In 2014 I was appointed as Garden Advisor to Sissinghurst, which was then under the careful guiding hand of Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith. The role involved an annual walk round the gardens with Troy, acting as a sounding board for his plans to relax the garden and to steer it gently towards its original vision. Over time, and without the owners at the helm, the gardens had been managed to provide their very best for the swell of visitor numbers. I agreed they no longer resembled the gardens of Vita’s writings or her freedom of spirit.

Troy had spent hours immersing himself in Vita’s imaginings, hopes and plans for the gardens, and had written a manifesto that called for a return to a more relaxed and wild, romantic vision closer to Vita and her husband, Harold Nicolson’s, original intentions.

Every time I visited we skirted around Delos, a garden that had originally been built in response to a visit that Harold and Vita had made in 1935 to the ruins of the Greek island of this name in the Cyclades. The garden had been lost, planted in the wrong place, facing north on heavy Wealden clay. It was a place that had come to be more suited to the site and was now part woodland, part lawn with rose beds lining the boundary. The very name felt like an anomaly.

It was in 2018 that Troy asked me if I would work with him and his team to re-imagine the garden. It was daunting making changes to a garden as universally loved as Sissinghurst, but we set to and looked carefully into the history to understand why Harold and Vita had felt compelled to bring something of the ruined island back to Sissinghurst. Troy had sent two members of his team on a field trip to study the vegetation and record the mood of Delos. The time that I too have spent in Greece provided rich inspiration with regard to the planting. We worked carefully with the National Trust historians to test our ideas as they emerged and spent the best part of a year planning. Visiting a local quarry with Nigel Froggatt, the masterful craftsman who built the garden and taking time to mock up the walls so that they felt authentically of the island.

The design made some bold moves that perhaps Harold and Vita did not have the know-how to make at the time. We made light by editing the existing trees back to a Quercus coccifera from the original planting and harvested the sun by battering a number of terraced walls back into the sun to face south. The original axis was reworked to feel like the stepped ruins we had seen in photographs of the garden taken not long after it was made. The terraces that moved away from it became rougher to invoke the hillsides into which the ruins had fallen. We made the old well the centre of the garden, a communal meeting place as it would be in a Greek village and made a seating place amongst columns where Vita had imagined that the blue of the distance could conjure the sea.

I went on my own research trip to workshop the palette of Greek natives with Olivier Filippi at his nursery in the south of France. His knowledge and plant selection is superlative. Some plants were untested in this country, others entirely familiar. On returning to the UK I worked up the planting areas. Goat paths where the aromatic plants would brush your legs and shade-loving drought lovers that would sit happily in the shadow of Judas trees. A mature pomegranate forms a gateway from the White Garden. A fig and the rough twist of cork oaks will, in time, provide height and volume. Aromatic evergreens are already hugging the terraces and perfuming the garden on a hot day and the ephemerals, the annuals that make a Greek spring the spectacle it is, are already beginning to find their niches to make the garden feel lived-in.

Last week, over a year since my last visit for the final planting day in the week before the first lockdown, I returned for the official opening. The garden felt settled and possibly better for the enforced pause of the lockdown and Saffron Prentis, who has been in charge of the garden, has tended it beautifully. The volunteers who man the garden every day have been there to communicate the story behind it and its reimagining.

In 1953, Vita wrote of Delos, ‘This has not been a success so far, but perhaps someday it will come right.’ I know that the changes have not been liked by all who have seen the garden in the flesh or online, but when I returned last week with the planting already looking established after just 18 months, it was possible to see that Vita and Harold’s vision of a Grecian isle transported to the Kentish Weald is once again alive at Sissinghurst and coming right.

_._._._._._._._._._._._._._

When we first started work, Adam Nicolson, Vita and Harold’s grandson, was immensely helpful in facilitating our understanding of the deep-seated cultural motivations of both Harold and Vita to create this garden. At the opening last week he very kindly offered to write a piece giving his perspective on Delos, then and now and I am delighted to share it with you here.

Dan Pearson, Hillside, 8 July 2021

The official opening of the new Delos at Sissinghurst last week is only a beginning. The new cypresses will soon stretch and thicken, the new figs will sprawl and lounge across their neighbouring boulders and walls and the individual plants of Dianthus cruentus will spread and merge into rivers of deep pink, bee-happy colour. A long future awaits this garden, as something to take its place alongside the Purple Border and the White Garden as the brightest of stars in the Sissinghurst constellation.

It has been a long time coming. Throughout my childhood at Sissinghurst, we always knew that in the 1930s Vita and Harold had wanted to make a Greek garden in this most unpromising of clay-wet, north-facing and very very Kentish corners. They attempted it, assembling some of the Elizabethan stones they found lying there into stepped platforms that vaguely recalled temple foundations in the drought of the Aegean. But the soil was wrong, the site was wrong and over the years a series of efforts were made to redeem it. My father removed all those stones to make the foundations of his gazebo; a very American grove of birch-like magnolias was planted to preside over a carpet of scillas and chionodoxias through which a few peonies poked their heads; new brick paths were laid. Delos had essentially been lost.

It has now been found and in the richest possible way: the silhouette of a flowery garrigue billows up in front of big country rocks; rubble-terrace walls firm up into what might be the foundations of buildings along the central street of this forgotten city; the half columns of an abandoned temple stand on the slope above.

It is pure theatre, as it was always intended to be, entirely dependent on a big, hidden drainage system and an especially free-running soil, with plenty of grit and crushed brick to make the Mediterranean plants feel at home. Clay is nowhere to be seen.

There is one element that reaches further back into history than the dreams of the 1930s: three cylindrical Greek marble altars, originally carved in the 3rd or 4th century BC, decorated around their waists with swags of grape, pomegranate and myrtle suspended between garlanded bull-heads — boukrania—which now stand at key intervals along the central street of the garden. Perhaps almost unnoticed among the blaze of life and colour around them, these altars remain the core of the garden and its meaning. They are the reason it is called Delos, as they came originally from that famous island in the Cyclades, sacred to Apollo, and represent an element of the story that was undoubtedly close to Harold Nicolson’s heart.

His mother’s grandfather was Commodore William Gawen Rowan Hamilton, a naval commander in the first years of the nineteenth century, a heroic and romantic figure and passionate Philhellene, who spent the years from 1820 onwards in the eastern Mediterranean, winning the title of ‘Liberator of Greece’ by protecting the Greek rebels against the Turks and spending much of his private fortune in their cause. There is still a street in Athens named after him in gratitude.

From time to time during his cruises attacking pirates and fending off the Turk, he would land on an island or a piece of the Turkish-occupied mainland and quietly liberate an antiquity or two, sending them back to his liberal father-in-law in Ireland, Major-General Sir George Cockburn, a flamboyant antiquary who had made a collection of Greek statuary at Shanganagh, his castle outside Dublin.

These Delian altars arrived there in the late 1820s, dripping with Greek-loving, liberty-loving significance, and when in 1832 the British government promised in the Great Reform Bill to democratise the corrupt state of British politics, Sir George erected them in a column to Liberty outside his front door. They stood there for six long years, during which the government entirely failed to reform the basis of British politics, and in rage and frustration, Cockburn had carved on the base of the monument the grand reproach: ALAS, TO THIS DATE A HUMBUG.

In 1936, when the contents of Shanganagh were sold up, Harold Nicolson bought the elements of his great-great-grandfather’s column and had them transported to Sissinghurst. The HUMBUG base and one altar is still in the orchard; the three others are in Dan’s new Delos, still in my mind radiating everything which that long, Rowan-Hamilton-Nicolson tradition valued most: a love of liberty; an internationalist, pan-European vision; a cosmopolitan grasp of and engagement with world culture; and a treasuring of those dry, beautiful, ruin-scattered landscapes sacred to Apollo which this Kentish garden now recalls.

Adam Nicolson, Perch Hill, 3 July 2021

Photographs | Eva Nemeth

Published 10 July 2021

Three years ago, Troy Scott-Smith invited me to become a Garden Advisor for the garden at Sissinghurst. It was a role I was happy to explore, for I have known the garden for years as a visitor, but there is nothing like getting to know a place better from behind the scenes and through the people that work there.

Anyone who owns or gardens a garden knows all too well that feeling of only seeing what needs doing. Sometimes it is hard to focus on the achievements, the long view or to simply take stock and see what is happening in the here and now. My annual meetings with Troy take place in a different season every year, with notebooks and an open brief to walk and talk and ponder. This year I made my visit in late March, a good time to evaluate a garden while the structure is still visible.

A second eye from an outsider is often exactly what is needed and we have cultivated an openness in the discussion, where opinions may count here but not there, and where the shared mission is to get to the essence of things. For me, this is a complete luxury, as I am free of the responsibility I have in my role in the design studio and can look without having to provide more than an honest opinion.

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

Head Gardener, Troy Scott-Smith

By way of introduction Troy had sent me his manifesto before my first visit. When he applied for the role as Head Gardener he talked openly of the need for change and, to the credit of the National Trust, they employed him to implement this vision. He absolutely did not see this as change for change’s sake, but a means of recapturing the potent sense of place that Vita Sackville-West celebrated in her writing about the garden that she and Harold Nicolson had made at Sissinghurst Castle; a garden inextricably linked to the buildings it surrounded and, in turn, the Kentish farmland and countryside that swept up to its walls.

Troy saw the need for the place to be unlocked again from the rigour that had become the way that people came to know the garden after the death of Vita and Harold in the 1960’s. A challenge perhaps for the most famous garden in the country but, for one with such good bones, a new era of excitement.

The Top Courtyard

The Top Courtyard

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

Beyond the wall of the Top Courtyard is Delos

The White Garden

The White Garden

The Orchard

The Orchard

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

The Cottage Garden with topiary yews (left) and the Rondel (right) with the Rose Garden to the right. The Lime Walk can be seen running to the left of the exit at the top of the Rondel.

I expect that there are very few good gardens that are the product of one vision. Gardens are places where skills come together and, indeed, where they work in combination to make the whole altogether stronger. Vita and Harold’s relationship was a perfect example. He with his architectural mind providing the structure and she, the romantic, the counterpoint of informality. Her writings talk of a place that was, first and foremost, lived in by its owners and where ideas and experiments did not demand year-round perfection. However, the garden then did not have the pressures it has now with up to 200,000 visitors a year. Mulleins breaking into the paths could be negotiated and roses reaching beyond their allocated space were free to reign.

Vita wrote well about her gardening experiences and possessed a powerful vision, but she was not a professional gardener. She was learning as she evolved the garden and, like all of us, her mistakes and failures were probably as numerous as her successes. Clambering roses overwhelmed the apple trees to bring them down where their vigour wasn’t matched, and some areas of the garden were simply allowed to recede into the background when out of season. There were bold and visionary moves, such as the tapestry of polyanthus in the Nuttery that would ultimately fail to disease and need rethinking.

When the National Trust took over in 1967, five year’s after Vita’s death, an inevitable tightening up eventually saw the garden reach extraordinary horticultural heights in the hands of Pam Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger who worked with Vita from 1959 until she died, but went on to make the garden their own during their 30 year tenure as joint head gardeners. Pam and Sibylle’s prowess with plants was a large part of what brought visitors to Sissinghurst in their droves in the 1970’s and ’80’s, securing its place as one of the most influential gardens in the world. The way the garden became was ultimately driven by the need to provide for increasing numbers of visitors and, in so doing, the intimate sense of place was slowly and gradually altered.

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

Troy and Dan in the Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

The Lime Walk

In the Rose Garden

In the Rose Garden

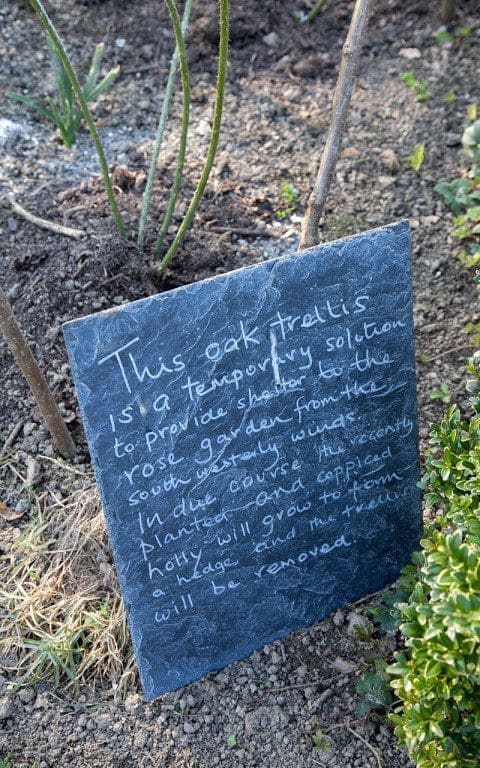

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

New oak trellis in the Rose Garden

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

Yew hedges are gradually being reconditioned with hard pruning

I have known Sissinghurst since I was a child. My father and I would visit every summer and walk its enclosures with notebooks in hand. I remember very distinctly the feeling of awe and then panic fused with disappointment that we would simply never be able to garden to this level of perfection. So we would drive on determinedly to Great Dixter to take the antidote of a garden living and breathing its owner and not attempting to garden with belt and braces. Even when the blueprint is strong gardens can easily assume a different character, for a garden is really the gardener.

And now Troy is slowly and gently making changes. He has turned the lawns at the approach into meadow and reinstated an old cart pond. There is a new hoggin entrance and there is talk of returning some of the brick and stone paths in the gardens to grass. If they wear, people will be redirected until the grass recovers, to preserve the calm and intimacy of the softer surface.

Roses that were tightly trained against the walls were given a couple of years off to reach away from their constraints. New apple trees have replaced old and the cigar-shaped yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape, as they were in Vita’s day. The Little North Garden (formerly the Phlox Garden) was for years made inaccessible from the White Garden after the steps were removed in 1969. It has been reconnected with new steps which will provide another way out when the White Garden is at its peak and crowded. And Troy is planning on re-instating the phlox that once grew there in Vita’s time and after which she named it.

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

The yews in the Top Courtyard are being allowed to grow out into a looser shape as they were in Vita’s day

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

Discussing Troy’s planting plans for the Little North Garden. The new stone steps lead up to the White Garden.

The White Garden. The Little North Garden is reached through the arch in the boundary wall.

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

Dan and Troy discuss recent new additions to the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

A newly planted olive in the White Garden

For years the Kentish Weald was the driving force and counterpoint to the formality of the garden and its enclosures, so we have talked of taking pressure off the garden and of making it less introverted, opening it up again to the land around it. The Nuttery has been enlarged, with new coppice hazels, a softer secondary path and a permeable fence boundary to the fields beyond. By removing the later addition of the hedge along the Nuttery, the field and the lake it flanks instantly provide a visual decompression. There is now talk of allowing people into the meadow and down to the lake so that, when the garden is busy, it provides an overspill area. After many years without them, Troy is also planning to reinstate Vita’s massed plantings of polyanthus in some areas.

The Nuttery

The Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

Original stone path in the Nuttery

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

New soft path in the Nuttery, with additional coppice hazel and visually permeable split chestnut fencing

Last year, Joshua Sparkes, one of the enthusiastic young gardeners working with Troy, won a scholarship to visit Delos, the inspiration for one of the garden areas that has lost its way. Vita and Harold had been inspired by the Greek island and had strewn the area beyond the Top Courtyard with a small number of artefacts and stone walls to conjure a Greek hillside. Facing north and with exposure to the winds from across the fields, the site was not the ideal place to try such an experiment.

Later incarnations saw the garden protected on the windward side with a hedge of Pemberton roses and a canopy of magnolias took over to provide more shade, which subsequently saw the garden become home to primarily woodland plants. However, Troy has a little grove of cork oaks waiting in the nursery and Joshua’s research has identified a number of Greek natives to bring out the spirit of the place again. It may not be exactly as Vita and Harold had intended, but they wouldn’t have stood still either. As gardeners I have the feeling they would have embraced change and all the excitement and energy that comes with it.

Delos

Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Spring planting in Delos

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage