ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

The houses in the valley sit on the spring line and in turn the ditches that run alongside every downward moving hedgerow each channel the spring water to the stream that runs below us. We are lucky to have water here, but it is always on the move, descending, passing through and never still. The silvery lines that trace the creases in the winter are all but eclipsed by foliage in the growing season, but we are aware of it always, sounding when the stream is in spate from way below us and babbling in the ditch that lies in the fold of land beyond the garden.

Making a still body of water has always been something we have planned for and over our time here we have found the place for it in the hollow, where the water might collect and you could imagine a stillness beyond the garden. A place where the flow is interrupted and paused before it continues its journey. Somewhere for the sky to come to earth and for reflections to be held and the world quietly magnified.

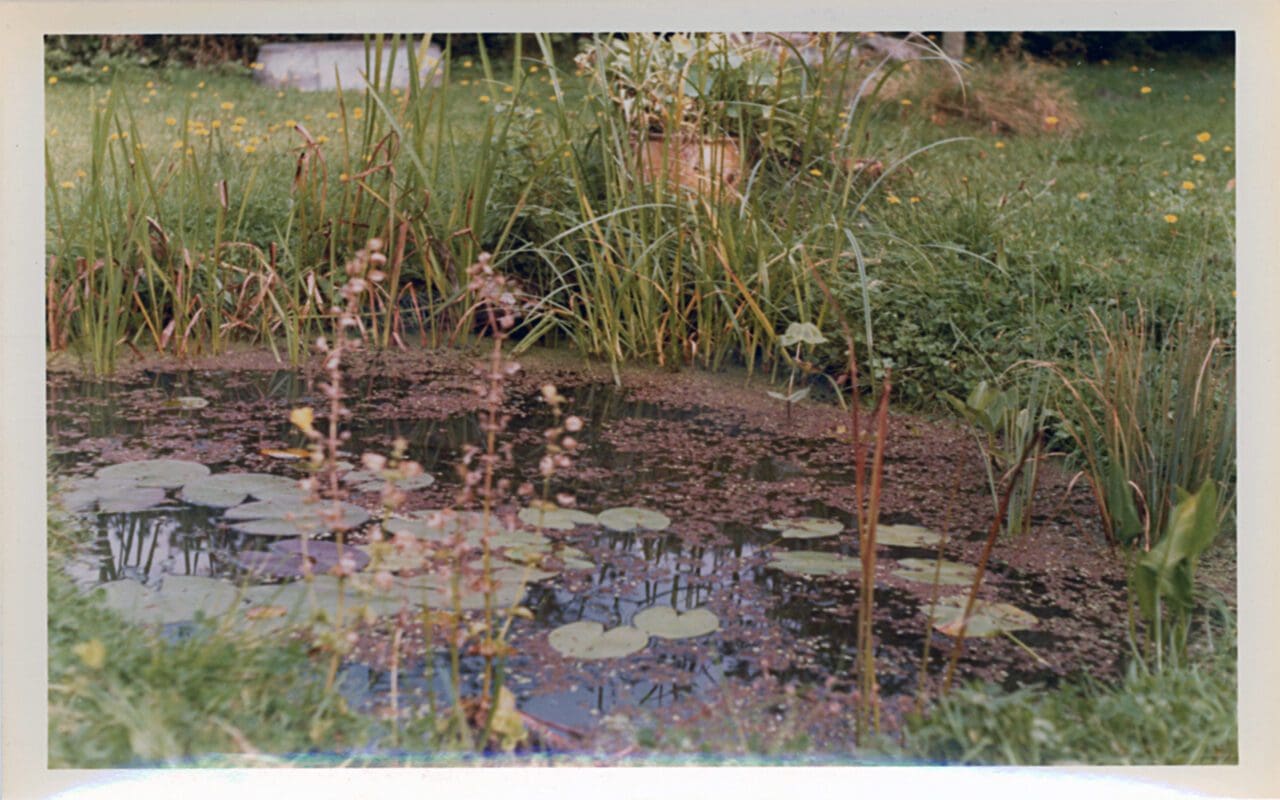

My father made a pond when I was about five and it was lying on the turf banks with my face hovering over the watery lens that I first encountered alchemy. The coming to life from a handful of raw materials and the energy of transformation. It was about five feet by four with a marginal shelf on three sides and the turf of the surrounding orchard folded over the edges to hide the blue plastic liner. I remember the smell of the pond plants pressed into the mud and the clear water soon eclipsing them entirely as it became opaque and green and began its evolution. After a couple of weeks of peering into the gloom, the pond skaters and water boatmen arrived apparently from nowhere and the water suddenly cleared. The muddy-mintiness of the Mentha aquatica was soon travelling into the banks and, like a hand unfolding, the water lilies slipped over the surface with their perfect flatness. Looking underneath and the gelatinous eggs of pond snails we’d added were already proof that the pond was becoming a home.

I have made several ponds since and witnessed the heart they bring to a place, so this year we decided to act on our ambitions at Hillside. I worked up a measured drawing to test the levels, but we laid it out by eye on the day so that it responded to the place. Ponds should always be bigger than you might think because the marginal growth can diminish the scale of the clear water by as much as a third. A pond should also be deep enough to retain the cool temperatures you need to minimise evaporation and discourage algal bloom. We were aiming for two metres of depth, but we had to stay above the level of the stream that runs below the pond so we managed about 1.5 metres. Deep enough to swim on a hot day and we hope to keep the water stable and the balance in place for the ecology.

We wanted the pond to not only feel like a natural culmination of the hollow, but for it to also retain the water with a ‘natural’ liner. By digging a test pit three years ago we’d found the clay there was not consistent enough to puddle the pond. Puddling is an old process of breaking down the clay structure by driving animals over it to pummel the base so that it holds water, but in order for it to work you have to have clay without impurities. Our clay, we found, had gravel seams running through it that would make puddling impossible.

In sites where there has been the right access and clay nearby, I have imported clay to avoid using butyl liners, but it was impossible here with our narrow access and steep slopes so we opted to use a bentonite liner. This is a manufactured fabric that suspends dry bentonite clay particles within a geotextile sandwich which is laid out like a carpet over the base of the pond. When hydrated, the bentonite expands and seals to form a waterproof lining.

We had to wait for the weather to be dry enough to have a clear run at the excavations. The topsoil was stripped over the area of the excavation and moved up the hill where we will eventually extend the barn garden. The next layer of subsoil, which we found to be ‘clean’ and free of stones was put to one side so that it could be spread in a 300mm layer over the liner to protect it from damage. The excavations ran for longer than we’d hoped with our slopes and rain making access impossible for a few days in August, but the rough shape was in place within a fortnight. We made steeper sides into the water on the long sides to discourage marginal growth and open up views of the water, with shallow shelves about 300 mm below the water surface where marginal plants would be allowed to colonise at either end.

A trench was dug along the bottom of the pond for a land drain which will take away any spring water that might put pressure on the liner from beneath and then a layer of sand was spread over the pond base to cushion the liner and prevent any stones potentially puncturing the seal. The liner, which came on 4 metre wide rolls, was immensely heavy and took some manoeuvring with a fork-lift and four men to heave it into position. It was then folded into a trench around the perimeter to hold it in place. A spill, where the water runs over a depression in the margin, takes any excess water away in a little swale into the stream so that the course of the water is continued.

Over the years of watching the springs that run in the ditches by the hedges, it became clear that the spring that runs from underneath the old milking barn on the hill above would be enough to charge the pond. We used salvaged stone that I’ve been saving over the years to build a head wall on the rim of the pond from which the spring water would issue onto a splash stone. A simple stone chute channels the spring water into a depression in the splash stone which gives the water an acoustic value rather than it moving through silently. The puddle in the splash stone has quickly become a washing place for the birds.

To fill the pond once the groundworks were complete, we tapped the fast running flow in the ditch that runs to the other side of the pond. It filled over the course of three days, with reflections we’d previously only imagined being caught and held there; the roll of The Tump as you look up towards the east, glimpsed views of the buildings on the hill as you look west and, in reverse, the trees of the woods which are now caught in colour that we have only ever seen in shadows on the slopes.

If the pond could have been bigger we would have made it so, I know that already, but it sits well in the hollow with the banks that rise to cushion it. It is said that the defining factor between a pond and a lake is that a lake is big enough for a swan to land and take off. We imagine that this will be a pond and that feels right here, held in the land form and with nowhere else to go.

We will not stock the pond with fish, preferring to see what arrives on its own from the ditch water and the existing ecology nearby. I do not plan on planting the pond until the growing season opens again next year, as aquatics need to grow into a season to take a hold rather than sitting cold as the season wanes. The aquatics are important though and they will help to balance the ecology in the pond so, on the 4th of September, a week after the water brimmed and wicked the margins, I sowed the land that had been disturbed in the making to heal the scar. A marginal mix of wetland natives from Emorsgate Seeds and, where we know the ground will sit damper, the Cricklade North Meadow Mix (hopefully with Snake’s Head Fritillaries and Meadow Rue), from the SSSI water meadows near Cricklade.

Whilst I was sowing the seed and with my head in an entirely different future that morning, Huw took our beautiful dog Woody to the vet as he’d been under the weather in the days the pond was filling. Neither of us knew on that Saturday morning that he wouldn’t return and that he had had his allotted time, but within a week that seed was showing green and we’d had the magical visitation of a never-before-seen kingfisher. New, unstoppable life and an alchemy we are lucky enough to be part of and nurtured by.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 9 October 2021

Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

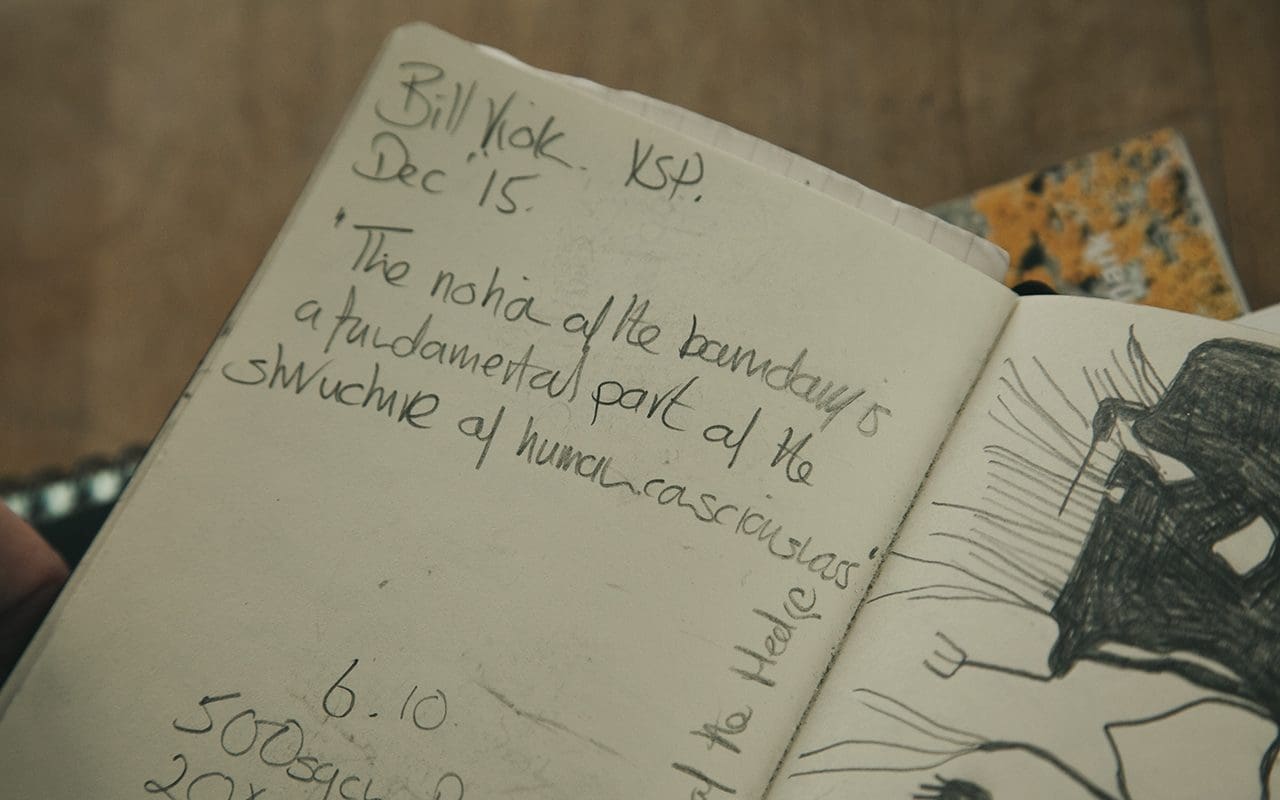

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

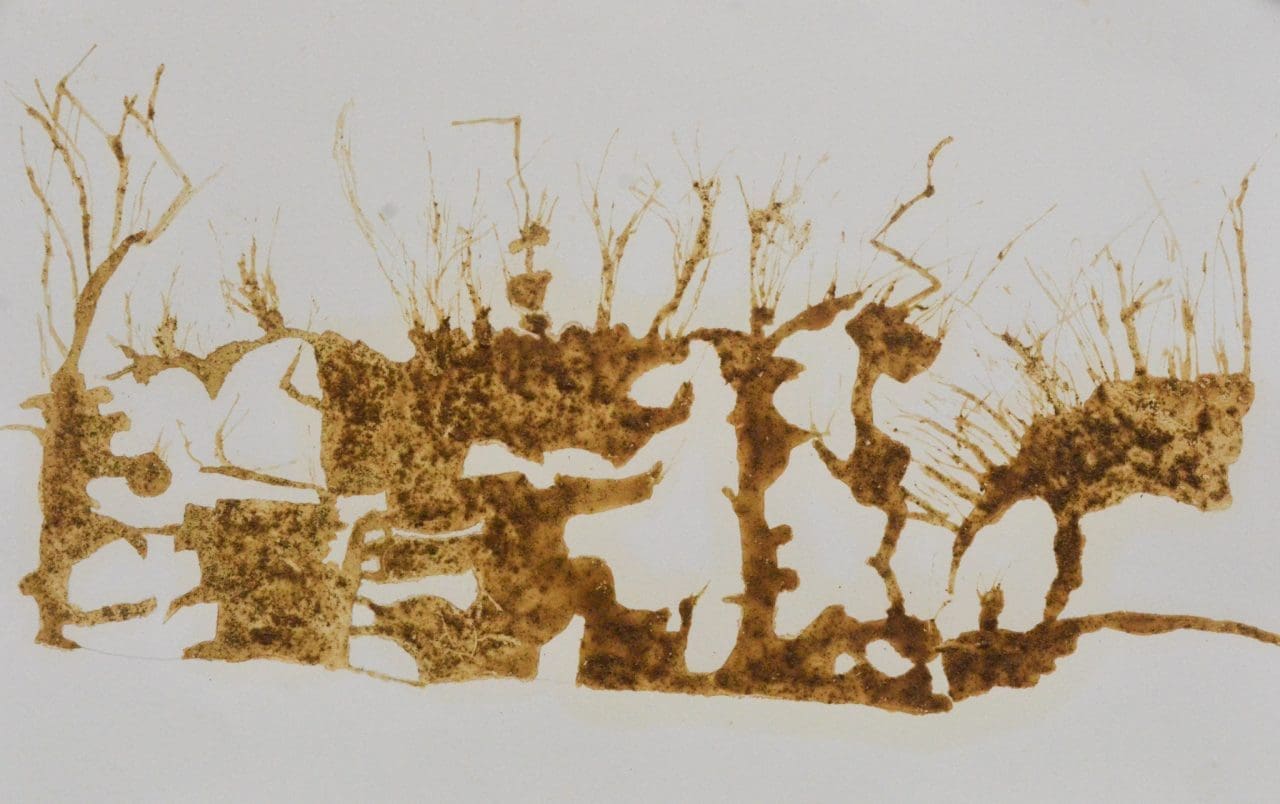

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

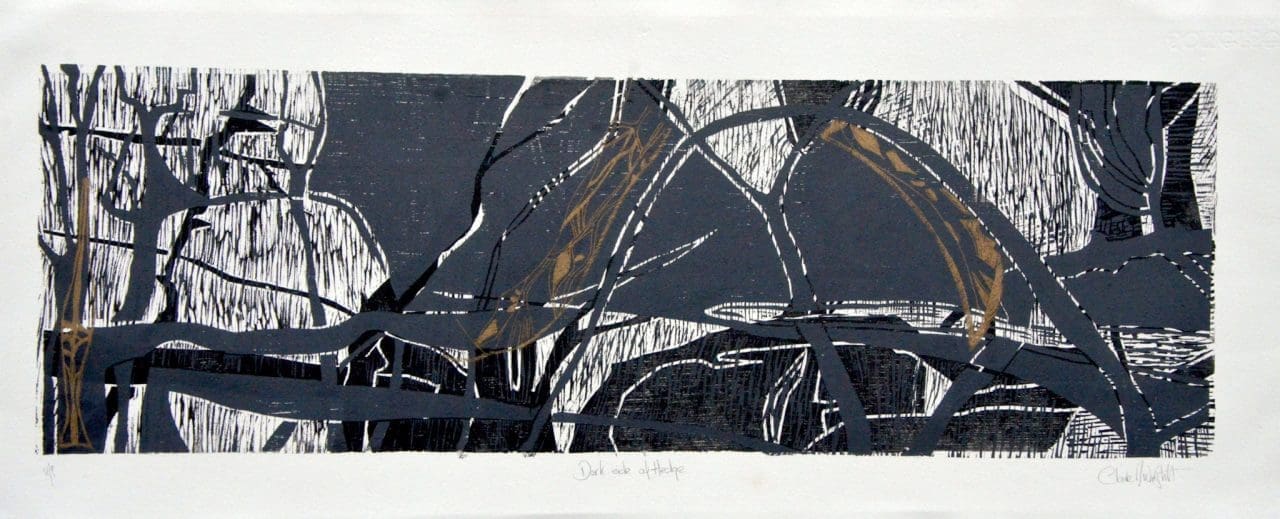

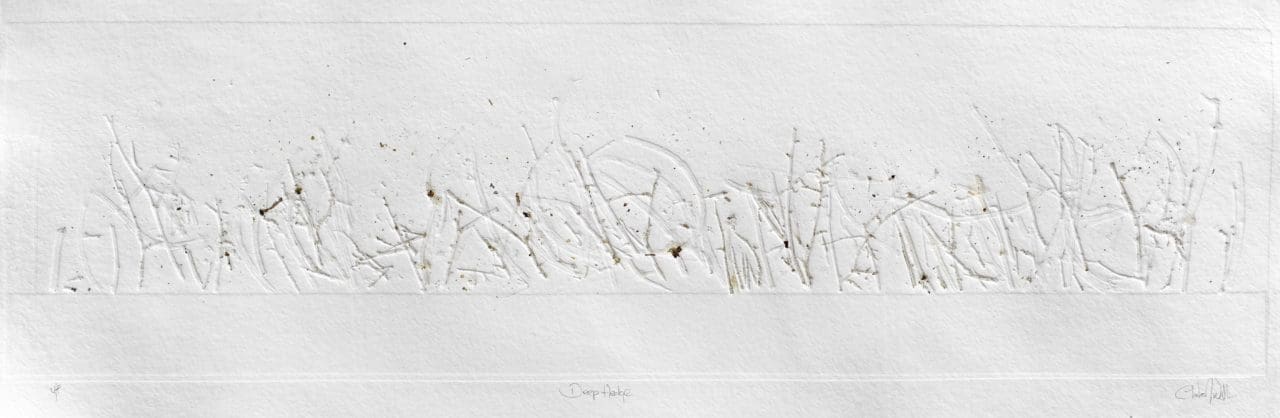

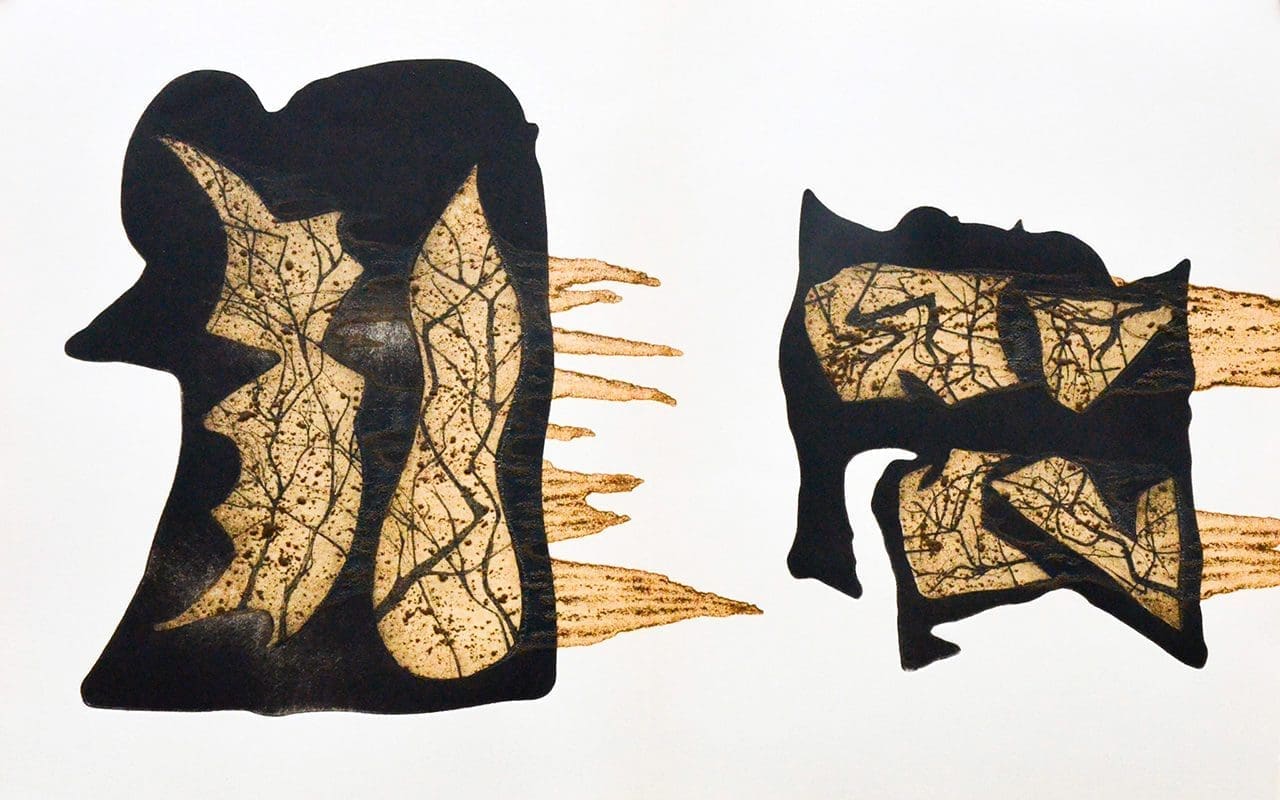

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

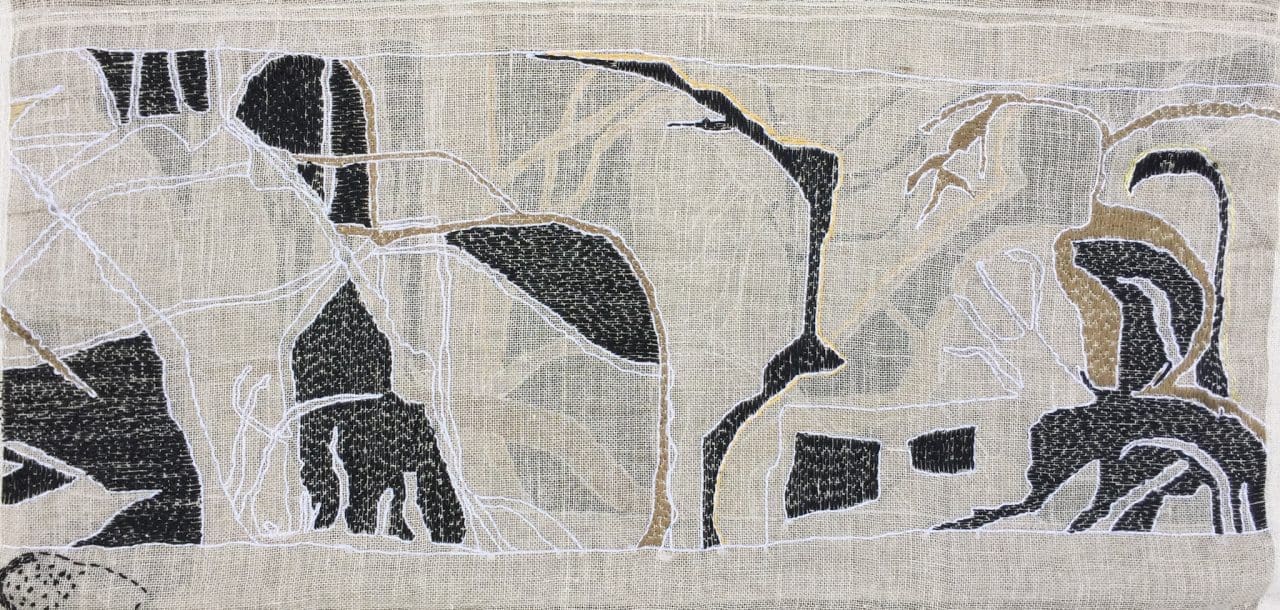

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

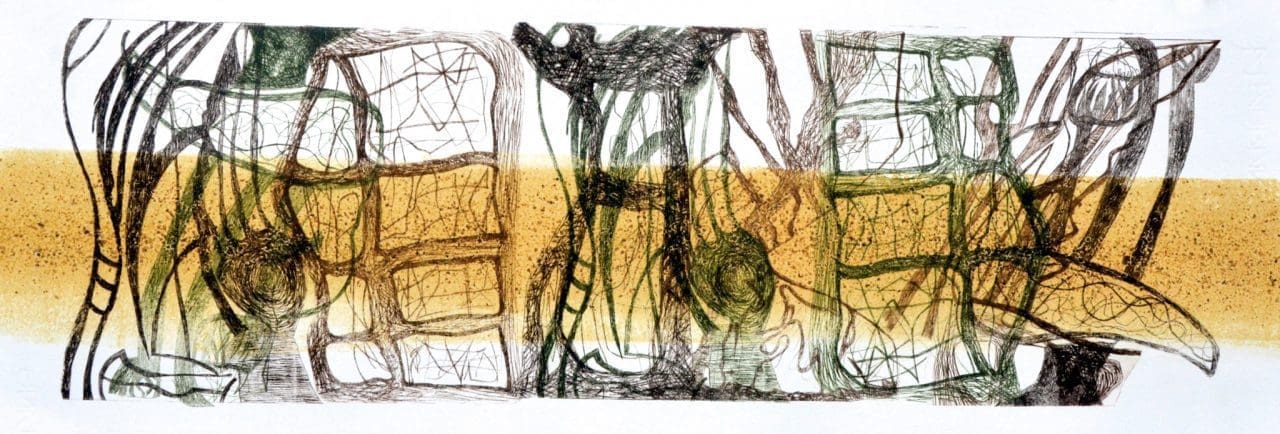

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

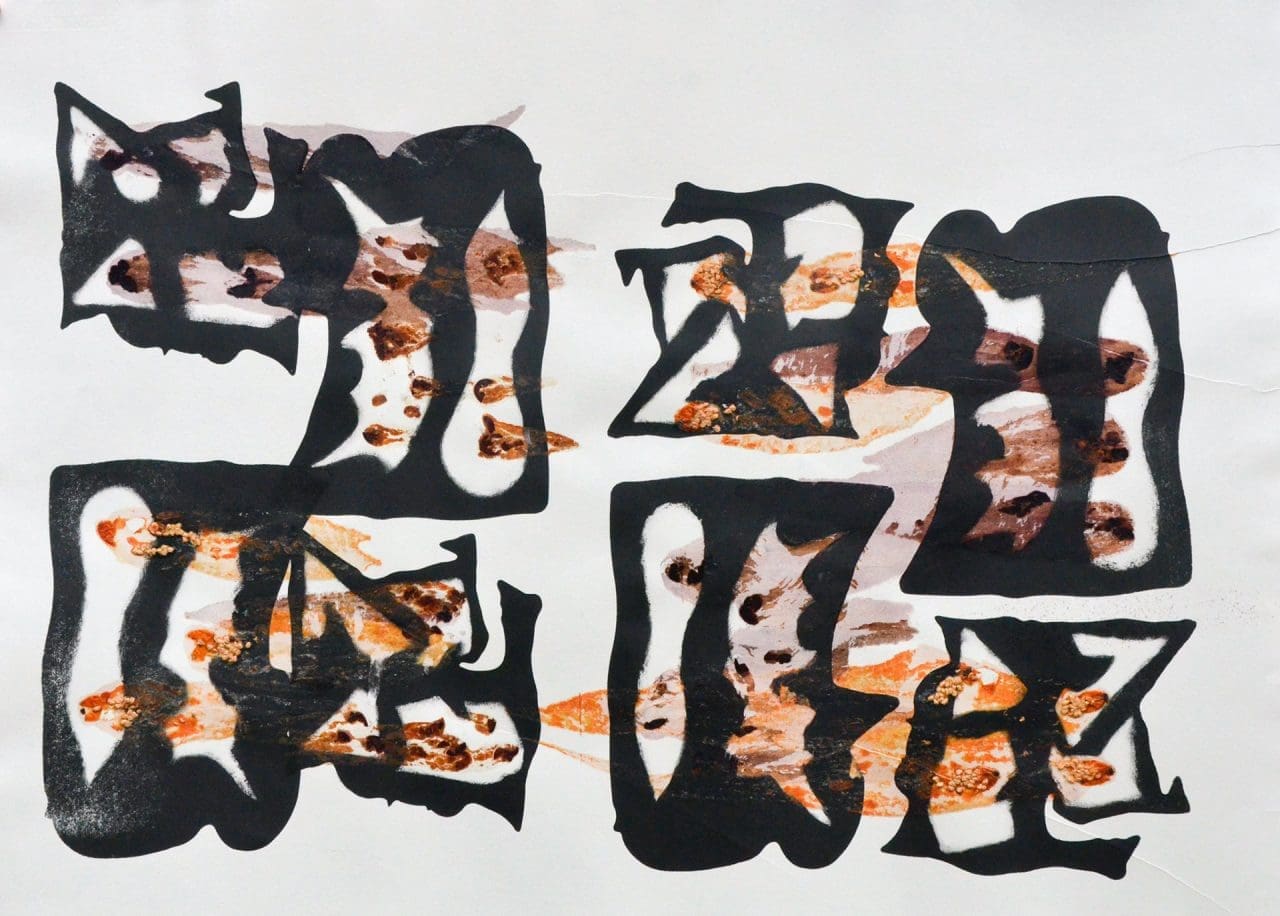

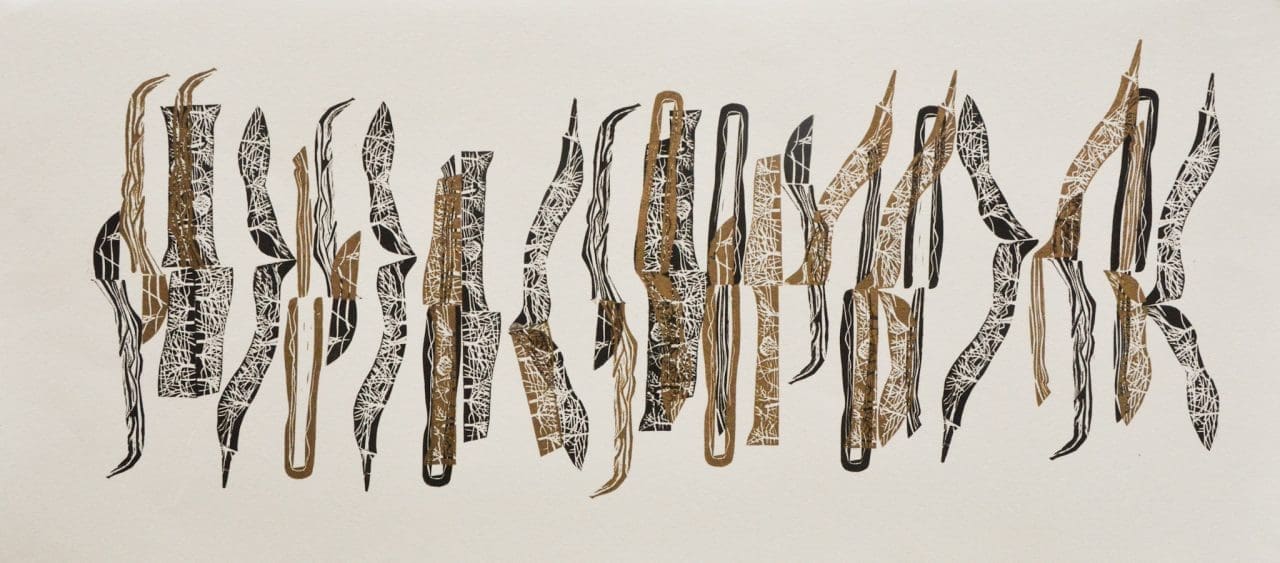

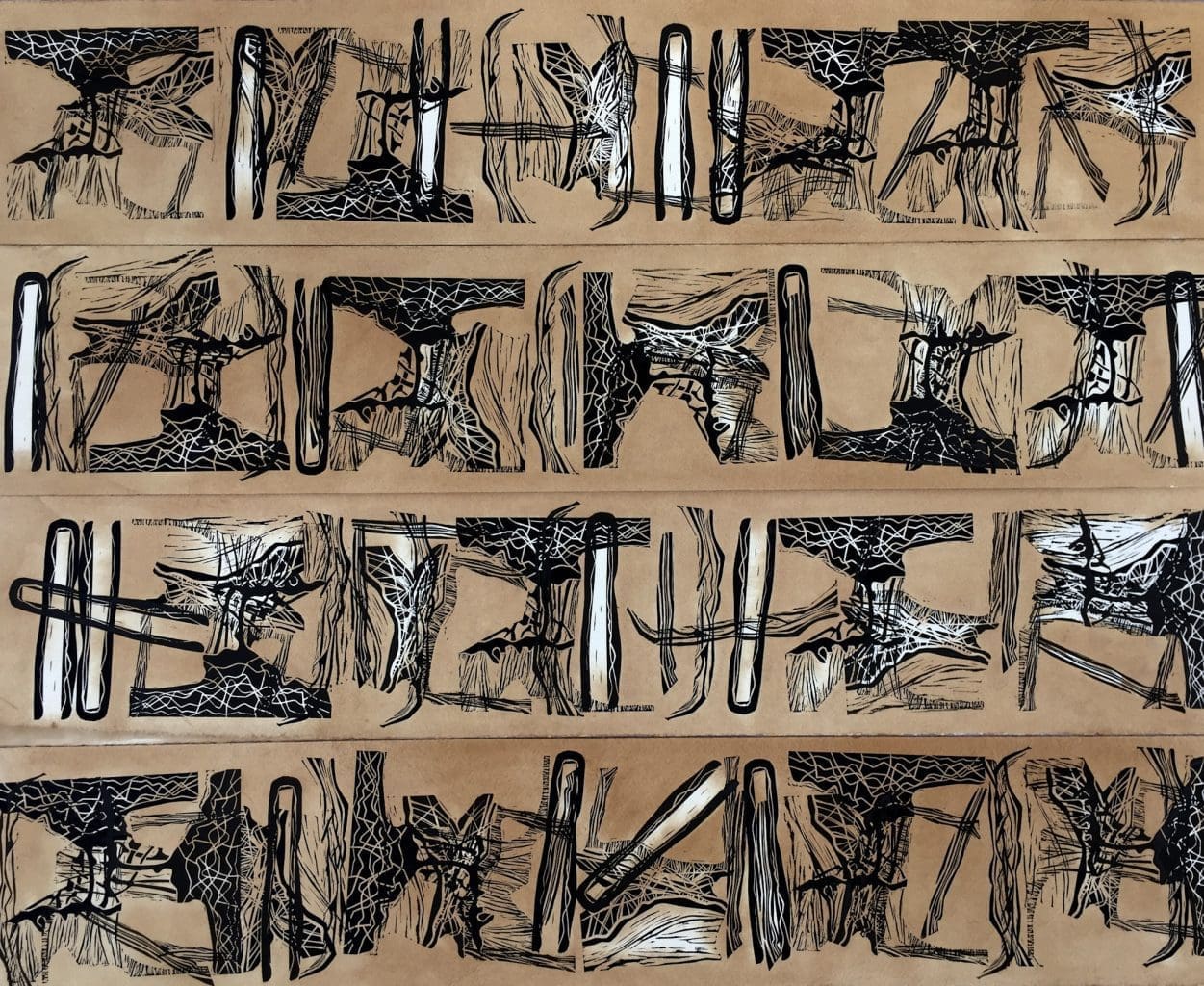

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

Cleo Mussi is a mosaic artist who worked with Dan on one of his first Chelsea Flower Show gardens in 1993. Her work is concerned with the influence and importance of nature, man’s place in the ecosystem and the effect we have on it through such practices as intensive agriculture and genetic modification. She brings a critical, politicised and humorous eye to an old folk art tradition.

You originally studied textiles at Goldsmiths. Can you tell me how you arrived at working with mosaic and the connections between these different materials ?

In the late 1980’s I was creating wall pieces using a number of textile processes, printing, weaving and patching together found (essentially affordable) fabrics. Charity shops, car boots and skips were an Aladdins’ cave. I was also studying ceramics at night school. When I left college I began to explore mosaic as a technique and taught myself through trial and error. My work is created from second hand table-ware and ornaments patched and pieced together as with the textile tradition. Originally I wanted to make durable artworks that could be created for both interior and exterior spaces though, due to our climate, very low fired ceramic is not suitable for outside, so all my pieces are interior now.

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

You worked with Dan on one of his early Chelsea Flower Show gardens. How has the market for your work changed since then ?

My work has evolved very slowly over the years. When I left college, my contemporaries – the YBA’s from Goldsmiths – were having their first Frieze show and I was making hundreds of tiles and glass mounted works, some of which I exhibited in an architect’s office on Brick Lane and also in an empty shop in Hoxton. I had a studio on the Old Kent Road and then later at the South Bank.

In 1992 I was lucky to be accepted for a show at the Royal Festival Hall called ‘Salvaged’ and was then offered a subsidised studio. It was a fantastic space full of makers working in a variety of disciplines inspiring and helping each other. I think it may have been the ‘Salvaged’ exhibition and subsequent press coverage that introduced Dan to my work. It was Dan’s second Chelsea garden, very vibrant and rich with intense colour, and I think the mosaic complemented the planting. It was a real education seeing him create and plan a show garden and being on site during the event. I still have a number of plants that he gave me when he dismantled the garden and they remind me of that time. Plants, like china, hold memories and connect to people and events.

Since then my work has evolved in that my projects are more ambitious and my work is more refined in the making and the conception of the ideas. I create large installations of up to 90 mosaics for new touring shows on grand themes that I am passionate about. Interestingly my clients are still the same sort of people, individuals and establishments that love the work for what it is, for what it is made from and the inherent properties in the china, for the memories they revive, and for the stories that I tell.

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

Nature is clearly a very important theme in your work, and I know that you are a keen gardener. How do nature, gardens and plants inspire your work ?

I had my own small patch as a child and gathered euphorbia milk and strawberries for my dolls. At an early age my mother taught me about plants; that rue can cause blisters due to photo-allergy and that monkshood is deadly. My mother loved and feared plants. My parents’ oldest friend was Roger Phillips the photographer, ‘Wild Food’ author and mushroom hunter, so this was all part of my childhood. And that Darwin ruled, OK !

My father was an engineer, which is why I love structures and cause and effect and my mother was a human biology teacher, Naturopath and keen gardener. Plants were to be respected, but entice us to take advantage of them to keep the species alive and they in turn take advantage of man. I collect plants like old china, gathered at every opportunity, divided, seeds collected, cuttings taken for my own garden and lovely meals made from produce either grown or from the hedgerow.

Cleo in her garden

Cleo in her garden

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi. Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

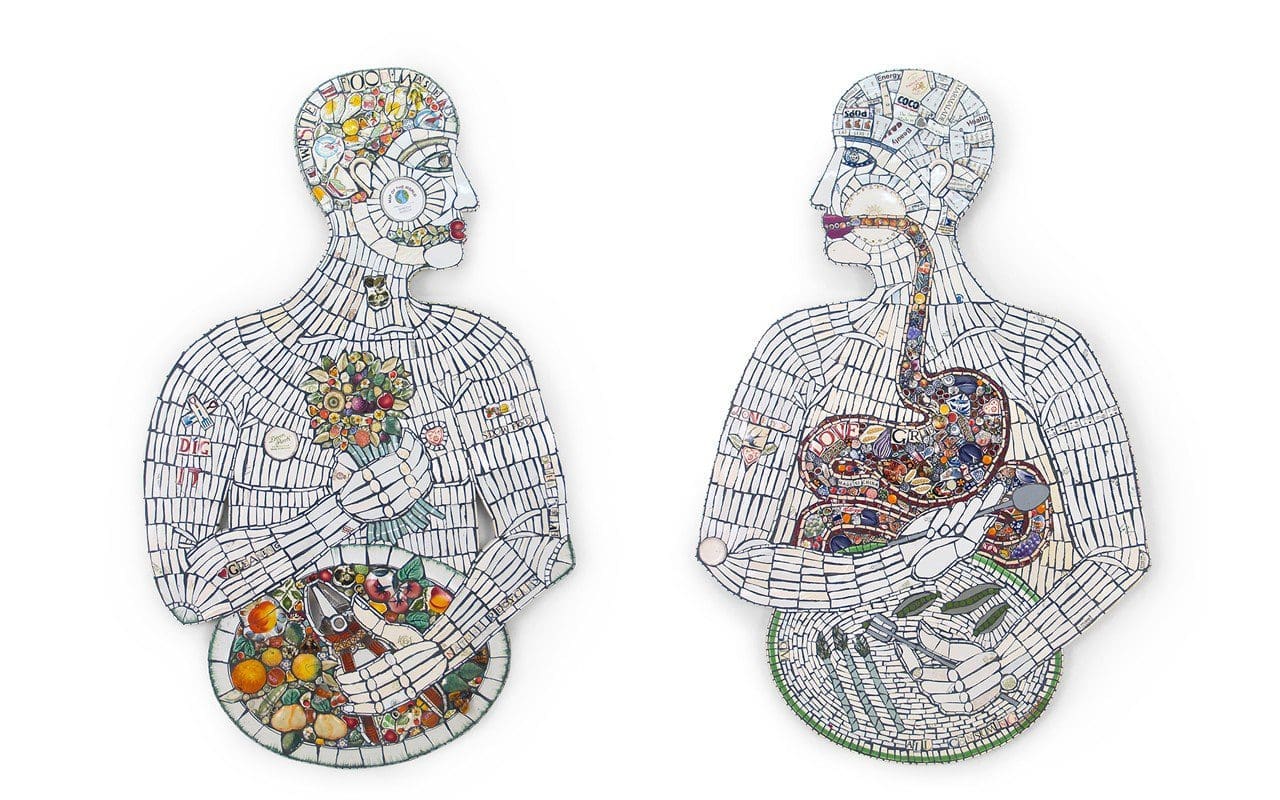

Can you tell me about your recent conceptual shows ‘Pharma’s Market’ and ‘All Consuming’, the themes you explored through them both and why they are important to you ?

These exhibitions connected ideas about food, agriculture and animal husbandry with modern developments in stem cell research, genetic modification and alternative energy. I am intrigued by evolution from the microbial soup in sea vents to archaea, bacteria, viruses, plants and animals; the physical details, the names and the stories and connections on the cellular level. These exhibitions explored the history, the characters, plant hunters, collectors and science. I observe man’s destruction and consumption of natural resources and the impact on our environment, whilst being inspired at the creativity and imagination to solve problems. For example, most recently the discovery of mycelium that neutralise toxins in toxic waste or that bind clean plant waste to form biodegradable packaging, or fungi that help in cancer research. More recently I have become interested in cyborgs and biophysics as well as in the Human Brain Project, the Human Genome Project and, of course, the microbiome; the little gardens in our own bodies yet to be discovered.

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

How has your work changed and developed since you first started ?

When I first started making mosaics, my work was quite simple: tiles, tables, abstract wall panels, naïve faces and fountains for conservatories and gardens, I contributed to many gardening and craft books. Currently my work is generally exhibition focused with a number of commissions alongside mainly for private individuals, but also for arts centres and hospitals and businesses. The pieces are figurative and tell a story. I often have dark tales to tell, but with twists of humour, layers and details hidden beneath the surfaces.

You made a research trip to Japan a few years ago. What did this bring to your work ?

As a family we went to Japan for 4 weeks as my husband Matthew Harris (also an artist) and I were due to create a joint touring show called 50/50 starting at The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath. It was a fantastic experience, and refreshing to develop new work purely from visual information. We were inspired by very different things, but both of our work is constructed from fragments. We incorporated our research and inspirations. In the final exhibition, which unified the work, we had cabinets of sketchbooks, objects and photographs. We visited many of the moss gardens and temples as well as contemporary art and cultural sights. It was from Japan that I developed my interest in Kawaii and Japanese spirit creatures which include such unusual characters as fire-breathing chicken monsters, a red hand dangling from a tree, the spirit who licks the untidy bathroom and other inanimate objects that come to life.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Outlaws – Wanted Dead or Alive, 2016. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Your work clearly engages with the history of mosaic craft as a means of storytelling. It also appears to increasingly be concerned with political or social themes.

I think of myself as a modern day folk artist. In the traditional sense of Folk Art my work reflects the world that we live in whilst connecting to bygone days. The mosaic technique is simple, but the content has depth. The work can be read on many levels and I often touch on word play and double meaning. The work on one level is purely decorative celebrating colour form and pattern and, alternatively, on another level has a political content.

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

What are you working on at the moment ?

I am creating a new touring show which I hope to take to London as well as nationwide. The ideas are in their infancy, but I am looking at how weeds have evolved and the relationship between them and man’s migration and establishment of agricultural settlements. I am interested in the symbiotic relationship that we have with plants and the delicate balance of what we ingest as cure or poison and what we cultivate as food or weed.

I love the colloquial names ‘Bunny Up The Wall’ (Ivy-leaved toadflax), ‘Bomb Weed’ (Rosebay willow herb), ‘Jack Jump About’ (Ground elder), ‘Kiss Me Over The Garden Gate’ (Pansy), ‘Summer Farewell’ (Ragwort) and all the Devils; claws, blanket, tongue, fingers, etc. Many of these weeds were migrants, and yet they define our landscape. I am intrigued by this language that comes from the people who worked the land, often describing the plants and ‘weeds’ in terms of endearment or loathing from their working days; knowledge passed down by example and word of mouth.

What do you find to be the challenges and differences between self-generated work and commissions ?

Time is always the master, and the work is very time-hungry to physically create. I constantly alternate between making work that people would like to live with and thus support the creation of the more challenging pieces. I alternate between smaller works, which I make in series, and the large one-off exhibition pieces that can take weeks to make. I love to take on new large commissions as these often bring new ideas into the mix that I may otherwise not discover. Recent joys were a Donkey with Baskets for Vale Community Hospital in Dursley, a giant magic cat inspired by Edward Bawden, a piece about education called ‘Ode To Ed’ at Prema Arts in Uley and a Solar Panel Installation Worker for Primrose Solar in London. Pretty diverse.

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Can you tell me about your role in The Walled Garden at The Museum in the Park in Stroud ?

‘Patron of The Walled Garden’. I am rather pleased with my new title. I have been asked to create a planting scheme on a shoe-string budget for this special space. The garden is about a third of an acre and is managed by teams of volunteers. Essentially the back garden is open at The Museum in The Park. It was untouched for over 50 years and it has now been given a new life as a place for education, contemplation and creativity for the community. Since 2008 numerous volunteers have contributed time and knowledge to this space. Starting with secret artist donations to raise funds and teams of people excavating and clearing, sifting, weeding planting and now watering. The hard landscaping and education space was commissioned and completed last year and now it’s time to put the icing on the cake. So, with just a few hundred pounds, we have purchased a handful of plants and the rest, as with my own garden, have been gleaned and propagated, split and gifted to create a new garden in about 14 sections. Dan kindly donated a huge and varied selection of irises, which have been combined with a collection from Mr. Gary Middleton, so we will have quite a show this May.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Starting from scratch enables us to make bold decisions; not to use blanket herbicides, our weeds are ‘hand picked’. We have introduced English bluebells under the mixed hedges and a wild seed mix and snakeshead fritillaries in the newly planted orchard, rather than lawn grass. The beds are divided into sections and aptly named ‘Bobbly Border’, ‘Bonkers Border’, ‘The Hot Bed’, the ‘Red Hot Bed’ , ‘The Purple Complementary’ and the more gentle ‘White Border’ and ‘Fernery’. Being a walled garden it’s a very hot space with very little shade, so this has been both exciting and challenging and it will also be interesting to see what survives through the winter. So the garden will evolve. This is our first season and the garden has established incredibly well. I think it has a secret underground water source. We are open to the public and anyone is welcome to visit. Coming up now are species snowdrops, ‘Wasp’ being my favorite, an auricula theatre, a tulip bed for cutting (inspired by Dan) and then later -fingers crossed – a bonkers display of zinnias for bedding, as well as all the other aspects of the garden in each season.

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo’s work can be seen in these upcoming exhibitions;

March 18th – May 7th

‘Pour Me’

The Devon Guild of Craftsmen

Riverside Mill

Bovey Tracey

Devon

TQ13 9AF

Mid-May for 6 weeks during the Hay Literature Festival

‘All Consuming’

Brook Street Pottery

Hay-on-Wye

Hereford

HR3 5BQ

May 6th & 7th and 13th & 14th

Select Trail

Open Studios

Frogmarsh Mill

South Woodchester

Stroud

GL6 7RA

Instagram: cleomussimosaics

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage