There is a point when winter turns and spring takes over. It inches at first, and then that false feeling – that you have time on your hands – begins to evaporate. This year I have been watching for the change more intently than usual, because we had a date in the diary to plant up the first phase of the new garden; the week of the spring equinox which, this year, proved to be perfect timing. One week later and the peonies were already a foot high and the tight fans of leaf on the hemerocallis were flushed and beyond moving without setting them back.

I have been planning for this moment for three years, perhaps longer in refining the idea of the way I wanted the planting to nestle the buildings and blend with the land beyond. I procrastinated over the final plant list for as long as it was possible, but in January it finally went out to the nurseries in time to get the stock I needed for spring.

The process of refining a plant palette is one that I know well, but committing a plan to paper is an altogether more difficult thing to do for yourself than for a client. I decided not to make an annotated plan, but instead to map a series of areas that shift in mood as you walk the paths. I paced the space again and again to understand where the ground was most exposed, where it was free-draining and to note that, in the hollow where the ground swung down to the track, there was running water a spit deep this winter. I imagined where I would want height and where I would need the planting to dip, sometimes deep into the beds, to give things breathing space. There would also need to be countermovements across the site, with tall emergent plants brought to the foreground, close to the paths.

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The final stages of soil preparation in early March

The preparation was completed the week before the plants arrived; the soil dug in the windows when it was dry enough and then knocked out level just in time. We prayed that the weather would dry up, because the soil had lain wet all winter and would not stand footfall if it stayed that way. In tandem with the soil preparation we moved some favourites that I have been bulking up, like the Paeonia mlokosewitschii and Paeonia emodii ‘Late Windflower’, both of which came with us from Peckham, and split those plants that had passed the test in the trial garden. A three year old Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ was easily divided into eight, and so three plants gave me twenty four to play with; enough to move from bed to bed and to jump the path. The same with the persicarias, the Iris x robusta ‘Dark Aura’, the Aster turbinellus and a long list of others. These were bagged up individually so that I could afford to leave them laid out when shifting the planting around on the day of laying out.

Due to the size of the site this was just the first round of planting, and of only half the garden. The remaining half will be planted this autumn. The plan for this lower half comprises a dozen interlocking areas, which allow my combinations to vary subtly across the site and flow into one another to form a related whole. Before starting, the boundaries were sprayed onto the soil with a landscape marker, although I break these boundaries during setting out, jumping plants across to knit them together.

Shrubs and woody plants were positioned first to articulate the space. Trees by the gates including Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Barmstedt Gold’ and Crataegus coccinea, some Malus transitoria and Rosa glauca breaking in from high up, and home-grown whips of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Salix gracilistyla fraying the edges alongside the field. Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’, the largest of the clump forming grasses, was also given its position early to tie the meeting point of the paths together.

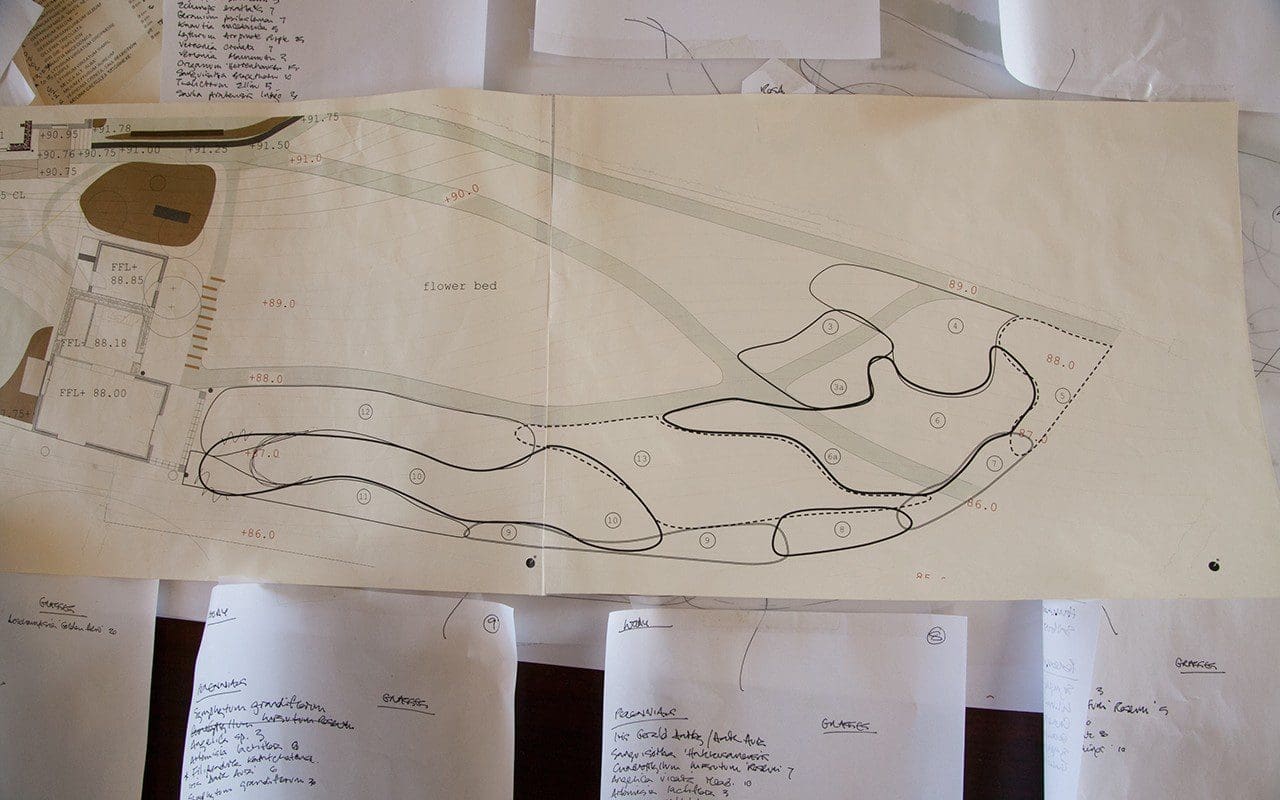

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

Plan showing the twelve interlocking planting zones

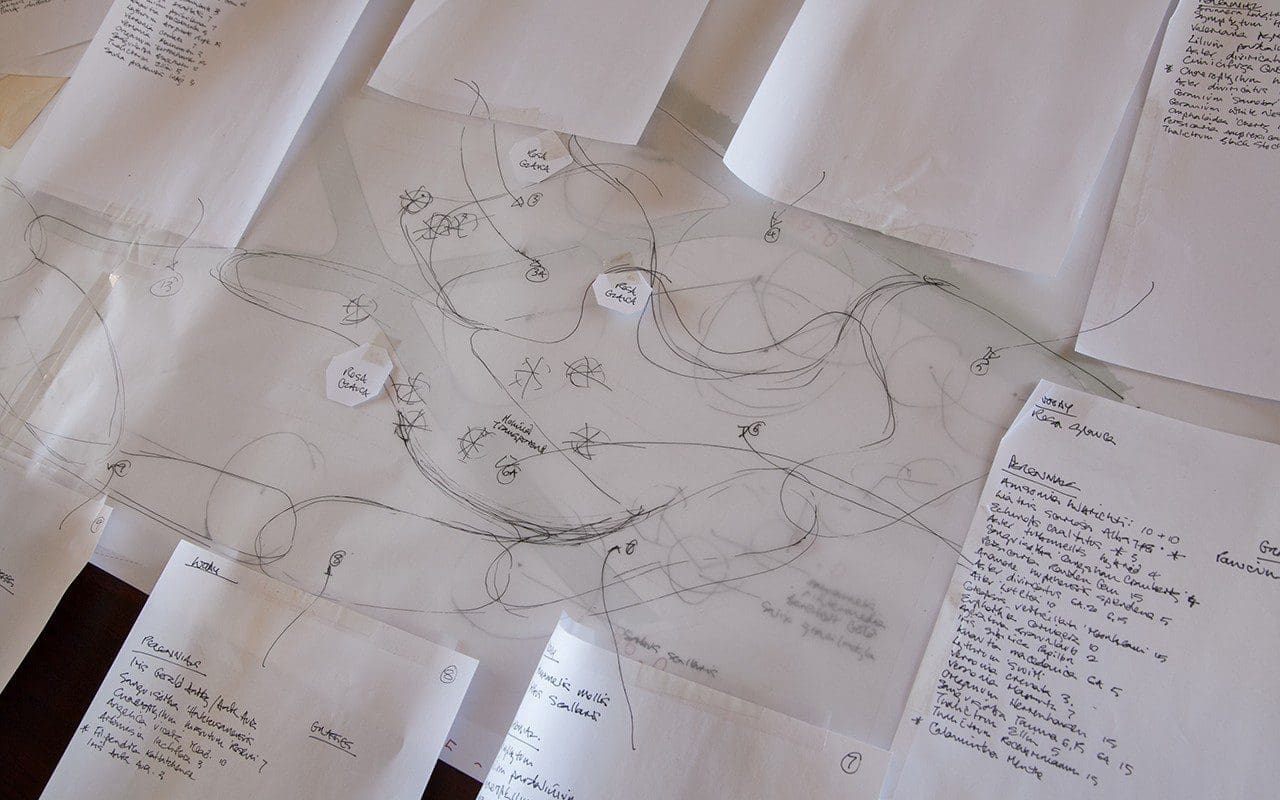

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

Dan’s hand-drawn zoning plan with developing plant lists

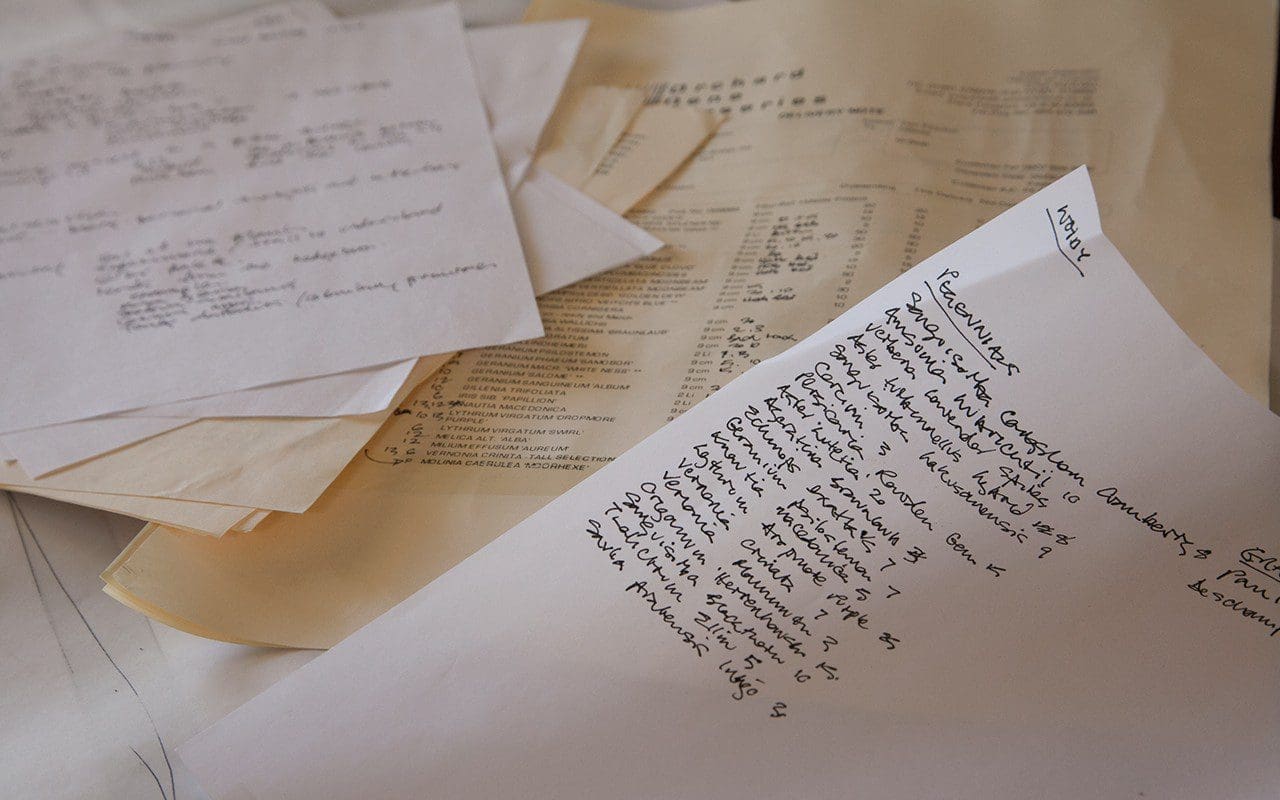

Plant lists and orders

Plant lists and orders

For each of the zones I made a list that quantified all of the plants I would need to make it special. A handful of emergents to rise up tall above the rest; Thalictrum ‘Elin’, Vernonia crinata, sanguisorbas and perpetual angelicas. When laying out these were the first perennials placed to articulate the spaces between the shrubs and key grasses.

Next, the mid-layer beneath them, with the verticals of Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Rowden Gem’, and the mounding forms of aster (A. divaricatus) or geranium (G. phaeum ‘Samobor’, G. psilostemon and G. ‘Salome’). The plants that will group and contrast. And finally, the layer beneath and between, to flood the gaps and bring it all together. These were a freeform mix; fine Panicum ‘Rehbraun’ with Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Tanna’, or Viola cornuta ‘Alba’, Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ and the white bloody cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum ‘Album’.

The plants arrived from Orchard Dene Nurseries and Arvensis Perennials on the Friday. Immaculate and ready to go and filling up the drive. I like to plant small with nine centimetre pots. If you get the timing right, and don’t have to leave them sitting around, this size is easily trowelled in with minimum soil disturbance. At close spacing this makes planting easier and faster than having to spade in a larger plant.

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants waiting to be put in position along the paths

Plants grouped by planting zone

Plants grouped by planting zone

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

Colour-coded sticks were used to mark the positions of plants yet to be supplied

It took us two days to complete the lifting and dividing of my stock plants and to set the plants on the paths in their groups. And the process was prolonged as I started adding last minute choices from the stock beds. On the Sunday high winds whistled through the valley to dry the soil, so I started setting out and hoped that the pots didn’t blow into one corner overnight, as once happened in a client’s garden. On the Monday, and ahead of my team of planters who were arriving the next day, I continued to populate the spaces, between the heavens opening up and pouring stair-rods. It was hard, and there was a moment I despaired of us being able to get the plants in the ground at all.

Setting out plants is one of the most all-consuming and taxing activities I know. It feels like it uses every available bit of brain-space. You not only have to retain and visualise the various volumes, cultural requirements and habits of the individual plants, but also the sequencing and rhythm of a planting, how it rises and falls, ebbs and flows, and then how each area of planting relates to the next, in three dimensions and from all angles. Add to this the aesthetic considerations of colour relationships both within and between areas and the time-travel exercise of imagining seasonal changes and there is only so much I can do in one session. However, I was ahead of my planters and, as long as I could hold my concentration once they arrived, it would stay that way with them coming up behind me. The rains abated, the wind continued and the following day the soil was dry enough for planting.

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Dan concentrating on plant layout

Jacky Mills

Jacky Mills

Ian Mannall

Ian Mannall

Ray Pemberton

Ray Pemberton

On the 21st, the sun broke through not long after it was up. A solitary stag silhouetted against the sky looked down on us from the Tump as we readied for the day. Clearly word had already got out that there were going to be rich new pickings in the valley.

Over the course of two days about twelve hundred plants went in the ground. Three people planting and myself managing to stay ahead, moving the plants into position in front of them. Thank you Ian, Jacky and Ray for your hard work, and Huw for supplying a constant supply of necessary vittles.

I cannot tell you – or perhaps I can to those who know this feeling too – what a huge sense of excitement is wrapped up in a new planting. Plans and imaginings, old plants in new combinations, new plants to shift the balance. All that potential. All those as yet unknown surprises.

Already, the space is changed. We will watch and wait and report back.

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

6 April 2017, two weeks after planting

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Winter is a productive season here in Britain. The weather rarely closes in to stop us for more than a few days and, with the garden in stasis, there is room to think and plan and do. The few truly dormant weeks saw us clearing another fallen tree in January, logging the wood for the winter and stacking the brush into piles (main image) that will become home to the creatures, lichens and fungi that like the protection and decay. If we have snow the tracks to and from the stacks advertise their occupancy but, where the surrounding grass gives way to the shelter within, there are already signs of the annual cleavers that climb into their cages and clothe them in summer. Before the hedges were cut we harvested a few bundles of hazel to provide twiggy support for broad beans and sturdy poles for the sweet peas and climbing beans. They are a welcome bounty and the result of cutting the hedges every other year to allow them time to flower and berry. Two years is just enough time for the oldest and strongest hazel in the hedge to push out a good length of twiggery. Next year, whilst the hedges are growing back, I will coppice a couple of our freestanding hazel. It is hugely gratifying to be self-sufficient for plant supports for the garden. Whilst they are regenerating the hazel stumps are protected from the nibbling of deer with woven cages of offcuts. A coppiced hazel protected from deer by a cage of offcuts

A coppiced hazel protected from deer by a cage of offcuts

Hazel poles harvested from the hedgerows

Though we complain here about the winter’s duration, I cannot help but compare these few fairly benign months to the harsh conditions at my project in Hokkaido. There the gardeners have to leave the frozen landscape in search of work whilst the garden lies beneath deep snow until late April. The rush of tasks to either side – in preparation for the slumber and then the great surge of activity in spring – is palpable in head gardener Midori’s communications. Meanwhile, here we are free to dig and prune and plant. What luxury it is to get things in order with these few weeks of down time on our hands.

Hazel poles harvested from the hedgerows

Though we complain here about the winter’s duration, I cannot help but compare these few fairly benign months to the harsh conditions at my project in Hokkaido. There the gardeners have to leave the frozen landscape in search of work whilst the garden lies beneath deep snow until late April. The rush of tasks to either side – in preparation for the slumber and then the great surge of activity in spring – is palpable in head gardener Midori’s communications. Meanwhile, here we are free to dig and prune and plant. What luxury it is to get things in order with these few weeks of down time on our hands.

The Meadow Garden at the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido is under snow until late April. Photograph: Syogo Oizumi

It has been a busy winter for I am readying myself to plant up the first sections of the new garden that was landscaped last summer. This time last year the same ground lay fallow with a green manure crop protecting it from the leaching effect of rain and to keep it ‘clean’ from the cold season weeds that colonise whenever there is a window of growing opportunity. The winter rye grew thick and lush, except where the diggers had tracked over the ground during the previous summer’s building works, where it grew sickly and thinly, indicating that something needed addressing before going any further.

When we started the winter dig, the problem that the rye had mapped became clear. Not far beneath the surface the soil had become anaerobic, starved of air by the compaction and with the tell-tale foetid smell as you turned it. The organic matter in the soil had turned grey where the bacteria were unable to function without oxygen and the water ran off and not through as it should. Turned roughly at the front end of winter, like a ploughed field, the frost has since teased and broken this layer down and the air has made its way back into the topsoil to keep it alive and functioning. Though it is still too wet to walk across, you can see that the winter freeze and thaw has worked its magic and that, as soon as we have a dry spell, it will knock out nicely like a good crumble mix, in readiness for planting.

The Meadow Garden at the Tokachi Millennium Forest in Hokkaido is under snow until late April. Photograph: Syogo Oizumi

It has been a busy winter for I am readying myself to plant up the first sections of the new garden that was landscaped last summer. This time last year the same ground lay fallow with a green manure crop protecting it from the leaching effect of rain and to keep it ‘clean’ from the cold season weeds that colonise whenever there is a window of growing opportunity. The winter rye grew thick and lush, except where the diggers had tracked over the ground during the previous summer’s building works, where it grew sickly and thinly, indicating that something needed addressing before going any further.

When we started the winter dig, the problem that the rye had mapped became clear. Not far beneath the surface the soil had become anaerobic, starved of air by the compaction and with the tell-tale foetid smell as you turned it. The organic matter in the soil had turned grey where the bacteria were unable to function without oxygen and the water ran off and not through as it should. Turned roughly at the front end of winter, like a ploughed field, the frost has since teased and broken this layer down and the air has made its way back into the topsoil to keep it alive and functioning. Though it is still too wet to walk across, you can see that the winter freeze and thaw has worked its magic and that, as soon as we have a dry spell, it will knock out nicely like a good crumble mix, in readiness for planting.

Digging over the compacted soil, working from boards to prevent further compaction

Time taken in preparation is never time wasted and it is a good feeling to give new plants the best possible start in their new positions. As the soil was previously pasture and we have the advantage of heartiness, the organic content is already good enough, so we will not be digging in compost this year. I want the plants to grow lean and strong so that they can cope with the openness and exposure of the site rather than be overly cosseted or encouraged to grow too fast and fleshy. Organic matter will slowly be introduced after planting in the form of a weed-free compost mulch to keep the germinating weeds down and to protect the soil from desiccation. The earthworms, which are now free to travel through the previously compacted ground, will pull the mulch into the soil and do the work for me.

Digging over the compacted soil, working from boards to prevent further compaction

Time taken in preparation is never time wasted and it is a good feeling to give new plants the best possible start in their new positions. As the soil was previously pasture and we have the advantage of heartiness, the organic content is already good enough, so we will not be digging in compost this year. I want the plants to grow lean and strong so that they can cope with the openness and exposure of the site rather than be overly cosseted or encouraged to grow too fast and fleshy. Organic matter will slowly be introduced after planting in the form of a weed-free compost mulch to keep the germinating weeds down and to protect the soil from desiccation. The earthworms, which are now free to travel through the previously compacted ground, will pull the mulch into the soil and do the work for me.

One of the planting beds in the new garden half dug over to allow the frost to do its work

In the vegetable beds, where we have been working the soil and demanding more from it, the organic matter is replenished annually to keep the fertility levels up. Our own home made compost is dug in now that the heaps are up and running. The compost is left a whole year to break down so that one bay is quietly rotting whilst the other is being filled. If I had more time, or a forklift to turn it, I would have a better, more friable compost in just six months. Turning allows air into the heap and the uncomposted material moved to the centre heats the heap more efficiently to help to kill weed seeds.

One of the planting beds in the new garden half dug over to allow the frost to do its work

In the vegetable beds, where we have been working the soil and demanding more from it, the organic matter is replenished annually to keep the fertility levels up. Our own home made compost is dug in now that the heaps are up and running. The compost is left a whole year to break down so that one bay is quietly rotting whilst the other is being filled. If I had more time, or a forklift to turn it, I would have a better, more friable compost in just six months. Turning allows air into the heap and the uncomposted material moved to the centre heats the heap more efficiently to help to kill weed seeds.

One of the compost bays

My year old compost is only really good for turning in as it springs a fine crop of seedlings from the hay we rake off the banks in the summer. There are also rashes of garden plants; euphorbias that were thrown on the heap after their heads were cut in seed, bronze fennel, Shirley poppies, phacelia and a host of other plants that have lain dormant. No matter. Since the heaps sit directly on the earth the compost is full of worms, and this can only be good for the soil and its future aeration. You can see the soil in the garden getting better and darker, more friable and more retentive with every year that passes. A reward for the hard work and payback for the bounty that we take from it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

One of the compost bays

My year old compost is only really good for turning in as it springs a fine crop of seedlings from the hay we rake off the banks in the summer. There are also rashes of garden plants; euphorbias that were thrown on the heap after their heads were cut in seed, bronze fennel, Shirley poppies, phacelia and a host of other plants that have lain dormant. No matter. Since the heaps sit directly on the earth the compost is full of worms, and this can only be good for the soil and its future aeration. You can see the soil in the garden getting better and darker, more friable and more retentive with every year that passes. A reward for the hard work and payback for the bounty that we take from it.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan It has been an exciting autumn, and one that I have looked forward to and been planning towards for the past six years. It has taken this long to resolve the land around the house. First to feel the way of the place and then to be sure of the way it should be.

Though the buildings had charm, (and for five years we were happy to live amongst the swirly carpets and floral wallpapers of the last owner) the damp, the white PVC windows and the gradual dilapidation that comes from years of tacking things together, all meant that it was time for change. Last summer was spent living in a caravan up by the barns while the house was being renovated. We were sustained by the kitchen garden which had already been made, as it provided a ring-fenced sanctuary, a place to garden and a taste of the good life, whilst everything else was makeshift and dismantled.

This summer, alternating between swirling dust and boot-clinging mud, we made good the undoings of the previous year. Rubble piles from construction were re-used to make a new track to access the lower fields and the upheavals required to make this place work – landforming, changes in level, retaining walls and drainage, so much drainage – were smoothed to ease the place back into its setting.

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

Of course, it has not been easy. The steeply sloping land has meant that every move, even those made downhill, has been more effort and, after rain, the site was unworkable with machinery. We are fortunate that our exposed location means that wet soil dries out quickly and by August, after twelve weeks of digger work and detail, we had things as they should be. A new stock-proof fence – with gates to The Tump to the east, the sloping fields to the south and the orchard to the west – holds the grazing back. Within it, to the east of the house and on the site of the former trial garden, we have the beginnings of a new ornamental garden (main image). An appetising number of blank canvasses that run along a spine from east to west

The plateau of the kitchen garden to the west has been extended and between the troughs and the house is a place for a new herb garden. Sun-drenched and abutting the house, it is held by a wall at the back, which will bake for figs and cherries. The wall is breezeblock to maintain the agricultural aesthetic of the existing barns and, halfway along its length, I have poured a set of monumental steps in shuttered concrete. They needed to be big to balance the weight of the twin granite troughs and, from the top landing, you can now look down into the water and see the sky.

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

On the lower side of the new herb garden, continuing the bank that holds the kitchen garden, the landform sweeps down and into the field. Seeded at an optimum moment in early September, it has greened up already. Grasses were first to germinate, and there are early signs of plantain and other young cotyledons in the meadow mix that I am yet to identify. I have not been able to resist inserting a tiny number of the white form of Crocus tommasinianus on the brow of the bank in front of the house. There will be more to come next year as I hope to get them to seed down the slope where they will blink open in the early sunshine. I have also plugged the banks with trays of homegrown natives – field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and divisions of our native meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) – to speed up the process of colonisation so that these slopes are alive with life in the summer.

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Below the house, the landform divides to meet a little ha-ha that holds the renovated milking barn and a yard which will be its dedicated garden space. This barn is our new home studio and from where I am planning the new plantings. I have placed a third stone trough in this yard – aligned with those on the plateau above – with a solitary Prunus x yedoensis beside it for shade in the summer. There are pockets of soil for planting here but, beyond the two weeks the cherry has its moment of glory, I do not want your eye to stop. This is a place to look out and up and away.

That said, I have been busily emptying my holding ground of pot grown plants that have been waiting for a home, and some have gone in close to the milking barn to ground it; a Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ from the old garden in Peckham, a Paeonia rockii, a gift from Jane for my 50th, and the beginnings of their underplantings, including Bath asparagus and some favourite hellebores that I’ve had for twenty years or more. The spaces here are tiny and they will need to work hard so as not to compete with the view out, nor disappoint when you get up close on your way to the barn. The bank sweeps up to wrap the milking barn above and to the east and the planting with it, so that it is nestled in on both sides. Below the barn there is the contrast of open views out into the fields, so when inside I can keep a clear head from the window.

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

To help me see my new canvasses in the new ornamental garden clearly I have started dismantling the stock beds. The roses, which have been on trial for cutting, will be stripped out this winter and the best started again in a small cutting garden above the kitchen garden. I’ve also been moving the perennials that prefer relocation in the autumn. Jacky and Ian, who help in the garden, spent the best part of a day relocating the rhubarbs to the new herb garden. It is the third time I have moved them now (a typical number for most of my plants), but this will be the last. In our hearty soil, they have grown deep and strong and the excavations required to lift them left small craters.

The perennial peonies, which go into dormancy in October, also prefer an autumn move, as do the hellebores so that their roots are already established for an early start in the spring. They both had a firm grip and I had to lift them as close to the crowns as I dared so that they were manageable. The hellebores have been found a new home in a rare area of shade cast by a new medlar tree that I planted when the landscaping was being done. I rarely plant specimen trees, preferring to establish them from youngsters, but the indulgence of a handful, which included the cherry and a couple of Crataegus coccinea on the upper banks near the house, have helped immeasurably in grounding us in these early days. To enable a July planting these were all airpot grown specimens from Deepdale Trees which, as long as they are watered rigourously through the summer, establish extremely well. Usually right now is my preferred (and the ideal) time to plant anything woody.

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

It is such a good feeling to have been planting things I have raised from seed and cuttings for this very moment; a batch of seedlings grown on from my Malus transitoria to provide a little grove of shade in the new garden, rooted cuttings of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ to screen the new garden from the field below, and a strawberry grape (Vitis vinifera ‘Fragola’), a third generation cutting from the original given to me thirty years ago by Priscilla and Antonio Carluccio, is finally out of its pot and on the new breezeblock wall. Close to it I have a plant of the white fig (Ficus carica ‘White Marseilles’), a cutting from the tree at Lambeth Palace, where I am currently working on the landscaping around a new library and archive designed by Wright & Wright Architects. The cutting was brought from Rome by the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole, in 1556. In 2014 a cutting made the return journey to Pope Francis, a gift of the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. The tree reaches out from the palace wall in several directions to touch down a giant’s stride away. It is probably as big as our little house on the hill, and my cutting is full of promise. It is so very good, finally, to be making this start.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan, Dan Pearson & Jacky Mills

This is the third year of my aster trial and a good point to judge how they have performed. The collection, which I set up to broaden my palette, has scratched the very tip of an iceberg, which must run to hundreds of varieties. I currently have just twenty-six and I am at the point now of wanting to reduce them to a dozen or so. Some I have grown before, but the greater number have been selected from plant fairs and on trips to see the well-known collections at Waterperry Gardens and the Picton Garden.

Asters are some of the best late-flowering perennials, the first flowers to hint at the next season in late August, and some of the very last to see the autumn out, their flowers hanging in suspension as the colour drains from everything around them. Aster borders were once celebrated in Victorian and Edwardian gardens, but they became unpopular for a period and with good reason. Many of the older varieties were prone to mildew and those that run could take a border over in the same time that I have been running my trial. I suspect this is one of the reasons that you see them naturalised along railway embankments, where they were thrown over garden fences in frustration, and where the strongest can compete with the buddleia and brambles.

Frustratingly, asters have recently been renamed; A. novae-angliae, A. novi-belgii, A. laevis, A. dumosus, A. lateriflorus, A. cordifolius and A. ericoides have become Symphyotrichum, while A. divaricatus and A. schreberi are now Eurybia. Whatever you call them, aster enthusiasts and nurserymen who are selecting and naming new varieties have honed them for their mildew resistance. This means that in the summer wait for their moment of glory, they help provide a sense of healthy expectation in the borders. They have also been selected for their clump-forming ability and the majority stay put until they need division. Depending upon the variety, this can be in four to six years. They show you when they need this by developing a monkish bald patch in the middle. Division of the strongest growth to the outer edges in the spring renews their vigour.  The aster trial with from left to right, A. ‘Vasterival’, A. ‘Calliope’, A. ‘Violetta’ and A. ‘Primrose Path’

The aster trial with from left to right, A. ‘Vasterival’, A. ‘Calliope’, A. ‘Violetta’ and A. ‘Primrose Path’

As I write, the sun is streaming down the valley at an ever-decreasing angle, having burned its way through a morning mist. We had the first frost in the hollows today, so I would say this was perfect weather for looking at my collection. In the penultimate week of October they are in their prime and they look their best in the softened light with the garden waning around them. I have spent the morning amongst them, taking notes and pushing my way through the shoulder high flower to trace them from top to bottom. I want to see if they have stayed put in a clump, and which ones can do without staking, as I’m aiming for there to be as little of that here as possible.

I am smarting, however, as I have committed the ultimate sin when running a trial, for six of the labels are missing, buried within the basal foliage (I’m hoping) or – less helpfully – snapped off when weeding. Of these six I am going to keep two that have shown themselves to be special and, through a process of elimination from studying photographs and my garden diary, I will find out what they are. The others will be found a metaphorical railway embankment. In this case a rough patch of ground where the sheep won’t get them, but where they can provide some late nectar for the bees.

I have just a small number of creeping varieties which I tolerate for their informality. Although most asters prefer to be out in the open with plenty of light, the first three here are happy to live under the skirts of shrubs or in dappled shade. Aster divaricatus, a plant that Gertrude Jekyll famously used to cover for the naked patch the colchicum foliage leaves behind in summer, is one of my favourites. I have seen it in North American woodland where it lives happily amongst tree roots and spangles the dappled forest floor in autumn. Although it will not dominate here, as it does in the States, and runs slowly, it does move about, the dark, wiry stems leaning and sprawling and pushing pale, widely-spaced flowers to a foot or so from the crown. Aster schreberi is similar to look at, with single starry flowers, though it is stronger and has taken off in my hearty soil. I will put it amongst hellebores, which should be man enough to fight it out in the shade under the hamamelis. I will let you know who wins in a couple of years.

Aster ‘Primrose Path’

Aster ‘Primrose Path’

Strictly speaking, I should be wary of Aster ‘Primrose Path’ for not only does it double itself in size every year, it also seeds. However, it is not a hefty plant, growing to just 75cm and, as it is also happy in a little shade, I am keen to keep it and use its ability to move around in the shadier parts of my gravel plantings around the barns. The flowers, which are small, but not the smallest, are a delicate lilac, each with a lemon-yellow centre.

Aster ‘Violetta’

Aster ‘Violetta’

Aster ‘Little Carlow’

Aster ‘Little Carlow’

Aster ‘Coombe Fishacre’

Aster ‘Coombe Fishacre’

Most of the asters for the new garden have been selected for lightness of growth and flower, as I want the plantings to be transparent, allowing views of the far landscape into the garden. All, with the exception of the semi-double ‘Violetta’, are single. I like to see the centre of the flowers and I want them to to dance or to sit like a constellation in space rather than blaze in a solid mass like ‘Little Carlow’. Growing to well over a metre for me here, this is a really good plant, needing little staking and being thoroughly reliable, but it is too floriferous for me, the flowers bunched tight with little space between them so that the weight of flower seems impenetrable. ‘Coombe Fishacre’, though also densely flowered, is certainly a keeper, the centres of the soft pink flowers age to a darker grey-pink to throw a dusky cast over the whole plant. It is good for being shrubby in appearance and self-supporting.

Aster turbinellus hybrid

Aster turbinellus hybrid

My absolute favourite Aster turbinellus (the Prairie Aster), is one of the latest to flower, its season running from October into November if the weather holds out. It is exquisite for the air in the plant, the foliage being reduced to narrow blades and the stems wiry and widely-spaced so that it captures the wind and moves well. I’ve used it in great open sweeps in the Millennium Forest planting as the finale to the season there. The flowers, which are a bright lilac and finely rayed, have a gold button eye. I have a form simply named Aster turbinellus hybrid that has darker stems and dark buds that may be proving to be almost better than the straight species. I will keep them both for now and they may well be lovely planted together for the feeling that they are related yet different.

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ also has a reduced leaf, although it is altogether more dense and arching in growth. It is proving a valuable contrast for the size of the flowers, which are tiny and held thousand upon thousand in arching sprays. Palest pink, this should almost be too pretty, but I have enjoyed the scale shift when it appears with the larger-flowered forms. Together they layer and billow like clouds and I’d like to see them take the garden in a storm of their own making. Come the spring, it is all too easy to forget about including these late season performers in a planting. The notes I am taking now will remind me of their importance at this time of year and will be a useful reminder when I make the divisions for inclusion in the new plantings.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

This year I have limited myself with the bulb orders as the newly landscaped ornamental garden is a year or so away from being ready for them. Bulbs are best placed where you know they can be left undisturbed so, in order for spring not to arrive without something new to look at, we have ordered a selection of tulips for cutting, a handful of Iris reticulata for pots and wild narcissus varieties to continue the ribbon that I am unravelling in stops and starts along the length of the stream at the bottom of the hill.

I started the ribbon when we first arrived, and have been adding to it every year with a couple of hundred bulbs. But that quantity of bulbs runs for just a small stretch, even if spaced in groups that smatter and appear at random among the leaf mould. So last year I grew impatient and ordered 500 and I’ve done so again this year to make the ribbon go the distance.

Our native Narcissus pseudonarcissus is most at home in open woodland where its young foliage can feast on early sunshine before the woodland canopy closes. I know them from Hampshire where they colonise hazel coppice on the lower slopes of the South Downs. Once they are established they clump densely, but the flowers rarely register as fiercely as the hosts of hybrid daffodils that you see littering parks in March. The wild daffodil is smaller in stature – just 30cm – and the flowers are fine, with twisting outer petals of pale primrose and only the trumpet a saturated gold.

Narcissus pseudonarcissus

Narcissus pseudonarcissus

Narcissus pseudonarcissus massed under the new coppice on the lower slope of The Tump

Narcissus pseudonarcissus massed under the new coppice on the lower slope of The Tump

Unlike hybrid daffodils Narcissus pseudonarcissus is slower to establish and will often sulk for a couple of years before building up to a regular show of flower. No matter, it is worth the wait and I have already started my relay. The fourth leg runs into the area on the lower slopes of The Tump where the ground is too heavy for wild flowers and too steep for hay making and where I have taken some of the field back to plant a coppice. The hazel and hornbeam are just saplings, but it is good to think of the narcissus getting their feet in ahead of the trees.

About three years ago my parents bought me a sweet chestnut for Christmas, which I planted alone in the coppice. It will be allowed to become a standalone tree to pool shade in the future and rise up above the rhythm of the coppice as it ages. Here I have started a drift of Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. moschatus, the white-flowered form of the native, which has been in cultivation since the 17th century.

The elegant, downward-facing flowers are ivory as they open, fading slowly to a chalky white in all their parts. It is a beautiful thing and will be distinctive in the dim shade of the chestnut. I planted these bulbs as a memorial to my father who died the year the tree was planted and at the same time as the narcissus flower in late March. This variety is hard to find and this year I have only been able to source 50, but I am happy to add a small number annually. I like that it will take some time to come together and for the annual opportunity that this gives one to ruminate.

Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. moschatus

Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. moschatus

Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. moschatus planted around the sweet chestnut

Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. moschatus planted around the sweet chestnut

The Tenby Daffodil, Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. obvallaris, is the final part of this autumn’s order. This brighter yellow flower is also a native and, as its common name suggests, is most commonly found in Wales and the west. I have bought just a hundred and plan to trial it in the sun on the banks at the top of the brook near the beehive. Knowing your daffodils before you put them into grass is really important, as once they are in they are a nightmare to try and remove if they are wrong. I want to be confident that they aren’t too bright for their position and flare garishly where they shouldn’t. This will be my first time growing them for myself, so I want to get it right.

A square of lifted sod

A square of lifted sod

Plant the bulbs two and a half to three times the depth of the bulb

Plant the bulbs two and a half to three times the depth of the bulb

I am planting a little late this year as the wild daffodils prefer to be in the ground in August or September. They will be fine in the long run, but the green leaf tips are showing already and I can see that it would be better for them to be drawing upon new root rather than the sap of the bulb to produce this growth. To plant I lift a square sod of turf by making three slits and then levering the sod on the hinge that remains uncut. I put the bulbs in three to five per hole and at two and a half to three times the depth of the bulb. The flap is kicked back into place and firmed gently with the foot to remove any air pockets. A moment or two stepping back and imagining the same scene on the other side of winter is a very satisfying way to finish the day.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 8 October 2016

We have had a remarkable fortnight. August at its best with heat in the sun and long cloudless days. Cracks have opened up in the ground that are large enough to slide my fingers into and the garden has responded accordingly with fruit ripening and plants racing to set seed. It has been the perfect time to gather, with a daily vigil to check on ripening and harvesting just as the seed is ready to disperse. It is a yearly ritual, which I can trace back over thirty years to my black opium poppies. I may have missed a year or two of scattering them onto new ground to ensure that I have them the following year, but I have always had their seed in store, just in case. The seed is a currency of sorts and I can always depend upon the next generation if I have some in my pocket. Saving and sowing seed is rewarding on many levels. First, it is free, and mostly plentiful. A pinch goes a long way, but sometimes you need more than a pinch to make an impression. Secondly, raising plants from seed gives you a full and rounded understanding of how a plant develops and what it needs at each of its stages of life to thrive. A seed-raised plant has a different value, for you have not skipped a step. It will have been in your care from the get-go and may also come with associated stories that trace directly back to its provenance; what it grew with and where, or who passed the seed on and why. The seed of Stipa barbata is like the point of a dart and drills itself into the soil vertically when the long, silvery awn twists and contracts above it

Seed-raised plants are prone to variability and just occasionally you might find that a form has something superior to its parent: more vigour, a difference in flower colour or the potential of resistance to disease. Ash-dieback is an issue that we are all dreading as it works its way across the country, but there is surely hope in the fact that ash are such prolific seeders, that maybe there will be a seedling, or a percentage of seedlings, that are naturally resistant.

Not all seed comes true and this has its advantages as well as its disappointments. I keep my Tagetes patula and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ at opposite ends of the kitchen garden, as they are notoriously promiscuous. If they cross-pollinate the deep, velvet-red of the ‘Cinnabar’ will be tainted, its crosses in the next generation slashed with yellow, with neither the electric tangerine colour of the pure species nor the richness of the named hybrid. It is good to keep them pure.

The seed of Stipa barbata is like the point of a dart and drills itself into the soil vertically when the long, silvery awn twists and contracts above it

Seed-raised plants are prone to variability and just occasionally you might find that a form has something superior to its parent: more vigour, a difference in flower colour or the potential of resistance to disease. Ash-dieback is an issue that we are all dreading as it works its way across the country, but there is surely hope in the fact that ash are such prolific seeders, that maybe there will be a seedling, or a percentage of seedlings, that are naturally resistant.

Not all seed comes true and this has its advantages as well as its disappointments. I keep my Tagetes patula and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ at opposite ends of the kitchen garden, as they are notoriously promiscuous. If they cross-pollinate the deep, velvet-red of the ‘Cinnabar’ will be tainted, its crosses in the next generation slashed with yellow, with neither the electric tangerine colour of the pure species nor the richness of the named hybrid. It is good to keep them pure.

Tagetes patula (left) and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (right)

In contrast the range of amethyst colours found in Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ are the delightful result of natural variance, coming in the darkest blue-purple and fading through grey-lilac and pink to off-white. For the last couple of years I have been harvesting seed from mine to build up stocks. The seed is prolific and I have broadcast some on the wildflower banks below the kitchen garden in the hope that they will find a window and establish in the sward. I have also sown a pot full of seed for a more controlled result. When sown fresh they come easily the following spring. A pot sown each year should provide me with the quantities that I need to make an impression. After sowing they should take three to four years to flower and it will be exciting to see the natural variability in the seedlings.

Tagetes patula (left) and Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (right)

In contrast the range of amethyst colours found in Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ are the delightful result of natural variance, coming in the darkest blue-purple and fading through grey-lilac and pink to off-white. For the last couple of years I have been harvesting seed from mine to build up stocks. The seed is prolific and I have broadcast some on the wildflower banks below the kitchen garden in the hope that they will find a window and establish in the sward. I have also sown a pot full of seed for a more controlled result. When sown fresh they come easily the following spring. A pot sown each year should provide me with the quantities that I need to make an impression. After sowing they should take three to four years to flower and it will be exciting to see the natural variability in the seedlings.

Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ showing the natural colour variation in the flowers

Self-sown seedlings are an indicator that you have found a place that suits a plant. This is my ultimate goal in the garden here: to work with the conditions and what the plants favour and for self-seeding to create a ‘blur’ in some of the plantings that allows them to take on their own direction.

Camassia leichtlinii ‘Avon’s Stellar Hybrids’ showing the natural colour variation in the flowers

Self-sown seedlings are an indicator that you have found a place that suits a plant. This is my ultimate goal in the garden here: to work with the conditions and what the plants favour and for self-seeding to create a ‘blur’ in some of the plantings that allows them to take on their own direction.

Seed collected this summer

The seed gathering started last month, each new collection stored in a reserve of pie boxes which make the perfect receptacles. The boxes are left open on a sunny windowsill until the seed is thoroughly dry and then labelled for clarity. Not all seed is for keeping. Umbellifers, for instance, and plants from the family Ranunculaceae are best sown fresh as the seed degrades rapidly. Sown now, and depending upon the species, they will sit in their pots until spring and have their dormancy broken by the stratification of frost. Peonies may take up to two years to germinate. The first year will see roots forming and nothing above ground, the second spring will give you the first leaves, so sometimes patience is important. Other seed such as scabious and Succisa come up almost immediately, so that they are past the seedling stage in order to overwinter as youngsters and get away quickly in the spring.

Seed collected this summer

The seed gathering started last month, each new collection stored in a reserve of pie boxes which make the perfect receptacles. The boxes are left open on a sunny windowsill until the seed is thoroughly dry and then labelled for clarity. Not all seed is for keeping. Umbellifers, for instance, and plants from the family Ranunculaceae are best sown fresh as the seed degrades rapidly. Sown now, and depending upon the species, they will sit in their pots until spring and have their dormancy broken by the stratification of frost. Peonies may take up to two years to germinate. The first year will see roots forming and nothing above ground, the second spring will give you the first leaves, so sometimes patience is important. Other seed such as scabious and Succisa come up almost immediately, so that they are past the seedling stage in order to overwinter as youngsters and get away quickly in the spring.

Seed of umbellifers, such as Opopanax chironium, must be sown fresh

I like to sow in a gritty mix for maximum drainage and find that if the seedlings have to search for moisture they develop a better root system. Seed is scattered as lightly as possible across the surface so that the seedlings have room to develop their first true leaves before transplanting. I like to top-dress the seed with horticultural grit, again for drainage and also the advantage of protecting the seedlings from the soft underbellies of slugs and snails. The pots are stored in the controlled environment of the cold-frame where I can keep an eye on watering, and so that they do not lie wet in winter. Seed for keeping, such as the annual tagetes, will be kept dry in Tupperware in the back of the fridge to slow their degradation and brought to life again next spring with the summer stretching ahead of them.

Seed of umbellifers, such as Opopanax chironium, must be sown fresh

I like to sow in a gritty mix for maximum drainage and find that if the seedlings have to search for moisture they develop a better root system. Seed is scattered as lightly as possible across the surface so that the seedlings have room to develop their first true leaves before transplanting. I like to top-dress the seed with horticultural grit, again for drainage and also the advantage of protecting the seedlings from the soft underbellies of slugs and snails. The pots are stored in the controlled environment of the cold-frame where I can keep an eye on watering, and so that they do not lie wet in winter. Seed for keeping, such as the annual tagetes, will be kept dry in Tupperware in the back of the fridge to slow their degradation and brought to life again next spring with the summer stretching ahead of them.

The first of this year’s sowings ready for the cold-frame

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The first of this year’s sowings ready for the cold-frame

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan This week has been an important one. The digger men are here, carving out the new garden and shaping the land around the house. A great divide of mud has marooned us. Venture out in any direction and you are met by instability.

There is nothing like the crunch of a decision having to be made to focus the attention on what you really need to keep. I have been taking out roses in full bloom to make way for new paths. After holding on for as long as I could, it was strangely liberating. A running rudbeckia and the bolting boltonia are now on the compost heap. I’ve been curtailing their spread since they came here, despite knowing that they were trouble. The inulas that were grown from seed are sitting in a heavy un-liftable knot that was levered by the digger and covered with damp hessian ready to be divided and potted up this weekend. Their removal has tuned my mind to decide where I eventually want them.

In planning for this moment I planted a sanctuary bed that runs at the front of the house, locked in by the path. Most of the plants here were grown from seed. You care more for seed-raised plants somehow and their volunteer seedlings have shown that they like it in this spot. Today’s posy illustrates something of the transparency in the planting. I want to see through it, for it to be light and for it to shift against the weight of the walls of the house. Yellows and greens and browns are the backbone of the planting. Of the half dozen in the bunch, the greater number are umbellifers. They make wonderful companions in associations that are naturalistically driven and bring the same feeling into a bunch.

Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’

Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’

I have grown bronze fennel forever, liking the way it is from the moment its new growth pushes through to the point at which I have to cut away last year’s skeletons to make way for it. It loves our ground here, the sunshine and the free draining soil, so I only leave the plants standing over winter where I know the smoky haze of new seedlings can be managed. Now they are just showing flower, which has pushed free from the net of dark foliage. Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’ looks good with almost anything and I love the horizontality of the gold umbels when they mass more strongly later in the month.

Bupleurum falcatum

Bupleurum falcatum Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’

Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’

The acid-yellow umbel in the mix is the biennial Bupleurum falcatum. I threw fresh seed into the rubble around the barns and potted some up to plant them where I wanted them. They have just started to flower and will continue to form a bright cage of flower, so small and filamentous that it creates a haze of vibrancy. Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’ is it’s perennial cousin. I shall write more on this later as it is an old favourite that deserves more time.

Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum

Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum

Thalictrum flavum ssp. glaucum rises up and above most of its companions on wire thin stems which catch our breezes, but there is no need for staking until they hang heavier with seed. I cut them to the base to avoid the seedlings at this point as the clumps are long-lived and you need just a handful to make an impression. The fluffy flowers are a pure sulphur-yellow and the leaves are the blue green of cabbages but fine, like lace.

Lonicera periclymenum ‘Graham Thomas’

Lonicera periclymenum ‘Graham Thomas’

This is a good selection of the wild honeysuckle called ‘Graham Thomas’. I first saw it growing on his house when we were taken to meet him as Wisley students. I had no idea then how influential a plantsman he was, nor how much I would have enjoyed his namesake all these years later. I much prefer it to the brickier, shorter-flowering varieties such as ‘Belgica’ and ‘Serotina’. It also flowers far longer than its native parent and, after its first July flush, continues off and on into September.

Hordeum bulbosum

Hordeum bulbosum

The bulbous barley, Hordeum bulbosum, was collected on a trip to Greece a few years ago. It has proven to be completely perennial, retreating to a basal cluster of storage organs after flowering. I cut it before it seeds to limit its spread, as it germinates freely. In Greece the storage organs (which give it its species name) would keep it alive during a summer without rain to reactivate growth in the autumn. Here, without a water shortage to speak of, it is happy to return with a second flush in September. The flowers are early, rising in April, to trace every breath of wind outside the windows.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The globe artichokes (Cynara cardunculus Scolymus Group) were some of the first plants to go into the new kitchen garden. They are a luxury vegetable, taking far more space than they provide reward for and shading their neighbours if, indeed, there is room left in their shadow. Nevertheless, I gave them a bed to themselves, in prime position and against the radiated heat of the newly built wall.

They have grown in spectacular fashion – which is the greater part of the reason for having them – doubling and trebling their bulk in the course of the first summer and continuing onward to take all the space which was offered them. Cold weather in combination with winter wet is their nemesis but, since they were planted, both winters have been mild and they have only had a brief down time in the darkest months when they retreat to a core cluster of leaves.

Their aluminium foliage is wonderful in its ascendancy and as good as acanthus in its architecture. As soon as the weather warms in March it reaches from the clump, each leaf larger and more dramatic than the last, scrolling and bulking steadily until you see that, some time in May, the parent foliage has gathered enough energy for the flower spikes. These push proud of the forest of leaves, but it is whilst the heads are small that you need to curtail their reach and harvest the artichokes.

We grow a variety called ‘Bere’, which Paul Barney of Edulis Nursery offers, and is the selection his father found growing in the walled garden there in the 1950’s. It is spinier than some of the named varieties, but Paul says it is the best tasting of them all. Indeed, it is a wonderful plant if you pick the heads whilst they are still young and before they are fully armoured. The best and meatiest parts are still soft when the leaf spines are forming, but leave them to harden and fulfil their thistly leanings and you end up with an impossibly fibrous mouthful.

Cynara cardunculus Scolymus Group ‘Bere’

Cynara cardunculus Scolymus Group ‘Bere’

I plan to split my clumps in the spring, when growth is on the move and the crowns are manageable. Being mediterranean, they start life as soon as there is warmth and moisture in combination but, being sensitive to the cold, you have better chances in spring than if you move them at end of the season. It is a two-man job to lift the clumps and then prise a division, with root, from the clump. The divisions or ‘starts’ will be planted in the new herb garden, where they will provide ornamental architectural structure amongst the herbs.

I have six plants now, far too many of the same variety, so the plan is to thin the ‘Bere’ to three and equal it with the same number of purple-tinged ‘Romanesco’ to make up the half dozen. ‘Romanesco’ is an altogether friendlier plant without spines, and the scales that form the thistle head are soft and can easily be harvested and prepared without the need for gloves.

Each plant will be spaced a metre apart and inter-planted with stands of bronze fennel, which will cover for the artichokes’ collapse, which happens in high summer once all their energy has gone into flower production. At this point, once the old leaves start to fail revealing bare ankles, it is best to cut the lot to the ground and let the foliage regenerate. It will be back for the autumn, whilst the fennel covers during the recovery period.

In Italy the cardoon is also prized in the early spring for its edible leaves. The midribs, which look like celery, are stripped of the leaves and fibres, and then blanched and buttered, or baked in a gratin. You need rhubarb amounts of room for such a short season vegetable, but if you do have a spare corner in sunshine they are sure to provide you with drama at the very least.

I first grew the ornamental cardoon (Cynara cardunculus) as a border plant at Home Farm. Innocent looking divisions arrived from Beth Chatto, as beautifully wrapped in damp newspaper as they are described in her catalogue. They were planted in an ambitious group of three on a sunny slope and took their position, rearing up in a mound of metallic foliage. Tapering in August to a magnificent pinnacle of branching flower, the plants reach about three metres in height, and need staking if they are not to topple once the flowers break colour. Look up and you see bees staggering about drunk on the fist-wide pools of neon violet filaments.

The butterflies love them too, but the giant needs to be felled if it is not to leave you with a gaping hole once the collapse starts to happen. At Home Farm I planted it within a corral of late summer perennials, spaced at a sensible distance so that they can swallow the hole whilst it regenerates. Asters and rudbeckia will do the job, but you have to give the cardoon space in spring as it is an early season riser.

Cynara cardunculus ‘Dwarf Form’ with Centranthus lecoqii

Cynara cardunculus ‘Dwarf Form’ with Centranthus lecoqii

Fergus Garret pointed me to a dwarf form that they have in the garden at Great Dixter and I grow it here against the barn. I am not usually a fan of plants selected for dwarfism, but this cardoon makes for a better-behaved plant. It is distilled in all it’s parts, and more evil to the touch, the undersides of every leaf defended with an armoury of needle-sharp spines. Its foliage is as beautiful, possibly more finely divided, and certainly more compact. It tops out at about a metre and so avoids the need for staking. In the border where I grow it with Centranthus lecoqii and Romneya coulteri it has taken it’s territory, but the repercussions are altogether more manageable, and I still feel I have the drama I am looking for.

Cynara cardunculus ‘Dwarf Form’

Cynara cardunculus ‘Dwarf Form’

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

When we arrived here the flat ground was literally no more than a strip in front of the outbuildings. We perched a table and chairs there to make the most of not being on the angle. The floor of the boot room and those of the outhouses, the barns and levels of the farmyards were a patchwork of concrete, poured in mismatched batches and at a rake with the slope. The acuteness of the land had been diminished to create these spaces, but only enough to ease the grade. I didn’t know until we set out to create a new level why the farmer before us had minimised his excavations. Cut into the land and you quickly find the spring line.

Autumn 2012

Autumn 2012

Two summers in it was clear that we needed a dedicated garden for fruit and vegetables. They were being challenged for space in the trial garden and we had become tired of negotiating the slopes for the detailed work that is part of growing your own. Sowing, thinning, weeding and harvesting on a slope were all that much harder with one leg shorter than the other and tools and buckets balanced. Beyond the tin barns the newly planted orchard was beginning to show, and the barns were the natural anchor point for a productive garden. We planned to grow figs and espaliered pears against the south facing breeze block walls of the barns and, on newly flat ground, soft fruit and vegetables, both annual and perennial.

October 2012

October 2012

The first step in the process was made in October 2012 with the installation of a pair of monolithic 18th century granite troughs. I had three in total, brought all way from Yorkshire, but originally from eastern Europe where they had been used for tanning leather. They were magnificent things and I planned a pair as a division between the house and the long view west to the new kitchen garden. It was a Herculean task to get them in place. Each weighed four and a half tonnes and, in combination with the fifteen tonne fork-lift used to move them, the track collapsed and the concrete farmyard literally buckled under their weight. In the process we lost the drains from the house as the fork-lift crushed them, but my landscaper who was driving never flinched as the trough tilted the machine at a perilous angle. We threw rubble into the ruts and started again and, though it took all day to inch them to where I wanted them, they eventually reached their positions.

October 2012

October 2012

I wanted the troughs to sit as an offset pair, running across the spine of the new level that links the house with the barns. Here they would act as a gateway to the vegetable garden, while also screening it from the house and defining the space. Their bold outline would echo the straight line of trees on the distant horizon. One would be filled with rainwater from the roofs for hand-watering, the other would eventually be fed by the disused hydraulic ram pump down by the brook in a long-term plan to refurbish it. When you passed between them, an orderly set of beds would run like ribs north south off the east, west axis. The orientation of the beds would allow for the best and most even light for each of the crops.

September 2013

September 2013

Nearly a year later in the last week of August and riding good weather for the best part of three weeks, we started the land-forming to create the garden beyond the troughs. The digger scraped back the slope to make a spine of flat land between the house and the barns, while another cut made to level a sloping track in the field above the house provided the subsoil to make up the level from the barns. A breeze block wall was made to hold the land to the upper side of the spine, and provided the garden with a wall for espaliered pears and shelter for vegetables that would like the radiant heat – an asparagus bed, globe artichokes, courgettes and climbing beans. Breeze block felt like the right material to use as it sat well with the agricultural aesthetic in which things had been built in the past.

September 2013

September 2013

The topsoil, and the turf that came with it, were harvested and piled in the field below the new garden. It was stacked wider than it was high at 4’ or so, because if you stack soil higher the soil bacteria at the bottom of the pile get smothered and the soil becomes infertile. The sod rotted down to add organic matter, as the pile had to stay where it was until the following summer for, in mid-September, the rains came and made the site unworkable.

The scraping revealed the rubbly limestone brash that was perfect for making up the levels, but the brash sat on clay and, as soon as the rains came, a number of springs that had been moving through the slopes unseen, began running over the surface. As luck would have it, we had poured the footings for the wall by this point, but the workmen suffered, moving through the mud in slow motion to build the wall and then constructing a series of steel-edged beds. Mud stopped play not long after but, as soon as the weather was dry enough the following spring, the beds were soiled up to the depth of a generous spit.

September 2013

September 2013

Spring 2014

Spring 2014

I graded the beds, starting with narrow metre wide beds at the windward westerly end of the garden. These were planted with the woody currants, gooseberries and raspberries to provide some wind protection. All the paths between the beds are a metre twenty wide to allow plenty of room for a barrow and growth to encroach from either side. The beds scale up in size to one and a half metres and then two metres wide, but no more, so that it is easy to work the beds from either side without having to tread on the soil more than necessary. That first summer we left the majority of the beds fallow, removing perennial weeds and mulching them with manure, which we dug in over the winter. We did plant a couple of the beds with brassicas and winter sown broad beans to make us feel like we were moving in the right direction.

Last year was our first summer growing in this new space and we are learning again with a new position and the challenges that come with it. Our knees and backs are certainly better for the flat ground – we can move about freely without having to watch our step – but we are finding that some crops are missing the protection afforded by the hedge in the old garden. We are working on the soil with our own compost this year and talking about making a couple of the beds no dig next year. But for now, the summer and whatever it will teach us, lies in waiting.

Spring 2016

Spring 2016

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Dan Pearson & Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage