Lucy Augé is a Bath-based artist who has an passionate interest in the variety of flower and plant forms which she paints with Japanese inks on a wide range of specialist and vintage papers. Her intention is to capture the ephemeral and fleeting moment. We met last year and, after introducing her to the Garden Museum, she showed some of her new tree shadow paintings there earlier this summer. Since June, Lucy has been coming to the garden at Hillside to capture a range of the plants here on paper.

How did you come to be an artist ?

I always wanted to be an artist, even from being a child. For my tenth birthday I didn’t want a party, but wanted to go to Tate Modern, as it had just opened. I think my mum thought, ‘Oh God. Choose another career path !’. I had always been creative at school, I was never really academic, so I got funnelled down a channel into being ‘artistic’. That then followed me through to college, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist, so I did graphics, and thought I’d go into magazine design, as I had a passion for French Vogue at the time as it was so well art directed.

Then I had a really bad brain injury from a fall, and that left me very, very ill, at home. I couldn’t go back to university. I couldn’t do much, as I was having four seizures a day, and thought, ‘OK, life’s over’, but then I started gardening with my father, and that’s where I started noticing – I was going at such a slow pace, because I was so ill, I’d have to be carried down to the garden – and I started noticing things more, because I didn’t have any distractions. I didn’t have a phone for two years. Not that I was cutting myself off, I just didn’t need it. So I just started looking at nature all the time, and then I just started painting it. Repetitively. Or I was watching gardening programmes on repeat, because I wanted to know more, all the time. So, that’s where, through the illness, I got the passion for gardening and my painting.

When I finally went back to university I just felt it was very redundant for me. I went back to the graphics course as I was already a year in and because I don’t really like to give up, but I knew the tutors didn’t really like my work. They were looking for a very graphic, computer-generated style of work, and I then generally only worked in felt tip, keeping it hand drawn, but still trying to fit in with the current look that was around at the time.

So what happened after university ?

I got picked up for projects while still at university and, when I graduated, I did packaging design and worked with Hallmark, but I quickly knew I wasn’t an illustrator, as I can’t draw just anything and my passion lay with nature and studying that, rather than drawing a family of badgers eating cake. No joke, that was an actual commission.

The 500 Flowers exhibition came about after a month I spent in LA in 2015, where I had a meeting with the art director at Apple of the time, who had offered to mentor me. He set up a meeting with a carpet designer who I was supposed to do collaboration with. However, when he met me he told me that I wouldn’t be an artist unless I married someone rich, and that he would only work with me if I got someone to buy one of his rugs.

I was enraged by this and thought I was tired of waiting for someone else to launch my career for me. So I came home determined to make an impression alone, booked a rental gallery space in Bath and put on my first show on my own. The idea originally was to paint a thousand flowers, but that was near impossible in the time frame I had set myself. My brother calculated I would have to complete one every ten minutes ! So I painted five hundred, with the aim of painting every species that I came into contact with.

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

You produced all of that work and organised the exhibition yourself. What was that experience like ?

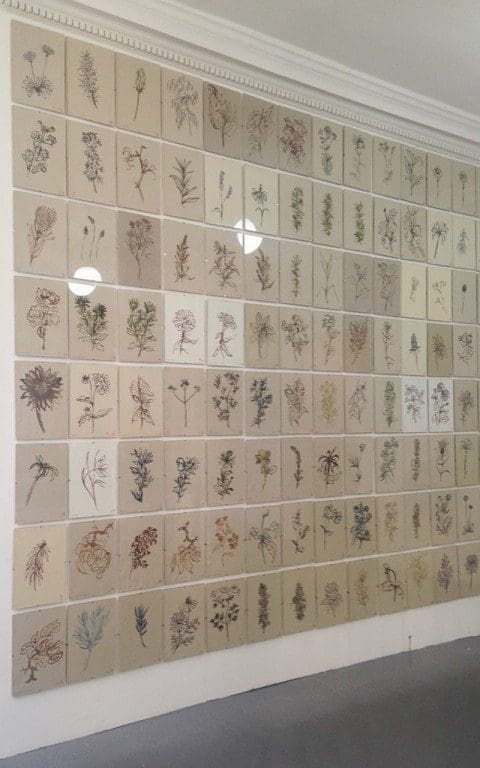

Well, I had five hundred A4, individually painted ink drawings, which I had completed in three months, and that both evolved my style and I became very confident at drawing. I also priced them at £40 each, which I think some people thought was madness, but at the same time nobody knows you, you have no reputation, and so £40 can seem like a lot for someone, but it was great because it made it affordable so that people would buy maybe nine or twelve at a time. An interior designer, Susie Atkinson, bought sixty. And so it got my name out there, because I was affordable.

The exhibition took place in Bath and I made sure I had beautiful letter-pressed invites. I invited everyone I’d ever met, contacts I’d made on Instagram or through business or who had shown an interest in my work. I invited people who I really admired for their work, which is why you and Dan got an invite. I just wanted to show people that this is what I do, this is my passion and if I fall flat on my face and no one comes and nothing sells, at least I would have known that I’d given it 100%. And then I’d have gone and got another job !

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

But it worked out in my favour. I had a queue out the door on the first night. I sold over eighty in the first couple of days. Then House & Garden emailed me to ask if they could have nine for their show, which the editor ended up buying. The assistant editor then bought another nine, and she put them up on her Instagram and I ended up selling out in five months. That then led to shows in Japan, San Francisco and elsewhere. It confirmed to me that, yes, you are on the right path, you’re doing the right thing, and the proceeds of that first exhibition went towards buying my studio. Before then I was working in a barn with no windows, no natural light, no loo, and so that exhibition was my make or break. Otherwise you can be creating, and calling yourself an artist and saying ‘This is what I do for a living.’ and yet you’ve never really put yourself out there, and so I thought, ‘baptism of fire’.

Then I started getting commissions from people to go and draw on their land, their flowers, which was really great. The best of those was for Gleneagles, which was the highlight of my career. I was flown up to Scotland, where I’d never been, and stayed at the Gleneagles, which was an amazing experience, and I went round the estate and drew all of the plants that were there at that time, and they are now hanging in the American Bar. And it was just so nice to know that people understood what you do.

Were you starting to charge a bit more for them now ?

Yes, I did raise my prices. Although I didn’t charge a lot because I wanted people to have the chance to invest in my work. I come from…my father grew up with no money, but he was always passionate about art, and just wanted someone from his background to be able to go, ‘I’m going to invest in something. Something beautiful.’ So that they can own real artwork. And I think that is a real gift to be able to do that. Especially as I had five hundred ! And the consequence now is that they have travelled all over the world. I love that there are some in Singapore, and some in Brazil and I don’t think I would have got that kind of international reach if I had not priced them so competitively. Of course, now my prices have gone up and I don’t need to produce as many. My last catalogue only had twelve paintings in.

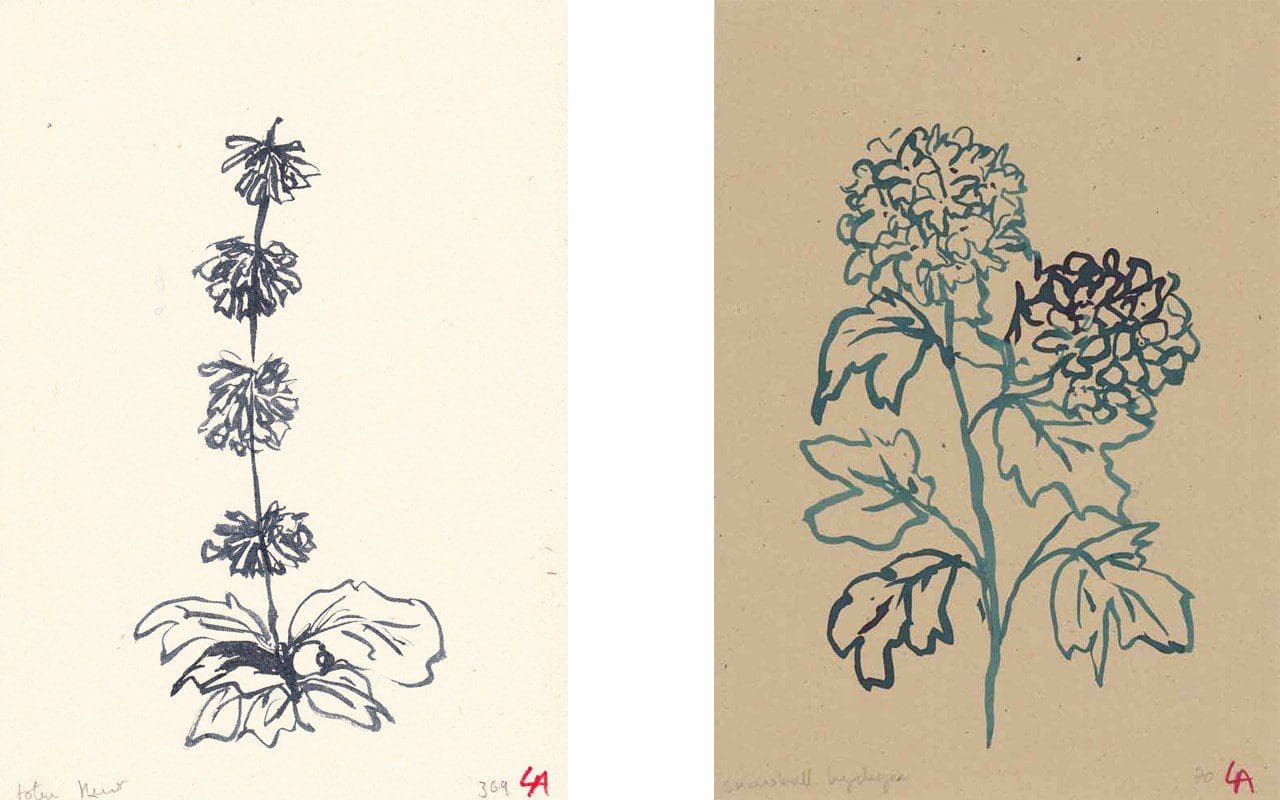

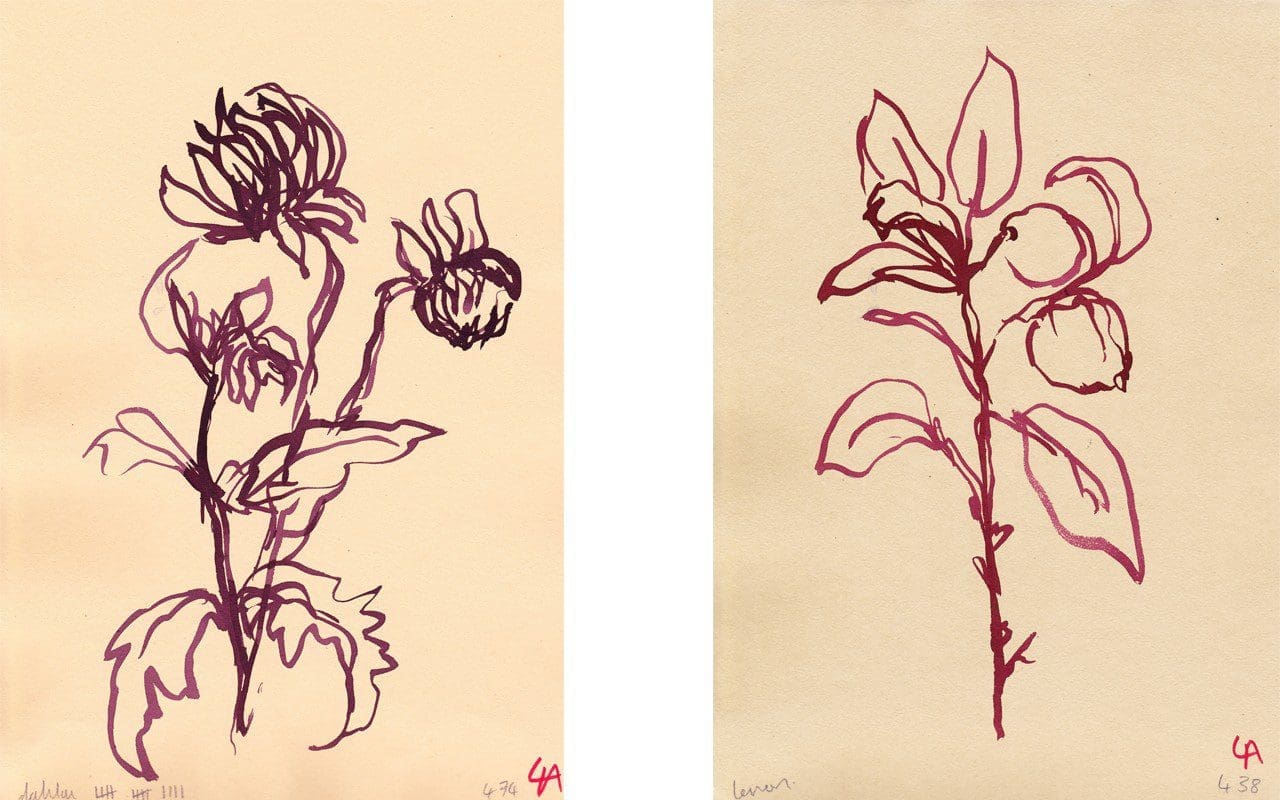

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

What was the medium you used for the 500 Flowers paintings ?

Ink. On antique paper.

I’ve seen some of your work which is very highly coloured and looks like it is done in felt tip ?

Yes, that’s right. That’s when I was still trying to be an illustrator. With those I was trying to fit in with the norm, so everything was very highly coloured for editorial. I would say that that was the only time I have ever tried to fit in. It worked for the clients to a point, but I kept being told, ‘Your work looks too much like you. There’s something to it, but it’s not commercial enough.’. So I gave it a year, doing that kind of work and I just grew out of it very quickly, because it wasn’t me.

There appears to be a strong Japanese influence in your work.

I love Japanese and Chinese art. I’ve always loved Japanese and Asian culture, so it’s always been in the background. Anything from there I could get my hands on I wanted to have a look at it, absorb it. Then I saw a show of Chinese paintings at the V & A, where I learnt that they were painting with natural pigments, so with copper and iron and earth and plants, and it just made this wonderful colour palette. So I found some Japanese inks that have that same antique colour palette, and it just felt much more me. It’s hard to put my finger on it, but it just started to fit better with the kind of images I wanted to make. And with the paper. I had never wanted to work on white. I had this antique paper, which had been in my godmother’s attic, which had the same feeling as the old Chinese papers I had seen, because they are made entirely from natural elements. So my choices were about aspiring to that antique colour palette. The other thing that struck me about that exhibition was that the artist was always invisible. The painting was never about the artist, it was about nature, landscape, weather, the seasons. It was about the everyday. And I thought, ‘Yes. Art can be like this.’ Because as I was growing up when everything was about high concept or shock, shock, shock or politics. The stranger the better. How far can you push it? And looking back at older art – one of my favourite artists is Monet – was deeply unfashionable and seen as suspect. But I love how he could just paint waterlilies and the resulting painting becomes this charged, emotional landscape.

Is that one of the reasons that you didn’t feel you could really be an artist ?

Yes, completely, and it’s one of the reasons I considered commercial art to begin with. Also I was never really encouraged at school, bar one teacher, to pursue my art. You were told that you needed to fit in. And I think as an artist you do need some kind of validation that what you are doing has value and that this is what you are supposed to be doing. And I never really got that until I put myself out there and had people say, ‘We want what you make.’ Because otherwise you can be drawing for just you – and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that – but you do have to decide that you are going to be an artist, and I made that decision after the success of that first exhibition.

I could have gone in one of two directions. I could have just put my flowers on anything and gone down the commercial route, or choose to refine the work and make it more considered. I have had a few commercial collaborations, but I have been very choosy about who I have agreed to work with or who I have approached. And I then reined it in and have now moved my work away from it, as people lost the meaning behind what I was trying to do. So they just wanted a picture of a lily as their daughter was called Lily, which is fine, but it missed the ethos of the work.

Which is ?

Seasonal observation through nature and plants. Forgotten moments. The immediacy of right now. I always found it interesting that the first pictures to sell out always are the ones of weeds. Those are the ones that people really want. I think because, as soon as you paint them, and strip everything away, you can see the beauty in them, and the fact that they are so mundane, but the painting elevates them. Honours them.

Do you know that there are 56 seasons in Japanese culture that relate to the flowering times of 56 different plants ?

No, I didn’t. How fascinating. I can so relate to that. I get quite anxious at the possibility of missing things. You know, like cow parsley. I’ll have a great idea, and then two weeks later I’ll have the time to get onto it, and all the cow parsley is gone ! So now I prep my paper in advance and cut it to the size that I want so that, when that moment presents itself, I can just say, ‘Here I come !’. That’s why when I came to your garden I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s definitely going to be, sorry to say for you, a much longer process than I had envisaged, as I now would really like to be there in different seasons.

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

What does your work mean for you personally ?

Very generally it just gives me that quiet time. You don’t have to think about anything else. Once you get into a process – it’s a bit like gardening in a sense – it gives you that same mindfulness combined with productivity, which makes me feel at peace. You’re just drawing, or gardening, and that’s all you’re thinking about. And then sometimes you’re not even thinking at all, but are completely lost in the process of activity. That’s what I really love about what I do. It’s quite addictive. It empties your mind and is very meditative. I’m a worrier. I do worry too much and it’s quite nice to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to think about anything now.’ And I’ve always been quite confident in my own work, so it feels like a very safe space when I’m creating. And once I’m happy with it and happy to put it out in the world, it’s done and I can move on.

Until then – and that’s why I have my studio away, remote. I don’t want to hear everyone else’s opinions – I don’t actually show anyone my work until it’s at a certain stage, which is almost finished. It gives me a degree of freedom and escapism. Which is why it didn’t work for me as an illustrator, because someone else is dictating what you’re going to draw, your process is held ransom by deadlines, and I’ve never been any good at being told what to do. Ever. I will question and question to understand why I should do something. Just because I’m curious, but having it be just my own work I can ask my own questions and be curious about where it’s going to go next, how am I going to paint it. And I know what I am looking for, rather than what somebody else is looking for and wants me to produce. I do find it difficult when someone says, ‘I have a tree in my garden. Can you paint it ?’, because the tree might not be the thing in their garden that I would want to paint.

What are you looking for ?

In paintings I think it’s a stillness. I really want to portray stillness, or a captured moment. So everything has to be painted from life, because it feels fake otherwise. Sometimes I do draw from photos, but you’re just not capturing that moment when that leaf on that plant might have been at an awkward angle. You might not have seen that from a photo, so that’s really interesting to explore.

The 500 Flowers were all painted from life. Firstly, all near to me and around the studio, so a lot of wildflowers, but also some bought flowers, and that’s how I got in touch with Polly from Bayntun Flowers, because I looked up ‘local cut flowers’ online and saw what she was doing and I thought, ‘Brilliant !’. She had amazing heritage varieties and luckily, when I asked her if I could visit to paint, she said, ‘Yes. Come on round!’. I was like a child in a sweet shop. The first day was so exciting I must have made about forty paintings in one go. I would normally paint about five or ten. But the garden there was just chockablock with species, lots of which I hadn’t seen before, so it was very exciting and it got me up to five hundred !

But then it was hard when the winter came. I wasn’t aware of how much I would suffer. I became quite, ‘unusual’ in the winter, because I panicked and thought, ‘What am I going to draw ? Everything’s over. My work’s not good enough.’ It was really tricky. You’ve been doing all this painting and you’ve got this absolute high from painting all these things, because there are endless possibilities and inspiration in the summer, and then my first winter I didn’t know what to do. I was really looking and trying to paint winter, but really everything is just dormant and that’s when I realised I have to know what I’m going to do when winter comes. Not hibernate.

So now in the winter I paint a lot of dried leaves and stuff like that. The first winter I was so busy, doing commissions and collaborations, that I didn’t really notice. It wasn’t until winter 2016, a year after the show, that it was total panic. A flower desert. I thought maybe it was time to do some abstract stuff, get back into illustration. It was bleak. And then there was stuff going on in my personal life, and what’s going on in my personal life does feed into the work. If I’m having a grumpy day I will most likely pick out a mopy looking plant. It’s weird. I didn’t even realise it till someone else came to my studio and said, ‘This is all a bit melancholy.’ It’s frees such an subconscious part of your brain when you’re drawing, you’re not really thinking, you’re just observing. When I saw how my moods were feeding into my work I wanted to explore that more.

The paintings that I relate to the most, like Monet’s waterlily triptych, that he painted as a reaction to the war, is so powerful and emotive, and it is ‘just’ waterlilies, and I thought I would like to try and harness that emotional connection more and be more aware of it when I am working. So the tree shadows that I have been doing most recently came about because I had drawn so many flowers – I mean I was well over a thousand different flowers by now – and I was starting to fall out of love with them, even though there were commissions paying my bills. I thought, ‘I’m on the way to making myself into a performing monkey.’. I was getting set flower lists from people, with direction on paper and ink colours and I thought, ‘I didn’t start doing this to make ready-to-go flowers.’. It wasn’t me, and felt like I was heading back into illustration territory, which I had dragged myself out of.

But then it all changed because the farmer that owned the land that the barn I was renting died and so my studio tenancy went with him. I also had some financial worries. I didn’t want to paint another flower even though it was full on summer time and I was just lying in my studio taking a nap and I could see the reflections of the trees in the glass of one of my old pictures. And I thought it was interesting. I had also been experimenting with totally abstract ink paintings, which I would cut up and make into smaller single frames. But that didn’t fit in with anything that I was doing. But I started to think about how I could bring these things together. I started trying to draw the outline of the leaves onto the frame, but that didn’t look right. Then I started drawing outdoors, which I had always done. All five hundred flowers were drawn outside. But I couldn’t get a high enough outline definition.

That’s when I realised that everything moves so quickly. I would go and get my water bottle from the studio and, by the time I got back, the shadows had moved and the picture was different. That’s when I also started noticing the weather. Timing was everything. Before that I had just been aware of when each flower I was painting bloomed – this in when the roses are here, this is when the daisies look best – but not the bigger picture. When I was drawing the flowers I was more aware of the different varieties, because when you watch gardening programmes and learn that this is what a rose looks like, this is what an angelica looks like, and then when I would go out into the fields I would think, ‘Well, that has the same leaves as a rose. That looks like an angelica.’ And so then I was learning, without any books or anything, about those wild plants. Even though I didn’t know the name I was able to match them up.

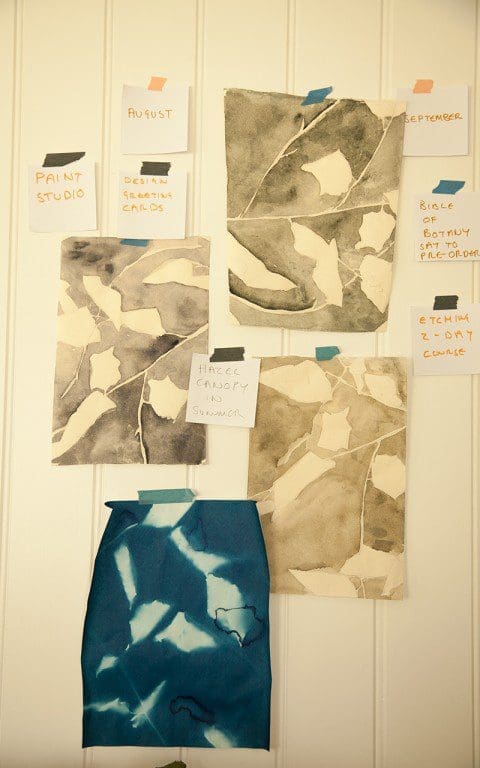

What I was finding when I started doing the tree shadows was that , even when the shadows distort, they each have a particular look. Aa certain space between the leaves. The reason I like painting hazel is they have a lot of space between the leaves. I’ve tried painting quite a few different trees, but have found what works and what doesn’t work for me, for my aesthetic. I’ve also learned that, at four o’clock, you won’t be able to get hold of me, because the phone goes off, because that is the time I’ll be painting the shadows. That’s one of the things I noticed at your place. It wasn’t four o’clock. It was later. More like five thirty, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference, because that’s when you’ve got the high definition of the shadows, like on the irises that I tried doing. And where your site is so exposed the light seemed to move so quickly. I only had a half hour window, and that was it. Whereas where I am I can start at four and not finish until seven. The angle of the image changes, but at yours I was surprised at how the time made such a big impact. It’s taken months to understand that. When is the right time to draw. What is the best weather.

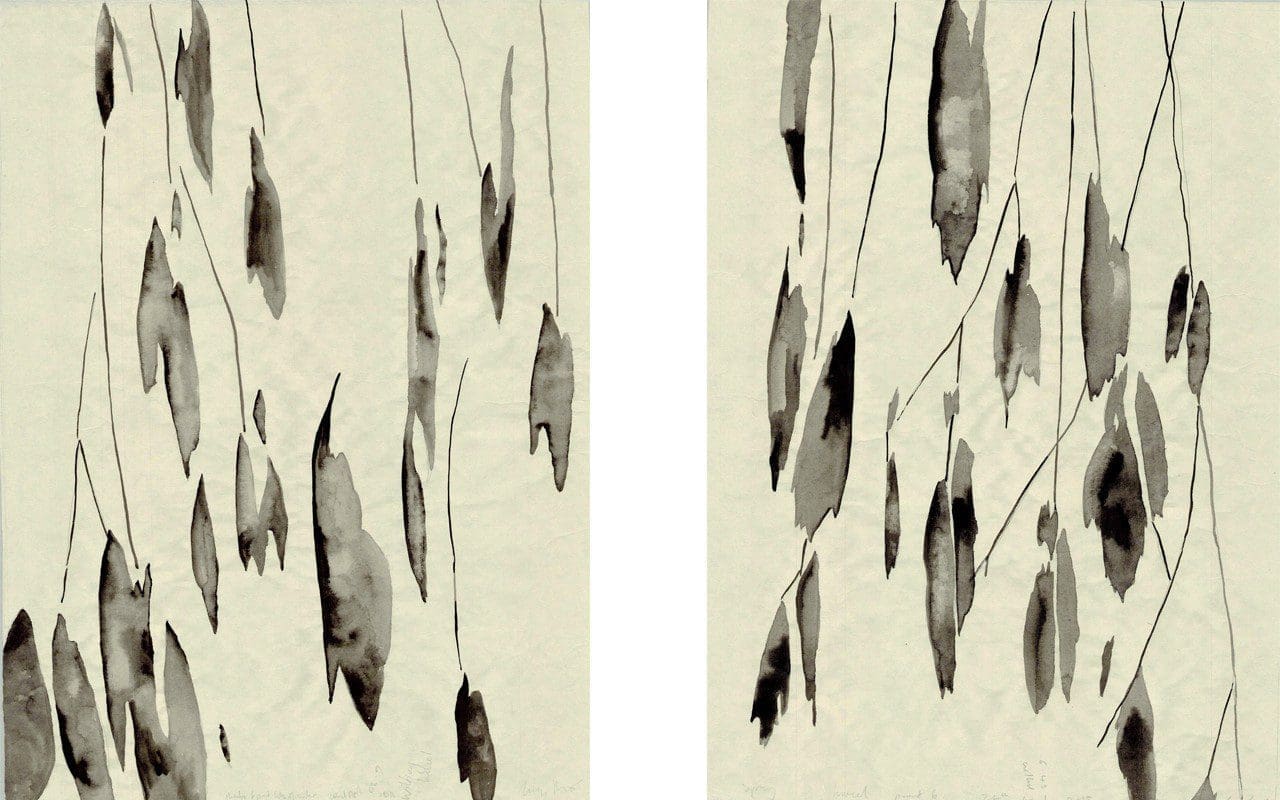

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

When did you start doing the tree shadows paintings ?

August last year. It was purely by accident. I had some leftover scroll paper and I had this birch branch and was trying to paint up into the canopy inside the studio. So I’d hung it up and then I saw that when the sun came in through the window, there it was on the ground. So I thought, ‘Oh, quick ! Get it down. Start drawing.’ I wouldn’t say that I’m drawing the outline, but more what I saw, because things move so quickly that you can’t get the exact outline, so there is a bit of interpretation involved, but I still want to be quite true to what it is, and if what it is turns out to be an awkward picture, I quite like that uncomfortableness.

So that first shadow painting, and I know this sounds cheesy, made me feel re-awoken again. I thought, ‘OK. Let’s restart.’ It was a risk, giving up on my flower paintings, which was bringing me in income, and then you think of going to your audience, who know you for your flowers, and saying, ‘I’m doing tree shadows now.’ But, the response was really, really positive. And it has been encouraging to hear people say, ‘You know I really liked your flower paintings, but I lovethe tree shadows.’

I think it’s because they feel more like art to people, whereas the flower paintings were more illustrative, the tree shadows are more abstract. But I think that doing the 500 Flowers gave me some validation, which means it is easier for people to feel comfortable with the change in direction.

When I was trying to capture a landscape through paintings of individual flowers – this is what grows here, this what I have seen and recorded – when I was in Scotland the flora there was very different, and it created en masse a very different painting. Different shapes and texture. Quite thistly, spiky plants, due to the hardier conditions up there. But not everyone got that, whereas everyone seems to get the tree shadows. I’m just really enjoying exploring it and see where it goes next.

I tried for two months earlier this year trying to capture the light coming through the canopy and it just didn’t work. Everything is a result of where I am working. My studio was too hot to work in, and so I was working under a tree – it was a walnut, which had a range of different colours in the leaves – and I was trying to capture all those variations in colour and collage them together, all in ink, in different gradients. I tried black and then green and it just wasn’t working, so I slightly felt that I was trying to – I’m always trying to come up with new work, a slightly ridiculous pressure to put on yourself, really you should just give yourself more time, so now I have gone back to doing the tree shadows. So yesterday I completed three paintings, which was a relief, because I got a bit stuck for two or three months. I do want to come back to the light through the tree canopies, because it’s been an obsession of mine for ages, since I was a kid really, when you were lying on your back on the grass looking up into the leaves with the sunlight coming through, but I can’t capture the light at the moment with the medium I’m using, so that’s why I’ve started making etchings, because the whiteness of the paper and the black ink, which becomes very matt, seems to be doing the job.

What are the challenges of your way of working ?

The etchings came about through the need to fill the winter gap. I was drawing in the winter sun, but it didn’t cast a good shadow, which I hadn’t realised, because the angle of the sun was too low. And it was a really grey winter last year, so I was waiting for the sun that never came. I did try using a lamp in the studio, but it felt wrong. It was impossible to get the light at the right angle and it felt like faking it. I am interested in capturing an ephemeral moment, not a frozen moment that doesn’t change. I have tried working from photos of shadows I’ve seen when out and about and projecting them onto the wall of the studio, and again it just didn’t feel right. I wasn’t capturing that moment that the camera had captured. And I enjoy the process of being really spontaneous. Just yesterday I had a small window to work in because the clouds were coming, and I was moving around this mock orange branch, and then the sun went, which was my fault for taking too long, which takes me back to that whole thing of not thinking and just being in the process. Every time I overthink it, it feels like I could be on that painting for weeks, and I’m not really like that as a person, so it would feel unnatural to do that.

By working with the sun I have got to know more about the passing of time, changes in daylight and seasonal changes. So I now know that autumn is coming up to peak season, because you get those amazing long shadows, which I find quite exciting, alongside the anxiety of knowing that I’m running out of time. I did do some painting in Thailand last winter. Paintings of palm trees that just looked like palm trees, and I found that quite interesting, because I didn’t know the Thai landscape, I didn’t know Thai plants, and I realised I am happier painting the familiar. Someone asked me recently why I paint hazel, and it’s simply because it’s in the hedge at the back of my studio, and it’s abundant. When I came to your place, again it was just complete overstimulation. There was so much, and I didn’t know what to choose, and your garden is very much a changing landscape. You can leave it for two weeks and come back and there will be a whole different colour palette. So when I came to your garden it just felt wrong not to paint flowers, even though in my mind I thought, ‘No more flowers. I’ve painted enough.’ It was the first time I felt like I actually wanted to paint flowers again, because I was discovering new things again, So that is something I’d like to explore more in your garden, but I need to get more used to it, as it is a whole new territory.

You told me that painting in our garden has opened up a new way of working for you. How ?

Well, the summer we’ve had this year has been very unusual. We don’t usually get weeks on end when it is just sunny every day, and I just felt like I needed to mark that. To capture the sun, and capture the flowers. So I thought, ‘How can I do that ?. So what I have noticed about your garden is that it has a lot of different shapes. All the plants have their own identity, and they all hold their own in the beds, none of them get lost. So I wanted to capture the shape of the plants, but not in ink.

With the etchings I did last winter of leaves, you just got the silhouette, and so I tried painting the silhouettes of some of your plants directly from life, and I just didn’t like the feel of them, and then the light was so amazing that that became my focus. So I started exposing the shadows onto cyanotype paper, where you are directly capturing the light on the paper. I’d first done this a few months earlier and was really interested in the process, as it produces images that are almost like abstract paintings. In some you can tell what the plant is, but in others you can’t and I like that. So the first time I tried it in your garden I was too scared to get close to the plants in the beds, and so I took the deadheaded rose cuttings off the compost heap, because I could just put them onto the paper and allow them to fall in their own way without me arranging them. I also like that element of chance. And I was also very influenced by the things you have at your place. Quite a lot of elements from Japan, a lot of natural materials and a lot of craft. And I just felt that etching, which is a craft, was a more appropriate response to the site.

So I want to create a series from your garden, but I would also now like it to be a longstanding, seasonal thing. So this summer it has, so far, been about the roses, which were such beautiful, old-fashioned looking varieties. I would like to come back at harvest time and see if I can capture that, when everything is going to seed. And rosehips. I just really want to document the seasons, as I don’t think people look at things closely enough and I think, when you’re more in tune with the seasons, you understand the world and our place in it better.

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

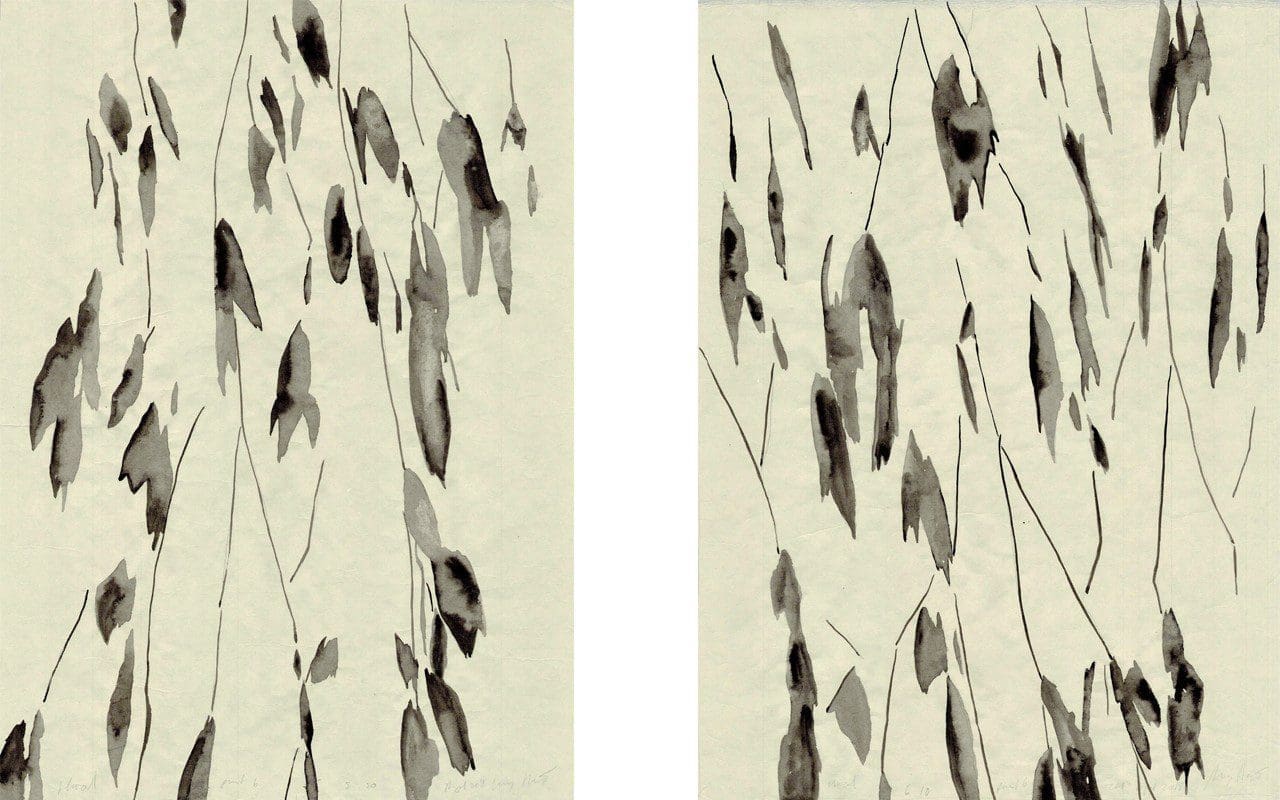

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

After last winter do you have a new approach for this coming winter ?

Yes, winter will be the time when I execute all of the etchings I am going to make from the cyanotypes taken in your garden. The process of creating etchings is quite time-consuming and complex, and it is still very new to me so I would like to spend more time getting more experience of that process. So at the moment I am just amassing lots of exposures so that I have plenty to work with later. And I am also going to explore some light and dark paintings of your garden from sketches I have made. Fingers crossed I am beginning to find a good seasonal rhythm for my work.

I’m also going to experiment more with photography, and explore the uses of light more and see where I can take it. As well as stillness I’m really interested in capturing the passing of time. For example the cyanotypes I made in your garden only needed a ten second exposure because the light is so strong there, whereas in my studio I need a fifty second exposure to create the same quality of image, but that longer exposure also captures that extended amount of time. I find that fascinating, and a route I’d like to explore. I also go to Westonbirt Arboretum in the winter, as there is always something out. Going there makes you realise how much there is to look at. There’s always something in season, or that has something in its branches to explore, and then you really are looking at winter. But I think your garden has a lot of winter interest, which I am looking forward to.

I also want to focus on the work without the pressure of a show, and just have a process for a while and see where things go, like the exhibition at the Garden Museum, who you introduced me to, and which came about very organically. I would like to be a bit more relaxed and take more time.

Do you have any burning ambitions for projects ?

I would love to be commissioned to create a stained glass window in a church. I’m not religious, but because I work so much with light, I could really see my work translating into stained glass effectively, with sun streaming through. I’d love to work with a craftsperson to do that. And I’d really love to create a design for the Chelsea Flower Show poster, which has always been something I’ve wanted to do. And I would love to do a residency in Japan.

Lucy’s work is available to buy from a catalogue on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs of Lucy and studio: Huw Morgan. All others courtesy Lucy Augé.

Published 25 August 2018

Adam Silverman is a potter living and working in Los Angeles. After initially studying and practising as an architect, in the early 1990’s he was one of the founders of cult skate wear company X-Large. Since 2002 he has been practising as a professional potter. As a keen amateur potter myself, two years ago I was inspired to write him a fan letter and was delighted to receive an email from him inviting me to visit him at his studio, which I did in October 2016. Adam generously gave me two days of his time, showing me his studio, his work and explaining his process. This March he has his first European solo exhibition in Brussels at Pierre Marie Giraud.

Adam, how did you come to work in ceramics ?

Ceramics is something that I started as a hobby when I was a teenager, around 15 or 16. Before that I did wood turning and glass blowing. Clay stuck and I continued taking classes as a hobby throughout high school and college. In college I studied architecture, but took ceramic classes whenever I had a free period. I never studied it per se just enjoyed doing it. I didn’t know anything about making glazes or firing kilns or the history, ancient nor modern. I continued making pots as my creative outlet after college and while I began my working life in Los Angeles, first as an architect and then as a partner in a clothing company.

In about 1995 I bought a small kiln and a wheel and set up my own studio in my garage at home and the hobby grew into more of a passion and then into a fantasy life change. In 2002 I attended the summer ceramics program at Alfred University in upstate New York with the intention of studying ceramics seriously for the first time. I wanted to learn about glazing, firing, history, etc. and to see what it felt like to work on ceramics full time, 8-10 hours a day, in a serious studio context, with feedback from people who weren’t friends or family. My idea was that at the end of the summer I would decide to either commit to working professionally as a studio potter, or give up the fantasy and acknowledge clay as my hobby but not my profession. It was a great summer and I returned to Los Angeles and set up a proper studio, outside of home, got a business license and went to work as a studio potter. I gave myself one year to see if I could make a living at it. That was fall 2002, so it’s been 15 years and in many ways I feel like I’m still just getting started.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

I’m interested in how you see the relationships between the seemingly unrelated disciplines of architecture, clothing design and production and ceramics.

Ceramics, clothing and architecture are all “functional arts” or at least can be. They are all made for and in many ways dependent upon the human body. They are all usually seen as “design” more than “art”. I moved from the hardest and most complicated (architecture) in terms of the amount of people and money needed to realize your work. Making clothing is very similar to making a building in terms of the process, but much faster and cheaper and less dangerous and less regulated. Ceramics I can and do make entirely alone. I have as much control over the process and results as I want. It is an amazing thing to come to work alone and be able to make what I want, when I want. This, in a way, is one of the reasons that I call myself an artist rather than a designer. I come to my studio and make what I want. I don’t have clients to service or problems to design solutions for. It’s not a service business that I am in. Anyway, you get my point I’m sure.

From 2008 to 2013 you worked as a studio director and production potter at Heath Ceramics, a tableware producer founded in the 1940’s with a distinctive Californian modernist aesthetic. What can you tell us about your time there ?

My time at Heath was great. I learned so many things, some about making ceramics and issues of production, some about design, some about running a growing business with a rapidly increasing number of employees and the associated complexities, and some about myself and what I wanted to be doing with my work and my life. It allowed me to work commercially and so not have to worry about money so much, while still giving me the freedom to both develop their homeware ranges with my aesthetic input while also producing more experimental work of my own.

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

When I first encountered your work the forms you were making were controlled and symmetrical and served as canvases for extreme textural glazes. Since then your work has become monumental, less controlled, more chaotic. How has your approach changed since you first started to pursue ceramics professionally ?

I think that I have been following a path without preconceptions of what I wanted my work to look like or be like. The evolution of the approach and the results have been very organic. The one consistent is the potter’s wheel. I love working on the wheel, that’s the foundation of my studio and, in a way, my life. The work has evolved from very clean and tight, reminiscent of modern Scandinavian ceramics, and into a much looser and freer interpretation of those same basic geometries, which are dictated, or at least implied, by the forces of the spinning wheel, circles, spheres, eggs.

I can say that there really isn’t a thought process per se behind the evolution. It is more of a physical evolution. There is a lot of improvisation on the wheel. I think as I’ve aged and become more confident as an artist, things have very naturally loosened up. In the early days I would on occasion think that I was too tight and needed to loosen up. I would intentionally try to make looser work and it always felt horrible, contrived and unnatural, and the results didn’t feel like my work. I felt that they were terrible to look at and touch.

You have developed your own glazes over many years. Can you explain how you do this ?

I am a total caveman when it comes to chemistry. I put stuff together and burn it and see what happens. I’ll find materials where I am working and use them to leave marks on the work. Usually I start by thinking about just a colour or group of colours that I want to use and then start making things and see where it goes. I use glaze recipe books, the internet, and sometimes commercially available glazes as a starting point, and then start altering them through experimenting. Also I multi-fire everything, often many times, to build up layers or to try to correct something. It’s all a bit of a mess honestly, and I can’t really repeat anything, which I like.

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

Can you tell us about your Kimbell Art Museum project in 2012, which brought you back into the orbit of some of your architectural heroes ?

This was a commission to create a body of work celebrating the 40th anniversary of the opening of the Kimbell in 1972. It is one of architect, Louis Kahn’s, finest buildings. In 2010 construction began on a new Renzo Piano designed building, while behind the original Kahn building is The Fort Worth Modern Art Museum, designed by Tadao Ando. Both architects were much influenced by Kahn.

For me as an architecture student, and then a young architect, each of these three architects were very significant, and they continue to have a bearing on my practice as a potter. So to be given this opportunity to engage with the three of them was exhilarating and terrifying. I made three large pots using only materials harvested from the site, which included items gleaned from the partial demolition of the original Kahn building, rust shed from a Richard Serra sculpture and water from the pond at the Ando building.

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

What attracted you to the Grafted project that you collaborated on with Japanese botanist Kohei Oda ?

This project was suggested and orchestrated by our mutual friend Tamotsu Yagi, who is a brilliant designer and art director. He also designed the book of the project as well as my Rizzoli book of a few years before the Grafted project.

Kohei creates ‘mutant’ cactus plants by grafting different species together. Tamotsu thought that I would be a good person to create pots for some of these plants and set us up on what was essentially an international blind date. I was reluctant to do pots for plants as I felt that I had moved past that part of my life and practice, but his work is so special and powerful that I couldn’t say no to Tamotsu. We did a few test pieces where I sent him a few pots and he sent me a few plants and the results were encouraging and exciting so we decided to do the two part show, one in Venice, California and one in Kyoto. We made a total of 100 pieces together over the course of a year. It was a pretty special project.

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

It is self-evident to say that the forms and surfaces of your pieces are organic in quality. What are your inspirations and intentions with these forms ? Your recent show at Cherry & Martin in L.A. was titled Ghosts. Can you explain why ?

In a way I prefer for the work to stand on its own without explanations of influences, intentions. I will tell you that I look a lot at painting, anything from Cy Twombly to Monet to Rothko to Philip Guston. I look a lot at architecture. And dance. But in the end none of that really matters, because I’m making pots and sculptures that must exist on their own in the world.

The title Ghosts (and, at my upcoming show at Pierre Marie Giraud, Fantômes) simply suggests the histories and lives that are inherent in the pieces. Living organisms in the clays and glazes, my hands and actions on the clay, gestures frozen. Lives stopped, but that also live on.

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Landscapes, both urban and rural, are present in your work, and there appears to be a strong Japanese influence. What can you tell us about these ?

Yes there is a lot of this stuff in the work, and all mostly unconscious or not specifically intentional, beyond using materials harvested from my surroundings, both urban and rural. I like the idea of scars and marks coming from the place where I’m working. It’s abstract and people don’t need to know and usually don’t, but to me it feels like the place is in the work and the work is of the place and somehow it resonates and means something, even if it is unspoken and invisible.

Japan is deep in my heart and DNA. When I was in architecture school I was (and still am) a huge fan of Tadao Ando and my first trip to Japan in 1989 was specifically to look at Ando buildings. I’ve been going back there my entire adult life and have so many influences from there inside me that it’s hard to tell where it starts and ends.

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Fantômes is at Pierre Marie Giraud from March 8 – April 7 2018

Interview and all other photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 February 2018

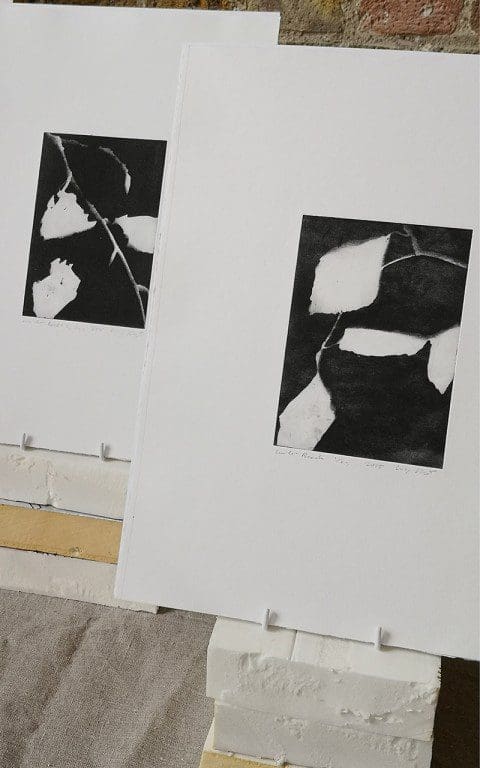

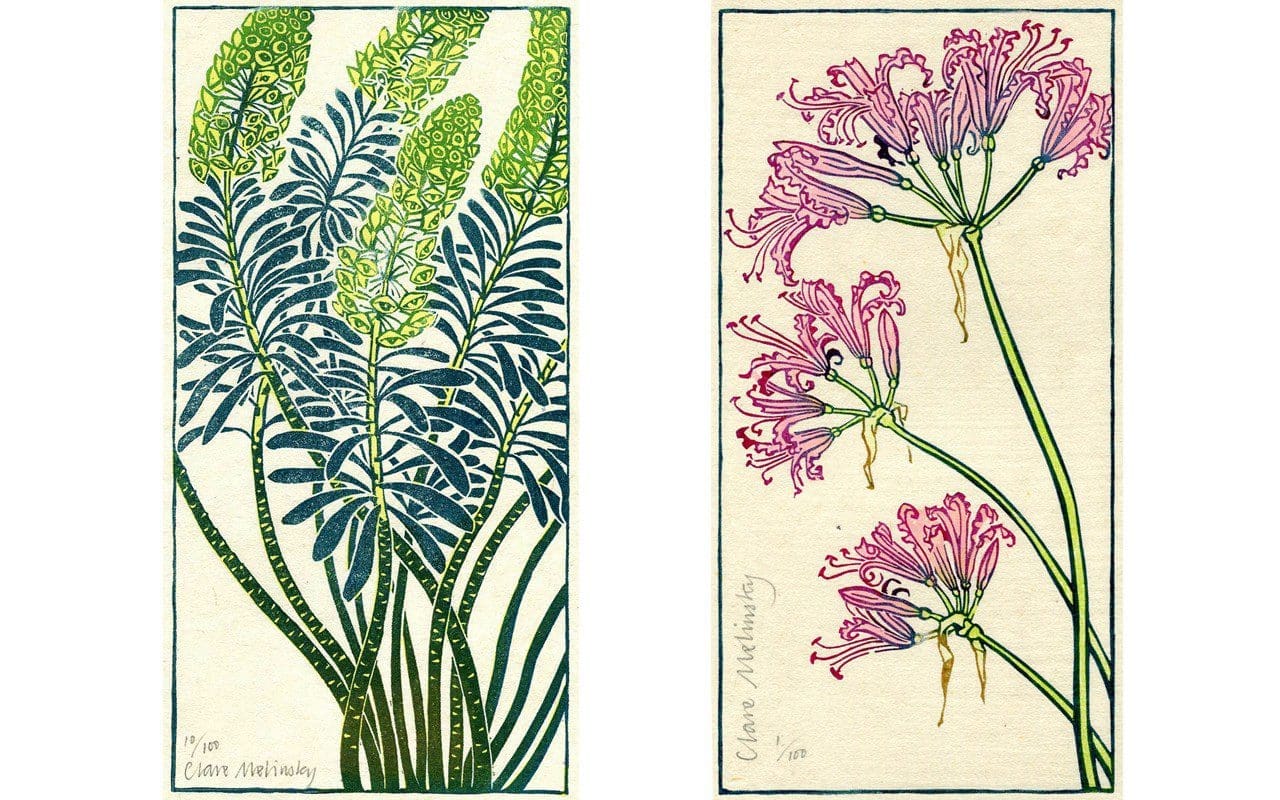

Clare Melinsky is a linocut illustrator, who created the cover and monthly chapter plant illustrations for Natural Selection, Dan’s new book which is being published by Guardian Faber on May 4. Clare was chosen for her keen eye for botanical detail, her innate understanding of plants and her talent for graphic simplicity.

You originally studied Theatre Design at Central School of Art. How did the change to linocut and illustration come about ?

In Theatre we had a seriously practical course with actual budgets for putting on productions with real actors. We stayed up all night sewing on buttons and painting scenery. It taught me about deadlines and responsibility, skills you would not normally associate with an art school education. And I also learned that the theatre world didn’t suit my temperament.

In the Foundation year at Central I had enjoyed a week of printing linocuts, and after I left college I did some linocut printing on textiles. A publisher friend, Richard Garnett at Macmillan, asked if he could use one of my motifs on a book cover: so I discovered the world of editorial illustration. At the same time Mark Reddy, a contemporary at Central, was starting out in advertising, and he, too, commissioned a linocut image from me. So I also discovered the existence of illustration in the commercial world. Both were much more financially rewarding than printing bedspreads and cushion covers. Light bulb moment: I would be an illustrator.

Illustration for Tesco wine label

Illustration for Tesco wine label

There is clearly a connection between theatre and the narrative complexity and framing of many of your illustrations. How do you go about identifying the elements required for a commission and then putting them together in a coherent whole ?

I have always enjoyed the research part of a job. As a student I spent many happy days ordering up stacks of dusty books from the card index at the V & A library, and sketching in the galleries. Now I have my own collection of reference books which I know inside out.

I like to get authentic detail of the time and place, and look for telling motifs rather than invent my own. For example the figure of Juliet on the Penguin Shakespeare cover is based on a tiny detail in an Italian fresco that I came across when looking at contemporary images, a lady leaning on a balcony: there was my Juliet. Having identified the elements, I then apply structure and colour and contrast to the specified size and shape in the short time available. Rather like garden design, I suppose.

The Holm

The Holm

You have said that your work is inspired by historic woodcuts. I can see echoes of Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and others in your work, and many of your plant portraits have a distinctly Japanese feel to them. Can you tell me about artists that have inspired you ?

I am a big fan of Bawden and Ravilious. I first came across their work at an exhibition at the Tate in 1977: The Curwen Press collection. It was a seminal moment. Before that I had studied technique by looking at Bewick’s wood engravings (1800-ish) and Joseph Crawhall’s popular woodcuts from the 1890’s.

Some years later I was given a secondhand book of mid 20th century Japanese prints collected by an American, Oliver Statler, when he was stationed in Japan after the war. These prints are known as Hanga: a revelation to me. A whole new way of looking at relief prints. More recently my daughter Jessie spent two years in Japan on a Daiwa scholarship doing part two of her architecture degree. So I was able to visit her in Tokyo, and travel during the traditional cherry blossom festival time which added a lot to my appreciation of Japanese style, and prints in particular.

Seeing the gardens in Kyoto was so exciting, in the context of their temples. Our accommodation in Kyoto was in a monastery, and we were expected to meditate in the temple for an hour before breakfast, which was mushroom broth. In the hillside moss garden, we saw the monks (or were they gardeners?) picking fallen leaves out of the moss to keep it pristine.

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

Euphorbia characias and Nerine bowdenii from the Cally Gardens Florilegium

You have said that your garden can easily distract you from your linocuts. Can you tell me about your garden and what it means to you personally and professionally ?

After graduating I still lived in London. But my partner and I spent the summers with his sister’s young family in south west Scotland on their smallholding: we decided that was the life for us too. We started with twelve boggy acres at 1000 feet (300 metres). That means high up in the hills. We were the last house, six miles up a single track road in Dumfries and Galloway, south west Scotland. Sheep, goats, a dairy cow and calves, hens, two children, geese, a pony… we were very ignorant but it was a good life and I have no regrets.

It was originally my partner who was the gardener: we had a huge and productive veg plot, organic of course, with a big input of muck from the beasts. Very good soft fruit too. It was such a good lifestyle choice, because it meant that we could afford to live off my earnings in the early years. I could never have earned enough as an illustrator to support a family, if I had stayed in London.

After thirteen years it was time to move somewhere more sensible. Not far from our first house, but a bit nearer sea level and civilisation, we now have just one cat and a garden, with a wood at the back of the house and a burn running alongside. Lots of hardy perennial flowers and a small fruit and veg plot. Whenever the sun is warm I drop what I am doing and go outside with my gardening gloves on for a couple of hours. The climate here is so wet that you absolutely have to enjoy any fine weather when it comes.

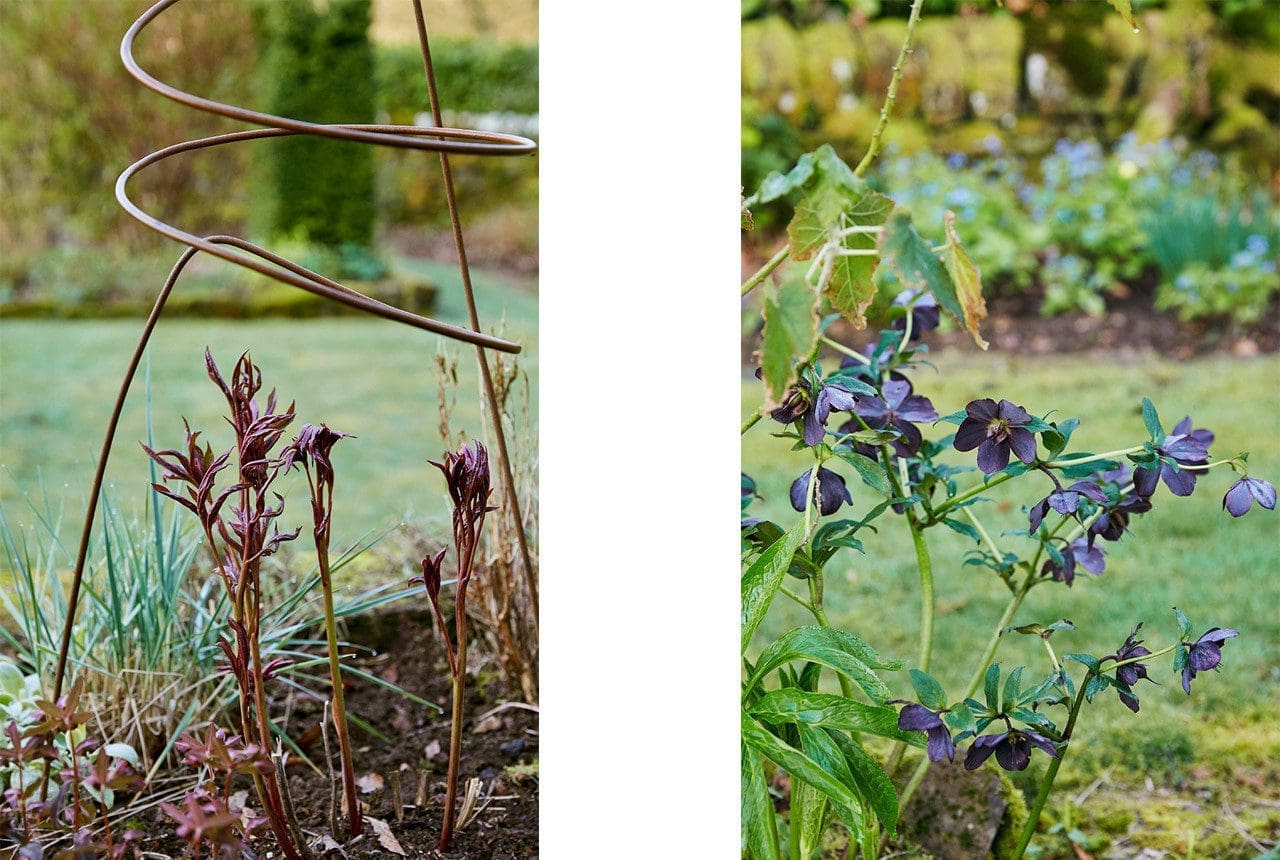

Clare’s house and garden in early April

Clare’s house and garden in early April

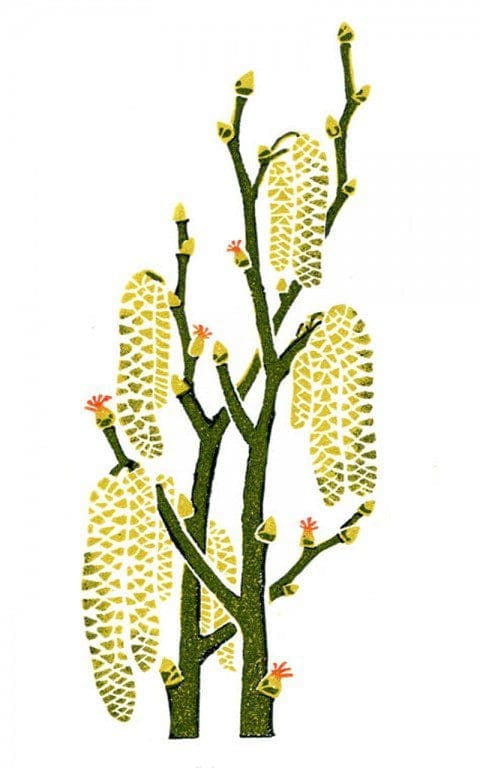

Hazel catkins

Hazel catkins

In the woods behind Clare’s house

In the woods behind Clare’s house

You work across a wide range of different media including book covers, stamps, product packaging and editorial. However, it seems that you include plants and landscape in your illustrations whenever relevant and possible. Can you tell me how your garden, landscape and plants inspire your work and influence the commissions that you accept ?

It’s what I see when I look out of the window. Most of my holidays are actually in cities by way of contrast: visiting my son Tom who lives and works in New York for example. I accept most commissions that come from my agent if I have the time: each job stimulates new ideas and creative development.

Gardening wasn’t a memorable part of childhood. I do remember individual plant experiences: a sea of lupins, as tall as us children, blue and pink and mauve, at the foot of the sand dunes on the Norfolk coast where we spent our summer holidays. A ravishing philadelphus enveloping the shed when I wheeled out my bike to cycle to school. A cataract of wisteria on an old rectory we used to visit.

My favourite toy at one time was a Britain’s Miniature Garden: little brown plastic rectangles and semicircles were the flowerbeds, dotted with holes into which you could push different clumps of coloured plastic flowers. You could buy individual flat-pack trees ready to assemble. Cardboard flagstone paths and rectangles of green flocked card with mowing-striped pattern. Little plastic rockeries and a pond and stone walls. I would save up my meagre pocket money to buy a new pack of plastic hollyhocks. Maybe that’s why I now have no hesitation in digging up a whole clump of perennials in full flower and replanting, if I decide that something is in the wrong place.

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Whenever possible Clare draws from life using the plants in her garden

Tulips

Tulips

Given the breadth of your commissions do you have a favourite subject matter ? Which appeals to you most ?

My agent comes up with very varied jobs – and I like that. I was so lucky to be invited to join the Central Illustration Agency when Brian Grimwood first started it. It is the one thing that makes it possible for me to live in the country, and still access the world of work in London. There is no continuity to the work, it is completely unpredictable what people ask for. The client has chosen me because they like my linocut style. So it is often more of the same. Since I finished your book I have done images for food packaging for Waitrose, a folk tale illustration for Britain magazine, and some labels for a local cider maker. Sometimes it all goes quiet and I don’t get a job for six months.

Primula auricula

Primula auricula

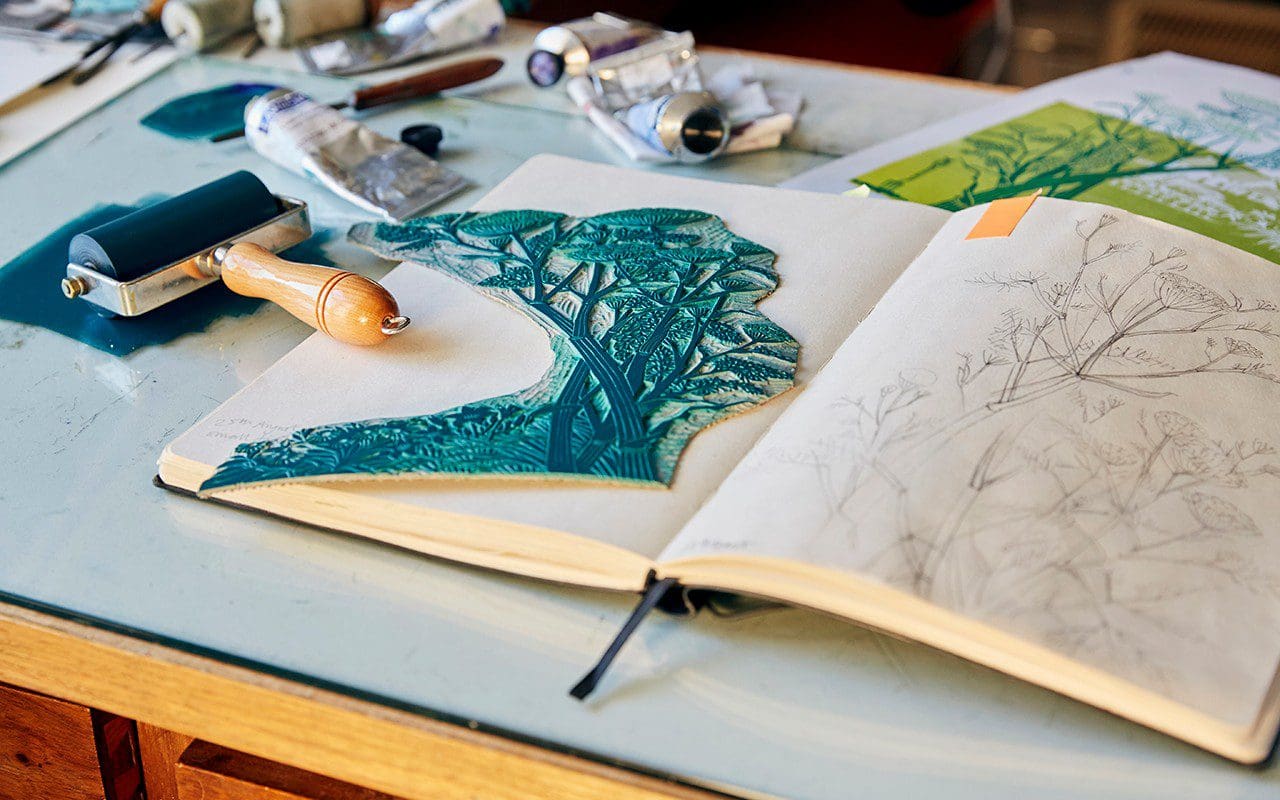

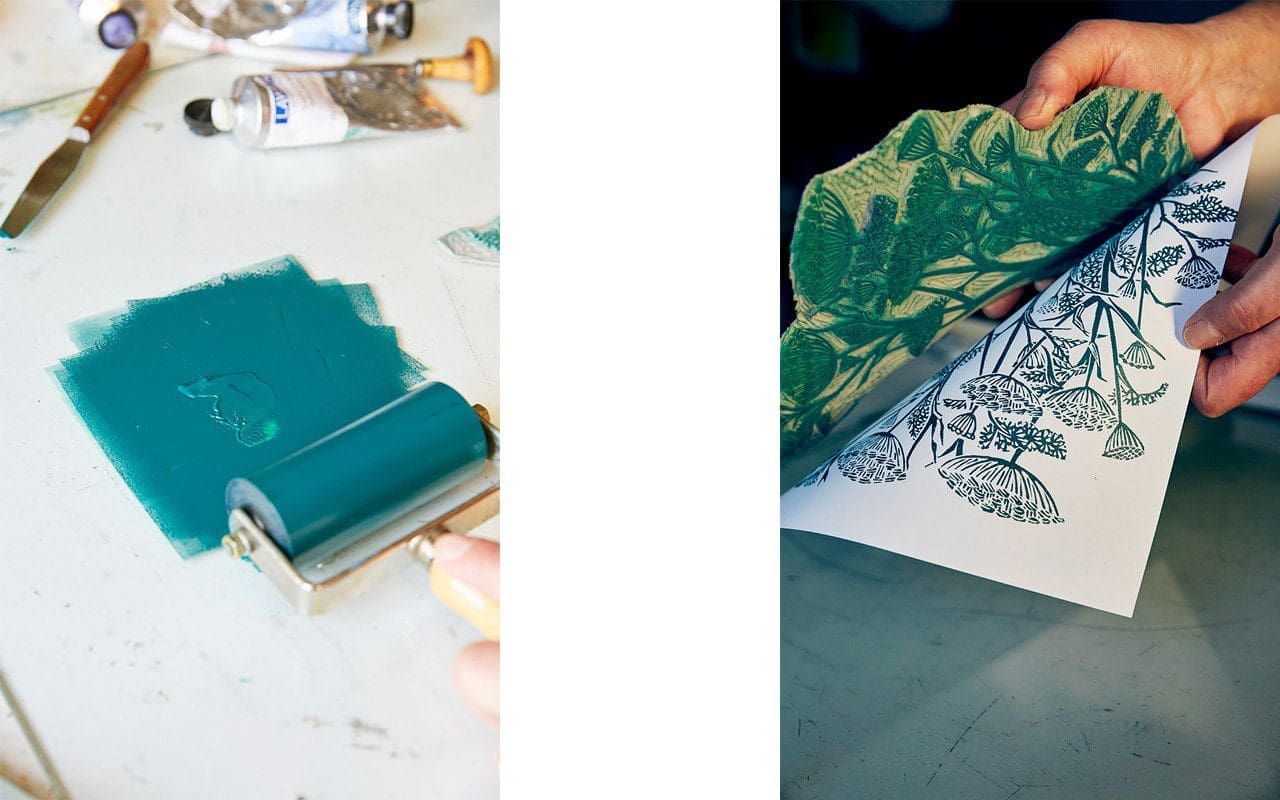

Can you explain your design process from sketch to finished print ?

I do a rough drawing to show the client. Once that is approved, I transfer the image onto a piece of linoleum. I buy my lino from a flooring supplier by the metre. Cutting a design into a piece of lino calls for simplification and clarity. I am obliged to be selective. If in doubt, leave it out.

As it is a print, everything has to be done as a mirror image. I cut into the lino with a set of five small v-shaped and u-shaped gauges. I have to decide whether to show the veins on a leaf, or the outline of a leaf, or I can just depict the solid shape of the leaf. Less is more. The areas of lino that I cut away won’t print. When I roll the ink onto the finished block, the remaining lino will pick up the ink. Then I make a print using my big press.

I can print in black and white, but mostly my work is brightly coloured as it will be used on a book jacket or for packaging. I can add more than one colour onto each block using small rollers. Where the colours merge makes an interesting blend. Then when I print a second block over the first print, more subtle and interesting and unexpected things happen. The inks can be mixed to be quite transparent, or quite opaque. I use linseed oil-based relief printing inks from Lawrence. I was introduced to Lawrence’s at art school, when they were at Bleeding Heart Yard in London. I am still using the same tools that I bought there, though the smallest v-tool has been retired and replaced: it became rather short after years of sharpening.

Making the drawn line into a cut line transforms the quality of the line itself. I am still always surprised by what I have created when I see the first print.

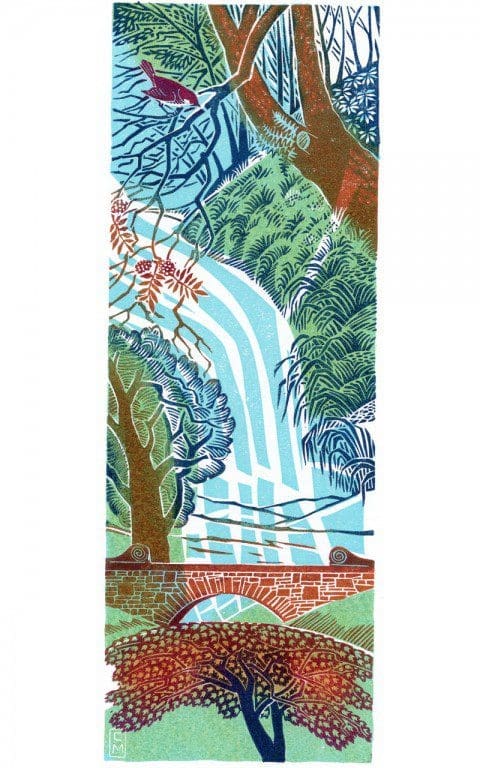

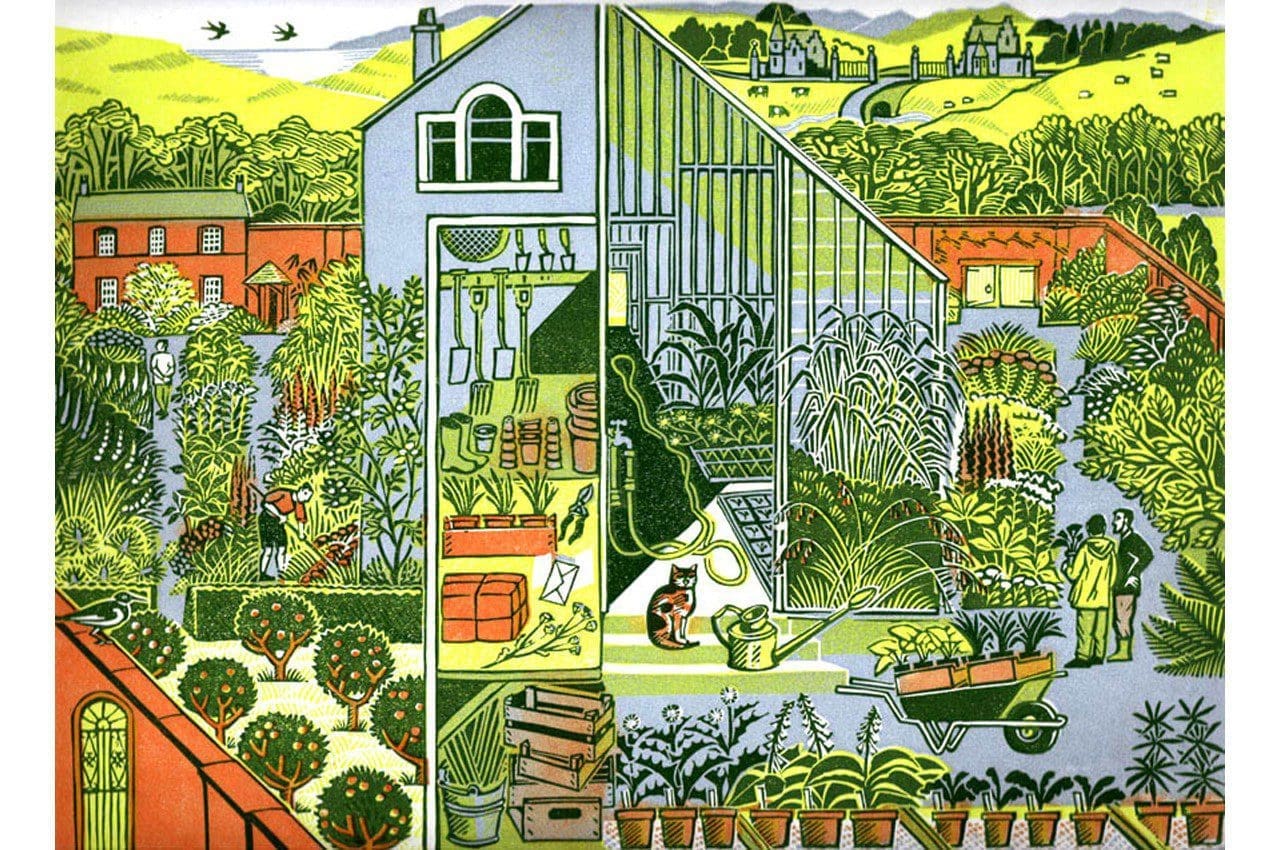

How did you approach the commissions for Natural Selection ? The cover image features a house which looks very like Dan’s house in Somerset. Did you research images of it, or is it a happy accident that it looks so similar ?

I was so pleased to get this commission, I knew right away that I would love to do the book. If the house on the cover looks like Dan’s, then that is a happy accident: that’s my house more or less. Mine actually has dormer windows, but I thought Dan’s house would look more English with ordinary smallish windows.

I first came across Dan’s name in the early editions of Gardens Illustrated when it was something new and special. And have followed his career haphazardly, since I don’t have a television, in occasional gardening magazines. Dan decided to have one plant portrait for each month. We had different ideas about which plant, but I was happy to go along with his choices. The only problem was that by then it was October, so I couldn’t draw all the plants from life which would have been preferable. But mostly I had drawings that I could refer to. I happily use photos for reference, but I still think the best work is done from life if possible.

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural Selection

The hand-printed cover artwork for Natural SelectionWhat are the greatest challenges in your work ? Can you tell me about the brief for the murals at Beatson Hospital in Glasgow ? How did you visualise your work for such a large piece and how did you scale up your linocuts for the site ?

I knew my linocuts would look good reproduced at a larger size. It enhances the irregular quality of the line, the handmade look. It was exciting to see the A4 size images enlarged to two metres high, extending over four thirty metre corridors. Each corridor was named after a Scottish island as a theme, and I rearranged my selection of details of the countryside to create a harmonious and varied flow of landscape and wildlife for patients and staff to enjoy as they passed by time after time.

The Beatson is the hospital for treating cancer patients in Glasgow, and the Macmillan Fund provided money for an art consultant, Jane Kelly, to enhance the whole interior with colour and style and fittings, with the Scottish west coast as the overall theme. Very worthwhile and successful.

Each job is a challenge. The deadlines are tight. Understanding what the client has in their head is a challenge: they often know what they want, it is my job to find out what that is and turn a concept into an artwork.

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

Part of the Beatson Hospital Mural

You have produced a number of illustrations for Cally Gardens over the years. It was a shock to hear of Michael Wickenden’s recent death in Myanmar while on a plant hunting expedition. Can you tell us about your relationship with Michael and the nursery ?

Michael’s fantastic nursery is an hour’s drive along the coast from here. He had bought a derelict walled garden thirty years ago and filled it with his vast collection of plants over the years. I was there doing a drawing for the Garden History Society. On seeing the final product, Michael asked if I would do a design for him to use on his Cally Gardens mail order brochure. We became firm friends, and the brochure has been published every year with my cover design. Until this year.

It is so sad that he is no longer with us, but I firmly believe he would be delighted to have died on top of a remote mountain on a great adventure. He knew that he was taking a big risk going to these remote places, and loved the expeditions, traveling with native guides under extreme conditions. As I tidy up my flowerbeds after the winter, I can recognise each plant that came from Cally, and I am reminded of Michael each time.

He was very outspoken and didn’t mind causing offence, objecting at every opportunity to the Plant Breeders Rights nonsense. I also learned from his example that my flowerbeds should be rigorously tidy in March. His garden looked like a jungle by the end of the summer, but in March everything (well no, maybe not everything, it’s a huge area) was cut back and isolated into its own distinct space. We all hope that some gardener with vision will grasp the nettle and keep the place going.

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

Illustration for the cover of the Cally Gardens catalogue

What are you working on at the moment ? What would be a dream commission ?

Just now I am designing a publicity image for an exhibition for the Royal College of General Practitioners. Then I have to print up more work for my local Open Studios event 27th-29th May 2017. I also teach linocut workshops, including residential courses at Higham Hall in the Lake District three times a year which I enjoy.

A dream commission: Natural Selection in an Italian palazzo with a cook and a housekeeper and a gardener. In the sun, with a swimming pool. With a whole year to do the work, so I could draw each plant from life. My partner and children and friends, and my agent, would come to visit at intervals… Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photography: Emli Bendixen / All illustrations © Clare Melinsky

Cleo Mussi is a mosaic artist who worked with Dan on one of his first Chelsea Flower Show gardens in 1993. Her work is concerned with the influence and importance of nature, man’s place in the ecosystem and the effect we have on it through such practices as intensive agriculture and genetic modification. She brings a critical, politicised and humorous eye to an old folk art tradition.

You originally studied textiles at Goldsmiths. Can you tell me how you arrived at working with mosaic and the connections between these different materials ?

In the late 1980’s I was creating wall pieces using a number of textile processes, printing, weaving and patching together found (essentially affordable) fabrics. Charity shops, car boots and skips were an Aladdins’ cave. I was also studying ceramics at night school. When I left college I began to explore mosaic as a technique and taught myself through trial and error. My work is created from second hand table-ware and ornaments patched and pieced together as with the textile tradition. Originally I wanted to make durable artworks that could be created for both interior and exterior spaces though, due to our climate, very low fired ceramic is not suitable for outside, so all my pieces are interior now.

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

Cleo’s studio, works in progress and her meticulously organised drawers of raw materials

You worked with Dan on one of his early Chelsea Flower Show gardens. How has the market for your work changed since then ?

My work has evolved very slowly over the years. When I left college, my contemporaries – the YBA’s from Goldsmiths – were having their first Frieze show and I was making hundreds of tiles and glass mounted works, some of which I exhibited in an architect’s office on Brick Lane and also in an empty shop in Hoxton. I had a studio on the Old Kent Road and then later at the South Bank.

In 1992 I was lucky to be accepted for a show at the Royal Festival Hall called ‘Salvaged’ and was then offered a subsidised studio. It was a fantastic space full of makers working in a variety of disciplines inspiring and helping each other. I think it may have been the ‘Salvaged’ exhibition and subsequent press coverage that introduced Dan to my work. It was Dan’s second Chelsea garden, very vibrant and rich with intense colour, and I think the mosaic complemented the planting. It was a real education seeing him create and plan a show garden and being on site during the event. I still have a number of plants that he gave me when he dismantled the garden and they remind me of that time. Plants, like china, hold memories and connect to people and events.

Since then my work has evolved in that my projects are more ambitious and my work is more refined in the making and the conception of the ideas. I create large installations of up to 90 mosaics for new touring shows on grand themes that I am passionate about. Interestingly my clients are still the same sort of people, individuals and establishments that love the work for what it is, for what it is made from and the inherent properties in the china, for the memories they revive, and for the stories that I tell.

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

The water feature in Dan’s 1993 Chelsea Flower Show garden designed and made by Cleo

Nature is clearly a very important theme in your work, and I know that you are a keen gardener. How do nature, gardens and plants inspire your work ?

I had my own small patch as a child and gathered euphorbia milk and strawberries for my dolls. At an early age my mother taught me about plants; that rue can cause blisters due to photo-allergy and that monkshood is deadly. My mother loved and feared plants. My parents’ oldest friend was Roger Phillips the photographer, ‘Wild Food’ author and mushroom hunter, so this was all part of my childhood. And that Darwin ruled, OK !

My father was an engineer, which is why I love structures and cause and effect and my mother was a human biology teacher, Naturopath and keen gardener. Plants were to be respected, but entice us to take advantage of them to keep the species alive and they in turn take advantage of man. I collect plants like old china, gathered at every opportunity, divided, seeds collected, cuttings taken for my own garden and lovely meals made from produce either grown or from the hedgerow.

Cleo in her garden

Cleo in her garden

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Large Collector’s Baskets with Bees, 2014. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi. Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bouquet, 2005. Photograph courtesy Cleo Mussi.

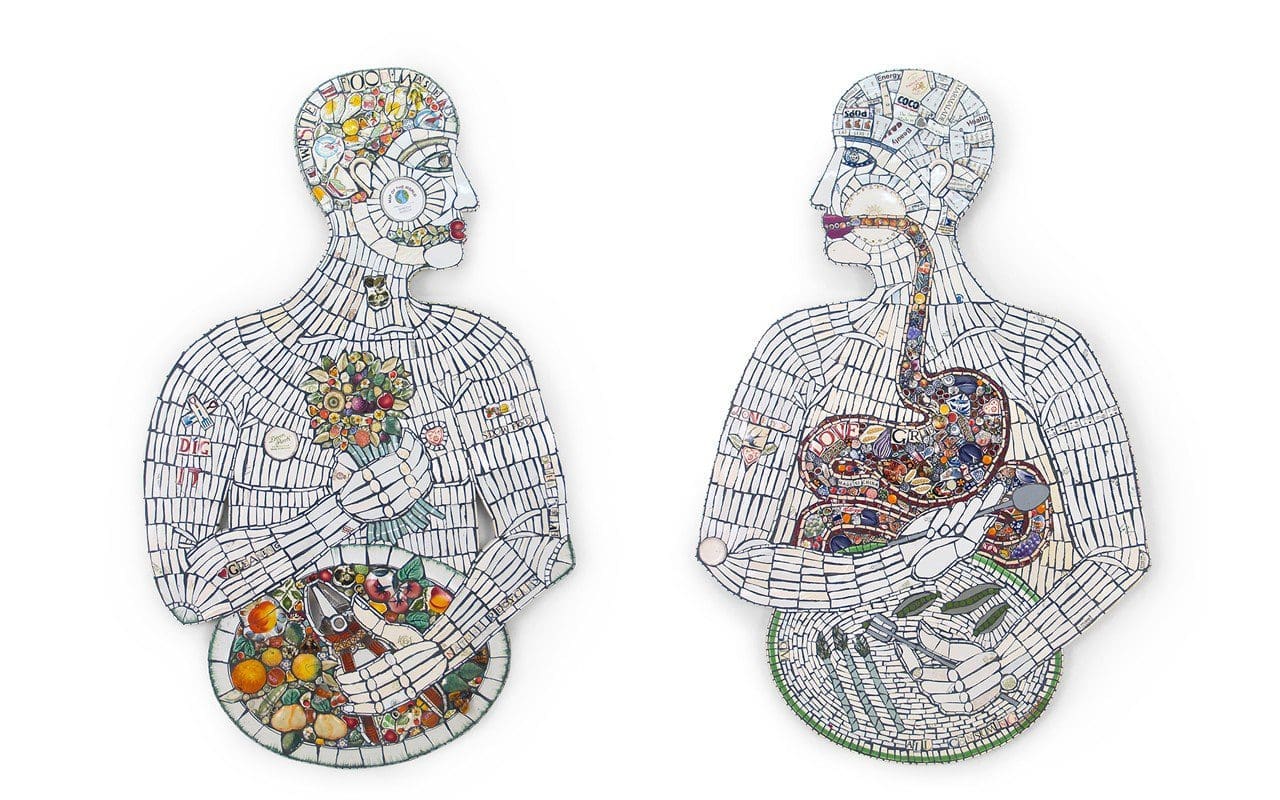

Can you tell me about your recent conceptual shows ‘Pharma’s Market’ and ‘All Consuming’, the themes you explored through them both and why they are important to you ?

These exhibitions connected ideas about food, agriculture and animal husbandry with modern developments in stem cell research, genetic modification and alternative energy. I am intrigued by evolution from the microbial soup in sea vents to archaea, bacteria, viruses, plants and animals; the physical details, the names and the stories and connections on the cellular level. These exhibitions explored the history, the characters, plant hunters, collectors and science. I observe man’s destruction and consumption of natural resources and the impact on our environment, whilst being inspired at the creativity and imagination to solve problems. For example, most recently the discovery of mycelium that neutralise toxins in toxic waste or that bind clean plant waste to form biodegradable packaging, or fungi that help in cancer research. More recently I have become interested in cyborgs and biophysics as well as in the Human Brain Project, the Human Genome Project and, of course, the microbiome; the little gardens in our own bodies yet to be discovered.

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Nature Recycles Everything (left) and All Consuming (right), 2014

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Monoculture Perfection, 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

How has your work changed and developed since you first started ?

When I first started making mosaics, my work was quite simple: tiles, tables, abstract wall panels, naïve faces and fountains for conservatories and gardens, I contributed to many gardening and craft books. Currently my work is generally exhibition focused with a number of commissions alongside mainly for private individuals, but also for arts centres and hospitals and businesses. The pieces are figurative and tell a story. I often have dark tales to tell, but with twists of humour, layers and details hidden beneath the surfaces.

You made a research trip to Japan a few years ago. What did this bring to your work ?

As a family we went to Japan for 4 weeks as my husband Matthew Harris (also an artist) and I were due to create a joint touring show called 50/50 starting at The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath. It was a fantastic experience, and refreshing to develop new work purely from visual information. We were inspired by very different things, but both of our work is constructed from fragments. We incorporated our research and inspirations. In the final exhibition, which unified the work, we had cabinets of sketchbooks, objects and photographs. We visited many of the moss gardens and temples as well as contemporary art and cultural sights. It was from Japan that I developed my interest in Kawaii and Japanese spirit creatures which include such unusual characters as fire-breathing chicken monsters, a red hand dangling from a tree, the spirit who licks the untidy bathroom and other inanimate objects that come to life.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Harajuku Fruit Branch with Blossom and Chrysanths, 2011.

Outlaws – Wanted Dead or Alive, 2016. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Your work clearly engages with the history of mosaic craft as a means of storytelling. It also appears to increasingly be concerned with political or social themes.

I think of myself as a modern day folk artist. In the traditional sense of Folk Art my work reflects the world that we live in whilst connecting to bygone days. The mosaic technique is simple, but the content has depth. The work can be read on many levels and I often touch on word play and double meaning. The work on one level is purely decorative celebrating colour form and pattern and, alternatively, on another level has a political content.

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Systema Labels: Bees, 2016

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bombus Spiritus Johnson Brothers, 2015. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

What are you working on at the moment ?

I am creating a new touring show which I hope to take to London as well as nationwide. The ideas are in their infancy, but I am looking at how weeds have evolved and the relationship between them and man’s migration and establishment of agricultural settlements. I am interested in the symbiotic relationship that we have with plants and the delicate balance of what we ingest as cure or poison and what we cultivate as food or weed.

I love the colloquial names ‘Bunny Up The Wall’ (Ivy-leaved toadflax), ‘Bomb Weed’ (Rosebay willow herb), ‘Jack Jump About’ (Ground elder), ‘Kiss Me Over The Garden Gate’ (Pansy), ‘Summer Farewell’ (Ragwort) and all the Devils; claws, blanket, tongue, fingers, etc. Many of these weeds were migrants, and yet they define our landscape. I am intrigued by this language that comes from the people who worked the land, often describing the plants and ‘weeds’ in terms of endearment or loathing from their working days; knowledge passed down by example and word of mouth.

What do you find to be the challenges and differences between self-generated work and commissions ?

Time is always the master, and the work is very time-hungry to physically create. I constantly alternate between making work that people would like to live with and thus support the creation of the more challenging pieces. I alternate between smaller works, which I make in series, and the large one-off exhibition pieces that can take weeks to make. I love to take on new large commissions as these often bring new ideas into the mix that I may otherwise not discover. Recent joys were a Donkey with Baskets for Vale Community Hospital in Dursley, a giant magic cat inspired by Edward Bawden, a piece about education called ‘Ode To Ed’ at Prema Arts in Uley and a Solar Panel Installation Worker for Primrose Solar in London. Pretty diverse.

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Corn Cob with Dark Kernel (left) and Asparagus (right), 2014

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Carrots (left) and Broccoli with Dots (right), 2014. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Can you tell me about your role in The Walled Garden at The Museum in the Park in Stroud ?

‘Patron of The Walled Garden’. I am rather pleased with my new title. I have been asked to create a planting scheme on a shoe-string budget for this special space. The garden is about a third of an acre and is managed by teams of volunteers. Essentially the back garden is open at The Museum in The Park. It was untouched for over 50 years and it has now been given a new life as a place for education, contemplation and creativity for the community. Since 2008 numerous volunteers have contributed time and knowledge to this space. Starting with secret artist donations to raise funds and teams of people excavating and clearing, sifting, weeding planting and now watering. The hard landscaping and education space was commissioned and completed last year and now it’s time to put the icing on the cake. So, with just a few hundred pounds, we have purchased a handful of plants and the rest, as with my own garden, have been gleaned and propagated, split and gifted to create a new garden in about 14 sections. Dan kindly donated a huge and varied selection of irises, which have been combined with a collection from Mr. Gary Middleton, so we will have quite a show this May.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Kyushu Tea Vases, 2011.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Bento Box, 2011. Photographs courtesy Cleo Mussi.

Starting from scratch enables us to make bold decisions; not to use blanket herbicides, our weeds are ‘hand picked’. We have introduced English bluebells under the mixed hedges and a wild seed mix and snakeshead fritillaries in the newly planted orchard, rather than lawn grass. The beds are divided into sections and aptly named ‘Bobbly Border’, ‘Bonkers Border’, ‘The Hot Bed’, the ‘Red Hot Bed’ , ‘The Purple Complementary’ and the more gentle ‘White Border’ and ‘Fernery’. Being a walled garden it’s a very hot space with very little shade, so this has been both exciting and challenging and it will also be interesting to see what survives through the winter. So the garden will evolve. This is our first season and the garden has established incredibly well. I think it has a secret underground water source. We are open to the public and anyone is welcome to visit. Coming up now are species snowdrops, ‘Wasp’ being my favorite, an auricula theatre, a tulip bed for cutting (inspired by Dan) and then later -fingers crossed – a bonkers display of zinnias for bedding, as well as all the other aspects of the garden in each season.

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo holding a recently completed Tussie Mussie, 2016

Cleo’s work can be seen in these upcoming exhibitions;

March 18th – May 7th

‘Pour Me’

The Devon Guild of Craftsmen

Riverside Mill

Bovey Tracey

Devon

TQ13 9AF

Mid-May for 6 weeks during the Hay Literature Festival

‘All Consuming’

Brook Street Pottery

Hay-on-Wye

Hereford

HR3 5BQ

May 6th & 7th and 13th & 14th

Select Trail

Open Studios

Frogmarsh Mill

South Woodchester

Stroud

GL6 7RA

Instagram: cleomussimosaics

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage