ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

Life has begun to stir, the snowdrops suddenly visible and lighting the gloom. Over the last ten years I have been adding to a ribbon that is designed to draw us out into the landscape. It starts in the hedges close to the house and skips down the ditch in a stop-start rhythm where I have found the places that they like to be. Not too wet and with just enough shadow to keep the grass down once they have come into leaf and do their bulking. They reappear then down by the stream to run its length and ensure we walk our stretch whilst we can still get to the water in winter. The gesture demands generosity and commitment to adding to the trail, like a conversation you come back to, but is never really done.

We need to think expansively beyond the curtilage of the garden, where the land takes over and we could never nor want to control all that we see. Although the touch by necessity needs to be light in these wilder places, it should also feel generous. Not in a conspicuous way, but right because you have found a niche and then followed it. The big moves always start with a small one. Finding the place that a plant likes to be and understanding why and then going with it.

Working at scale in these wilder places demands both patience and persistence. Neither feel forced or hard won when the mother plants begin to seed. The primrose splits from five years ago came from a colony that was hiding amongst a cage of brambles. We fenced the ditch to keep out the livestock, cut away the brambles and the primroses proliferated on the hummocky slopes where each had its little microclimate. The splits – taken early in April not long after the primroses had peaked – were found a similar position and, where we hit the sweet spot, they are showing their happiness there in seedlings. The seedlings slowly erase your hand. The regular rhythm you try to avoid when planting, but cannot help but read when you look back on what you have done. The seedlings skip a beat, their seed taken to a new place by ants. The ones that come through feel right for having found their own place.

By its very nature my role as the ‘gardener’ of these natural processes cannot help but want for a little more. So where splits have proved to be too slow – the mother plants taking time to bulk – I have taken to collecting seed. This is ripe in June, but you have to watch carefully then as the plants are often consumed in the shadow of summer vegetation. The seed is best sown fresh or it begins to enter a period of dormancy that is hard to break. Fresh seed germinates erratically, some in the late summer and over autumn, but the majority in the spring after it has had time for the frost to do its work.

I sow three or four plug trays each year (between 300-400 plants) casting the seed over the tray and then top-dressing with sharp grit to protect it. Sowing annually means that I have a relay of seedlings on the go. Seedlings are left in the trays for 18 months and planted out just about now, when there is time for their early growth to get ahead of the competition. This year the seedlings are going into the steep banks up behind the house, where the sheep have opened up the ground with heavy grazing and poaching. The slope is south-facing and primroses love to bask in early sunshine. Here the bees find them early too. The summer cover of the grassland that rises up around them will keep them in the shade they like later.

Also in mass production and destined for the wilder places are some locally sourced bluebells grown from seed. This is not bluebell country, their niche here being on the heaviest clay in the woods and not where it is too rich and competitive. I have been studying our ground to find the place where I imagine they might thrive, even just in pockets so that we have some pools of blue in the coppice.

Then there are the bulbs that are too expensive to buy in bulk and that I hanker for en masse. Camassia leichtlinii originally bought as ‘Amethyst Strain’ from Avon Bulbs and now renamed Avon Stellar Hybrids, are destined for the ditch. Well-named for their colour range of mauves and lavenders, their propensity to rampant seeding in the open ground of the garden will be mediated by the competition of grass. Tulipa sprengeri (at a prohibitive £5 a bulb) comes easily from seed if you are prepared to wait, as does the pale-flowered form of the native early winter aconite, Eranthis hyemalis ‘Schwefelglanz’. I plan for sheets of this butter-yellow form one day, in the places that are too damp for the snowdrops, but on the same trail and flowering with them in January. Though the wait is usually five years to flower for most of the bulbs, the beauty of sowing every year means that there is always a tray finishing the relay and ready to join the land of plenty.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 January 2021

With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

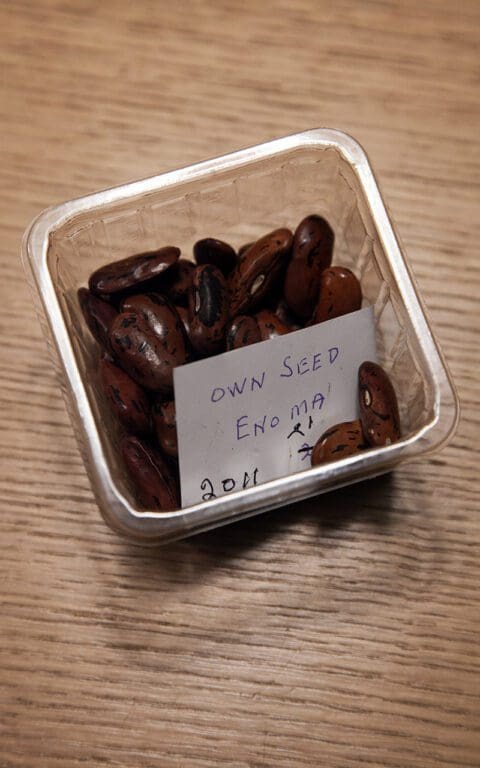

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast. I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing. The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

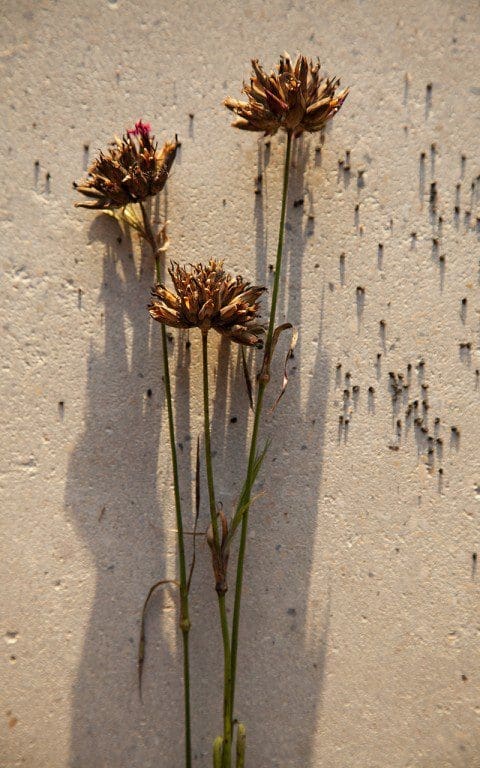

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018 A year ago now, and with the prospect of planting up the final part of the garden in the autumn, I wanted to add some variety to the range of plants that was available from my favourite nurseries. So, I set about sowing some additions from seed, to feel that I’d grown them from the very beginning and to understand them fully. Bupleurum perfoliatum and Aquilegia longissima were needed in quantity to weave into the new planting and to jump around, as if self-sown. It was also good to revisit plants that have become hard to obtain, such as Aconitum vulparia, a creamy wolfbane from Russia which I’d grown as a teenager and had a hankering for again.

The success stories of the plants I knew and understood were reassuring. Those that I didn’t, vexing but fascinating nevertheless. It is a mistake to throw out a pot of seed that hasn’t germinated within a year, because it may simply be waiting for its moment. The Viola odorata ‘Sulphurea’ needed the freeze of a winter to break dormancy and I learned by chance that Agastache nepetoides needs light to germinate, and so should be surface sown. My usual top dressing of horticultural grit, used to prevent moss and as a slug repellent, was washed from the sides of a pot by a leaky rose, opening up a window of opportunity, the seed germinating there and there only to burn this fact into my memory. Some seed may have been too old by the time it was sown, with very poor germination on the Anemone rivularis, but the small numbers mean that the plants that made it are that much more precious. Although the value of seed-raised plants increases when you have tended them from their vulnerable beginnings, it is also good to feel that you can be generous, because some plants are just so easy.

Having grown the biennial Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ the year before, the first plants had all flowered and seeded so an interim generation was needed to set up a continuity. The large, flat seed threw out fat cotyledons in a matter of days and the distinctive purple-tinged foliage was already there in the first true leaves. Where the perennial Anemone rivularis took their time to build up strength for the life ahead of them and had to be watched because they were so slow, the pioneering nature of the Lunaria means that you have to keep up to make the most of the growing season. The seedlings were potted on into 9cm pots as soon as the first true leaf was properly formed, handling the seedlings only by their cotyledons and never their vulnerable stems. With the new opportunity of their own space, they worked up a rosette last summer that was hearty enough to plant in the autumn and bolt the early spring of flower a year after sowing.

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora with Paeonia delavayi

Of the short-lived perennials I’ve used to provide for me early on in the life of the establishing garden, the Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora have been good to revisit. The white sweet rocket was a plant of my childhood garden, where it had sprung from the clearances of brambles like a phoenix from the ashes. Rising up fast with the cow parsley and easily as tall, its early flower bridges late spring and early summer. I have not had room to grow it for a while, because its ephemeral nature this early in the season can easily smother neighbours, to leave a summer gap when you cut it back to the rosette once it’s done. Let it seed and you will find a rash of youngsters, for it is also a pioneer that sees seedlings bulking up over summer in readiness to conquer new ground the following spring. This eagerness can easily be tapped, and it is good to leave a couple of limbs to go to seed as the plants are only good for two or three years before they exhaust themselves.

Sweet Rocket are adaptable to both an open position or to dappled shade, but the advantage of a cool position is that they grow less vigorously and take less ground. Mine were interspersed randomly in the planting to perfume the steps that descend to the studio and their distinctive, sweet scent is held in the stiller air caught behind the building. Bulking up fast once they were released from their pots, they have provided me with a rush of new life that has outstripped but complemented their slower growing neighbours. Seed-raised plants are more often variable and this is one of the joys of growing your own. Of the twenty or so plants, I must have almost as many different variants.

There is a blowsy head girl, brighter and showier than its neighbours and probably the one you would choose as a complement to a Chelsea rose garden, although she leans and topples under her own weight of flower. There is a perfectly behaved plant nearby. Just as white, but smaller and quieter and perfectly happy to stand upright without staking. This is probably the one that you would propagate from spring cuttings if you wanted something showy and reliable. My favourites have a wilder feel though; a grey-pink cast to some and more open flower panicles to others that provides the space I am so keen on and a lightness in the planting that feels less dominant. Head Girl has been used for cutting and will come out when I cut the plants down to prevent it from seeding and allow my slower-growing perennials around them the room they need to fill out later in the summer. Though the Actaea, the Zizia and the peonies are destined to provide a more certain future, the fast sweet rocket will always be just that.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photos: Huw Morgan

Published 26 May 2018

My childhood interest in cooking was first encouraged by my maternal grandmother. When I was about 7 she taught me how to make scrambled eggs on toast. Then, during our summer holidays on the Gower, she followed this with instruction in the cakes from her pantheon of Welsh standards – Bara Brith, Welsh Cakes and pikelets – and, from Marguerite Patten’s ubiquitous wartime cookbooks, she introduced me to the classics – scones, jam tarts, rock cakes and Victoria sponge cake.

When we started to travel further afield to Brittany for our holidays I was always drawn to sample the baked goods; proper butter croissants and pains au chocolat at the ferry port, quite unlike the frozen Pilsbury Dough ones I had eaten at home, palmiers, millefeuilles and éclairs from the patisserie near the camp site, and from the markets we would buy buttery Gateau Breton, custardy apple cake and indulgent kouign-amann. Brought up on Cadbury’s Mini Rolls and Mr. Kipling’s Fondant Fancies these cakes were so exotic to me that I would return home wanting to try and make them.

At 17 I went to Austria on a student exchange and here I discovered a whole other world of cake; Sacher Torte, Linzer Torte, Apfelstrudel, Marillenknödel and Zwetschgenknödel (potato dumplings stuffed with whole apricots or plums respectively) and my first proper baked cheesecake studded with juicy raisins, which was a far cry from the chalky refrigerated ones with their gelatinous fruit toppings that I was familiar with. However, the cake that lodges most firmly in my memory is the Mohnkuchen I ordered in a Café-Konditorei in Salzburg.

When I saw it on the menu I asked my host family what Mohn was. When they explained that they were poppy seeds this seemed to me so sophisticated and unusual an ingredient for a cake that, with my awkward teenage desire to appear sophisticated and unusual, I ordered it. When it arrived at the table my suspicions were confirmed by its rather austere appearance, and its minimal crust of translucent water icing. It was the early ‘80’s and I thought my grey cake was unutterably chic and I was (perhaps rather too) pleased with myself for having ordered it. My palate was then educated by the discovery that this cake was primarily a textural experience; the somewhat challenging gritty feeling in the mouth and the ephemeral bitterness of the seeds making me sure that this was a cake for grown-ups, not children. An acquired taste.

The recipe below is an amalgamation of several recipes I have tried in an attempt to reproduce that first piece of Mohnkuchen. The flavouring should be subtle, not too heavy with either vanilla or lemon, so that the delicate flavour of the poppy seeds comes through. It is essential to grind the seeds in either a mortar and pestle or a clean coffee or spice grinder as, from experience, the blade of an electric food mixer is not up to the job. You will need to grind the amount of seed required for this cake in batches. You want to achieve the texture of wet sand, with a good balance of ground and whole seeds. When we have a good opium poppy harvest I take pleasure in using our own seed but, with the amounts called for, you need to have quite a poppy patch to produce enough.

I use a richer yogurt icing here, which makes this more of a special occasion cake, but it is still very good with the traditional light water icing which, in Austria, is sometimes flavoured with rum for a truly grown-up cake.

Ground poppy seeds

Ground poppy seeds

Serves 12

Ingredients

CAKE

150g unsalted butter

150g caster sugar

5 large eggs, separated

75g plain flour, preferably Italian 00

75g ground almonds

180g poppy seeds, ground

120ml plain yogurt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Zest of half a small lemon, finely grated

ICING

6 tablespoons natural yogurt

Juice of half a lemon

100g icing sugar

Method

Preheat the oven to 180°C.

Butter a 22cm round cake tin and line with baking parchment.

Beat the butter with the sugar and vanilla extract until pale and fluffy. Add the egg yolks one at a time. Beat well to incorporate fully before adding the next one. If the batter shows any sign of curdling add a teaspoon of the flour and beat until smooth.

Stir in the yogurt until well combined. Then fold in the flour, ground almonds, poppy seeds and lemon zest.

Beat the egg whites into soft peaks. Gently fold these into the cake batter a little at a time until fully incorporated.

Pour the batter into the prepared cake tin and bake for 40-45 minutes, until a skewer inserted comes out with just a few crumbs attached.

Allow to cool in the tin for 20 minutes, then remove from the tin, take off the baking parchment and put on a cooling rack until cold.

To make the icing, in a small bowl stir together the yogurt, lemon juice and icing sugar until smooth. Pour onto the cake and spread out with a palette knife, encouraging it to flow over the edges. Decorate with poppy seeds.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

We have had a remarkable fortnight. August at its best with heat in the sun and long cloudless days. Cracks have opened up in the ground that are large enough to slide my fingers into and the garden has responded accordingly with fruit ripening and plants racing to set seed. It has been the perfect time to gather, with a daily vigil to check on ripening and harvesting just as the seed is ready to disperse. It is a yearly ritual, which I can trace back over thirty years to my black opium poppies. I may have missed a year or two of scattering them onto new ground to ensure that I have them the following year, but I have always had their seed in store, just in case. The seed is a currency of sorts and I can always depend upon the next generation if I have some in my pocket. Saving and sowing seed is rewarding on many levels. First, it is free, and mostly plentiful. A pinch goes a long way, but sometimes you need more than a pinch to make an impression. Secondly, raising plants from seed gives you a full and rounded understanding of how a plant develops and what it needs at each of its stages of life to thrive. A seed-raised plant has a different value, for you have not skipped a step. It will have been in your care from the get-go and may also come with associated stories that trace directly back to its provenance; what it grew with and where, or who passed the seed on and why.

The seed of Stipa barbata is like the point of a dart and drills itself into the soil vertically when the long, silvery awn twists and contracts above it

Seed-raised plants are prone to variability and just occasionally you might find that a form has something superior to its parent: more vigour, a difference in flower colour or the potential of resistance to disease. Ash-dieback is an issue that we are all dreading as it works its way across the country, but there is surely hope in the fact that ash are such prolific seeders, that maybe there will be a seedling, or a percentage of seedlings, that are naturally resistant.

Not all seed comes true and this has its advantages as well as its disappointments. I keep my Tagetes patula and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ at opposite ends of the kitchen garden, as they are notoriously promiscuous. If they cross-pollinate the deep, velvet-red of the ‘Cinnabar’ will be tainted, its crosses in the next generation slashed with yellow, with neither the electric tangerine colour of the pure species nor the richness of the named hybrid. It is good to keep them pure.

The seed of Stipa barbata is like the point of a dart and drills itself into the soil vertically when the long, silvery awn twists and contracts above it

Seed-raised plants are prone to variability and just occasionally you might find that a form has something superior to its parent: more vigour, a difference in flower colour or the potential of resistance to disease. Ash-dieback is an issue that we are all dreading as it works its way across the country, but there is surely hope in the fact that ash are such prolific seeders, that maybe there will be a seedling, or a percentage of seedlings, that are naturally resistant.

Not all seed comes true and this has its advantages as well as its disappointments. I keep my Tagetes patula and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ at opposite ends of the kitchen garden, as they are notoriously promiscuous. If they cross-pollinate the deep, velvet-red of the ‘Cinnabar’ will be tainted, its crosses in the next generation slashed with yellow, with neither the electric tangerine colour of the pure species nor the richness of the named hybrid. It is good to keep them pure.

Tagetes patula (left) and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (right)

In contrast the range of amethyst colours found in Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ are the delightful result of natural variance, coming in the darkest blue-purple and fading through grey-lilac and pink to off-white. For the last couple of years I have been harvesting seed from mine to build up stocks. The seed is prolific and I have broadcast some on the wildflower banks below the kitchen garden in the hope that they will find a window and establish in the sward. I have also sown a pot full of seed for a more controlled result. When sown fresh they come easily the following spring. A pot sown each year should provide me with the quantities that I need to make an impression. After sowing they should take three to four years to flower and it will be exciting to see the natural variability in the seedlings.

Tagetes patula (left) and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (right)

In contrast the range of amethyst colours found in Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ are the delightful result of natural variance, coming in the darkest blue-purple and fading through grey-lilac and pink to off-white. For the last couple of years I have been harvesting seed from mine to build up stocks. The seed is prolific and I have broadcast some on the wildflower banks below the kitchen garden in the hope that they will find a window and establish in the sward. I have also sown a pot full of seed for a more controlled result. When sown fresh they come easily the following spring. A pot sown each year should provide me with the quantities that I need to make an impression. After sowing they should take three to four years to flower and it will be exciting to see the natural variability in the seedlings.

Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ showing the natural colour variation in the flowers

Self-sown seedlings are an indicator that you have found a place that suits a plant. This is my ultimate goal in the garden here: to work with the conditions and what the plants favour and for self-seeding to create a ‘blur’ in some of the plantings that allows them to take on their own direction.

Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ showing the natural colour variation in the flowers

Self-sown seedlings are an indicator that you have found a place that suits a plant. This is my ultimate goal in the garden here: to work with the conditions and what the plants favour and for self-seeding to create a ‘blur’ in some of the plantings that allows them to take on their own direction.

Seed collected this summer

The seed gathering started last month, each new collection stored in a reserve of pie boxes which make the perfect receptacles. The boxes are left open on a sunny windowsill until the seed is thoroughly dry and then labelled for clarity. Not all seed is for keeping. Umbellifers, for instance, and plants from the family Ranunculaceae are best sown fresh as the seed degrades rapidly. Sown now, and depending upon the species, they will sit in their pots until spring and have their dormancy broken by the stratification of frost. Peonies may take up to two years to germinate. The first year will see roots forming and nothing above ground, the second spring will give you the first leaves, so sometimes patience is important. Other seed such as scabious and Succisa come up almost immediately, so that they are past the seedling stage in order to overwinter as youngsters and get away quickly in the spring.

Seed collected this summer

The seed gathering started last month, each new collection stored in a reserve of pie boxes which make the perfect receptacles. The boxes are left open on a sunny windowsill until the seed is thoroughly dry and then labelled for clarity. Not all seed is for keeping. Umbellifers, for instance, and plants from the family Ranunculaceae are best sown fresh as the seed degrades rapidly. Sown now, and depending upon the species, they will sit in their pots until spring and have their dormancy broken by the stratification of frost. Peonies may take up to two years to germinate. The first year will see roots forming and nothing above ground, the second spring will give you the first leaves, so sometimes patience is important. Other seed such as scabious and Succisa come up almost immediately, so that they are past the seedling stage in order to overwinter as youngsters and get away quickly in the spring.

Seed of umbellifers, such as Opopanax chironium, must be sown fresh

I like to sow in a gritty mix for maximum drainage and find that if the seedlings have to search for moisture they develop a better root system. Seed is scattered as lightly as possible across the surface so that the seedlings have room to develop their first true leaves before transplanting. I like to top-dress the seed with horticultural grit, again for drainage and also the advantage of protecting the seedlings from the soft underbellies of slugs and snails. The pots are stored in the controlled environment of the cold-frame where I can keep an eye on watering, and so that they do not lie wet in winter. Seed for keeping, such as the annual tagetes, will be kept dry in Tupperware in the back of the fridge to slow their degradation and brought to life again next spring with the summer stretching ahead of them.

Seed of umbellifers, such as Opopanax chironium, must be sown fresh

I like to sow in a gritty mix for maximum drainage and find that if the seedlings have to search for moisture they develop a better root system. Seed is scattered as lightly as possible across the surface so that the seedlings have room to develop their first true leaves before transplanting. I like to top-dress the seed with horticultural grit, again for drainage and also the advantage of protecting the seedlings from the soft underbellies of slugs and snails. The pots are stored in the controlled environment of the cold-frame where I can keep an eye on watering, and so that they do not lie wet in winter. Seed for keeping, such as the annual tagetes, will be kept dry in Tupperware in the back of the fridge to slow their degradation and brought to life again next spring with the summer stretching ahead of them.

The first of this year’s sowings ready for the cold-frame

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage

The first of this year’s sowings ready for the cold-frame

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage