ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

Last week we passed the half way point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox; the Gaelic celebration of Imbolc. Here in the garden there is a notable shift from slumber. Bright rosettes amongst the leaf litter, looking determined and suddenly visible. Newly green amongst the darkness of foliage from last year, which is daily being pulled to earth by the earthworms and mouldering. The cycle making way and the old providing for the new as the nights become shorter.

In the garden, it was the witch hazel which were the first to stir. I grew them in pots when we were living in Peckham and were pushed for space and needy for more. They were brought up close to the house where their winter filaments could be given close and regular examination. They grew surprisingly well considering their confinement, to the point of outgrowing their summer holding ground in the shadows at the end. I passed them on as they outgrew us. ‘Jelena’ was big enough to warrant the hire of a white van and driver to take it to Nigel Slater in his north London garden. A number went to clients and the remainder came with us in an ark of the best plants to live with us here.

Our sunny hillside with its desiccating breeze does not provide the ideal conditions for hamamelis. In an ideal world they would go down in the hollows, where the air is still and the cool shadows finger from the wood on the other side of the stream. Although they are modest and do bear a likeness to hazel in summer, their winter value is bright and otherworldly. Too bright and too ornamental to sit in the company of natives.

As a highlight of these dark months, the witch hazels are worthy of the pockets of shelter up in the garden. Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ claims one such position alongside the old milking barn, where the west-facing aspect protects it from the sun for more than half the day when it is at its height. On a still day a delicious, zesty perfume describes a definable place that you encounter as you move alongside the barn. It makes your mouth water. The colour of ‘Gingerbread’ is well named. It is hot and spicy, but dims after a couple of days perfuming the mantlepiece.

The plant must be about fifteen years old, given its time in London and the early years here still confined to its pot. Though slow to settle in, the limbs now reach out widely and provide me with a little microclimate. Its branches offering a shadowy place beneath for lime green hellebores and paris and a climbing frame for scarlet Tropaeolum speciosum, which covers for the witch hazel’s modesty come the summer.

The willows come once the witch hazel are already in bloom, their neatly fitting sheaths thrown aside as the pussies begin to swell. Salix daphnoides ‘Aglaia’ with dark mahogany stems and silver-white catkins sits a walk away as an eyecatcher down in the ditch. Closer in Salix gracilistyla, acts as guardian to either side of the lower garden gate. Not so commonly available as the black form, S. gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’, or the pink-pussied S. g. ‘Mount Aso’, I love the straight species for the delicacy of silvery-grey. Like the fur of a rabbit, it is impossible not to touch as you move to and fro and I have let the branches reach in from either side to encourage this interaction. As the flowers go over, the bushes will be hard pruned to a framework in early April to keep the plants within bounds so you can see over them and still have the view.

Just a week after the winter mid-way we find ourselves at peak snowdrop. Those in the warmest positions where they bask in winter sunshine have been out already for a fortnight, but right now is the week of the majority, at their most pristine and poised. What the Japanese call shun, the moment when a plant or crop is full of its vital and optimum energy.

I have fallen under the spell, for the snowdrop’s solitary presence is a tonic when you are pining for life. Their ability to draw you out into the winter and make it a place that is finer for their presence is why, perhaps, when you do find yourself spellbound, you begin to want for more. That is another story altogether. One which I will share with you another year when I feel I know more, but suffice to say I have begun a collection of specials. All three here (each named after characters from Greek mythology) are readily available for being reliably good plants and you can buy them easily enough in-the-green, as bare root bulbs from Beth Chatto’s for planting out now. ‘Galatea’ was first given to me by our friend Tania. The ‘goddess of calm seas’ is a fine reference, but the long pedicel suspends the flower in the arc of a fishing rod, so if there is a breeze, they are wonderfully mobile. In the warmth or on a bright day, they fling their petals back in a joyous movement to expose their skirts to the bees.

Though the doubles tend to last longer in flower, they are not always my favourites. The bees favour them less because they are harder to pollinate and the simplicity of the flower can often be lost in frilled petticoats. Not these two, which both have an interior that is beautifully tailored. ‘Hippolyta’, daughter of the Queen of the Amazons, is the shorter and more upright of the two with a fullness and roundness to the flower which is distinctive from a distance. ‘Dionysus’ has both poise and height, though it is good to plant the doubles on a slope so that you can admire their undergarments. Named after the god of wine (and ritual madness) I am happy to be swept along in a little obsession and midwinter mania.

Words: Dan Pearson | Flowers & Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 February 2021

There was a heavy frost this morning and we were suspended for a while in a luminous mist. The wintry sun pushed through by lunchtime, the melt drip-dripping and the colour of thaw returning as the unification of freeze receded. Undeterred the Coronilla valentina subsp. glauca ‘Citrina’ emerged unscathed, liberating their sweet honey perfume in the sun.

We went on a hunt for flower to see what there might be left for the first winter mantlepiece. The pickings, now rarefied, feel held in a season beyond their natural life. A rogue Lunaria annua ‘Chedglow’ misfiring, but welcome for the reminder of the hot violet which you have to imagine as you move the seedlings around to where you want them to be in the autumn. My original plants, a dozen grown from seed two years ago, are now gone. Last year’s pennies threw down enough seed immediately beneath to need thinning and the transplants allowed me to spread a new colony along the lower slopes of the garden. Being biennial, it is good to have two generations on the go so that there will always be a few that come to flowe,r but enough to run an undercurrent of lustrously dark foliage in winter. It is never better than now, revealed again when most of its companions have retreated below ground.

The reach of the Geranium sanguineum ‘Tiny Monster’ is now pulling back to leave a shadow where it took the ground in the summer. It has been flowering since April, brightly and undeterred by all weathers. This larger than life selection of our native Bloody Cranesbill shows no signs of stopping as the clumps steadily expand. It is a slow creep, but a sure one. Short in stature at no more than a foot, you have to team it carefully if it is not to overwhelm its neighbours. We also have the true native G. sanguineum, grown from seed collected from the sand dunes on the Gower peninsula in Wales, and teamed with Rosa spinosissima from the same seed gathering. The two make a fine match, the geranium scrambling through the thorns of the thicket rose.

The pink Hesperantha was a gift from neighbours who gave us a mixed bag of corms including the earlier flowering H. coccinea ‘Major’. This hot red cousin flowers when there is heat in the sun, but gives way to this delicate shell-pink form (which we think is most likely to be ‘Mrs Hegarty’) as the days cool in October. I am not a fan of delicate pinks, preferring a pink with a punch, but it is hard not to love this one when it appears. I like it for standing alone at this time of year and for not having to compete for being so very late in the season. In terms of where they like to grow though, Hesperantha hail from open marshy ground in South Africa so you have to find them a retentive position with plenty of light to reach their basal foliage. I have them on the sunny side of Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ which they come with and then go beyond.

Equally hardy, and one of the longest-flowering plants in the garden, is the Scabiosa columbaria subsp. ochroleuca whose delicate pinpricks of lemon yellow are held high on wiry stems and are still enlivening the skeletons of Panicum and Deschampsia that are now collapsing around them. Even now they are a magnet for the hardiest bees and the odd peacock butterfly that ventures out in the weakening winter sun before hibernating.

Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ is our very last aster to flower, but its season is still longer than most. I love its simplicity and soft, moody colour, but it has been out for so long now that sometimes I forget to look. This is one of the joys of the mantlepiece and of hanging on so late to make you refocus. Not so Rosa x odorata ‘Bengal Crimson’, for it is hard to pass by this strength of colour in the gathering monochrome of winter. I have given our plant the most sheltered corner I have, because it is always trying to push growth which gets savaged by cold winds. Here, in the lee of the wall at the end of the house, it flowers intermittently, often through January, paled then by the cold, but always welcome. Close by and also basking in the shelter of the warm wall is Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’, another plant that would continue to flower uninterrupted if we did not have the freeze.

Next year I will protect the spider chrysanthemums, which come so late and need it to survive the frosts. This is one of the few that have survived the recent cold spell. I have not grown ‘Saratov Lilac’ before, but have taken cuttings which are in the frame to try again next year. I have also ordered several more to test my end of season resolve and hope a make-shift shelter of canes and sacking will suffice when the weather cools in October. We got away with it when I grew them in London, but not here where the frost is reliable and helps us to respect the season.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 December 2019

We have just returned from Greece and a browned and dusty landscape that had not seen water since April. We arrived back to a season changed. Fields deep and lush with grass, hedges flashing autumn colour, dimmed as they reached into a shroud of drizzle. Our distinctive line of beech at the end of the valley all but hidden by cloud and windfalls shadowing the slopes beneath the apple trees in the orchard where, just a fortnight before, the branches had been weighted. It took a day to retune the eye, but here I sit not a week later with the sun streaming in over my desk and the studio doors wide open to the garden. It is the stillest, most perfect day of autumn and the garden has weathered well. Aged too by the window of time we have been away, but certainly not lesser now that we are in step again with the season. Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Chasmanthium latifolium

As a way back into the garden this morning we have picked a posy to mark a feeling of this change. The Chasmanthium latifolium are probably at their best, coppery-bronze and hovering above their still lime-green leaves. The perfectly flat flowers appear to have been pressed in a book. Like metallic paillettes they shimmer and bob in the slightest of breezes. I must admit to not having understood the requirements of this plant until recently and, though it is adaptable to a little shade and sun, it likes some shelter to flourish. Where I have used it in China in the searing heat of a Shanghai summer it has done superbly, spilling in a fountain of flower held well above the strappy foliage. It must like the humidity there. In the UK I have found it does best with some protection from the wind. My best plants here are on the leeward side of hawthorns, those in the same planting to the windward side have all but failed. It is a grass that is worth the time and effort to make its acquaintance.

Though the seedheads which mark the life that come before them now outweigh the flower in the garden, we have plenty to ground a posy. Scarcity makes late flower that much more precious and I like to make sure that we have smatterings amongst the late-season grasses. Brick-red schizostylis, flashes of late, navy salvia and clouds of powder blue asters pull your eye through the gauziness. The last push of Indian summer heat has yielded a late crop of dahlia, which have yet to be tickled by cold. I have three species here in the garden specifically for this moment. All singles and delicate in their demeanour. The white form of Dahlia merckii and the brightly mauve D. australis have shown their cold-hardiness and remain in the ground over winter with a mulch, but the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri in this posy is new to me.

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’

I hope it is hardy enough to stay in the ground here. As soon as frost blackens the foliage, each plant will be mulched with a mound of compost to protect the tubers from frost. Distinctive for its feathered, ferny foliage and reaching, wiry limbs, this first year has shown my plants attaining about a metre, two thirds of their promise once they are established. This is not a showy plant, the flowers sparse and delicately suspended, but the colour is a punchy and rich tangerine orange, the boss of stamens egg-yolk yellow. We have it here with Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’, which is also how it is teamed in the garden. ‘Little Henry’ is a shorter form of R. s. ‘Henry Eilers’ and, at about 60 to 90cm, better for being self-supporting. Usually I shy away from short forms, the elegance of the parent often being lost in horticultural selection, but ‘Little Henry’ is a keeper. They have been in flower now since the end of August and will only be dimmed by frost. Where you have to give yourself over to a Black-eyed-Susan and their flare of artificial sunlight, the rolled petals of ‘Little Henry’ are matt and a sophisticated shade of straw yellow, revealing just a flash of gold as the quills splay flat at the ends.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Ipomoea lobata

We have waited a long time this year for the Ipomoea lobata as it sprawled, then mounded and all but eclipsed the sunflowers. We always had a pot of this exotic-looking climber in our Peckham garden, but I have not grown it here yet and have been surprised by the amount of foliage it has produced at the expense of flower. Nasturtiums do this too in rich soil and, if I am to have earlier flower in the future, I will have to seek out an area of poorer ground. That will not suit the sunflowers, but I will find it a suitable partner that it can climb through. It is very easy from seed. Sown in late April in the cold frame and planted out after risk of frost, this is a reliable annual, or at least I thought so until I presented it with my hearty soil. Though late to start flowering this year, it also keeps going till the first frosts, its lick and flame of flower well-suited to the seasonal flare.

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018

Rosa ‘Scharlachglut’

Roses that flower once and then hip beautifully are worth their brevity and we have included R. ‘Scharlachglut’ here, a single rose that I wrote about in flower earlier this year. The hips are much larger than a dog rose, but retain their elegance due to the length of the calyces, which put a Rococo twist on these pumpkin-orange orbs. Despite its ornamental quality when flowering, it is a plant that I am happy to use on the periphery of the garden and one that, in its second incarnation, I can be sure of seeing the season out.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 October 2018 Today’s posy draws upon some of the fine detail in our fully blown August garden. A garden arguably never more voluminous and drawn together now with a growing season behind it. Look up and out and your eye can travel, for the grasses and the sanguisorba are asserting their gauziness. The first of the asters are beginning to colour, in wide-reaching washes that I’ve made deliberately generous. At this time of bulk and volume, however, it is also important to be able to look in and find the detail in something intense, finely drawn and requiring close examination.

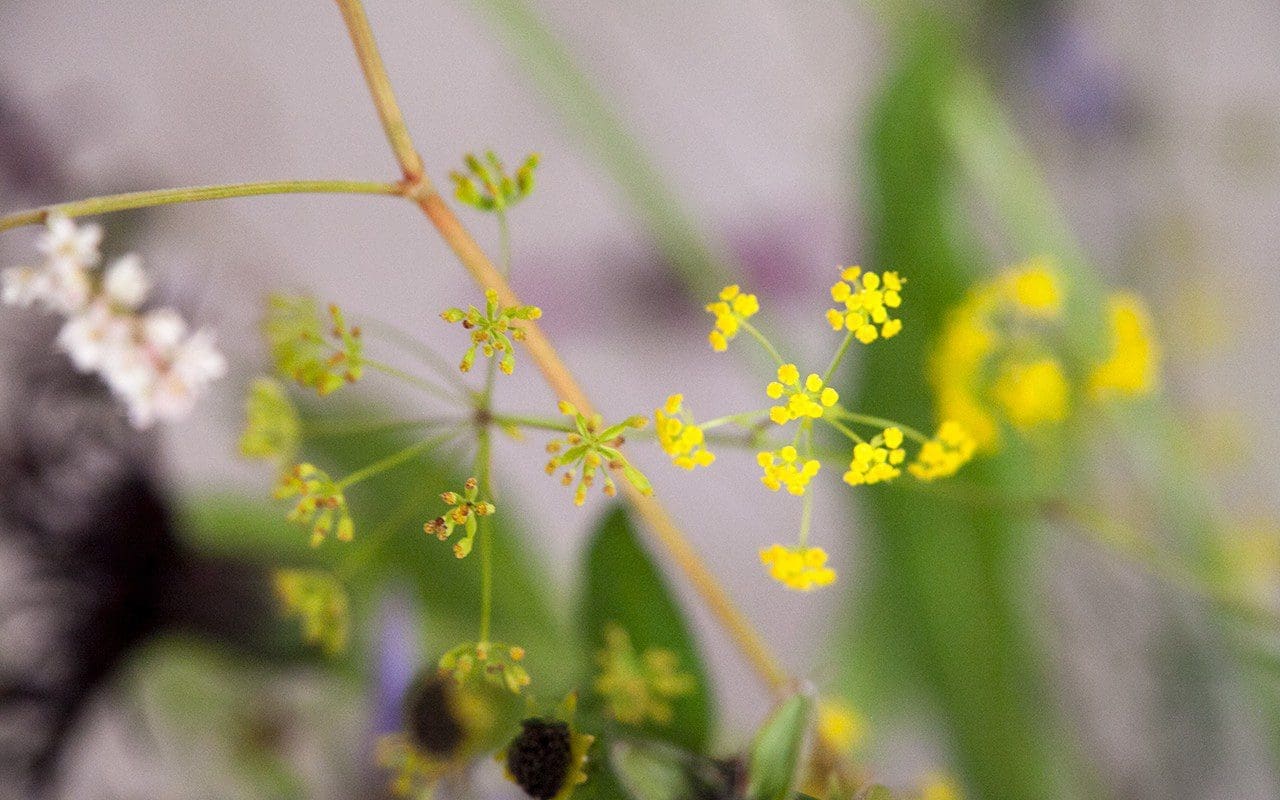

Most of the flowers in the garden here are deliberately small, so that they feel part of the place and cohesive with the scale of the surrounding meadows. Some, like the sanguisorba, appear en masse and register together to create a wash or a veil through which you can suspend an intensity of contrasting colour or screen another mood that appears beyond it. The Bupleurum falcatum, which has now seeded freely in the gravel garden, does just this in the posy to enliven the mood with it’s fine, acidic umbels. At another scale, the Fagopyrum dibotrys does the same in the borders, towering tall and creamy. This perennial buckwheat is prone to wind damage, snapping rather than flexing, but I have found it a sought-after niche close to the buildings to help to narrow the feeling alongside the steps. The scale of its flowers, and their airy distribution, is why it retains a feeling of lightness.

Bupleurum falcatum

Bupleurum falcatum

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Althaea cannabina

Althaea cannabina

Some plants are more interesting for having to find, but their subtlety requires careful placement. The Clematis stans was initially planted down by the barns whilst I was seeing what it was going to do here, but it has been good to have it closer for the detail in the flower is up to regular inspection. This herbaceous clematis is rangy when growing in a little shade but here, out on the blustery slopes, it makes a compact mound of a metre or so across. Prune it hard to a tight framework in February and it rewards you quickly with bright, expectant leaf buds and then foliage that is elegantly cut and not dissimilar to Clematis heracleifolia. In high summer, when the light levels change, it begins to produce clusters of powder-blue flower buds which taper and colour as they move toward flower. Reflexing just the tiniest amount to form a bell like a hyacinth, they have a delicate perfume, which is lost if you bury the plant too deeply in a bed.

Clematis stans

Clematis stans

![]() Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Earlier, in the heat, I was beginning to debate whether I’d take out the Centaurea montana ‘Black Sprite’, for it appeared to hate the brilliance of this summer and the exposure. Already a plant of some modesty, the relief of rain has them with flushed new growth to prove me wrong and it is a delight to come upon it, for it has to be found. The dark, filamentous flowers are as dark as blackcurrants, but combined with silvery Lambs Ears (Stachys byzantina), they are thrown into relief. The hunt is furthered by merging the groups with four-leaved black clover (Trifolium repens ‘Purpurascens Quadrifolium’) and Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. The clover is actually brown, and the potentilla punches colour strongly, but in tiny pinpricks that flash and then disappear as they open and close during the day. Walk the path in the morning and they will be blinking bright, but walk it again in the evening and they are closed, clocked-out for the day.

Pelargonium sidoides

Pelargonium sidoides

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Salvia ‘Nachtvlinder’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’

Over time, and now that the garden has grown and is demanding my attention, I’ve limited the number of pots up around the house. The Pelargonium sidoides are an exception and these are my original plants from what must now be twenty years ago. They have proved their worth despite their subtlety, but I help in having them close by the front door. They are grouped with pots of Tulbaghia ‘Moshoeshoe’. Early in the season and before they start their relay of flower, you might at first think that a potful of tulbaghia were chives, for the majority have a lingering garlicky perfume. The confusion of flower and savoury association is not always digestible, but this selection from Paul Barney at Edulis is an exception. The leaves do not smell and the perfume of the flower is delicate and sweet, particularly at night. They continue to push out flower from June until the frost, when I move the pot to the frame and deny it water for the winter and they survived last winter to prove their resistance when kept on the dry side.

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Geranium ‘Sandrine’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’

Succisella inflexa

Succisella inflexa

There are several new additions to the garden this year on which I am keeping a close watch and reserving my judgement, but Geranium ‘Sandrine’ looks promising. It is a little larger flowered than G. ‘Anne Folkard’, but it has a similar rangy habit and bright green foliage and will find its way amongst other plants, so far without dominating. The flowers, which with many perennial geraniums are bang and bust, do not come all at once, but stagger themselves throughout the summer. This makes them more precious and they pulse with their darkly-veined centres. Succisella inflexa, a Balkan perennial, is entirely new to me, but this looks good for being so late in the season. Finely elongated foliage scales the stems, but stops to leave the thimbles of pale lilac flower hovering at knee height. It has a similar presence to Devil’s-bit Scabious, which is flowering now too in this window between summer and autumn. We will see if it comes back with good behaviour next year, but for now I am watching closely.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 18 August 2018

The last few weeks of growth have been remarkable, the volume and intensity lusher for the wet start and the thunderous, still growing weather. In this lead up to summer the garden was texturally wonderful, the layering of foliage acute for the absence or scarcity of flower. Finely divided mounds of sanguisorba, spearing iris and mounding deschampsia all readying themselves, but yet to show colour. A sense of expectation and the build up to the first round of early summer perennials we have today in this posy.

The colour in the garden is designed to come in waves, like a swathe of buttercups in a meadow, that leads your eye from one place to the next and builds in intensity and then dims as the next thing takes over. After an awakening of single peonies, the salvias are the next contrast to the foundation of greens, which I like here for their ease in the landscape. Though I have never found our native Meadow Clary (Salvia pratensis) on the land, it felt right to bring it into the garden in its cultivated form. We have two named varieties which are early to show and good for their verticality. Salvia pratensis ‘Indigo’, a rich, well-named blue and Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’, which was planted last autumn and is flowering here for the first time this year.

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Salvia pratensis ‘Lapis Lazuli’

Where ‘Indigo’ is perfectly named, ‘Lapis Lazuli’ has nothing of the intensity of the stone it is named after, nor of the ultramarine pigment derived from it. I have a nugget on my windowsill which I found once in Greece, sparkling in crystal clear shallows and catching my eye like a magpie’s. Although I was expecting something brighter and cleaner in colour like my find, the clear, soft pink of ‘Lapis Lazuli’ is anything but disappointing. It has been in flower now since early May for a whole three weeks longer than it’s cousin ‘Indigo’, rising up to two feet in widely spaced spires from a rosette of puckered, matt foliage. I expect it to still be looking good at the end of the month, but shortly before it starts to run out of steam, it will be cut to the base to encourage a second flush.

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’

The first cut back is always hard, because the salvias are a magnet to moths and bees, but we performed the same severity of cut on ‘Indigo’ last year and it rewarded us with a new foliage and then flower in August. Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, the second of the salvias in this posy and far better named for it’s jewel-like colouring, will also respond to the same treatment, but it is important to act before the energy has gone out of the plant by curtailing its show before it finishes flowering naturally. Energy put into seed will thus be saved and replaced with more flower and the reward of fresh new growth.

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’

The cirsium and the cephalaria are also encouraged to produce a second round of foliage by cutting them to the base immediately after they flower. Though they are less inclined to throw out more flower, refreshed foliage is just as useful in an August garden, which needs the greens from this early part of the summer to keep the garden looking lively. The Cirsium rivulare ‘Trevor’s Blue Wonder’ in this bunch grows down by the barns, where its early show coincides with baptisia. Though not remotely blue – a theme that is coming through in this posy, it seems – I love the bluer purple of this form just as much as the garnet red of the Cirsium rivulare ‘Atropurpureum’. These early thistles like plenty of light around their basal clump of foliage and look best for having the air you need to appreciate the way their flowers are held high and free of foliage.

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea

Cephalaria gigantea is similar in its requirements and looks best when it can punch into air without competition. I grow it as an emergent amongst low Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ at the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido, where they grow ten feet tall on either side of a winding path. The creamy yellow flowers are delightfully sparse and the terminus of a rangy cage of airy growth. Here on our hillside they grow six or seven feet at most and right now appear head and shoulders above their partners. A single plant will leave a sizable hole in a planting if you choose to fell it after flowering, as I do for fresh growth, so it is wise to combine it with later performing partners that ease its temporary absence. Asters, grasses and sanguisorba cover for me here.

I have two more species that are part of the new planting and will flower for me for the first time here this year. Cephalaria alpina is a smaller cousin which is more delicate in all its parts, terminating at about four feet and forming a low mound of divided foliage. Cephalaria dipsacoides, teasle-like in its naming and also in its vertical nature, is up to six feet tall, but grows upright from the base. Creamy in colour like its cousins, but differing from all the plants in this posy in being later to flower and prolifically seeding if it likes you. Although I love its seed heads and the structure they offer the autumn garden, I will be cutting the plants down prematurely before they seed. A practice I am having to employ here with several of the self-seeders, as I do not have the manpower to manage the progeny.

Knautia macedonica

Knautia macedonica

A case in point being Knautia macedonica, that I will now treat as a useful filler where I need something fast and reliable. Our ground is almost too rich for this pioneer and in year two the plants splay fatly where they have been living too well. It too seeds prolifically, and my failure to deadhead them last summer resulted in a rash of seedlings this spring, which showed that it could be a problem if left to go native. A few seedlings on standby, however, will provide me with gap fillers where I need them and a succession of this ruby-red scabious that hovers amongst its neighbours. We pull any pink seedlings, favouring the bloodline of those with darker genes.

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea

Stipa gigantea, the Giant Oat Grass is a plant that I have not grown since Home Farm, where it was a mainstay of the Barn Garden. For a while this grass became so fashionable that I avoided using it, despite its obvious beauty and, without enough room to grow it in the Peckham garden, I gave myself a breather. However, I am very happy to have it back and have given it the room it needs to look its best and for its low mound of evergreen foliage to get the light it needs. Right now it is at its most captivating, the lofty panicles, pale copper before turning gold and heavy with yellow pollen, dancing lightly to catch the long evening light. It is an early grass, bolting sky-bound plumes in May and taking June in a shower of luminosity and light.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 16 June 2018

It has been a long, slow start to spring, but at last we have movement. The snakeshead fritillaries are chequering the slopes behind the house and crossing over with early daffodils that this year were a whole two weeks late. The long wait will now see a rush as everything comes together, but reflecting the last few weeks of slim pickings we have kept things simple in this April gathering.

The wet weather has hit hard this year and Tulip Fire has run rampant through the tulip bed. We mass the tulips together in a random mix of six or seven varieties in the kitchen garden and experiment with a new colour palette and untried varieties every year. This year we planned for soft reds, pinks, oranges and apricots with an undercurrent of deep purples. However, we did not plan for the angst that has come with the mistake of replanting too soon in the same place. The Tulip Fire (Botrytis tulipae) probably came in with the bulbs that were grown in the same bed two years ago. A dry spring that year most likely limited its impact and it went unseen. This wouldn’t have been a problem if we’d not replanted in the same place for three to five years.

We will not be making the mistake again, for the majority of this year’s flowers are withered, pock-marked and streaked, the foliage melted on the worst affected. As soon as the flowers that are harvestable have been cut, we will dig up the bulbs and burn them on the bonfire. It has been a hard lesson after a long winter and one never to be forgotten, but we have managed to salvage enough to appreciate close up.

Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’

Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’

We will be trying Tulipa ‘Van Eijk’ again, for its faded pink exterior which conceals the surprise of a bright scarlet interior. The flowers enlarge and age gracefully, first to a strong lipstick pink before ending up a washed rose with the texture and shine of taffeta. It is said to be a variety that comes back for several years without the need for lifting, so next year I will try it by itself in some fresh ground. Planting in late November or early December when the weather is colder is said to diminish the impact of the botrytis should it already be in the ground. Grown on their own and not in the mass of different varieties, they may stand a better chance of staying clean. We have now kept a note to move our cutting tulips between beds on a five year rotation.

Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’

Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’

Tulips are remarkable for their ability to grow and adjust in a vase. The long-stemmed, large-flowered varieties exaggerate the quiet choreography that sees their initial placement becoming something entirely different as the flowers arc and sway. The complexity of colours in Tulipa ‘Apricot Impression’ is promising. The raspberry pink blush in the centre of each petal is quite marked to start with, but suffuses them as the flowers age creating an overall impression of strong coral pink bleeding out to true apricot. The insides are an intense, lacquered orange with large black blotches at the base and provide voluptuous drama as they splay open with abandon. Though our choice of tulips has been somewhat pared back this year, it is good to have enough to get a taste of the selections we’d planned.

Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’

Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’

This is the first time I have grown the Crown Imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) here, and their story has been entirely different. Up early, the reptilian buds spearing the soil in March, and quickly rearing above the dormant world around them, their glossy presence has been so very welcome. I have drifted them in number on the steep slopes at the entrance of the new garden amongst the rangy Paeonia delavayi. Fritillaria imperialis ‘Rubra’ has strong colouring with dark, bronze stems and rust orange flowers that work well with the emerging copper-flushed foliage of the peonies. Although there is an exotic air to the combination, it somehow works here up close to the buildings. It is a combination that you might imagine coming together through the Silk Route, China and the Middle East. However, plant hunters had already introduced the fritillaria from Persia in the mid 1500’s, and so it also has a presence that speaks of a particular kind of old English garden.

At the opening of the Cedric Morris exhibition at The Garden Museum this week Crown Imperials were a key component of Shane Connolly’s floral arrangements, scenting the nave with their appealingly foxy perfume. The smell is said to keep rodents and moles at bay and, though potent, is not unpleasant in my opinion. Morris’ painting Easter Bouquet (1934) captured them exuberantly in an arrangement from his garden at Benton End, which updates the still lives of the Dutch Masters with muscularity and vibrant colour. Rich, evocative and full of vigour, the paintings confirmed to me why we push against the odds to garden.

I planted half the bulbs on their side to see if it is true that they are less likely to rot, and the other half facing up. However, contrary to advice the two failures were bulbs planted on their sides. I also planted deep to encourage re-flowering in future years. The bulbs are as big as large onions, but it is worth planting them at three times their depth since they are prone to coming up blind when planted shallowly. In their homeland in the Middle East, they can be seen in the dry valleys in their thousands after the winter rains, so I am hoping that our hot, dry slopes here suit them. They are teamed with a late molinia and asters, to cover for the gap they will leave when they go into summer dormancy.

Bergenia emeiensis hybrid

Bergenia emeiensis hybrid

The third component in this collection is a pink hybrid form of Bergenia emeinsis. It was given to me by Fergus Garret, who tells me it was handed down by the great nursery woman Elizabeth Strangman with the words that it was a “good plant”. Sure enough, despite its reputation for not being reliably hardy, it has done well for me and flowered prolifically for the first time this year amongst dark leaved Ranunculus ficaria ‘Brazen Hussy’. However, the combination was far from right, the sugary pink of the bergenia clashing unashamedly with the chrome yellow celandines. A combination Christopher Lloyd may well have admired, but not one that feels right here.

However, the elegant flowers are held on tall stems and the leaves are small and neat, so it has been found a new home in the shade at the studio garden in London, where it can be eye-catching when in season against a simple green backdrop. Though this recently introduced species from China grows in moist crevices in Sichuan, it is happy to adapt and is so prolific in flower that I had to find it a place where its early showiness feels right, rather than getting rid of a good plant. More lessons learned, and more to come now that the tide has finally turned.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 April 2018

The first posy of March was picked last week, ahead of the cold north-easterlies and the snow that plunged us back into winter. The galanthus, the primroses and the wild narcissus that just last week were tilted in bud, are buried now in snowdrifts as March comes in, roaring like a lion. In the garden the hunt for new life has also been halted, but we have gained the time to seek out the minutiae of change. Newly visible buds, stark and green against the whiteout on the hawthorn and the Cornus mas in full and oblivious flower.

The Pulmonaria rubra stirred early in January and, beneath the snow they are already flushed with bloom. I was given a clump by our neighbour Jane and, having never grown it before, I can confirm that it is a doer. The silvered and spotted-leaved lungworts are arguably more dramatic, for they provide a textured foil and foliage that is easily as valuable as their spring show of flower. Give them shade and summer moisture and they will reward you, but the slightest sign of drought and they will sadly succumb to mildew. It is important, therefore, to find them a place that keeps cool. Pulmonaria rubra, however, seems altogether more adaptable and when the thaw comes they will flower unhalting until summer.

Pulmonaria rubra

Pulmonaria rubra

Despite its modest presence – it has plain, green foliage and soft, coral flowers – I have enjoyed its willingness and ease on the sunny banks close to the studio where, from the veranda, you can hear the buzz of bumblebees. They love it, as do the first early honeybees and the heavy soil there suits it too. So far it has taken the sun and dry summer weather with no more than a little flagging in midday heat. I have planned for shade with the young Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ that grow alongside and for there to be hellebores there when I have the shade for sure. The lungwort and the Lenten roses will be good in combination and we have experimented here in the bunch with a spotted dusky pink hybrid, whose colouring makes something more of the lungwort. This year it became clear that the red hellebores are just that bit later than the blacks, greens, yellows and picotees, whose earlier buds were ravaged by mice. Sometimes disasters teach you as much as triumphs.

Helleborus x hybridus Single Pink Blotched

Helleborus x hybridus Single Pink Blotched

The last of the winter is held in the Bergenia purpurascens which colours from a deep, coppery green to the colour and shine of oxblood leather in the cold months. This form, which I first saw growing in Beth Chatto’s gravel garden, was initially called ‘Helen Dillon’ after the Irish plantswoman and gardener, but has now been renamed ‘Irish Crimson’. I like it for the scale of the leaf which is finely drawn and held upright to catch the winter sun.

Though bergenia are a stalwart of shade, it is worth finding Bergenia purpurascens a position in sunshine so that the leaves can be backlit in winter. The glowing foliage makes up for the absence of flower elsewhere and is a foil to the first bulbs. I have just one clump which is slowly increasing, but I plan to split it on a year on/year off basis to have enough to mingle it with fine stemmed Narcissus jonquilla and white violets. Though bergenias are tough and reliable, I have found that they are magnets for vine weevil. The tell-tale notches to the edge of the leaf are made by the adult and these signs will show you that there are grubs eating the roots. An autumn application of nematodes should help in controlling the problem if it develops.

Bergenia purpurascens ‘Irish Crimson’

Bergenia purpurascens ‘Irish Crimson’

Salix gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’

Salix gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’

Salix gracilistyla ‘Melanostachys’ is an easy, compact plant which I’ve chosen to grow hard in the gravel surrounding the drive. It has lustrous stems that start out green before turning blood red and throwing out coal-black catkins from early February. They are a surprise and a delight and, some time in the next couple of weeks, each will push out a glowing halo of red anthers. For now, they are planted up at their base with Erigeron karvinskianus to cover until they bulk up. They won’t take long to reach a metre or so in all directions. As they shade out the erigeron, I have also included Viola odorata for its willingness to take their place in the shade. Next year I will add snowdrops to provide a contrast to the darkness of the willow. They will be easy to keep to a waist high bush with the longest growth being pruned out for catkins as an accompaniment to the last of the winter or the first of the spring pickings.

___________________________________

In memory of

Enid Brett Morgan

28 March 1937 – 28 February 2018

I picked this posy last Sunday with mum on my mind. My brother was looking after her, giving me a day’s respite from sharing the care of her at home at the end of her life. I didn’t know then that she would leave us so quickly this week. However, looking at the spareness and sombreness of this arrangement now, shows me that somewhere deep down I did. Mum loved hellebores. Coral and old rose were two of her favourite colours.

Huw Morgan

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 3 March 2018

The last week has seen a subtle shift, with a hint of the next season in the air. With cool nights and mist lolling in the hollows, the garden is between two seasons. The brilliant lythrum spires have finally run out of bud and, like sparklers fizzing their length, are suddenly extinguished. The dry days have been spun with the flock from the white rosebay willow herb caught on the breeze. I have planted it on the edges of the garden to blur the boundaries and, after weeks of flower, it is finally running to seed. I know it will need managing as it is a prodigious runner, but thank goodness it is not like our pink native Chamaenerion angustifolium, for the the seed is sterile.

This week’s bunch is a push against this mood, which can all too easily descend as summer runs out of steam and autumn is yet to take over. Over the years I’ve learned to plan for the between seasons lull and now no longer fear it. The Angelica sylvestris is a perfect example of a plant that steps in to fill the gap. In the ditch where we have cleared the damp ground of bramble they are now seeding freely. Although this wetland native has been wonderful since the spring, with it’s coppery foliage and architectural loftiness, the month of August is really its moment. It has been all but invisible for a while, with the grasses staking their position earlier on, but now the pristine umbels are held amongst their spent, tawny seedheads.

Angelica sylvestris

Angelica sylvestris

Some years, when we walk the ditch early in the season, you can spot a particularly fine form with dark, plum-coloured foliage. The dark stems are always a lovely feature of the Angelica but, coupled with dark leaves, they can not be bettered. Each year I mean to save seed of the best forms, but have never remembered to mark the plants before they are over and browned to skeletons. This autumn I plan to bring a selection called ‘Vicar’s Mead’ into the damper, lower slopes of the new garden. I have grown it without success in London, where it was too dry for it and mildew took its toll, but I trust the ground to be hearty enough here. Though biennial Angelica sylvestris will seed freely and, as long as you leave a number of seedlings, you will always get a succession.

In the garden, I have a particularly lovely form of the perennial Angelica edulis, which is planted through the white Persicaria amplexicaule. The substance and loftiness of the umbels with their horizontal conclusion is a good compliment to the finely drawn verticals, which echo the now spent grasses that surround the angelicas in the ditch. Persicaria is a mainstay of my plantings, which I have depended on for years. Happy with the cool of company at the root and with its head out in the sun, its lush foliage is an excellent team player. Good for the first half of the summer with its overlapping shield-shaped leaves, you know the season is progressing when the first spires arrive at the end of July. Again, August is their month, but they will sail through September and still be firing away in October with the asters. Here, for contrast with the blue, is a new favourite, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’, which is tall enough to be making its way through the Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’, and is an enlivening shade of hot pink.

Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

The Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’ is a late-season grass. Slow to get started in the early summer and needing space early on so as not to be overwhelmed by early-into-leaf companions. An American native known as Switch Grass, it is happiest on lean ground and in bright conditions. Here it is better in soil that is drier or it will lean and topple. I have it on the upper, free-draining slopes where it is already showing colour with reddened tips to the foliage. The plum-coloured flowering panicles are so fine and delicate that you can see through their dusky framework. By the end of the month they will ascend to a final height of about a metre and will then go on to colour brilliantly in October, fiery and lit with their own inner light it seems.

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

I have them planted close, but not too close, to the Cirsium canum, which is as lush as the grass is fine. I bought this perennial thistle from Special Plants where Derry Watkins has it growing in her garden. She swore then that it wasn’t a seeder, as I had been stung by its similar cousin, the native Cirsium tuberosum. The latter has now been banished from the garden to the ditch banks for bad behaviour in the seeding department and, for the past three years, has been kept in check by the competition. When I last saw Derry and asked her if her C. canum had started to seed she said, “a little”, which was due caution, so I will raze my plants when the main show is over to avoid the inevitable. Their stature, reach and poise are beautiful though, the brilliant pink thimbles of flower spotting colour in mid-air just above our heads and humming with bees.

Cirsium canum

Cirsium canum

Succisa pratensis

Succisa pratensis

Though at an altogether smaller scale, the Devil’s Bit Scabious has a similar feeling in the suspension of flower on wiry stems. Another native, Succisa pratensis is a late-performing meadow dweller, happiest where the soil is moist and picking up where many other natives have gone over in August. My original plant, a dark blue selection called ‘Derby Purple’ was the parent of the seedlings in this bunch. They came easily from seed, germinating the same autumn they were sown and flowering just a year later in the new plantings. Although the flowers are darker than the native, they are not as rich as their parent, but they are a wonderful thing to have hovering around in this between season moment. A neat rosette of foliage, that will slowly increase and clump, is easily combined in well-mannered company. I will keep them away from the Cirsium and run them instead through the openly spaced Switch Grass and be happy in the knowledge that their contribution will help to bridge the season.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 August 2017

And so the balance has shifted. The energy of the race to the longest day of the year already dimming. It is a subtle change, but even now it is in evidence with the grasses going to seed in the meadows, May’s vibrant greens flattening and the first of the bindweed replacing the dogroses to light the hedgerows. The last few days of searing heat have pushed this high summer feeling still further and this bunch from the garden reflects something of the new mood.

It is with much excitement that the Romneya coulteri flowered for the first time this year, and no surprise that they chose to do so in weather that must have reminded them of home. See the Californian Tree Poppy in the southern parts of the state where it runs through the rubbly hillsides and you understand why it should be given the hottest, most free-draining position you can offer it. I have it here, facing south, at the base of the barn wall, where the soil is rarely damp for long. It is a choice position – and there are few on our hillside that offer such a baking – but it was not a difficult decision to give the space up to one of my all-time favourites.

I first saw the tree poppy growing in Brighton where it had taken over the tiny front garden of one of my father’s friends and had made the seaward-facing ground its home. Towering at eight feet or so above the pavement and all but obscuring the bay window (there was no need for curtains), from inside the house the crumpled, glistening petals were filled with summer light. The luminosity of the flowers is amplified by a yolk-yellow, globular boss of stamens which dust the petals with pollen as they flutter in the breeze. Hovering on long stalks reaching towards the sun, held amongst finely cut blue-grey foliage, they cannot help but capture all the light that is going. For me the mood they create is the epitome of summer. I have given it the space to claim this moment and have repeated it three times amongst jagged, silver cardoons and ethereal Althaea cannabina.

Romneya coulteri

Romneya coulteri

Romneya hate disturbance, so you have to be sure you know where you want it and not succumb to the temptation of moving it, should it decide it likes you. I’ve found they are fickle and can easily succumb to verticillium wilt in our damp climate when they are young, so I usually build in loss and plant more than I need. Hence the repeat along the barn wall but, in this instance, all three plants have so far thrived, sulking a little in their first year, rising up to a metre or so, but remaining blind and without flower. This year they are looking much more like themselves and have begun to take their position. I’II expect them to attain full stature in a couple of years and we will see then if they start to run, as they can and do in search of new territory. However, they are easily curtailed as long as you slice the runners with a spade and are not tempted to pull the runner back to base and disturb the central root system. Although they will regenerate if the winter hasn’t been hard enough to floor last years growth, it is best to cut the stems hard to the base in March after the worst of the winter has run its course. New shoots are rapid and lush and altogether better looking.

Eryngium giganteum ‘Silver Ghost’

Eryngium giganteum ‘Silver Ghost’

Gaura lindheimerei with Achillea ‘Moonshine’ & Lychnis coronaria

Gaura lindheimerei with Achillea ‘Moonshine’ & Lychnis coronaria

In the gravel, that surrounds the barns, I have been playing with a number of self-seeders to make the buildings feel like the garden has made its home there. Eryngium giganteum ‘Silver Ghost’ is one that I sowed directly from fresh seed given to me by Chris and Toby Marchant of Orchard Dene Nursery. I’d admired the plants at the nursery for their more acutely veined and crested flowers. It is showier than the species, without feeling like it has lost any charm. The common name for Eryngium giganteum, ‘Miss Willmott’s Ghost’, is attributed to Ellen Willmott, the English horticulturist, who was said to have carried seeds in her pockets at all times and distributed them in a trail throughout gardens she visited. If it finds a home that is to its liking, with plenty of sun and no competition to the basal rosette, this biennial is great for never being in the same place and for the chance happenings that come about when you let it find it’s own position. It is good here with the flutter of Gaura lindheimeri that creates a shimmering highlight of white, like the sparkle of light on water.

Lychnis coronaria & Achillea ‘Moonshine’

Lychnis coronaria & Achillea ‘Moonshine’

Achillea ‘Moonshine’ is a plant that I have not grown since I was a teenager, where I had it in my yellow border. It was short-lived there in the window of light that fell between the trees in our wooded garden, but I hope to keep it longer here on our sunny hillside despite its requirement for regular division. It is dancing now amongst the contrasting magenta of Lychnis coronaria in a strong wind that has kicked up after the past week’s heat, but is all but oblivious to the buffeting. Perfectly flat heads that huddle at about knee height are the ideal receptacle to harvest the high light and long days. The colour is the brightest, most vibrant sulphur yellow and, now that I see them together in a vase, its brightness further enriches the golden boss of the Romneya to saffron. A new combination for the future, perhaps (for they would surely like the same conditions) and one that would set the tone for the height of summer that is still ahead of us.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 June 2017