The houses in the valley sit on the spring line and in turn the ditches that run alongside every downward moving hedgerow each channel the spring water to the stream that runs below us. We are lucky to have water here, but it is always on the move, descending, passing through and never still. The silvery lines that trace the creases in the winter are all but eclipsed by foliage in the growing season, but we are aware of it always, sounding when the stream is in spate from way below us and babbling in the ditch that lies in the fold of land beyond the garden.

Making a still body of water has always been something we have planned for and over our time here we have found the place for it in the hollow, where the water might collect and you could imagine a stillness beyond the garden. A place where the flow is interrupted and paused before it continues its journey. Somewhere for the sky to come to earth and for reflections to be held and the world quietly magnified.

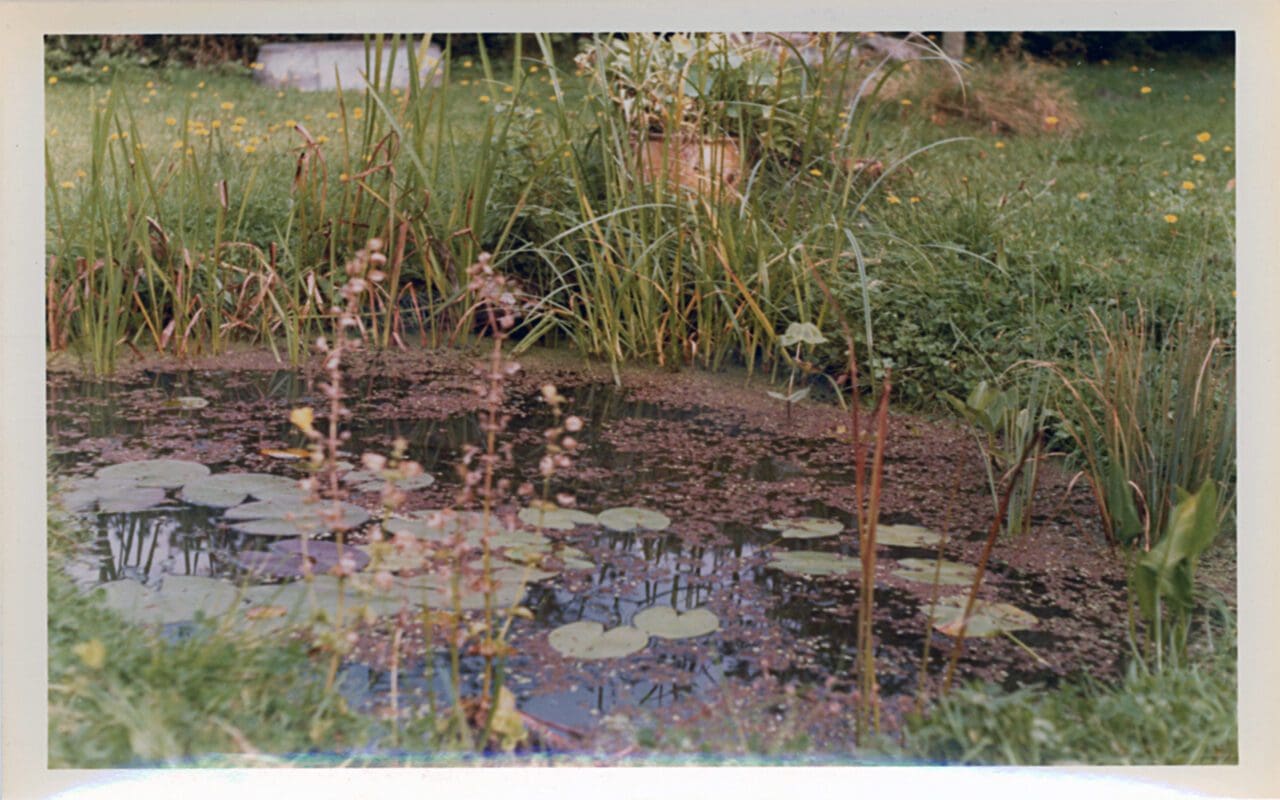

My father made a pond when I was about five and it was lying on the turf banks with my face hovering over the watery lens that I first encountered alchemy. The coming to life from a handful of raw materials and the energy of transformation. It was about five feet by four with a marginal shelf on three sides and the turf of the surrounding orchard folded over the edges to hide the blue plastic liner. I remember the smell of the pond plants pressed into the mud and the clear water soon eclipsing them entirely as it became opaque and green and began its evolution. After a couple of weeks of peering into the gloom, the pond skaters and water boatmen arrived apparently from nowhere and the water suddenly cleared. The muddy-mintiness of the Mentha aquatica was soon travelling into the banks and, like a hand unfolding, the water lilies slipped over the surface with their perfect flatness. Looking underneath and the gelatinous eggs of pond snails we’d added were already proof that the pond was becoming a home.

I have made several ponds since and witnessed the heart they bring to a place, so this year we decided to act on our ambitions at Hillside. I worked up a measured drawing to test the levels, but we laid it out by eye on the day so that it responded to the place. Ponds should always be bigger than you might think because the marginal growth can diminish the scale of the clear water by as much as a third. A pond should also be deep enough to retain the cool temperatures you need to minimise evaporation and discourage algal bloom. We were aiming for two metres of depth, but we had to stay above the level of the stream that runs below the pond so we managed about 1.5 metres. Deep enough to swim on a hot day and we hope to keep the water stable and the balance in place for the ecology.

We wanted the pond to not only feel like a natural culmination of the hollow, but for it to also retain the water with a ‘natural’ liner. By digging a test pit three years ago we’d found the clay there was not consistent enough to puddle the pond. Puddling is an old process of breaking down the clay structure by driving animals over it to pummel the base so that it holds water, but in order for it to work you have to have clay without impurities. Our clay, we found, had gravel seams running through it that would make puddling impossible.

In sites where there has been the right access and clay nearby, I have imported clay to avoid using butyl liners, but it was impossible here with our narrow access and steep slopes so we opted to use a bentonite liner. This is a manufactured fabric that suspends dry bentonite clay particles within a geotextile sandwich which is laid out like a carpet over the base of the pond. When hydrated, the bentonite expands and seals to form a waterproof lining.

We had to wait for the weather to be dry enough to have a clear run at the excavations. The topsoil was stripped over the area of the excavation and moved up the hill where we will eventually extend the barn garden. The next layer of subsoil, which we found to be ‘clean’ and free of stones was put to one side so that it could be spread in a 300mm layer over the liner to protect it from damage. The excavations ran for longer than we’d hoped with our slopes and rain making access impossible for a few days in August, but the rough shape was in place within a fortnight. We made steeper sides into the water on the long sides to discourage marginal growth and open up views of the water, with shallow shelves about 300 mm below the water surface where marginal plants would be allowed to colonise at either end.

A trench was dug along the bottom of the pond for a land drain which will take away any spring water that might put pressure on the liner from beneath and then a layer of sand was spread over the pond base to cushion the liner and prevent any stones potentially puncturing the seal. The liner, which came on 4 metre wide rolls, was immensely heavy and took some manoeuvring with a fork-lift and four men to heave it into position. It was then folded into a trench around the perimeter to hold it in place. A spill, where the water runs over a depression in the margin, takes any excess water away in a little swale into the stream so that the course of the water is continued.

Over the years of watching the springs that run in the ditches by the hedges, it became clear that the spring that runs from underneath the old milking barn on the hill above would be enough to charge the pond. We used salvaged stone that I’ve been saving over the years to build a head wall on the rim of the pond from which the spring water would issue onto a splash stone. A simple stone chute channels the spring water into a depression in the splash stone which gives the water an acoustic value rather than it moving through silently. The puddle in the splash stone has quickly become a washing place for the birds.

To fill the pond once the groundworks were complete, we tapped the fast running flow in the ditch that runs to the other side of the pond. It filled over the course of three days, with reflections we’d previously only imagined being caught and held there; the roll of The Tump as you look up towards the east, glimpsed views of the buildings on the hill as you look west and, in reverse, the trees of the woods which are now caught in colour that we have only ever seen in shadows on the slopes.

If the pond could have been bigger we would have made it so, I know that already, but it sits well in the hollow with the banks that rise to cushion it. It is said that the defining factor between a pond and a lake is that a lake is big enough for a swan to land and take off. We imagine that this will be a pond and that feels right here, held in the land form and with nowhere else to go.

We will not stock the pond with fish, preferring to see what arrives on its own from the ditch water and the existing ecology nearby. I do not plan on planting the pond until the growing season opens again next year, as aquatics need to grow into a season to take a hold rather than sitting cold as the season wanes. The aquatics are important though and they will help to balance the ecology in the pond so, on the 4th of September, a week after the water brimmed and wicked the margins, I sowed the land that had been disturbed in the making to heal the scar. A marginal mix of wetland natives from Emorsgate Seeds and, where we know the ground will sit damper, the Cricklade North Meadow Mix (hopefully with Snake’s Head Fritillaries and Meadow Rue), from the SSSI water meadows near Cricklade.

Whilst I was sowing the seed and with my head in an entirely different future that morning, Huw took our beautiful dog Woody to the vet as he’d been under the weather in the days the pond was filling. Neither of us knew on that Saturday morning that he wouldn’t return and that he had had his allotted time, but within a week that seed was showing green and we’d had the magical visitation of a never-before-seen kingfisher. New, unstoppable life and an alchemy we are lucky enough to be part of and nurtured by.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 October 2021

Previous

Previous

Next

Next