ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

Bonfire night embers

Candy floss toffee apple

Flaming katsura

Words and photograph | Huw Morgan

Published 19 October 2019

We have been visiting the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido this last week. It was my annual visit to meet with Midori Shintani, the head gardener, to gauge the past year’s developments and help move the garden gently forward. Gardens are never static and the elemental nature of the surrounding forest and the backdrop of the Hidaka Mountains has a strong influence here. In 2016 a typhoon hit the forest, swelling the braided streams and charging them with boulders that swept away the footbridges. Miraculously the waters parted around the garden, but we have only just recovered from the influence. This past winter the eiderdown of snow was not as deep enough in parts to insulate all of the plants effectively and so the minus twenty degree winter has taken its toll in some areas.

Such are the challenges faced by Midori and her assistant head gardener, Shintaro Sasagawa, and when I arrived they were already well advanced on replanting the areas that had been worst affected. This year – for with contrary mountain weather every year is different – we found the garden in a cool, damp week. The cloud hung heavy to shroud the mountains and the Hokkaido drizzle bowed the perennials in the garden to the ground. The northern climate here compresses the summer so that it rushes fast in the growing season and, though the garden was pausing between the first flush of early summer and the coming wave of high summer colour, we saw significant change in the five days that we were there. Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’ starting to open its flame-red tapers and Cephalaria gigantea reaching ever taller over a river of Achillea ‘Coronation Gold’.

Huw accompanied me this year because we were also meeting to discuss the book I am currently writing to be published by Anna Mumford of Filbert Press next autumn. The richness of the Tokachi Millennium Forest and the way that it is being tended has a growing following and so the book feels timely. Midori is contributing to the book and one of the most important themes she will write about is the ancient Japanese tradition of satoyama – the practice of living in close harmony with and showing reverence for the land. A renewal of this approach, where the people make the place and the place makes the people, has been a central component in the genesis of the gardens.

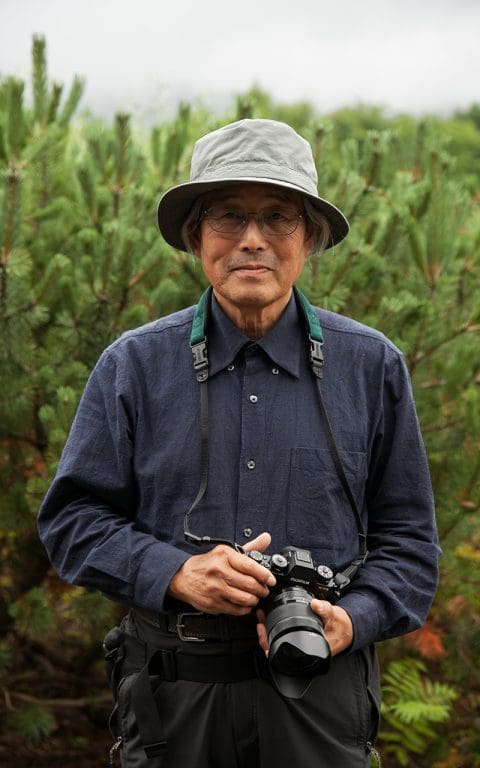

We met with Kiichi Noro, a highly respected landscape photographer in Japan, and a man of great humility who has been recording the forest and gardens for the last 5 years. He has delivered around 40,000 images, which need to be distilled to ensure that we capture the gardens and all the nuance of the forest influence throughout a working year. Huw has been working on the picture selection and look of the book with Julie Weiss who is designing it, and who also joined us in Hokkaido. Julie used to be an art director at Vanity Fair magazine before changing direction three years ago, since when she has immersed herself in the world of horticulture, working as a trainee gardener at Great Dixter and travelling to see and learn as much as she can.

We are also doing what we can to provide educational opportunities. Midori and I led a Garden Academy this week, spending an afternoon talking 40 attendees – many of whom had travelled from other cities in Japan, and one very keen group from Korea – through the principles of the Meadow Garden and how its sits alongside the gently tended forest that inspired the planting. Midori has also taken gardeners from Great Dixter on an exchange basis as well as student gardeners from around the world who have taken it upon themselves to write to her. This year there are three volunteer gardeners from overseas working in the garden to gain a deeper experience and understanding of Japanese gardening practice and culture in general. Two young English designers, Charlie Hawkes and Alice Fane, who are staying this year from snow melt to snow fall and Elizabeth Kuhn, a horticulturist and nurserywoman from America with a particular interest in the native flora.

The woodland is the ultimate inspiration for the way that everything is done here and I return to it constantly to provide me with focus. In the week we were there we watched it moving through its final peak before dimming now that the canopy of magnolia and oak has closed over. Stands of Cardiocrinum cordatum var. glehnni stood tall and luminous to scent the pathways. The glowing purple spires of Veronicastrum sibiricum var. yezoense stood sentry at the forest edge. The vestiges of Trillium and earlier flowering Anemone and Glaucidium are already in the shadow of the Angelica ursina which were pushing up in a last great bolt of energy to flower. Most had not yet reached their full height, but those that had broken into flower stood twelve feet high with the parasols of Petasites japonicus ssp. giganteus at their feet.

Walking through the forest was as spellbinding as ever and you cannot help but feel charged by the experience of being there. Now all we have to do is try to capture that on the page so that the forest reaches beyond its boundaries, as it should.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 20 July 2019

A month ago I was in Japan, on my annual visit to the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been working at the forest for sixteen or seventeen years now and the yearly journey is always rewarding. It is a place with a big vision, where half the side of a mountain and the forested foothills are the domain. It has the feeling of the north, with air that slips over the mountains from Russia not so far away. Bears really do live in the woods and the landscape freezes to minus twenty-five, under a blanket of pristine white from early November through to the end of April.

The owner, Mitsugishe Hyashi, bought the land with the ambition of offsetting the carbon footprint of his newspaper business, but the park represents far more than this. He also set out for it to be sustainable for the next thousand years and it is a privilege to have been part of this vision and to be a small part in shaping the park’s direction.

The gardens and the managed forests are a big part of helping to communicate the big idea to visitors. The gently managed places, which take the rough edges off the wilderness, are part of making people feel comfortable in the areas that are accessible. Takano Landscape Planning, which put together the original masterplan, knew that the people and their comfort in the environment were important and, when I was asked to be part of the project in 2000, it was to help with creating a series of spaces that would provide the landscape with a focus for the public.

The Earth Garden

The Earth Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Goat Farm and Farm Garden at the end of the Meadow Garden

The Rose Garden

The Rose Garden

In their turn, the gardens we have since created have been key in making a ‘safe’ place and a link with the magnitude of the landscape, to literally ground the visitor in the place. A landform called the the Earth Garden, which reconfigured a clearance field that separated the visitor from the mountains, was the first of the projects to come to fruition. A series of grassy waves, echoing the undulations of the mountains beyond, now provides the visitors with a ‘way into’ the landscape. By exploring the earthworks they soon find themselves at the base of the mountains or at the edge of a mountain stream or a trail into the woods. The landforms extend to wrap another five hectares of cultivated garden, and area named the Meadow Garden, which was planted to celebrate the official opening ten years ago. Beyond that there is the Farm Garden where people can see a modestly-sized productive space with fruit, vegetables and cutting flowers and eat food grown there at the cafeteria. A goat farm producing cheese is the backdrop to this space, while most recently we have developed a Rose Garden of hybrid and species roses suitable for a northern climate and an orchard to test growing apples and other top fruit this far north.

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest

The Entrance Forest, where Fumiaki Takano had already made a start when I was brought on board, eases visitors in with soft bark paths and decked walkways that take them back and forth across the rush of mountain water that switches between the trees. The low native bamboo Sasa palmata, which took over the forest after its balance was disturbed when all of the oak was logged at the turn of the last century, has been carefully managed to encourage a more diverse regeneration of the forest floor. Repeated cutting in the autumn, coupled with the short summers that curtail its regrowth and stranglehold, has been diminished enough for the window of opportunity to be given back to other plants in the native seedbank. Wave upon wave of indigenous plants now greet the visitors. Anemone, Caltha palustris var. nipponica and Lysichiton camtschatcense seize the window after snow melt and, as oak woodland comes to life, the race continues with Trillium, scented-leaved and candelabra primulas and arisaema. By the time I arrived in late July, the woodland was tall with giant-leaved meadowsweet, cardiocrinum and lofty Angelica ursina.

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Lysichiton camtschatcense

Filipendula camtschatica

Filipendula camtschatica

The Meadow Garden (main image), my primary focus with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani, was inspired by the woodland and the way the plants have found their niche and live together in successive layers of companionship. Sitting on the fringes of the wood where dappled light meets sunshine, it is divided into two main parts by a meandering wooden walkway. The lower areas emulate the edge of woodland habitats, while above the path the planting basks in full sunshine. The planting is further divided by swathes of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, which separate the different colour fields, so that the yellows are held back as a surprise. The movement of the mountain winds is caught in their plumage to animate the garden.

The plantings integrate Japanese natives with plants from other regions of the world that have similar climates. North America and parts of northern Europe provide the ‘exotic’ layer in the garden and their inclusion draws attention to the Japanese natives that are mingled amongst them. Plants such as the Houttuynia cordata, Hakonechloa macra and Aralia cordata. Everyday plants in Japan that are given a new focus. In terms of my own gardening process, these plants were the exotics and it has been such a fascinating process to reverse my experience of the exotic/native balance. Native Lilium auratum, the Golden-Rayed Lily of Japan, and the giant meadowsweet, Filipendula camtschatica, are teamed with Phlox paniculata ‘David’. Sanguisorba hakusanensis, the extraordinary pink, tasselled burnet is in company with Valeriana officinalis and Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’.

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with ground cover of Hakonechloa macra and Houttuynia cordata

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

The woodland edge of the Meadow Garden with Lilium auratum and Phlox paniculata ‘David’

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis, Astrantia major ‘Hadspen Blood’ and Valeriana officinalis

The original planting plans were designed as a number of individual mixes, planted in drifts to allow the planting to flow across the site. Each mix contained a small number of species, usually five to seven, that were planted completely randomly. The percentages in the mix were critical, with a small number of emergent plants such as the Cephalaria gigantea to rise above larger percentages of individuals that would knit and mingle at lower and mid-level. Now that I look back it was a brave move, because it was entirely dependent upon the head gardener to steer and monitor.

Midori has been more than I could have hoped for in an ally on the ground and our yearly critique and analysis of the plantings is a high level conversation that looks both at the big picture and also at the detail. Of course, there have been adjustments to refine each mix as they change yearly with plant lifespans, climate and vigour, which drive our response. But we have also needed to make changes to keep the garden moving forward, introducing new plants and swapping or reducing the numbers of those which have become dominant. For instance, we have found plants that will happily coexist in a demanding matrix of twenty five companions in the wild, can take their opportunity to dominate when given just a handful of company.

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Persicaria polymorpha and Gillenia trifoliata

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Dan placing new additions of Lilium henryi with Head Gardener, Midori Shintani

Last year, to challenge the thousand year brief of sustainability, a tornado swept across the island. It hit last summer, just before I visited and I arrived to see the carnage. The mountain water had swelled the streams that braid the site to rip and tear and deposit a silver sand from afar and boulders that are now new features. Miraculously the waters divided to either side of the Meadow Garden, but they swept away all but two of the bridges, which have never been found. We were left feeling very small and of little consequence within the time frame that had been set for the preservation of this place.

The repairs have been slow but sure and in scale with what is possible. New shingle banks have been embraced as the new places and opportunities that they are. Already they are being colonised. It is the gardener’s way to repair and to move on, but we have been humbled nevertheless. Midori walked me through the garden, pointing out ‘weeds’ that have been swept in to the planting that were never there before. And there are anomalies that are hard to get to grips with that point to changes of another scale. Some plants have taken a hit a year later to sulk or fail, and we do not know why, whilst others have seized life with a new vigour as if the charge from the mountain has revitalised them. With ten years under our belts and the knowledge we have gained that is specific to this place, we are adjusting again and moving on. On to a second decade and the certain changes that we will be responding to, to move with it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Kiichi Noro and Syogo Oizumi

Published 16 September 2017

I have just returned from my annual visit to the Millennium Forest in Hokkaido. I have been making the journey back to Japan since the Meadow Garden was completed nine years ago and it is a privilege to be able to return to tune and evolve the planting. Each year my visits are timed to a slightly different week in the growing season. This year in the autumn to concentrate on a new layer of planting designed to extend the season to its limit. On my last day there a sharp wind from Siberia whipped over the mountains to toss the asters and the miscanthus and gave the mountain peaks their first showing of snow. The beginning of a winter that very soon will work its way into the garden to envelop it in a five-month eiderdown of whiteness. My visits have allowed me to build a bond with Midori Shintani, the more than capable head gardener. Without her the garden would not be possible and we are very lucky to be able to communicate and to discuss the nuances of the planting so easily. Through the garden we have become friends and, for the past few years, we have taken a few days after our annual workshops to visit other parts of Japan. Last year it was to see the studio and garden of my great hero Isamu Noguchi on the island of Shikoku, but this year we stayed in Hokkaido, driving west to the capital, Sapporo, to see Moerenuma Park the sculptor’s last, and posthumous, work. The construction of the site started in 1982 as a greenbelt initiative to convert a waste treatment plant into a place that people could use. Nestled into a bend in the river on the outskirts of the city, the park now extends to 183 hectares and the completed landscape took a total of 23 years to build. In 1988 Noguchi was approached by the city to design and masterplan the park. He first visited the site in July and presented his masterplan concept in the form of a three dimensional model in November. He died, aged 84, the same December.

It is a testament to the city and to the Noguchi Foundation that the masterplan was followed so rigorously, for it is a hugely ambitious project. I first saw it – only two years after it’s soft opening – in the winter of 2000 under a thick blanket of snow, which completely abstracted the landscape through its unification. The genius of the place is that the landscape is considered to be one complete sculpture and, under snow, you could see it as such, like one of his tabletop maquettes or a piece of origami, the scale without the reference of detail, the boundaries apparently limitless.

Returning to see it not only completed, but also green and still clothed in autumn, was no less surreal. It is a place that makes you feel very small and insignificant. It has a monumental quality as if Noguchi had catalysed a life’s work into something that is bigger than man. Bigger than he ever was when he was living, like an exploded ego. And he is everywhere.

The construction of the site started in 1982 as a greenbelt initiative to convert a waste treatment plant into a place that people could use. Nestled into a bend in the river on the outskirts of the city, the park now extends to 183 hectares and the completed landscape took a total of 23 years to build. In 1988 Noguchi was approached by the city to design and masterplan the park. He first visited the site in July and presented his masterplan concept in the form of a three dimensional model in November. He died, aged 84, the same December.

It is a testament to the city and to the Noguchi Foundation that the masterplan was followed so rigorously, for it is a hugely ambitious project. I first saw it – only two years after it’s soft opening – in the winter of 2000 under a thick blanket of snow, which completely abstracted the landscape through its unification. The genius of the place is that the landscape is considered to be one complete sculpture and, under snow, you could see it as such, like one of his tabletop maquettes or a piece of origami, the scale without the reference of detail, the boundaries apparently limitless.

Returning to see it not only completed, but also green and still clothed in autumn, was no less surreal. It is a place that makes you feel very small and insignificant. It has a monumental quality as if Noguchi had catalysed a life’s work into something that is bigger than man. Bigger than he ever was when he was living, like an exploded ego. And he is everywhere.

As we walked the site (and not yet knowing that he had died in the year he had visualised this landscape) and it being autumn and empty of people, the mood was already melancholy. We talked about feelings of death, infinity and the beyond as we tried to grapple with the sheer scale of it. We found ourselves pining for the activity of people and the laughter of children that had always been seen as an essential part of Moere Beach, which was unfortunately drained of water for repairs. Noguchi had wanted to bring the sea to Sapporo and this shallow pond paved with coral represents a beautiful seashore which sits on the edge of The Forest of Cherry Trees. The great wrap of cherries would be the scene of parties spread out under the blossoming at hanami. In the newly planted woods that wrap this extent of the site there are seven play areas which were designed so that, as the children lost interest in one game, they could move on to find another in the next clearing, animating the park as they went. Noguchi designed the play equipment to stand alone as brightly coloured sculptures, so that it did not matter that we were there in silence. It was good to feel the scale of things amplified by the emptiness.

As we walked the site (and not yet knowing that he had died in the year he had visualised this landscape) and it being autumn and empty of people, the mood was already melancholy. We talked about feelings of death, infinity and the beyond as we tried to grapple with the sheer scale of it. We found ourselves pining for the activity of people and the laughter of children that had always been seen as an essential part of Moere Beach, which was unfortunately drained of water for repairs. Noguchi had wanted to bring the sea to Sapporo and this shallow pond paved with coral represents a beautiful seashore which sits on the edge of The Forest of Cherry Trees. The great wrap of cherries would be the scene of parties spread out under the blossoming at hanami. In the newly planted woods that wrap this extent of the site there are seven play areas which were designed so that, as the children lost interest in one game, they could move on to find another in the next clearing, animating the park as they went. Noguchi designed the play equipment to stand alone as brightly coloured sculptures, so that it did not matter that we were there in silence. It was good to feel the scale of things amplified by the emptiness.

The park is dominated by two giant landforms. Mount Moere, a grass pyramid which rises to 62 metres, and the curiously named Play Mountain rising to 30 metres. Mount Moere brings a mountain into the city of Sapporo in another boldly elemental move. There is a direct route that stretches up in a perfect line to the summit and a beautifully drawn curve that allows you to traverse more gently, down a set of concrete steps on the other side. Though smaller, Play Mountain, which Noguchi first conceived in 1933 and contemplated over a long period, has a gravity and an ancient quality. At its base, the whiteness of Music Shell has a back-drop of a bank of dark conifers, so that you naturally stand on the stage of the performance space and look up. In front of you the mountain rises, one complete side stepped with granite sleepers. We joked as we ascended that it felt like we were on the way to a sacrifice. At the top (and only in Japan) a windswept bride and her groom were braving the elements for photographs.

The park is dominated by two giant landforms. Mount Moere, a grass pyramid which rises to 62 metres, and the curiously named Play Mountain rising to 30 metres. Mount Moere brings a mountain into the city of Sapporo in another boldly elemental move. There is a direct route that stretches up in a perfect line to the summit and a beautifully drawn curve that allows you to traverse more gently, down a set of concrete steps on the other side. Though smaller, Play Mountain, which Noguchi first conceived in 1933 and contemplated over a long period, has a gravity and an ancient quality. At its base, the whiteness of Music Shell has a back-drop of a bank of dark conifers, so that you naturally stand on the stage of the performance space and look up. In front of you the mountain rises, one complete side stepped with granite sleepers. We joked as we ascended that it felt like we were on the way to a sacrifice. At the top (and only in Japan) a windswept bride and her groom were braving the elements for photographs.

From the summit you look back to the conifer plantation which, it becomes clear, is helping the shakkei, (the borrowed view) by exactly echoing an outcrop in the mountain line in the distance. You then see the plantation is raised up on a great fold in the land with the angle of the crease retained by a wall the size of a castle rampart, also the same shape as the distant mountain. Below in the sunshine Tetra Mound glistens. Composed of a triangular steel pyramid and grassy mound designed to capture different expressions with the changing light, it too is vast when you descend and cross the endless lawn to see it.

From the summit you look back to the conifer plantation which, it becomes clear, is helping the shakkei, (the borrowed view) by exactly echoing an outcrop in the mountain line in the distance. You then see the plantation is raised up on a great fold in the land with the angle of the crease retained by a wall the size of a castle rampart, also the same shape as the distant mountain. Below in the sunshine Tetra Mound glistens. Composed of a triangular steel pyramid and grassy mound designed to capture different expressions with the changing light, it too is vast when you descend and cross the endless lawn to see it.

We moved on to the Glass Pyramid for tea and retreat. The pyramid, designed as Noguchi often did to contrast two materials, juxtaposes one opaque, the other transparent. It was conceived as a hidamari, a word that describes the spot where sunlight gathers. Sure enough the sun streamed in through the glass and the enclosure of the place gave respite from the relentlessness of scale outside. Our feeling of being overwhelmed was charged as much with excitement as it was with awe, but I have rarely felt so uncomfortable or challenged in a man-made landscape.

We moved on to the Glass Pyramid for tea and retreat. The pyramid, designed as Noguchi often did to contrast two materials, juxtaposes one opaque, the other transparent. It was conceived as a hidamari, a word that describes the spot where sunlight gathers. Sure enough the sun streamed in through the glass and the enclosure of the place gave respite from the relentlessness of scale outside. Our feeling of being overwhelmed was charged as much with excitement as it was with awe, but I have rarely felt so uncomfortable or challenged in a man-made landscape.

We finished the afternoon at the Sea Fountain. Held within a deep dark ring of conifers, the circular plaza centred on the last of Noguchi’s pieces to be completed at the park. He had long been fascinated by water as sculpture and birth, life and the heavens as inspiration. We arrived to find the vast cauldron boiling and churning like deep sea water when it is pushed into a ragged cliff. It was truly moving, the life we had been looking for and, then, joy as a halo of mist wrapped the crucible and then sent a geyser reaching way into the light to apparently connect with the clouds.

We finished the afternoon at the Sea Fountain. Held within a deep dark ring of conifers, the circular plaza centred on the last of Noguchi’s pieces to be completed at the park. He had long been fascinated by water as sculpture and birth, life and the heavens as inspiration. We arrived to find the vast cauldron boiling and churning like deep sea water when it is pushed into a ragged cliff. It was truly moving, the life we had been looking for and, then, joy as a halo of mist wrapped the crucible and then sent a geyser reaching way into the light to apparently connect with the clouds.

Words & photographs: Dan Pearson We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage

Words & photographs: Dan Pearson We are sorry but the page you are looking

for does not exist.

You could return to the homepage