Three years ago, Troy Scott-Smith invited me to become a Garden Advisor for the garden at Sissinghurst. It was a role I was happy to explore, for I have known the garden for years as a visitor, but there is nothing like getting to know a place better from behind the scenes and through the people that work there.

Anyone who owns or gardens a garden knows all too well that feeling of only seeing what needs doing. Sometimes it is hard to focus on the achievements, the long view or to simply take stock and see what is happening in the here and now. My annual meetings with Troy take place in a different season every year, with notebooks and an open brief to walk and talk and ponder. This year I made my visit in late March, a good time to evaluate a garden while the structure is still visible.

A second eye from an outsider is often exactly what is needed and we have cultivated an openness in the discussion, where opinions may count here but not there, and where the shared mission is to get to the essence of things. For me, this is a complete luxury, as I am free of the responsibility I have in my role in the design studio and can look without having to provide more than an honest opinion.

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

By way of introduction Troy had sent me his manifesto before my first visit. When he applied for the role as Head Gardener he talked openly of the need for change and, to the credit of the National Trust, they employed him to implement this vision. He absolutely did not see this as change for change’s sake, but a means of recapturing the potent sense of place that Vita Sackville-West celebrated in her writing about the garden that she and Harold Nicolson had made at Sissinghurst Castle; a garden inextricably linked to the buildings it surrounded and, in turn, the Kentish farmland and countryside that swept up to its walls.

Troy saw the need for the place to be unlocked again from the rigour that had become the way that people came to know the garden after the death of Vita and Harold in the 1960’s. A challenge perhaps for the most famous garden in the country but, for one with such good bones, a new era of excitement.

The Top Courtyard

The Top Courtyard

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

The White Garden

The White Garden

The Orchard

The Orchard

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

I expect that there are very few good gardens that are the product of one vision. Gardens are places where skills come together and, indeed, where they work in combination to make the whole altogether stronger. Vita and Harold’s relationship was a perfect example. He with his architectural mind providing the structure and she, the romantic, the counterpoint of informality. Her writings talk of a place that was, first and foremost, lived in by its owners and where ideas and experiments did not demand year-round perfection. However, the garden then did not have the pressures it has now with up to 200,000 visitors a year. Mulleins breaking into the paths could be negotiated and roses reaching beyond their allocated space were free to reign.

Vita wrote well about her gardening experiences and possessed a powerful vision, but she was not a professional gardener. She was learning as she evolved the garden and, like all of us, her mistakes and failures were probably as numerous as her successes. Clambering roses overwhelmed the apple trees to bring them down where their vigour wasn’t matched, and some areas of the garden were simply allowed to recede into the background when out of season. There were bold and visionary moves, such as the tapestry of polyanthus in the Nuttery that would ultimately fail to disease and need rethinking.

When the National Trust took over in 1967, five year’s after Vita’s death, an inevitable tightening up eventually saw the garden reach extraordinary horticultural heights in the hands of Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger who worked with Vita from 1959 until she died, but went on to make the garden their own during their 30 year tenure as joint head gardeners. Pam and Sibylle’s prowess with plants was a large part of what brought visitors to Sissinghurst in their droves in the 1970’s and ’80’s, securing its place as one of the most influential gardens in the world. The way the garden became was ultimately driven by the need to provide for increasing numbers of visitors and, in so doing, the intimate sense of place was slowly and gradually altered.

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

In the Rose Garden

In the Rose Garden

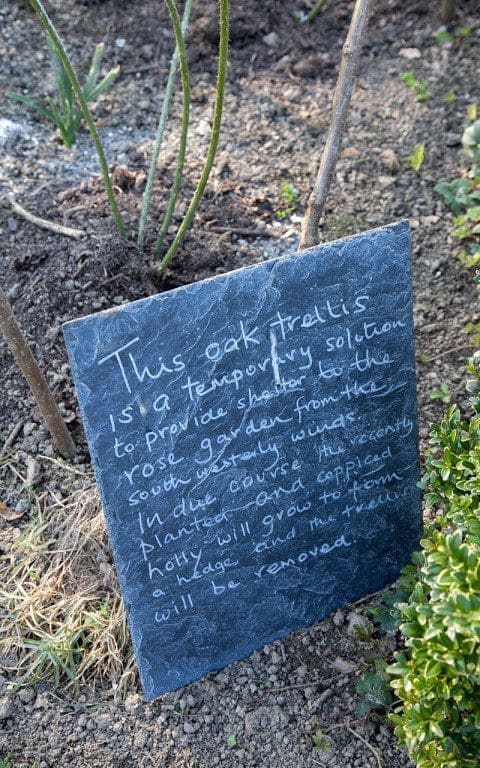

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

I have known Sissinghurst since I was a child. My father and I would visit every summer and walk its enclosures with notebooks in hand. I remember very distinctly the feeling of awe and then panic fused with disappointment that we would simply never be able to garden to this level of perfection. So we would drive on determinedly to Great Dixter to take the antidote of a garden living and breathing its owner and not attempting to garden with belt and braces. Even when the blueprint is strong gardens can easily assume a different character, for a garden is really the gardener.

And now Troy is slowly and gently making changes. He has turned the lawns at the approach into meadow and reinstated an old cart pond. There is a new hoggin entrance and there is talk of returning some of the brick and stone paths in the gardens to grass. If they wear, people will be redirected until the grass recovers, to preserve the calm and intimacy of the softer surface.

Roses that were tightly trained against the walls were given a couple of years off to reach away from their constraints. New apple trees have replaced old and the cigar-shaped yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape, as they were in Vita’s day. The Little North Garden (formerly the Phlox Garden) was for years made inaccessible from the White Garden after the steps were removed in 1969. It has been reconnected with new steps which will provide another way out when the White Garden is at its peak and crowded. And Troy is planning on re-instating the phlox that once grew there in Vita’s time and after which she named it.

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

The White Garden. The Little North Garden is reached through the arch in the boundary wall.

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

For years the Kentish Weald was the driving force and counterpoint to the formality of the garden and its enclosures, so we have talked of taking pressure off the garden and of making it less introverted, opening it up again to the land around it. The Nuttery has been enlarged, with new coppice hazels, a softer secondary path and a permeable fence boundary to the fields beyond. By removing the later addition of the hedge along the Nuttery, the field and the lake it flanks instantly provide a visual decompression. There is now talk of allowing people into the meadow and down to the lake so that, when the garden is busy, it provides an overspill area. After many years without them, Troy is also planning to reinstate Vita’s massed plantings of polyanthus in some areas.

The Nuttery

The Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

Last year, Joshua Sparkes, one of the enthusiastic young gardeners working with Troy, won a scholarship to visit Delos, the inspiration for one of the garden areas that has lost its way. Vita and Harold had been inspired by the Greek island and had strewn the area beyond the Top Courtyard with a small number of artefacts and stone walls to conjure a Greek hillside. Facing north and with exposure to the winds from across the fields, the site was not the ideal place to try such an experiment.

Later incarnations saw the garden protected on the windward side with a hedge of Pemberton roses and a canopy of magnolias took over to provide more shade, which subsequently saw the garden become home to primarily woodland plants. However, Troy has a little grove of cork oaks waiting in the nursery and Joshua’s research has identified a number of Greek natives to bring out the spirit of the place again. It may not be exactly as Vita and Harold had intended, but they wouldn’t have stood still either. As gardeners I have the feeling they would have embraced change and all the excitement and energy that comes with it.

Delos

Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

There is a point when winter turns and spring takes over. It inches at first, and then that false feeling – that you have time on your hands – begins to evaporate. This year I have been watching for the change more intently than usual, because we had a date in the diary to plant up the first phase of the new garden; the week of the spring equinox which, this year, proved to be perfect timing. One week later and the peonies were already a foot high and the tight fans of leaf on the hemerocallis were flushed and beyond moving without setting them back.

I have been planning for this moment for three years, perhaps longer in refining the idea of the way I wanted the planting to nestle the buildings and blend with the land beyond. I procrastinated over the final plant list for as long as it was possible, but in January it finally went out to the nurseries in time to get the stock I needed for spring.

The process of refining a plant palette is one that I know well, but committing a plan to paper is an altogether more difficult thing to do for yourself than for a client. I decided not to make an annotated plan, but instead to map a series of areas that shift in mood as you walk the paths. I paced the space again and again to understand where the ground was most exposed, where it was free-draining and to note that, in the hollow where the ground swung down to the track, there was running water a spit deep this winter. I imagined where I would want height and where I would need the planting to dip, sometimes deep into the beds, to give things breathing space. There would also need to be countermovements across the site, with tall emergent plants brought to the foreground, close to the paths.

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The preparation was completed the week before the plants arrived; the soil dug in the windows when it was dry enough and then knocked out level just in time. We prayed that the weather would dry up, because the soil had lain wet all winter and would not stand footfall if it stayed that way. In tandem with the soil preparation we moved some favourites that I have been bulking up, like the Paeonia mlokosewitschii and Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’, both of which came with us from Peckham, and split those plants that had passed the test in the trial garden. A three year old Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ was easily divided into eight, and so three plants gave me twenty four to play with; enough to move from bed to bed and to jump the path. The same with the persicarias, the Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’, the Aster turbinellus and a long list of others. These were bagged up individually so that I could afford to leave them laid out when shifting the planting around on the day of laying out.

Due to the size of the site this was just the first round of planting, and of only half the garden. The remaining half will be planted this autumn. The plan for this lower half comprises a dozen interlocking areas, which allow my combinations to vary subtly across the site and flow into one another to form a related whole. Before starting, the boundaries were sprayed onto the soil with a landscape marker, although I break these boundaries during setting out, jumping plants across to knit them together.

Shrubs and woody plants were positioned first to articulate the space. Trees by the gates including Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’ and Crataegus coccinea, some Malus transitoria and Rosa glauca breaking in from high up, and home-grown whips of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Salix gracilistyla fraying the edges alongside the field. Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’, the largest of the clump forming grasses, was also given its position early to tie the meeting point of the paths together.

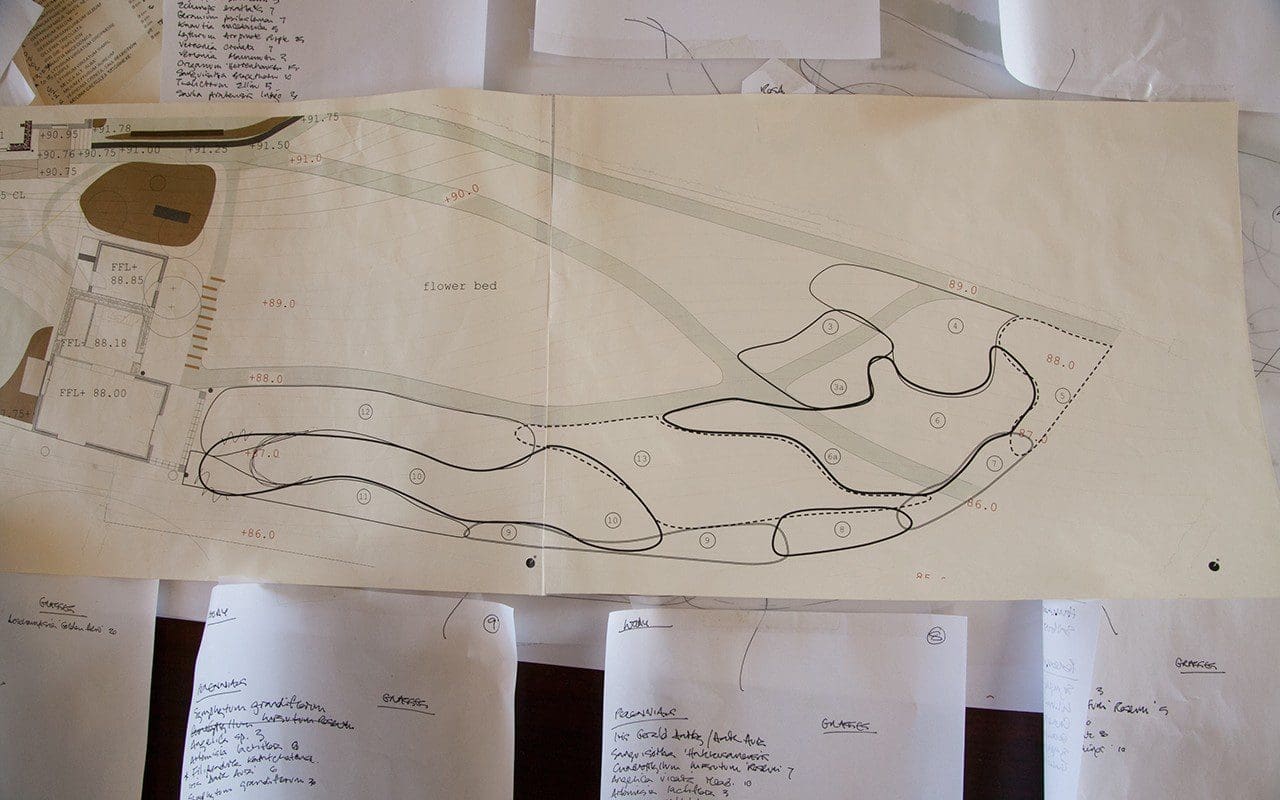

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

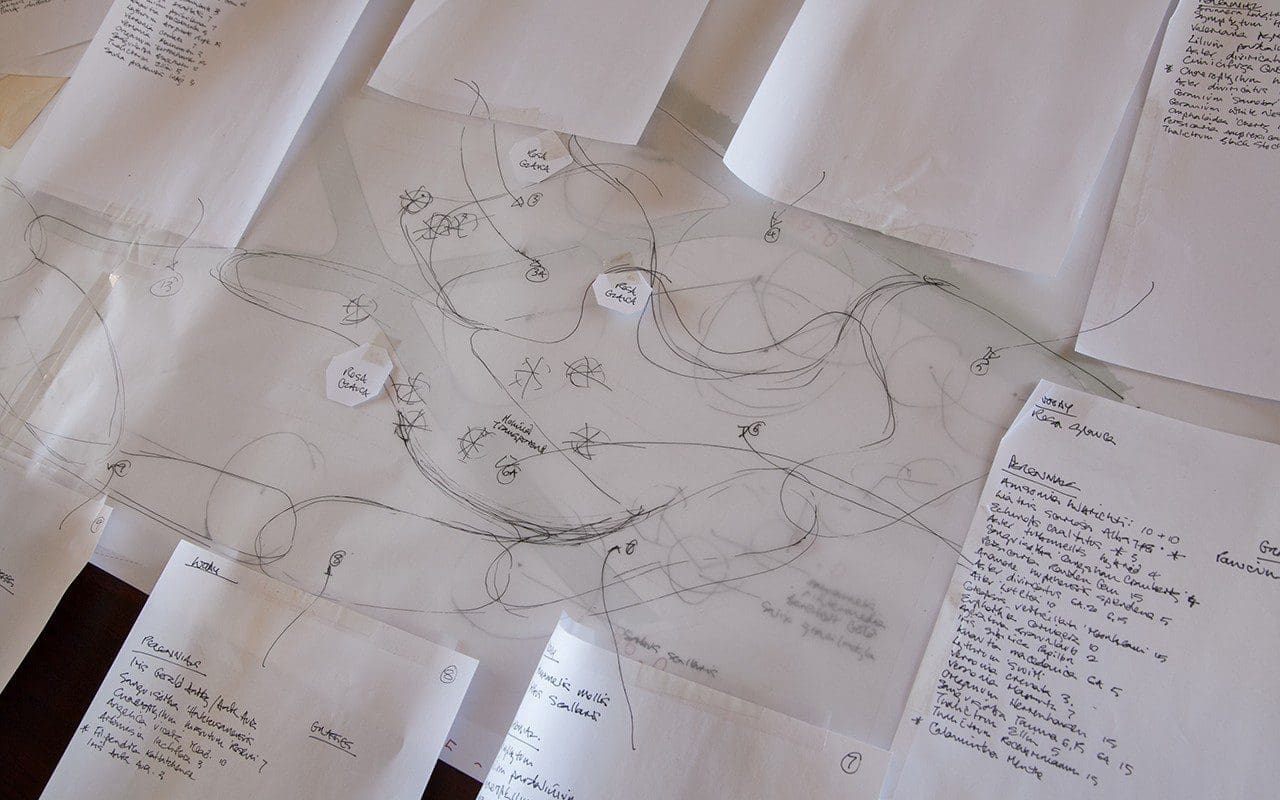

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

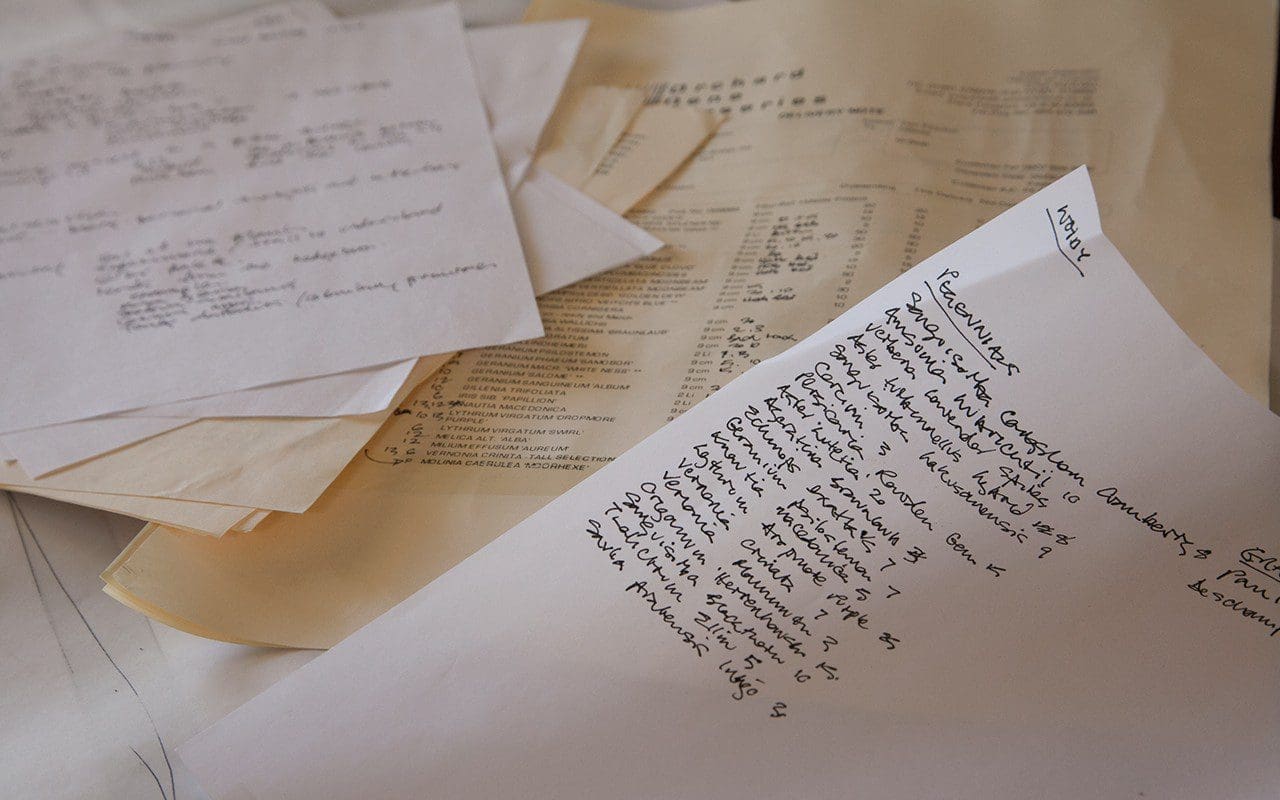

Plant lists and orders

Plant lists and orders

For each of the zones I made a list that quantified all of the plants I would need to make it special. A handful of emergents to rise up tall above the rest; Thalictrum ‘Elin’, Vernonia crinata, sanguisorbas and perpetual angelicas. When laying out these were the first perennials placed to articulate the spaces between the shrubs and key grasses.

Next, the mid-layer beneath them, with the verticals of Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Rowden Gem’, and the mounding forms of aster (A. divaricatus) or geranium (G. phaeum ‘Samobor’, G. psilostemon and G. ‘Salome’). The plants that will group and contrast. And finally, the layer beneath and between, to flood the gaps and bring it all together. These were a freeform mix; fine Panicum ‘Rehbraun’ with Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Tanna’, or Viola cornuta ‘Alba’, Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ and the white bloody cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum ‘Album’.

The plants arrived from Orchard Dene Nurseries and Arvensis Perennials on the Friday. Immaculate and ready to go and filling up the drive. I like to plant small with nine centimetre pots. If you get the timing right, and don’t have to leave them sitting around, this size is easily trowelled in with minimum soil disturbance. At close spacing this makes planting easier and faster than having to spade in a larger plant.

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants grouped by planting zone

Plants grouped by planting zone

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

It took us two days to complete the lifting and dividing of my stock plants and to set the plants on the paths in their groups. And the process was prolonged as I started adding last minute choices from the stock beds. On the Sunday high winds whistled through the valley to dry the soil, so I started setting out and hoped that the pots didn’t blow into one corner overnight, as once happened in a client’s garden. On the Monday, and ahead of my team of planters who were arriving the next day, I continued to populate the spaces, between the heavens opening up and pouring stair-rods. It was hard, and there was a moment I despaired of us being able to get the plants in the ground at all.

Setting out plants is one of the most all-consuming and taxing activities I know. It feels like it uses every available bit of brain-space. You not only have to retain and visualise the various volumes, cultural requirements and habits of the individual plants, but also the sequencing and rhythm of a planting, how it rises and falls, ebbs and flows, and then how each area of planting relates to the next, in three dimensions and from all angles. Add to this the aesthetic considerations of colour relationships both within and between areas and the time-travel exercise of imagining seasonal changes and there is only so much I can do in one session. However, I was ahead of my planters and, as long as I could hold my concentration once they arrived, it would stay that way with them coming up behind me. The rains abated, the wind continued and the following day the soil was dry enough for planting.

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Jacky Mills

Jacky Mills

Ian Mannall

Ian Mannall

Ray Pemberton

Ray Pemberton

On the 21st, the sun broke through not long after it was up. A solitary stag silhouetted against the sky looked down on us from the Tump as we readied for the day. Clearly word had already got out that there were going to be rich new pickings in the valley.

Over the course of two days about twelve hundred plants went in the ground. Three people planting and myself managing to stay ahead, moving the plants into position in front of them. Thank you Ian, Jacky and Ray for your hard work, and Huw for supplying a constant supply of necessary vittles.

I cannot tell you – or perhaps I can to those who know this feeling too – what a huge sense of excitement is wrapped up in a new planting. Plans and imaginings, old plants in new combinations, new plants to shift the balance. All that potential. All those as yet unknown surprises.

Already, the space is changed. We will watch and wait and report back.

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Sharp winds have whipped the blossom and pushed and pulled the tender young growth on the epimediums. So often is the way of early April. The cruellest month perhaps but, in its awakening flora, the most exquisite.

Some of my favourite plants are having their moment now. Woodlanders mostly, making the best of bright spring light flooding to the floor ahead of the canopy closing over. The plants that seize this window are ephemeral by nature and you have to steel yourself for not wishing that time would slow. Picking a posy helps to make a close observation of these long-awaited treasures.

Our garden is young and I have just a few square metres of shelter. The pockets close to the studio have to suffice until we gain the protection of new trees and a sliver of shade in the lea of the house is where I keep the Asian epimediums. I have a collection of twenty or so plants, grown against the odds and carefully looked after in pots. I am sure they would perish out in the open, for they are altogether more delicate than their European counterparts, needing a stiller atmosphere and more reliable moisture at the root in the summer.

My efforts to keep them in good condition – namely shelter from wind and trays in the summer to keep the pots moist when I am not here to water – is all the attention they get. Other than picking over the dead foliage in the spring and a monthly liquid feed in summer, they reward me handsomely for this light intervention. Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ was the first to flower. I do not know this plant well yet, but it has flourished for me in the couple of years I have been growing it, forming a neat, low mound of leaf and throwing out charteuse young foliage with delicate red marbling. The large, dancing flowers, held out sideways on wiry stems, are a strong, rose pink with white inner spurs.

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ foliage

Epimedium leptorrhizum ‘Mariko’ foliage

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ is much better known to me and the spray in this posy is from the plant I brought with me from my Peckham garden. It is particular in its long, serrated, shield-shaped foliage, which is sharp on the eye yet not to the touch. Three leaflets to a stem and burnished copper when they emerge, they darken to a shiny, holly-green for summer. The flowers, of palest pink, are well named and staccato in appearance, arranged candelabra-like on long, wire-thin stems. They sport dark purple inner spurs and the creamy beak of stamens terminates in unexpected turquoise pollen.

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ flower detail

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ flower detail

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ foliage

Epimedium fargesii ‘Pink Constellation’ foliage

The Vinca major var. oxyloba is altogether more robust and the plant from which these flowers are taken is one I have introduced into the hedgerow alongside the garden. The original came from The Garden Museum and, having seen it take a hold there, the hedge seems like the best place for it. Beth Chatto’s catalogue lists it as having an ‘indefinite spread’ and sure enough it has jumped and moved already, rooting wherever it touches down. Certainly not one for introducing into the garden. A gate to either end of the hedge, a verge and mown path to either side, will kerb its domain, if it ever gets that far. I prefer it to straight Vinca major for it’s finely-rayed, starry flowers, which are an intense inky purple that vibrates in shade. It has been in flower now since late December.

Vinca major var. oxyloba and Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’

Vinca major var. oxyloba and Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’

The name of Corydalis temulifolia ‘Chocolate Stars’ refers to the colour of the foliage, which is perhaps its greatest asset, springing to life ahead of everything else with a lushness that is out of kilter with the season. I welcome its luxuriance and have it with the liquorice-leaved Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’ and my best yellow hellebore, for which it was a good foil early on. I used it at the Chelsea Flower Show a couple of years ago with Vinca major var. oxyloba, amongst cut-leaved brambles on a shady rock bank of Chatsworth gritstone. The pale lilac flowers were nearing the end of the season and it had lost its April vitality which, right now, makes you stop and draw breath.

Fritillaria meleagris

Fritillaria meleagris

This is the second year the snakeshead fritillaries (Fritillaria meleagris) have flowered for us on the banks behind the house. They will not show evidence of seeding for a few years yet but, in the meantime, I will add to the colony to increase its domain in the short turf beneath the crabapples. They are one of my favourite spring flowers, the chequering of the petals more marked on the purple forms, less so but in evidence, green on white, with the albas. They have a medieval quality to them that must have inspired textiles and paintings. And when the wind blows, despite their apparent delicacy, they are oblivious.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The Blossom Wood was one of my first projects here. Plant trees at the beginning of a project and by the time you have started to round the corner, you have time mapped in growth and your efforts rewarded in the satisfaction of being able to stand in the beginnings of their shadow. Such has been the case here and now, in the sixth spring after planting, we can already walk into the corner of our top field and find a place transformed into the start of somewhere new.

The idea behind the little wood was that it be a sanctuary; for birds, insects, mammals and ourselves. The fields were all but empty when we arrived. You could see from corner to corner and there was no shade other than the fingers borrowed from our neighbour’s trees across the stream. The birds had to hop from hedge to hedge and it was quickly clear that we needed somewhere that they could call home on our side of the stream.

Save the occasional hawthorns that have matured into trees where they have been left in the hedgerows, we all but miss the blossom season and the celebration of spring that comes with it. So all the trees and their associated understorey are native and I have aimed for everything (save a handful of field maples, some spindle and an oak or two) to flower conspicuously and then provide berries for autumn.

The site of the Blossom Wood in 2011

The site of the Blossom Wood in 2011

Planting the whips in January 2012

Planting the whips in January 2012

The Blossom Wood in spring 2016

The Blossom Wood in spring 2016

The Blossom Wood in 2014

The Blossom Wood in 2014

The same view in 2016

The same view in 2016

The cherry plum, Prunus cerasifera (main image), breaks with winter. The buds, pinpricks of hope, swell at snowdrop time. Early on we picked twigs and, now that they are grown, whole branches to bring into the house to force with willow and hazel catkins. After a couple of days in the warmth they pop, pale on dark twiggery and smelling of almonds. Prunus cerasifera is the parent of the Mirabelle plum, which is the first tree to flower in the plum orchard too. It is so worth this early life, which can sometimes appear in the last week of February, but the trees are always billowing by the middle of March.

Rather than the wood erupting all at once the flowering sequence is staggered and broken so that, from the cherry plum now, until June when the wayfaring tree, guelder rose and sweetbriar are flowering, there is always something to visit. If I had left blackthorn in the mix it would be the next to flower, but I removed them after they showed early signs of running. Better to have them in a hedge that can be cut from both sides and where their tiny sprays of creamy flower appear with the most juvenile pinpricks of green on the breaking hawthorn. The hawthorn and the native Cornus sanguinea are fast and have been used as nurse companions to provide shelter to the slower growing species. I want to see how this place evolves unaided, so have decided not to intervene, but I will probably coppice a number to make some more space if I see anything suffering that I need for the long term.

Cherry Plum – Prunus cerasifera

Cherry Plum – Prunus cerasifera

Wayfaring Tree – Viburnum lantana

Wayfaring Tree – Viburnum lantana

Guelder Rose – Viburnum opulus

Guelder Rose – Viburnum opulus

The wild pear, Pyrus pyraster, is a tree I do not know well but have already learned to love. It flowered for the first time last year, a smattering here and there, but I hope for more this spring. Pear flowers are one of the most exquisite of all spring blossoms, the milky flowers, round and ballooning fat in bud and then cupped and beautifully drawn with stamens. The flowers often occur with the very first leaves, lime green and creamy white together. You can see the trees are going to be something. ‘Plant pears for your grandchildren’ they say, for they take time to fruit and go on to live to a very great age. My youngsters, which I planted with all the other trees as whips, are well over twice my height, stocky at the base and showing stamina.

As spring opens up and first foliage flushes, we have wild gean, Prunus avium, to make the transition from leaflessness. The trees are racing up, bolting visibly with each year’s extension growth and already taller than most in the mix. The flowers are fleeting, lasting just half the time of the beautiful double selection ‘Alba Plena’. The wild gean is beautiful though, whirling at the ends of the branches, the flowers are finely held on long pedicels and dance in the breeze. Next comes the bird cherry, Prunus padus, with long sprays of creamy blossom. I have it on the lower, damper ground where it is happiest.

Wild Pear – Pyrus pyraster

Wild Pear – Pyrus pyraster

Wild Gean – Prunus avium

Wild Gean – Prunus avium

Bird Cherry – Prunus padus

Bird Cherry – Prunus padus

Three sorbus follow and come into flower once the wood has flushed with leaf. Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) with its feathery foliage is planted close to the pears, which will eventually take over. Despite the fact that rowan are said to be long-lived, in my experience, on rich ground and in combination with other species, I have found them to be quick off the mark at first, but affected by the competition later. I wanted to plant whitebeam (Sorbus aria) with the gean because I love the blossom and silveryness of the newly emerging sorbus foliage together. However, now that these trees are maturing and fruiting, I see that I have been mis-supplied with Sorbus x intermedia, a Swedish native. No matter, they are magnificent fruiters, bright scarlet in autumn. The chequer, or wild service, tree (Sorbus torminalis) is the third. Now a very rare tree in the wild, mainly confined to ancient oak and ash woodland, it is a delightful thing, with leaves more like a maple and marble-sized russet fruit that, from medieval times until fairly recently, were bletted and used as dessert fruit (reputed to taste like dates) or to make beer. My young trees are slender and have only just started flowering, but I have a feeling they will become a favourite. I have given them room to fill out and mature without competition.

Rowan – Sorbus aucuparia

Rowan – Sorbus aucuparia

My childhood friend Geraldine left me a few hundred pounds in her will when she died and I put it into planting the wood. A naturalist to the core, I know she would approve of this place which is the domain of wildlife and where the gardener is just a visitor. We find ourselves very much the interlopers here when we visit, disturbing flurries of the birds I’d hoped for, and seeing the tell-tale signs of unseen badgers and of deer seeking cover in the soft beds of grass where I have deliberately left a couple of clearings. I know already that I will be cursing them when they become bolder and find the garden, but it is good to see that, in less than a decade, we have a place that lives up to its name.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

At this time of year there are two major challenges in the kitchen garden; how to use up the remaining winter vegetables in order to clear the beds for the sowing of new crops, and how to bridge the hungry gap, as we reach the end of our stores. Most of the remaining vegetables have been sitting in the ground or in storage for the best part of five months and as the days start to lengthen and warm, we crave the flavours of spring.

The trick to bridging the gap is to combine these winter vegetables with fresher, spring ingredients; roast beetroot with fresh horseradish and watercress, or a plate of sautéed carrots with blood oranges and the last cobnuts.

This recipe is an adaptation of one I usually make with purple sprouting broccoli. However, ours has been a disappointment this year as we sowed a couple of weeks too late and the plants failed to gain enough stature before the winter. The cavolo nero would also have done better with a fortnight more of summer. Although we’ve harvested a few good helpings of leaves we have learned not to uproot it too early, since we have found it has a second season and has been shooting furiously for the past few weeks as it readies itself to flower. The young cavolo shoots are best before all the energy goes into the flower so pick when you see the first buds to retain the velvety texture of the young growth. At the end of winter it has has a mineral richness, which is a good partner to the wild garlic that is now showing itself down by the stream.

Gnocchi are quick and easy to make yourself and a great way to use up the last of the potatoes. It is best to use a floury variety or the gnocchi will be gluey, but I made do with ‘Roseval’, the last of our stored potatoes, which is somewhat waxy. As long as you rice the potatoes while piping hot they still lose a lot of their moisture.

Served with a sharply dressed salad of bitter leaves this makes a perfect spring lunch.

INGREDIENTS

GNOCCHI

500g potatoes, preferably a floury variety like Desirée

1 large or 2 small organic egg yolks

75g Tipo 00 pasta flour

50g semolina

35g (a small handful) wild garlic leaves, finely chopped

Salt

TO SERVE

250g ricotta

100g cavolo nero shoots or purple sprouting broccoli

Olive oil

Pecorino cheese, finely grated

Serves 4 or 6 as a starter

METHOD

To make the gnocchi cook the potatoes in their skins in a large pan of boiling water. Drain and peel them while still hot. Protect your hand with a tea towel or oven glove. Immediately put them through a potato ricer or mouli into a large mixing bowl. Add the egg yolk, flour, semolina, wild garlic and salt and fold through with a metal spoon until well combined. Using very light movements use your hands to quickly bring the dough together into a ball. Do not knead it or the gnocchi will be heavy.

Divide the dough into four. On a floured worktop roll the first quarter into a sausage a little thicker than your index finger, then cut into 2cm pieces with a sharp knife. Take each piece and, pushing away from you, roll them on the back of a fork to create ridges which will hold some of the sauce. Place them on a floured tray. Repeat with all of the dough.

Bring two large pans of generously salted water to the boil. In the first one cook the gnocchi in batches. They are done when they float to the surface. Remove with a slotted spoon and drain them on a clean tea towel while you cook the rest.

As you cook the last batch of gnocchi put the cavolo nero shoots in the other pan of boiling water for two minutes. They should retain some bite. Drain, refresh in cold water and drain again. If using purple sprouting broccoli remove the small florets from the larger stems and cut any larger florets in half or quarters.

Put the gnocchi and cavolo nero shoots into a bowl. Add the ricotta in spoonfuls. Season with salt, ground pepper and a little olive oil. Stir gently to coat adding a little reserved cooking water to loosen if necessary.

Divide the gnocchi between hot plates. Drizzle with olive oil and finish with grated pecorino.

Recipe & Photography: Huw Morgan

Yellow breaks with winter. Soft catkins streaming in the hazel. Brightly gold and blinking celandines studding the sunny banks. They are shiny and light reflecting and open with spring sunshine. As strong as any colour we have seen for weeks and welcome for it.

There is more to come, and in rapid succession, now that spring is with us. The first primroses in the hollows and dandelions pressed tight in grass that is rapidly flushing. Daffodils in their hosts, pumping up the volume and forsythia, of course, at which point I begin to question the colour, for yellow has to be handled carefully.

Lesser Celandine – Ranunculus ficaria

Lesser Celandine – Ranunculus ficaria

In all my years of designing it is always yellow that clients most often have difficulty with. ‘I really don’t like it’. ‘I don’t want to see it in the garden’. ‘Only in very small amounts’. Strong language which points to the fact that it prompts a reaction. Colour theory suggests the yellow wavelength is relatively long and essentially stimulating. The stimulus being emotional and one that is optimistic, making it the strongest colour psychologically. Yellow is said to be a colour of confidence, self-esteem and emotional strength. It is a colour that is both friendly and creative, but too much of it, or the wrong shade, can make you queasy, depressed or even turn you mad.

Whether I entirely believe in the thinking is a moot point, but I have found it to be true that yellow is a positive force when used judiciously. My first border as a teenager was yellow. I experimented with quantity and quality and by contrasting it with magenta and purple, it’s opposites. Today I weave it throughout the garden, using it for its ability to break with melancholy; a flash of Welsh poppy amongst ferns or a carefully selected greenish-yellow hellebore lighting a shaded corner.

Helleborus x hybridus Ashwood Selection Primrose Shades Spotted

Helleborus x hybridus Ashwood Selection Primrose Shades Spotted

I remember talking to the textile designer, Susan Collier, about the use of yellow in her garden in Stockwell. She had repeated the tall, sulphur-yellow Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum throughout the planting and explained how she used it to draw the eye through the garden. ‘Yellow in textile design is extraordinarily persistent. It is noisy, but it lifts the heart. It causes the eye to wander, as the eye always returns to yellow.’

At this time of year, I am happy to see it, but prefer yellow in dashes and dots and smatterings. I will use Cornus mas, the Cornelian cherry, rather than forsythia, and have planted a little grove that will arch over the ditch in time and mingle with a stand of hazel. The fattening buds broke a fortnight ago, just as the hazel was losing its freshness. Ultimately, over time, my widely spaced shrubs will grow to the size of a hawthorn, the cadmium yellow flowers, more stamen than petal, creating a spangled cage of colour, rather than the airless weight of gold you get with forsythia.

We have started splitting the primroses along the ditch too. I hope they will colonise the ground beneath the Cornus mas. I have a hundred of the Tenby daffodil, our native Narcissus obvallaris, to scatter amongst them. The flowers are gold, but they are small and nicely proportioned. Used in small quantity and widely spaced to avoid an obvious flare, they will bring the yellow of the cornus to earth.

Narcissus obvallaris with Cornus mas (Cornelian cherry)

Narcissus obvallaris with Cornus mas (Cornelian cherry)

Primrose – Primula vulgaris

Primrose – Primula vulgaris

After several years of experimenting with narcissus, I have found that they are always best when used lightly and with the stronger yellows used as highlights amongst those that are paler. N. bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’, a delightful pale hoop-petticoat daffodil is first to flower here and a firm favourite. I have grown them in pans this year to verify the variety, but will plant them on the steep bank in front of the house where, next spring, they will tremble in the westerly winds.

Narcissus bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’

Narcissus bulbocodium ‘Spoirot’

The very first of the Narcissus x odorus and Narcissus pallidiflorus are also out today, braving a week of overcast skies and cold rain. The N. pallidiflorus were a gift from Beth Chatto. She had been gifted them in turn by Cedric Morris, who had collected the bulbs on one of his expeditions to Europe. The flowers are a pale, primrose yellow, the trumpet slightly darker, and are distinguished by the fact that they face joyously upwards, unlike their downward-facing cousins.

Narcissus x odorus

Narcissus x odorus

Narcissus pallidiflorus

Narcissus pallidiflorus

Our other native daffodil Narcissus pseudonarcissus has a trumpet the same gold as N. obvallaris, but with petals the pale lemon hue of N. pallidiflorus. It has an altogether lighter feeling than many of the named hybrids for this gradation of colour. We were thrilled to see a huge wild colony of them in the woods last weekend, spilling from high up on the banks, the mother colony scattering her offspring in little satellites. This is how they look best, in stops and starts and concentrations. I am slowly planting drifts along the stream edge and up through a new hazel coppice that will be useful in the future. A move that feels right for now, with all the energy and awakening of this new season.

Narcissus pseudonarcissus (top), Narcissus obvallaris (bottom)

Narcissus pseudonarcissus (top), Narcissus obvallaris (bottom)

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Clockwise from bottom left: Centaurea montana ‘Lady Flora Hastings’, Meconopsis cambrica, Tragopogon crocifolius, Camassia leichtlinii ‘Alba’, Amsonia orientalis, Symphytum x uplandicum ‘Moorland Heather’, Ranunculus acris & Valeriana pyrenaica

The Chelsea Flower show usually falls in a week that is suspended between spring and summer. That is one of the things that gives the show its charge, the freshness and feeling of anticipation. I was not involved this year other than as a spectator and it was a delight to return home after a busy week of looking to find that we are still in this teetering point and haven’t missed the moment.

Marking it with today’s posy brings the meadows and the garden together. Ranunculus acris, the meadow buttercup, is at it’s zenith. It is one of my favourite components in the grassland, rising up tall above it’s neighbours this early in the season. Where we have over-seeded the old pastures with meadow seed from the neighbouring valley, the buttercup is now in evidence three years on. I like the way it is so light on its feet and that there is so much air amongst the bright pinpricks of yellow.

I have brought it up close on the vegetable garden banks and used it to bring together the clumping Valeriana pyrenaica, which I am trying to naturalise in the grass. This European species has been grown in Britain since at least 1692, and was first recorded in the wild in 1782 as a supposed native, and it could easily be part of our landscape. It has been in flower for a month now and though you wouldn’t think that the brightness of the buttercup would sit well with the lilac pink of the valerian, such colour clashes are commonplace in wild plant communities.

I also have it growing alongside the Symphytum x uplandicum ‘Moorland Heather’ close to the compost heaps. This is a chance seedling of our native comfrey found at Moorland Cottage Plants in South Wales. I first saw it at the Chelsea show and was taken by its darker violet flowers which are alive with bees. It is not allowed to seed as it is a coloniser and the roots grow deep, pulling minerals up into the foliage which, when harvested, make a fine green manure or compost tea. Before the plants set seed, all the growth is cut to the ground and used as a mulch or green manure to turn into the soil. To make an evil smelling brew of compost tea, fill a large plastic bucket to the top with it, trample down and fill with water. Allow it to ferment and then skim off the pungent liquid feed rich in nitrogen, potassium, phosphorous and calcium.

I have Camassia leichtlinii ‘Alba’ growing in the grass under the crab apples. They are at their best this week as the crabs are fading, racing up their stems like sparklers almost as fast as you can enjoy them. I like the creaminess of the flowers and this single form the best. I have made the mistake of planting it in open ground amongst perennials and had a million and one seedlings to contend with. The double form is sterile and better in the beds, but I’m hoping that the singles will seed into the grass where it runs thin with yellow rattle.

I might try Centaurea montana ‘Lady Flora Hastings’, Amsonia orientalis and Tragopogon crocifolius together as they are currently disparate in the garden. This is the first time I have thought of doing so and the advantage of throwing things together in a bunch. Amsonia has a short moment of flower, but great longevity of life as a plant and the tragopogon is a delightful self-seeding biennial that adds flux to the mix. ‘Lady Flora Hastings’ is perhaps one of the best centaureas, flowering for weeks and then again if you cut it to the base when it starts to look tired. Like the comfrey its roots run deep and come easily as cuttings. Move the parent plant and it will reappear with the certainty of a perennial that will probably outlive you if you find it a place in sunshine that suits.

The Welsh poppy, Meconopsis cambrica, is at is peak in these first few weeks of the growing season. My plants were strewn as seed on bare earth a couple of years ago and are naturalising happily. They are best when emerging as an incidental in places where other plants might think twice about flourishing. Cracks between paving see them at their happiest and they are unflinching in dry shade. They also thrive in full sun, but I prefer their pure, clean yellow when it sparkles in shadow.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

When we arrived here, the house sat alone on the hill. Only the hollies by the milking barn and a pair of old plums in the hedge alongside the house stood sentinel, catching the wind and the rummage of seasonal blackbirds and pigeons. As we moved here in winter it took a while to realise that bird song comes only from a distance and from the refuge of the hedges, which run along the lane and the field margins. Walking down the slope in front of the house that first spring, we soon heard that it is the wood below us that provides the haven for birds. I was brought up in woodland and so am familiar with its qualities. The sound of wood pigeons close to the bedroom windows, the constant activity of bird life in the branches, wind caught in leaves, the movement of dappled light and shade. Living in London was as intimate in its own way; the world around us so close and connected and plants pressed up against the windows. Although I love the country contrast of letting my eye travel here, I struggled initially with the degree of openness surrounding us. Not only was the space acoustically different, the feeling of exposure was unfamiliar and begged understanding. I knew early on – certainly within a couple of months – that we needed trees around us, and herein lay a conundrum. Plant indiscriminately and I was at risk of foreshortening the views that had made us fall in love with the property. But, perched on our hillside, we needed to hunker the house down, to feel as you do when settled into a high-backed sofa, with the feeling of comfort enveloping you whilst still being part of the room. Malus transitoria on the slope behind the house

Before the first winter was out, I ordered a dozen crab apples to make a huddle of trees on the slope behind the house. It took much deliberation to decide where they should go. The track leading to the tin barns provided the anchor point between the hedge on its lower side and the open banks above it. The new trees would add an upper storey to the hedge and provide the shelter for a bat corridor. At roughly eight paces between them, they would also offer an easy hop from one to another for the birds.

As has become the way here, I staked out their positions with six-foot canes topped with hazard tape so that they are easy to see from a distance. I wanted the trees to arch over the track eventually, like the old holloways hereabouts, to provide a tunnel of blossom in spring and a shady place to emerge from into the light in summer. I didn’t want them in rows or for them to feel organised like an orchard. Over the course of a month the markers were moved about and the sight lines tested until the placement felt right. The crabs were suitable for feeling productive, but I also wanted them to have a connection with the hawthorns in the top hedgerow that we had allowed to grow out to provide shade for the livestock in summer.

Malus transitoria on the slope behind the house

Before the first winter was out, I ordered a dozen crab apples to make a huddle of trees on the slope behind the house. It took much deliberation to decide where they should go. The track leading to the tin barns provided the anchor point between the hedge on its lower side and the open banks above it. The new trees would add an upper storey to the hedge and provide the shelter for a bat corridor. At roughly eight paces between them, they would also offer an easy hop from one to another for the birds.

As has become the way here, I staked out their positions with six-foot canes topped with hazard tape so that they are easy to see from a distance. I wanted the trees to arch over the track eventually, like the old holloways hereabouts, to provide a tunnel of blossom in spring and a shady place to emerge from into the light in summer. I didn’t want them in rows or for them to feel organised like an orchard. Over the course of a month the markers were moved about and the sight lines tested until the placement felt right. The crabs were suitable for feeling productive, but I also wanted them to have a connection with the hawthorns in the top hedgerow that we had allowed to grow out to provide shade for the livestock in summer.

Malus transitoria

I had been looking at crab apples for quite a few years in a search of a blossom tree that was neither cherry nor amelanchier, which had become my reflex choices when planting blossom for clients. There is a wealth of crabs to choose from and, although I knew Malus ‘Evereste’, ‘John Downie’ and ‘Hornet’ from gardens I had worked at or visited, I wanted mine to be on the wild side, and so I honed my selection to what are probably the best two species.

Malus transitoria was chosen specifically for its wilding quality and, of the two species on the bank, it opens a few days earlier than its partner. Known as the cut-leaf crab apple its leaves are slim and divided, not entire like the usual apple foliage, and could easily be mistaken for hawthorn. They have a lacy quality and so the tree retains a lightness when in leaf. The flowers are pale pink in bud and, though small, completely cover the tree and open in a glorious froth to weight the branches with pure white blossom. The petals are narrow and separate, splayed around a burst of orange-tipped anthers, giving the flowers a star-like quality. After flowering you could easily think the trees were native, but the tiny fruits give them away in autumn when the amber beads pepper the yellowing branches.

Malus transitoria

I had been looking at crab apples for quite a few years in a search of a blossom tree that was neither cherry nor amelanchier, which had become my reflex choices when planting blossom for clients. There is a wealth of crabs to choose from and, although I knew Malus ‘Evereste’, ‘John Downie’ and ‘Hornet’ from gardens I had worked at or visited, I wanted mine to be on the wild side, and so I honed my selection to what are probably the best two species.

Malus transitoria was chosen specifically for its wilding quality and, of the two species on the bank, it opens a few days earlier than its partner. Known as the cut-leaf crab apple its leaves are slim and divided, not entire like the usual apple foliage, and could easily be mistaken for hawthorn. They have a lacy quality and so the tree retains a lightness when in leaf. The flowers are pale pink in bud and, though small, completely cover the tree and open in a glorious froth to weight the branches with pure white blossom. The petals are narrow and separate, splayed around a burst of orange-tipped anthers, giving the flowers a star-like quality. After flowering you could easily think the trees were native, but the tiny fruits give them away in autumn when the amber beads pepper the yellowing branches.

Malus hupehensis

Malus hupehensis, the Chinese tea crab, is the best crab apple according to experienced tree people and another fine discovery of the great plant hunter, Ernest Wilson. Wilson had impeccable taste and the tree, which is quite substantial in maturity, is a spectacle in flower. Once again it is pink in bud, but a stronger shade so that, from a distance, the tree appears pale pink. The flowers are altogether more flamboyant, large and bowl-shaped, hanging gracefully on long pedicels and blowing open to a pure, glistening white flushed with pink. When a tree is in bud and flower, it is a breathtaking moment. The flowers have a deliciously fresh perfume, as welcome as newly mown grass in this window between spring and summer.

Malus hupehensis

Malus hupehensis, the Chinese tea crab, is the best crab apple according to experienced tree people and another fine discovery of the great plant hunter, Ernest Wilson. Wilson had impeccable taste and the tree, which is quite substantial in maturity, is a spectacle in flower. Once again it is pink in bud, but a stronger shade so that, from a distance, the tree appears pale pink. The flowers are altogether more flamboyant, large and bowl-shaped, hanging gracefully on long pedicels and blowing open to a pure, glistening white flushed with pink. When a tree is in bud and flower, it is a breathtaking moment. The flowers have a deliciously fresh perfume, as welcome as newly mown grass in this window between spring and summer.

Malus hupehensis (and main image)I like to plant my trees as young feathered maidens. This is one stage further on from a whip, so the trees have their first side branches and stand about a metre twenty high. They are easy to handle at this size and with care they establish quickly to outstrip a more mature tree planted for immediate affect.

Malus hupehensis (and main image)I like to plant my trees as young feathered maidens. This is one stage further on from a whip, so the trees have their first side branches and stand about a metre twenty high. They are easy to handle at this size and with care they establish quickly to outstrip a more mature tree planted for immediate affect.

Malus hupehensis, the Great Dixter form

That first winter I planted the crabs I didn’t know that there are two forms of Malus hupehensis. It was one of Christopher Lloyd’s favourite trees and, naturally, he selected a superior form. Those that shade the car park at Great Dixter are smaller berried, with deep red fruit half the size of the marble-sized fruits on my form. At this size, they are more easily eaten by birds and, had I known, I would have preferred them for the track behind the house for the rush of bird life come the autumn.

Malus hupehensis, the Great Dixter form

That first winter I planted the crabs I didn’t know that there are two forms of Malus hupehensis. It was one of Christopher Lloyd’s favourite trees and, naturally, he selected a superior form. Those that shade the car park at Great Dixter are smaller berried, with deep red fruit half the size of the marble-sized fruits on my form. At this size, they are more easily eaten by birds and, had I known, I would have preferred them for the track behind the house for the rush of bird life come the autumn.

Malus hupehensis, the Great Dixter form

Look closely and you see that the Dixter trees are more elegant in all their parts; the branches are finer and the tree more open, the leaves are elongated and flushed with bronze when young, and the flowers are slightly fuller, a purer white in bud and open, and with longer pedicels that allow them to tremble exquisitely in the wind. Of course, I bought a couple from the nursery as soon as I saw them. One as an entrance tree by our front gate and the other on the edge of the blossom wood, where it is visible from the house. I already have seedlings from these trees in the cold frame, as they come easily and true from seed. Totally smitten, as time goes on I plan to extend their influence.

Malus hupehensis, the Great Dixter form

Look closely and you see that the Dixter trees are more elegant in all their parts; the branches are finer and the tree more open, the leaves are elongated and flushed with bronze when young, and the flowers are slightly fuller, a purer white in bud and open, and with longer pedicels that allow them to tremble exquisitely in the wind. Of course, I bought a couple from the nursery as soon as I saw them. One as an entrance tree by our front gate and the other on the edge of the blossom wood, where it is visible from the house. I already have seedlings from these trees in the cold frame, as they come easily and true from seed. Totally smitten, as time goes on I plan to extend their influence.

“…it is very beautiful in spring when covered with light pink flowers, and resembles at this time a flowering cherry rather than an apple tree; the effect of the flowers is heightened by the purple calyx and the purplish tints of the unfolding leaves.”

—Ernest Wilson of Malus hupehensis

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

The green sauce in this recipe is not the well known mediterranean salsa verde, but Grüne Sosse, a speciality of Frankfurt introduced to me by our friend Ariane, a native of the city, and a neighbour in Bonnington Square for many years. It is traditionally served with asparagus of the forced white variety, which is particularly prized in Germany, where Spargelfesten are held in its honour every spring. Although green sauce made from a variety of herbs can be found in German restaurants all year round, it is only in early spring that the truly authentic sauce can be made, when the herbs required are coming into their prime and the paper packages of them required to make it are found in farmer’s markets, together with the white asparagus which it traditionally accompanies.

Genuine Grüne Sosse requires seven specific herbs; sorrel, chervil, chives, parsley, salad burnet, cress and borage. However, it is seldom that any of us have access to all of these herbs, and so substitutions can be made. The crucial thing is to ensure a good balance of flavours, with the requisite amount of sourness, freshness, bitterness and spice. There is no hard and fast rule about how much of each herb to use, but a rule of thumb is that no one herb should make up more than 30% of the bulk. When possible I try to get a fairly even balance between all of them, but you should adjust to taste and to what is available.

From left to right: borage, wild chervil or cow parsley, salad burnet, wild onion, watercress, sorrel, parsley

Since it is so plentiful in our fields I use wild sorrel (Rumex acetosa), which I suspect is what the authentic recipe calls for, however you can replace this with the more usually grown French or garden sorrel (Rumex scutatus). If neither of these are available you could use young chard or spinach leaves and an extra squeeze or two of lemon juice.

When it is available I use wild chervil instead of cultivated. Otherwise known as cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), it is perfect to pick right now, and can be substituted for garden chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium) in salads or sauces for chicken and fish. If you are an inexperienced forager you must be extremely careful not to mistake poisonous hemlock for cow parsley. Use a good field identification guide (Miles Irving’s The Forager Handbook and Roger Phillips’ Wild Food are invaluable) and, if in doubt, do not pick it.

In place of chives I use wild onion (Allium vineale) from the fields, being careful to pick only the youngest quills, as the older ones are tough. The cress can be replaced with watercress, rocket or even nasturtium leaves, to provide the peppery note. And, from the hedgerows, I have also used the leaves of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), young dandelion leaves and even nettle tops, when the other herbs are hard to come by.

The salad burnet and borage both impart a distinctive cucumber flavour which it is not possible to replicate with other herbs and which is particular to this sauce. When unavailable I have used peeled and finely grated cucumber in their place. Salt it and squeeze the juice from it before incorporating, to prevent it diluting or curdling the sauce.

It is also possible to make up the quantities with more easily available herbs such as dill, fennel, tarragon or mint but, with their pronounced flavours, these should all be used in moderation or they will overwhelm the flavour.

This sauce is also traditionally served with boiled new potatoes and halved hard boiled eggs, or as an accompaniment to boiled beef or poached fish.

Clockwise from top left: salad burnet, watercress, sorrel, parsley, wild onion, borage, wild chervil

Ingredients

150g mixed green herbs

250g sour cream or quark

125g yogurt

2 hard-boiled eggs

3 tablespoons lemon juice

sea salt

7-8 spears of asparagus per person

Serves 4

Method

Wash the herbs. Put them in a salad spinner and then dry on a tea towel or paper towel.

Remove the leaves from the stems.

Discard the stems.

Peel the eggs and put the yolks in a mixing bowl. Coarsely chop the whites and reserve. To the egg yolks add the lemon juice, 2/3 of the herbs, 1/4 teaspoon salt and the yogurt . Liquidise using a hand blender.

Stir the sour cream into the mixture. Add the coarsely chopped egg white. Finally add the remaining finely chopped herbs.

Season with more salt and lemon juice to taste.

If possible allow the sauce to rest in the fridge for an hour or so for the flavours to combine. Allow to come back to room temperature before using.

Gently bend the asparagus spears until they snap. Trim the broken ends. If necessary finely peel the lower sections of the stalks of the outer fibrous layer.

Put water to a depth of 2cm into a lidded sauté pan that is wide enough to take the asparagus in a more or less single layer. Bring to the boil. Put in the asparagus and simmer until tender. For thicker or older spears this may take as long as 5-6 minutes. Fine spears and those just picked will take far less, 2-3 minutes at most. Take the asparagus from the water and spread out on a paper towel on a plate to drain and cool quickly.

Arrange the warm asparagus on plates. Spoon over some of the sauce. Decorate with reserved herb leaves. Eat with fingers.

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Although asparagus only became prized as a culinary vegetable in Britain in the 17th century it was grown, and indeed prized, by the ancients as a medicinal herb and vegetable. The Romans even froze it in the High Alps, with the Emperor Augustus creating the Asparagus Fleet to take the freshly pulled spears to be buried in the snow for later.

The tips, which are the sweetest part and known as the love tips or ‘points d’amour’, are always best when eaten fresh and, though we think nothing of seeing it on the supermarket shelves as an import, there is nothing like eating it in season, right there and then, when the energy of the new season is captured in young spears.

So it is a good feeling to have planted an asparagus bed, as they represent longevity and permanence. Plant one and it will take two to three years to yield, but established crowns can easily crop for a couple of decades if you give them the care they need; namely good drainage, plenty of sunshine and little competition at the root. The roots, which radiate out from a crown in spidery fashion, are shallow, and hoeing is not advisable, so an asparagus bed is also a commitment to hand weeding. You will have to work for your reward.

“…established crowns can easily crop for a couple of decades if you give them the care they need…”

Being a coastal plant, Asparagus officinalis is tolerant of salt, indeed tradition has it that the beds be salted to keep weeds at bay. However, I do not. In truth my bed is far from text book perfect. I have not raised it above the surrounding ground like the carefully drawn diagrams in the books, and the Californian poppies and Shirley poppies have seeded into the open, weed-free ground to become the, admittedly attractive, weeds in the patch.

I winkle the Eschscholzia out where they seed too close to the crowns, but leave a handful, as they like the same conditions and sit brightly beneath the fronds once the asparagus is allowed to grow out after cropping. The few plants that are female pepper themselves with scarlet, pea-sized fruits, which hang in suspension like beads caught in a net as the fronds fade to butter-yellow later in the season. It is a fine but unadvisable association, if playing things by the book is your thing.

Californian poppies provide interest beneath the asparagus ferns later in the season

Californian poppies provide interest beneath the asparagus ferns later in the season

Our first asparagus bed was planted four years ago in the original mixed vegetable and trial garden. The crowns, which are best planted bare-root in the spring, arrived by post and were carefully planted in late April. The soil was manured the previous summer and the crowns laid out on an 18” grid. The books advise two feet between rows, but our slopes are sunny and the ground hearty, so I took the risk with a closer planting.

I opened a trench and fashioned a little mound of soil for each plant to allow the roots to radiate out, down and away from the crown. The trench was then backfilled with the crown just below ground level and marked with a cane to protect the position of the first emerging spears. Over the first year the crowns gather in strength, each frond outreaching the next so that, by the end of the first summer, they are already showing their potential. It is essential to wait before cropping to allow the plants to build up their reserves. I cropped them for the first time last year, but took only a few spears to avoid weakening them. This year, there will be no need to hold back.

Asparagus officinalis ‘Connover’s Colossal’

Asparagus officinalis ‘Connover’s Colossal’

I bought two varieties initially, both male, so I am not sure how I have females in the mix, but no matter. Male plants are more productive and so, according to the rules, the berrying females should be weeded out. ‘Connover’s Colossal’, an old 19th century variety, is a reliably strong cultivar, but ‘Stewart’s Purple’ has been disappointing. It is supposed to be higher yielding than many of the green varieties, but you only really know and understand what a plant’s habits are when you grow it for yourself and, for me, ‘Stewart’s Purple’ doesn’t cut the mustard.

A third of the plants have failed and, although the spears are a beautiful inky purple colour and deliciously sweet, even the plants that have survived have cropped very erratically. They require far too much space to waste on such a meagre harvest. Anthocyanins, which give vegetables and fruit their purple colouring, are valued as antioxidants, but I wouldn’t grow this variety again other than to possibly work it into the herb garden as an ornamental. Here, with moody fronds rising up prettily above chives and purple sage, occasional spears could be harvested and thinly sliced raw into salads.

Asparagus officinalis ‘Stewart’s Purple’

Asparagus officinalis ‘Stewart’s Purple’

There is an associated guilt attached to my original asparagus bed, which comes from the knowledge that the bed could never have been long-term. I always knew the test garden would give way to a new ornamental garden and, over the last couple of years, I have been relocating the vegetable garden to the other side of the house. The diggers are coming in shortly to shape the land for the new garden, but the asparagus bed will remain for one more year, like a boat anchored off shore.

Last spring I planted an F1 variety called ‘Gijnlim’ in the new vegetable garden to pave the way for the hand over from the old bed to the new. Having been selected for its hybrid vigour ‘Gijnlim’ is said to crop within a year, but I am still leaving it this year to build up reserves, mulching the bed with home-made compost before the spears emerge. It won’t be easy to cut my old bed adrift when I have to later in the autumn, but for now we are enjoying the luxury of eating the spears absolutely in season, when the garden is beginning to rush with energy.

“It won’t be easy to cut my old bed adrift when I have to later in the autumn….”

When a bed is up and moving in the spring, you can visit it daily for three weeks or so of harvesting. A sharp knife inserted carefully at the base of a spear and just below ground level is the best way to pick what you need, but be careful not to damage the crown. See it as a surgical exercise and, for best and sweetest results, pick just before you eat. Steam and serve al dente and every mouthful will be worth the commitment.

If you read up about asparagus yields to try and arrive at an ideal number of plants for a bed that suits your needs you get wildly differing advice. An American website says that 24 plants produce enough for a family of four. Big portions I’m guessing, but advice closer to home advises ten to twenty plants for the same number of people. We have sixteen crowns in the new bed and hope that this will be plentiful enough to pick what we need without providing a guilt-inducing glut. I’d have liked for there to be two varieties, so that we have an early cropper and a late, but we have had to draw the line somewhere. There is only so much ground that can be committed to perennial vegetables, even one as delectable as sparrow-grass.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage