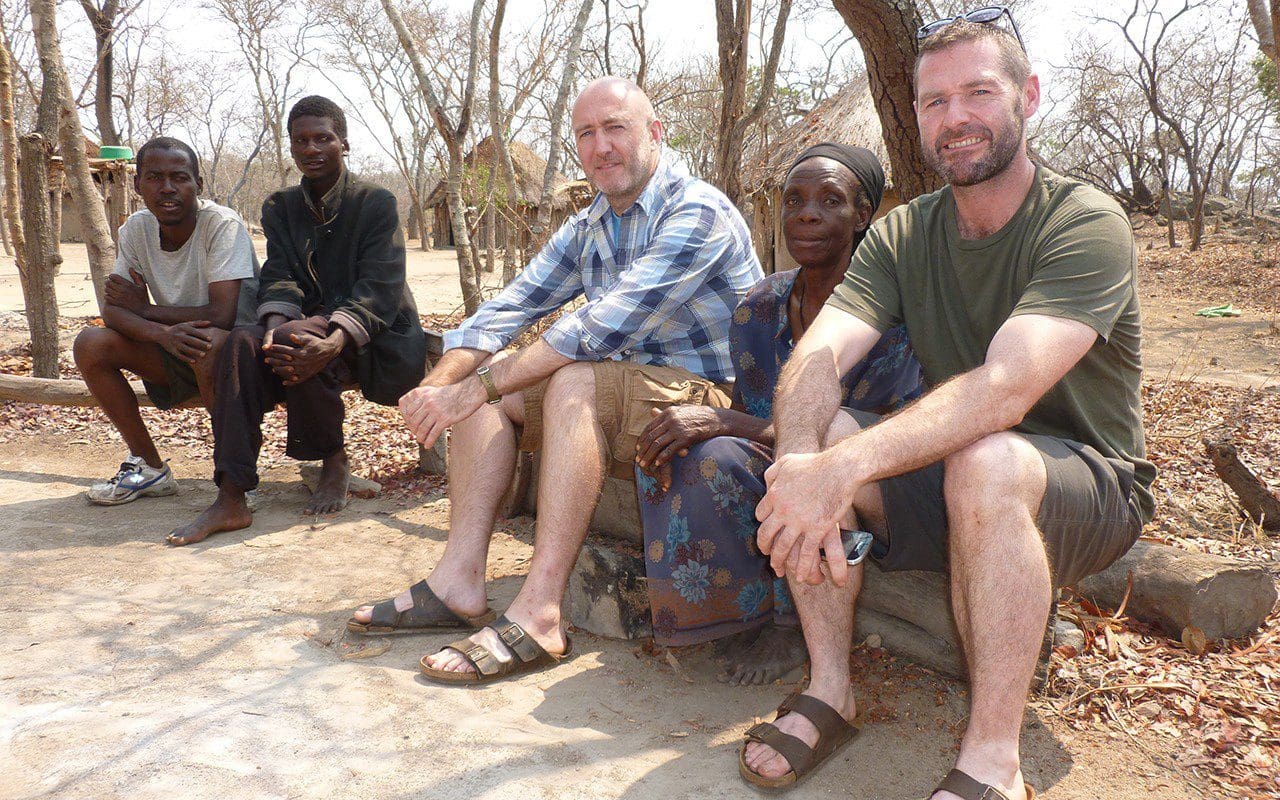

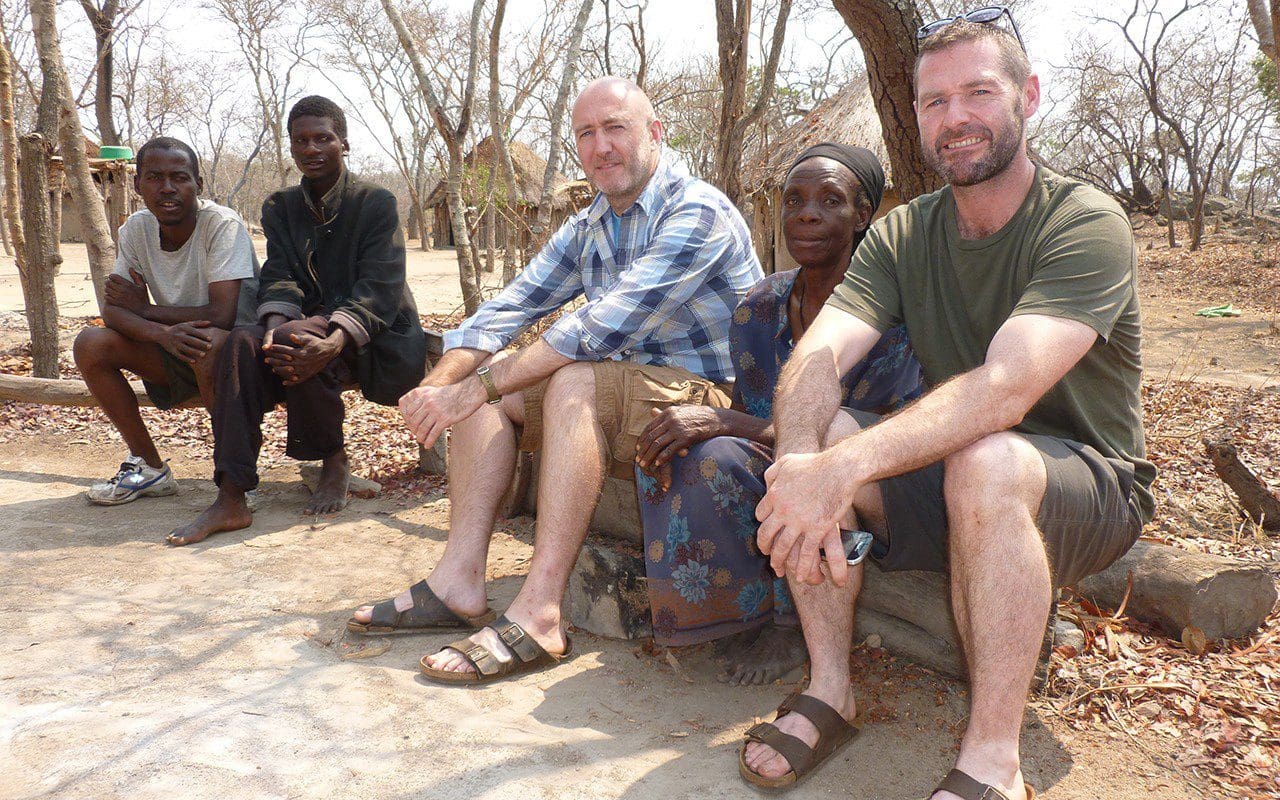

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (

Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the

CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (

Plantago major) and bog cotton (

Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (

Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

The ACEER Camp in Peru

The ACEER Camp in Peru

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018

Previous

Previous

Next

Next