Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my earliest inspiration were the roses growing on the pathway leading up to our childhood house. That scent has stayed with me forever. The rose is a very powerful plant, it triggers so many memories. Like a form of time travel, it has taken me to some very magical times and places, it has been hugely influential.

Then I was inspired by learning about distilling plants with an eau de vie distiller in Alsace and connecting with herbalists such as Peter Jackson Main, Peter Conway, the work of Barbara Griggs and for sure the writing of Stephen Harrod Buhner. I urge everyone to read his book The Lost Language of Plants.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Photo: Susan Bell

You are a qualified Phytotherapist. Can you explain what that means and what the training involves?

It’s a posh term for a herbalist, to make us sound more professional. It means somebody who works with plants to heal and nurture people. We introduce nature and look at ways in which plants can help support disease, illness or just enrich people’s lives.

I trained with many naturopaths, nutritionists, herbalists and plant workers on shorter courses and then went into a full time BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Westminster. It took four years of full time training, but some of the most valuable training is spending time with the plants themselves. They can teach you a great deal.

Tell us about the range of products you produce, and the process you went through to develop them.

It all started as I was unhappy with the quality of the herbs & spices in many herbal teas and commercial spice ranges. There was (is) a distinct lack of relationship between people and the plants that they are drinking or eating. Supermarkets are littered with herbs in tea bags and boxes, but you don’t see the plants or engage with them enough. You don’t know where they are from, when they were harvested, who harvested them, you can’t even see the plants. So I wanted to create a range of plant products where you could really engage with the plant itself, on a very basic level by looking at and identifying it, drinking its qualities. It’s about engaging with and respecting nature really. I want people to see the love and hard work (from both the plant and the people producing them) that goes into nurturing, growing, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs.

We take plants for granted most of the time. Just take black pepper for example. In almost all households it is just a commodity. It’s just not celebrated enough. It’s a sensational plant, with brilliant flavour. Just take a good quality black peppercorn and place it in your mouth and eat it. Taste it fully and consider its qualities. Phenomenal.

We really want people to engage with the nature that they are drinking, eating and ingesting. All of our plants are harvested in that growing year, we know when they were harvested and by whom. We make our infusions, waters and bitters in tiny batches. It’s all created by hand with lots of care using the most vibrant plant material possible.

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

Our aromatic waters (non-alcoholic distillations of plants) were sourced from two distillers in the UK and India, although we have since stopped working with them as we are now distilling everything ourselves. There will be some very special distillates available in 2018 as we are currently working on polypharmic distillations, distilling lots of different plants at the same time. There is a natural synergy between plants in the wild and it’s always interesting to see which plants like to grow together, for example nettle & cleavers. We are trying to capture this synergy and relationship in the form of a distillation.

We distil plants in traditional copper alembic stills (main image – photo by Susan Bell) to use as a flavouring for food and drinks and as ingredients for natural skin care. We are just starting to use CO² extraction, which produces the most beautiful and vibrant oils. We also work with co-operatives in Southern India and Sri Lanka who supply us with beautiful vibrant spices. Again it is crucial that we know who harvested the plants, where and when. We visit the growers on their tiny holdings – when I say tiny they are really tiny, 1 hectare and less – and they cannot afford organic certification, so that’s where the co-operative comes in, to help give the growers the sales platform and access to people like us.

The bitters are remedies and recipes that I had been using in practice and for drinks creation for years. They cover all of my inspirations, so there is an English-based blend with 20 herbs grown here, an Indian blend with spices like cinnamon, turmeric and one of my favourite bitter herbs, Andrographis, and a Chinese blend with Chinese herbs such as Schisandra paired with a beautiful rock oolong tea from our dear friends at Postcard Teas. We wanted to share these formulas with everyone.

From where and how do you source your ingredients?

The herbs we use are mostly grown, nurtured, harvested and dried by a wonderful grower called Diane Anderson who has a smallholding in Oxted, Surrey. Diane was one of my teachers at University. She was an amazing resource and she used to come into the dispensary with the most beautiful dried herbs. Seeing these wonderful dried herbs was also an inspiration to start blending infusions.

We also work with a biodynamic plantation in Somerset, we grow a few things ourselves and for the more exotic plants, as mentioned before, we source from our friends in Southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cardamom

Cardamom

Turmeric

Turmeric

Can you explain how the bitters and herbal waters you produce might be used?

I’m not allowed to talk too much about the health benefits of our products, so broadly speaking their purpose is really to enhance and envigorate drinks and dishes and to give pleasure. The bitters are amazing just with water, or fresh juice, pre- and post-prandial, to stimulate digestive function and assimilate some of the metabolites from your meal. The aromatic waters are so diverse, I use them every day in a glass of water, sprayed directly on my face as a toner (rose), in salad dressings (rosemary & thyme are particularly good), to create cocktails with and without alcohol. They are amazing.

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

Can you tell us something of the therapeutic effects of some of your key ingredients?

Plants have endless therapeutic qualities on so many levels, physically, spiritually, emotionally, and I think it’s important that you are ingesting some good quality organic plants every day. I don’t want to say as part of a routine as that sounds boring, but use them prophylactically as a preventative. Have fun with plants, get to know them, enjoy their nature, enjoy their brilliance, it’s so rewarding for health and happiness.

The herbs we use and work with are packed full of complex secondary metabolites, diverse plant chemicals (phytochemicals) produced by the plants which enable the plants to interact with their environment. These phytochemicals have a wide range of functions, including protection from herbivores, to fight against infections and to attract pollinators such as bees and other insects. The plant’s secondary metabolites include constituents such as tannins, aromatic oils, alkaloids, resins and steroids. It is these chemicals that not only carry a raft of potential health benefits for us, but also offer a huge palette of flavours, textures and aromas to create delicious food and drinks.

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

You have a book coming out in the new year. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Super exciting, yes. It’s a book on my work really. I talk about my inspirations, some of the plants that I work with, when and how to harvest them and then how you can work with those plants to create dynamic and delicious botanical drinks. I talk about distillation, extraction methods, drying and processing the plants and then there are over fifty recipes, all without alcohol.

Would you share a recipe with us that readers can try at home?

Sure. I’m drinking a lot of sage right now so here is a simple recipe with sage including a quote from John Gerard, whose work we have been greatly inspired by, he wrote (or collated and published) the seminal text The Herball or Generall historie of plantes, 1597.

THE WISE ONE

‘Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members’. John Gerard 1545 – 1612.

Photo: Susan Bell

Photo: Susan Bell

This is a contemporary take on a classic sage preparation to produce a cooling, blood cleansing formula, which makes for a sensational afternoon tipple.

Plants & Ingredients

Sage Salvia officinalis

Lemon Citrus limon

Sugar Saccharum officinarum

Water

Recipe

15g fresh sage

4 lemons

500ml hot water

75ml lemon & sage sherbet (see below)

100g sugar

Method

Boil the water, then pour over 10g of sage into a pot with a lid. Infuse with the lid on for 30 minutes before straining into another jug or decanter. Peel 1 of the lemons and keep the zest. Add the juice of that lemon and the sherbet to the decanter and stir until dissolved. Keep the jug or decanter in the fridge to chill and serve once cold.

Serve in a wine glass with the remaining twist of lemon and fresh sage leaves

For the Sherbet

Peel the remaining 3 lemons, then put the zests in a container with the sugar and the remaining 5g of sage. Press the zests with the sugar and sage for a minute or so, then juice the lemons and stir the juice into the sugar mixture. Seal and leave to infuse overnight, or for at least 6 hours. Stir, strain and bottle. This will keep refrigerated for at least 1 month and can be enjoyed with still and sparkling water.

The Herball’s Guide to Botanical Drinks: A Compendium of plant-based potions to Energise, Cleanse, Restore, Boost Sleep and Lift the Heart by Michael Isted, photography by Susan Bell, will be published by Jacqui Small in February 2018. Pre-order here.

Twitter: @TheHerball

Instagram: theherball

Interview: Huw Morgan/All other photographs: Laura Knox

Published 30 September 2017

Clare Melinsky is a linocut illustrator, who created the cover and monthly chapter plant illustrations for Natural Selection, Dan’s new book which is being published by Guardian Faber on May 4. Clare was chosen for her keen eye for botanical detail, her innate understanding of plants and her talent for graphic simplicity.

You originally studied Theatre Design at Central School of Art. How did the change to linocut and illustration come about ?

In Theatre we had a seriously practical course with actual budgets for putting on productions with real actors. We stayed up all night sewing on buttons and painting scenery. It taught me about deadlines and responsibility, skills you would not normally associate with an art school education. And I also learned that the theatre world didn’t suit my temperament.

In the Foundation year at Central I had enjoyed a week of printing linocuts, and after I left college I did some linocut printing on textiles. A publisher friend, Richard Garnett at Macmillan, asked if he could use one of my motifs on a book cover: so I discovered the world of editorial illustration. At the same time Mark Reddy, a contemporary at Central, was starting out in advertising, and he, too, commissioned a linocut image from me. So I also discovered the existence of illustration in the commercial world. Both were much more financially rewarding than printing bedspreads and cushion covers. Light bulb moment: I would be an illustrator.

Illustration for Tesco wine label

Illustration for Tesco wine label

There is clearly a connection between theatre and the narrative complexity and framing of many of your illustrations. How do you go about identifying the elements required for a commission and then putting them together in a coherent whole ?

I have always enjoyed the research part of a job. As a student I spent many happy days ordering up stacks of dusty books from the card index at the V & A library, and sketching in the galleries. Now I have my own collection of reference books which I know inside out.

I like to get authentic detail of the time and place, and look for telling motifs rather than invent my own. For example the figure of Juliet on the Penguin Shakespeare cover is based on a tiny detail in an Italian fresco that I came across when looking at contemporary images, a lady leaning on a balcony: there was my Juliet. Having identified the elements, I then apply structure and colour and contrast to the specified size and shape in the short time available. Rather like garden design, I suppose.

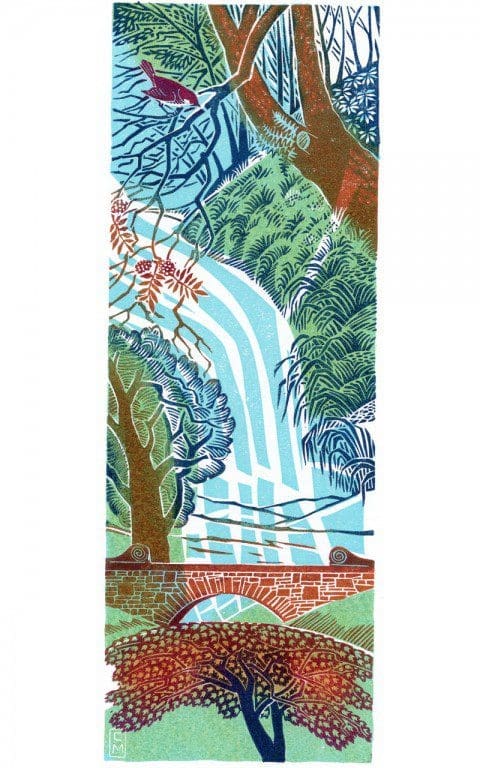

The Holm

The Holm

You have said that your work is inspired by historic woodcuts. I can see echoes of Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and others in your work, and many of your plant portraits have a distinctly Japanese feel to them. Can you tell me about artists that have inspired you ?

I am a big fan of Bawden and Ravilious. I first came across their work at an exhibition at the Tate in 1977: The Curwen Press collection. It was a seminal moment. Before that I had studied technique by looking at Bewick’s wood engravings (1800-ish) and Joseph Crawhall’s popular woodcuts from the 1890’s.

Some years later I was given a secondhand book of mid 20th century Japanese prints collected by an American, Oliver Statler, when he was stationed in Japan after the war. These prints are known as Hanga: a revelation to me. A whole new way of looking at relief prints. More recently my daughter Jessie spent two years in Japan on a Daiwa scholarship doing part two of her architecture degree. So I was able to visit her in Tokyo, and travel during the traditional cherry blossom festival time which added a lot to my appreciation of Japanese style, and prints in particular.

Seeing the gardens in Kyoto was so exciting, in the context of their temples. Our accommodation in Kyoto was in a monastery, and we were expected to meditate in the temple for an hour before breakfast, which was mushroom broth. In the hillside moss garden, we saw the monks (or were they gardeners?) picking fallen leaves out of the moss to keep it pristine.

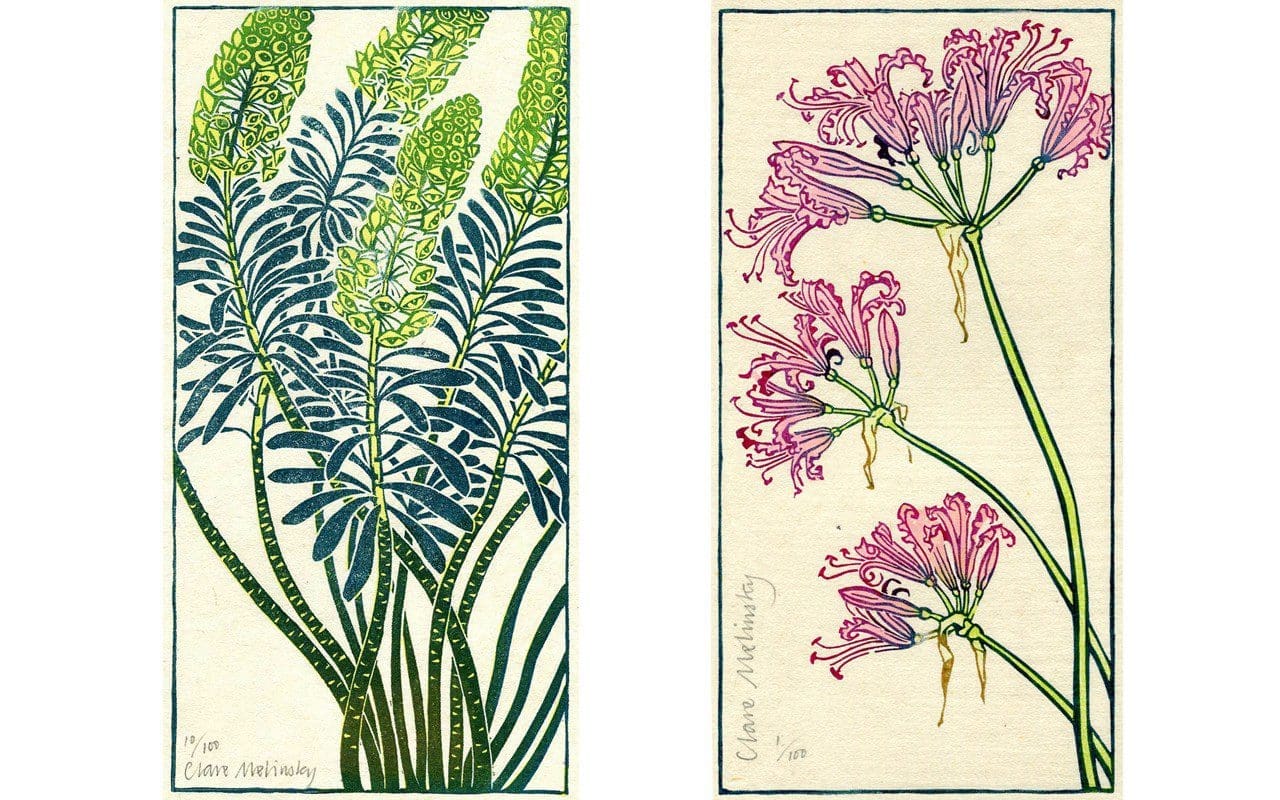

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

You have said that your garden can easily distract you from your linocuts. Can you tell me about your garden and what it means to you personally and professionally ?

After graduating I still lived in London. But my partner and I spent the summers with his sister’s young family in south west Scotland on their smallholding: we decided that was the life for us too. We started with twelve boggy acres at 1000 feet (300 metres). That means high up in the hills. We were the last house, six miles up a single track road in Dumfries and Galloway, south west Scotland. Sheep, goats, a dairy cow and calves, hens, two children, geese, a pony… we were very ignorant but it was a good life and I have no regrets.

It was originally my partner who was the gardener: we had a huge and productive veg plot, organic of course, with a big input of muck from the beasts. Very good soft fruit too. It was such a good lifestyle choice, because it meant that we could afford to live off my earnings in the early years. I could never have earned enough as an illustrator to support a family, if I had stayed in London.

After thirteen years it was time to move somewhere more sensible. Not far from our first house, but a bit nearer sea level and civilisation, we now have just one cat and a garden, with a wood at the back of the house and a burn running alongside. Lots of hardy perennial flowers and a small fruit and veg plot. Whenever the sun is warm I drop what I am doing and go outside with my gardening gloves on for a couple of hours. The climate here is so wet that you absolutely have to enjoy any fine weather when it comes.

Clare’s house and garden in early April

Clare’s house and garden in early April

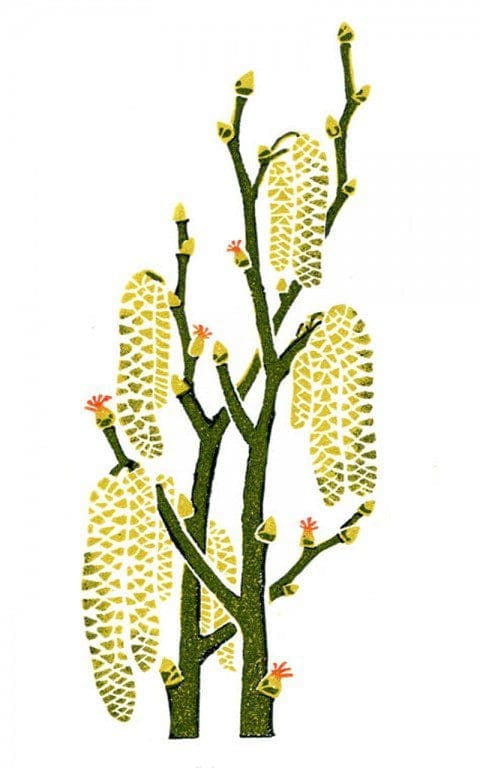

Hazel catkins

Hazel catkins

In the woods behind Clare’s house

In the woods behind Clare’s house

You work across a wide range of different media including book covers, stamps, product packaging and editorial. However, it seems that you include plants and landscape in your illustrations whenever relevant and possible. Can you tell me how your garden, landscape and plants inspire your work and influence the commissions that you accept ?

It’s what I see when I look out of the window. Most of my holidays are actually in cities by way of contrast: visiting my son Tom who lives and works in New York for example. I accept most commissions that come from my agent if I have the time: each job stimulates new ideas and creative development.

Gardening wasn’t a memorable part of childhood. I do remember individual plant experiences: a sea of lupins, as tall as us children, blue and pink and mauve, at the foot of the sand dunes on the Norfolk coast where we spent our summer holidays. A ravishing philadelphus enveloping the shed when I wheeled out my bike to cycle to school. A cataract of wisteria on an old rectory we used to visit.

My favourite toy at one time was a Britain’s Miniature Garden: little brown plastic rectangles and semicircles were the flowerbeds, dotted with holes into which you could push different clumps of coloured plastic flowers. You could buy individual flat-pack trees ready to assemble. Cardboard flagstone paths and rectangles of green flocked card with mowing-striped pattern. Little plastic rockeries and a pond and stone walls. I would save up my meagre pocket money to buy a new pack of plastic hollyhocks. Maybe that’s why I now have no hesitation in digging up a whole clump of perennials in full flower and replanting, if I decide that something is in the wrong place.

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Tulips

Tulips

Given the breadth of your commissions do you have a favourite subject matter ? Which appeals to you most ?

My agent comes up with very varied jobs – and I like that. I was so lucky to be invited to join the Central Illustration Agency when Brian Grimwood first started it. It is the one thing that makes it possible for me to live in the country, and still access the world of work in London. There is no continuity to the work, it is completely unpredictable what people ask for. The client has chosen me because they like my linocut style. So it is often more of the same. Since I finished your book I have done images for food packaging for Waitrose, a folk tale illustration for Britain magazine, and some labels for a local cider maker. Sometimes it all goes quiet and I don’t get a job for six months.

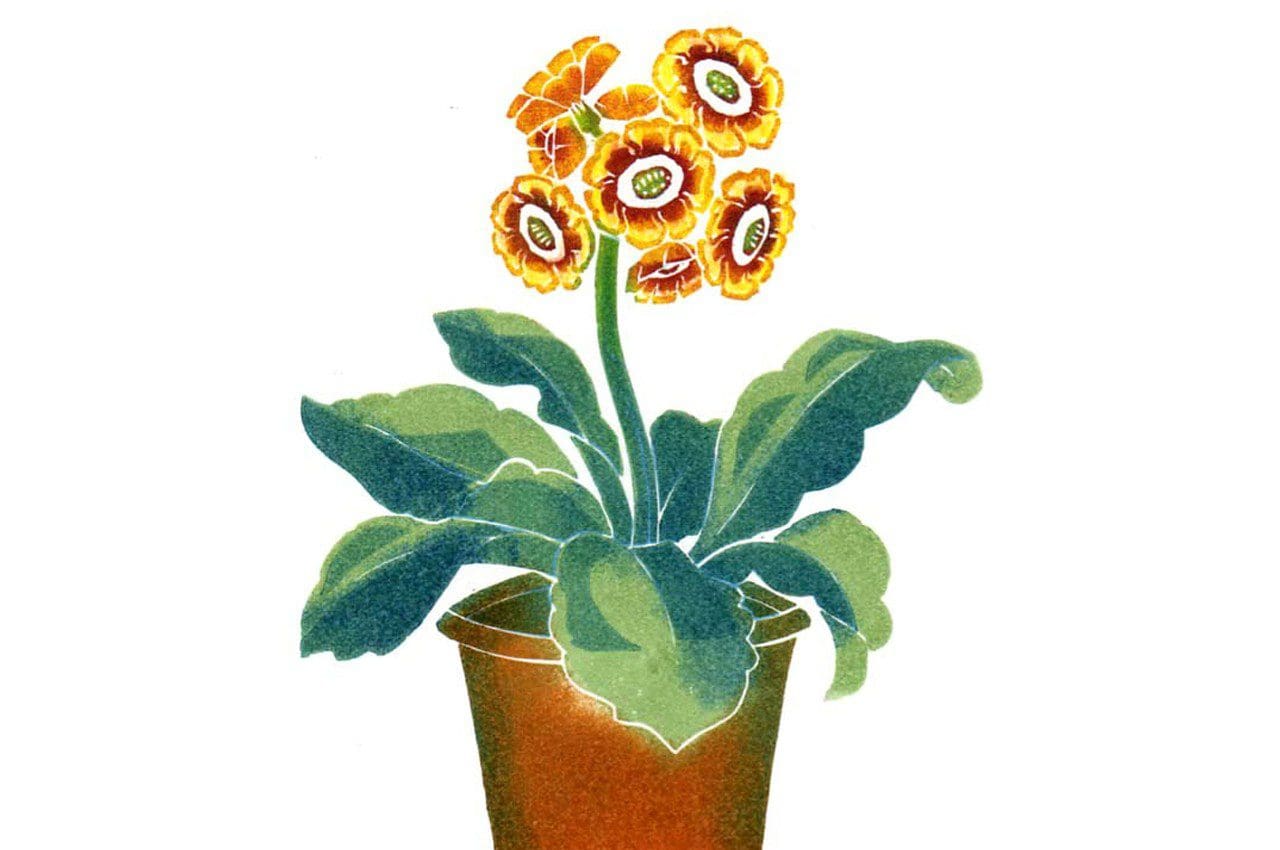

Primula auricula

Primula auricula

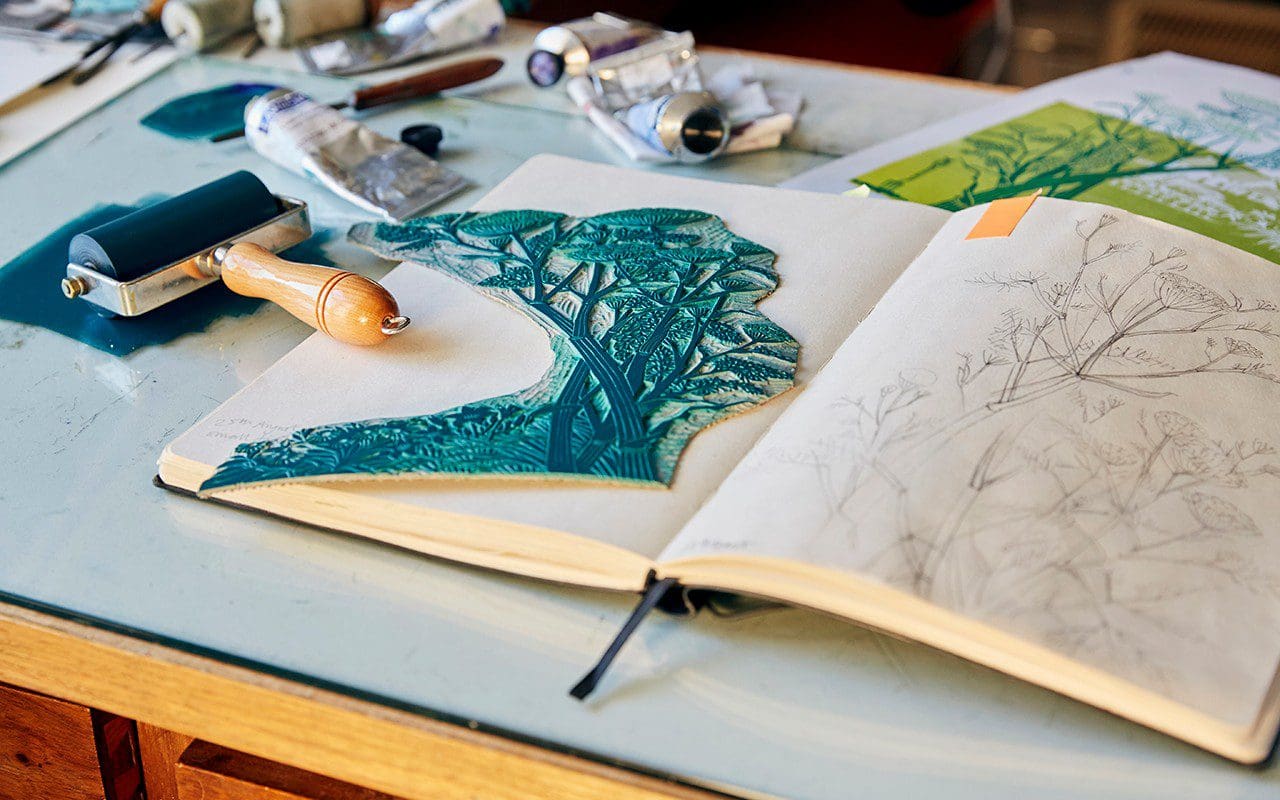

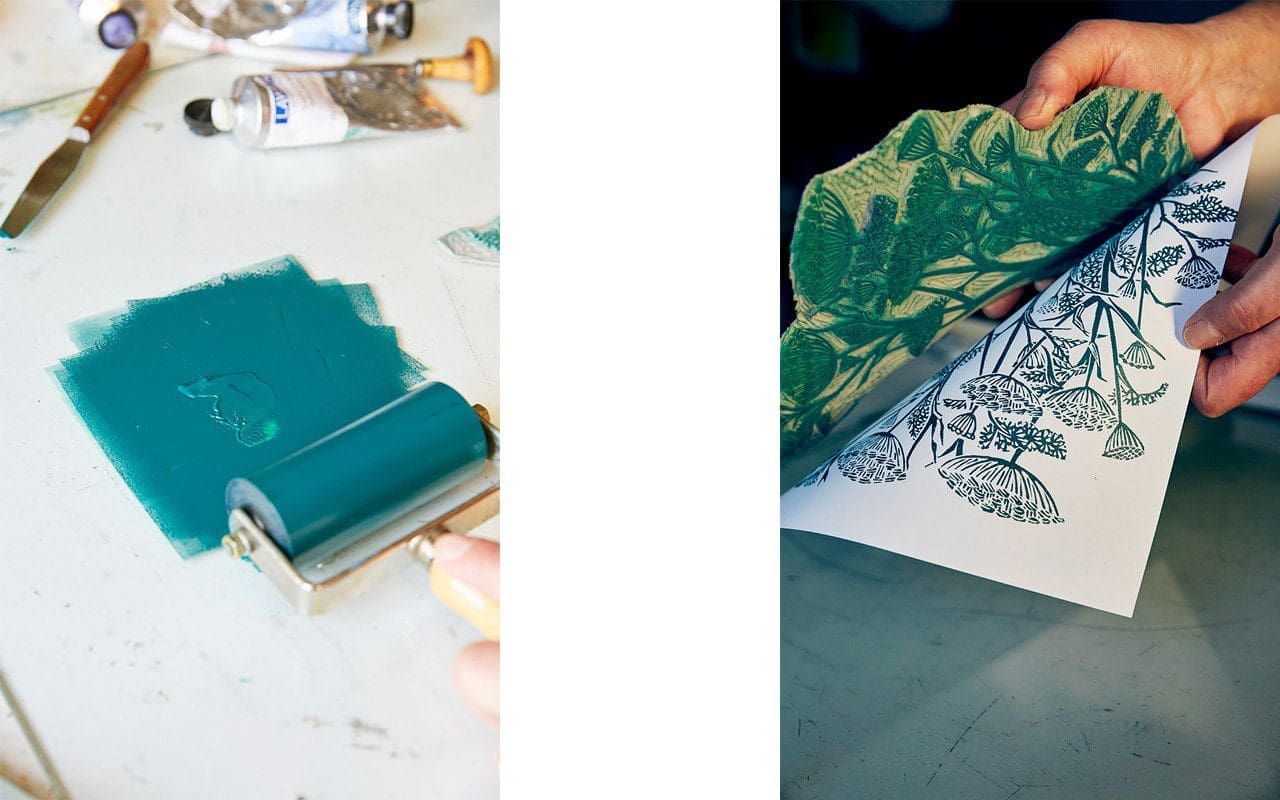

Can you explain your design process from sketch to finished print ?

I do a rough drawing to show the client. Once that is approved, I transfer the image onto a piece of linoleum. I buy my lino from a flooring supplier by the metre. Cutting a design into a piece of lino calls for simplification and clarity. I am obliged to be selective. If in doubt, leave it out.

As it is a print, everything has to be done as a mirror image. I cut into the lino with a set of five small v-shaped and u-shaped gauges. I have to decide whether to show the veins on a leaf, or the outline of a leaf, or I can just depict the solid shape of the leaf. Less is more. The areas of lino that I cut away won’t print. When I roll the ink onto the finished block, the remaining lino will pick up the ink. Then I make a print using my big press.

I can print in black and white, but mostly my work is brightly coloured as it will be used on a book jacket or for packaging. I can add more than one colour onto each block using small rollers. Where the colours merge makes an interesting blend. Then when I print a second block over the first print, more subtle and interesting and unexpected things happen. The inks can be mixed to be quite transparent, or quite opaque. I use linseed oil-based relief printing inks from Lawrence. I was introduced to Lawrence’s at art school, when they were at Bleeding Heart Yard in London. I am still using the same tools that I bought there, though the smallest v-tool has been retired and replaced: it became rather short after years of sharpening.

Making the drawn line into a cut line transforms the quality of the line itself. I am still always surprised by what I have created when I see the first print.

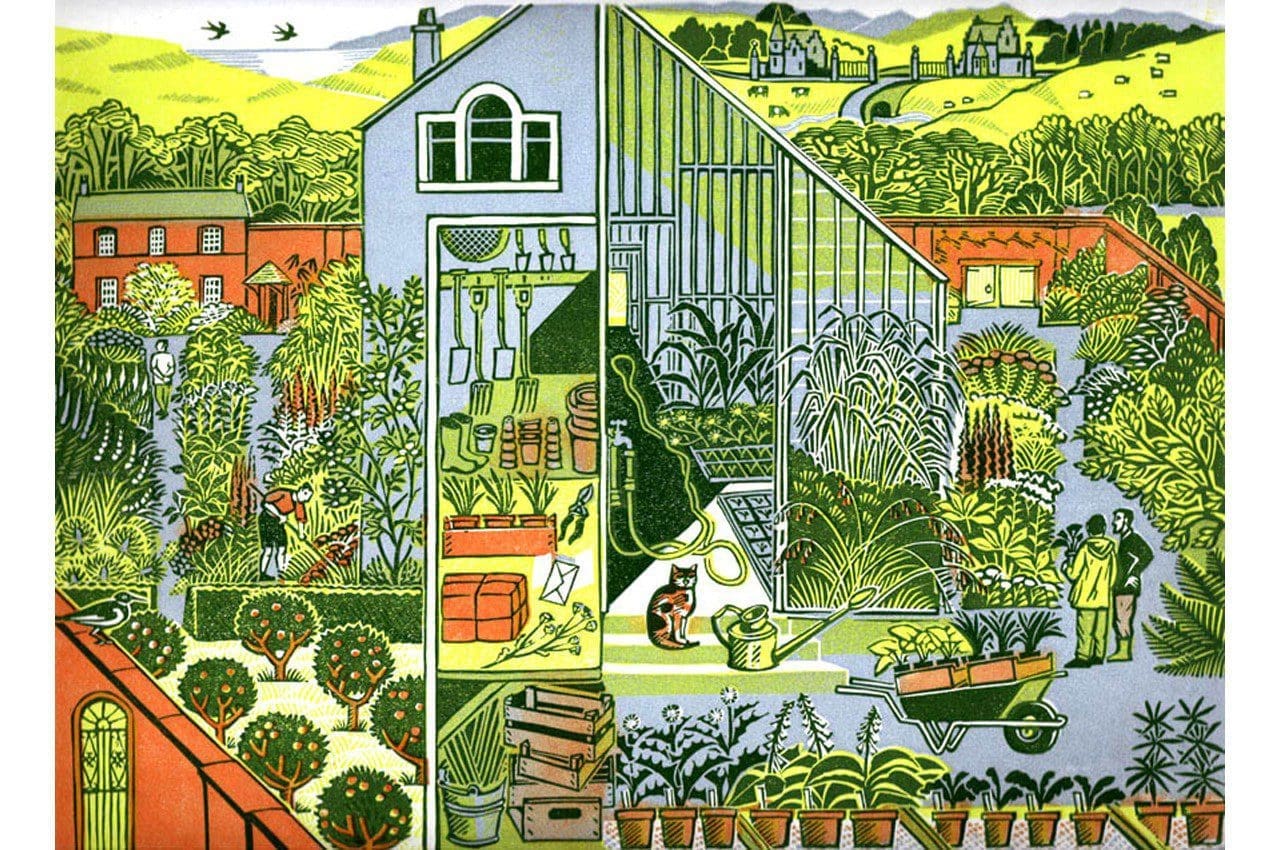

How did you approach the commissions for Natural Selection ? The cover image features a house which looks very like Dan’s house in Somerset. Did you research images of it, or is it a happy accident that it looks so similar ?

I was so pleased to get this commission, I knew right away that I would love to do the book. If the house on the cover looks like Dan’s, then that is a happy accident: that’s my house more or less. Mine actually has dormer windows, but I thought Dan’s house would look more English with ordinary smallish windows.

I first came across Dan’s name in the early editions of Gardens Illustrated when it was something new and special. And have followed his career haphazardly, since I don’t have a television, in occasional gardening magazines. Dan decided to have one plant portrait for each month. We had different ideas about which plant, but I was happy to go along with his choices. The only problem was that by then it was October, so I couldn’t draw all the plants from life which would have been preferable. But mostly I had drawings that I could refer to. I happily use photos for reference, but I still think the best work is done from life if possible.

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural Selection

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural SelectionWhat are the greatest challenges in your work ? Can you tell me about the brief for the murals at Beatson Hospital in Glasgow ? How did you visualise your work for such a large piece and how did you scale up your linocuts for the site ?

I knew my linocuts would look good reproduced at a larger size. It enhances the irregular quality of the line, the handmade look. It was exciting to see the A4 size images enlarged to two metres high, extending over four thirty metre corridors. Each corridor was named after a Scottish island as a theme, and I rearranged my selection of details of the countryside to create a harmonious and varied flow of landscape and wildlife for patients and staff to enjoy as they passed by time after time.

The Beatson is the hospital for treating cancer patients in Glasgow, and the Macmillan Fund provided money for an art consultant, Jane Kelly, to enhance the whole interior with colour and style and fittings, with the Scottish west coast as the overall theme. Very worthwhile and successful.

Each job is a challenge. The deadlines are tight. Understanding what the client has in their head is a challenge: they often know what they want, it is my job to find out what that is and turn a concept into an artwork.

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

You have produced a number of illustrations for Cally Gardens over the years. It was a shock to hear of Michael Wickenden’s recent death in Myanmar while on a plant hunting expedition. Can you tell us about your relationship with Michael and the nursery ?

Michael’s fantastic nursery is an hour’s drive along the coast from here. He had bought a derelict walled garden thirty years ago and filled it with his vast collection of plants over the years. I was there doing a drawing for the Garden History Society. On seeing the final product, Michael asked if I would do a design for him to use on his Cally Gardens mail order brochure. We became firm friends, and the brochure has been published every year with my cover design. Until this year.

It is so sad that he is no longer with us, but I firmly believe he would be delighted to have died on top of a remote mountain on a great adventure. He knew that he was taking a big risk going to these remote places, and loved the expeditions, traveling with native guides under extreme conditions. As I tidy up my flowerbeds after the winter, I can recognise each plant that came from Cally, and I am reminded of Michael each time.

He was very outspoken and didn’t mind causing offence, objecting at every opportunity to the Plant Breeders Rights nonsense. I also learned from his example that my flowerbeds should be rigorously tidy in March. His garden looked like a jungle by the end of the summer, but in March everything (well no, maybe not everything, it’s a huge area) was cut back and isolated into its own distinct space. We all hope that some gardener with vision will grasp the nettle and keep the place going.

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

What are you working on at the moment ? What would be a dream commission ?

Just now I am designing a publicity image for an exhibition for the Royal College of General Practitioners. Then I have to print up more work for my local Open Studios event 27th-29th May 2017. I also teach linocut workshops, including residential courses at Higham Hall in the Lake District three times a year which I enjoy.

A dream commission: Natural Selection in an Italian palazzo with a cook and a housekeeper and a gardener. In the sun, with a swimming pool. With a whole year to do the work, so I could draw each plant from life. My partner and children and friends, and my agent, would come to visit at intervals… Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Marcin Rusak is a London-based Polish designer who explores themes of consumption, ephemerality, aging, decay and longevity in his work. For very personal reasons he has chosen to work with flowers in a range of different ways. I recently met him at his new studio where he talked to me about his history, his process and his creations.

Tell me how you arrived at this way of working with flowers.

It was quite an adventure for me to get into the Royal College of Art. It started with me studying European Studies, not liking it, doing interior design on the side and trying to get into art school in Poland. They didn’t accept me. So I tried the Design Academy Eindhoven, the conceptual design school, not knowing at all what conceptual design is. I was supposed to be there for four years, but after two I felt I wanted to experience more, and the way Dutch education works is they wipe your head clean and they inject their tools into you and after four years you’re only allowed to use those tools. So after years of study I knew that I wanted something more. I wanted freedom, so that’s where the RCA came into the picture.

At the RCA you’ve got this amazing ability to make mistakes all the time, and find your own thing. So I found my own thing through an accident again, because there was a brief to find an object that interests you, like from your past or wherever, just something that you like.

And so I found this cabinet that we had in my family house, which was from the 17th century. It’s a Dutch cabinet, and it’s carved in wood, and the whole sculptural decoration is inspired by nature and the seasons. So I just started investigating, ‘Why is it that I like it so much ?’. So the first natural step for me was to go and investigate nature and flowers – the subjects of the carvings – and I went to a flower market for the first time. And that’s where I started seeing all this waste. And because I was always interested in processes, I took the waste material and started doing everything I possibly could with it, to get somewhere, not really knowing where it was going. And that’s how I discovered printing with flowers.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

On your website there is a video of you making one of these textiles. What is the liquid you were spraying on the flowers ?

Vinegar. It helps to bring out the natural pigments in the flowers, and it also helps them to penetrate the silk. I also use special silks made specifically for digital printing, because they are treated with substances which react with ink, and although the flower pigments are not inks the silk reacts in the same way and the pigments become more light fast. When I first tried with normal silk the colour only lasted about a month. These pieces are about a year old and have not really faded that much, but they will fade eventually, although they will never completely disappear. I still have all the ones I made, as it is really hard to sell things that don’t last, but people have started to understand me better now, and they are prepared to buy the idea along with the object. Also recording the process of making the work becomes part of the work itself.

By the end of this project I went to my tutor, and I said, ‘You know what? It’s actually really funny that I’m doing these things with flowers now, because I have a history of 100 years of flower growing in my family.’

When I was born the business was closing down, so maybe about two or three years after I was born it closed. So until I was 26 and at the RCA I really had nothing to do with flowers.

I was raised in those abandoned glasshouses. That was my childhood playground. It was amazing. I still have this memory of the very dry warmth when you were in the glasshouses, but there was nothing else, just these pipes coming out from everywhere, and all these steel structures, but no flowers, no natural material. And then we moved when I was 10. My mum always loved flowers and she always wanted to do something with them, but she never did.

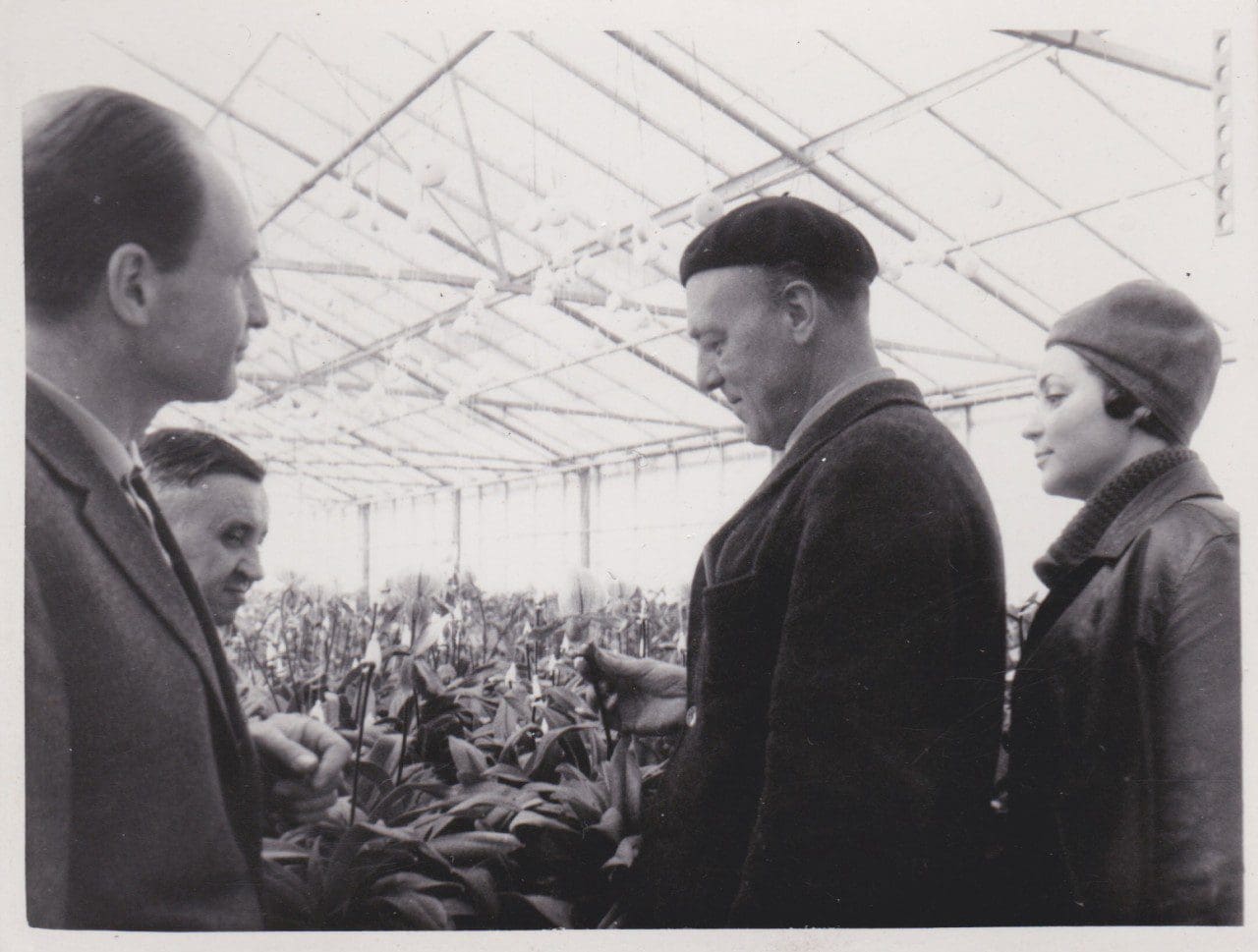

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So the flowers weren’t really in the family, they were in this amazing history we had, because my grandfather, and his father, for over a hundred years they were growing flowers. They also had flower stores, so they had a really big business, mostly growing orchids. And my grandfather was kind of a freako scientist, so he was really bad with people, but amazing with plants. So actually discovering this was a breakthrough for me, but it was also quite natural. Although I kill plants, or I use dead plants or I make objects that die !

But it made me think. I remember having this conversation at the RCA with one of the tutors, they asked, ‘Why are you doing this, actually ? It’s nice that its this textile that extends the life of already dead flowers by months or years, so that’s great, but what’s the interest ? Think about it. Why ?’

So then I started doing much more research work in the Netherlands and actually trying to understand why people manipulate flowers so much these days, and how flowers became a commodity, and how they are being sold in Tesco and grown in Kenya, and flown with planes and using water in places that don’t have water. All of the background of what people don’t know about commercial flower growing. And then I started explaining to people that it’s a bit like the food industry, that started to change 10 years ago, when we started realising how we source food and intensively farm it and so on and so on. So I established a connection with Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, right next to the massive flower market there. And I made a book about it.

So you got into the science of flowers through doing this book, which you hadn’t really thought about before ?

No completely not! Because, you know, like a lot of people I just didn’t know what the situation was with flowers being grown, because we don’t have to eat them, so we don’t really think of them in the same way that we think of food, because in a way, they are perceived as a luxury. So I started investigating it at the university and they helped me a lot. At the beginning they were very suspicious of what I was doing, because they work with a lot of big brands which pay a lot of money to get their research and I was going in there saying ‘Hey, can you tell me about this ?’ for nothing. But I established a nice connection and they let me see a few things and we started talking and I introduced to them to the idea of the flower monster that I wanted to do, which is basically combining everything we want from flowers today. From retailers, to growers and consumers, everyone wants flowers to be a certain way, either living longer or smelling better or being cheaper to ship. And in the end they should be this natural imperfection, and not manipulated so much, so for me it was interesting to think about how to put that all into one piece and start communicating it to people and make them aware.

So the idea was to create this flower that does it all. So if we play with the DNA, and if the industry keeps on going the way it is right now where we keep manipulating things, it is where we might end up. I first started talking to plant geneticists to try to understand about breeding and cross-breeding, because it is possible to cross-breed a lily with a bamboo and so on. So if you have a lily which has a stem with genes from a bamboo it can then stand on a strong stem and hold this whole creature up. But how do we get there physically ? How do we make it happen ? So we researched the plants that have the certain characteristics that we needed, so anthuriums are very light, so transportation would be easier, and bamboo for the stem, or orchids with their roots outside the plant which could transport nutrition, so the whole thing could live for months. So I started working with Dutch flower engineer Andreas Verheijen, who agreed to help me with the project, and we basically took the plant species, cut them up and put them together them as nature might. Then it was flown to London in a day. It was the weirdest thing I ever did.

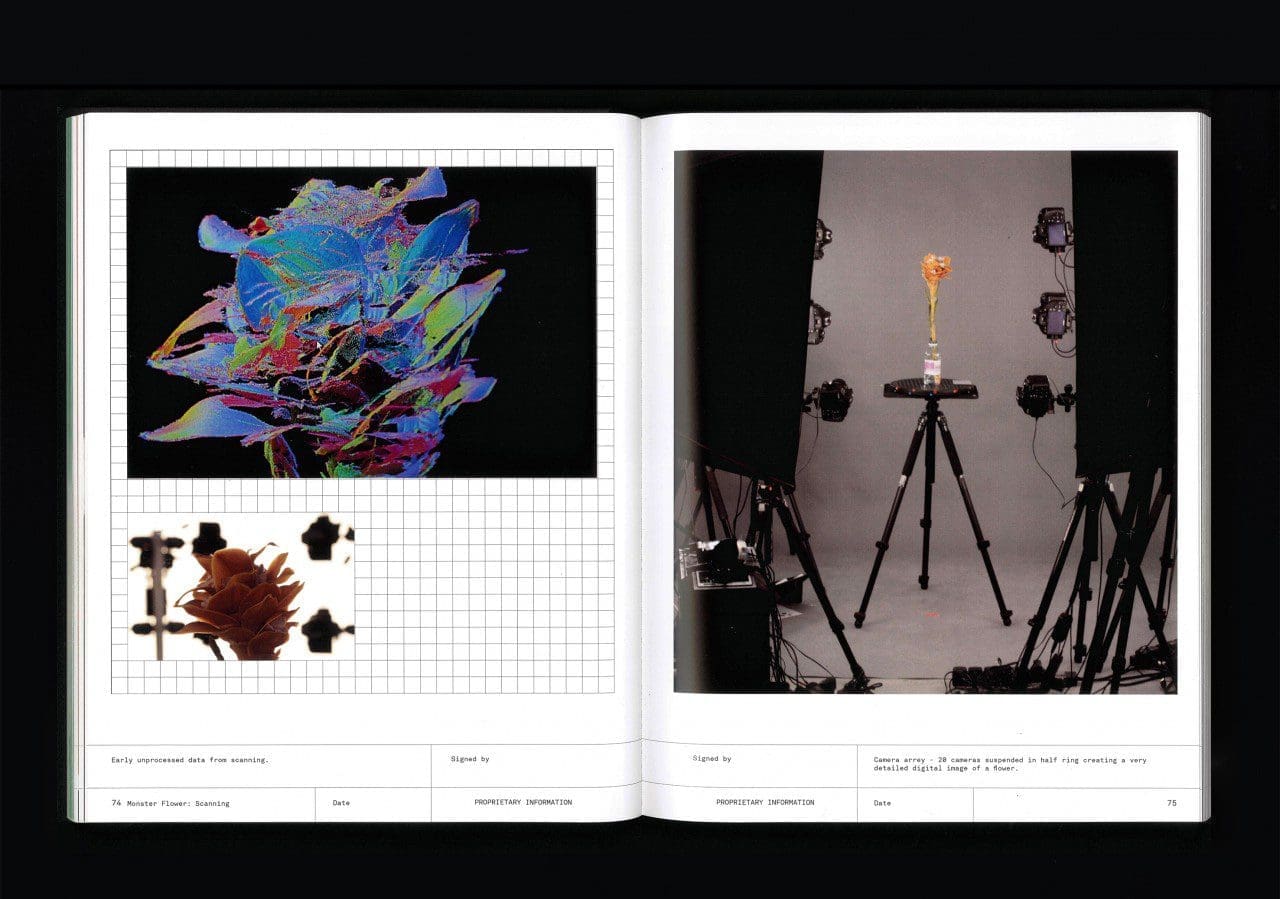

We created a number of hybrids. Each one came from a purpose. The way that they look is accidental. We were never thinking about them aesthetically. So when I came to the UK I had about a day to scan the first one. We used a camera array – 20 cameras standing in a circle. They shoot constantly while the object is spinning and they build up a 3 dimensional digital image. However, this digital file has no functionality. It can’t be printed. So I hired a 3D sculptor, Ignazio Genco, who then spent two weeks re-sculpting the digital files on a computer, so that they could be printed. The original one was made out of 22 separate 3D printed pieces, with a steel structure inside. It took 72 hours of straight printing.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

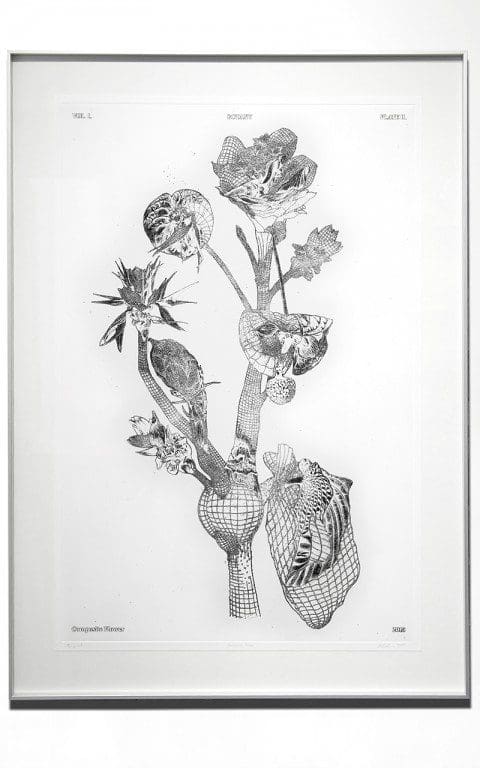

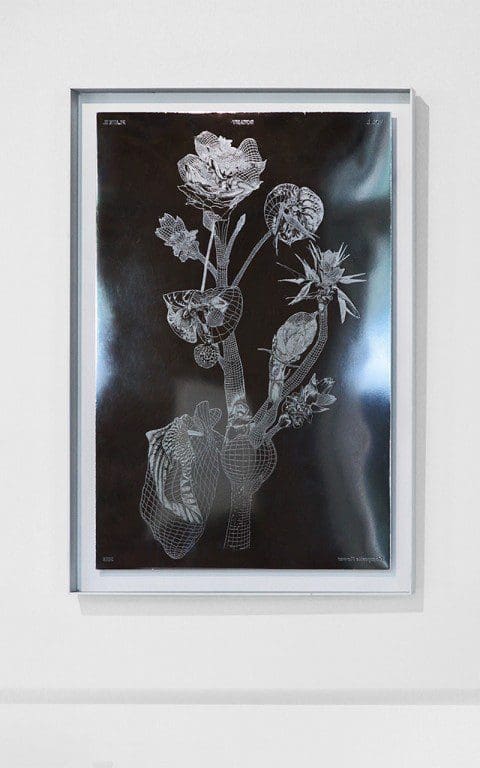

So that was the research, but I wanted to go further in telling the story. So I made these printing plates, like in the 16th century, when they discovered a new species of plant they would create a drawing of it and make multiple prints of it. So I started working with an illustrator, Clara Lacy, and we did it exactly as they would have done it, so we had the blow up details with information, we acid-etched it on copper, then we made the prints – monoprints in a run of about 15 – and then we chromed the plates to make them into permanent artefacts. I also produced a book of the whole process, as I wanted to extend the story as much as possible.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So that is how my practice works. Half of it is research, where I spend my time and money investigating what I’m really interested in, and then the other half is taking bits of it and translating it into ‘object’ work, which is where the recent resin work comes from. That all started with the research I was doing into aging materials. I was really interested in the ephemeral, the idea of value, the idea of things not being permanent.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Tell me how this vase encapsulates those ideas and values.

We have so many things around us that we don’t really necessarily want to keep – we are stuck with their materiality – like a mobile phone case for example, which is useless after two years, but you are still stuck with the object. So I started thinking of how to make objects that aren’t permanent.

So you have a vase like this, which is made with organic binders, tree resins, shellac, beeswax, cooking flour, and dried flowers. This one (Perishable Vase III) is made with shellac, which is a natural resin excreted by beetles. I mix it with flowers, which I collect and dry and process and organise in ‘libraries’. Then I make this material and then I form it in moulds to create the vases. Because it is made from organic and natural materials the idea is that, if you don’t take care of it – for example if you put it outside – within a month it would just disappear. So there is this contrast where you create something which visually you might appreciate, but you have this back thought that it will disintegrate if you don’t take care of it. So I wanted to get people to think about objects by making something that is not permanent.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III (detail).

Perishable Vase III (detail).

There’s also the idea that it is something you don’t have to have forever.

Yes. I wanted to make an inkjet printer with this technique – looking at the idea of planned obsolescence, where a printer is designed to print 5000 pages and then it breaks down and you have to buy a new one. So if you could use this material to make a printer body you could just dump it in your garden when it is finished with and it would rot. But this material is so far away technically from what you need from the body of a printer that I decided to create a more symbolic piece, which is a vase.

And then the investigation into nature is an extension of that, thinking of the process of aging, not necessarily actually disintegrating, because of course I do actually need to sell things, but I was really interested in creating a material that evolved, so that you don’t replace it, but you want to experience the change. In the way that brass or leather age and we appreciate it for what it is.

So I started working with this PhD research graduate from Kew, and we started injecting bacteria into flowers and casting them in resin. When resin cures it reaches very high temperatures, so the bacteria needed to be able to live without oxygen and at really high temperatures. So over time the bacteria destroy the flowers within the resin, but leave the form of the flower trapped in the resin. The idea was to create a material in which light would eventually replace the flowers within, like ghosts. I had this vision of this strong black resin and then light comes in and you only see the voids after the flowers have disappeared.

Then, instead of bacteria, I started using air, because air does a very similar thing. If you allow air into the resin then the flowers shrivel and die and gradually you see this halo of light around the structures. In the Flora Table you get this silvery effect. So the flowers don’t rot and go brown, they don’t disappear, they just start becoming silvery, with these voids of light around them. So a bit like a Flemish painting, but with the aging factor.

I was also interested in going back to this idea of natural decoration, how often we are inspired by nature to create decoration, but how rarely we use nature itself to create decoration.

I started casting the flowers in big blocks of resin and slicing them up and opening them almost like a cheese, and then misplacing the slices. Each of the slices in this screen comes from four different resin blocks of flowers. Sometimes I keep track of how I cut them when I reassemble them, other times they are arranged completely randomly.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Do you fabricate all of these pieces yourself ?

I did! It was really hard work. I made these pieces for an exhibition last September, and I was late with everything. When you are coming up with a new material there is so much to learn through the process. You think you know and you keep learning. I am still learning so much from this material. I didn’t know so much about resin at the beginning, so I made these moulds and added too much catalyst, and the resin started bowing because it was shrinking too much, it was curing too quickly. So I had to do a good few runs of resin casting to get the result I wanted. Then there was so much work with cutting them and sanding and so on.

Now the process is much better. I have specialists that I go to with certain things, but I still do all the flower collection. Until recently I was also doing all the casts on my own, but because each object becomes bigger and bigger – right now I am working on a commission for a 2 metre long table – so the scale of the project requires other people, more pairs of hands. So I work with resin specialists, metal specialists. I am still very engaged with the work. With the resin casting I do all of the arrangement of the flowers. I do a few arrangements at the same time and then choose the one that I like the best. It’s a bit like painting. You choose them for their structure, but also for their colours, volumes, and then make these compositions. Once I am happy with a composition it goes in to be cast. Still during the casting there are so many things that can go differently.

I use a mix of both dried and fresh flowers. I have the size of the mould, so I know what my ‘canvas’ is, and I have all my plant libraries, which I take with me. I have times of the year when I collect a lot, and dry them and then have to keep them dry. When I need fresh flowers I get them when I need them. And then I arrange them and then there is the casting procedure.

It took me a year to get to the point where the flowers weren’t burnt or shrunk by the resin, nor for the flowers to affect the resin curing, because if you put moisture into the resin it prevents it from curing properly. It’s a very slow process and took a lot of development to get there, but I’m not going to give away my recipes!

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

What is intriguing about your work is that it is clearly very complicated to produce and yet the pieces are very simple.

There is so much technicality that goes into it, and it requires a lot of specialists. It has also been a problem with my work that producing it was really expensive at the beginning when I was producing in a self-initiated way, rather than with commission-based work. And when you are a recent graduate you find it really hard to do, which is one of the reasons, to start with, I did everything myself.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table (detail).

Flora Table (detail).

Are you primarily being commissioned to produce the furniture items at the moment ?

Yes. Actually creating the furniture work – the easiest to understand for people – has helped with the appreciation of my other work. People started getting the idea of the decaying vases much better and so I started getting commissions for these too, and now I am doing these resin pieces made in the same way as the screen, that are more like paintings. They will be framed and can also be used as wall panels. So half my work is commissioned work, and the other half is just me putting time and effort into investigating new things.

What are you working on right now ?

Right now I am working on a flower incubator. It comprises this desktop ‘machinery’ – all of the parts form a complicated system of water exchange, temperature control, hydroponic nutrition – designed to prolong the life of a cut flower to see how much longer we can possibly extend its life. So this is the opposite of the idea of constant disposable consumption. It is taking something that is already starting to decay and attempting to give it longevity.

The incubator is technically a very challenging project, and so I am having a lot of help with different specialists, so it is taking much longer than previous projects. Generally I have realised that I must take as much time as I need to develop what I want to do, rather than pushing things too quickly. It’s quite easy in this world to get trapped into working with other people’s deadlines, especially interior designers, as aesthetically the resin pieces are being seen as statement pieces for interiors. So currently I have quite a lot of enquiries from interior designers wanting to use these furniture pieces in their work.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

How do you manage that in terms of how people perceive your work ?

I am only just starting to realise that there are these differences between, say, the interiors world and the art world. When I started, for me it was all the same, I didn’t really know. Because I’m so interested in the idea and what these pieces are conceptually the selling outcome was something far from my mind. Now I am starting to distinguish how much work and commitment actually goes into creating a working piece of furniture. The resin material gives them an added value, but what I am most interested in is creating the value in the material itself – by the fact that it ages, or is not permanent.

So I am trying to shift my practice right now into this world where the pieces are appreciated for the conceptual idea. I spend quite a lot of time going out and talking to people, giving talks, to explain the work, because if you put a vase like this on a plinth and you just leave it as it is without a label people just say, ‘Yeah, it’s a vase.’, but if you give the story of why it was made and what it’s going to do in a couple of years they really perceive it differently. So the longer I am working the easier it is to make the work because people already understand it. At the beginning it was really hard to come up with the idea and have people understand it. The furniture pieces give people an easier point of entry, as people like them first for their visual aesthetics, and then when they get deeper they realise that there is this whole body of work. Of course, aesthetics are a very important part of my work. Not as the ultimate outcome, but more as the result of an investigation into aesthetics, either through making natural decoration or the aesthetics of things that decay and don’t last. I think aesthetics are incredibly important and we should never forget about them, but they are never the primary goal in my work.

So where do you see your work going ?

There are still two paths currently. One where it is more applied fine arts, and the other is me investigating this idea of impermanent things. I’m in a group show in September. I’m doing more of the vases for the show. And I’m thinking of making a decaying glasshouse where the front of it is so fine that it just disappears. That’s something that really stimulates me and gives me energy to work.

It’s also a lot about grabbing from the pool of inspiration from the past and mixing it with everything I am doing right now, like the story of flowers and the consumption aspect. One feeds the other, and then they start to feed themselves. So I guess I’ll see where that goes, but I’m really about thinking through making, so I have to be making to come up with things. It’s never just me thinking about making something and then doing it, they are all an outcome out of the past research, my palette of tools and materials, and you go with all of them until something starts getting somewhere and then you pick the ones that go somewhere and start working on developing them further. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go. I’m working on having a different creative head space where it’s all about making, so just letting myself make mistakes and experimenting.

Nowadays we are so keen to have ‘new, new, more, more’ all the time, I am trying not to get trapped in this way of thinking and take time to actually develop these approaches I have started as far as possible. My practice is also a lot about people being able to come and see the pieces, so I am really happy to now have a space where I can meet people and show them the work and explain the ideas. For it is one thing to see an image on the internet, but quite another to come and talk to me about where it’s coming from, and also the possibilities of what I can make for them.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology (detail).

Flower Entomology (detail).

Can you tell me about your relationship to nature, gardens and flowers ?

I would say that it keeps coming more and more. I started off as a blank page where I was interested in other things, but the more I work with these objects the more I appreciate nature. I have started thinking about flowers very differently. I don’t have this need to have them around me so much, as I look at them as a kind of material, and I see so much waste that it terrifies me to even think about going to buy more of them, and I don’t have a place where I can grow them as I live in central London.

Strangely plants have become a lot more intriguing to me, also because of my investigations and my talks with plant geneticists, but on just a very personal basis they have become much more, I would say, friends, where they are just this amazing source of nature you can hold in your hand. My room-mate shares the same idea and we now have more plants in our flat than I think we do cups ! It makes home so much more relaxing, especially in London.

And if you think that my past was in this 2 acre central Warsaw garden – because not only did we have the glasshouses, we also had a very particular garden, because my grandfather grew not only flowers, but all the garden plants as well. Then I lived first in the Netherlands, a small city with not all that much nature around, and now I am in London, and I am missing it a lot, which is why I have this desire to go and be in nature every now and then.

My sister and I have also just started a business together around flowers, doing artistic flower installations in Warsaw, because first of all it’s something that she is really into – it is in her DNA, she was never trained – but she just makes these amazing compositions and arrangements, and there is a big niche there for that there, as all the florists are doing the same kind of thing. No one is really thinking of flowers in terms of them being local or seasonal, or in working on the composition almost as a sculpture or painting. We’re using the same name as my grandma used to call her flower shops, which is MÁK, which means poppy seed in Polish. We only started about 4 months ago and so I am travelling to Warsaw a lot more at the moment, because we are doing this together, as she’s very young, she’s 25, so I am trying to support her, but she is the main engine and inspiration, she does all of the compositions herself. And she dries flowers for me too. She uses lots of flowers in her installations and everything that comes back to her is being dried and re-used in my work.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

What would your grandfather think ?

I’m really curious. He was a very complicated man with a very complicated way of connecting with his family so I didn’t really know him that well, but I think he would be secretly really intrigued and interested. I sometimes wonder what it would be like if I could go home and talk to him about these things and get his knowledge. My sister is always seeking knowledge about plants and my mum tries to give us as much of her knowledge as she can, but I think my grandfather would be an amazing source. Lately I have been digging through all the family archives and going through everything, because I have been trying to find a book of his – you know when you are a grower and you discover and record things for yourself ? – so I’m trying to find these transcriptions of what he was doing.

We had four or five really big glasshouses, and it was funny as it was in central Warsaw and he sold it to a development company, who took down the glasshouses, but they promised to keep the garden, because that was his condition. But they tricked him and they took it all down and built these big buildings and only kept a tiny bit of the garden. It was really sad, but we managed to rescue all these massive trees, and they were transported to my parents house on these huge trucks. They had to wait to build the house until the trees had been planted first.

Your work straddles worlds of art, craft and design. How do you classify it ?

With the craft, I think I was kind of put there more than it was a conscious decision on my part. But it’s so close to everything. It’s hard to even name it for myself. Like, when people ask me, “So, what do you do?” I seriously have problems answering this question. And it’s not because I’m trying to be so ‘artist’ about it. It’s just, how do you explain that it could be objects that don’t last, or it could be research in the Netherlands, or it could be investigating an actual decoration and making these resin pieces, or it could be ephemeral textiles ?

It is hard these days to say what it is. I don’t feel the need, or able, to classify it. It is what it is. It is other people who need it to be classified. That is fine with people who are open, and who are prepared to listen to me explain the ideas behind it, but closed people find it harder to grasp the idea of buying something that is ephemeral. It’s hard for some people to see value in something unless everyone else does. Some people at the design fairs have said that my work shouldn’t be categorised as design, but really that is just a tag for it. How people see it is how they see it.

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage