The woods in the hollow below us have finally been stripped of foliage to reveal bare bones and the silver-grey of the lichens that outline their trunks and branches. The garden has also dimmed, the last of the asters finally over and the summer foliage withered. In this new incarnation we are left with something altogether different. A garden still standing, but bleached of colour as it moves into the first throes of winter.

Every week there are changes as the falling away reveals the skeletons that have the stamina to stand against the winter. The new transparency allows us to see to the ground now where the evergreen rosettes are already hunkered and providing new interest. Remarkable for the fact that they have been there in the shadows all this time and slowly building in strength are the Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’. It was a delight to discover that the first generation of self-sown seedling have found their niche, nestled under the Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ amongst the pulmonaria.

Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’

Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’

This dark-leaved honesty is a refined selection and more ornamental than most with its burnished, Ace of Hearts foliage. It is hard to describe the colour, which on close observation shimmers deepest purple over a base of bitter chocolate. Just discernible at the centre is a shading to dark forest green. I have not yet built up a mix of generations in this young colony because my original plants flowered and seeded last year, but in time we will have enough plants for the satiny coins of seedheads to shine against this inky background. For now though the rosettes will provide a good foil for a group of February-blooming yellow hellebores that are clumping nicely and the lunaria flower, when it comes in April, will be a strong contrast to the primrose of the Molly-the-witch peonies which are also part of this grouping. ‘Chedglow’ has a good dark flower which is a dusky mauve, not the bright purple of the more commonplace honesty.

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’

Up by the barns and far away so that ‘Chedglow’ does not cross-pollinate and lose its lustre, I have Lunaria annua ‘Corfu Blue’. Though most are biennial, this particular form of honesty is said to be perennial. I am not sure that it really is, with only the odd plant coming again for a second year of flower, but the best ones are always those that seeded the year before and have built up a decent rosette in readiness. My original plants, which came from Derry Watkins at Special Plants, have now seeded freely in the gravel. The flattened seedpods of lunaria are a magical thing as they develop, first green and then becoming pale and luminous like their namesake as they mature. The dark seed, also flattened, is suspended between three sheaths of papery tissue which silvers before buckling to drop its cargo in late summer. The remains of the honesty will be around for a while yet, capturing wintry light.

Baptisia ‘Dutch Chocolate’

Baptisia ‘Dutch Chocolate’

At the other end of the spectrum are the seedheads of baptisia, matt charcoal black when you see them suspended in a garden that is drained of chlorophyll. I have five or six different selections in the garden now, which are proving their worth both with their lupin-like flowers and good summer structure. In autumn each has its own habit, some colouring buttery yellow before the leaves fall, whilst others darken, the leaves metallic grey, like pewter and hanging on for quite some time before dropping. Here we have ‘Dutch Chocolate’, but ‘Caramel’ and ‘Starlite Prairieblues’ also produce a good seedheads.

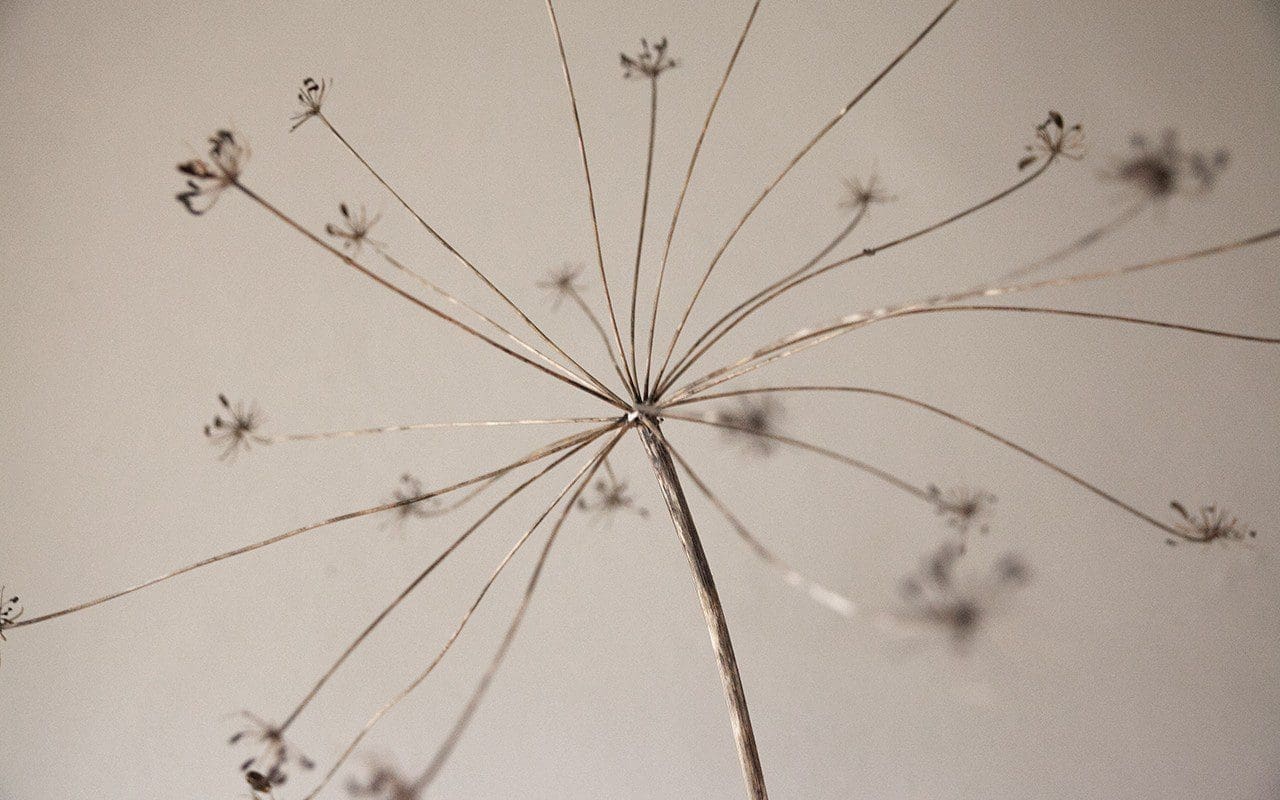

Laser trilobum

Laser trilobum

And finally, to give a feeling of the fragile remains in the garden this first week in December, are the spidery seedheads of Laser trilobum. This light-footed umbellifer moves away quickly from a glaucous leafy rosette in early summer to stand just over a metre high on wiry stems. The umbels can reach as much as 30cm across, so I give it plenty of room to hang loftily above low-growing Geranium macrorrhizum and white Viola cornuta. As an edge of woodlander it feels right amongst this cool greenery. Although it is reliably perennial, most of the seed has already dropped. It germinates easily in the right spot and, all being well, it will find its way into the planting on its own, to add the same dramatic delicacy of scale with its elegant, widely-spoked umbels, as it does here.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan Published 1 December 2018

The winter form of last season’s skeletons has been easily as interesting as the first summer in the new garden. Though their muted presence is not the thing you plan for first, it is an aspect that is worth considering for the ghosts that are left behind. Some, the daylilies for instance, leave nothing more than the space they took in their fleshy growth period, but those that endure are arguably as good as they were in life. Without the distraction of a growing season, its pull of colour and the steer of upkeep, you are free to look at the dead, left-behind forms anew. Blacks and browns, sepia, cinnamon and parchment whites are far from monochrome and their structures and seedheads are worth planning for in combination.

Snow flurries and rain laden winds began the topple in January, but the garden endured and weekly we have observed it falling away, shifting, dropping back and thinning. The vernonia, with their biscuit seedheads, stood tall amongst the pale spent verticals of panicum and I welcomed the repeat of the finely tapered Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ together with the bottle-brushes of Agastache ‘Blackadder’. The birds loved them too and some days the garden has been alive with activity with the foraging for seed and overwintering insects looking for shelter. The black stems of the veronicastrum were good amongst the molinia stems, but their seeds were stripped by mice early on. The grasses have been key for their foil, their pale colouring bright on dry days, warm in the wet, and their plumage acting as light catchers when the sun has broken through.

The clearance required to make way for the new season has been carefully judged. There comes a point, some time when the bulbs are showing you that new life is on its way, that the skeletons begin to feel tired. We have also had to pace ourselves, for it has taken five man days to work through the areas that were planted almost a year ago and, this time next year, it will take another three when the areas of the garden that were planted last autumn are grown up.

The lower bed before being cut back

The lower bed before being cut back

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

We made a start in early February, working from the high ground that drained most freely and sweeping round to the heavier low bed by the field in a second session a fortnight later. In just two weeks buds that had been thoroughly dormant were already showing at the base of the euphorbias and the first new shoots on the grasses signalled the shift and the need to move things forward.

Before we started, I waded into the beds and marked the plants that I knew I wanted to change, for there are always adjustments that need to be made in a new planting. The densely-flowered Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ will be exchanged for the more finely tapered L. virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’, while the Artemisia lactiflora ‘Elfenbein’ that read too strongly as a group once their pale flowers caught the eye were left standing so that I could find them again easily and redistribute them so that their presence is lighter this summer. The changes will be different every year, but it is good to have time in hand to make them whilst the plants are more or less dormant.

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

The feeling of working through and stripping away is always a mixed one. I would leave some plants standing for longer, indeed, I have with the liquorice and the fennel, but the spring clean is good. Underneath the tussocks of deschampsia we unearthed the nesting places of voles, which had already tunnelled out and made a winter feast of my inulas on the banks. We only found one, which scurried to safety and I was relieved to find that their damage hadn’t been greater. Last year when lifting the molinias from the stockbeds to split them in readiness for the new planting, I found them almost completely hollowed out, roots and crown all but gone under the protective thatch of winter cover. There are pros and cons to leaving the garden standing and, although I prefer to do so, it is a good feeling to see the clean sweep reveal the planting again in new nakedness. Tight clumps, indicating quite clearly now that they have broadened, how the combinations were set out on the spring solstice almost a year ago.

The dry, cut material was piled high on the compost heap where it will be topped by some of last year’s compost to help in rotting it back for the future. And at the end of the day, as light was dimming, we carefully raked between the plants so as not to disturb last year’s mulch. A couple of weeks later I combed through the beds again to winkle out any seedlings that we’d missed in the first pass. Dandelions already in evidence and ready to take hold in the crowns of the grasses and buttercups and nettles that been secretly travelling in shade under the cover of summer growth. The beds that were planted and mulched last year will only be topped up this year where they have been disturbed where I’ve made alterations. Hopefully growth will be sufficient to suppress all but the strongest of the interlopers. Although we are still waiting for the planting that went in during the autumn to show itself enough before mulching these new areas, it won’t be long now until the need to move will be upon us and the garden once again dictates the pace.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 February 2018

The Lenten Rose was one of my first infatuations as a child, rising like a phoenix from the leaf mould when little else was braving winter. We had discovered a solitary plant in a wooded clearing of our derelict garden and, though it was nothing special by today’s standards, it had survived the forty years of neglect that had finally overwhelmed the previous owner. I remember the excitement, the elegant outline of the hooded flower and lifting the plum and green reverse to reveal the boss of sheltered stamens.

In the years since, the excitement of their reappearance each February has never dimmed. In fact I depend upon them as their energy gathers and pushes against the last of the winter. Close observation over time has allowed me the opportunity of getting to know them better; the places they like to be, their surprising resilience and longevity and where to use them so that they offer you their very best. I have also developed a keen eye, winkling out the ones that have been superseded in terms of colour and form, so that I am only growing my absolute favourites.

Helleborus x hybridus Single Green Spotted

Helleborus x hybridus Single Green Spotted

Helleborus x hybridus Single Yellow Spotted Dark Nectaries

Helleborus x hybridus Single Yellow Spotted Dark Nectaries

I soon learned that it was important to hand select seed-raised Helleborus x hybridus since the variability is immense once they start to cross. Seedlings take about three to four years to flower if you are up for the gamble. The colours range from the darkest of slate-greys and plum purples through mauve and then on into a complexity of reds some of which err towards the pink end of the spectrum and others into apricot or the blush of ripe peaches. The yellows, perhaps the most prized due to their rarity, are a relatively recent development. The best hold a strong primrose for the duration of flower, whilst others fade to lime-green. The whites vary too, some clean, some limey, whilst others are infused palest pink. These base colours are sometimes overlaid with delicate veining or picotee edges of a darker tone, whilst the reverse may differ from the interior with a dusting of bloom or staining that gives away nothing of the world within. This is the stuff of obsession once you bend and cup a flower between your fingers to reveal a flash of another colour, a myriad spots or ink-dark nectaries.

An ark of hellebores came here with us from the Peckham garden. Planted on our south-facing slopes in the shade of a trial bed of shrubby willows, I expected them to struggle, but with summer shade they have loved the rich, deep ground and took some moving when they were relocated to their final positions the autumn before last. Moving Lenten Roses is easy if you do it in autumn, ahead of their period of main root activity. This is also the time to split your plants if you want to propagate a particular form, so that by the time they are pushing flowers they will have already found their feet.

The plants I brought with me were old favourites I have collected along the way. A purple as deep as damsons (main image), a slate-grey with bloom to the reverse and a particularly lovely green that has a freckling of burgundy spots within. I grew them all together in Peckham, the green lifting the darkness of the plum and a smattering of snowdrops to light them still further. I also have a fresh, clean white from Home Farm with green veins, and a creamy white picotee rimmed with deep red-violet and veined within. I parted with the dull reds and soft pinks once I’d visited Ashwood Nurseries and encountered the next level.

Helleborus x hybridus (Ashwood Evolution Group) Neon Shades

Helleborus x hybridus (Ashwood Evolution Group) Neon Shades

Helleborus x hybridus White Picotee Dark Nectaries

Helleborus x hybridus White Picotee Dark Nectaries

It was February, we had just had our offer accepted on Hillside, and the combination of winter weariness and the prospect of new ground inspired the journey to Ashwood. The nursery is famed for its hellebore selection programme and, within minutes of arriving, it was clear that these plants were far superior. The picotees were more finely drawn, pure whites overlaid with the merest lip of sugar pink, and there were pink and apricot picotees of even greater complexity. After several hours careful deliberation I came away with a number of yellows, selected for their dark plum nectaries, and some clean whites with the same interior stain. In the years since, I have added to the collection with green picotees, yellow spotteds and a number selected specifically for their veining.

As I do not have the luxury of shade, their favoured habitat, I have been winkling my collection in under shrubs or alongside tall, summer perennials that will throw them into cool when their foliage needs protection. Our slopes, however, are ideal for close observation and being able to look up into their blooms is a definite benefit. I have them grouped according to colour, the yellows and the whites alone and the greens and the darkest forms together. Under the medlar I have a collection of deep reds and warm-toned picotees to avoid the collection feeling too much like a sweet box and to allow me the opportunity of stumbling across something different as I move about the garden. Though I am not a fan of the doubles – they feel too cottagey here and too fussy in general – I do have one that is slate-grey which makes the flower very graphic and reminds me of a Louis Poulsen lamp. It has a place of its own under the wintersweet, where I can visit with a different mind-set.

Helleborus x hybridus Double Black

Helleborus x hybridus Double Black

Helleborus x hybridus Single Green Picotee Shades Dark Nectaries

Helleborus x hybridus Single Green Picotee Shades Dark Nectaries

The Lenten Roses are sometimes affected by a blackening on the foliage caused by hellebore leaf spot, which can be debilitating if it gets a hold. Best advice is to remove the foliage in the early winter and burn any affected leaves before the flower stems appear in January. I prefer to let plants settle in for a year or two before removing any foliage, but stripping them back does allow you to see the flower against a clean backdrop. Mulching after the leaves are removed also helps keep the plants moist, but basal rot can be a problem in damp years, so I prefer not to mulch right around the growth to keep the base airy.

For the first time this year, we have been plagued by mice which have stripped the buds of the earliest flowers and robbed me of this year’s respite from the last of the winter. The discovery left me fuming, but there are just enough to pick and float in water. The Lenten rose is not a good cut flower, but the stems are less prone to the flagging if you steep them for thirty seconds in boiling water. We prefer to float the flowers like boats in a shallow dish of water where you can savour their interiors and appreciate the gift they provide in these last few weeks of the season.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 10 February 2018

The hamamelis have burst their tight, velvety buds. Huddled darkly along bare branches, it is as if they have waited until we are hungry, our appetites pining for a break with winter. Welcome for the absence of life elsewhere, I fall under their spell again yearly, without fail and willingly. I first encountered them in maturity at Wisley, where in winter they were a mainstay of the winter plant idents, but it was not until my early twenties that I saw the true potential of the witch hazels. My friend Isabelle had taken me to Kalmthout Arboretum in Belgium to meet the owner, Jelena de Belder, the grower of many witch hazels and breeder of several of the best. The first, ‘Ruby Glow’ amongst them, were planted at the arboretum in the 1930s and the De Belders started their own breeding programme in the ’50’s. By the time we saw her collection in the early eighties, they were reaching out in maturity to touch one another, their fiery limbs, on a deep February winter’s day, an unforgettable understorey. The branches were bare and filled with the light of a million tiny filaments. The darkest as deep and red as rubies, and from there running through fire colours from the glow of smouldering embers to incandescent gold, flame yellow and palest sulphur. Writing now with a sprig of ‘Barmstedt Gold’ on the table in front of me, so that I can look in close detail, I remember further back to Geraldine’s Hamamelis mollis. Our neighbour, and my gardening mentor when I was a child, always picked a sprig to enliven her winter table. We would marvel at the strength of the perfume and its combination of delicacy and brazenness pitted against the odds of winter. So my witch hazel affair goes far back, but now is the first real opportunity I’ve had to put a shrub in open ground and be happy in the expectation of its future.

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’

Hamamelis mollis

Before here, in the Peckham garden, I grew hamamelis in pots, because there simply wasn’t space in the beds. They were surprisingly tolerant and it afforded me the opportunity of bringing them up close to the house in the winter to watch their buds unravel at close proximity. ‘Jelena’, a soft orange Hamamelis x intermedia hybrid named after Mme. de Belder, was always the first to flower, before Christmas in London and running through the length of January. It outgrew me, its limbs reaching wide and elegantly in a stretch that became harder and harder to accommodate when I moved it back into the semi-shade at the end of the garden. In the end I gave it away to Nigel Slater when creating a secret garden for him. A good home where I knew he would enjoy it, and every year I am delighted to see him post pictures of the first flowers on Instagram.

H. x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ (main image) and ‘Barmstedt Gold’, together with a plant of Hamamelis mollis, a gift from Geraldine, came with me from Peckham to here in pots. The intermedia hybrids produce the greater bulk of the coloured varieties but, though they are scented, not all have the pervasive scent of the straight H. mollis. It is often something you have to find and put your nose to, which is why it is worth placing them in a sheltered corner which will hold the perfume, or upwind of where you know you are going to pass. Growing most happily in open woodland, they are adaptable to being out in the open as long as their roots are kept cool and moist in the summer months, and will flower more heavily in the light. Scorched edges to the foliage will show you that they have been under stress and if, like me, you have no choice but to grow them in an open position, this can be alleviated with a summer mulch and long, deep watering when it gets dry.

The books will tell you that they prefer acid soil, but I have found them to be tolerant of alkaline conditions, as long as they have plenty of organic matter in the ground, do not dry out in summer nor lie wet in winter. However, what few books tell you is that they can be short-lived if they find themselves under stress. A tree of thirty years is doing well if you force them too far beyond their comfort zone. They are also slow to attain size, or feel slow because you have an image of wide-spreading limbs in your mind, not the stark twiggery of a young plant. In five to seven years you can begin to see the plant as you want it to be, but if you spend a little more than you’re comfortable with, seeking out a 10 or 15 litre plant that has some substance, the immediate payback is worth it. This year’s purchases – I find it very difficult to resist extending my experience of witch hazels – saw the instant benefits of a waist high ‘Aphrodite’ for nearly £40 and a twig of ‘Orange Peel’ for £15.

Hamamelis mollis

Before here, in the Peckham garden, I grew hamamelis in pots, because there simply wasn’t space in the beds. They were surprisingly tolerant and it afforded me the opportunity of bringing them up close to the house in the winter to watch their buds unravel at close proximity. ‘Jelena’, a soft orange Hamamelis x intermedia hybrid named after Mme. de Belder, was always the first to flower, before Christmas in London and running through the length of January. It outgrew me, its limbs reaching wide and elegantly in a stretch that became harder and harder to accommodate when I moved it back into the semi-shade at the end of the garden. In the end I gave it away to Nigel Slater when creating a secret garden for him. A good home where I knew he would enjoy it, and every year I am delighted to see him post pictures of the first flowers on Instagram.

H. x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ (main image) and ‘Barmstedt Gold’, together with a plant of Hamamelis mollis, a gift from Geraldine, came with me from Peckham to here in pots. The intermedia hybrids produce the greater bulk of the coloured varieties but, though they are scented, not all have the pervasive scent of the straight H. mollis. It is often something you have to find and put your nose to, which is why it is worth placing them in a sheltered corner which will hold the perfume, or upwind of where you know you are going to pass. Growing most happily in open woodland, they are adaptable to being out in the open as long as their roots are kept cool and moist in the summer months, and will flower more heavily in the light. Scorched edges to the foliage will show you that they have been under stress and if, like me, you have no choice but to grow them in an open position, this can be alleviated with a summer mulch and long, deep watering when it gets dry.

The books will tell you that they prefer acid soil, but I have found them to be tolerant of alkaline conditions, as long as they have plenty of organic matter in the ground, do not dry out in summer nor lie wet in winter. However, what few books tell you is that they can be short-lived if they find themselves under stress. A tree of thirty years is doing well if you force them too far beyond their comfort zone. They are also slow to attain size, or feel slow because you have an image of wide-spreading limbs in your mind, not the stark twiggery of a young plant. In five to seven years you can begin to see the plant as you want it to be, but if you spend a little more than you’re comfortable with, seeking out a 10 or 15 litre plant that has some substance, the immediate payback is worth it. This year’s purchases – I find it very difficult to resist extending my experience of witch hazels – saw the instant benefits of a waist high ‘Aphrodite’ for nearly £40 and a twig of ‘Orange Peel’ for £15.

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Aphrodite’

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Aphrodite’

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Diane’

Choosing the very best of a bewilderingly beautiful bunch is not easy, but my dabbling over the years has been worth it, for the named varieties have very differing habits. Being red-green colour blind, and losing some but not all reds, I must try hard to find ‘Diane’ when planted out in a garden. Up close I can see it is a wonderful colour and often use it for clients, but it is not one that I gravitate to for myself. It has a well-behaved, rounded habit and reliably scarlet autumn foliage, which singles it out as a variety to return to for two seasons of interest.

Several of the intermedia hybrids are problematic in my opinion for not losing leaves in winter, hanging on too long, like hornbeam or beech, to clutter what should be a naked stage of branches for the flowers. I have found that they do this in some gardens and not others and often they grow out of it as they mature, but I prefer the varieties that drop properly and most enjoy those that colour well in the autumn.

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Diane’

Choosing the very best of a bewilderingly beautiful bunch is not easy, but my dabbling over the years has been worth it, for the named varieties have very differing habits. Being red-green colour blind, and losing some but not all reds, I must try hard to find ‘Diane’ when planted out in a garden. Up close I can see it is a wonderful colour and often use it for clients, but it is not one that I gravitate to for myself. It has a well-behaved, rounded habit and reliably scarlet autumn foliage, which singles it out as a variety to return to for two seasons of interest.

Several of the intermedia hybrids are problematic in my opinion for not losing leaves in winter, hanging on too long, like hornbeam or beech, to clutter what should be a naked stage of branches for the flowers. I have found that they do this in some gardens and not others and often they grow out of it as they mature, but I prefer the varieties that drop properly and most enjoy those that colour well in the autumn.

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’

My plants here will be happy in our retentive loam despite the exposure, but I do mulch heavily with compost to emulate their natural wooded habitat. They have been planted here not only for the winter draw they provide, but also for the benefit of shade they bring to plants around them come summer. Rooting lightly and without heavy competition, they will provide home to spring flowering pulmonaria and erythronium which will come as they fade. The foliage of ‘Gingerbread’ has a copper flush as it comes into leaf, which is good with the Bath Asparagus planted beneath it, but later in the summer the branches provide a frame for Tropaeolum speciosum. The Flame Flower makes the branches flare again, when I have all but forgotten the winter spell that I am bewitched by today.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 January 2018

Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’

My plants here will be happy in our retentive loam despite the exposure, but I do mulch heavily with compost to emulate their natural wooded habitat. They have been planted here not only for the winter draw they provide, but also for the benefit of shade they bring to plants around them come summer. Rooting lightly and without heavy competition, they will provide home to spring flowering pulmonaria and erythronium which will come as they fade. The foliage of ‘Gingerbread’ has a copper flush as it comes into leaf, which is good with the Bath Asparagus planted beneath it, but later in the summer the branches provide a frame for Tropaeolum speciosum. The Flame Flower makes the branches flare again, when I have all but forgotten the winter spell that I am bewitched by today.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 January 2018 Late in December, and before I expected such a prompt return, the Cyclamen coum made their re-appearance. The tiny beaks of magenta broke bare earth, buds soon reflexing to flower, sturdy and gathering in number and oblivious, it seemed, to the winter. Of all the flowers that come in these darkest weeks Cyclamen coum seem to have the most stamina, flowering for what must be the best part of three months and, in that time, providing a continuity of hope. During their season, they will see the snowdrops in and out and be companion to witch hazel and wintersweet and be happy to be in the root zone where little else will grow.

The rooty places where the ground is already taken are where they prefer to be. Here they will spend their summer dormancy underground, their tubers kept cool but on the dry side and in perfect stasis. Come the autumn rains their season is activated and, without the competition of summer growth either above or around them, they are free to flower and build up a colony. Choosing the place where they can be allowed to reign is the secret and it has taken a while for me to find the perfect spot under the old hollies. The ground is steeply sloped here and the trees, with their high dense canopy and fibrous roots, make for strong competition.

Cyclamen coum

Cyclamen coum

Cyclamen are always best planted when in growth and not bought as dormant tubers, which have often been kept too dry for too long by the suppliers. Hailing as they do from the Caucasus, Turkey, the Lebanon and Israel Cyclamen coum prefer to be kept on the dry side when dormant, which is easier and less disruptive in a pot. The second advantage to planting when they are in growth is that you can hand-pick for best leaf variation and flower colour. The leaves are as variable as pebbles on a beach. Some, often sold as the ‘Pewter Group’, are almost completely silvered, others are green overlaid with silver, and others almost entirely bottle-green. The foliage, which is the size of a chocolate coin and held close to the ground, doesn’t like competition and you have to be careful not to team them with the leafier Cyclamen hederifolium which is more vigorous and will smother them or with other winter flowering bulbs such as Eranthis, which are prone to leafiness once they start to form seed.

A dozen plants were winkled in where I could find gaps between the holly roots last winter and top-dressed with a mix of gravel and bark to do no more than cover the tubers. I hand-picked my plants for the strong magenta forms, as I prefer the punch of their pure, bright colour to the softening influence of the paler pinks and white, which is what you more often see where they have naturalised. Last year’s plants have all returned with a clutch of seedlings held tight within their crowns. These miniature new plants look true to type (or more-of-less) in terms of leaf marking, but I will see in three years or so if the flowers are true to their magenta parents.

Various foliage colouration

Various foliage colouration

Seedlings have appeared in the crowns of last year’s plants

Seedlings have appeared in the crowns of last year’s plants

Tania Compton has raved to me about her Cyclamen coum naturalising best in pure gravel and I have hopes that mine will break free from their mound under the holly and venture into the sleeper steps that run alongside, their rubbly treads being the perfect habitat for them to run free. Cyclamen are prolific seeders if they decide they like you and a sweet coating on the seed makes them a delicacy for ants which will carry them quite some distance, so that they often appear in surprising and unexpected places. I have an image of the steps in a few years’ time being somewhere that you have to pick your way down in the winter as though on a glowing magenta runner, threadbare where our footfall influences where the cyclamen appear and where they don’t.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 January 2018

The hush and the breathing space that comes, now that the leaves are down and the grass has finally slowed, is palpable. In the mild spells between freezes I take this opportunity to square up the holding area by the barns. This is where one day I plan for a greenhouse, but for now it is where I propagate and look after the plants that are waiting for a home. The cold frames which reared the spring seedlings are now packed to the gunnels with plants that need protection from the lethal combination of winter wet and freeze. Auriculas and the Mediterranean herbs are kept on the dry side and the autumn seedlings and cuttings will make a surprising leap forward with this little extra shelter. Out in the open and hunkered together for protection are bulbs to go out in the spring, once I can see exactly where they need to be and that they are the correct varieties, as well as youngsters that are ready and waiting for areas that are not quite prepared in which to set them loose. This backlog is a perpetual conundrum, but I have a three-year rule so that the holding ground avoids becoming a corner of shame. If they cannot be found a place, they will be put out on the lane with a sign saying, “Please help yourself”. Very few are left unclaimed and I trust they find good and unplanned for new homes. One of the cold frames

One of the cold frames

Auriculas

Auriculas

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018

It took time after moving here to get used to the focal point of Freezing Hill. Scoring one of the few horizontals in a landscape that dips and sweeps and undulates, our horizon to the west is drawn more keenly for the line of trees that teeter on the ridge. A dark score mark perched between land and sky, which focusses the eye and draws you back.

We gaze upon them daily, several times a day, and always last thing before closing the house for the night. However, to start with I found the horizontal difficult, until it was grounded by the addition of the new footprint around the house. Our own landform of flatness, even the little we have, helps to make sense of it and the granite troughs echo the line and frame the land between and the sky above and beyond.

Last winter, the sixth we had been here, for the first time we walked the fields between us and there to bring our focal point into a new perspective. It was Christmas Day and, as we scaled the hill, the beeches reared up like giants above us. The air was still on the leeward slopes that protected us from the westerlies, but the roar of the wind coming from the valley beyond was in their branches. It was deafening where we stood in the beech mast at their feet and saw for the first time that they were pitched along the top of an earthwork* running along the ridge and now held in place by the clutch of their roots.

Over the year, drawn back to the shifting scene that they give focus to, we witness change. The transparency in their branches in the winter. A sometimes-near sometimes-farness, depending on the moisture in the air. The sweep of emerald field in spring. The piping line of ochre hay as the harvest is cut and then dried and bailed, the lines appearing and vanishing over the course of 48 hours in August. The line at its strongest on the chill, white days of frost and snow, when the trees and hedges score charcoal marks on the landscape. We see the sky differently for the anchor the trees provide between land and cloudscape over the course of the year. They act as a guide to the position of the setting sun, which dips far to their right in June and then, in a quickening progression as the summer slips, to their left and then so much further that you find it hard to imagine that it ever set behind them.

*Freezing Hill is the site of a Bronze Age earthwork and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

19 January | 13:34

19 January | 13:34

8 February | 17:12

8 February | 17:12

4 March | 17:18

4 March | 17:18

19 April | 19:53

19 April | 19:53

16 May | 20:30

16 May | 20:30

9 June | 01:10

9 June | 01:10

16 July | 20:40

16 July | 20:40

7 August | 20:34

7 August | 20:34

3 September | 18:32

3 September | 18:32

1 October | 18:08

1 October | 18:08

25 November | 15:57

25 November | 15:57

10 December | 16:14

10 December | 16:14

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 December 2017

Now that the garden is resting and the woods drop back into winter nakedness we are drawn out into the landscape. Mosses greener than ever, now that the winter wet is here again, lighting up the tree trunks brilliant emerald where sunshine slides through bare branches. The north side of the trunks colonised by the green algae, Pleurococcus, act as a woodland wayfinder and, on the eldest limbs and marking their age, the colonies of polypody are once again thrown into focus.

I am happy to see them now that it is winter and enjoy the primitive feeling the ferns bring to the woods and stream edges. Higher up on the slopes, where we garden almost exclusively in sunshine, is not the place they want to be. I have planted for shade but, until I have the cover, ferns will have to have their place out of the garden season and we in turn the opportunity to visit them where they choose to be.

Polydpodium vulgare

Polydpodium vulgare

There are three main species in the woods around us. Polypodium vulgare is perhaps the most adaptable, choosing in the main to live up in the branches, inhabiting the places where moisture is harboured. Clefts in branches, where the moss holds accumulated dampness, is where you will find them making home and, from there, they travel slowly outwards forming a matt of fibrous root that in turn collects the moss and the accumulated leaf mould so extending their reach.

Polydpodium vulgare

Polydpodium vulgare

The finest colonies sit on the topside of the oaks that, over the years, have leaned from the slopes to strike informal bridges across the streams. Running along their branches like feathered epaulettes, the polypody strikes an exotic mood that you might more usually associate with the epiphytic bush of New Zealand or cool temperate rainforest. They are an adaptable fern, shrivelling and browning in dry summer weather to return again with the autumn wet and remain evergreen throughout the dark months. I harvested a number of plants that arrived in the wood where we logged a fallen tree by the stream and have simply laid them down in one of the few shady places up by the barn, where they have taken root. I have plans to add them to the north side of the house where I will insert them into a wall close to where I keep the epimediums so that we can enjoy them at closer quarters.

A colony of Asplenium scolopendrium

A colony of Asplenium scolopendrium

Asplenium scolopendrium

Asplenium scolopendrium

The hart’s tongue fern (Asplenium scolopendrium) is one of the key plants you register on the ground in the winter woodland. Clinging to the steep banks of the ditches and streams where the soil is thinnest, they make fine colonies with mature plants almost touching, but not so much that you can’t appreciate their architecture. The simplicity of their foliage, each tongue arching elegantly downward, is a feature of limestone woodland and around here it is the most prevalent fern. The Victorian pteridoligists collected the hart’s tongue ferns with great fascination, naming and selecting the occasionally crested, fasciated and undulating variants. Several are still available today and are good in the winter garden for their long season of interest. The fronds last right through the winter to the point at which the new croziers unfurl in spring. You will know exactly when to cut them and refresh the plants, as the winter foliage begins to look tired with the contrast of spring around it.

Dryopteris filix-mas

Dryopteris filix-mas

The male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas) is less common here, where our soil lies heavy at the bottom of the slopes, but they do occur and I aim to introduce more when the hazel coppice matures. When I was a child, gardening in the thin, acidic woodland that faced the South Downs, Dryopteris filix-mas was a staple of the woodland and the clumps were many crowned, some as much as a metre across and aged. Where the polypody and the hart’s tongue last the winter, the male fern tends to brown and eventually collapse as the frosts work at the growth of the previous growing season. But they are beautiful in death and more so for the contrast of old and new as the dramatic unravelling of croziers happens in the spring. Brilliantly soft and scaled dark green over light, the fronds unfurl to reach waist height before filling out and relaxing for the summer.

A colony of Dryopteris filix-mas

A colony of Dryopteris filix-mas

Osmunda regalis, the royal fern, is the most spectacular of our native ferns rising up to shoulder height as the croziers reach and teeter before expanding lushly to lie back in a tropical splay of fronds. The royal fern is now rare in the wild due to pillaging by Victorian fern-lovers but, where it does occur naturally in parts of Ireland, you find it in wet, boggy ground or on the edges of ditches.

Whereas I have not been able to include the ferns as part of the palette in the exposed new garden, I have introduced the Osmunda around the new bridge at the end of the ditch. The plants have a horticultural edge, in that they are the dark form, Osmunda regalis ‘Purpurascens’. Though not as voluminous as the regular green form, this selection is notable for the extraordinary purplish-bronze colouring of the young croziers and the tint to the unfurling leaves. I have them in the delta of wet ground to either side of the zig-zag bridge as a companion to the ink-stained foliage of Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’.

Recently planted Osmunda regalis ‘Purpurascens’ around the new bridge in July

Recently planted Osmunda regalis ‘Purpurascens’ around the new bridge in July

New life appears in April from the knobbly knuckles that have been waiting out the winter in rafts of spongy root, once prized as a growing medium by orchid growers. It is a fast and marvellous ascent when the weather turns at the other side of the winter, the new growth the colour of Victoria plums and then copper as the fronds expand. At this point a daily vigil is necessary for there is not a moment to be missed. For now, however, I am happy for the wait that is made easier by their friends in the woods.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Seldom has anyone said, “I really fancy a turnip for dinner.” Along with their cousin the swede, turnips suffer from a longstanding reputation as being good only for animal fodder or the poverty-stricken.

The first reference to turnips (Brassica rapa ssp. rapa) is in John Gerard’s Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), where he writes, “It groweth in fields and diverse vineyards, or hoppe-gardens in most places in England. The bulbous or knobbed rotte, which is properly called rapum or turnip, and hath given the name to the plant, is many times eaten raw by the poor people, but most commonly boiled.” Over two hundred years later little appears to have changed when John Rogers states in The Vegetable Cultivator (1839), “That turnips are nourishing has been proved. In Wales, a few years since, they formed a considerable portion of the food of the lower classes’.

Even those doyennes of middle class Victorian cuisine, Eliza Acton and Mrs. Beeton, can suggest little more to do with turnips than boiling or mashing them. The most complicated treatment from both requires only a dressing of white cream sauce on the boiled roots. This addition of dairy produce in the form of milk, butter or cream provides the contrast to their slight bitterness – common to all brassicas – and which I imagine made them more acceptable to palates unatuned to this flavour. In oriental cooking, where bitter flavours are more highly prized, turnips are simply steamed or braised and cleanly flavoured with soy, mirin and fresh ginger. It is more common for them to be used raw as brined pickles or as a grated accompaniment, in the same manner as daikon, and they can replace these large radishes in all recipes that call for them, although their flavour is not as strong.

Turnip ‘Purple Top Milan’

Turnip ‘Purple Top Milan’

There are now a number of varieties available to grow, from the traditional purple top types through more decorative red and orange skinned varieties to the small, sweet, snow white cultivars from Japan. We rely on the commonly available ‘Purple Top Milan’, and successional sowing throughout the year from April to August provides us with a steady supply from late spring to early winter. Being fast growing and water lovers turnips do best in moisture retentive soil which has been enriched with manure for the previous crop. Early sowings are very prone to attack from flea beetle, which can decimate the young foliage, so these we protect with a layer of fleece or Enviromesh until the seedlings are large enough to fend for themselves. With a higher water content than swedes, turnips do not respond well to frost, so they should be lifted now and stored in sand or dry compost in a cool, dark shed for winter stores.

This recipe came from a desire to do something with our turnips that would give them the lead role in a main dish that would challenge people’s opinion – ours included – of this vegetable as a nothing more than a supporting player. With the current nip in the air as winter’s grip gets hold we are also increasingly drawn to spiced food, and a fresh curry is a great way to warm up after a day in the garden. Ample use of mustard seeds keep things in the brassica family, while coconut milk provides the contrasting equivalent of dairy. Unsurprisingly this recipe works just as well with swede, or any of the more commonly available root vegetables such as beetroot, parsnip and celeriac, although you may want to adjust the seasoning to counteract the sweetness of these last three with the addition of some lemon or lime juice just before serving. The coconut chutney is by no means essential, but the extra effort involved is minimal and helps turn this humble vegetable into a memorable main meal.

INGREDIENTS

Curry

800g turnip peeled and cut into 1cm dice

1 large onion, peeled and coarsely chopped

4 garlic cloves

4cm long piece fresh ginger, peeled

3 small green chillies, or more to taste

The stems of a small bunch of coriander

3 teaspoons brown mustard seeds

8 fresh curry leaves

½ teaspoon freshly grated turmeric, or ¼ teaspoon of powdered

2 teaspoons ground cumin

½ teaspoon ground fenugreek

2 small bay leaves

300ml coconut milk

400ml tomato passata

2 tablespoons red lentils

2 tablespoons rapeseed or sunflower oil

Salt

Chutney

150g fresh coconut, peeled, or unsweetened desiccated coconut

2 tablespoons chana dal

1 small green chili

2cm long piece fresh ginger

Salt

Temper

1 teaspoon urid dal

½ teaspoon brown mustard seed

½ teaspoon cumin seed

4 curry leaves

2 dried red chillies

A pinch of asafoetida

2 tablespoons rapeseed or sunflower oil

Serves 4 as a main or 6 as part of a mixed meal

METHOD

To make the curry first put the onion, garlic, ginger, chillies and coriander stalks into a small liquidiser (a Nutribullet type is ideal for this). Process into a paste. Scrape the sides of the bowl down several times to ensure a smooth consistency.

Heat the oil in a pan large enough to take all of the ingredients. When smoking add the mustard seeds and curry leaves and cook until the seeds begin to pop and the leaves are translucent.

Add the onion puree and cook over a high heat, stirring continuously, until the mixture has given up most of its water and is starting to become golden. About 5 minutes. Add the ground dried spices and the bay leaves and cook for another minute until fragrant. Add the tomato and stir well. Cook for another 3 minutes, stirring frequently.

Add the turnip to the pan. Stir well to coat all the pieces. Bring to the boil then turn the heat to low and simmer until tender. This will take about 20-25 minutes, but will be less for young turnips and maybe more for older ones. The turnips create quite a bit of liquid, but stir from time to time to ensure that it doesn’t catch.

Add the lentils and stir to incorporate. Continue to cook on a low heat for 15 minutes until the lentils soften.

Add the coconut milk and turn the heat back up to high. Boil until the lentils have disappeared into the sauce, and then reduce until there is enough to just coat the turnips. Season with salt. Keep warm.

Coconut Chutney

Coconut Chutney

While the curry is cooking make the coconut chutney. Heat one tablespoon of oil in a small frying pan. When smoking put in the chana dal and fry for a couple of minutes until toasted and dark orange in colour. Put the chana dal, coconut, green chilli and ginger into a small liquidiser and process until smooth. You may need to loosen the mixture with a few tablespoons of water or, if you have some coconut milk left from a 400ml can opened for the curry, some of that. Season with salt to taste.

To make the temper heat the remaining tablespoon of oil in the same small frying pan in which you cooked the chana dal. Add the urid dal and fry for a minute or two until golden, then add the remaining ingredients. Continue to cook until fragrant and the mustard seeds start to pop.

Mix half of the temper into the chutney. Transfer this to a serving bowl and then pour the remaining temper on top.

Put the hot curry into a warmed serving dish. Garnish with a few fried curry leaves, some rings of finely sliced red chilli and a scattering of torn coriander leaves. Serve with boiled rice or sponge dosa. This also makes a very good filling for a crisp masala dosa.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 December 2017

Not long after moving here, Jane, our friend and neighbour, took us for a walk into the woods in a nearby valley to see the green hellebore. We pulled off the lane and set off on foot along a well-worn way up into the trees. The north-facing slope had an inherent chill that set it apart from our south-facing slopes and the tree trunks and every stationary object were marked with a sheath of emerald moss.

The track made its way up steeply into ancient coppice. Land too steep to farm and questionably accessible even for sheep. Fallen trunks from a previous age and splays of untended hazels marked the decades that the land had been left to go wild. At least wild in the way that nowhere is truly wild on our little island of managed land. I knew the woods, for we had been here before in summer to look at the fields of orchids that colonise the open grassland above, where the hill flattens out into fenced paddocks. The woods are not extensive, but large enough to have their own environment in this steep fold in the land.

Somewhere near the top of the hill, with the light from the field above us just visible through the tangle of limbs, we set off sideways onto the slopes. The angle was steep enough not to have to bend too far to steady yourself with your hands, but consequently required a firm foothold when inching along the contour. Deep into the trees we came upon our goal. Nestled in under the roots of ancient coppiced hazel and up and out with the very first catkins, the Helleborus viridis.

A wild colony of green hellebore in the local woods

A wild colony of green hellebore in the local woods

To find a plant growing in the wild where it has found it’s niche is to truly understand its habits and requirements. Dry descriptions of habitats and associations in books instantly give way to a greater knowledge, for you never forget when you see a plant looking right in its place. In the cool of the north-facing slope and shaded not only by the deciduous canopy above, but also by the bole of the hazel and its influence, the hellebore was at home. With no competition to speak of, protected by damp leaf mould and with its roots firmly holding in the limestone of the hill, it was king of its place. New foliage, soft and emerald green, splayed fingers of early life. The nodding flowers, concealing the stamens, held free of the ground foliage on arching stems. Viridis, meaning green, is the colour of all its parts; a welcome one at the end of a long winter and a sure sign that the season is ebbing.

Several weeks later I returned in search of seed. The woods were flushed with first leaf which darkened the slopes. Nettles, already fringing the woodland edge where the light penetrated alongside the path, were ready to sting. But deep where the hellebores were growing, they were still in glorious isolation with little more than a few celandine and wood anemone for company. The flowers were transformed, the lanterns replaced by a rosette of bladders which were just turning from green to brown. I cupped my hand underneath and tapped. A slick trickle of ebony seed settled into the crease of my palm.

Green hellebore – Helleborus viridis ssp. occidentalis

Green hellebore – Helleborus viridis ssp. occidentalis

The seed of plants in the family Ranunculaceae is famously short-lived so I sowed it on the same day it was harvested, covered with grit and put in a shady place out of harm’s way. Three seasons later, the following March, it germinated with some success. I kept it in the shade on the north side of the house to throw its first leaves without disturbance. A year later I had seedlings that were ready to pot up and a year after that, to plant out. Jane took a number of the seedlings to start a colony on the north-facing wooded slopes that run up from our shared boundary, the stream. I planted the banks on our side, where the tree canopy provides the shelter, summer shade and leaf litter they need to do well. This year they are flowering for the first time in earnest and, with luck, will set seed and start spreading.

Though they were once used for their purgative qualities (as a folk remedy for worms and the topical treatment of warts), Gilbert White pointed to the fact that it is toxic in all its parts. ‘Where it killed not the patient, it would certainly kill the worms; but the worst of it is, it will sometimes kill both.’ With this in mind, I have kept it away from the sheep and have noted that, even down by the stream where the deer have their run, it remains completely untouched despite its lush, early growth.

One of the young seed grown green hellebores down by the stream

One of the young seed grown green hellebores down by the stream

Though rare in limestone woods in southern England, it is more common in parts of mainland Europe*. Cedric Morris found them in the Picos de Europa growing with a dark form of Erythronium dens-canis; a companion planting it would be hard to emulate here, because of the rush of growth that happens after snowmelt when everything comes at the same time. Its demure nature does not make it a match for the Lenten roses I have here in the garden, which feel rather opulent in comparison. However, I like it very much for its earliness, for its modest break with winter and particularly for the fact that it is native. Where my plants are establishing themselves amongst the newly emerging Arum italicum and an occasional primrose I find great excitement in the thought that spring is now unstoppable.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage