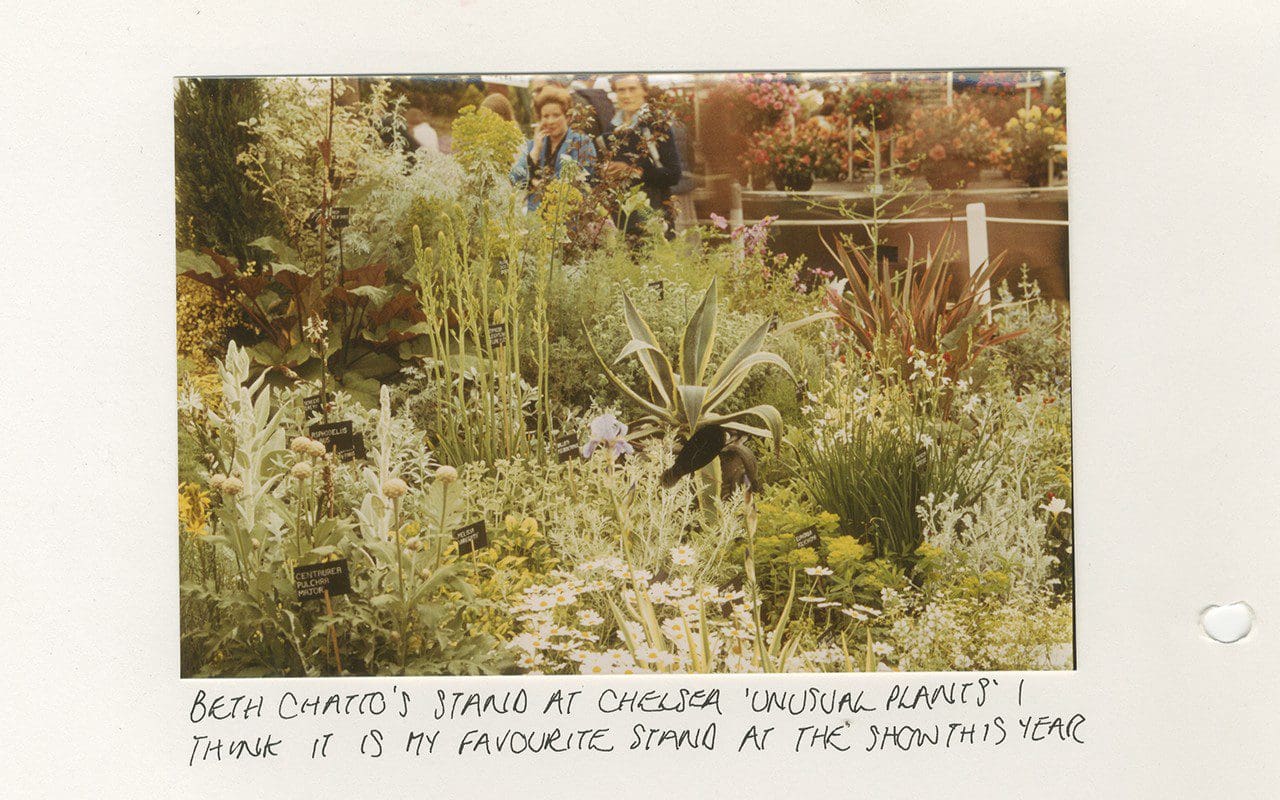

I first encountered Beth Chatto in 1977 at The Chelsea Flower Show. It was the first time she had exhibited and, aged 13, it was also the first time I’d attended the show. I remember quite distinctly the spell that was cast when my father and I came upon her stand. The froth, confection and sheer horticultural bravado that made the show remarkable fell into the background, and suddenly everything was quietened as we stood there, entranced.

We worked the four sides of the display, noting the differences between the plants that were grouped according to their cultural requirements. Leafy woodlanders cooled the mood where they were mingled together, with barely a flower, in celebration of a green tapestry. Nearby, and separated by plants that allowed the horticultural transition, were the delicate blooms of the Cotswold verbascums, ascending through molinias and sun-loving salvias. Plants with none of the pomp of the neighbouring soaring delphiniums, but which were captivating for their modesty and feeling of rightness in combination. The exhibit stood apart and was confidently delicate. We learned from it, filling notebooks hungrily with sensible combinations, happy in the knowledge that the wild aesthetic we were drawn to was something attainable.

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

A page from Dan’s 1980 Wisley notebook

At that point no one else was doing what Beth was doing and, when I met Frances Mossman, who commissioned me to make my first garden five years later, it was those show stands that brought us together. We talked at length about Beth’s ethos, the excitement of combing her catalogues of beautifully penned descriptions and our resulting purchases.

Of Crambe maritima, she wrote, “Adds style and grandeur to the filigree grey and silver plants. Waving, sea-blue and waxen, the leaves alone can dominate the border edge, while the short stout stems carry generous heads of creamy-white flowers in early summer. The stems are delicious, blanched in early spring, served as a vegetable. 61 cm.”

While Gladiolus papilio is, “Strangely seductive in late summer and autumn. Above narrow, grey-green blade-shaped leaves stand tall stems carrying downcast heads. The slender buds and backs of petals are bruise-shades of green, cream and slate-purple. Inside creamy hearts shelter blue anthers while the lower lip petal is feathered and marked with an ‘eye’ in purple and greenish-yellow, like the wing of a butterfly. It increases freely. Needs warm well-drained soil. 91 cm.”

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima with Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’, Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ and Matthiola perenne ‘Alba’ in the gravel by the barns

Crambe maritima

Crambe maritima

We came to rely upon her nursery of then ‘unusual plants’; me with a long border I had planted in my parents’ garden, and Frances with her own first garden in Putney. Unusual Plants was the place we would go to help us make that first garden together and, when we started making the garden at Home Farm in 1987, it was Frances who wrote to Beth to tell her of her positive influence and of what we were doing there to make a garden without boundaries. Beth wrote back with careful responses and encouragement. Once I had got over my shyness, I too started to write and we struck up a friendship from which I will always draw inspiration and refer back to as pivotal in my own development.

Beth made an indelible impression with her words, wisdom and practical application of good horticulture. In this country she was arguably the link back to the beginnings of William Robinson’s naturalistic movement and an informality that drew inspiration from nature. Her writings were always dependable and combined the artistry of an accomplished planting designer with the fundamental practicality of someone who had seen how plants grew in the wild and knew how to grow them to best effect in combination in a garden.

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

The gravel garden at Home Farm in 1998. Planting included Verbascum chaixii ‘Album’, Nectaroscordum siculum, Glaucium flavum var. aurantiacum, Stipa tenuissima, Limonium platyphyllum and Eryngium giganteum, all from Beth Chatto Nursery. Photo: Nicola Browne

If you study Chelsea today, it is easy to overlook the influence she had on the industry of nurserymen and designers. The ‘unusual plants’ that were her palette are no longer so, and the way in which they were combined naturalistically on her stands has become the status quo. Rare now are the perfect bolts of upright lupins and highly-bred, colourful perennials, not so the mingled informality of plants that are closely allied to the native species, many of which had their origins at her nursery.

Though we will all miss her presence after her sad departure last weekend, her influence will remain strong. In the hands of Beth’s trusted team, led by Garden and Nursery Director, Dave Ward and Head Gardener, Åsa Gregers-Warg, the gardens and nursery have never been better. In recent years, as Beth’s health has deteriorated, Julia Boulton, her granddaughter, has firmly taken the reins and, as well as ensuring that the gardens and nursery continue into the future, has been responsible for setting up the Beth Chatto Education Trust and, this year, a naturalistic planting symposium in her name which takes place in August. At its heart the gardens will become a teaching centre, a living illustration of Beth’s passion for plants and her ecological approach to gardening.

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

‘Beth’s Poppy’ – Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum

Looking around my garden this morning, I can see Beth’s influence almost everywhere in the plants that are grouped according to their cultural requirements. Be it the ‘pioneers’ in the ditch, which have to battle with the natives, or the colonies of self-seeders I’ve set loose in the rubble by the barns, her teachings and plant choices are everywhere. Her plants also connect me to a wider gardening fraternity, a reminder of her generosity and willingness to share. The Papaver dubium ssp. lecoquii var. albiflorum that has seeded itself around the vegetable garden was first given to me by Fergus Garrett as ‘Beth’s Poppy’, since she had passed on the seed, while the Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’ growing against the breezeblock wall by our barns, was collected by her great friend, the artist and aesthete, who helped open her eyes to the beauty of plants.

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Ferula tingitana ‘Cedric Morris’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’

A visit to the nursery is still one of my favourite outings. I can guarantee quality and know that I will find something that I have just seen growing right there in the garden and have yet to try for myself. About twelve years ago, on a trip that culminated in a full notebook and an equally full trolley, Beth gave me a plant of Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’ accompanied with the usual words of good advice about its cultivation. Sure enough, it is a good plant both in its ability to perform and in terms of its elegance. I moved it carefully from the garden in Peckham and divided it the autumn before last to step out in an informal grouping in the new garden. Last Sunday, although I did not know that this was the day she would finally leave us, the first flower of the season opened. As is the way with a plant that has a heritage, I spent a little time with her, pondering aesthetics and practicalities. I know for certain that it will not be my last conversation with Beth.

Beth Chatto 27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

27 June 1923 – 13 May 2018

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 May 2018

Previous

Previous

Next

Next