ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

Twenty six years ago I bought a newly published recipe book, which was to have a major impact on the way I cooked. It was the first River Café Cookbook. Throughout my university years I had been cooking from the books of Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson, Marcella Hazan, Richard Olney, Elisabeth Luard and Claudia Roden, but there was something strikingly different about Rose Gray and Ruthie Rogers’ approach to the Mediterranean kitchen.

Looking back, it is hard to imagine that their approach felt so new, so accustomed are we now to the ideas of seasonal eating and only using the best quality produce, but their minimal approach to preparation and presentation, so artfully expressed in the clean graphic design of the book itself, was not the norm and it was this simplicity of approach and insistence on the very best produce which still sets The River Café apart.

When I worked in film in the 1990s I was lucky enough to eat at The River Café on numerous occasions, my bill charged to various people’s expense accounts. Although it was, and still is, a glamorous destination the food was so memorable that after those heady days were over Dan and I would return whenever we wanted a meal to mark a special occasion; a fortieth birthday, a special friend visiting from overseas, a pre-marriage celebration, the purchase of Hillside. In the abstract, if you look at their menu, the food certainly looks expensive, but in all the years I have eaten there I have never once felt that the food is overpriced. The attention to detail in every aspect of the experience elevates it to a level that makes total sense of restaurant eating. If anyone ever comes to London and asks which is the best restaurant we can recommend I always answer, without hesitation, ‘The River Café’.

Several years ago, faced with this very question from Midori Shintani, head gardener at Tokachi Millennium Forest and an inveterate foodie, we booked ourselves a table. As the first plates were brought out I suddenly saw in the expression on Midori’s face that, although the ingredients may have been European and unusual to her, the care taken with the food was instantly comprehensible. Their restraint and reverence for seasonality and ingredients at their best and the honesty of presentation is comparable to that of domestic and commercial kitchens the length and breadth of Japan.

A favourite recipe from that first book, and one I have lost count of the number of times I have made, is for vignole, a Roman stew of fresh spring vegetables. Also known as vignarole, the vegetables traditionally used are artichokes, broad beans and peas. However, regardless of how good a spring we have or what countless restaurant kitchens would have you believe, these could never really be considered spring vegetables in Britain, so it is a dish I normally make in early summer. The vegetable garden got off to a very slow start this year and, although we have had artichokes for several weeks, it is only now that all three primary ingredients are cropping together. Given the lateness of the season we now also have the first Florence fennel, shallots, courgettes, bush beans and new season garlic, so this dish, based on the method used for vignole, uses everything that is at its best in the vegetable garden right now.

Recipes like this are infinitely adaptable. The only thing to remember is to add the vegetables to the pan in the order of those requiring the longest cooking first. Quartered baby turnips, carrots or the tiniest new potatoes near the start of the cooking time. Earlier in the season, asparagus spears make a fine addition. Add them at the same time as the broad beans. Young chard leaves or spinach can be added at the last minute or tiny radishes. Although mint is the customary herb to use for vignole, at this point in the year I like to combine it with basil which is growing in profusion in the polytunnel, the aniseed flavour of which complements the fennel well.

Serve warm to allow full appreciation of the different flavours and textures, this can be eaten alone as a starter with grilled bruschetta, accompanied perhaps with a melting burrata or fresh mozzarella or to accompany a piece of firm white fish such as halibut.

10 small artichokes with stalks

400g of peas in their pods or a mixture of peas and mange tout – 150g shelled weight

400g broad beans in their pods – 150g shelled weight

150g fine French beans

4 banana shallots – around 300g

4 baby Florence fennel – around 125g

3 small courgettes with flowers – around 250g

2 Little Gem lettuces

2 fat cloves of new season garlic

A small glass of dry white wine, water or stock – about 120ml

A small bunch of Genovese basil

A small bunch of fresh garden mint

The juice of two lemons

Serves 4 to 6

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Cook the whole artichokes for 5 minutes. Drain and allow to cool.

Shell the peas and broad beans and put in a bowl.

Cut off the stalk ends of the French beans.

Remove the roots, outer leaves, stems and foliage from the Florence fennel. Cut lengthways into eighths.

Peel the shallots and trim off the roots, retaining enough at the base, however, to hold the pieces together when cut lengthways into eighths.

Peel and finely chop the garlic.

Remove the flowers from the courgettes and retain. Cut off the top and bottom of the courgette. With the courgette lying horizontally on the chopping board cut off a diagonal piece from left to right. Roll the courgette a quarter turn away from you and make the same diagonal cut again. Keep turning and cutting until you have wedge shaped pieces of comparable size.

Remove the outer leaves from the lettuces until you are left with the hearts. Keep the leaves for a salad. Trim off any thick stalk, then cut the hearts lengthways into eighths.

In a heavy bottomed large pan gently heat the olive oil over a low heat.

Make a cartouche from a piece of dampened greaseproof paper large enough to cover the inside of the pan.

Add the shallot and garlic to the pan. Stir to coat with the oil. Lay the cartouche over the top, tucking it in to the sides so that no steam escapes. Put the lid on the pan and leave to cook on the lowest possible heat for about 10 minutes until the shallots are translucent and lightly coloured.

Remove the cartouche. Add the fennel and stir. Replace the cartouche and lid and cook for another 3 minutes

While the shallots and fennel are cooking remove the outer leaves from the artichokes and scrape any fibres from the stalk with the edge of a knife. Cut the spiny tops from the inner leaves. Cut the artichokes in half, remove the chokes with a teaspoon and then drop the hearts into a bowl of water to which you have added the juice of one lemon. When they are all done remove them from the water with a slotted spoon and add to the pan of shallots and fennel with the courgettes and French beans. Stir gently. Pour over the glass of wine. Replace the cartouche and lid again and cook for a further 3 minutes.

Lay the lettuce hearts on top of the other vegetables, add the broad beans and peas, replace the cartouche and lid and cook for another 3 minutes.

Remove the pan from the heat and allow to stand for 10 minutes to cool slightly. Then season with salt and lemon juice to taste. You can add some more olive oil now too if you like.

Coarsely chop the basil and mint. Remove the bases from the courgette flowers and discard. Slice the flowers lengthways into thin ribbons. Add all of these to the pan and stir everything together very gently so as not to break up the vegetables.

Leave to stand for another 5 minutes for the flavours to develop before serving.

Recipe and photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 17 July 2021

It was exactly a year ago, in the first week of lockdown, that we committed to buying a polytunnel. That same week I placed a very late seed order primarily for tomatoes, but some chillis, aubergines and cucumbers came too and we started them off indoors at the end of March. This late start was further compounded by the delayed arrival of the polytunnel itself, so that the seedlings intended for it had to be held back by hardening them off in a makeshift structure of seed trays and pieces of glass, since the cold frames were full. Although they got a little leggy and had to be watched carefully to ensure their 9cm pots did not dry out, they escaped the very late frost we had on May 12th and were finally planted into their grow bags in the first week of June.

This year I sowed the tender veg a full month earlier in late February, starting them off on the airing rack above the kitchen range before moving them to a warm windowsill as soon as they started to germinate. We are always keen to try new varieties and this year, alongside our old favourites ‘Gardener’s Delight’ and ‘Sungold’, I made a selection from Real Seeds based on productivity and hardiness, and also a range from very earlies to lates to see if we can stretch the season and push the tomato harvest into early winter. ‘Amish Paste’ is a heavy-cropping, extra-large preserving tomato, which I am trying instead of ‘San Marzano’, ‘Feo di Rio Gordo’, a deeply ribbed Spanish beefsteak variety that is reputedly very early for its size, while two Ukrainian varieties, ‘Purple Ukraine’ and the peach-fleshed ‘Lotos’, have late seasons, the latter with a reputation as one of the latest-cropping tomatoes, with fruit still pickable in late December.

Last year’s aubergines suffered from not being planted out soon enough and failed in the frames so, determined to have a crop this year, we have three varieties on trial; ‘Black Beauty’, which has a reputation as the most reliable cropper in the UK climate, which it seemed to prove by being the first and most profligate to germinate and with the largest, heartiest seedlings. Germination of the other two varieties – ‘Tsakoniki’, a Greek heirloom variety and ‘Rotonda Bianca Sfumata di Rosa’, both from Thomas Etty – was a little patchier, but we have enough seedlings to have three plants of each and still have some left to give away to friends and neighbours.

As well as new chillis ‘Basque’ and ‘Chilhuacle Negro’ I have succeeded in germinating the seed of some tiny superheat red chilli bought at Kos market two summers ago and I’m trying sweet peppers for the first time (‘Kaibi Round No. 2’ and ‘Amanda Sweet Wax Pepper’, also from Real Seeds) as well as two varieties of melon (‘Petit Gris de Rennes’ and ‘Charentais’), which I’m hoping will get enough light and heat to provide us with something truly exotic in the fruit department this year. All of the above were sown in the last week of February and they are all, bar the melons, ready to be pricked out into larger pots this weekend.

The delay in planting out last year had a continuing knock-on effect, and the last of the tomatoes were harvested in late October so that we could remove the grow bags (which were were last year’s quick fix) to build four raised beds. These allowed us to build up the level and enrich the soil of the unimproved pasture on which the polytunnel is sited with well rotted manure. We intend to practice no dig with these beds and so the retaining edge will help to keep things tidy.

Although I had sown a variety of oriental greens, winter salads, chard, kale and soft herbs from the beginning of September and into October and November it soon became apparent that this was also too late since, by the time the raised beds were finished in early November, the days had shortened to the point that none of the seedlings would make no further growth before the end of the year. These plug plants sat rather reproachfully in the cold polytunnel until late January, when I finally planted them out as the days slowly started to lengthen. However, they have now been providing us with salad and greens for two weeks or more and have more parsley, coriander and dill than we know what to do with.

Despite the late start what has become immediately apparent is that, with well-timed sowing and transplanting, the polytunnel will allow us to close the ‘hungry gap’ of late winter and early spring. In addition to salad and oriental greens there has been a seamless handover from the waning kale and turnip greens in the kitchen garden to those that were sown in plugs in late November and have now taken up the baton. With this knowledge I am now planning two late summer sowings of winter greens and salads, turnips and beets for late July and late August to take us through the season. I started my first salad, beetroot and kohl rabi sowings off in the tunnel this year and they have responded well to the warmth and even light, but we are also planning to build a hotbed in the polytunnel this winter so that we can get even further ahead with early sowings and keep our most tender seedlings warm at night.

Alongside planning for future winter crops this is now the time to get moving outside. The broad beans that I sowed in modules in early March in the polytunnel have been hardened off for a couple of days this week, ready to be planted outside. And it is potato and onion weekend. The potatoes have been chitting in egg trays in the tool shed for the past three weeks or so and will be going into newly dug ground that we have enclosed around the polytunnel. This will free up more space in the kitchen garden to get a better successional rotation going, as well as allowing us to extend the range of vegetables we can grow, like Jerusalem artichokes which are very space hungry and freezer harvest crops like the ‘Cupidon’ beans of which we can eat any amount.

And I will also be pricking out the tomatoes, which is where this all started. Holding them carefully by their first cotyledons I will extricate their roots from one another, acutely aware of the time, energy and care that has got them this far. I will move slowly and carefully so that none are wasted. I will lower them into the soil of their own pots, give them a drink and then leave them to get on with it until it is their time to take the stage again.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 March 2021

We’ve never had much luck with cauliflowers. With a reputation for being tricky customers, sensitive as they are to inconsistency during the growing cycle, they also generally require a very long growing season, thus making inconsistencies in cultivation far more likely. As the queen of vegetable growing, Joy Larkcom, succinctly states in our kitchen garden bible, Grow Your Own Vegetables, ‘The secret of success is steady growth, with plenty of moisture both at young plant stage and when maturing. Growth checks are caused by delayed transplanting, or spells of drought, resulting in deformed and small curds.’ Having had some unexpected success with the purple-headed ‘Sicilia Violetta’ two years ago, last year I was determined to break our dissatisfactory run once and for all and grow a harvest we could be proud of.

I had picked out two varieties, both from Real Seeds, ‘All The Year Round’ and ‘Autumn Giant’. The first because it promised the ease of successional sowings, and the second since it was reportedly ‘very reliable’. Both were sown in plugs on April 12th and were ready to plant out five weeks later in the middle of May. I looked after the young plants assiduously, watering them regularly and giving them a fortnightly liquid manure feed from mid-June as the plants started to grow away in earnest. Whether the feeding initiated it or not I can not be sure, but by early July it was apparent that all eight plants of ‘All The Year Round’ were on target to produce huge and beautiful, snow-white curds that would all be ready to harvest simultaneously in a matter of days. It was equally apparent that there was no way Dan and I were going to be able to eat all of them ourselves in the time available.

I chose my day carefully, reorganised the freezer, cleared the decks in the outside kitchen and assembled the equipment required for a mammoth batch of blanching. Cauliflower plants are huge, and it took some sawing and wrestling to take them all down, but eventually my catch was landed and Dan took my picture standing over them, inordinately proud. A large pasta pan with a colander insert makes blanching an easy affair, and as each batch went in I would set the timer for 3 minutes and return to preparing the next in line, removing the leaves and slicing each floret in two. Despite my apprehension of a neverending mountain of caulis the whole process of harvesting, preparing, blanching and bagging up seven of them for the freezer took around three hours. This really doesn’t seem a bad investment for the number of prep free meals they have provided this winter.

Dan posted his pictures of me on Instagram and that evening I got a message from Errol Fernandes. Errol is a Senior Gardener at Kenwood House in Hampstead and through his connection to Great Dixter we have come to know each other a little on social media, but have never met. Errol directed me to a post of his which gave his own recipe for blackened cauliflower inspired by his Goan mum’s home cooking, in the hope it might help us get through our cauliflower glut.

Knowing that we live in deepest, darkest Somerset Errol offered to send me some of the harder to come by ingredients – namely the back salt, powdered lime and mango powder. I have used dried lime and mango powder before, but never the black salt. Errol warned me, ‘It smells like bad eggs, but don’t be put off! It’s essential for the dish.’ When the little cellophane packets with hand-written labels arrived a few days later the distinctive sulphurous smell instantly transported me back to the Diwana Bhel Poori House on Drummond Street behind Euston station. When I was living in Camden in my mid 20’s I used to eat there on a weekly basis with my friends Simon and John Paul. The crisp-shelled poori, served with potatoes and chick peas and an appetising chutney that I now understood was flavoured with black salt.

Black salt (also known as kala namak) comes from volcanic salt mines in the Himalaya, and has been used in Ayurvedic medicine for centuries for its cleansing, detoxifying and digestive properties. Its pungent smell acts in a similar way to asafoetida, adding a deep, hard-to-pin-down umami richness which makes it incredibly more-ish. The powdered dried lime, mango powder, lime juice and turmeric combine to produce a deliciously astringent flavour which makes this a perfect dish to greet the changing season and wake up our slumbering taste buds and livers.

Each time I have made this dish I have taken the little cellophane packets of black salt and lime powder that Errol sent out of the spice cupboard and each time I have been reminded of his kindness at that time. We had just come out of the first lockdown and everyone was feeling raw, apprehensive and yet keen to connect. As Errol wrote to me when I asked him if I could share this recipe today, ‘I love sharing my food/culture, and I love learning about other people’s. Food is a wonderful way of connecting…’ So, as we look forward, hopefully, to a summer of renewed connections, it makes me happy to be able to share that connection with you.

1 cauliflower (around 1kg)

1 tablespoon coriander seed

1 teaspoon mango powder

1 teaspoon lime powder

1 teaspoon black mustard seed

1 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon salt flakes

½ teaspoon cumin seed

¼ teaspoon garam masala

¼ teaspoon Kashmiri chilli powder

¼ teaspoon asafoetida

¼ teaspoon Himalayan black salt

½ large green chilli, coarsely chopped

1 large clove garlic, coarsely chopped

8 curry leaves

Juice of half a lime

2 teaspoons cider vinegar

2 tablespoons rapeseed or other unflavoured oil

Separate the cauliflower into florets and cut these in half or in quarters depending on size. Cut the core and stalk a little more thinly. Include the young tender leaves too. You want bite size pieces that all will cook evenly. Put it all into a glass or ceramic bowl.

Put all of the other ingredients into a mortar and crush slowly and gently to make a coarse sauce. You want the garlic and chilli to be bruised and broken, but for the whole spices to mostly retain their form.

Spoon all but one tablespoon of the marinade over the cauliflower and mix thoroughly. I find it is quickest and most thorough to do this with your hands, but wear gloves if you don’t want the turmeric to turn your hands yellow! Cover and leave to marinade for at least an hour.

Pre-heat an overhead grill to hot. Arrange the cauliflower pieces in a single layer on a baking sheet and put under the grill for 20 to 25 minutes. Turn the pieces every now and then until all are cooked and charred in places.

Spoon the remaining marinade over the cauliflower with a squeeze more lime juice. Garnish with fresh coriander and more finely sliced green chilli and eat piping hot.

Serves 4 as a main side dish or 6 as part of a mixed plate meal.

Recipe: Errol Fernandes | Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 February 2021

With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

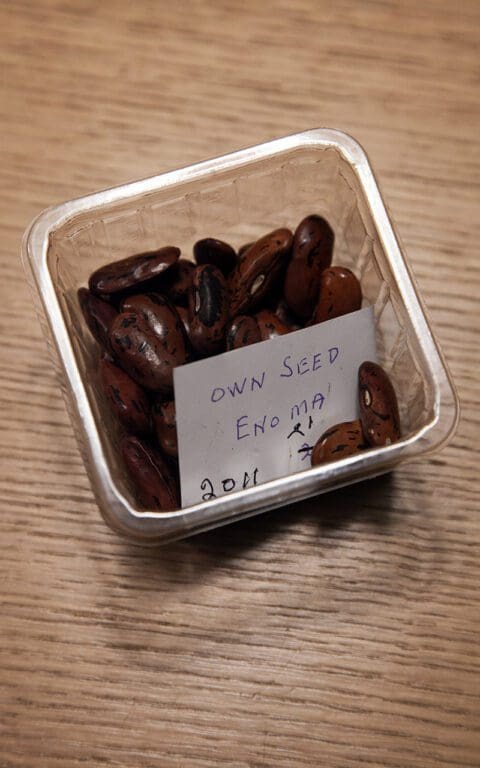

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

One of the benefits of working from home in Somerset this year is the time we have gained to harvest. Previously, there has always been a disheartening moment in late summer when it becomes apparent that there simply aren’t enough hours to get everything in the kitchen garden gathered, processed and stored away for winter. In the past, to dispel the phantom of wastage, we have managed this in a number of ways. Firstly, by inviting friends down for harvesting and preserving weekends – which has clearly not been possible this year – giving away the surplus to neighbours or leaving it out for passers-by or, finally, satisfying ourselves with the knowledge that what we can’t eat will be gladly seized upon by birds, rodents, insects and gastropods.

Though we blanched and froze enough French beans, broad beans and cauliflower to provide for us through the winter, it quickly became apparent that our harvest of soft and stone fruit would soon fill both freezers. Knowing that when everything else started to come on stream the question of what to do with it all would present itself, I prepared myself by reading Piers Warren’s How to Store Your Garden Produce and its American equivalent, Keeping the Harvest by Nancy Chioffi and Gretchen Mead. Both books give detailed instructions on how to freeze, salt, dry, bottle, ferment, pickle and preserve any fruit or vegetable you care to name.

My primary concern was for the tomatoes, of which we had a lot and of which I was determined to ensure not a single one was wasted. The idea of having our own supply of tinned tomatoes and passata – some of the few things I still buy from a grocer or supermarket – led to a frenzy of bottling in August, and the pantry shelves soon groaned with jars of whole and chopped plum tomatoes and bottles of passata. In Italy what I produced would strictly be called tomato sauce, as I learned that true passata is actually raw, with whole tomatoes being put through a passa pomodoro (tomato mill) that separates the skin and seeds from the pulp. The raw pulp is then put into sterilised bottles, the only cooking being from the time spent in the sterilising water bath required to preserve them.

I cooked the tomatoes and simmered them until there was no excess water content before passing through a mouli-légumes and then bottling with a dash of salt and citric acid to aid preservation. A late summer glut of cherry tomatoes resulted in a further 5 kilos of bottled, whole tomatoes, as well as several litres of yellow tomato ketchup, made using an adapted recipe from Kylee Newton’s The Modern Preserver.

In anticipation of this year’s bumper harvests, in May I had decided to invest in a dehydrator. When I could see that space in the pantry was soon going to run short it came into its own. For several weeks in late August and September it saw an almost permanent relay of pears, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries, but mostly many kilos of tomatoes. The benefit of drying, of course, is that the resulting produce takes up less space. It is also much lighter to store and concentrates the flavour, so a little goes much further when you come to cook with them. Most of the dried tomatoes are stored in an airtight bucket with a lid, but I have also preserved some under oil with bay, thyme and garlic cloves, to eat as savoury snacks or used to enrich other dishes.

The last of the tomato preserves came about more from necessity than design. I was completely out of shelf space in the pantry and yet there were still kilos coming up from the polytunnel. So, having gone through the same initial process as for the ‘passata’, the resulting sauce was reduced over a low heat until thick enough to spread out on greaseproof paper and put into the dehydrator. By the end of the next day I had enough small jars of tomato concentrate to see me through a winter of casseroles, soups and sauces.

It was just last weekend that we harvested the very last of the tomatoes from which we made about 5 litres of tomato soup. Given heat by the addition of some chilis also grown under cover this year, it warmed us through a whole week of sunny but chilly outdoor lunches. The thing that really makes me glow, though, is the prospect of opening a jar of my own plum tomatoes in January or February and bringing a memory of summer’s richness to the depth of winter.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 November 2020

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage