The leaves are nearly all down in the wood, winter light fallen to the floor for the first time in half a year. A new horizon meets us as we look out from the house. Not onto the weight of the poplars and their understory, but through to the slopes beyond. The tracery of branches clearly identifying one tree’s character from the next, the tilt of trunks, the hug of shining ivy.

Everywhere the scale change is remarkable and we find ourselves drawn out into the landscape with refreshed curiosity. Much of this is simply to do with a season’s growth dropping back into dormancy. Under the elderly field maple in the clearing by the stream a coppery skirt lies in a circle where the leaves fell in the still air there. Looking up into the newly naked branches a world of lichens and moss – grey, silver and green – has made them home. The nettles that just a month ago were lush and keeping us from the stream have half their volume. With continued frosts in the hollow they will be nothing but brittle stem in a month and we will be free to walk its length once again.

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

The stream is audible from up by the house in all but the driest weeks, but now it is charged with winter rain and the noise pulls us down to look. You can easily lose an hour or more if you start to explore the mud and shingle banks, as the stream landscape is always changing. A log from higher up, driven down by storm water, causing damming and silting up, contrasts with the constancy of a favourite boulder, marooned in a pool of its own influence, a home to moss and liverworts.

The moss-covered boulder

The moss-covered boulder

Although the stream is small and at times hidden, it is a favourite part of the property. Soon after moving here at about this time of year we started bank clearance and every year we have done a little more. A barbed wire fence that ran its length to keep the animals in the fields is all but removed now, the rusty coils disentangled and pulled free of the undergrowth and the rotten fence posts removed. As a reminder a number of oak posts that outlived the softwood ones were left to mark the old fence-line. They are now cloaked in emerald moss and, when working in the hollows, are perches for watchful robins.

In places the stream disappeared into a thicket of bramble to emerge again lower down without revealing its journey. The child in me had to know what lay within and the mounds of bramble that bridged the banks were cleared to reveal, in one case, a lovely bend and, in another, a pretty fall and outlook where I have planted a small Katsura grove. I have plans to make a shelter there for watching the water when the trees are grown up, but for now it is simply enough to have the plan in mind as a potential project.

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

Slowly, and in tandem with the clearances, I have started to plant the banks on our side where the farmer had taken the grazing right to the very edges. Although we do not want to lose the stream behind trees for its entire length, it is good to balance the volume of our neighbour’s wood on the other side and, in places, to protect the banks. The new trees, just sapling whips at the moment, have been planted so that we can weave in and out of their trunks on the walk up or down the stream and with or against the flow.

Tree planting is one of my favourite winter tasks. The young whips are ordered in the autumn and are with us from the nursery not long after the leaves are down when the lifting season starts. If I can I like to get them all in before the end of the year so that their feeding roots are up and running by the spring when top growth resumes.

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder (Alnus glutinosa), a riverine species that likes to dip its feet into the water, is one of the best for stablilising the banks. The roots, which produce their own nitrogen and charge young trees with vigour, are dense and mat together to form a secure edge where the banks are crumbling from having no more than pasture to hold them together. The deer that have a run in the woods have loved the young growth so, after a year of grazing which left them depleted, I have resorted to using more than spiral guards to protect them. The cylindrical guards are not pretty to look at, but give the saplings long enough to jump up above the grazing line and gain their independence.

Alder catkins

Alder catkins

Alder leaf buds

Alder leaf buds

In the deeper shade of the overhanging wood, and where the alders have proven to be less successful, I have used our native hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), encouraged by a mature specimen that, together with an oak, teeters on the water’s edge. It too has a dense root system and loves the heavy clay soil on the banks that lead to the water. Both the Carpinus and the Alnus have good catkins, which are in evidence already on the alders. Purple-brown and already tightly clustered, with hazel they are the first to let you know that things are already on the move in early winter. The alder buds are also violet and your eye is pleased for the colour which is intense in the mutedness of December. The keys of the mature hornbeam are still hanging in there and glow russet in the slanting sun that makes its way down the wooded slopes.

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Keys on the mature hornbeam

Keys on the mature hornbeam

After winter rains the stream rushes in a torrent that would sweep you away if you tried to wade across it, so this winter the stream work will turn to the bridges. Firstly to clear the remains of a stately oak that fell under the weight of its June foliage and then on to repair the clapper bridge that we made a couple of years ago and which was washed away in the heavy rains just recently. For now the fallen poplars, with their perilously mossy trunks, provide the link to the wood from which they fell. One came down the first summer we were here, and another two years later. Now the fallen oak has changed the stream once again and with it our winter diversions.

The fallen oak

The fallen oak

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 January 2017

I have just returned from my annual visit to the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been making the journey back to Japan since the Meadow Garden was completed nine years ago and it is a privilege to be able to return to tune and evolve the planting. Each year my visits are timed to a slightly different week in the growing season. This year in the autumn to concentrate on a new layer of planting designed to extend the season to its limit. On my last day there a sharp wind from Siberia whipped over the mountains to toss the asters and the miscanthus and gave the mountain peaks their first showing of snow. The beginning of a winter that very soon will work its way into the garden to envelop it in a five-month eiderdown of whiteness. My visits have allowed me to build a bond with Midori Shintani, the more than capable head gardener. Without her the garden would not be possible and we are very lucky to be able to communicate and to discuss the nuances of the planting so easily. Through the garden we have become friends and, for the past few years, we have taken a few days after our annual workshops to visit other parts of Japan. Last year it was to see the studio and garden of my great hero Isamu Noguchi on the island of Shikoku, but this year we stayed in Hokkaido, driving west to the capital, Sapporo, to see Moerenuma Park the sculptor’s last, and posthumous, work. The construction of the site started in 1982 as a greenbelt initiative to convert a waste treatment plant into a place that people could use. Nestled into a bend in the river on the outskirts of the city, the park now extends to 183 hectares and the completed landscape took a total of 23 years to build. In 1988 Noguchi was approached by the city to design and masterplan the park. He first visited the site in July and presented his masterplan concept in the form of a three dimensional model in November. He died, aged 84, the same December.

It is a testament to the city and to the Noguchi Foundation that the masterplan was followed so rigorously, for it is a hugely ambitious project. I first saw it – only two years after it’s soft opening – in the winter of 2000 under a thick blanket of snow, which completely abstracted the landscape through its unification. The genius of the place is that the landscape is considered to be one complete sculpture and, under snow, you could see it as such, like one of his tabletop maquettes or a piece of origami, the scale without the reference of detail, the boundaries apparently limitless.

Returning to see it not only completed, but also green and still clothed in autumn, was no less surreal. It is a place that makes you feel very small and insignificant. It has a monumental quality as if Noguchi had catalysed a life’s work into something that is bigger than man. Bigger than he ever was when he was living, like an exploded ego. And he is everywhere.

The construction of the site started in 1982 as a greenbelt initiative to convert a waste treatment plant into a place that people could use. Nestled into a bend in the river on the outskirts of the city, the park now extends to 183 hectares and the completed landscape took a total of 23 years to build. In 1988 Noguchi was approached by the city to design and masterplan the park. He first visited the site in July and presented his masterplan concept in the form of a three dimensional model in November. He died, aged 84, the same December.

It is a testament to the city and to the Noguchi Foundation that the masterplan was followed so rigorously, for it is a hugely ambitious project. I first saw it – only two years after it’s soft opening – in the winter of 2000 under a thick blanket of snow, which completely abstracted the landscape through its unification. The genius of the place is that the landscape is considered to be one complete sculpture and, under snow, you could see it as such, like one of his tabletop maquettes or a piece of origami, the scale without the reference of detail, the boundaries apparently limitless.

Returning to see it not only completed, but also green and still clothed in autumn, was no less surreal. It is a place that makes you feel very small and insignificant. It has a monumental quality as if Noguchi had catalysed a life’s work into something that is bigger than man. Bigger than he ever was when he was living, like an exploded ego. And he is everywhere.

As we walked the site (and not yet knowing that he had died in the year he had visualised this landscape) and it being autumn and empty of people, the mood was already melancholy. We talked about feelings of death, infinity and the beyond as we tried to grapple with the sheer scale of it. We found ourselves pining for the activity of people and the laughter of children that had always been seen as an essential part of Moere Beach, which was unfortunately drained of water for repairs. Noguchi had wanted to bring the sea to Sapporo and this shallow pond paved with coral represents a beautiful seashore which sits on the edge of The Forest of Cherry Trees. The great wrap of cherries would be the scene of parties spread out under the blossoming at hanami. In the newly planted woods that wrap this extent of the site there are seven play areas which were designed so that, as the children lost interest in one game, they could move on to find another in the next clearing, animating the park as they went. Noguchi designed the play equipment to stand alone as brightly coloured sculptures, so that it did not matter that we were there in silence. It was good to feel the scale of things amplified by the emptiness.

As we walked the site (and not yet knowing that he had died in the year he had visualised this landscape) and it being autumn and empty of people, the mood was already melancholy. We talked about feelings of death, infinity and the beyond as we tried to grapple with the sheer scale of it. We found ourselves pining for the activity of people and the laughter of children that had always been seen as an essential part of Moere Beach, which was unfortunately drained of water for repairs. Noguchi had wanted to bring the sea to Sapporo and this shallow pond paved with coral represents a beautiful seashore which sits on the edge of The Forest of Cherry Trees. The great wrap of cherries would be the scene of parties spread out under the blossoming at hanami. In the newly planted woods that wrap this extent of the site there are seven play areas which were designed so that, as the children lost interest in one game, they could move on to find another in the next clearing, animating the park as they went. Noguchi designed the play equipment to stand alone as brightly coloured sculptures, so that it did not matter that we were there in silence. It was good to feel the scale of things amplified by the emptiness.

The park is dominated by two giant landforms. Mount Moere, a grass pyramid which rises to 62 metres, and the curiously named Play Mountain rising to 30 metres. Mount Moere brings a mountain into the city of Sapporo in another boldly elemental move. There is a direct route that stretches up in a perfect line to the summit and a beautifully drawn curve that allows you to traverse more gently, down a set of concrete steps on the other side. Though smaller, Play Mountain, which Noguchi first conceived in 1933 and contemplated over a long period, has a gravity and an ancient quality. At its base, the whiteness of Music Shell has a back-drop of a bank of dark conifers, so that you naturally stand on the stage of the performance space and look up. In front of you the mountain rises, one complete side stepped with granite sleepers. We joked as we ascended that it felt like we were on the way to a sacrifice. At the top (and only in Japan) a windswept bride and her groom were braving the elements for photographs.

The park is dominated by two giant landforms. Mount Moere, a grass pyramid which rises to 62 metres, and the curiously named Play Mountain rising to 30 metres. Mount Moere brings a mountain into the city of Sapporo in another boldly elemental move. There is a direct route that stretches up in a perfect line to the summit and a beautifully drawn curve that allows you to traverse more gently, down a set of concrete steps on the other side. Though smaller, Play Mountain, which Noguchi first conceived in 1933 and contemplated over a long period, has a gravity and an ancient quality. At its base, the whiteness of Music Shell has a back-drop of a bank of dark conifers, so that you naturally stand on the stage of the performance space and look up. In front of you the mountain rises, one complete side stepped with granite sleepers. We joked as we ascended that it felt like we were on the way to a sacrifice. At the top (and only in Japan) a windswept bride and her groom were braving the elements for photographs.

From the summit you look back to the conifer plantation which, it becomes clear, is helping the shakkei, (the borrowed view) by exactly echoing an outcrop in the mountain line in the distance. You then see the plantation is raised up on a great fold in the land with the angle of the crease retained by a wall the size of a castle rampart, also the same shape as the distant mountain. Below in the sunshine Tetra Mound glistens. Composed of a triangular steel pyramid and grassy mound designed to capture different expressions with the changing light, it too is vast when you descend and cross the endless lawn to see it.

From the summit you look back to the conifer plantation which, it becomes clear, is helping the shakkei, (the borrowed view) by exactly echoing an outcrop in the mountain line in the distance. You then see the plantation is raised up on a great fold in the land with the angle of the crease retained by a wall the size of a castle rampart, also the same shape as the distant mountain. Below in the sunshine Tetra Mound glistens. Composed of a triangular steel pyramid and grassy mound designed to capture different expressions with the changing light, it too is vast when you descend and cross the endless lawn to see it.

We moved on to the Glass Pyramid for tea and retreat. The pyramid, designed as Noguchi often did to contrast two materials, juxtaposes one opaque, the other transparent. It was conceived as a hidamari, a word that describes the spot where sunlight gathers. Sure enough the sun streamed in through the glass and the enclosure of the place gave respite from the relentlessness of scale outside. Our feeling of being overwhelmed was charged as much with excitement as it was with awe, but I have rarely felt so uncomfortable or challenged in a man-made landscape.

We moved on to the Glass Pyramid for tea and retreat. The pyramid, designed as Noguchi often did to contrast two materials, juxtaposes one opaque, the other transparent. It was conceived as a hidamari, a word that describes the spot where sunlight gathers. Sure enough the sun streamed in through the glass and the enclosure of the place gave respite from the relentlessness of scale outside. Our feeling of being overwhelmed was charged as much with excitement as it was with awe, but I have rarely felt so uncomfortable or challenged in a man-made landscape.

We finished the afternoon at the Sea Fountain. Held within a deep dark ring of conifers, the circular plaza centred on the last of Noguchi’s pieces to be completed at the park. He had long been fascinated by water as sculpture and birth, life and the heavens as inspiration. We arrived to find the vast cauldron boiling and churning like deep sea water when it is pushed into a ragged cliff. It was truly moving, the life we had been looking for and, then, joy as a halo of mist wrapped the crucible and then sent a geyser reaching way into the light to apparently connect with the clouds.

We finished the afternoon at the Sea Fountain. Held within a deep dark ring of conifers, the circular plaza centred on the last of Noguchi’s pieces to be completed at the park. He had long been fascinated by water as sculpture and birth, life and the heavens as inspiration. We arrived to find the vast cauldron boiling and churning like deep sea water when it is pushed into a ragged cliff. It was truly moving, the life we had been looking for and, then, joy as a halo of mist wrapped the crucible and then sent a geyser reaching way into the light to apparently connect with the clouds.

Words & photographs: Dan Pearson

Words & photographs: Dan Pearson The market gardens that originally striped the slopes here were given over to beef cattle about fifty years ago. The farmer had a dozen or so animals and the fields were grazed to the very edges. Lengths of rusty barbed wire kept them from venturing into the stream and pushing through the hedges, the branches on overhanging trees were cut back right to the boundaries and the hedges kept trim so that the ‘grub’ was given all the light it could get. The grass was everything.

Our first winter here we resolved to put a number of the fields back to meadow. This was not necessarily an easy decision, because the best flower meadows are the result of many years of appropriate husbandry: namely the removal of the hay crop, which diminishes soil fertility, followed by winter grazing by livestock. The high ground where the limestone brash broke through provided us with the best chance of diversity, while the lower ground grew grass that was lush and constantly emerald green. We found out from neighbours that our top fields above the lane (main image) had once been known as the Hospital Fields and that sickly cows were sent there to self-medicate on the plants that were good for them. Even before the fields were allowed to grow out the following summer, we could see here the knit of rosettes amongst the sward and the marked contrast in plant diversity compared to the lower ground

Yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor

Yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor

The next autumn we over-sowed these fields by hand with meadow seed gathered from the neighbouring valley. The seed is harvested annually from the well-established meadows of St. Catherine’s valley by Donald MacIntyre of Emorsgate Seeds and the technique of over-sowing enabled us to increase the diversity in our own fields without needing to disturb the ground. The key component in the seed mix is yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor, an annual which is semi-parasitic on grass. The rattle is invaluable for its ability to open up the sward by diminishing the strength of the grasses and thereby allowing the broadleaves – and most importantly our new seed sown directly into the existing sward – a window of opportunity to establish. Without it the over-sown seed would stand little chance of competing.

Yellow rattle is particular in its habits and needs to be sown between mid-September and Christmas at the very latest so that the frost can break the seeds’ dormancy. Winter ‘poaching’ of the fields by livestock presses the seed into the soil and makes for the best establishment, so we let the sheep into the fields to trample the ground and bring some mud to the surface. You can simulate this by first scarifying the thatch and then rolling the ground after sowing, but sheep do a better job and keep the grass short over winter, so that in March, when the rattle germinates, it has the head start it needs to get away early.

Oversown St. Catherine’s meadow mix behind the house after three years

Oversown St. Catherine’s meadow mix behind the house after three years

Trying to spot the seedlings the next spring became the stuff of obsession, both of us tramping the fields, heads bent, looking for the first distinctive serrated leaves, but Donald, who gave us the seed, said that for every one you see there are a hundred that you don’t. It was good advice, along with waiting until the 15th of July before cutting the hay, so that the rattle has the best chance to drop its seed. An old adage goes that when the rattle rattles the hay is ready for cutting and, sure enough,when it is ripe you will hear the seed rattling in the bladder-shaped seedpods . You can knock yellow rattle out of a meadow by cutting too early, as it is an annual and the seed is only viable for a year.

Increased floral diversity including ribwort plantain, black medick, red clover and pale flax

Increased floral diversity including ribwort plantain, black medick, red clover and pale flax

The following autumn we over-sowed The Tump, a field lower on the slopes and higher in fertility. The rattle has had a harder time here making its way into the grasses, but where it has taken we are seeing a greater and improved diversity of species. With every year we see the results in the wake of the yellow rattle with a notable presence of plantain, red clover, buttercup and rattle colonies in the second year. After five or six years the yellow rattle reaches a climax and starts to out-compete its host grasses and suddenly disappears to relocate elsewhere in the meadow. The results of the over-sowing have varied according to the differing ground conditions and it will take a decade before we really know whether the richer ground is suitable for supporting the species-rich meadow that should be possible on our thinner soil.

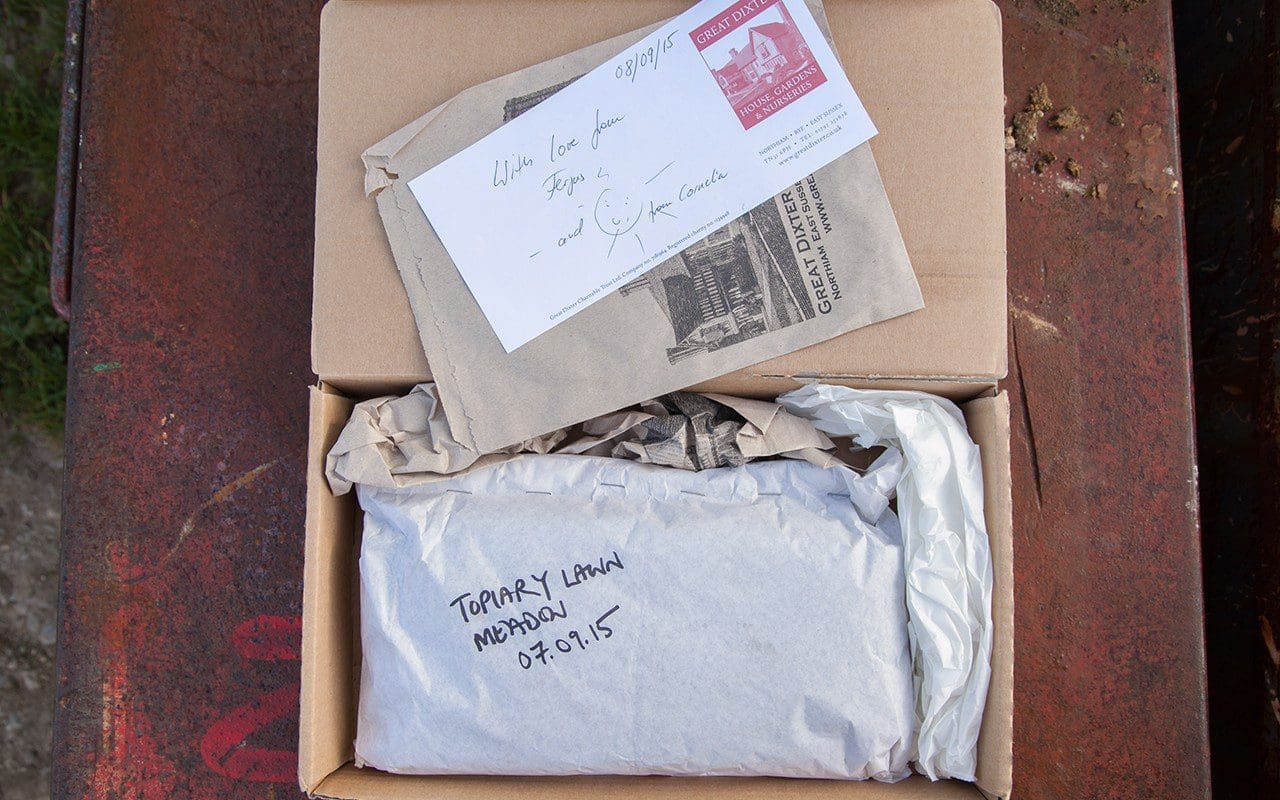

Package of Great Dixter meadow seed sweepings

Package of Great Dixter meadow seed sweepings

Over-sowing the Great Dixter meadow seed last September

Over-sowing the Great Dixter meadow seed last September

In year three, I sowed directly onto subsoil where we had stripped a level on the banks behind the house for topsoil. The newly sown ground has lower nutrient levels and sowing directly onto subsoil means that the strength of the grasses is automatically diminished. I made my first attempt to introduce orchids into this new area last September with a gift of the orchid-rich sweepings from the topiary meadow at Great Dixter, which were given in exchange for a lecture I gave there. Christo famously once responded to a request from a visitor that the meadow sweepings were not the sort of thing that money could buy, so it felt appropriate to barter. The contents of the package looked like nothing more than straw and dust, so I chose a still day to broadcast it and then let the sheep over the ground to crop the meadow short over the winter. If we are successful – a seven year wait will be necessary to see – it will be because there is a mycorrhiza in the ground that is symbiotic with the orchid roots and crucial to their establishment. A solitary pyramidal orchid blooms on the bank nearby, so I am ever hopeful.

Our solitary pyramidal orchid, Anacamptis pyramidalis

Our solitary pyramidal orchid, Anacamptis pyramidalis

This month, and to bring the meadows close, I have sown the newly contoured landforms around the house which have been made up with subsoil from the building works. After grading earlier this summer I deliberately left the ground dormant to flush out any weeds ahead of the meadow seed germinating and thereby diminishing competition from unwelcome interlopers. Annual weeds will be knocked out with a hoe and perennial weeds, such as creeping thistle and bindweed, selectively spot-treated with glyphosate. This and next month are the optimum time to sow, with heat in the ground from the summer and the promise of damp in the air to get the newly germinated seedlings established and knitting together before the onset of winter.

The yellow rattle seed gathered this year is broadcast to areas where the grass grows most strongly in the meadows

The yellow rattle seed gathered this year is broadcast to areas where the grass grows most strongly in the meadows

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

As the sun starts its descent towards autumn we are chasing it to Greece for a well-deserved holiday. By the time we return the spiders will be spinning, the apples will need picking and the garden will have begun it’s slow decline. We leave you with some late summer pictures of the garden at Hillside and the surrounding countryside to tide you over until we are back.

Photographs: Huw Morgan

It has been a good year for the hawthorn. It is foaming still up the hedge lines and cascading out of the woods above the stream at the bottom of the hill. We have gravitated there in the evening sunshine to stand at the bottom of the slope and marvel. The trees have been drawn up tall and slender and the froth of creamy flowers brightening the shadows of the newly sprung wood. At the margins of the wood, their favoured place, the branches push out wide and low, a hum of insects enticed by an uncountable sum of flower.The hawthorns saw the apples come and go and now they are starting to dim, it is summer. Why they were as weighted so heavily with flower this year I do not know, but it is the best they have been since we arrived here and I am pleased I have planted them as plentifully.

Haw, May, Quick, Quickset; hawthorn is a tree surrounded in folklore. Cut one and you will be plagued by fairies, but turn the milk with a twig before churning and you will protect the cheese from bewitchment. According to Teutonic legend, the tree originated from a bolt of lightning, which is why the wood was used on funeral pyres. The power of the sacred fire was sure to ferry your spirit to heaven.

In ancient rituals the hawthorn symbolised the renewal of nature and fertility, which often made it the choice for a maypole at Beltane. The wood itself is one of the hardest and often used for fine engraving and the young leaves are surprisingly delicious in a salad, with a fresh nutty taste.

The flowers, however, smell both sweet and stale. Some find this unpleasant, but to my nose it is just a country smell, which attracts flies and insects that lay their eggs on decaying animal matter. Crataegus is well known for the diversity of species that live within the thorny cage of its branches or on the bark or the foliage so, despite the superstition around it, it is a mainstay of the countryside.

I have relied upon it as the greater component when replanting my native mixed hedges. It is called Quick with good reason and the hedges that I planted to gap up our broken boundaries five years ago are already six feet high, thick and impenetrable. I wonder how elderly some of the thorns are in the oldest of the hedges here. It is estimated that 200,000 miles of them were planted between 1750 and 1850 as a result of the Enclosure Acts. During this time there were nurseries committed to growing the hawthorn in quantity to meet the demand, and making a small fortune from the supply.

If you leave your hedges and cut them year on, year off, the hawthorn flowers and fruits more heavily. Leave a tree free-standing and it will be reliably heavy with dark red berry in October. The berry is the way to propagate. I leave them for as long as I dare before taking my share, for the birds will suddenly strip a tree when the fruits ripen. The digestive juices of birds help to break the inbuilt dormancy of the seed, but you can simulate this by leaving the berries to ferment for a week in water before lining out in a drill in the garden. Some may germinate the following year after the action of frost has worked its magic, but two years of stratification may be required before you get a full row to germinate. Within a year of germinating you will have young plants a foot or so tall, in two whips ready to make a hedge. Or the beginnings of a maypole.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Before we arrived here the land had been grazed up tight to the hedges and to the farmyard, which held the cattle back from the house. That autumn, in a tiny strip of garden sandwiched between the front of the house and the concrete path to the door, blazed a clump of bright pink nerine and, the following spring, a slash of blue muscari marked what we later found to be the dog cemetery. Above the milking barn to the east a vegetable plot measuring four paces wide and double that down the slope was still in evidence. Raymond’s brother, Norman, had kept it cleared with a wonky-wheeled rotavator that coughed and spluttered black smoke and sported an arm held in place with baler twine. He tried to sell it to me with the advice that, to turn it off, it needed a thump with a broken-handled lump hammer. Needless to say I didn’t take him up on the offer.

Raymond’s vegetable garden when we first arrived

Raymond’s vegetable garden when we first arrived

When you arrive somewhere new, it is important to take the time to look. So the three loads of plants that I brought from the garden in Peckham were shoe-horned into my ration of cultivated ground. The ground, only tickled over by the rotavator, revealed a hard pan a couple of inches down and soil that had clearly not been improved for some time. But I was grateful, as it was free of weeds and provided me with the time to think.

“When you arrive somewhere new, it is important to take the time to look.”

Although it was clearly going to take time to decide how to make a garden here, I made a move in the first winter so as not to miss the planting season. It felt important to repair and reclaim boundaries so, over the Christmas holidays, we replanted a broken hedge on the west boundary, that was missing more teeth than it retained and removed the rickety barbed wire fences that stopped our eyes from seeing the stream below us sparkling in the low winter sunshine.

I walked the land daily, looking for the best location to plant a new orchard and took the lead from a dead stump in the field beyond the barns where our neighbour Glad said there had once been plums. We planted over thirty fruit trees here – apples, pears and plums – a hazel coppice at the base of the slope below them and, in the top corner of the field above, a blossom wood of natives to provide cover, shelter and food for birds. I also started the process of introducing more oaks, both as hedge trees and gate markers. The land felt in need of a new generation of trees and these were good moves to make straight away. After five years here we already have trees we can stand under, a complete and continuous hedge and the beginnings of a fruit and nut harvest.

Laying out the expanded garden in 2011

Laying out the expanded garden in 2011

The following spring I expanded the little vegetable plot, with a local farmer helping to turn in part of the field and partition the ground with a stock proof fence. I will write more on the balance between farming and gardening another time as it is a huge subject but, suffice to say, in our time here we have learned a great deal about sheep, their appetites and the importance of fences and tree-guards.

“The plot has reminded me of working on the trial beds when I was at Wisley…”

I sub-divided the plot with dirt paths into a series of beds that could be reached easily from either side with a hoe. It was a practical decision that freed me up to grow things in rows where they could be observed and easily tended. It was an easy way not to have to worry about aesthetics at this point, and to focus on identifying the best plants for the site. We were also growing vegetables and soft fruit on this same piece of ground, and so I enjoyed the discipline of the orderly rows, the unconscious reference they made to the former market gardens, and the liberation from the expectation that a garden must be a designed composition. The plot has reminded me of working on the trial beds when I was at Wisley and I have been free to observe and experiment in this laboratory.

In the first year the balance of plants favoured vegetables

In the first year the balance of plants favoured vegetables

Compared with Raymond’s old vegetable patch digging over the new ground was like turning cake mix. Where it has been converted from pasture, the soil is deep, dark and hearty and, that first summer, I understood why there had been market gardens here. Tilted at the perfect angle to receive the south facing light and exposed to it for as long as the sun shone, my garden grew like I’d never seen anything grow before. Sunflowers threw themselves at life, towering to over ten feet by the end of the summer. I grew fifty-six dahlias, because there was the space to absorb their flamboyance, and a collection of two-dozen David Austin roses, each lined out neatly, and easy to tend. I was able to devote a whole bed to peonies, one to lavenders and another to irises. All with the intention of watching and waiting to see which were most gardenworthy.

Some of the 56 varieties in the dahlia trial

Some of the 56 varieties in the dahlia trial

That first spring I sowed three separate panels of Nigel Dunnett’s Pictorial Meadows annual mixes. I had grown them in clients’ gardens, but had never had the space to experience growing them at close quarters for myself. It was like starting all over again. One world inside the fence, revealing itself through growing, another beyond revealed through a slow and informed process of looking and steering.

Black opium poppies and a Pictorial Meadows mix in year one

Black opium poppies and a Pictorial Meadows mix in year one

We quickly learned that gardening on a slope was hard work. Every move has to be negotiated with the incline, the push and the pull of manual labour considered very carefully. Knowing how much to fill the barrow and how to place it on the slope to avoid losing a load, which way to dig and which direction to hoe, how to place yourself to make weeding less strenuous, all were a whole new way of gardening for me, having always gardened on the flat. It is a windy site too. My daylilies from the sheltered garden in Peckham grew to half their height in the exposure of this sunlit hillside. The hellebores flagged without shelter, but everything that liked it stood solid and healthy as an athlete.

The functional arrangement of plants has produced some unexpected and exciting combinations

The functional arrangement of plants has produced some unexpected and exciting combinations

The garden grew, but at a price. Gradually, from nurseries, specialists, friends and plant fairs, I accumulated a collection of special martagon lilies, an assortment of asters, salvias and sanguisorbas and countless other treasures. So, rather predictably, my growing collection of herbaceous, flowering plants rapidly started to crowd out the vegetables, and I soon found myself planning a new vegetable garden with level ground and ease of access. We made a start in the third summer, forming a flat terrace to the west, extending the ridge that the buildings sit upon.

“I knew early on that I didn’t want to be able to see an ornamental garden from the house…”

In doing so, the spine of garden activity was taken out from the house, linking the practicality of vegetable and fruit growing to the barns and the newly planted orchard beyond. I knew early on that I didn’t want to be able to see an ornamental garden from the house, that looking into the complexity of a planting was something I wanted to choose to do, rather than have it demand my attention. So, with the vegetable garden positioned to the west, I am now planning to sweep the landscape up to the front door from the south and develop the gardened garden in a complementary span to the east.

The aster trial

The aster trial

As I write, at the end of our fifth winter here, I am surrounded by the aftermath of building works, which have seen us modernise the house and convert the milking barn into a studio where we can work. From here we look onto the ground that was once Raymond’s vegetable patch and, now that the battleground of construction has settled, and with five years of looking behind me, I am ready to make my move. The winter has seen me rationalising the stock beds of plants and we have just turned in a green manure crop of winter rye, so that soon, when the weather is dry enough to get on the land again, I will be able to start forming the garden. The survivors from those carloads of plants that arrived here from Peckham five years ago are finally ready to be found a home.

Dan and Ian turning in the winter rye

Dan and Ian turning in the winter rye

Words: Dan Pearson/Photographs: Huw Morgan

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN