Lucy Augé is a Bath-based artist who has an passionate interest in the variety of flower and plant forms which she paints with Japanese inks on a wide range of specialist and vintage papers. Her intention is to capture the ephemeral and fleeting moment. We met last year and, after introducing her to the Garden Museum, she showed some of her new tree shadow paintings there earlier this summer. Since June, Lucy has been coming to the garden at Hillside to capture a range of the plants here on paper.

How did you come to be an artist ?

I always wanted to be an artist, even from being a child. For my tenth birthday I didn’t want a party, but wanted to go to Tate Modern, as it had just opened. I think my mum thought, ‘Oh God. Choose another career path !’. I had always been creative at school, I was never really academic, so I got funnelled down a channel into being ‘artistic’. That then followed me through to college, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist, so I did graphics, and thought I’d go into magazine design, as I had a passion for French Vogue at the time as it was so well art directed.

Then I had a really bad brain injury from a fall, and that left me very, very ill, at home. I couldn’t go back to university. I couldn’t do much, as I was having four seizures a day, and thought, ‘OK, life’s over’, but then I started gardening with my father, and that’s where I started noticing – I was going at such a slow pace, because I was so ill, I’d have to be carried down to the garden – and I started noticing things more, because I didn’t have any distractions. I didn’t have a phone for two years. Not that I was cutting myself off, I just didn’t need it. So I just started looking at nature all the time, and then I just started painting it. Repetitively. Or I was watching gardening programmes on repeat, because I wanted to know more, all the time. So, that’s where, through the illness, I got the passion for gardening and my painting.

When I finally went back to university I just felt it was very redundant for me. I went back to the graphics course as I was already a year in and because I don’t really like to give up, but I knew the tutors didn’t really like my work. They were looking for a very graphic, computer-generated style of work, and I then generally only worked in felt tip, keeping it hand drawn, but still trying to fit in with the current look that was around at the time.

So what happened after university ?

I got picked up for projects while still at university and, when I graduated, I did packaging design and worked with Hallmark, but I quickly knew I wasn’t an illustrator, as I can’t draw just anything and my passion lay with nature and studying that, rather than drawing a family of badgers eating cake. No joke, that was an actual commission.

The 500 Flowers exhibition came about after a month I spent in LA in 2015, where I had a meeting with the art director at Apple of the time, who had offered to mentor me. He set up a meeting with a carpet designer who I was supposed to do collaboration with. However, when he met me he told me that I wouldn’t be an artist unless I married someone rich, and that he would only work with me if I got someone to buy one of his rugs.

I was enraged by this and thought I was tired of waiting for someone else to launch my career for me. So I came home determined to make an impression alone, booked a rental gallery space in Bath and put on my first show on my own. The idea originally was to paint a thousand flowers, but that was near impossible in the time frame I had set myself. My brother calculated I would have to complete one every ten minutes ! So I painted five hundred, with the aim of painting every species that I came into contact with.

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

You produced all of that work and organised the exhibition yourself. What was that experience like ?

Well, I had five hundred A4, individually painted ink drawings, which I had completed in three months, and that both evolved my style and I became very confident at drawing. I also priced them at £40 each, which I think some people thought was madness, but at the same time nobody knows you, you have no reputation, and so £40 can seem like a lot for someone, but it was great because it made it affordable so that people would buy maybe nine or twelve at a time. An interior designer, Susie Atkinson, bought sixty. And so it got my name out there, because I was affordable.

The exhibition took place in Bath and I made sure I had beautiful letter-pressed invites. I invited everyone I’d ever met, contacts I’d made on Instagram or through business or who had shown an interest in my work. I invited people who I really admired for their work, which is why you and Dan got an invite. I just wanted to show people that this is what I do, this is my passion and if I fall flat on my face and no one comes and nothing sells, at least I would have known that I’d given it 100%. And then I’d have gone and got another job !

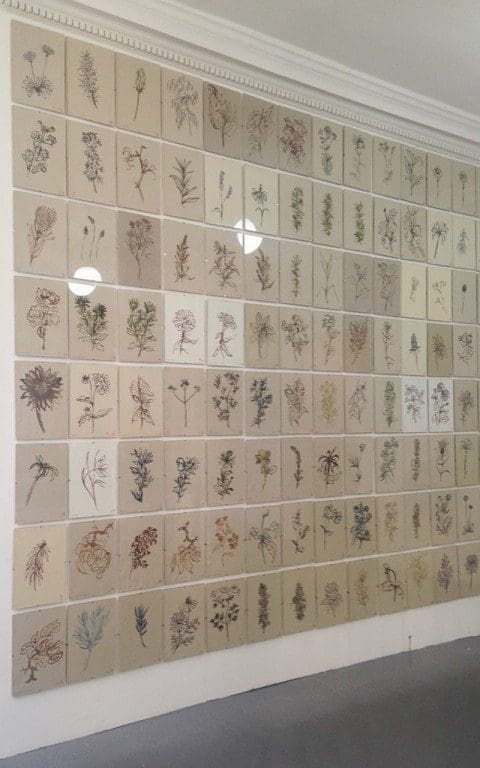

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

But it worked out in my favour. I had a queue out the door on the first night. I sold over eighty in the first couple of days. Then House & Garden emailed me to ask if they could have nine for their show, which the editor ended up buying. The assistant editor then bought another nine, and she put them up on her Instagram and I ended up selling out in five months. That then led to shows in Japan, San Francisco and elsewhere. It confirmed to me that, yes, you are on the right path, you’re doing the right thing, and the proceeds of that first exhibition went towards buying my studio. Before then I was working in a barn with no windows, no natural light, no loo, and so that exhibition was my make or break. Otherwise you can be creating, and calling yourself an artist and saying ‘This is what I do for a living.’ and yet you’ve never really put yourself out there, and so I thought, ‘baptism of fire’.

Then I started getting commissions from people to go and draw on their land, their flowers, which was really great. The best of those was for Gleneagles, which was the highlight of my career. I was flown up to Scotland, where I’d never been, and stayed at the Gleneagles, which was an amazing experience, and I went round the estate and drew all of the plants that were there at that time, and they are now hanging in the American Bar. And it was just so nice to know that people understood what you do.

Were you starting to charge a bit more for them now ?

Yes, I did raise my prices. Although I didn’t charge a lot because I wanted people to have the chance to invest in my work. I come from…my father grew up with no money, but he was always passionate about art, and just wanted someone from his background to be able to go, ‘I’m going to invest in something. Something beautiful.’ So that they can own real artwork. And I think that is a real gift to be able to do that. Especially as I had five hundred ! And the consequence now is that they have travelled all over the world. I love that there are some in Singapore, and some in Brazil and I don’t think I would have got that kind of international reach if I had not priced them so competitively. Of course, now my prices have gone up and I don’t need to produce as many. My last catalogue only had twelve paintings in.

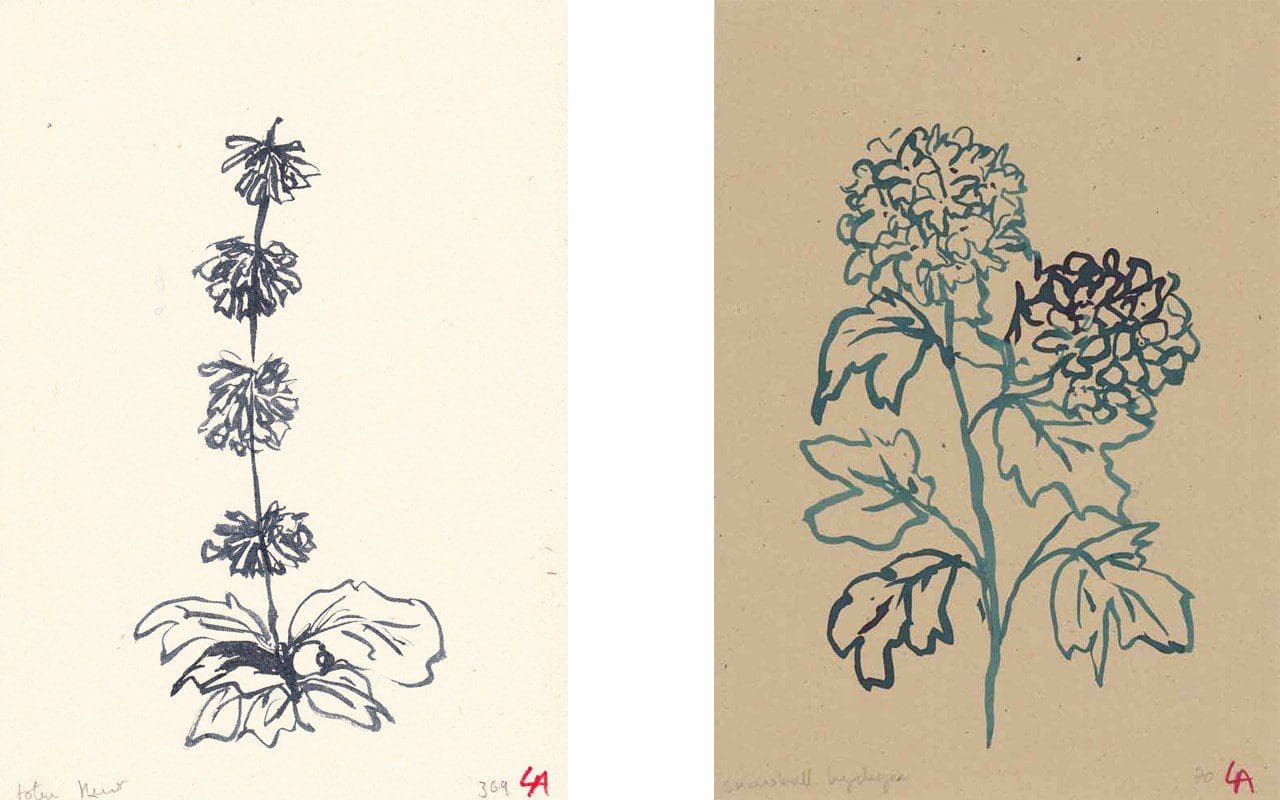

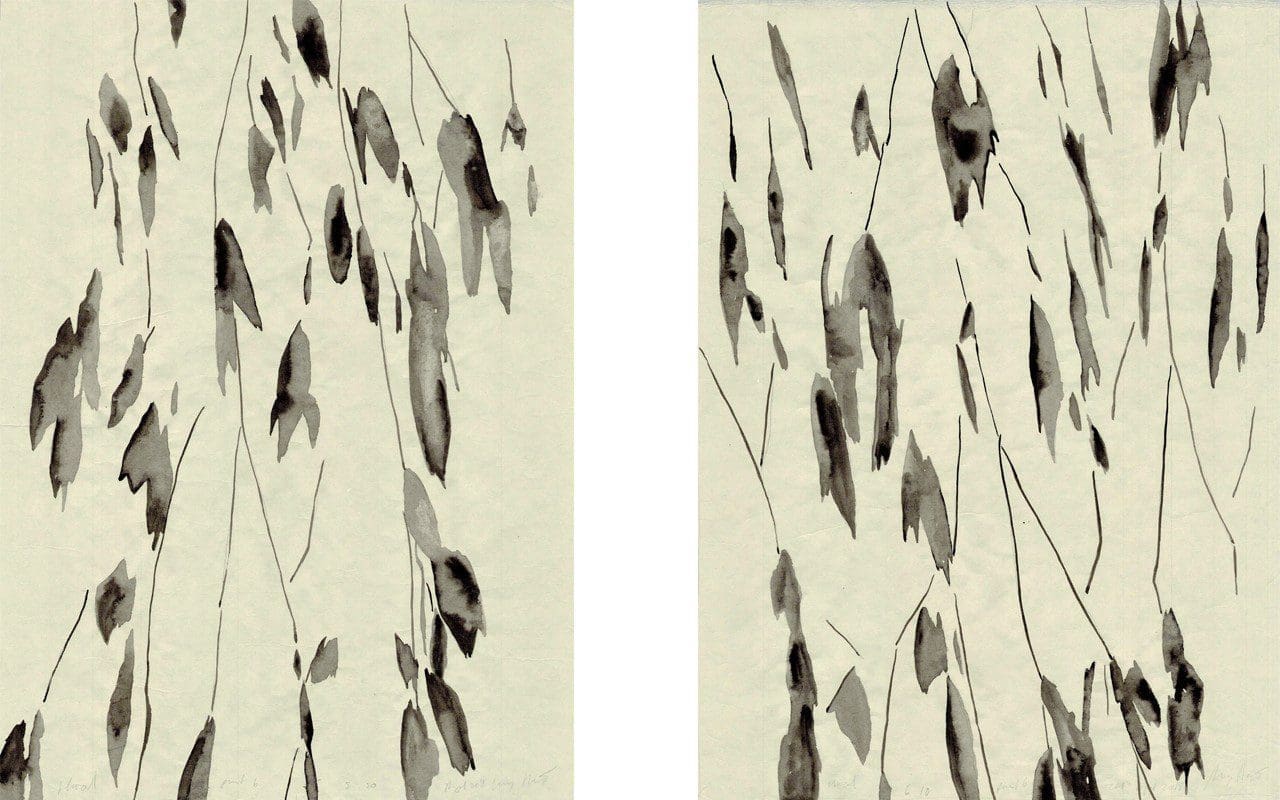

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

What was the medium you used for the 500 Flowers paintings ?

Ink. On antique paper.

I’ve seen some of your work which is very highly coloured and looks like it is done in felt tip ?

Yes, that’s right. That’s when I was still trying to be an illustrator. With those I was trying to fit in with the norm, so everything was very highly coloured for editorial. I would say that that was the only time I have ever tried to fit in. It worked for the clients to a point, but I kept being told, ‘Your work looks too much like you. There’s something to it, but it’s not commercial enough.’. So I gave it a year, doing that kind of work and I just grew out of it very quickly, because it wasn’t me.

There appears to be a strong Japanese influence in your work.

I love Japanese and Chinese art. I’ve always loved Japanese and Asian culture, so it’s always been in the background. Anything from there I could get my hands on I wanted to have a look at it, absorb it. Then I saw a show of Chinese paintings at the V & A, where I learnt that they were painting with natural pigments, so with copper and iron and earth and plants, and it just made this wonderful colour palette. So I found some Japanese inks that have that same antique colour palette, and it just felt much more me. It’s hard to put my finger on it, but it just started to fit better with the kind of images I wanted to make. And with the paper. I had never wanted to work on white. I had this antique paper, which had been in my godmother’s attic, which had the same feeling as the old Chinese papers I had seen, because they are made entirely from natural elements. So my choices were about aspiring to that antique colour palette. The other thing that struck me about that exhibition was that the artist was always invisible. The painting was never about the artist, it was about nature, landscape, weather, the seasons. It was about the everyday. And I thought, ‘Yes. Art can be like this.’ Because as I was growing up when everything was about high concept or shock, shock, shock or politics. The stranger the better. How far can you push it? And looking back at older art – one of my favourite artists is Monet – was deeply unfashionable and seen as suspect. But I love how he could just paint waterlilies and the resulting painting becomes this charged, emotional landscape.

Is that one of the reasons that you didn’t feel you could really be an artist ?

Yes, completely, and it’s one of the reasons I considered commercial art to begin with. Also I was never really encouraged at school, bar one teacher, to pursue my art. You were told that you needed to fit in. And I think as an artist you do need some kind of validation that what you are doing has value and that this is what you are supposed to be doing. And I never really got that until I put myself out there and had people say, ‘We want what you make.’ Because otherwise you can be drawing for just you – and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that – but you do have to decide that you are going to be an artist, and I made that decision after the success of that first exhibition.

I could have gone in one of two directions. I could have just put my flowers on anything and gone down the commercial route, or choose to refine the work and make it more considered. I have had a few commercial collaborations, but I have been very choosy about who I have agreed to work with or who I have approached. And I then reined it in and have now moved my work away from it, as people lost the meaning behind what I was trying to do. So they just wanted a picture of a lily as their daughter was called Lily, which is fine, but it missed the ethos of the work.

Which is ?

Seasonal observation through nature and plants. Forgotten moments. The immediacy of right now. I always found it interesting that the first pictures to sell out always are the ones of weeds. Those are the ones that people really want. I think because, as soon as you paint them, and strip everything away, you can see the beauty in them, and the fact that they are so mundane, but the painting elevates them. Honours them.

Do you know that there are 56 seasons in Japanese culture that relate to the flowering times of 56 different plants ?

No, I didn’t. How fascinating. I can so relate to that. I get quite anxious at the possibility of missing things. You know, like cow parsley. I’ll have a great idea, and then two weeks later I’ll have the time to get onto it, and all the cow parsley is gone ! So now I prep my paper in advance and cut it to the size that I want so that, when that moment presents itself, I can just say, ‘Here I come !’. That’s why when I came to your garden I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s definitely going to be, sorry to say for you, a much longer process than I had envisaged, as I now would really like to be there in different seasons.

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

What does your work mean for you personally ?

Very generally it just gives me that quiet time. You don’t have to think about anything else. Once you get into a process – it’s a bit like gardening in a sense – it gives you that same mindfulness combined with productivity, which makes me feel at peace. You’re just drawing, or gardening, and that’s all you’re thinking about. And then sometimes you’re not even thinking at all, but are completely lost in the process of activity. That’s what I really love about what I do. It’s quite addictive. It empties your mind and is very meditative. I’m a worrier. I do worry too much and it’s quite nice to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to think about anything now.’ And I’ve always been quite confident in my own work, so it feels like a very safe space when I’m creating. And once I’m happy with it and happy to put it out in the world, it’s done and I can move on.

Until then – and that’s why I have my studio away, remote. I don’t want to hear everyone else’s opinions – I don’t actually show anyone my work until it’s at a certain stage, which is almost finished. It gives me a degree of freedom and escapism. Which is why it didn’t work for me as an illustrator, because someone else is dictating what you’re going to draw, your process is held ransom by deadlines, and I’ve never been any good at being told what to do. Ever. I will question and question to understand why I should do something. Just because I’m curious, but having it be just my own work I can ask my own questions and be curious about where it’s going to go next, how am I going to paint it. And I know what I am looking for, rather than what somebody else is looking for and wants me to produce. I do find it difficult when someone says, ‘I have a tree in my garden. Can you paint it ?’, because the tree might not be the thing in their garden that I would want to paint.

What are you looking for ?

In paintings I think it’s a stillness. I really want to portray stillness, or a captured moment. So everything has to be painted from life, because it feels fake otherwise. Sometimes I do draw from photos, but you’re just not capturing that moment when that leaf on that plant might have been at an awkward angle. You might not have seen that from a photo, so that’s really interesting to explore.

The 500 Flowers were all painted from life. Firstly, all near to me and around the studio, so a lot of wildflowers, but also some bought flowers, and that’s how I got in touch with Polly from Bayntun Flowers, because I looked up ‘local cut flowers’ online and saw what she was doing and I thought, ‘Brilliant !’. She had amazing heritage varieties and luckily, when I asked her if I could visit to paint, she said, ‘Yes. Come on round!’. I was like a child in a sweet shop. The first day was so exciting I must have made about forty paintings in one go. I would normally paint about five or ten. But the garden there was just chockablock with species, lots of which I hadn’t seen before, so it was very exciting and it got me up to five hundred !

But then it was hard when the winter came. I wasn’t aware of how much I would suffer. I became quite, ‘unusual’ in the winter, because I panicked and thought, ‘What am I going to draw ? Everything’s over. My work’s not good enough.’ It was really tricky. You’ve been doing all this painting and you’ve got this absolute high from painting all these things, because there are endless possibilities and inspiration in the summer, and then my first winter I didn’t know what to do. I was really looking and trying to paint winter, but really everything is just dormant and that’s when I realised I have to know what I’m going to do when winter comes. Not hibernate.

So now in the winter I paint a lot of dried leaves and stuff like that. The first winter I was so busy, doing commissions and collaborations, that I didn’t really notice. It wasn’t until winter 2016, a year after the show, that it was total panic. A flower desert. I thought maybe it was time to do some abstract stuff, get back into illustration. It was bleak. And then there was stuff going on in my personal life, and what’s going on in my personal life does feed into the work. If I’m having a grumpy day I will most likely pick out a mopy looking plant. It’s weird. I didn’t even realise it till someone else came to my studio and said, ‘This is all a bit melancholy.’ It’s frees such an subconscious part of your brain when you’re drawing, you’re not really thinking, you’re just observing. When I saw how my moods were feeding into my work I wanted to explore that more.

The paintings that I relate to the most, like Monet’s waterlily triptych, that he painted as a reaction to the war, is so powerful and emotive, and it is ‘just’ waterlilies, and I thought I would like to try and harness that emotional connection more and be more aware of it when I am working. So the tree shadows that I have been doing most recently came about because I had drawn so many flowers – I mean I was well over a thousand different flowers by now – and I was starting to fall out of love with them, even though there were commissions paying my bills. I thought, ‘I’m on the way to making myself into a performing monkey.’. I was getting set flower lists from people, with direction on paper and ink colours and I thought, ‘I didn’t start doing this to make ready-to-go flowers.’. It wasn’t me, and felt like I was heading back into illustration territory, which I had dragged myself out of.

But then it all changed because the farmer that owned the land that the barn I was renting died and so my studio tenancy went with him. I also had some financial worries. I didn’t want to paint another flower even though it was full on summer time and I was just lying in my studio taking a nap and I could see the reflections of the trees in the glass of one of my old pictures. And I thought it was interesting. I had also been experimenting with totally abstract ink paintings, which I would cut up and make into smaller single frames. But that didn’t fit in with anything that I was doing. But I started to think about how I could bring these things together. I started trying to draw the outline of the leaves onto the frame, but that didn’t look right. Then I started drawing outdoors, which I had always done. All five hundred flowers were drawn outside. But I couldn’t get a high enough outline definition.

That’s when I realised that everything moves so quickly. I would go and get my water bottle from the studio and, by the time I got back, the shadows had moved and the picture was different. That’s when I also started noticing the weather. Timing was everything. Before that I had just been aware of when each flower I was painting bloomed – this in when the roses are here, this is when the daisies look best – but not the bigger picture. When I was drawing the flowers I was more aware of the different varieties, because when you watch gardening programmes and learn that this is what a rose looks like, this is what an angelica looks like, and then when I would go out into the fields I would think, ‘Well, that has the same leaves as a rose. That looks like an angelica.’ And so then I was learning, without any books or anything, about those wild plants. Even though I didn’t know the name I was able to match them up.

What I was finding when I started doing the tree shadows was that , even when the shadows distort, they each have a particular look. Aa certain space between the leaves. The reason I like painting hazel is they have a lot of space between the leaves. I’ve tried painting quite a few different trees, but have found what works and what doesn’t work for me, for my aesthetic. I’ve also learned that, at four o’clock, you won’t be able to get hold of me, because the phone goes off, because that is the time I’ll be painting the shadows. That’s one of the things I noticed at your place. It wasn’t four o’clock. It was later. More like five thirty, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference, because that’s when you’ve got the high definition of the shadows, like on the irises that I tried doing. And where your site is so exposed the light seemed to move so quickly. I only had a half hour window, and that was it. Whereas where I am I can start at four and not finish until seven. The angle of the image changes, but at yours I was surprised at how the time made such a big impact. It’s taken months to understand that. When is the right time to draw. What is the best weather.

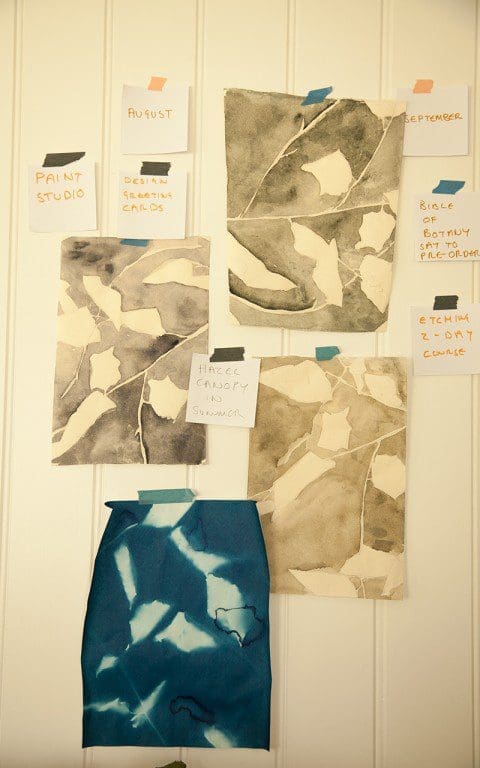

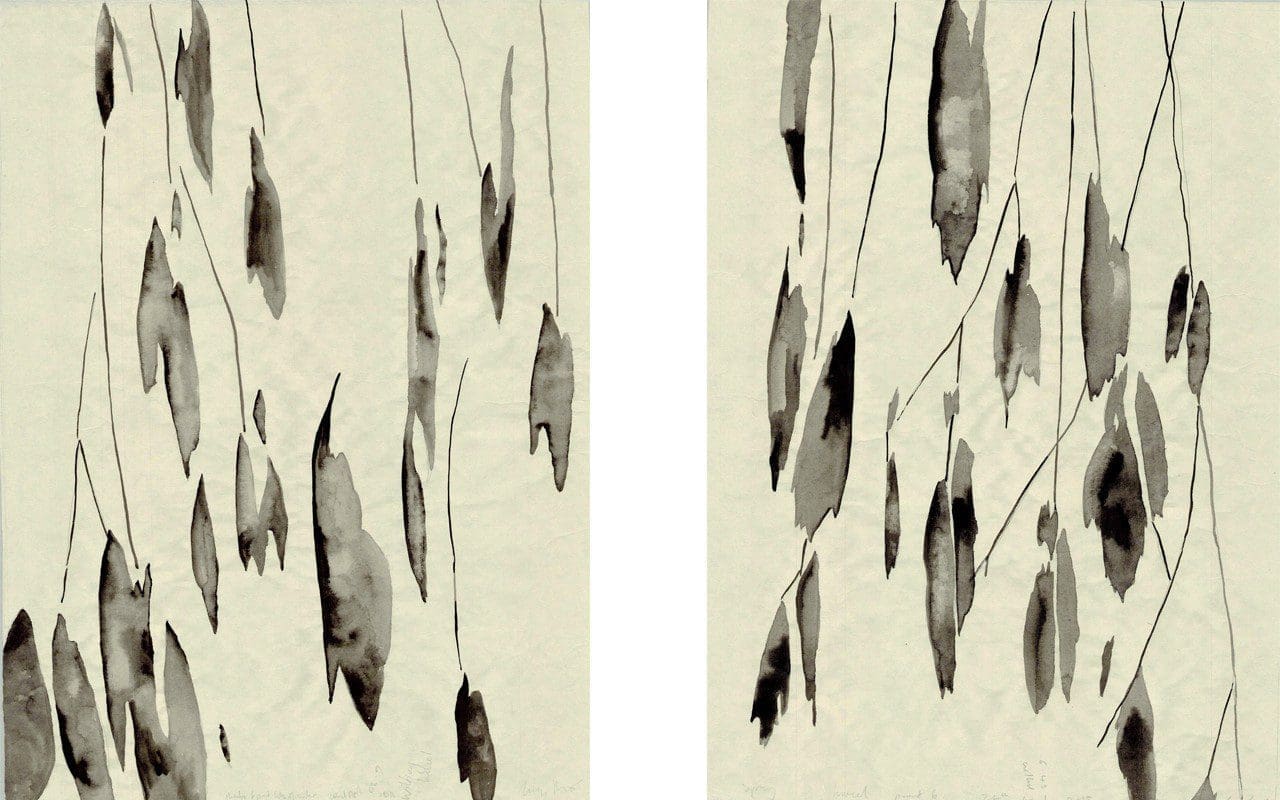

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

When did you start doing the tree shadows paintings ?

August last year. It was purely by accident. I had some leftover scroll paper and I had this birch branch and was trying to paint up into the canopy inside the studio. So I’d hung it up and then I saw that when the sun came in through the window, there it was on the ground. So I thought, ‘Oh, quick ! Get it down. Start drawing.’ I wouldn’t say that I’m drawing the outline, but more what I saw, because things move so quickly that you can’t get the exact outline, so there is a bit of interpretation involved, but I still want to be quite true to what it is, and if what it is turns out to be an awkward picture, I quite like that uncomfortableness.

So that first shadow painting, and I know this sounds cheesy, made me feel re-awoken again. I thought, ‘OK. Let’s restart.’ It was a risk, giving up on my flower paintings, which was bringing me in income, and then you think of going to your audience, who know you for your flowers, and saying, ‘I’m doing tree shadows now.’ But, the response was really, really positive. And it has been encouraging to hear people say, ‘You know I really liked your flower paintings, but I lovethe tree shadows.’

I think it’s because they feel more like art to people, whereas the flower paintings were more illustrative, the tree shadows are more abstract. But I think that doing the 500 Flowers gave me some validation, which means it is easier for people to feel comfortable with the change in direction.

When I was trying to capture a landscape through paintings of individual flowers – this is what grows here, this what I have seen and recorded – when I was in Scotland the flora there was very different, and it created en masse a very different painting. Different shapes and texture. Quite thistly, spiky plants, due to the hardier conditions up there. But not everyone got that, whereas everyone seems to get the tree shadows. I’m just really enjoying exploring it and see where it goes next.

I tried for two months earlier this year trying to capture the light coming through the canopy and it just didn’t work. Everything is a result of where I am working. My studio was too hot to work in, and so I was working under a tree – it was a walnut, which had a range of different colours in the leaves – and I was trying to capture all those variations in colour and collage them together, all in ink, in different gradients. I tried black and then green and it just wasn’t working, so I slightly felt that I was trying to – I’m always trying to come up with new work, a slightly ridiculous pressure to put on yourself, really you should just give yourself more time, so now I have gone back to doing the tree shadows. So yesterday I completed three paintings, which was a relief, because I got a bit stuck for two or three months. I do want to come back to the light through the tree canopies, because it’s been an obsession of mine for ages, since I was a kid really, when you were lying on your back on the grass looking up into the leaves with the sunlight coming through, but I can’t capture the light at the moment with the medium I’m using, so that’s why I’ve started making etchings, because the whiteness of the paper and the black ink, which becomes very matt, seems to be doing the job.

What are the challenges of your way of working ?

The etchings came about through the need to fill the winter gap. I was drawing in the winter sun, but it didn’t cast a good shadow, which I hadn’t realised, because the angle of the sun was too low. And it was a really grey winter last year, so I was waiting for the sun that never came. I did try using a lamp in the studio, but it felt wrong. It was impossible to get the light at the right angle and it felt like faking it. I am interested in capturing an ephemeral moment, not a frozen moment that doesn’t change. I have tried working from photos of shadows I’ve seen when out and about and projecting them onto the wall of the studio, and again it just didn’t feel right. I wasn’t capturing that moment that the camera had captured. And I enjoy the process of being really spontaneous. Just yesterday I had a small window to work in because the clouds were coming, and I was moving around this mock orange branch, and then the sun went, which was my fault for taking too long, which takes me back to that whole thing of not thinking and just being in the process. Every time I overthink it, it feels like I could be on that painting for weeks, and I’m not really like that as a person, so it would feel unnatural to do that.

By working with the sun I have got to know more about the passing of time, changes in daylight and seasonal changes. So I now know that autumn is coming up to peak season, because you get those amazing long shadows, which I find quite exciting, alongside the anxiety of knowing that I’m running out of time. I did do some painting in Thailand last winter. Paintings of palm trees that just looked like palm trees, and I found that quite interesting, because I didn’t know the Thai landscape, I didn’t know Thai plants, and I realised I am happier painting the familiar. Someone asked me recently why I paint hazel, and it’s simply because it’s in the hedge at the back of my studio, and it’s abundant. When I came to your place, again it was just complete overstimulation. There was so much, and I didn’t know what to choose, and your garden is very much a changing landscape. You can leave it for two weeks and come back and there will be a whole different colour palette. So when I came to your garden it just felt wrong not to paint flowers, even though in my mind I thought, ‘No more flowers. I’ve painted enough.’ It was the first time I felt like I actually wanted to paint flowers again, because I was discovering new things again, So that is something I’d like to explore more in your garden, but I need to get more used to it, as it is a whole new territory.

You told me that painting in our garden has opened up a new way of working for you. How ?

Well, the summer we’ve had this year has been very unusual. We don’t usually get weeks on end when it is just sunny every day, and I just felt like I needed to mark that. To capture the sun, and capture the flowers. So I thought, ‘How can I do that ?. So what I have noticed about your garden is that it has a lot of different shapes. All the plants have their own identity, and they all hold their own in the beds, none of them get lost. So I wanted to capture the shape of the plants, but not in ink.

With the etchings I did last winter of leaves, you just got the silhouette, and so I tried painting the silhouettes of some of your plants directly from life, and I just didn’t like the feel of them, and then the light was so amazing that that became my focus. So I started exposing the shadows onto cyanotype paper, where you are directly capturing the light on the paper. I’d first done this a few months earlier and was really interested in the process, as it produces images that are almost like abstract paintings. In some you can tell what the plant is, but in others you can’t and I like that. So the first time I tried it in your garden I was too scared to get close to the plants in the beds, and so I took the deadheaded rose cuttings off the compost heap, because I could just put them onto the paper and allow them to fall in their own way without me arranging them. I also like that element of chance. And I was also very influenced by the things you have at your place. Quite a lot of elements from Japan, a lot of natural materials and a lot of craft. And I just felt that etching, which is a craft, was a more appropriate response to the site.

So I want to create a series from your garden, but I would also now like it to be a longstanding, seasonal thing. So this summer it has, so far, been about the roses, which were such beautiful, old-fashioned looking varieties. I would like to come back at harvest time and see if I can capture that, when everything is going to seed. And rosehips. I just really want to document the seasons, as I don’t think people look at things closely enough and I think, when you’re more in tune with the seasons, you understand the world and our place in it better.

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

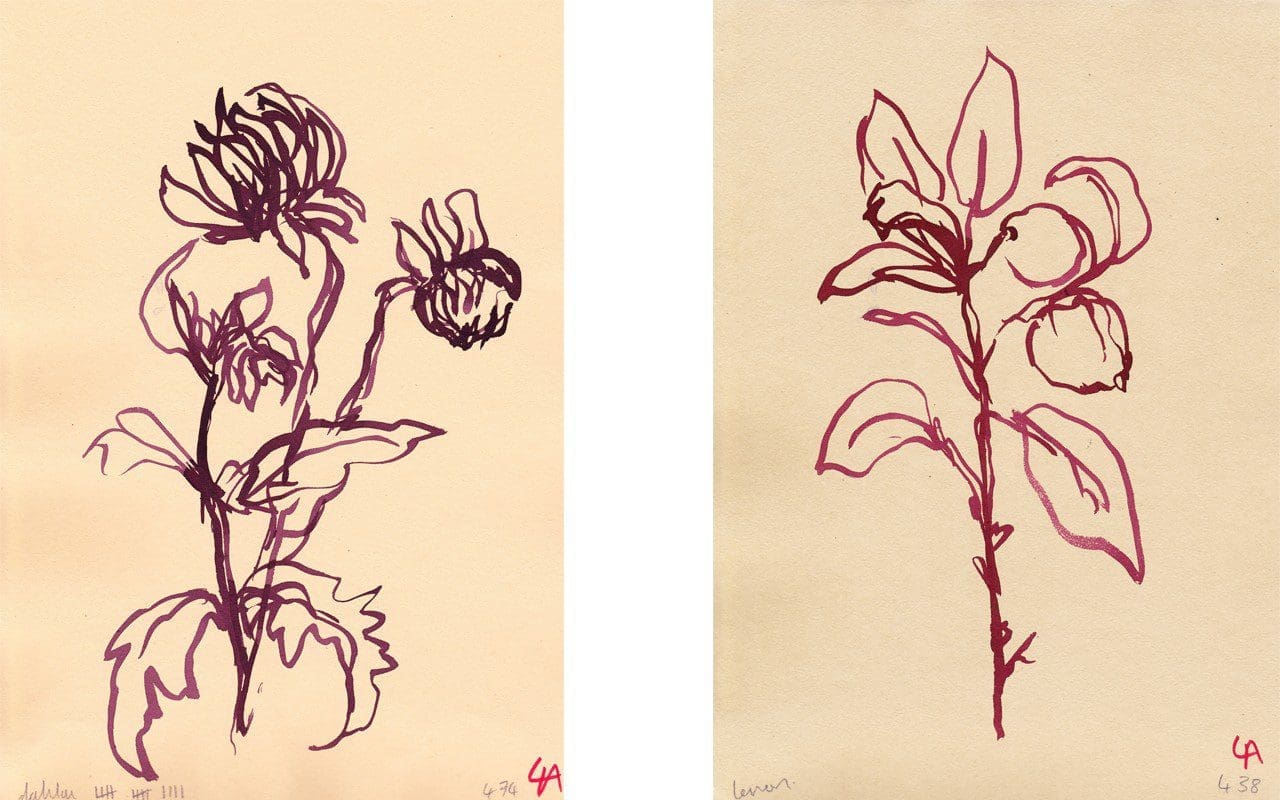

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

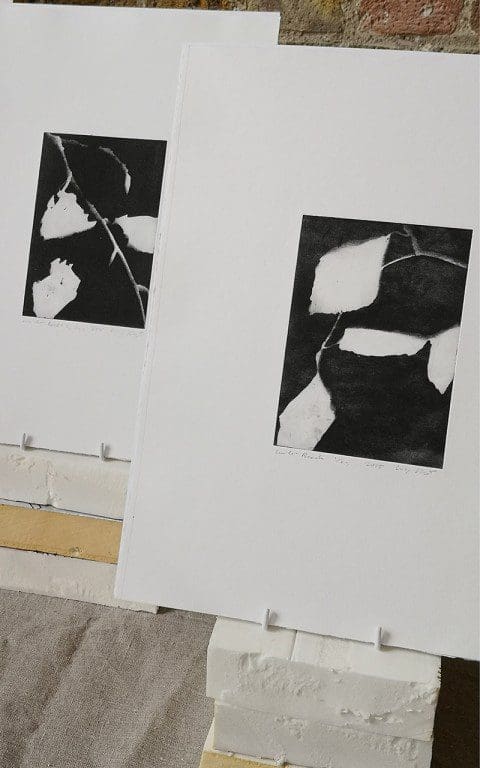

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

After last winter do you have a new approach for this coming winter ?

Yes, winter will be the time when I execute all of the etchings I am going to make from the cyanotypes taken in your garden. The process of creating etchings is quite time-consuming and complex, and it is still very new to me so I would like to spend more time getting more experience of that process. So at the moment I am just amassing lots of exposures so that I have plenty to work with later. And I am also going to explore some light and dark paintings of your garden from sketches I have made. Fingers crossed I am beginning to find a good seasonal rhythm for my work.

I’m also going to experiment more with photography, and explore the uses of light more and see where I can take it. As well as stillness I’m really interested in capturing the passing of time. For example the cyanotypes I made in your garden only needed a ten second exposure because the light is so strong there, whereas in my studio I need a fifty second exposure to create the same quality of image, but that longer exposure also captures that extended amount of time. I find that fascinating, and a route I’d like to explore. I also go to Westonbirt Arboretum in the winter, as there is always something out. Going there makes you realise how much there is to look at. There’s always something in season, or that has something in its branches to explore, and then you really are looking at winter. But I think your garden has a lot of winter interest, which I am looking forward to.

I also want to focus on the work without the pressure of a show, and just have a process for a while and see where things go, like the exhibition at the Garden Museum, who you introduced me to, and which came about very organically. I would like to be a bit more relaxed and take more time.

Do you have any burning ambitions for projects ?

I would love to be commissioned to create a stained glass window in a church. I’m not religious, but because I work so much with light, I could really see my work translating into stained glass effectively, with sun streaming through. I’d love to work with a craftsperson to do that. And I’d really love to create a design for the Chelsea Flower Show poster, which has always been something I’ve wanted to do. And I would love to do a residency in Japan.

Lucy’s work is available to buy from a catalogue on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs of Lucy and studio: Huw Morgan. All others courtesy Lucy Augé.

Published 25 August 2018

Previous

Previous

Next

Next