ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

It was exactly a year ago, in the first week of lockdown, that we committed to buying a polytunnel. That same week I placed a very late seed order primarily for tomatoes, but some chillis, aubergines and cucumbers came too and we started them off indoors at the end of March. This late start was further compounded by the delayed arrival of the polytunnel itself, so that the seedlings intended for it had to be held back by hardening them off in a makeshift structure of seed trays and pieces of glass, since the cold frames were full. Although they got a little leggy and had to be watched carefully to ensure their 9cm pots did not dry out, they escaped the very late frost we had on May 12th and were finally planted into their grow bags in the first week of June.

This year I sowed the tender veg a full month earlier in late February, starting them off on the airing rack above the kitchen range before moving them to a warm windowsill as soon as they started to germinate. We are always keen to try new varieties and this year, alongside our old favourites ‘Gardener’s Delight’ and ‘Sungold’, I made a selection from Real Seeds based on productivity and hardiness, and also a range from very earlies to lates to see if we can stretch the season and push the tomato harvest into early winter. ‘Amish Paste’ is a heavy-cropping, extra-large preserving tomato, which I am trying instead of ‘San Marzano’, ‘Feo di Rio Gordo’, a deeply ribbed Spanish beefsteak variety that is reputedly very early for its size, while two Ukrainian varieties, ‘Purple Ukraine’ and the peach-fleshed ‘Lotos’, have late seasons, the latter with a reputation as one of the latest-cropping tomatoes, with fruit still pickable in late December.

Last year’s aubergines suffered from not being planted out soon enough and failed in the frames so, determined to have a crop this year, we have three varieties on trial; ‘Black Beauty’, which has a reputation as the most reliable cropper in the UK climate, which it seemed to prove by being the first and most profligate to germinate and with the largest, heartiest seedlings. Germination of the other two varieties – ‘Tsakoniki’, a Greek heirloom variety and ‘Rotonda Bianca Sfumata di Rosa’, both from Thomas Etty – was a little patchier, but we have enough seedlings to have three plants of each and still have some left to give away to friends and neighbours.

As well as new chillis ‘Basque’ and ‘Chilhuacle Negro’ I have succeeded in germinating the seed of some tiny superheat red chilli bought at Kos market two summers ago and I’m trying sweet peppers for the first time (‘Kaibi Round No. 2’ and ‘Amanda Sweet Wax Pepper’, also from Real Seeds) as well as two varieties of melon (‘Petit Gris de Rennes’ and ‘Charentais’), which I’m hoping will get enough light and heat to provide us with something truly exotic in the fruit department this year. All of the above were sown in the last week of February and they are all, bar the melons, ready to be pricked out into larger pots this weekend.

The delay in planting out last year had a continuing knock-on effect, and the last of the tomatoes were harvested in late October so that we could remove the grow bags (which were were last year’s quick fix) to build four raised beds. These allowed us to build up the level and enrich the soil of the unimproved pasture on which the polytunnel is sited with well rotted manure. We intend to practice no dig with these beds and so the retaining edge will help to keep things tidy.

Although I had sown a variety of oriental greens, winter salads, chard, kale and soft herbs from the beginning of September and into October and November it soon became apparent that this was also too late since, by the time the raised beds were finished in early November, the days had shortened to the point that none of the seedlings would make no further growth before the end of the year. These plug plants sat rather reproachfully in the cold polytunnel until late January, when I finally planted them out as the days slowly started to lengthen. However, they have now been providing us with salad and greens for two weeks or more and have more parsley, coriander and dill than we know what to do with.

Despite the late start what has become immediately apparent is that, with well-timed sowing and transplanting, the polytunnel will allow us to close the ‘hungry gap’ of late winter and early spring. In addition to salad and oriental greens there has been a seamless handover from the waning kale and turnip greens in the kitchen garden to those that were sown in plugs in late November and have now taken up the baton. With this knowledge I am now planning two late summer sowings of winter greens and salads, turnips and beets for late July and late August to take us through the season. I started my first salad, beetroot and kohl rabi sowings off in the tunnel this year and they have responded well to the warmth and even light, but we are also planning to build a hotbed in the polytunnel this winter so that we can get even further ahead with early sowings and keep our most tender seedlings warm at night.

Alongside planning for future winter crops this is now the time to get moving outside. The broad beans that I sowed in modules in early March in the polytunnel have been hardened off for a couple of days this week, ready to be planted outside. And it is potato and onion weekend. The potatoes have been chitting in egg trays in the tool shed for the past three weeks or so and will be going into newly dug ground that we have enclosed around the polytunnel. This will free up more space in the kitchen garden to get a better successional rotation going, as well as allowing us to extend the range of vegetables we can grow, like Jerusalem artichokes which are very space hungry and freezer harvest crops like the ‘Cupidon’ beans of which we can eat any amount.

And I will also be pricking out the tomatoes, which is where this all started. Holding them carefully by their first cotyledons I will extricate their roots from one another, acutely aware of the time, energy and care that has got them this far. I will move slowly and carefully so that none are wasted. I will lower them into the soil of their own pots, give them a drink and then leave them to get on with it until it is their time to take the stage again.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 27 March 2021

Yesterday we had our first snow. Just the briefest flurry, and it was too wet and warm for it to settle, but snow all the same. The colder weather demands something warm and hearty in the stomach and has finally given me the opportunity to make a long-planned silky soup from the coco beans that have been in the freezer since I harvested them over a month ago.

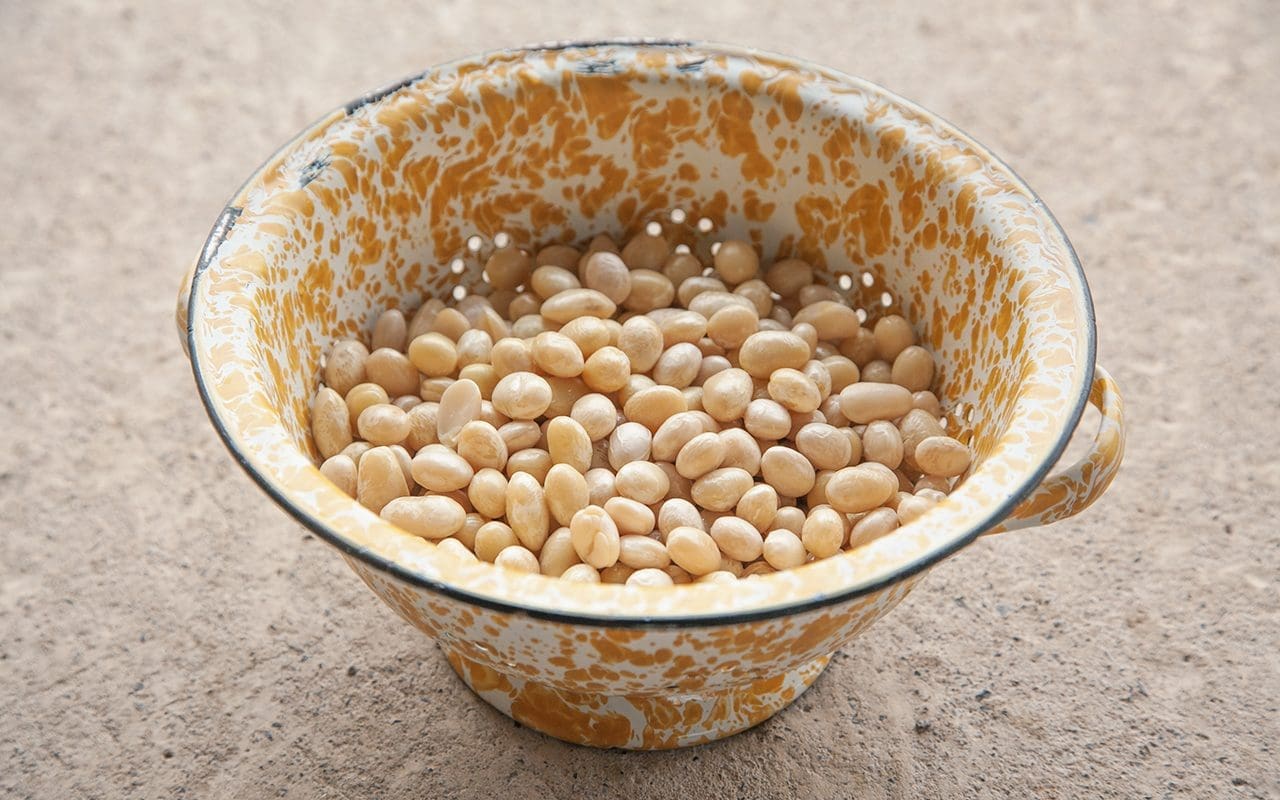

To date we have only ever grown climbing beans to eat fresh, but this year we grew a range of new beans, some of which I selected specifically for storing. At the end of the summer the bean which had cropped most heavily was ‘Coco Sophie’, a late 18th century variety which became commercially unavailable in 2006, and has only recently been re-introduced by The Real Seed Company. Due to the variety and quality of their seed, it has fast become our go-to seed supplier.

Coco beans are an old French large haricot type, producing shiny, round, creamy white beans with a texture comparable to normal haricot or cannellini beans. However, they are smoother and richer than either. The Coco de Paimpol, which is grown only in Brittany, has its own appelation d’origine contrôlée due to its incomparable texture and flavour. Although I had eaten coco beans in restaurants before and been struck by their silky texture, I had not, until this year, been able to find seed to grow them myself.

I picked the beans when semi-dry – which cuts down their cooking time significantly – and froze them immediately. However, they can be fully dried and then soaked before cooking. If using dried beans for this recipe 400g of dried beans will give a soaked weight of approximately 800g and, although you do not need to sieve the soup, it produces a superior result that is worth the little additional effort.

In my mind I had a velvety smooth, garlic-laden puree flavoured with woody herbs and a whiff of truffle. I had a recollection of having eaten something similar many years ago in Milan, as I associate it with distinct memories of risotto alla milanese, osso buco and whole pan-fried porcini.

A whole bulb of garlic may seem too much initially, but since it is simmered in the stock its strength is tempered and sweetened. The seasonal combination of sage and bay is warm and aromatic. Although we have several types of sage growing here, the most robust and best-flavoured variety is known simply as ‘Italian’, with large silver-grey leaves that are winter hardy and perfect for frying.

Serves 6

3 large leeks, white and pale green parts only, about 250g

3 tbsp olive oil

800g fresh or cooked white beans

1 bulb garlic

2 large sprigs of sage

1 large bay leaf

1.5 litres water or vegetable stock

Freshly grated nutmeg

Salt

Ground white pepper

12 large sage leaves

3 tbsp olive oil

Truffle oil

Heat the olive oil in a large pan over a low heat. Wash, peel and trim the leeks and slice them finely. Put them into the pan, put the lid on and sweat over a low heat for 10 to 15 minutes until translucent. Stir occasionally.

Peel and trim the garlic cloves and leave whole. When the leeks are cooked add the garlic, beans, sage, bay leaf and grated nutmeg to the pan with the water or stock. Bring to the boil and then reduce to a simmer. Cook with the lid on until the beans are soft; about 20 minutes if fresh, or 40 if dried and soaked.

When the beans are done remove the sage and bay leaves, then liquidise the beans and their cooking liquid with a stick blender until smooth. Then, if you want the silkiest smooth soup, push the puree through a fine sieve with the back of a metal spoon. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

In a small frying pan heat the second lot of olive oil. When smoking, fry the sage leaves in batches for about 10 seconds until crisp and just beginning to brown. Remove from the oil onto a piece of kitchen paper.

Ladle the soup into warm bowls. Drizzle over a little truffle oil and garnish each bowl with two fried sage leaves.

Recipe & Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 16 November 2019

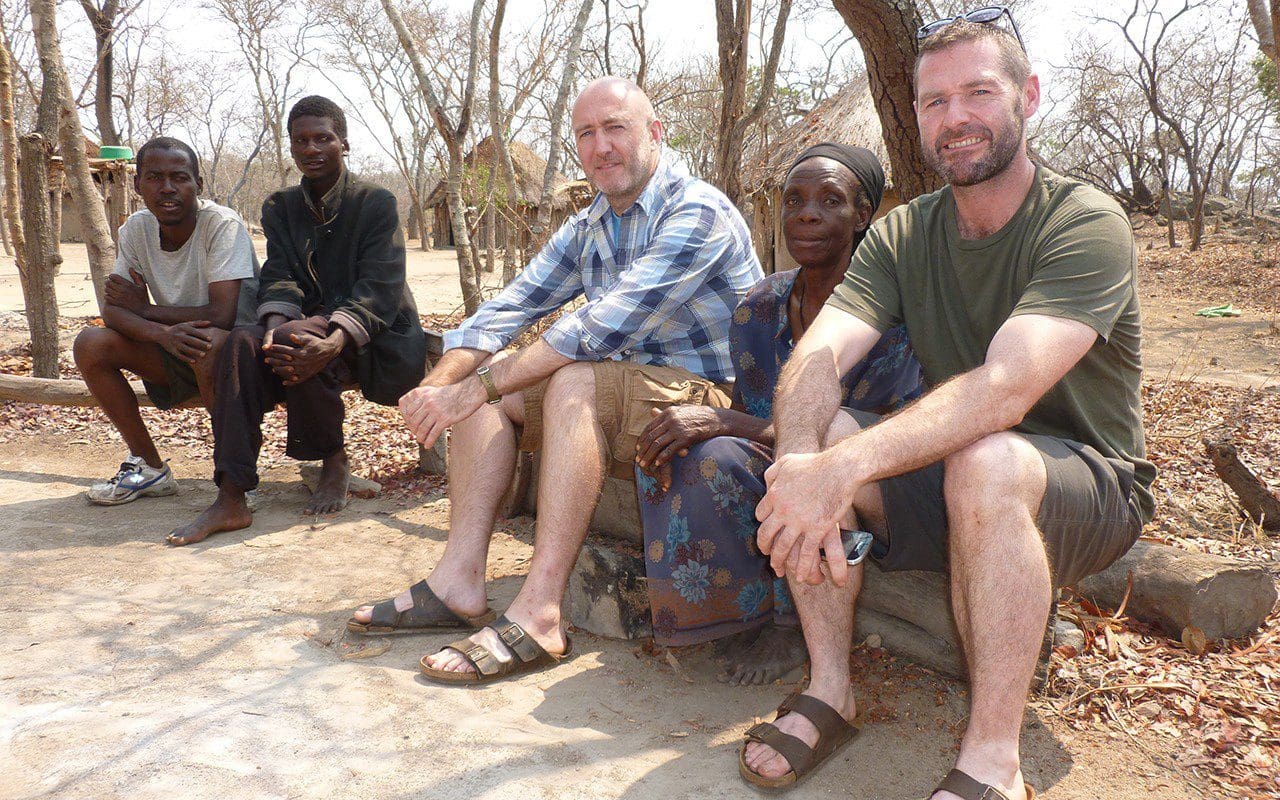

Simon Jackson (above right) is a pharmacognosist and cosmetician who is passionate about creating personal products that are derived from scientifically proven, sustainably produced active plant extracts. After a long and wide-ranging career as a scientist, researcher and cosmetic product innovator, for the past two years he and his husband, John Murray (above left), have been developing a new range, Modern Botany, using British native plants grown near their home in the West of Ireland. Simon, you have taken an interesting and varied route to where you are now. Can you give us a brief explanation of where your interest in the therapeutic uses of plants started and your training ? Interesting? Varied? I think they call it a career portfolio nowadays! OK, how long do we have? As you can imagine I’ve got a lot to say on plants and their therapeutic uses. I guess it all started in Lincolnshire. I grew up in a small village and my love of plants came from my grandmother, Cath Jackson. She was a keen amateur gardener and she taught me all the Latin names of plants when I was very young. She had a small plot of land and was very proud of all her plants and I used to help her gardening. She had a beautiful allium that came up year after year, and it was quite unusual in the early ‘70’s to have such unusual plants. She introduced me to Sir Joseph Banks, a famous Lincolnshire botanist. There is a big monument to him in Lincoln Cathedral, and his home town of Horncastle was close by, so the seed was planted. Skip forward about 20 years, and I found myself studying at Manchester Metropolitan University in 1989. I did a course in Applied Biological Sciences and specialised in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. Back in the late ‘80’s it was called Plant Defence Mechanisms. When plants are put under pressure externally or attacked by herbivores, they excrete defence chemicals. Salicylic acid is one of them. It has a bitter taste so wards off any herbivores, but it also has medicinal properties for humans too. Aspirin we call it. It was here that I learnt about ethnobotany, and how traditional cultures use plants. For example, it was the native Americans who used willow bark during childbirth as an analgesic to help with pain relief. I just thought this was amazing and so, as part of my degree, I undertook an expedition to Indonesia. The year was 1992, and it was in the middle of all the atrocities in Timor, but I was quite gung-ho even back then, and just wanted to learn more about plants and their traditional uses. We lived on an island called Sumba. It was very primitive back then, no luxury hotels or surf dudes like there are now, but I took part in what was one of the first pharmacy conservation projects in an Indonesian primary rainforest. I was cataloguing species of plants around the island and understanding from the locals any economic uses they had, which could be medicinal, or as dyes or fuel or even as building materials. The aim was to set up some sustainable practices for harvesting these plants. It was on the island of Sumba that I remember being introduced to a village chief. I had wandered off into the rainforest one day a bit too far on my own away from base camp, and he found me walking in the wrong direction (I have a terrible sense of direction) and brought me back to camp on the back of his Sumbanese pony, an indigenous breed of horse on the island. Seeing the hornbills flying back at dusk and the Sumbanese green pigeons (they look like parrots) it was here that I learnt from him about the traditional uses of plants, and it was here that I had my cathartic moment and realised it was traditional plants I wanted to study. That’s why I had majored in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. I also worked in the Herbarium in Bogor, and met Professor Kostermans, an amazing ethno-botanist, who regaled me with all his stories of expeditions in Indonesia, Borneo and Sumatra. He was a POW during the war and only survived by learning from the locals how to utilise the native plants for food and medicine. And that was it. I was hooked. Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

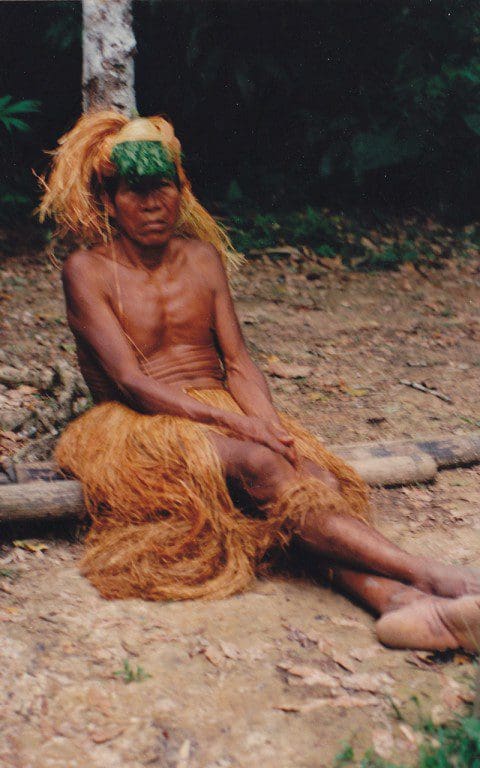

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

The ACEER Camp in Peru

The ACEER Camp in Peru

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

Kigelia pinnata fruit

Your first venture into therapeutic cosmetic products derived directly from plant extracts was with Dr. Jackson’s. How did that come about ?

I guess I had been observing how natural products were starting to become a global trend in cosmetics. We have a term called cosmeceuticals, which describes something that is part cosmetic – enhancing your appearance – and part pharmaceutical – giving you a desired result at the cellular level. I started to think, wouldn’t it be great if I approached the cosmetic market using pharmacognosy principles. For example, making sure that we were certain what extracts we were putting into our products, checking the quality of ingredients, making sure that we had pharmacy grade extracts and that there was no adulteration in our extracts. It’s quite common for plant extracts to be adulterated with cheaper alternatives. For example, chamomile is often adulterated with feverfew. To the naked eye, the plant and flower looks the same, but they have a whole different pharmacology. I heard once of a parsnip being used in traditional Chinese medicine as ginseng! It had been sprayed with ginseng, so tested positive, but was totally the wrong species.

So Dr. Jackson’s was born in 2008. I wasn’t quite sure if consumers were ready for this type of product, but I was wrong and it became very popular. For me it was more about keeping alive the discipline of pharmacognosy, and so we had mentions of the discipline in Vogue, GQ, Tatler and many other widely-read publications. It was quite something to bring this specialised area of study into the mainstream media. I think the beauty industry had been exposed to many ‘kitchen sink’ cosmeticians, who had started their businesses literally on the kitchen table. They were happy to find the real deal, a company founded on science and evidence-based research. I’d like to think we really forged the way for what can only now be described as the golden age of natural cosmetic products. We were very lucky for the opportunity to showcase African ingredients in our products. It really was about being at the right place at the right time for the company. Now African botanical ingredients are found in many cosmetic companies’ ingredient lists.

My husband John joined the company as the Business Development Manager, and we explored many export markets. Of course, the Asian markets really understood us as it’s very much ‘you are what you eat’ in Asia, and obviously traditional Chinese medicine has been around for over 2000 years, as has Ayurvedic medicine in India, so it was a lot easier to enter the markets there. In 2016 we had an opportunity to successfully exit the brand and then we moved to Ireland, to West Cork.

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Simon and John on a field trip to Zimbabwe

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

Steam distillation in the field in Zambezi

Can you explain the processes you had to go through to develop cosmetic products that you knew would work and the gap in the market you identified that they would fill ?

I had been thinking about making a skin cream using African products right back in 1993, when I first started seeing the health benefits of African ingredients, but it took me till 2008, when I set up my company, and then a further four years until I launched my first product in 2012. For me I was fed up with seeing all these other ‘natural’ brands launching products, but not really being natural at all. They are what we call ‘naturally inspired’ and made claim after claim, but with no real scientific knowledge being used. ‘Angel dusting’ is a term used in the industry where twenty to thirty ingredients are used in products to give it a therapeutic effect, when in reality you should never use more than 5 or 6 ingredients in a product. Less is definitely more in this case. For me the process was to identify the problem first and then work on a solution.

We have had lots of lovely testimonials from people using our products. For example, I’ve made a few oil products containing arnica and calendula, which are great for cosmetic use, but many patients with dry or thin skin after chemotherapy have said it’s the only thing that they can use on their skin. I wanted to make products that could be used by people with the most sensitive of skin conditions, especially with a lower immune system or people who wanted ‘chemical free’ products. For me the ‘gap in the market’ was offering post-chemical era natural products that actually work and contain active ingredients that are genuinely efficacious and replicable in every bottle.

I always made sure that we only made our products in GMP facilities, (Good Manufacturing Practice). We also make sure that all outsourced companies are ISO quality certified. It was very important for me to make sure that all our products were cruelty-free certified with absolutely no animal testing and were both vegetarian and vegan certified. It’s amazing how many companies make these claims, but don’t have the certification to back it up. One key thing that we do every time we develop any products is to thoroughly research any proposed ingredients. It’s all well and good introducing new species to people, but if that species is on the CITES list of endangered species then we will not take it to market.

For every ingredient we use, we have a whole process where we check the marketability of that species, whether research has been undertaken before, whether it is a commonly known ingredient, or whether it needs more research undertaken to be able to use it. Something that has been used traditionally in Africa may be seen as an exotic or novel foodstuff in Europe. So all of these considerations need to be taken into account. I guess people don’t see the amount of work that needs to be undertaken even before we set foot into the laboratory.

Since you and John moved to southern Ireland two years ago, you have been working together on a range of cosmetic products for your new venture, Modern Botany. What was the impetus behind this move and how do you find working together?

We moved here in 2016 to a little town called Schull on the beautiful wild Atlantic Coast in West Cork. It’s the most south-westerly point in Europe with the most spectacular unspoilt land and seascapes. It really is ‘Next stop America!’. John and I have been coming here regularly on our vacations and John’s family home is nearby, so we have a spiritual connection with the place and people, who are so friendly and hospitable. It has been a dream of ours to settle here and build a natural product company focusing on accessible, efficacious unisex personal care products. We are all about ‘clean and green’ beauty, so being such a clean and green environment as the West of Ireland is the perfect fit. West Cork was very much by-passed by the industrial revolution, so it is very unpolluted.

Working as a couple has its obvious challenges, but we have learned over the years to understand each other’s strong points and attributes. John is best at business development and managing relationships, while I focus on the science element of the business and innovative product development. I like to think that we complement each other in a way that’s conducive to our mutual goals. And we both love living in such a beautiful part of the world. We are even taking up a bit of kayaking and sailing, as we are so close the sea here. It’s also been great to learn more about marine pharmacognosy and local seaweed, so watch this space.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

A field of German chamomile at Simon and John’s farm in Schull

Can you describe the ethos behind the products you are developing for Modern Botany ?

We are very excited about our latest venture. We aim to elevate the quality and standard of personal care natural products by producing 100% natural and effective, frequent-use products. Our focus here is on personal care rather than beauty/cosmetic products and we want to highlight the importance of skin health. All our products are safe and designed for people with sensitive skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis or for pregnant mums. They are all chemical free with no parabens, petrochemicals or aluminium. We aim to educate consumers on awareness of what we put on our skin and all our products utilise the best from the natural world by creating formulations that are novel and innovative using natural ingredients that are of pharmaceutical grade extracts. This ensures the optimum therapeutic effect on your skin.

We are all about inclusivity and making easy-to-use and understandable products that are affordable and multi-purpose. We are an eco-sustainable company and all our packaging is recyclable and made in Ireland so that we can control our carbon footprint. Our aspiration is to eventually grow and process and introduce into our supply chain all of our constituent medicinal ingredients. We have been working with the agricultural department in Ireland and have these past two years been growing test crops with great results on our little farm. We want to encourage local farmers to grow flaxseed, chamomile, evening primrose, calendula and borage to start with, as all of them grow really well in the soil in our part of Ireland.

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Locally grown borage, chamomile, calendula and evening primrose being used in Modern Botany products

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018

Modern Botany Deodorant & Multi-tasking Oil

Are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with at the moment and why ?

We are working with some interesting plant species local to West Cork that have interesting medicinal properties. For instance, we are testing wild greater plantain (Plantago major) and bog cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium), both of which have traditional Celtic uses and can be used as astringents. We’re also looking at innovative methods of extraction from seaweeds such as serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) as well as Irish sphagnum moss, which both have incredible skin healing properties due to their anti-bacterial, wound-healing and moisturising capabilities and so are perfect for people with hypersensitive skin conditions.

How do you go about inventing and developing a new product and what’s on the cards for next year?

My starting point and our company ethos is to only create products that consider first and foremost what customers need. I’m not interested in just churning out the normal cosmetic range because it is marketable and commercially attractive. The process of development is more often exciting and inspiring when it’s making something where the genesis evolves from a genuine need and is also something that I myself would want to use.

For example, after we brought out our first product, I was approached by many people asking me to formulate a natural deodorant that was aluminium-free, but that also had to be an effective anti-perspirant. There are lots of natural deodorants on the market, but few that really work as an anti-perspirant. And that’s how Modern Botany Deodorant was developed, a multi-tasking product that is a deodorant, anti-perspirant and body scent. We have an exciting range of innovative 100% natural and unisex products coming on line in 2019, which include a universal wash that can be used by all the family, more varieties of deodorants, a multi-tasking healing emulsion and travel sets.

Interview: Huw Morgan/Photographs: Courtesy Simon Jackson and Modern Botany

Published 24 November 2018 When I was a child we spent every summer holiday in Wales, staying with my maternal grandparents who lived near Gowerton, the gateway to the Gower peninsula. When the weather was good we would head straight to Horton beach after breakfast, with crab paste and ham sandwiches wrapped in foil, hard-boiled eggs, bags of crisps and a tin of Nana’s homemade Welsh Cakes and pre-buttered slices of Bara Brith to see us through the day.

My grandfather was a Baptist minister, so on Sundays the day started differently. Nana was up even earlier than usual, housecoat on and getting lunch (or dinner as we called it in those days) prepared before we all headed off to chapel. All of the vegetables came from the back garden, which was given over entirely to food; potatoes, runner beans, peas, broad beans, lettuces, onions, beetroot, carrots, parsnips, swedes, cabbages and, of course, leeks. A tiny greenhouse was full to bursting with tomatoes and cucumbers. At the front of the house, the long bed running down one side of the path was filled with Dadcu’s dahlias, tied to bamboo canes in regimented rows, a cacophony of colour in every shape available, like sweeties. On the other side of the path an assortment of exotics planted into the lawn, including a phormium, a bamboo and a pampas grass, provided me and my brother with a playtime jungle.

The chapel was just on the other side of the street so, as soon as the service was over, Nana would head back to the manse to get dinner on the table for Dadcu’s return. Although a full roast dinner was not unusual on these sweltering summer Sundays, the meal I remember most clearly, and which was my favourite, was cold boiled ham with minted new potatoes and broad beans in parsley sauce. I loved the combination of the cold, salty meat, buttery potatoes and creamy beans and would ensure I got a little of each on every forkful.

Thinking back to this garden now I realise that, although Dad also grew veg in our North London garden, it was Dadcu’s kitchen garden where I first really understood the connection between plant and plate. My brother and I would be sent out to help dig potatoes, getting a rush of excitement as the first pearly tubers were heaved from the rich, dark soil, scrabbling to grab them and put them in the bucket. Pulling carrots straight from the ground I would think of Peter Rabbit, although I was sure that, unlike Mr. McGregor, the Revd. Jones did not have a gun. And often I would sit on the back step with Nana and Mum easing broad beans from their pods, marvelling at their cushioned, fleecy protection and enjoying the plonking noise they made as they fell into a plastic bowl at our feet. I never questioned that what we ate at mealtimes had been grown just yards from the dining table, nor that there was work required to get it there. I think that even then those vegetables tasted better to me because they were so fresh and I had helped get them to table.

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Broad Bean ‘Karmazyn’

Although I can’t profess to be as good a vegetable gardener as my grandfather, now that we have a kitchen garden of our own, I find it hard to buy anything other than lemons, melons or peaches from the local greengrocer in the summer. The feeling of being able to assemble a meal entirely from vegetables you have grown, harvested and prepared yourself has no equal. People say that vegetable gardening is hard work, and I agree, but I don’t understand why this is seen as a negative. The time, care and nurturing that goes into producing your own food gives you a connection to it that is as nourishing as the food itself. When you understand the hard work involved in growing, tending and harvesting you stop taking food for granted and get some perspective on how much food should really cost.

So, to get back to the broad beans. We have grown two varieties this year. An unnamed heritage variety with very decorative, dark pink flowers and green beans from a late autumn sowing, and a variety named ‘Karmazyn’, with white flowers and beautiful rose pink beans, which were sown in March. Surprisingly, the later sown ‘Karmazyn’ have been the quicker to mature. Earlier in the season, as it became apparent that the plants were starting to overtake their autumn-sown neighbours, I was concerned that we were going to have a major glut when both varieties came together, but it now appears we will have a good succession from pink to the green. Close by the artichokes are producing almost faster than we can eat them. ‘Bere’, the variety we grow, is spiny with little meat at the base of the leaves, but the hearts are a good size, sweet and strongly flavoured.

Due to their synchronised production in the garden it is no surprise that broad beans and artichokes are commonly cooked together, with a variety of recipes to be found in French, Italian, Greek, Turkish and other Middle Eastern cuisines. What is common to many of them is the generous use of lemon and fresh herbs. This recipe is very loosely based on an Elizabeth David recipe for Broad Beans with Egg & Lemon from Summer Cooking, which would appear to be of Greek origin. Here the boiled vegetables are dressed with a light, creamy, herb-flecked sauce. A more refined and delicate version of my dear Nana’s beans, although just as good with a couple of slices of cold, boiled ham.

Artichoke ‘Bere’

Artichoke ‘Bere’

INGREDIENTS

Artichokes, 4 small per person

Broad beans, I kg in their pods to yield about 250g

Zest and juice of 1 lemon (reserve 1 tablespoon of juice for the sauce)

Sauce

Butter, 25g

Garlic, a small clove, minced

Cornflour, 1 teaspoon

The yolk of a small egg, beaten

Single cream, 4 tablespoons

Tarragon or white wine vinegar, 1 teaspoon

Lemon juice, 1 tablespoon

Cooking water from the beans, about 200 ml

Fennel, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Dill, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Tarragon, 1 tablespoon finely chopped

Salt

Serves 4

METHOD

Bring a large pan of water to the boil. Cook the artichokes for 15-20 minutes until the point of a sharp knife can be easily inserted into the base. Drain the artichokes, run under a cold tap for a moment and then allow to drain and cool completely.

Put the lemon juice in a small bowl. Cut the stalks from the artichokes and gently remove and discard all of the leaves until you reach the choke. Carefully scrape out the choke with the edge of a teaspoon. Tidy the hearts with a sharp knife removing any tough green bits. Rinse in a bowl of water to remove any clinging choke hairs. Dip each heart into the lemon juice as you go and put to one side in a bowl.

Bring a fresh pan of water to the boil. Throw in the beans and cook until just done. Freshly picked ones take only 2 or 3 minutes, older beans will take a little longer and may need to be slipped from their tough outer skins after cooling. When cooked remove 200ml of the cooking water and keep to one side. Then drain the beans and immediately refresh in cold water. Drain and reserve.

To make the sauce, in a pan large enough to take the artichokes and beans, melt the knob of butter until foaming. Take off the heat, put in the garlic and swirl the pan around to cook it lightly and flavour the butter. Still off the heat put in the cornflour and stir well. Add the cream and stir again. Add the egg yolk and stir once more. Then add about 150ml of the reserved cooking water, the vinegar and lemon juice. Season with salt. Put the pan back on a low heat and stir continuously until the sauce starts to thicken. Taste to ensure the cornflour is well cooked and adjust the seasoning. The sauce should be glossy and the consistency of single cream. If it is too thick loosen with some of the reserved cooking water. Put in the chopped herbs and lemon zest and stir through. Put the artichokes and broad beans into the pan and stir gently but thoroughly to ensure that all of the vegetables are well coated with the sauce.

Transfer to a serving dish, and strew some more herbs and lemon zest over the top. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Good enough to eat simply on its own or on toast, this is also a perfect side dish for poached salmon or trout, and cold roast chicken.

You can use any combination of soft green herbs that you have available. Chervil is particularly good, as are parsley and mint. For a more substantial side dish a couple of handfuls of the tiniest, boiled new potatoes make a fine addition.

Recipe & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 June 2018

Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my earliest inspiration were the roses growing on the pathway leading up to our childhood house. That scent has stayed with me forever. The rose is a very powerful plant, it triggers so many memories. Like a form of time travel, it has taken me to some very magical times and places, it has been hugely influential.

Then I was inspired by learning about distilling plants with an eau de vie distiller in Alsace and connecting with herbalists such as Peter Jackson Main, Peter Conway, the work of Barbara Griggs and for sure the writing of Stephen Harrod Buhner. I urge everyone to read his book The Lost Language of Plants.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Photo: Susan Bell

You are a qualified Phytotherapist. Can you explain what that means and what the training involves?

It’s a posh term for a herbalist, to make us sound more professional. It means somebody who works with plants to heal and nurture people. We introduce nature and look at ways in which plants can help support disease, illness or just enrich people’s lives.

I trained with many naturopaths, nutritionists, herbalists and plant workers on shorter courses and then went into a full time BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Westminster. It took four years of full time training, but some of the most valuable training is spending time with the plants themselves. They can teach you a great deal.

Tell us about the range of products you produce, and the process you went through to develop them.

It all started as I was unhappy with the quality of the herbs & spices in many herbal teas and commercial spice ranges. There was (is) a distinct lack of relationship between people and the plants that they are drinking or eating. Supermarkets are littered with herbs in tea bags and boxes, but you don’t see the plants or engage with them enough. You don’t know where they are from, when they were harvested, who harvested them, you can’t even see the plants. So I wanted to create a range of plant products where you could really engage with the plant itself, on a very basic level by looking at and identifying it, drinking its qualities. It’s about engaging with and respecting nature really. I want people to see the love and hard work (from both the plant and the people producing them) that goes into nurturing, growing, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs.

We take plants for granted most of the time. Just take black pepper for example. In almost all households it is just a commodity. It’s just not celebrated enough. It’s a sensational plant, with brilliant flavour. Just take a good quality black peppercorn and place it in your mouth and eat it. Taste it fully and consider its qualities. Phenomenal.

We really want people to engage with the nature that they are drinking, eating and ingesting. All of our plants are harvested in that growing year, we know when they were harvested and by whom. We make our infusions, waters and bitters in tiny batches. It’s all created by hand with lots of care using the most vibrant plant material possible.

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

Our aromatic waters (non-alcoholic distillations of plants) were sourced from two distillers in the UK and India, although we have since stopped working with them as we are now distilling everything ourselves. There will be some very special distillates available in 2018 as we are currently working on polypharmic distillations, distilling lots of different plants at the same time. There is a natural synergy between plants in the wild and it’s always interesting to see which plants like to grow together, for example nettle & cleavers. We are trying to capture this synergy and relationship in the form of a distillation.

We distil plants in traditional copper alembic stills (main image – photo by Susan Bell) to use as a flavouring for food and drinks and as ingredients for natural skin care. We are just starting to use CO² extraction, which produces the most beautiful and vibrant oils. We also work with co-operatives in Southern India and Sri Lanka who supply us with beautiful vibrant spices. Again it is crucial that we know who harvested the plants, where and when. We visit the growers on their tiny holdings – when I say tiny they are really tiny, 1 hectare and less – and they cannot afford organic certification, so that’s where the co-operative comes in, to help give the growers the sales platform and access to people like us.

The bitters are remedies and recipes that I had been using in practice and for drinks creation for years. They cover all of my inspirations, so there is an English-based blend with 20 herbs grown here, an Indian blend with spices like cinnamon, turmeric and one of my favourite bitter herbs, Andrographis, and a Chinese blend with Chinese herbs such as Schisandra paired with a beautiful rock oolong tea from our dear friends at Postcard Teas. We wanted to share these formulas with everyone.

From where and how do you source your ingredients?

The herbs we use are mostly grown, nurtured, harvested and dried by a wonderful grower called Diane Anderson who has a smallholding in Oxted, Surrey. Diane was one of my teachers at University. She was an amazing resource and she used to come into the dispensary with the most beautiful dried herbs. Seeing these wonderful dried herbs was also an inspiration to start blending infusions.

We also work with a biodynamic plantation in Somerset, we grow a few things ourselves and for the more exotic plants, as mentioned before, we source from our friends in Southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cardamom

Cardamom

Turmeric

Turmeric

Can you explain how the bitters and herbal waters you produce might be used?

I’m not allowed to talk too much about the health benefits of our products, so broadly speaking their purpose is really to enhance and envigorate drinks and dishes and to give pleasure. The bitters are amazing just with water, or fresh juice, pre- and post-prandial, to stimulate digestive function and assimilate some of the metabolites from your meal. The aromatic waters are so diverse, I use them every day in a glass of water, sprayed directly on my face as a toner (rose), in salad dressings (rosemary & thyme are particularly good), to create cocktails with and without alcohol. They are amazing.

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

Can you tell us something of the therapeutic effects of some of your key ingredients?

Plants have endless therapeutic qualities on so many levels, physically, spiritually, emotionally, and I think it’s important that you are ingesting some good quality organic plants every day. I don’t want to say as part of a routine as that sounds boring, but use them prophylactically as a preventative. Have fun with plants, get to know them, enjoy their nature, enjoy their brilliance, it’s so rewarding for health and happiness.

The herbs we use and work with are packed full of complex secondary metabolites, diverse plant chemicals (phytochemicals) produced by the plants which enable the plants to interact with their environment. These phytochemicals have a wide range of functions, including protection from herbivores, to fight against infections and to attract pollinators such as bees and other insects. The plant’s secondary metabolites include constituents such as tannins, aromatic oils, alkaloids, resins and steroids. It is these chemicals that not only carry a raft of potential health benefits for us, but also offer a huge palette of flavours, textures and aromas to create delicious food and drinks.

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

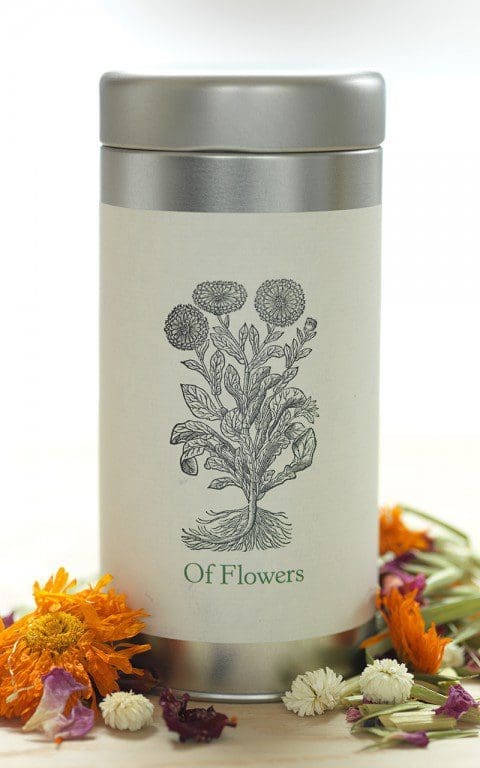

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

You have a book coming out in the new year. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Super exciting, yes. It’s a book on my work really. I talk about my inspirations, some of the plants that I work with, when and how to harvest them and then how you can work with those plants to create dynamic and delicious botanical drinks. I talk about distillation, extraction methods, drying and processing the plants and then there are over fifty recipes, all without alcohol.

Would you share a recipe with us that readers can try at home?

Sure. I’m drinking a lot of sage right now so here is a simple recipe with sage including a quote from John Gerard, whose work we have been greatly inspired by, he wrote (or collated and published) the seminal text The Herball or Generall historie of plantes, 1597.

THE WISE ONE

‘Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members’. John Gerard 1545 – 1612.

Photo: Susan Bell

Photo: Susan Bell

This is a contemporary take on a classic sage preparation to produce a cooling, blood cleansing formula, which makes for a sensational afternoon tipple.

Plants & Ingredients

Sage Salvia officinalis

Lemon Citrus limon

Sugar Saccharum officinarum

Water

Recipe

15g fresh sage

4 lemons

500ml hot water

75ml lemon & sage sherbet (see below)

100g sugar

Method

Boil the water, then pour over 10g of sage into a pot with a lid. Infuse with the lid on for 30 minutes before straining into another jug or decanter. Peel 1 of the lemons and keep the zest. Add the juice of that lemon and the sherbet to the decanter and stir until dissolved. Keep the jug or decanter in the fridge to chill and serve once cold.

Serve in a wine glass with the remaining twist of lemon and fresh sage leaves

For the Sherbet

Peel the remaining 3 lemons, then put the zests in a container with the sugar and the remaining 5g of sage. Press the zests with the sugar and sage for a minute or so, then juice the lemons and stir the juice into the sugar mixture. Seal and leave to infuse overnight, or for at least 6 hours. Stir, strain and bottle. This will keep refrigerated for at least 1 month and can be enjoyed with still and sparkling water.

The Herball’s Guide to Botanical Drinks: A Compendium of plant-based potions to Energise, Cleanse, Restore, Boost Sleep and Lift the Heart by Michael Isted, photography by Susan Bell, will be published by Jacqui Small in February 2018. Pre-order here.

Twitter: @TheHerball

Instagram: theherball

Interview: Huw Morgan/All other photographs: Laura Knox

Published 30 September 2017

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage