ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

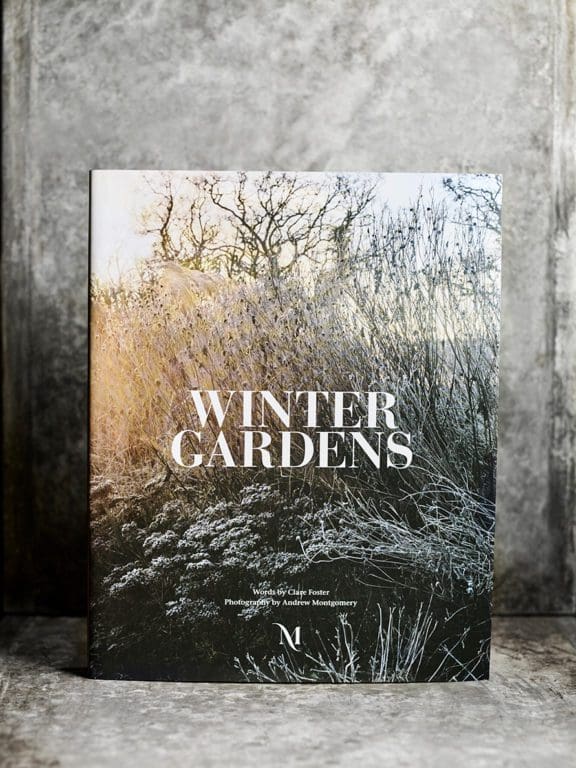

Last December, just days after Christmas, we received an email from Clare Foster, gardens editor at House & Garden magazine. She wanted to know if we would be happy for the garden at Hillside to be photographed by Andrew Montgomery for a new self-published book they were working on together. The focus of the book was to be gardens in winter and they had set themselves the task of getting it written, photographed, designed and published within 10 months.

On a perfect misty morning in early January with the garden covered in hoar frost Andrew arrived just before sunrise. He immediately got to work with total focus and proceeded to work into the early afternoon when the mist finally dissipated and his frost-bitten fingers could take the cold no more. The book has now been published and features gardens by Arabella Lennox-Boyd, Arne Maynard, Jinny Blom, Piet Oudolf and Tom Stuart-Smith amongst many others. Here Clare and Andrew tell us about how the book came about and what they feel is particular and special about the garden in winter.

Tell me how the idea for the book came about? What inspired you to create a book about winter gardens?

Clare: Andrew and I had worked on a couple of winter garden features for House & Garden and one in particular we had been trying to capture for a couple of years, waiting for the right moment. In lockdown, Andrew started photographing seed heads and ruminating on the idea of doing a book. I seized on the idea and came up with a list of other gardens which I thought captured the beauty of winter in very different ways. We were lucky – the weather was reasonably cold last winter – and we managed to get most of them photographed in atmospheric frost, mist or snow.

Andrew: Winter Gardens came about in December 2020, during the second lock-down. Having seen all my photography commissions put on hold until well into 2021, I had this free time all of a sudden where I could do what I wanted, so decided to photograph and put together my own book. Having spent the previous 10 months, including the first lockdown, putting together a book for Petersham Nurseries which was a self-published project, I knew I could do it. Winter Gardens was the perfect subject. Covid secure, I could shoot whenever I wanted with no human contact. More importantly it appealed to my own personal desire to see gardens in a new way. Stripped of colour, a monochromatic palette where light and shadow became paramount. The gardens became a muse for my love of black and white photography. Mist, snow, frost all enhanced the medium, which I felt had never really been properly explored in garden photography.

Gardens are often referred to as out of season in the winter. Can you tell us why you felt differently?

Clare: When you slow yourself down and really start looking at the garden and landscape in winter you notice the most amazing nuances. It is the sort of beauty that might not jump out at you, but once you adjust your eye it becomes a marvellous thing. There is no such thing as ‘out of season’ – winter is very much a season to be celebrated in the garden, with a chance to slow down and appreciate everything in suspended animation. And the other thing is, if you don’t have the quietness and downtime of winter you don’t appreciate the cycle of growth as it appears again in spring. It’s sort of magical, really.

Andrew: Out of season seems to suggest they have nothing to offer. I had a conversation with one of the gardeners at Great Dixter discussing frost. She remarked that the first frost was always the most magical, as if it signified the curtain call of Autumn, those brown warm shapes and tones suddenly enveloped by a crystal blue cloak, a portent of what is to follow. This sparked the need to witness and photograph this inaugural wintry pistol crack. So over previous winters I have always felt the need to try and capture this moment.

The winter season offers something different to capture, something much more subtle. The garden is dormant, quiet, its bones and earth bereft of colour, where weather dominates the mood and feel of the space, enhancing what is left for us to see. It also gives us a chance to really reflect on what went before, but also gives us hope as to what is to come. Winter is the season of reflection.

How did you go about selecting the gardens you chose for the book? What was the story you were wanting to tell?

Clare: We wanted there to be some very contrasting gardens in the book to show that there are different ways to bring beauty and interest into the winter garden. The book is divided into three sections that take you conceptually through early, mid and late winter, to show that winter is not a static season at all, but has its own momentum towards spring. Three essays group the gardens into different types: Beauty in Decay features gardens with grasses and seedheads; Silhouette and Structure looks at gardens with a stronger topiary framework; and A Shy Flowering contains gardens with winter or earliest spring flowers. The last garden in the book shows everything cut neatly down and mulched ready for spring. One senses the hope of the new year.

Is there anything you learned about the process of gardening while researching, writing and producing the book that was either new to you or came as a surprise?

Clare: I learned to really, really look at the process of senescence in my own garden. In certain plants, the seed heads and stems collapse quickly; others are incredibly strong and last for months and months before you have to fell them in March. I noticed what rain or frost did to my honesty seed heads and this close observation brought so much pleasure. I also learned quite a lot about snowdrops from the head gardener at Lord Heseltine’s garden at Thenford. They have a collection of about 900 varieties and she knows almost everything there is to know about propagating them.

Can you tell us about some of the challenges you face photographing gardens in winter?

Andrew: The challenges – well the obvious one is the cold. It’s debilitating both to people and battery life! Fingers become useless after prolonged exposure to the cold, disconnected from the brain you begin to fumble the camera controls, struggling to operate something which usually you do without looking. The cold becomes tiring, tripods and ladders too cold to touch with bare hands. Gloves, thermals and merino wool layers help massively. Cameras also don’t like the cold, and you have to acclimatise them slowly to the conditions, otherwise condensation builds up on lenses and viewfinders.

There’s also always a chance in the winter that you’re not going to be able to get to the garden you’re supposed to be photographing due to ice or heavy snowfall. Either that or, having headed off at dawn into the frost and snow, you find that by the time you get there it’s disappeared! One of the gardens was a particular challenge and it took four attempts to get the pictures that appear in the book. The garden is just off the M4 not far from London, not an area known for snow. The fourth attempt was only successful as I was supposed to be going down to Dorset to do a shoot that morning, but couldn’t get there as the A303 was snowbound. So I took a gamble on the fact that it was probably snowing at this other garden, which was much closer. This was at 5 a.m. so I just decided to turn up and hope the owners didn’t mind! Of course, I was incredibly lucky and got some beautiful shots of the garden in the snow.

The book is beautifully thought through, laid out and paced. Who designed it for you?

Andrew: I designed and laid out the whole book and the individual gardens and chapters. Editing is a process which I love. Pacing the run of photographs for each garden, juxtaposing images, mixing colour and black and white. It’s just like planning and planting a garden – extremely creative. You are mindful of what comes before and next, not wanting to repeat yourself visually. Always trying to make each image earn its right to be on that page and in the book.

Once I had everything laid out and the gardens organised into chapters, I would then work with a great guy called Anthony Hodgson who was able to put everything into Indesign for me and put the book together for printing. He also handled all the typesetting and font choices in the book.

Andrew, at the book launch you said that the image you took at Hillside which you titled The View to the Tump, ‘is probably the most spiritual picture I have ever taken.’ I’d really like you to expand on that and tell me why.

Andrew: The View to the Tump is an image that had been one of my favourites throughout the book’s editing process. It was the best shot from my day’s shoot at Hillside, but it was when I saw it enlarged to over 3ft by 2ft on the table in the printers that its power really struck me. I became quite emotional seeing it for that first time at that scale. I had only ever viewed it on my computer screen at home where it was no bigger than A4 size. The scale of the print, which was to be hung with two other prints of Hillside for an exhibition to celebrate the book launch of Winter Gardens, had made it an immersive experience.

Once hung on the wall I began to see that the image was a glimpse of another world, familiar to ours yet somehow removed. The gate in the image took on the metaphor of the entry into that other world, as if this was a glimpse of heaven beyond.

Now for me to say these things about any image, let alone one of my own, is unheard of, but this one is different and stems from my emotional reaction to it. This is a rare, profound feeling that has happened only once or twice in all my thirty years of taking photographs, but it’s the spiritual connection that The View to the Tump has that makes it unlike anything I have taken before.

Can you tell me what it is you see in winter seedheads and skeletons, which your son, Clare, described as a ‘a load of depressing old sticks’?

Clare: Every seed head has a different structure, a unique design that is revealed slowly as the plant decays. Some of them are really sturdy and strong, others are delicate and ethereal, but they are all marvels of nature. I find that photographing them sometimes makes me focus more keenly on them, especially if I’m doing close up or macro shots that reveal the tiniest detail. I think this is something that you almost have to learn to do, and I will try and teach my 17 year old son to open his eyes to it. But I don’t think he’s ready yet….

You first contacted us about this book just after Christmas last year, since when you have written, photographed, edited, designed, proofed and published this completely on your own. Can you describe what it has it been like self-publishing a book from scratch in just under a year and what have been the particular challenges?

Clare: It has been a complete whirlwind. We are both incredibly hard workers. We get things done, but it has been a fantastic experience because we have had complete creative control. Obviously Andrew takes the photographs and it was his eye that brought the book together, but he was very open to my suggestions and ideas and together I think we have made something that represents both our creative souls. We have made something with integrity that I think we are both incredibly proud of.

Andrew: The timescale to produce a book of this scale would normally be 1-2 years, so to do it in 10 months would, to a normal publisher, be impossible. We had planned out our production schedule, image editing, design, writing, copy editing and proofing to meet our deadline of July 29th. Files would then be sent to the printers and our book scheduled to arrive mid-October for our November 4th publication deadline.

The challenge was doing this alongside our normal careers at the same time, which put a huge amount of pressure on both of us. We just knuckled down and worked all hours on it. We really wanted the book to be published this winter, not a year later, and it could not come out at any other time of year either.

The most stressful part was waiting for the ship carrying our books to arrive in Portsmouth. The pandemic had played havoc with shipping routes and schedules and watching the boat make its eight week voyage over a live-view feed on the internet with publication day looming was nerve-wracking. In the end I took delivery with just two days to spare!

Now that you have one book under your belts do you have any plans for another? If so, are you able to tell us anything about it?

Clare: Yes – another book is definitely in the pipeline. Another garden book. Watch this space!

Andrew: Well, it’s very exciting that we know what book two will be! It’s going to be another garden based book, but we can’t say more than that. We are aiming to release it sometime in 2023, but to enable us to do that book we are working as hard as we can now to make Winter Gardens the success we feel hopefully it deserves to be!

Winter Gardens costs £45 and is available to buy directly from Montgomery Press.

An exhibition of Andrew’s photographs from the book is being held in the old tithe barn at Thyme, Southrop, near Lechlade until April 4 2022.

Interview: Huw Morgan | All photographs © Andrew Montgomery

Published 4 December 2021

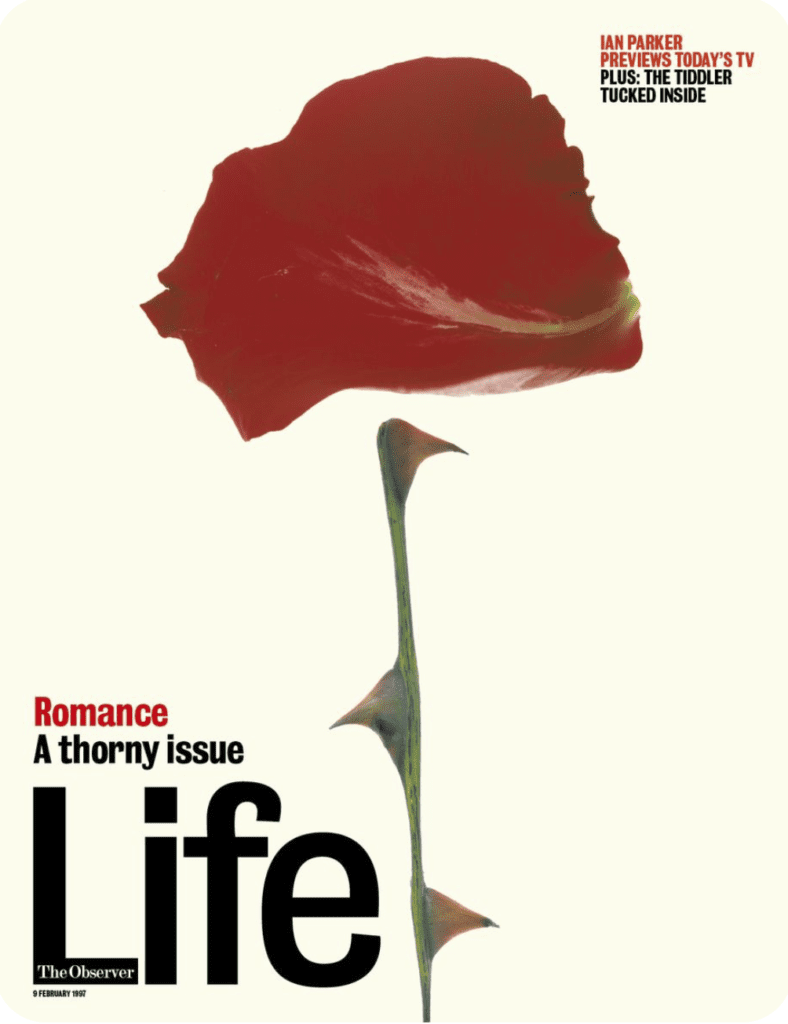

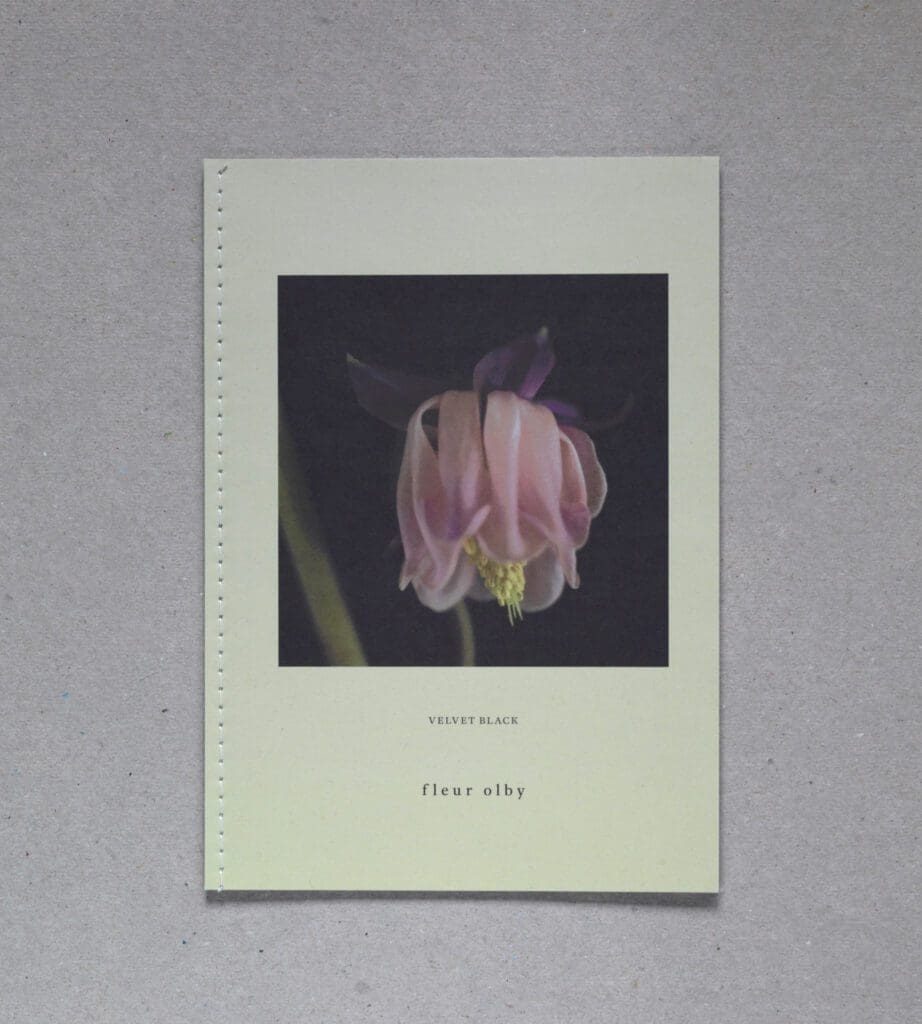

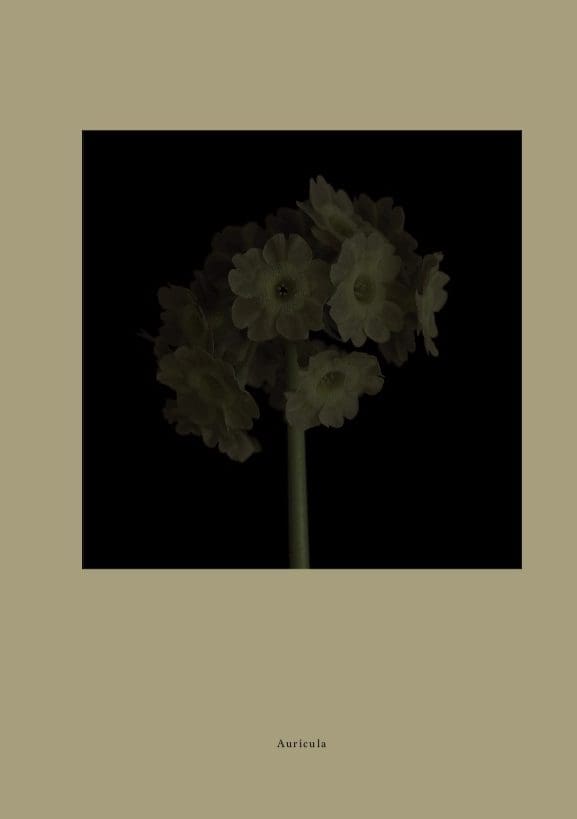

Fleur Olby first came to our attention in the 1990’s with her striking abstract plant portraits which illustrated Monty Don’s gardening column in The Observer Life Magazine. Her interest in shooting in low light prompted us to invite her to photograph the winter garden. So, early this year, and just weeks before lockdown, Fleur came to spend a day and a night at Hillside. As the clocks go back we revisit her vision of the penumbral garden.

Tell me about your interest in nature. When did it begin and were there any key experiences that shaped your relationship to the natural world and plants in particular?

During childhood I became ill with double pneumonia and had to be in an oxygen tent. My Mum brought an oak leaf into the hospital as a gift to look at something beautiful and magical from a tree close to where we lived and the thought of visiting it when I was better. I remember visiting the tree later, although now it all feels dreamlike. There was something then that I still question in the shift in perception of looking at something small in isolation to seeing it in its context of growing on a tree. The enlarged gaze of a child was full of wonder, magic and intrigue, something I have tried to recreate in my still life photography.

How did you realise you wanted to become a photographer?

During my MA in Graphic Design at Central St Martins (1992), I spent a lot of time colour printing in the darkroom, my degree show became purely photographic – Images of environmental and flower still life. My thesis explored the different ways of looking at Nature from abstraction, the single image, still life, the object in its environment, the concept of the Wilderness and a Garden and their uses within the industries of Art, Design and Photography.

I wanted to be able to work within the landscape I grew up in and the magazine aesthetics of still life. At this time, I was entranced by looking at detail, but importantly when I first started making pictures in wilderness places there is an unexplainable feeling found through the camera.

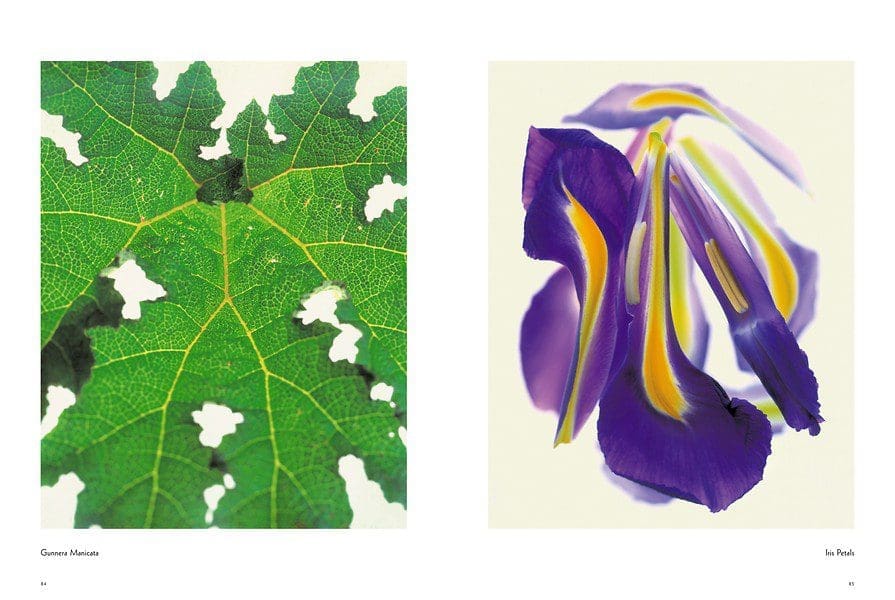

Your work for The Observer Magazine was groundbreaking at the time. Can you explain how your view of plants differed from the norm then?

I was inspired by Monty Don’s writing and both degrees were fine art graphic design – lighting and composition were always experimental. Nick Hall was my first commissioning editor at the Observer and then Jennie Ricketts. He commissioned the garden articles to be an abstraction in still life. The concept of the garden as a still life representation was different then. It was a unique time when my imagery was young and given total creative freedom. For the articles, I would regularly be at the flower market at 4 am and in the lab processing the work at midnight ready for the morning.

Although you were working commercially what made your photography stand out then was that it was clearly the vision of an artist. Can you describe you and your photography’s relationship with the worlds of art and commerce and do you still produce commercial work?

I had a good mix of editorial design and advertising and the two books were the fine art application of my work. After the 2008 financial crash and the evolution of digital capture still-life Photography commissions changed and lifestyle photography replaced a lot of the still life work. After 15 years of commissioned work, I had to change my practice as it became unviable to run a still life studio. I consolidated my archives and started to make personal work. The series are ongoing, but I would also like to work on plant collections again and garden stories.

How did your work develop after your time at The Observer ? I have read that some of the images were used in installations. Now you produce limited edition imprints alongside prints.

The Observer gardening editorial was amongst editorials I contributed to regularly for food and health and beauty. When I stopped shooting for the gardening articles in 2002 the food still life increased and I also worked for some fashion companies for still life and jewellery, perfume and interior still life.

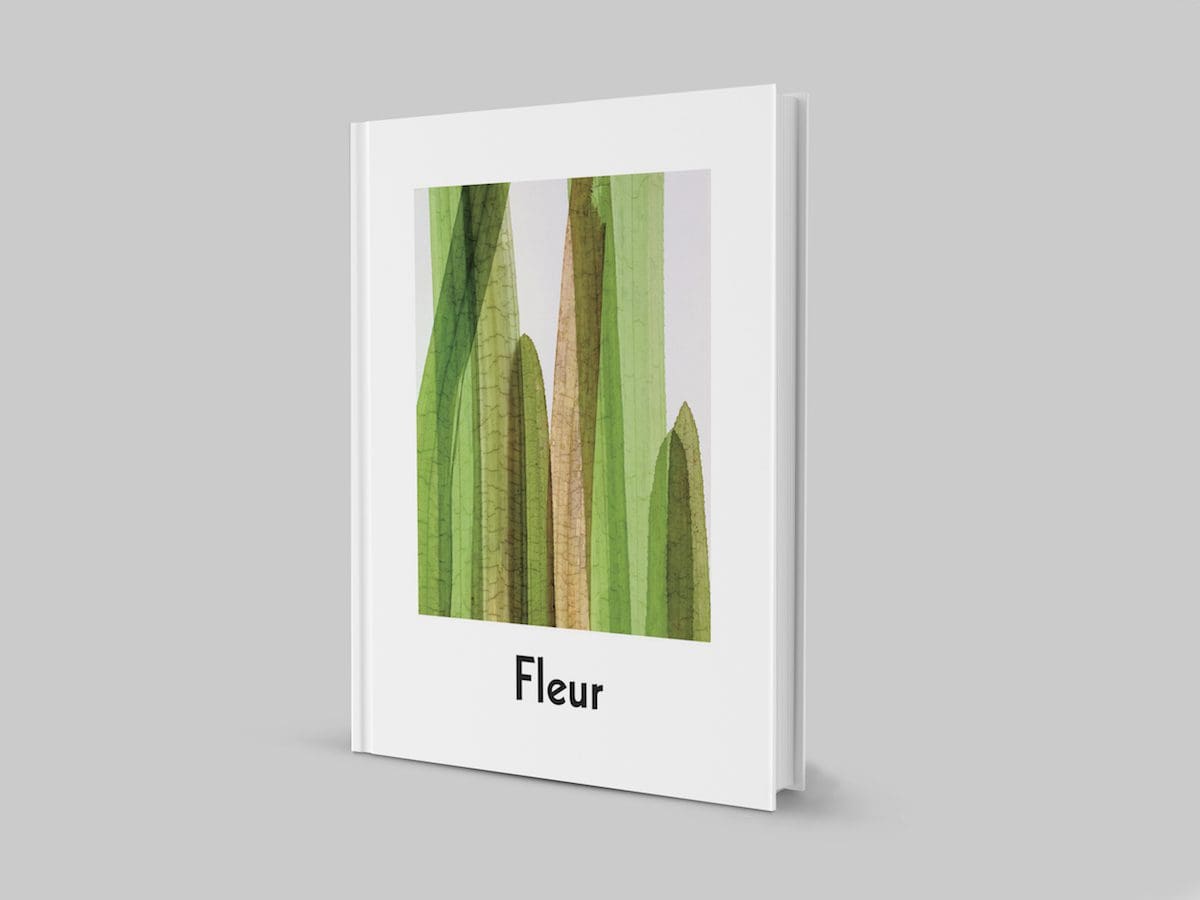

My monograph Fleur: Plant Portraits by Fleur Olby with a foreword by Wayne Ford, was published by FUEL Publishing in 2005, a combination of commissioned and personal work from ten years of floral still life. It was in the Tate Modern and The Photographers’ Gallery bookshops and distributed internationally with DAP and Thames and Hudson.

But after 2008 with two client insolvencies causing further problems after the financial crash, it took me a long time to find a way forward with my archives. The two commissions, Horsetail Equisetum for Gollifer Langston Architects and a textile collaboration with Woven Image in Australia were the archival commissions from that time that enabled me to move forward.

I had started a long-term project about the connection with Nature, Colour from Black. My Imprint has the first publication from these series, Velvet Black and limited edition prints that have exhibited at the Photography Gallery in the Museum of Gdansk and my solo show earlier this year at The Garden Museum, London. The A5 publication launched at Impressions Gallery Photobook Fair in Bradford and the A5 and A6 special edition are currently also at The Photographers’ Gallery bookshop in London. I aim to continue with self-publishing the series in small books and work in collaboration on the projects that evolve from them. Images from other series have also been shown in group shows in the UK and abroad.

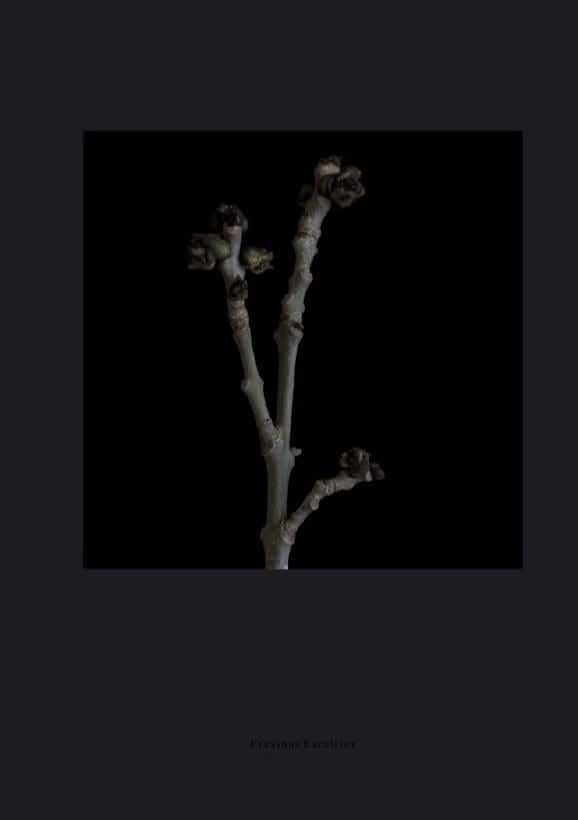

Can you describe your process, and how your choice of film stocks, different formats and use of low light levels create the particular viewpoint you are interested in capturing?

The series artistic aim is to connect dreams and reality and through this work I have experimented with different mediums. It is less about the impact of a single image, my interest is in the pace and change of the narrative. The personal aim is to conserve plants and the elemental feeling of beauty in Nature. My commercial work was studio light, mostly shot on 5/4 Velvia and Provia film.

In my long-term series, the colour is subtle but fully saturated, in natural light. The low light started with the series Velvet Black as a present-day ode back to Victorian plant theatricals, collections and plants from a garden – the correlation between the transience of daylight and blooms.

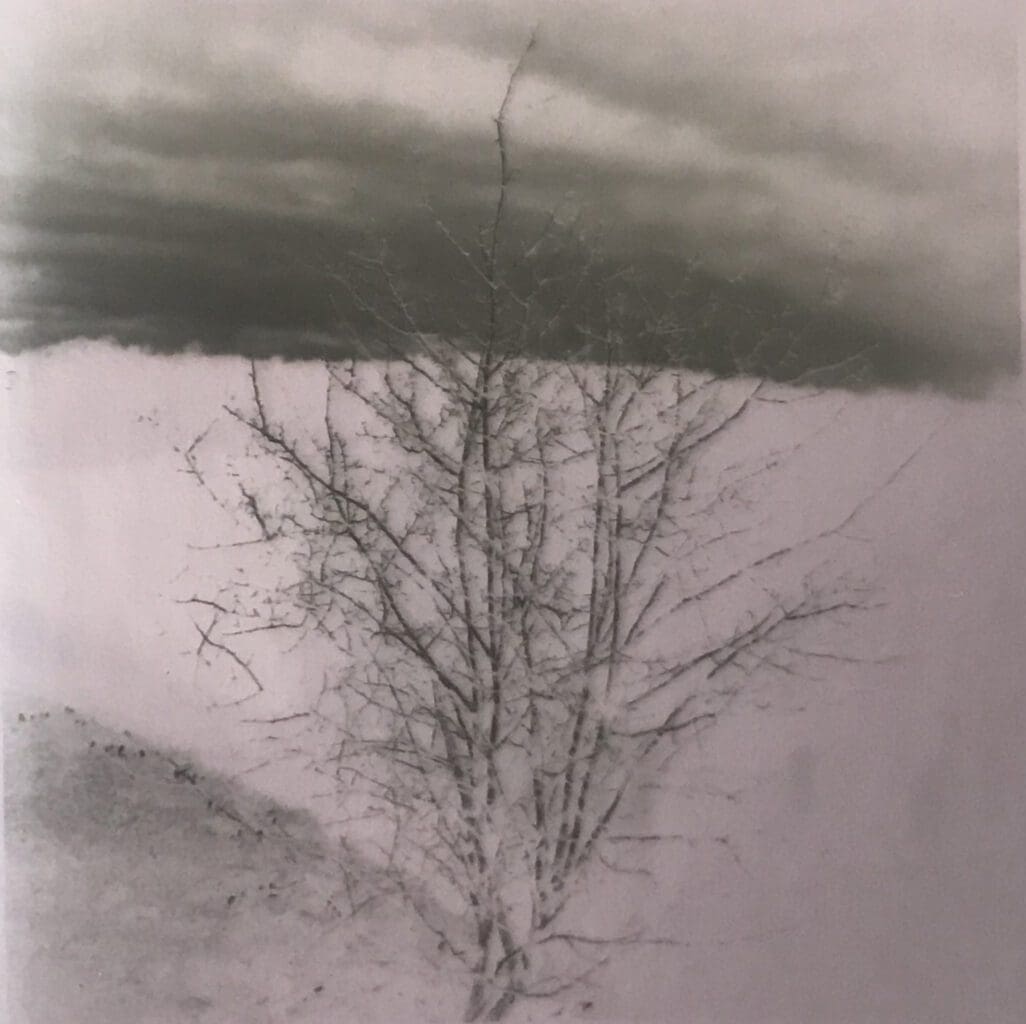

I was also experimenting with my iPhone as I was trying to capture the spontaneity of feeling from walking. My working process has evolved: It begins with walking and pictures that I revisit on medium format for a different kind of precision that allows long exposure. I am now mixing instant images and film from Black and white and colour. The series made at Hillside was the first time I combined the different mediums and shot Dusk, Dawn, Dusk in succession. I used Instax and my phone to find viewpoints from the paths. I remade some of the images on the Ipad to map out the plan.

Then I shot with a Polaroid camera in reasonable light and shot film and digital on medium format at Dusk and Dawn. The film was mostly Ilford, HP5, FP4 and XP2.

There is a quiet intensity to all of your work, a feeling of being tuned in to a different way of seeing the familiar. The fact that you work in series also gives a very strong narrative quality to your images. What would you like us to see in them?

Thank you, that means a lot to me! The quiet intensity was what I needed to reconnect with when I began to revisit childhood places that inspire me on the moors, on the hills, in the garden.

With the narratives about Nature, I wanted to slow down the viewing process and to question the feeling of Beauty through light and repetition within the series. In the book Velvet Black I use the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper and the folded pages to slow down the process in a similar way to a flower press. And the printed absorptance of the page makes the transient process of nature into a permanent object.

There is a distinct balance in your work between wild, elemental landscape and the intimacy and perfection of a single cut flower. What is the relationship between these two worlds for you?

I think this is the path I am trying to narrate between the perfect oak leaf from my childhood to the tree out on the hills.

When we asked you to come and take photographs at Hillside what were your first thoughts ? When you were here were there any particular observations you made about photographing a garden set in landscape?

It was great to hear from you both. I was excited about the thought of visiting Hillside. I remember our conversations about the work you were inviting artists to make and what aspects of the garden they were focusing on. But on arriving I couldn’t think how to divide it up into one particular interest and I knew I wanted to convey feeling.

I arrived between the storms of February, the quiet calm lull in the garden was breathtakingly beautiful. No-one was there until later today.

I started to walk – the paths led me everywhere. Enclosed and defined by the garden in and out of the landscape. I did not know this terrain, the feeling and scale are different, the quiet remains the same – the shape of the hill on the left is gentle and round, it stretches out into another at the front with incredible mature trees. The main garden is perched high up within the undulation of the hills. How will I capture this?

I felt I was intruding the serenity of the place, I stood amongst the plants’ skeletons taller than me and thanked them for remaining standing despite the storm – looked out at the echo of the trees beyond, walked down the hill towards them and looked back up to where I’d been standing – It is like a painting, brushstrokes of layered texture highlighted by the time of the year and the trees and hedges beyond it, darker shapes in repetition above. Light in colour as its ready to be cut for new planting and the two gates take me in and out of place and garden and into wonderment. I’m not sure I can express this.

Then there’s the bridge at the bottom of the stream with wrapped up plants on the edge that I could spend all day shooting, the vegetable garden! The artichokes! The Cavolo Nero – The two architectural stone troughs define the scale of the outdoor space and feel spiritual, a verbascum ode nearby reminds me of my Dad and makes me smile, the hedges, the orchards and the young woodland at the back. Flowers resiliently here and there touched me – intricate planting inspired me. I had to process a plan and start.

I wanted to try and capture this movement, the feelings from walking this dreamworld and its reality. I worked on different cameras in repetition in positive and negative to intensify the shapes and colour and black and white to intensify the feeling and pictorially play with resonance.

Do you feel that you learnt anything new from the time you spent photographing here?

It was immensely helpful to be invited to work like this, and I enjoyed the intensity of making the work. I made a new working process shooting 3 formats and running between captures to put the instant film to process inside and continue with the film outside. I made quite a lot of work in the time and it was the first time I shot constantly connecting dusk and dawn.

It enabled me to see how my work has progressed more clearly and how I can put it together because it was the perfect balance of how the garden and landscape coexist.

How was lockdown for you creatively?

Lockdown happened during my show at The Garden Museum.

I contributed to Quarantine Herbarium’s cyanotype project and the Trace Charity Print Sale which raised money for the charities Crisis and Refuge.

I listened more to the birds, watched the animals’ paths and felt exceptionally close to them and that continues. I was also busy shielding family, and I spent more time growing vegetables which I do as much as possible.

I stopped shooting and started to edit more.

What are you working on now and can you share any ideas you have for future projects?

I have had to revise my plans for this year, events I had committed to were cancelled. I am reworking everything and plan to bring the next series out in 2021.

The full edit of the photographs Fleur took can be seen on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Portrait: Howard Sooley

All other photographs: Fleur Olby

Published 24 October 2020

The two best times to look at the garden are to either end of the day. I would be up at four if I had the reserves, but we are up early when the light is soft and before the sun reaches over the hedge. The stillness of first thing is particular for the feeling of awakening, but there is a charge in the air with the day waiting to happen. When the sun breaks the spell, everything changes as the light flattens and the tasks of the day take over. We wait then until the sun dips low in the sky and the light is softened before resuming our observation.

The long evenings are remarkable in this country and particular this year for the brilliance and stillness of this summer. Evenings were always the time that I used to go down the garden at Hill Cottage to the pair of borders that my father and I made there when I was a teenager. His planting to the left in a border of whites and blues and mine to the right with yellows and clashing magentas. We would spend an hour or so talking things through, observing how things could be bettered or moments where briefly things sang. We would talk about the way the colours changed as the light dropped, the blues beginning to pulse and hover as the low light favoured them, and of the way that the brighter, hotter colours, which had flared during the day, dropped away first.

Huw and I do the same here, using the time when you can see best to workshop the planting and to enjoy the elements that have come together or shifted during the day. The slow evenings are in our favour, for they have an altogether different charge from the awakening of dawn. We let the colour go through its metamorphosis, as the reds, pinks and oranges heat up at sundown and then quickly dim to almost nothing. The violet end of the spectrum then takes over as the gloaming hour assumes its residency, the flowers with the most blue in them appearing to lift from their material origins in these fugitive last minutes. Then, in a shift that you feel but do not necessarily see, the colour is gone and you are left with something else. A garden of textures and form, readying for night. More often than not it is ten before we have even begun to think about supper. It is hard drag yourself inside when your senses are retuned and receptive.

This summer, as much out of desire as necessity, Huw has been photographing the night time garden to extend our experience. I will let him take it from here to explain why.

Dan Pearson

Over the years I have always experimented with my photography. Capturing movement by shooting digital film on a very slow shutter speed and then extracting single frames, selected for the painterly composition of their colour blur. On my old Polaroid camera I would cover the focus sensor, so that images of plantings resembled Impressionist paintings or colour fields. And I have used torches, lanterns and flash to see the garden in a different way by night. With each approach I have been happy, even seeking, to surrender some of my control over the final image to the equipment and technology itself.

However, over the past few years, and so that we can record the garden here properly, I have been actively working to improve my skill with a digital SLR camera and a number of lenses, so it has been a while since I have experimented in this way. At the beginning of June, with the start of the long warm nights, I found myself in the garden at the gloaming hour, having driven down to Somerset after a working day in London. With the warmth, growth had started in earnest and, as the light faded, there were parts of the new garden that it fast became too dark to see clearly. I got out my phone and switched the light on. Suddenly individual plants were thrown into sharp relief against the inky background of hedge, wood and sky. The composition of volumes and heights and the differences in textures became more apparent. Colour was heightened and where, by daylight, the plantings were soft and transparent, now they were graphic and architectural. I immediately started taking photographs on the phone with the flash.

It is a tricky process framing and composing an image when you are, quite literally, shooting in the dark. A series of test shots are necessary to establish the composition and to attain the right distance from the subject so that the flash doesn’t create too much of a hot spot. Even once this has been successfully done, the camera doesn’t always focus accurately in the dark, so each successful shot is arrived at after taking many that do not work. It is then a long process evaluating, editing and then adjusting contrast and colour balance to achieve a satisfactory result.

As the nights grew longer and we wandered the paths later and later each evening, I have been staying out after nightfall to try and capture aspects of the ever-changing picture. As in Tom’s Midnight Garden, the clarity of darkness reveals things invisible by day. The abstraction of the plantings against the velvet black and the fluttering of a thousand moths making of the garden a new mysterious and magical territory.

Huw Morgan

Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 July 2018

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage