The elder is spilling from the hedgerows, creamy, heavy with flower and weighted by a deluge of June rain. This is their month and we can see them marching up the valley and foaming from the edges of the copses where they are happy to seed into shadow, but prefer to push out into the sun.

Elder is fast. Their shiny black berries, which are some of the first to be gorged on by birds in the autumn, are deposited wherever there has been a perch. I find them here under the woody shrubs in the garden and where there has been a perennial left standing that has provided a place for a pause. We even have a quite mature elder that has found its way into a humus laden crack high up in an old ash pollard to prove their ease in finding a niche.

They look innocent as seedlings and are easily weeded but if you miss one you will have a sturdy little plant that will jump up and out into the light in its second year and in the third already be demanding space that might have been promised to something else. They go on in life living fast and hungry and, if you have them in a hedge and leave it uncut, they will create a gap there by simply outcompeting their neighbours. They age quickly and fall apart with topweight, so opening up a wedge. It is into these gaps that you will find brambles seeding and then a whole new wave of succession.

I must admit to removing them where I have been repairing the hedges so that I can replace them with hedging plants that retain a more measured growth cycle. Hazel, hawthorn, dogwood, viburnum and eglantine rose. It is bad luck I know, but where I have done it I now have hedges that are opaque in winter and layered from the bottom up with three plants replacing the weight of the interloper. A cut piece of elder wood reveals why its old Anglo Saxon name aeld (meaning fire) was given, because the hollow stems were used to blow air directly into the heart of a fire. Although it is also unlucky to bring elder inside, I suppose there must be room for exceptions.

We are lucky enough to have room to let a number of elders have their head here and, only when June weather allows, we steep them and make cordial, since the flowers need to be dry when harvesting. Their heady, sweet perfume is completely distinctive and reminiscent of this time later in the year. A moment of fecund growth and dampness still in a young summer. Where we have let a hedge grow out to make a bat corridor on our high field, a plant that is easy to harvest is paired very beautifully with wild rose, the cream and pink heightened for their company. The coupling has been inspiration for a cordial that Huw is making this week with some of the first roses as a means of capturing this moment.

Where I want to make a quick impression in a garden that needs something evocative of a wilder place, or indeed to segue from garden to landscape, I will often use the cut-leaved Sambucus nigra f. laciniata. This is a lovely plant, strong but lighter on its feet than the straight species and already tall and making an impression in year two. More ornamental selections have given us good dark-leaved forms with cut foliage that are exquisite and easily used. The filigree of ‘Black Lace’ and ‘Eva’ are better I think than ‘Black Beauty’, which has a more simple leaf that can look heavy. The darkness in their genes spawns flowers that are as pink as the species is cream and are a strong influence in the June garden. I haven’t grown the yellow cut-leaved ‘Golden Tower’ which is said to be smaller in stature, but it could be nice in a little shadow to give the impression of artificial sunlight when June days are bringing us (welcome) rain and grey skies.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photos: Huw Morgan

Published 15 June 2019

Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my earliest inspiration were the roses growing on the pathway leading up to our childhood house. That scent has stayed with me forever. The rose is a very powerful plant, it triggers so many memories. Like a form of time travel, it has taken me to some very magical times and places, it has been hugely influential.

Then I was inspired by learning about distilling plants with an eau de vie distiller in Alsace and connecting with herbalists such as Peter Jackson Main, Peter Conway, the work of Barbara Griggs and for sure the writing of Stephen Harrod Buhner. I urge everyone to read his book The Lost Language of Plants.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Photo: Susan Bell

You are a qualified Phytotherapist. Can you explain what that means and what the training involves?

It’s a posh term for a herbalist, to make us sound more professional. It means somebody who works with plants to heal and nurture people. We introduce nature and look at ways in which plants can help support disease, illness or just enrich people’s lives.

I trained with many naturopaths, nutritionists, herbalists and plant workers on shorter courses and then went into a full time BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Westminster. It took four years of full time training, but some of the most valuable training is spending time with the plants themselves. They can teach you a great deal.

Tell us about the range of products you produce, and the process you went through to develop them.

It all started as I was unhappy with the quality of the herbs & spices in many herbal teas and commercial spice ranges. There was (is) a distinct lack of relationship between people and the plants that they are drinking or eating. Supermarkets are littered with herbs in tea bags and boxes, but you don’t see the plants or engage with them enough. You don’t know where they are from, when they were harvested, who harvested them, you can’t even see the plants. So I wanted to create a range of plant products where you could really engage with the plant itself, on a very basic level by looking at and identifying it, drinking its qualities. It’s about engaging with and respecting nature really. I want people to see the love and hard work (from both the plant and the people producing them) that goes into nurturing, growing, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs.

We take plants for granted most of the time. Just take black pepper for example. In almost all households it is just a commodity. It’s just not celebrated enough. It’s a sensational plant, with brilliant flavour. Just take a good quality black peppercorn and place it in your mouth and eat it. Taste it fully and consider its qualities. Phenomenal.

We really want people to engage with the nature that they are drinking, eating and ingesting. All of our plants are harvested in that growing year, we know when they were harvested and by whom. We make our infusions, waters and bitters in tiny batches. It’s all created by hand with lots of care using the most vibrant plant material possible.

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

Our aromatic waters (non-alcoholic distillations of plants) were sourced from two distillers in the UK and India, although we have since stopped working with them as we are now distilling everything ourselves. There will be some very special distillates available in 2018 as we are currently working on polypharmic distillations, distilling lots of different plants at the same time. There is a natural synergy between plants in the wild and it’s always interesting to see which plants like to grow together, for example nettle & cleavers. We are trying to capture this synergy and relationship in the form of a distillation.

We distil plants in traditional copper alembic stills (main image – photo by Susan Bell) to use as a flavouring for food and drinks and as ingredients for natural skin care. We are just starting to use CO² extraction, which produces the most beautiful and vibrant oils. We also work with co-operatives in Southern India and Sri Lanka who supply us with beautiful vibrant spices. Again it is crucial that we know who harvested the plants, where and when. We visit the growers on their tiny holdings – when I say tiny they are really tiny, 1 hectare and less – and they cannot afford organic certification, so that’s where the co-operative comes in, to help give the growers the sales platform and access to people like us.

The bitters are remedies and recipes that I had been using in practice and for drinks creation for years. They cover all of my inspirations, so there is an English-based blend with 20 herbs grown here, an Indian blend with spices like cinnamon, turmeric and one of my favourite bitter herbs, Andrographis, and a Chinese blend with Chinese herbs such as Schisandra paired with a beautiful rock oolong tea from our dear friends at Postcard Teas. We wanted to share these formulas with everyone.

From where and how do you source your ingredients?

The herbs we use are mostly grown, nurtured, harvested and dried by a wonderful grower called Diane Anderson who has a smallholding in Oxted, Surrey. Diane was one of my teachers at University. She was an amazing resource and she used to come into the dispensary with the most beautiful dried herbs. Seeing these wonderful dried herbs was also an inspiration to start blending infusions.

We also work with a biodynamic plantation in Somerset, we grow a few things ourselves and for the more exotic plants, as mentioned before, we source from our friends in Southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cardamom

Cardamom

Turmeric

Turmeric

Can you explain how the bitters and herbal waters you produce might be used?

I’m not allowed to talk too much about the health benefits of our products, so broadly speaking their purpose is really to enhance and envigorate drinks and dishes and to give pleasure. The bitters are amazing just with water, or fresh juice, pre- and post-prandial, to stimulate digestive function and assimilate some of the metabolites from your meal. The aromatic waters are so diverse, I use them every day in a glass of water, sprayed directly on my face as a toner (rose), in salad dressings (rosemary & thyme are particularly good), to create cocktails with and without alcohol. They are amazing.

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

Can you tell us something of the therapeutic effects of some of your key ingredients?

Plants have endless therapeutic qualities on so many levels, physically, spiritually, emotionally, and I think it’s important that you are ingesting some good quality organic plants every day. I don’t want to say as part of a routine as that sounds boring, but use them prophylactically as a preventative. Have fun with plants, get to know them, enjoy their nature, enjoy their brilliance, it’s so rewarding for health and happiness.

The herbs we use and work with are packed full of complex secondary metabolites, diverse plant chemicals (phytochemicals) produced by the plants which enable the plants to interact with their environment. These phytochemicals have a wide range of functions, including protection from herbivores, to fight against infections and to attract pollinators such as bees and other insects. The plant’s secondary metabolites include constituents such as tannins, aromatic oils, alkaloids, resins and steroids. It is these chemicals that not only carry a raft of potential health benefits for us, but also offer a huge palette of flavours, textures and aromas to create delicious food and drinks.

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

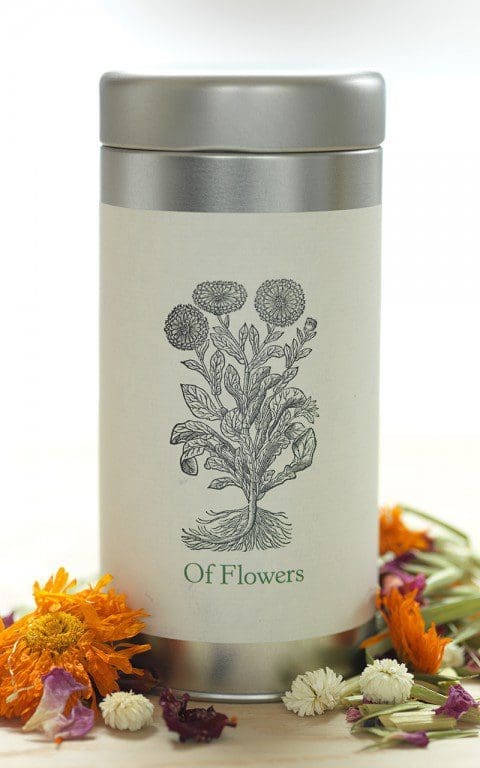

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

You have a book coming out in the new year. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Super exciting, yes. It’s a book on my work really. I talk about my inspirations, some of the plants that I work with, when and how to harvest them and then how you can work with those plants to create dynamic and delicious botanical drinks. I talk about distillation, extraction methods, drying and processing the plants and then there are over fifty recipes, all without alcohol.

Would you share a recipe with us that readers can try at home?

Sure. I’m drinking a lot of sage right now so here is a simple recipe with sage including a quote from John Gerard, whose work we have been greatly inspired by, he wrote (or collated and published) the seminal text The Herball or Generall historie of plantes, 1597.

THE WISE ONE

‘Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members’. John Gerard 1545 – 1612.

Photo: Susan Bell

Photo: Susan Bell

This is a contemporary take on a classic sage preparation to produce a cooling, blood cleansing formula, which makes for a sensational afternoon tipple.

Plants & Ingredients

Sage Salvia officinalis

Lemon Citrus limon

Sugar Saccharum officinarum

Water

Recipe

15g fresh sage

4 lemons

500ml hot water

75ml lemon & sage sherbet (see below)

100g sugar

Method

Boil the water, then pour over 10g of sage into a pot with a lid. Infuse with the lid on for 30 minutes before straining into another jug or decanter. Peel 1 of the lemons and keep the zest. Add the juice of that lemon and the sherbet to the decanter and stir until dissolved. Keep the jug or decanter in the fridge to chill and serve once cold.

Serve in a wine glass with the remaining twist of lemon and fresh sage leaves

For the Sherbet

Peel the remaining 3 lemons, then put the zests in a container with the sugar and the remaining 5g of sage. Press the zests with the sugar and sage for a minute or so, then juice the lemons and stir the juice into the sugar mixture. Seal and leave to infuse overnight, or for at least 6 hours. Stir, strain and bottle. This will keep refrigerated for at least 1 month and can be enjoyed with still and sparkling water.

The Herball’s Guide to Botanical Drinks: A Compendium of plant-based potions to Energise, Cleanse, Restore, Boost Sleep and Lift the Heart by Michael Isted, photography by Susan Bell, will be published by Jacqui Small in February 2018. Pre-order here.

Twitter: @TheHerball

Instagram: theherball

Interview: Huw Morgan/All other photographs: Laura Knox

Published 30 September 2017

One of the goals we set ourselves when we started Dig Delve was for the writing to be as current as possible. A piece on crabapples the week they are in full bloom, a report of a garden visit made just a couple of weeks previously, and recipes using the best from the kitchen garden and hedgerows as they come into season. Many of the pieces are written the day before publication, so this ambition is not without its challenges, since Dan is often travelling for work, we need to have holidays, and sometimes other life events simply have to take precedence.

Dan has been up north this week. Firstly visiting the new RHS Chatsworth Flower Show and then on to Lowther Castle in Cumbria, where they are celebrating their official opening this weekend. So it was down to me to come up with this week’s piece.

However, like most of the country, I was up into the small hours of Friday morning watching the election coverage with bated breath. The consequent late morning start, with the accompanying time required to get a handle on what was happening in parliament, meant that I had to think on my feet to come up with a recipe for today’s issue.

I had originally thought to make a gooseberry and elderflower ice. Whether ice cream or sorbet I hadn’t decided, but, after half an hour Facetiming a friend in New Zealand who had called for an election update, it was clear that I wasn’t going to have the time to faff around with sugar syrups or custards or the freezing required afterwards. I needed something simple and immediate.

Earlier in the week I had got my first batch of elderflower cordial going and it was ready to strain and bottle. I try and make a large batch every year, but have been foiled for the past two by a combination of constant wet weather and being away in June. The recent clear, warm weather meant that, for the first time in a while I have been able to pick enough to be able to replenish our supplies.

It is essential to pick the flowers on a warm day when they are dry, and to only pick the freshest ones that have just opened and are purest in colour. If you live in a city don’t pick flowers near main roads (when we lived in Peckham I used to get my supplies from nearby Nunhead Cemetery). Don’t, whatever you do, wash the flowers, as you will wash away the pollen which gives the drink most of its flavour. For the same reason I don’t even shake the flowers before using, as many recipes suggest. Unless you are squeamish any small insects get strained out prior to bottling.

I can never get enough of the flavour of elderflower. Its floral taste announces summer. Sparkling elderflower cordial is the most refreshing way to slake your thirst during a hot afternoon’s gardening. Although I have found that a scant teaspoon of cider vinegar added to a glass is the most refreshing of all. Like orange blossom’s more demure, earthy cousin elderflower pairs well with any number of fruits, from strawberries to rhubarb, pears, raspberries, grapes and even grapefruit. It also works with gently flavoured vegetables that allow its floral notes to shine. A teaspoon or two of cordial adds fragrancy to a vinaigrette for a white chicory and goats cheese salad. A pickled salad of very finely sliced cucumber macerated in a dressing made with cordial, honey and, again, cider vinegar, and finished with poppy seeds and elderflowers, makes a sophisticated partner for poached trout or salmon.

Yesterday’s time shortage meant that I was thrown back on the reliable combination of elderflower and gooseberry, which crops up in a number of desserts I regularly make, including the unavoidable fool, a green summer pudding and a baked egg custard tart. The gooseberries aren’t quite ripe when the elder blooms, but for this drink you want the refreshing sharpness of the younger fruit.

This celebratory aperitif is a version of a Bellini where peach puree is replaced with gooseberries and a splash of elderflower cordial. I may have only had bad ones, but have always found peach Bellinis to be a little sickly. Here the combination of tart green fruit and scented flower create a drink with a distinct muscat flavour, which is dry, fragrant and deliciously quenching on a hot summer’s day. To ensure the best result, it is vital that everything, including the glasses, is ice cold before you make them.

First is the recipe I use for homemade cordial, but you could use a good quality shop-bought one.

Elderflower Cordial

Ingredients

Makes about 1.5 litres

30 elderflower heads

1kg white sugar

1 litre water

2 lemons, chopped

1 orange, chopped

2 teaspoons citric acid

¼ crushed Campden tablet (optional)

Put the sugar and water in a saucepan and bring to the boil. Stir and ensure the sugar is completely dissolved. Take off the heat and stir in the citric acid until dissolved.

Put the elderflowers and chopped citrus fruit into a sterilised plastic or glass lidded container large enough to take all of the ingredients. Pour over the hot sugar syrup. Put the lid on the container and leave in a cool dark place for 48 – 72 hours.

Strain the cordial through a fine muslin or tea towel that has first been sterilised with boiling water. Finely crush the Campden tablet and add it to the cordial. Stir until dissolved.

Using a funnel pour the cordial into sterilised bottles. Fasten the lid and store in a cool, dark place.

The Campden tablet (potassium or sodium metabisulfite) prevents the cordial from developing wild yeasts and bacteria which would cause it to ferment, and means that it keeps almost indefinitely. If you prefer not to use them the cordial will keep for 2-3 months, or longer if refrigerated.

Gooseberry ‘Hinnomaki Green’

Gooseberry ‘Hinnomaki Green’

Gooseberry & Elderflower Bellini

Ingredients

Makes 6

100g green gooseberries

Elderflower cordial, chilled

1 bottle dry prosecco

Put the gooseberries in a saucepan with a splash of water. Put the lid on and cook over a low heat for about 10 minutes until the fruit has completely collapsed and given up its juice. Press the fruit through a sieve. You should have about 80ml of purée. Discard the seeds and skin. Put the purée into a covered container, then into the fridge until well chilled.

To make the drinks, take six champagne flutes or narrow tumblers that have been in the freezer for at least twenty minutes. Put two teaspoons of gooseberry purée and two teaspoons of elderflower cordial in the bottom of each glass. Slowly top up with very cold prosecco.

Decorate with a few elderflowers and raise a toast!

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 10 June 2017

At this time of year there is always more fruit than it is possible to process and preserve. This has been a small torture in previous years but, gradually, we are coming to terms with the necessary waste and, whenever possible, we give fruit away to neighbours or bring baskets of windfalls back to the office in London. As the orchard grows in stature we plan to offer the pickings that we can’t use to local restaurants, and start juicing on a more regular basis.

Every autumn I make a number of preserves, both to stock the winter pantry and to provide Christmas presents for friends and neighbours. Last year it was bottles of pumpkin ketchup and jars of wild apple and rosemary jelly, the year before damson cheese and homemade crème de cassis and crème de mûres. This year the crabapples have been their most productive since they were planted 6 years ago, groaning under the weight of bright red fruits, and I couldn’t countenance leaving them all for the birds. I have always been a little daunted by the prospect of harvesting crabapples and it does take longer to harvest enough compared to regular apples. However, with a sharp pair of secateurs to hand, it only took me 30 minutes to collect 3 kilos, which is plenty for a good batch of jelly, producing plenty to give away.

It is difficult to give exact quantities for jellies, as the amount of sugar required is completely dependent on the amount of juice you can extract. The 3 kilos of fruit I collected produced about 6 kilos of jelly. Due to their high pectin content crabapples (and wild apples) make the best base fruit for other types of foraged jellies, as long as crabapples make up no less than half the combined weight of your fruit. You can mix them with brambles, haws, sorbs, sloes, rosehips and elderberries to make a mixed hedgerow jelly, or with any of these other fruits alone to produce a jelly that tastes more purely of the partner ingredient. I used the fruit of Malus hupehensis, which produces a vibrant red jelly. Less strongly coloured fruit, such as the yellow Malus ‘Evereste’, produce an amber jelly.

Adding spice in some form allows this jelly to cross over from a topping for bread or toast to an accompaniment to game, cold meats and cheeses. Bay and a little clove make this a good partner to cold ham, although rosemary and juniper would make it a good pairing with game. Add a few spoonfuls to the gravy from a braised pheasant or partridge before serving

Ingredients

Crabapples

Granulated sugar

Water

Bay leaves

Cloves

Method

Wash the fruit and chop coarsely. This can be done in a food processor. Put into a preserving pan and just cover with water. Add one bay leaf and 3 cloves per kilo of fruit.

Put on a low heat and slowly bring to a simmer. Cook gently until the fruit is soft and pulpy.

Allow the fruit pulp to cool slightly before pouring into a scalded muslin jelly bag. Allow to strain for at least 6 hours, or overnight. Do not squeeze the pulp or the jelly will be cloudy.

Measure the juice and put into a clean preserving pan and heat gently. Once the juice is hot add 450g of sugar for every 600ml of juice. Stir until the sugar is dissolved, then bring to the boil, skimming off the scum that appears on the surface. Allow to boil for 10 minutes without stirring.

While this is happening put a small plate into the freezer. After 10 minutes of boiling test the jelly for setting by dropping a little of it onto the cold plate and returning to the fridge for a minute. The jelly is set when the surface wrinkles when pushed with a finger. If it isn’t set after 10 minutes then return to the boil and re-test every 3-5 minutes.

Once setting point has been reached allow the jelly to settle off the heat for a couple of minutes. Reskim again to remove all scum from the surface before pouring the jelly into hot, sterilised jam jars. Cover with waxed paper and seal with clean lids.

Recipe & photography: Huw Morgan

It has been a good year for the hawthorn. It is foaming still up the hedge lines and cascading out of the woods above the stream at the bottom of the hill. We have gravitated there in the evening sunshine to stand at the bottom of the slope and marvel. The trees have been drawn up tall and slender and the froth of creamy flowers brightening the shadows of the newly sprung wood. At the margins of the wood, their favoured place, the branches push out wide and low, a hum of insects enticed by an uncountable sum of flower.The hawthorns saw the apples come and go and now they are starting to dim, it is summer. Why they were as weighted so heavily with flower this year I do not know, but it is the best they have been since we arrived here and I am pleased I have planted them as plentifully.

Haw, May, Quick, Quickset; hawthorn is a tree surrounded in folklore. Cut one and you will be plagued by fairies, but turn the milk with a twig before churning and you will protect the cheese from bewitchment. According to Teutonic legend, the tree originated from a bolt of lightning, which is why the wood was used on funeral pyres. The power of the sacred fire was sure to ferry your spirit to heaven.

In ancient rituals the hawthorn symbolised the renewal of nature and fertility, which often made it the choice for a maypole at Beltane. The wood itself is one of the hardest and often used for fine engraving and the young leaves are surprisingly delicious in a salad, with a fresh nutty taste.

The flowers, however, smell both sweet and stale. Some find this unpleasant, but to my nose it is just a country smell, which attracts flies and insects that lay their eggs on decaying animal matter. Crataegus is well known for the diversity of species that live within the thorny cage of its branches or on the bark or the foliage so, despite the superstition around it, it is a mainstay of the countryside.

I have relied upon it as the greater component when replanting my native mixed hedges. It is called Quick with good reason and the hedges that I planted to gap up our broken boundaries five years ago are already six feet high, thick and impenetrable. I wonder how elderly some of the thorns are in the oldest of the hedges here. It is estimated that 200,000 miles of them were planted between 1750 and 1850 as a result of the Enclosure Acts. During this time there were nurseries committed to growing the hawthorn in quantity to meet the demand, and making a small fortune from the supply.

If you leave your hedges and cut them year on, year off, the hawthorn flowers and fruits more heavily. Leave a tree free-standing and it will be reliably heavy with dark red berry in October. The berry is the way to propagate. I leave them for as long as I dare before taking my share, for the birds will suddenly strip a tree when the fruits ripen. The digestive juices of birds help to break the inbuilt dormancy of the seed, but you can simulate this by leaving the berries to ferment for a week in water before lining out in a drill in the garden. Some may germinate the following year after the action of frost has worked its magic, but two years of stratification may be required before you get a full row to germinate. Within a year of germinating you will have young plants a foot or so tall, in two whips ready to make a hedge. Or the beginnings of a maypole.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The green sauce in this recipe is not the well known mediterranean salsa verde, but Grüne Sosse, a speciality of Frankfurt introduced to me by our friend Ariane, a native of the city, and a neighbour in Bonnington Square for many years. It is traditionally served with asparagus of the forced white variety, which is particularly prized in Germany, where Spargelfesten are held in its honour every spring. Although green sauce made from a variety of herbs can be found in German restaurants all year round, it is only in early spring that the truly authentic sauce can be made, when the herbs required are coming into their prime and the paper packages of them required to make it are found in farmer’s markets, together with the white asparagus which it traditionally accompanies.

Genuine Grüne Sosse requires seven specific herbs; sorrel, chervil, chives, parsley, salad burnet, cress and borage. However, it is seldom that any of us have access to all of these herbs, and so substitutions can be made. The crucial thing is to ensure a good balance of flavours, with the requisite amount of sourness, freshness, bitterness and spice. There is no hard and fast rule about how much of each herb to use, but a rule of thumb is that no one herb should make up more than 30% of the bulk. When possible I try to get a fairly even balance between all of them, but you should adjust to taste and to what is available.

From left to right: borage, wild chervil or cow parsley, salad burnet, wild onion, watercress, sorrel, parsley

Since it is so plentiful in our fields I use wild sorrel (Rumex acetosa), which I suspect is what the authentic recipe calls for, however you can replace this with the more usually grown French or garden sorrel (Rumex scutatus). If neither of these are available you could use young chard or spinach leaves and an extra squeeze or two of lemon juice.

When it is available I use wild chervil instead of cultivated. Otherwise known as cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), it is perfect to pick right now, and can be substituted for garden chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium) in salads or sauces for chicken and fish. If you are an inexperienced forager you must be extremely careful not to mistake poisonous hemlock for cow parsley. Use a good field identification guide (Miles Irving’s The Forager Handbook and Roger Phillips’ Wild Food are invaluable) and, if in doubt, do not pick it.

In place of chives I use wild onion (Allium vineale) from the fields, being careful to pick only the youngest quills, as the older ones are tough. The cress can be replaced with watercress, rocket or even nasturtium leaves, to provide the peppery note. And, from the hedgerows, I have also used the leaves of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), young dandelion leaves and even nettle tops, when the other herbs are hard to come by.

The salad burnet and borage both impart a distinctive cucumber flavour which it is not possible to replicate with other herbs and which is particular to this sauce. When unavailable I have used peeled and finely grated cucumber in their place. Salt it and squeeze the juice from it before incorporating, to prevent it diluting or curdling the sauce.

It is also possible to make up the quantities with more easily available herbs such as dill, fennel, tarragon or mint but, with their pronounced flavours, these should all be used in moderation or they will overwhelm the flavour.

This sauce is also traditionally served with boiled new potatoes and halved hard boiled eggs, or as an accompaniment to boiled beef or poached fish.

Clockwise from top left: salad burnet, watercress, sorrel, parsley, wild onion, borage, wild chervil

Ingredients

150g mixed green herbs

250g sour cream or quark

125g yogurt

2 hard-boiled eggs

3 tablespoons lemon juice

sea salt

7-8 spears of asparagus per person

Serves 4

Method

Wash the herbs. Put them in a salad spinner and then dry on a tea towel or paper towel.

Remove the leaves from the stems.

Discard the stems.

Peel the eggs and put the yolks in a mixing bowl. Coarsely chop the whites and reserve. To the egg yolks add the lemon juice, 2/3 of the herbs, 1/4 teaspoon salt and the yogurt . Liquidise using a hand blender.

Stir the sour cream into the mixture. Add the coarsely chopped egg white. Finally add the remaining finely chopped herbs.

Season with more salt and lemon juice to taste.

If possible allow the sauce to rest in the fridge for an hour or so for the flavours to combine. Allow to come back to room temperature before using.

Gently bend the asparagus spears until they snap. Trim the broken ends. If necessary finely peel the lower sections of the stalks of the outer fibrous layer.

Put water to a depth of 2cm into a lidded sauté pan that is wide enough to take the asparagus in a more or less single layer. Bring to the boil. Put in the asparagus and simmer until tender. For thicker or older spears this may take as long as 5-6 minutes. Fine spears and those just picked will take far less, 2-3 minutes at most. Take the asparagus from the water and spread out on a paper towel on a plate to drain and cool quickly.

Arrange the warm asparagus on plates. Spoon over some of the sauce. Decorate with reserved herb leaves. Eat with fingers.

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN