As I write, the valley is unified by a deep freeze. Deep enough for the ground not to give underfoot and for the first time this winter an icy lens is thrown over the pond to blur its reflection. The farmers use this weather to tractor where they haven’t been able to for the mud. The thwack of post drivers echoes where repairs need to be made to the fences and slurry is spread on the fields that have for a while been inaccessible. It you are lucky, this is exactly the weather when you might get your manure delivery.

I welcome the freeze in the garden, for the last few weeks have been uncannily mild. Warm enough to push an occasional primrose and a smatter of violets. This year we have early hellebores, rising already from their basal rosettes and reminding me to cut away last year’s foliage so that the flowering stems can make a clean ascent. Good practice says to remove the leaves in December to diminish the risk of hellebore leaf spot. So far, whilst I have been nurturing young plants, I prefer to see the flowers pushing before I cut and know that the leaves have done all they can to charge the display.

As the garden matures it is already leaning on me to step in line where in its infancy I retained the upper hand in terms of control. I chose to wait until the end of February before doing the big cut back all in one go to allow as much as possible to run through the season without disturbance. Not so just five years on. I need to start engaging if I am not to make things more and not less labour intensive. It is all my own doing of course, because the more I add to the complexity of the garden, the earlier we have to start to be ready for spring. Where I have planted bulbs amongst the perennials for instance, the bulbs demand that I ready these areas to avoid snubbing their noses.

In terms of letting things be and allowing the garden to find its own balance, I want there to be a push and a pull between what really needs doing and where the natural processes can help me to tend the garden. The fallen leaf litter is already providing the mulch I need to protect the ground under the young trees, so it is in these areas I am concentrating the plants that need early attention. The hellebores and their associated bulbs can now push through the leaf litter. I no longer have need to mulch in these areas and save the annual trim to the hellebores and the shimmery Melica altissima ‘Alba’, the balance here is successfully struck.

We try to get our winter work, which tends to be bigger scale and mostly beyond the garden, all but done by the end of February. Our own fence and hedge work, tree planting and pruning. The ‘light touch’ beyond the garden will see us strim the length of the ditch before the snowdrops come up, but leave it standing for as long as possible where there are no bulbs. We come back on ourselves before the primroses start. Being further down the slope and colder, growth is later there, but the end of February date works. We leave the coppice beyond the ditch untouched, hitting the brambles every three or four years to curb their domain, because the coppice also needs time to establish without competition. Beyond that, and in the areas where we are letting the banks completely rewild, we watch the brambles spread and note how quickly the oaks that have been planted by the jays and squirrels, spring up amongst them. One day the shadow will put pressure on the brambles, which will fall in line and not be the dominating force. Watching what happens and applying your energies only to what is needed is a good reminder for what one should be doing as a gardener back in the cultivated domain.

The tussocky slopes that are too steep to cut on the hay meadows are a beautiful thing. They are very different as a habitat from the machine-managed sward that is kept in check by the hay cut, the grazing and the associated yellow rattle, which will only grow there where it is not outcompeted. The contrast of the tussocky land nearby with its peaks and troughs created by the grazing animals and not a combine provide a place where the rodents live and in turn where the owls and raptors come to feed. In summer you can look into these miniature landscapes and see the other world they offer for yourself. The cool side of a tussock and the warm side where the butterflies bask and the different webs or spiders that take advantage of the peaks and hollows of the undisturbed ground. From our own perspective as custodians and drivers of what happens here, the tussocky ground is a beautiful reminder. Catching the low winter light, its contours draw you to remember that it is good to touch down lightly where you can afford to and only apply your energies at the right time and in the right place.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 22 January 2022

Suddenly the violets are in bloom, an invisible cloak of perfume that hangs heavy by the milking barn. They are planted for exactly this moment, on the bank by the path, in the lea of the building and where the early spring sunshine unlocks their early blooms and bounty. The surprise, when walking into their orbit that first spring day makes you instantly breathe deep.

The handover from winter to spring started in the third week of February and in reaction to a week of hard freeze. The catkins on the hazel fell like streamers being shot from above at a party and the silken pussies on the willows gathered in number and glistened in light reflecting shoals. A windy few days, which saw the gales leaning heavily into the garden put paid to the snowdrops, but in a perfectly orchestrated handover, the primroses were there to replace them. One or two at first and, within just a couple of days, more than you could count and running away into the distance where over the years we have been splitting and dividing.

Although it comes with a little sadness to be clearing the garden, the push of the new has made way for change. Old stems now feeling tired for the contrast of fresh buds at their base and the expectation of spring applying a mounting pressure to move on and make way.

Each year since we planted the garden, the clearances have revealed a place that is slowly hunkering down and becoming itself. The layering I had planned for and that only comes with time. Pulling back the old growth and cutting it to the base is always a good time to look and see what has really been going on under the cover of a growing season. Asters that are on the verge of running riot where they have got the upper hand on their companion. The sanguisorba that this year will need dividing to prevent them from toppling mid-season.

The clarity of the clearance also reveals the interlopers. This year it is a running epilobium which has jumped from the nearby ditch with wind-blown seed. Growing away happily and out of sight it has set up home with a mother plant and she has begun to run. Ducking and diving and popping up a new and lustrous rosette like a mole throwing up hills. Fleets of arum seedlings have also made their way in through birds that have been resting up in the spent stems of winter and pooping. The parent plants, which now have a lusty presence in the garden hedge just a few strides away, have obviously been sizing up the ‘open’ ground of the garden. Beth Chatto warned me about the Arum italicum which had taken over her woodland garden. “It is a terrible weed.” she said, “Watch out for it!”. I have been and I will, each seedling carefully removed with a long-bladed trowel, being very careful not to leave the pea-sized corm at the base.

Pull away the old growth and you find the evidence of life that has been going on under cover. Scatterings of a specific stripy snail shell, smashed around a stone where the thrushes have made their makeshift anvils. Nests of mice and voles under the thatch of the ornamental grasses. You can imagine how cosy it must have been as you pull the old growth away to expose the evidence of their foraging. Neatly gnawed holly berries and what I’m thinking might be the dismantled seed heads of the Agastache nepetoides that I’d been looking forward to for their blackened winter pokers. They mysteriously vanished over the course of a week in the autumn.

As the garden grows and becomes its own ecosystem, every year demands a specific response to retain the desired balance. I made a start this year in January where I’ve been planting bulbs and early woodlanders in the shelter of the shrubs that are now casting their influence. The Cardamine quinquefolia are already showing green when most of their companions are sleeping. Running happily amongst the dense rosettes of foliage cast by the hellebores, they make perfect company if you cut the hellebore foliage in December when making way for the flowers. The cardamine will have done its feeding and be flowered and dormant again, their short life above ground stored in wiry rhizomes and done by the time the foliage takes its space back on the hellebore.

The big clear up at the turning point between winter and spring takes place in the cross over of February into March. We take three weekends usually with the middle weekend being with invited enthusiasts and many hands on deck. Not so this year, the year of things being less social and more distanced. So the clearance will happen over a month and take another week to work our way clockwise. From the top where the Allium ‘Summer Drummer’ is already etiolated with its early growth drawn up into last year’s skeletons. We will then pass around the outside where the pulmonarias are blooming in the sun and need to be liberated and enjoyed. Finally we will draw back in to the centre, the most complicated of the beds where the detail and fingerwork is intensified. It is a process of reveals and observations, decisions and actions. One leading to another and spring engaged with through the doing.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 March 2021

With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

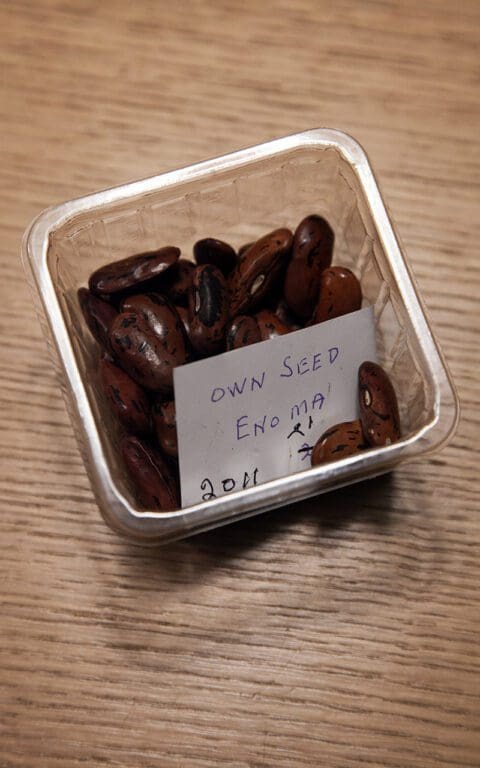

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

The garden has just come through its third growing season. Three years in and we already have to push our way down the paths, which were made deliberately wide for exactly this moment. Two paces of width felt generous in the first year, but now I am pleased for the breathing space with the garden at its absolute fullest.

Three years will usually see the perennials enmeshed and what you had imagined of a composition. It takes around five for the trees and shrubs to start to register, to throw shadow and to rise above the seasonal plants that come and go. This is the first year we have enjoyed the arc of hips on the Rosa glauca and a taste of what the colouring Euonymus planipes will become once it is doubled in size again and casting a new and shadowy microclimate.

The fifth year after planting is usually a time of building in change to compensate for the newly cast shade of the woody plants or to revitalise the fastest growing perennials that might already need splitting. Not so here. Our hearty ground and sunny slopes have come with the challenge of plants performing faster and more furiously than usual and I am already thinking about my edits. Stepping into the beds from the open pathways and you are immediately dwarfed. Echinops which, to my surprise, were nine feet tall when I ventured in to cut them out to prevent them seeding. Actaea that I hadn’t seen all summer, happily sitting in the cool of towering sanguisorbas, yet all but invisible from the viewpoints of the paths.

The sanguisorbas are this year’s project. My three year trial, which sat on this very ground before the garden replaced the test beds, contained about fifteen different varieties of which half were retained as the best. My trial, with its regular rows and spacing to enable close observation of each singular plant, did not allow for the conditions now the garden has developed its own microclimate. The depth of the beds has allowed the community of plants to work together, protect the ground and diminish the weeds, but the community is never static and for it to remain in balance it is timely to plan some gentle intervention.

The sanguisorbas register well en masse with their suspended thimbles acting like a veil and atomising colour. Used liberally and in drifts they allow for more acute punches of concentrated colour to appear to hover in suspension; vernonia, now for instance, or a mass of aster. My plans worked well in the first year, but slowly, as the sanguisorbas have developed heft with our soil providing them with everything they need, they have become the largest person in the room and have started to lean upon their neighbours.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ was the first to need more attention and last year I staked it, to prevent the weight of flower toppling after rain. I am trying to stake as minimally as possible here, so this year I tried an experiment, cutting half of the plants completely back to the ground once they started to ascend in the middle of May. A ‘Chelsea Chop’ would usually halve the height in the last week of May to promote sturdier regrowth, but I wanted to diminish their vigour and see if I could get lightness back into the second round of regrowth. It felt entirely wrong being this drastic when the garden looked so pristine in the first week of summer, but in no time they were back and have gone on to be lighter and less weighty than those that were left to do their thing.

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’ has such handsome early foliage that it would be entirely wrong to attempt the same treatment, but the plants are nearly ten feet tall and leaning, each of them half their height into their neighbours. The plan come the spring is to remove about a third of the group to make more space for the Actaea cordifolia ‘Blickfang’ planted amongst them and then start a yearly round of splitting a third of them so that there are always three generations. The range of ages provides an immediate lightness, the younger plants standing straight and aspiring to the full-blown display provided by the elders. Sanguisorba tenuifolium ‘Korean Snow’ has similar habits and will be treated accordingly to see if my efforts avoid having to stake and retain the ‘air’ in the planting.

In making my notes for change, I am marking the plants with canes so that I am less reliant on my memory to open up breathing space come spring. So far S. ‘Blackthorn’, with its upright long-fingered thimbles and S. tenuifolia ‘Stand up Comedian’ are behaving better. As are the flamboyant S. hakusanensis. Midori, the head gardener at the Tokachi Millennium Forest, describes these plants as like large birds sitting in their nests and, indeed, you need the space to allow them to huddle low and to splay. The September assessment, and then the gentle changes that result from it, will be the way forward if I am to retain the balance and an engagement with change.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 19 September 2020

So everything is different. And changing daily. We have been here in isolation for just over two weeks, having set up the studio to work remotely and feeling very fortunate to be regaining balance from our perch on the hill. We know, more than ever, that we are blessed with this access to landscape and fresh air and to be able to witness spring unfurling around us. A spring that is oblivious to the change in the worldwide order. A welcome tide that carries on regardless, providing a sense of continuity and solace in its inevitability.

We have been in two minds about doing this piece today. The world is on the brink of a big change and we know that we are in a position of privilege. We are all experiencing multiple wake up calls. I have been using Instagram more than usual in the last couple of weeks trying to maintain a connection to normality. We have become acutely aware of the people who do not have access to what we have access to and, by sharing it, we have found the pleasure it gives those who are in real isolation. In flats, in cities, with no outside space and suddenly without liberty. So, in the spirit of sharing, this is the beginning of our new world.

Last weekend already feels another lifetime away. Jacky and Ian were here to try and get the mulching done before lock down. There was a palpable tension in the air, because they had ventured away from their own home sanctuary to help us, but it was a good day going about the usual tasks, despite the social distancing. We got half the mulching done. Ten of twenty tonne bags and half the garden smartened, fresh growth green against the new eiderdown of darkness. Ten tonnes remains in the drive to mark the fact that we are now on our own. For how long we do not know.

The fear of how we will look after everything has been rolling round my mind. Jacky and Ian supply an invaluable day each on Saturdays. Jacky providing detail and Ian strength and stamina in the areas beyond the garden that we keep on the wild side. When we work together we get more done as a team. Without their input, we are having to quickly re-evaluate to establish a new regime and look at how we approach this undefined period.

What we are doing here probably amounts to about five man days per week. I run a tight ship with that time too, with lists to hit targets and an eye on the near and far future to keep things moving in the right direction. There is very little slack and we are ambitious for this place; for the garden to be evolving and experimental and for the kitchen garden to provide food for us to eat. We are also steering the ecologies towards greater biodiversity and this is where we will probably have to let go of the reins and let nature really do its thing. There will be no paths mown into the lush growth of early summer. Instead, we will push our way through to make our desire lines. But as much as possible, I’d like not to go backwards. So, simply put, we will have to find two days from somewhere. Two days of our time that is currently devoted to the new challenges of running a virtual studio, finishing a book and keeping up with friends and family at distance.

I was talking about the dilemma, or indeed the opportunity, of this change with my mother who is now isolated in Hampshire and needing more regular calls. Being a practical and sensible woman she put three things forward. Firstly, that we simply won’t be able to do everything. Second, that a garden can be reclaimed from a period of wooliness. And third, that we should chart the changes in Dig Delve to communicate the impact a world in flux is having upon our ground at home and our relationship with it.

A few sleepless nights have already been eased by the prospect of having to apply ourselves differently and the garden is helping to tilt the balance of anxiety in the right direction. Without needing to travel for work I will reclaim that time to garden. Up early now and putting an hour or so in before our business-not-as-usual kicks in, I have been able to take in the spring more intimately. Seedlings are already benefitting from a daily vigil in the frames. A meditative hour pottering before breakfast is a purposeful way to greet the day and helps to clarify the mind. As the evenings lengthen there will be more time freed up to engage with day to day tasks and so we will be able to see like we’ve never had the time to do before.

Together, the two of us will make sure that over the next fortnight we get the remaining mulch onto the beds. My job list for this month (always with the caveat ‘weather dependent’) had us all doing it together. Four bodies and one day to complete the task. We will balance the hard graft over a longer period, with the detail of setting the kitchen garden up for the season. Until now, growing to eat has been a choice. To eat seasonally and organically and with the pleasure of being able to say it’s all from the garden and never fresher. Our perspective on sustaining ourselves here is suddenly heightened and the ability to grow our own food thrown into sharp relief. Choice has now become necessity. Where there is a surfeit, we will be harvesting more keenly. Bottling, freezing and learning how to ferment and pickle so that the harvest carries our efforts further. Where we struggled to keep up with successional sowing in previous years, we will apply a sharper eye to make sure that the beds are used as efficiently as possible. I am not saying it will be easy, but we will feel the difference for a life lived in real time.

So how will we all cope ? Gardens that we have been planning and building for years are suddenly without their gardeners this summer. Our project to re-imagine Delos at Sissinghurst is freshly planted and designed to feel like a wild place. The new reality of only a skeleton staff to look after it may find us returning to a wildness accelerated. At Lowther Castle, where the new Rose Garden – 10 years in the planning – is planted but not quite finished, will now have just two gardeners at a time looking after the acres of grounds in their entirety. The garden was due to be opened to the public this June, but now it seems the roses will come into their first life together as if in a secret garden, with the lawns grown long and the stillness of a garden unpeopled. These are extraordinary times. A period of rare reflection for most of us. A time to go deeper. What do we really need ? What are the real priorities ? How can we better our world and be kinder to it and each other when the dust settles differently ?

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan & Dan Pearson

Published 28 March 2020

Stripping away the last season’s skeletons comes with mixed feelings and I judge the moment carefully. There has been joy in the leftovers and I have savoured the falling away, with each week revealing a new level of transparency, but no less complexity. Light arrested where it would have fallen without charge or definition if we had cut the garden earlier and the feeling that we are more in tune for standing back and going with the winter.

It has all been worth the wait, but by mid-February, when the snowdrops were drifting in the lane, the need to move became clear. The tiny constellations of spent aster were suddenly joined by the willow catkins on the Salix gracilistyla that nestle by the gate. Grey buds like moleskin, soft, glistening and alive with bees. The old growth alongside them was made immediately apparent and the need to embrace the change an easy step to make.

This spring, after completing the planting the autumn before last, we have twice as much garden to clear. This time last year two working days with three pairs of hands saw the skeletons razed and taken back to base. With more to wade through this year four of us made a day of it the first weekend to break into the oldest parts where the perennials have now had two summers of growth. The weather had been dry and the soil was good to walk on without feeling like you were straying from the path. The sun came out to fool us into thinking it was April and, sure enough, at the base of the remains there were clear and definite signs of life. Buds red and rudely breaking earth already on the peonies and emerald spears of new foliage marking the hemerocallis.

I worked ahead of the team, stepping into the planting where I’d spent the winter analysing the plants that needed changing or adjusting. Last year it was to remove all the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’, which were replaced by Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’, a form that feels closer to the wild loostrife. This year, I have lifted a stand of Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’ by the lower path that were shielding the planting below them. They have done better than I had thought, so half were tied in a topknot to make them easier to move and then staggered through the beds where I need this accent and volume for late summer and then winter. I left them standing to check how they marched and jumped through the planting to bring it together. Now is the time to move grasses, for they engage fully with dormancy early in autumn and with life in root activity in early spring. Being late season grasses, I have placed the panicum where they will not be overshadowed too early by their neighbours. The two year old plants were a handful to heave, but with a sturdy root ball they will not look back. With spring now on our side, the timing should be perfect.

I have not planted bulbs yet, or not as many as I am ultimately planning for once I have more maturity in the planting. I will keep them in groups under the trees and shrubs where their early season presence can be allowed for. Planted too extensively amongst the perennials and I would have to cut the garden back sooner, at least two weeks earlier, so as to not trample their emerging shoots. As the willow catkins are my litmus, I will let them determine the date that the skeletons are cleared and not be driven by the march of bulbs. That said, there will be exceptions. I have a tray of potted Camassia leichtlinii ssp. suksdorfii ‘Electra’ that were impossible to plant in the autumn when the garden was still standing. They will find a home where I have lost deschampsia to voles. This is the second year running that their homes have undermined this layer in the planting and it feels more appropriate to bend and change direction.

The new start with a clean palette reveals a gap in this new garden. One that, with time to get to know the new planting, I can now plan for. Early pulmonarias are already bridging the space beween the winter skeletons and the real beginning of spring. I have planned for more P. ‘Blue Ensign’ so that it’s gentian blue flowers can hover under the willows. Shade tolerant ephemerals such as Cardamine quinquefolia and Anemone nemorosa will also be useful to weave amongst later clumping perennials that can take a little well-behaved company in the spring whilst they are still just awakening. The layering will be important as I get to know more and, in turn, become more demanding.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 March 2019

We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast. I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing. The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

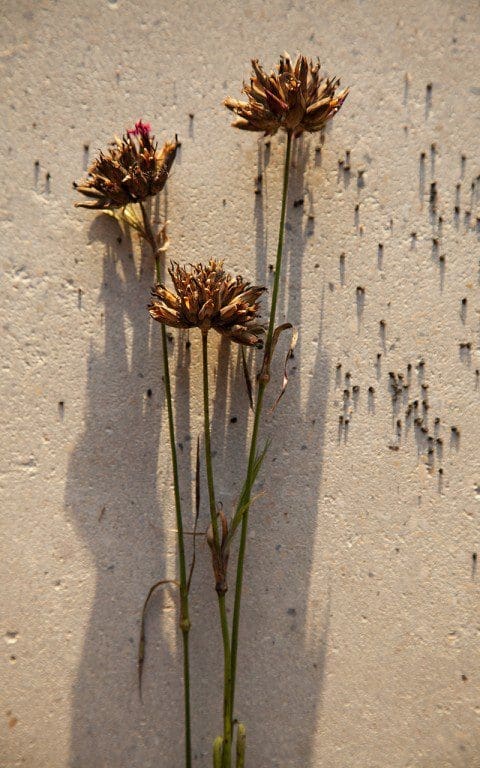

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018 We are on holiday for two weeks and so leave you with some recent images of the garden to keep you going until we return.

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Selinum wallichianum, Sanguisorba ‘Red Thunder’, Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ and Anemone x hybrida ‘Honorine Jobert’

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Amicia zygomera and Agastache nepetoides

Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Little Henry’ and Agastache nepetoides

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Aster umbellatus, Persicaria amplexicaule ‘Blackfield’, Salvia ‘Jezebel’ and foliage of Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’, Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Persicaria amplexicaule ‘September Spires’

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa columbaria ssp. ochroleuca

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Hesperantha coccinea ‘Major’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Anemone hupehensis var. japonica ‘Splendens’ and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Colchicum speciosum ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Chasmanthium latifolium and Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 October 2018

Grasses were always going to be an important part of the garden. They make the link to the meadows and fray the boundary, so it is hard to tell where garden begins and ends. On our windy hillside, they also help in capturing this element, each one describing it in a slightly different way. The Pennisetum macrourum have been our weather-vanes since they claimed the centre of the garden in August. Moving like seaweed in a rock pool on a gentle day, they have tossed and turned when the wind has been up. The panicum, in contrast, have moved as one so that the whole garden appears to sway or shudder with the weather.

Though the pennisetum took centre stage and needed the space to rise head and shoulders above their companions, they are complemented by a matrix of grasses that run throughout the planting and help pull it together from midsummer onwards. Choosing which grasses would be right for the feeling here was an important exercise and the grass trial in the stock beds helped reveal their differences. At one end of the spectrum, and most ornamental in their feeling, were the miscanthus.

Clumping strongly and registering as definitely as a shrub in terms of volume, I knew I wanted a few for their sultry first flowers and then the silvering, late-season plumage. It soon became clear that they would need to be used judiciously, for their exotic presence was at odds with the link I wanted to make to the landscape here. At the other the end of the spectrum were the deschampsia and the melica, native grasses which we have here in the damp, open glades in the woodland. We have used selections of both and they have helped ground things, to tie down the garden plants which emerge amongst them.

Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’

Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’

Molinia arundinacea ssp. caerulea ‘Transparent’

Molinia arundinacea ssp. caerulea ‘Transparent’

Falling between to two ends of the shifting scale, we experimented with a range of genus to find the grasses that would provide the gauziness I wanted between the flowering perennials. As it is easy to have too many materials competing when choosing your building blocks for hard landscaping, so it is all too easy to have too many grasses together. Though subtle, each have their own function and I knew I couldn’t allow more than three to register together in any one place. Tall, arching Molinia caerulea ssp. arundinacea ‘Transparent’ that is tall enough to walk through and yet not be overwhelmed by would be the key plant at the intersection of paths. The fierce uprights of Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, scoring thunderous verticals early in the season and then bleaching to longstanding parchment yellow, would need to be given its own place too in the milking barn yard. I needed something subtler and less defined as their complement in the main garden.

Our free-draining ground and sunny, open position has proved to be perfect for cultivars of Panicum virgatum or the Switch Grass of American grass prairies. We tried several and soon found that, as late season grasses, they need room around their crowns early in the season if they are not to be overwhelmed. Late to come to life, often just showing green when the deschampsia are already flushed and shimmering with new growth, it is easy to overlook their importance from midsummer onwards. I knew from growing them before that they like to be kept lean and are prone to being less self-supporting if grown too ‘soft’ or without enough light, but here they have proven to be perfect. Bolting from reliably clump-forming rosettes, each plant will stay in its place and can be relied upon to ascend into its own space before filling out with a clouding inflorescence.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. The original stock plant is in the centre.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. The original stock plant is in the centre.

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

I tried several and, with the luxury of having the space to do so, some proved better than others. The largest and most dramatic is surely ‘Cloud Nine’. My eldest plant, the original, remains in the position of the old stock bed and the garden and younger companions were planted to ground it. This was, in part, due to it already being in the right place, for I needed a strong presence here where I’d decided not to have shrubs and they have helped with their height to frame the grass path that runs between them and the hedge along the lane. By the time the stock beds were dismantled we were pleased not to have to move it, because the clump is now hefty, and a two man job to lift and move it.

I first saw this selection in Piet Oudolf’s stock beds several years ago, where it stood head and shoulders above his lofty frame. Scaled up in all its parts from most other selections, the silvery-grey leaf blades are wider than most panicum and very definite in their presence. Standing at chest height in August before showing any sign of flower, it is the strongest of the tribe. Now, in early autumn, its pale panicles of flower have filled it out further, broadening the earlier bolt of foliage. If it was a firework in a firework display of panicum, it would surely be the last, the scene-stealer that has you gasping audibly. I like it too for the way it pales as it dies and it stands reliably through winter to arrest low light and make a skeletal garden flare that is paler in dry weather and cinnamon when wet.

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

Panicum virgatum ‘Rehbraun’

I have three other panicum in the garden, which are entirely different in their scale and presence. Though it has proven to be larger than anticipated in our hearty ground and will need moving about in the spring to get the planting just right, I am pleased to have selected ‘Rehbraun’. Calm, green foliage rises to about a metre before starting to colour burgundy in late summer. The base of redness is then eclipsed by a mist of mahogany flower, which when planted in groups, moves as one in the breeze. I have it as a dark backdrop to creamy Ageratina altissima ‘Braunlaub’ (main image) and Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, which are wonderful as pinpricks of brightness held in its suspension. It is easily 1.2 metres tall here and, weighed down by rain, it can splay, and I have found that several are too close to the path, but I like it and will find them a place deeper within the borders.

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’

Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’

Though it has not done as well for me here – it may well be that it is a selection from a drier part of the States – ‘Heiliger Hain’ has been beautiful. Silvery and fine, the leaf tips colour red early in summer and are strongly blood red by this point in the season. It is small, no more than 80cm tall when in flower, and so I have given it room to rise above Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’ and the delicate Succissella inflexa. Similar in character, though better and stronger, is ‘Shenandoah’ which I have drawn through most of the upper part of the garden. Blue-grey in appearance as it rises up in the first half of summer, it begins to colour in late August, bronze-red becoming copper-orange as it moves into autumn. Neil Lucas of Knoll Gardens says it has the best autumn colour of all panicum. It also stands well in winter to cover for neighbours that have less stamina. Where in the right place, with plenty of light and no competition at the base whilst it is awakening, it is proving to be brilliant and will be the segue from the summer garden, slowly making its presence felt above an undercurrent of asters to finally eclipse everything in a last November burn.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 29 September 2018

It has been an extraordinary run. Day after day, it seems, of clear sky and sunlight. I have been up early at five, before the sun has broken over the hill, to catch the awakening. Armed with tea, if I have been patient enough to make myself one before venturing out, my walk takes me to the saddle which rolls over into the garden between our little barn and the house. From here, with the house behind me and the garden beyond, I can take it all in before beginning my circuit of inspection. It is impossible to look at everything, as there are daily changes and you need to be here every day to witness them, but I like to try to complete one lap before the light fingers its way over the hedge. Silently, one shaft at a time, catching the tallest plants first, illuminating clouds of thalictrum and making spears of digitalis surrounded in deep shadow. It is spellbinding. You have to stop for a moment before the light floods in completely as, when you do, you are absolutely there, held in these precious few minutes of perfection.

Now that the planting is ‘finished’, the experience of being in the garden is altogether different. Exactly a year ago the two lower beds were just a few months old and they held our full attention in their infancy. The delight in the new eclipsed all else as the ground started to become what we wanted it to be and not what we had been waiting for during the endless churn of construction. We saw beyond the emptiness of the centre of the garden, which was still waiting to be planted in the autumn. The ideas for this remaining area were still forming, but this year, for the first time, we have something that is beginning to feel complete.

Looking down the central path from the saddle

Looking down the central path from the saddle

The view from the barn verandah

The view from the barn verandah

Of course, a garden is never complete. One of the joys of making and tending one is in the process of working towards a vision, but today, and despite the fact that I am already planning adjustments, I am very happy with where we are. The paths lead through growth to both sides where last year one side gave way to naked ground, and the planting spans the entire canvas provided by the beds. You can feel the volume and the shift in the daily change all around you. It has suddenly become an immersive experience.

An architect I am collaborating with came to see the garden recently and asked immediately, and in analytical fashion, if there was a system to the apparent informality. It was good to have to explain myself and, in doing so without the headset of my detailed, daily inspection, I could express the thinking quite clearly. Working from the outside in was the appropriate place to start, as the past six years has all been about understanding how we sit in the surrounding landscape. So the outer orbit of the cultivated garden has links to the beyond. The Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ on the perimeter skip and jump to join the froth of meadowsweet that has foamed this last fortnight along the descent of the ditch. They form a frayed edge to the garden, rather than the line and division created by a hedge, so that there is flow for the eye between the two worlds. From the outside the willows screen and filter the complexity and colour of the planting on the inside. From within the garden they also connect texturally to the old crack willow, our largest tree, on the far side of the ditch.

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

The far end of the garden which was planted in Spring 2017

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Knautia macedonica, Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, Cirsium canum and Verbena macdougallii ‘Lavender Spires’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Thalictrum ‘Elin’ above Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Eupatorium fistulosum f. albidum ‘Ivory Towers’ emerging through Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

Asclepias incarnata, Echinops sphaerocephalus ‘Arctic Glow’, Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ and Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

This first outer ripple of the garden is modulated. It is calm and delicate due to the undercurrent of the Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Goldtau’, but strong in its simplicity. From a distance colours are smoky mauves, deep pinks and recessive blues, although closer up it is enlivened by the shock of lime green euphorbia, and magenta Geranium psilostemon and Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. Ascending plants such as thalictrum, eupatorium and, later, vernonia, rise tall through the grasses so that the drop of the land is compensated for. These key plants, the ones your eye goes to for their structure, are pulled together by a veil of sanguisorba which allows any strong colour that bolts through their gauzy thimbles to be tempered. Overall the texture of the planting is fine and semi-transparent, so as to blend with the texture of the meadows beyond.

The new planting, the inner ripple that comes closer but not quite up to the house, is the area that was planted last autumn. This is altogether more complex, with stronger, brighter colour so that your eye is held close before being allowed to drift out over the softer colour below. The plants are also more ‘ornamental’ – the outer ripple being their buffer and the house close-by their sanctuary. A little grove of Paeonia delavayi forms an informal gateway as you drop from the saddle onto the central path while, further down the slope a Heptacodium miconioides will eventually form an arch over the steps down to the verandah, where the old hollies stand close by the barn. In time I am hoping this area will benefit from the shade and will one day allow me to plant the things I miss here that like the cool. The black mulberry, planted in the upper stockbeds when we first arrived here, has retained its original position, and is now casting shade of its own. Enough for a pool of early pulmonaria and Tellima grandiflora ‘Purpurteppich’, the best and far better than the ‘Purpurea’ selection. It too has deep, coppery leaves, but the darkness runs up the stems to set off the lime-green bells.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’, Euphorbia wallichii and Thalictrum ‘Elin’

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

Lilium pardalinum, Geranium psilostemon and Euphorbia cornigera

The newly planted central area

The newly planted central area

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Kniphofia rufa, Eryngium agavifolium and Digitalis ferruginea

Eryngium eburneum

Eryngium eburneum

There is little shade anywhere else and the higher up the site you go the drier it gets as the soil gets thinner. This is reflected in a palette of silvers and reds with plants that are adapted to the drier conditions. I am having to make shade here with tall perennials such as Aster umbellatus so that the Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which run through the upper bed, do not scorch. Where the soil gets deeper again at the intersection of paths, a stand of Panicum virgatum ’Cloud Nine’ screens this strong colour so it can segue into the violets, purples and blues in the beds below. I have picked up the reds much further down into the garden with fiery Lilium pardalinum. They didn’t flower last year and have not grown as tall as they did in the shelter of our Peckham garden, but standing at shoulder height, they still pack the punch I need.

The central bed, and my favourite at the moment, is detailed more intensely, with finer-leaved plants and elegant spearing forms that rise up vertically so that your eye moves between them easily. Again a lime green undercurrent of Euphorbia ceratocarpa provides a pillowing link throughout and a constant from which the verticals emerge as individuals. Flowering perennials are predominantly white, yellow and brown, with a link made to the hot colours of the upper bed with an undercurrent of pulsating red Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’. Though just in their first summer, the Eryngium agavifolium and Eryngium eburneum are already providing the architecture, while the tan spires of Digitalis ferruginea, although short-lived, are reliable in their uprightness.

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Echinacea pallida ‘Hula Dancer’ and Eryngium agavifolium

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Digitalis ferruginea, Eryngium agavifolium and E. eburneum

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

Hemerocallis ochroleuca var. citrina, Digitalis ferruginea, Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ and Scabiosa ochroleuca

It has been good to have had the pause between planting up the outer beds in spring last year, before planting the central and upper areas in the autumn. We are now seeing the whole garden for the first time as well as the softness and bulk of last year’s planting against the refinement and intensity of the new inner section. Constant looking and responding to how things are doing here is helping this new area to sit, and for it to express its rhythms and moments of surprise.

I am taking note with a critical eye. Will Achillea ‘Mondpagode’ have a stay of execution now that it is protected in the middle of the bed ? Last year, planted by the path, it toppled and split in the slightest wind. Where are the Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Henry Eilers’ and, if they have failed, how will I get them in again next year when everything will be so much bigger ? Have I put too many plants together that come too early ? Too much Cenolophium denudatum, perhaps ? How can this be remedied ? Later flowering asters and perhaps grasses where I need some later gauziness. Will the Dahlia coccinea var. palmeri grow strongly enough to provide a highlight above the cenolophium and, if not, where should I put them instead ? The season will soon tell me. The looking and the questioning keep things moving and ensure that the garden will never be complete.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 7 July 2018

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage