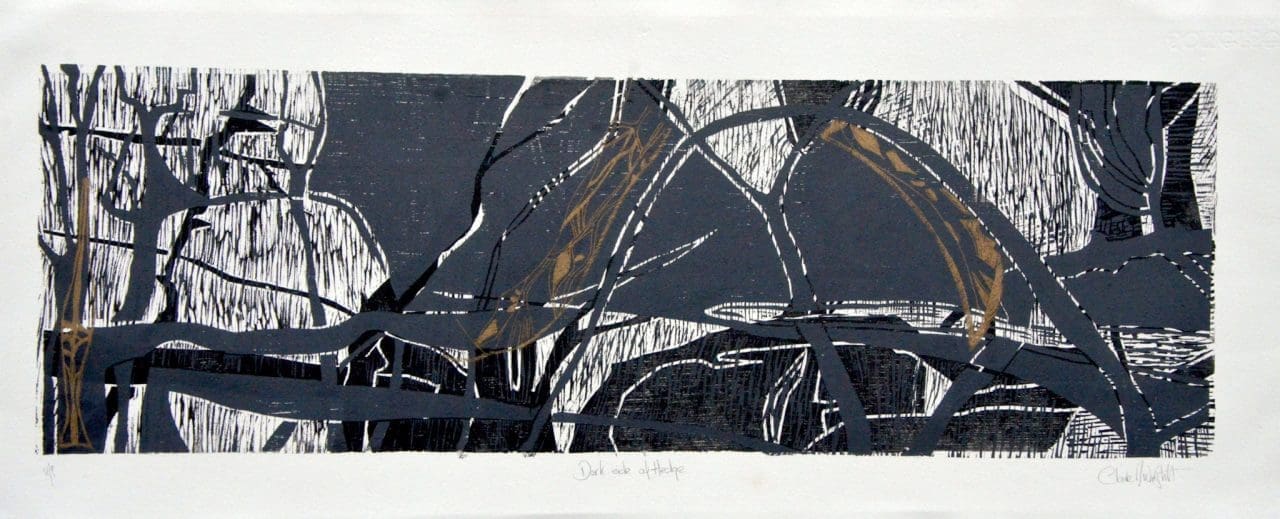

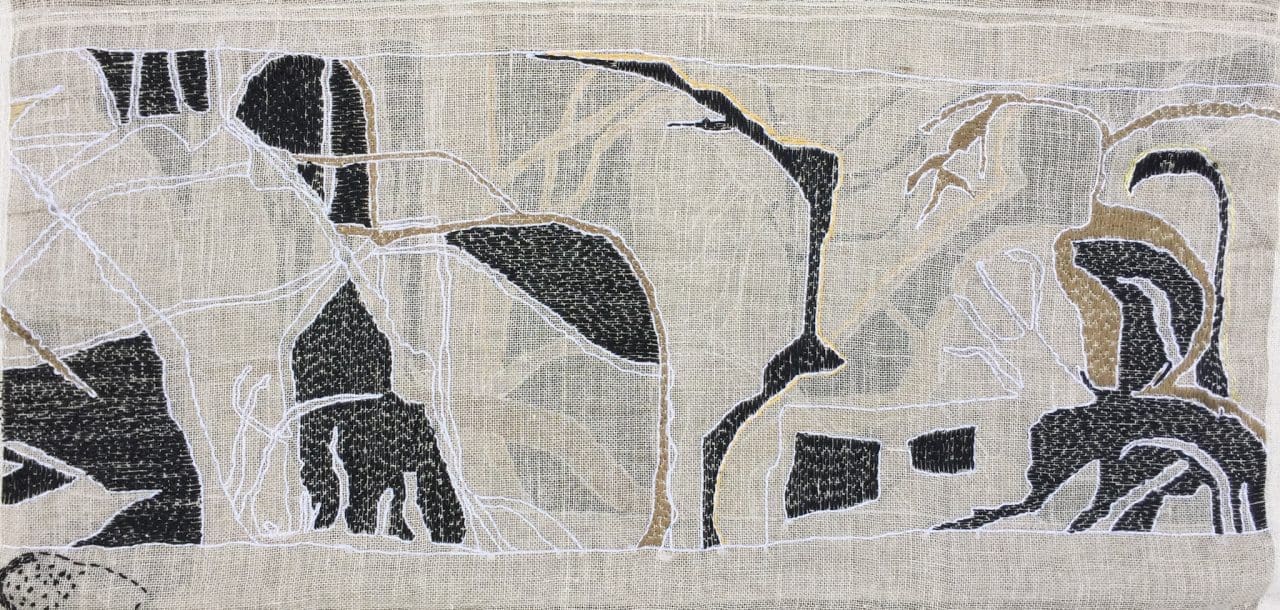

Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

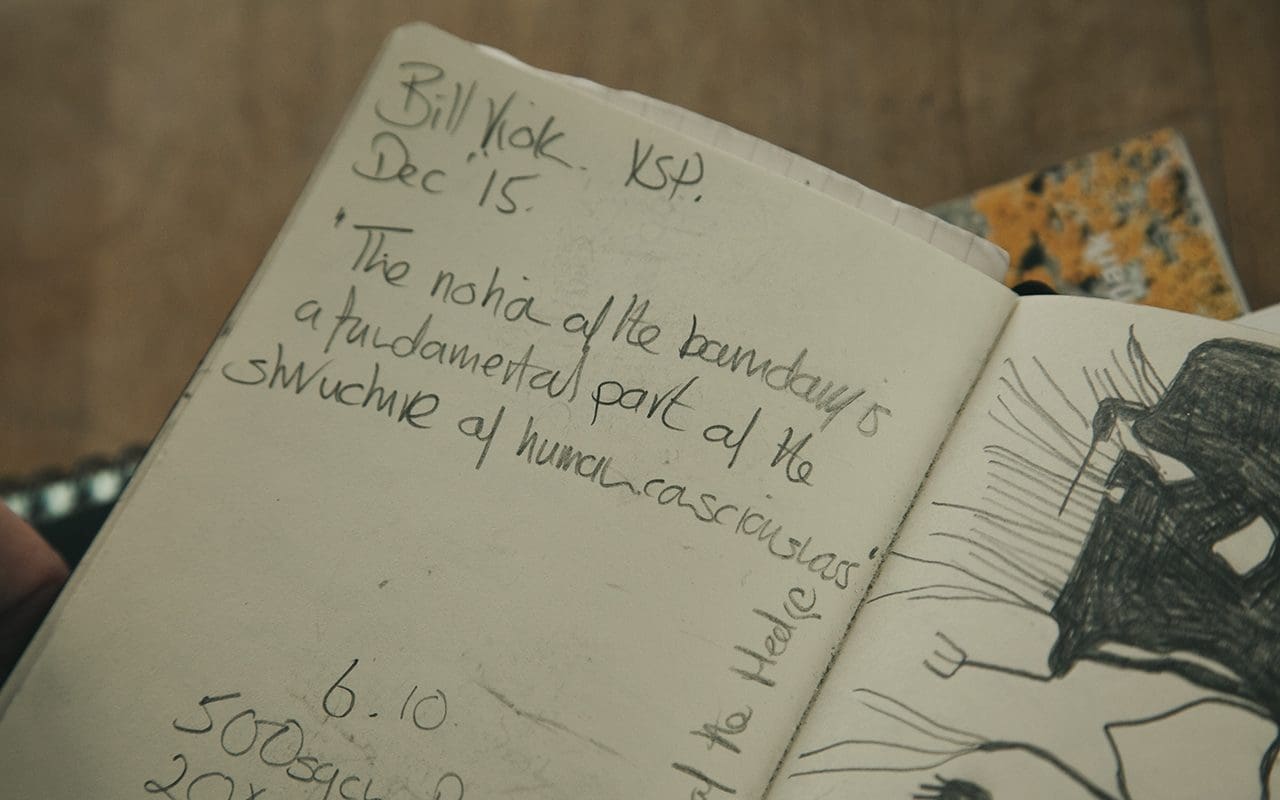

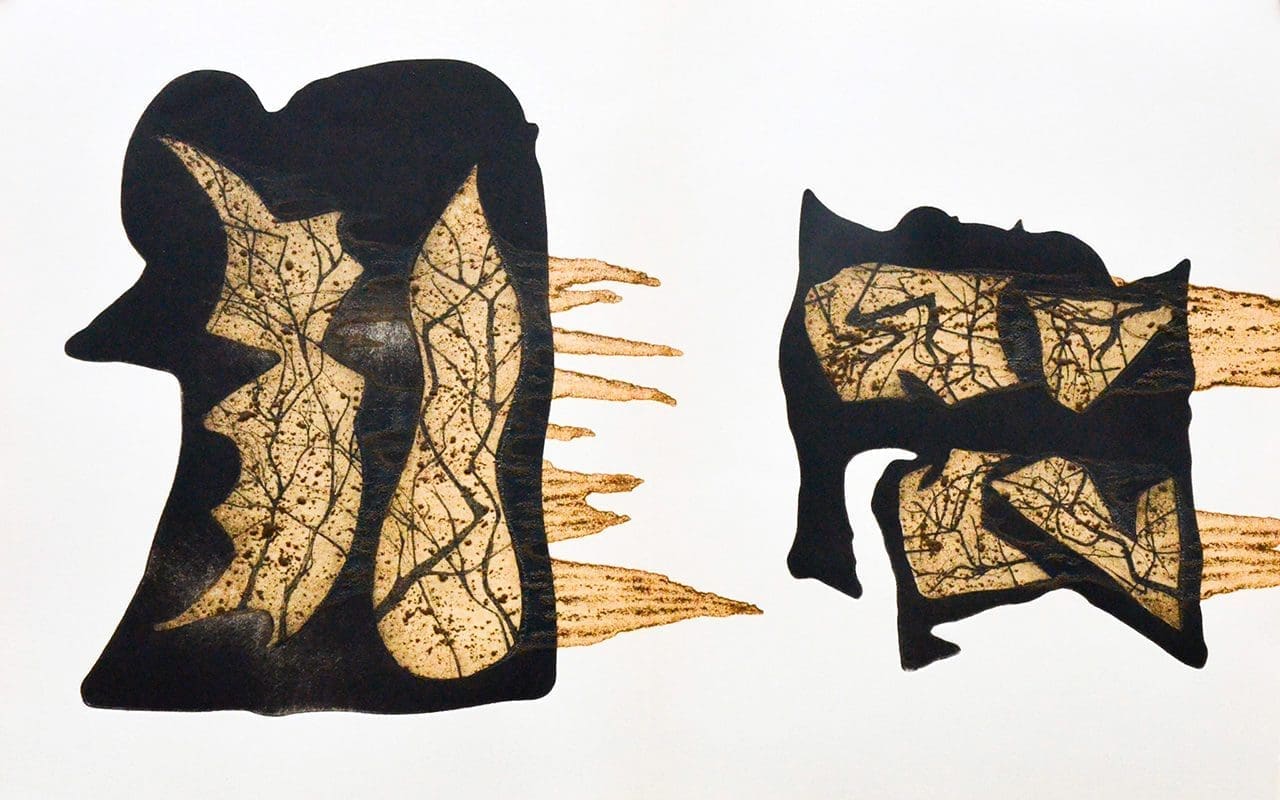

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

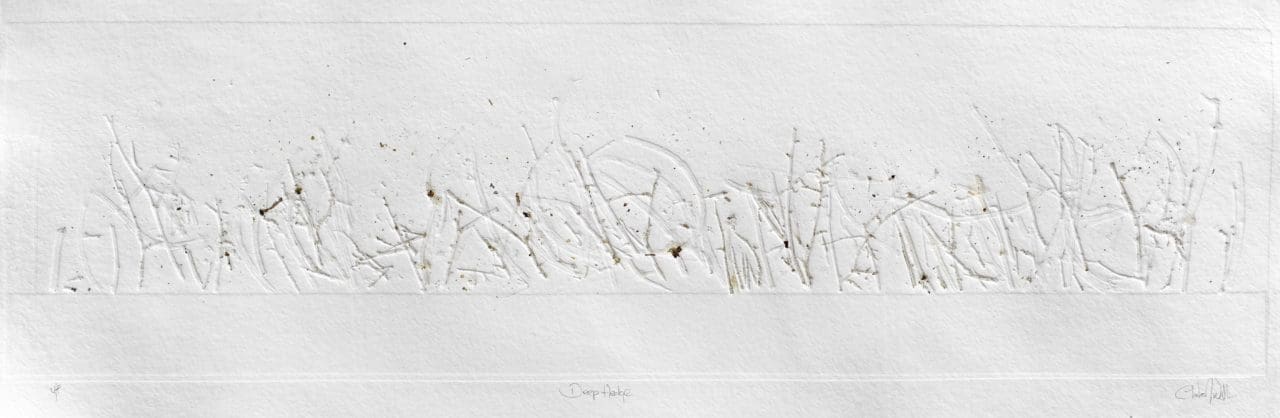

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

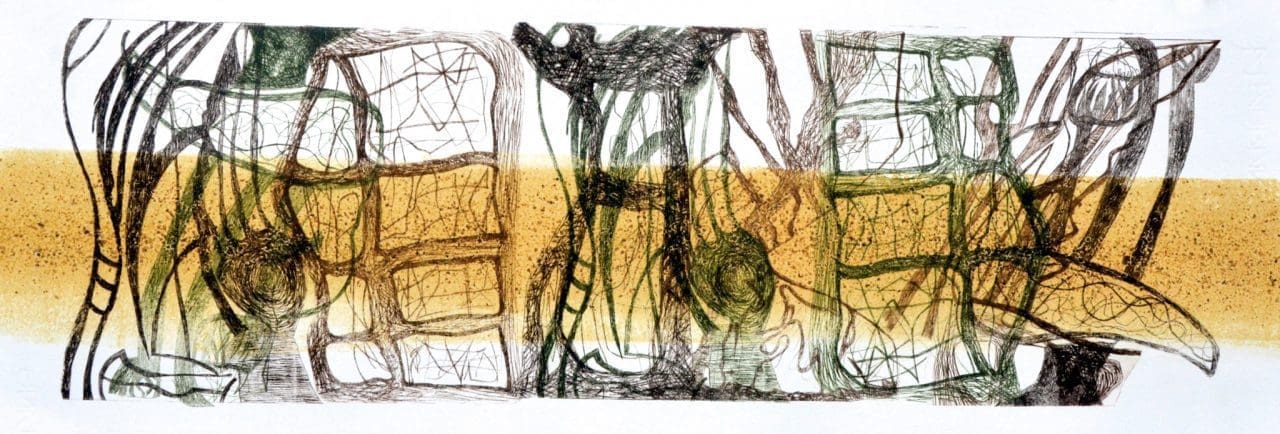

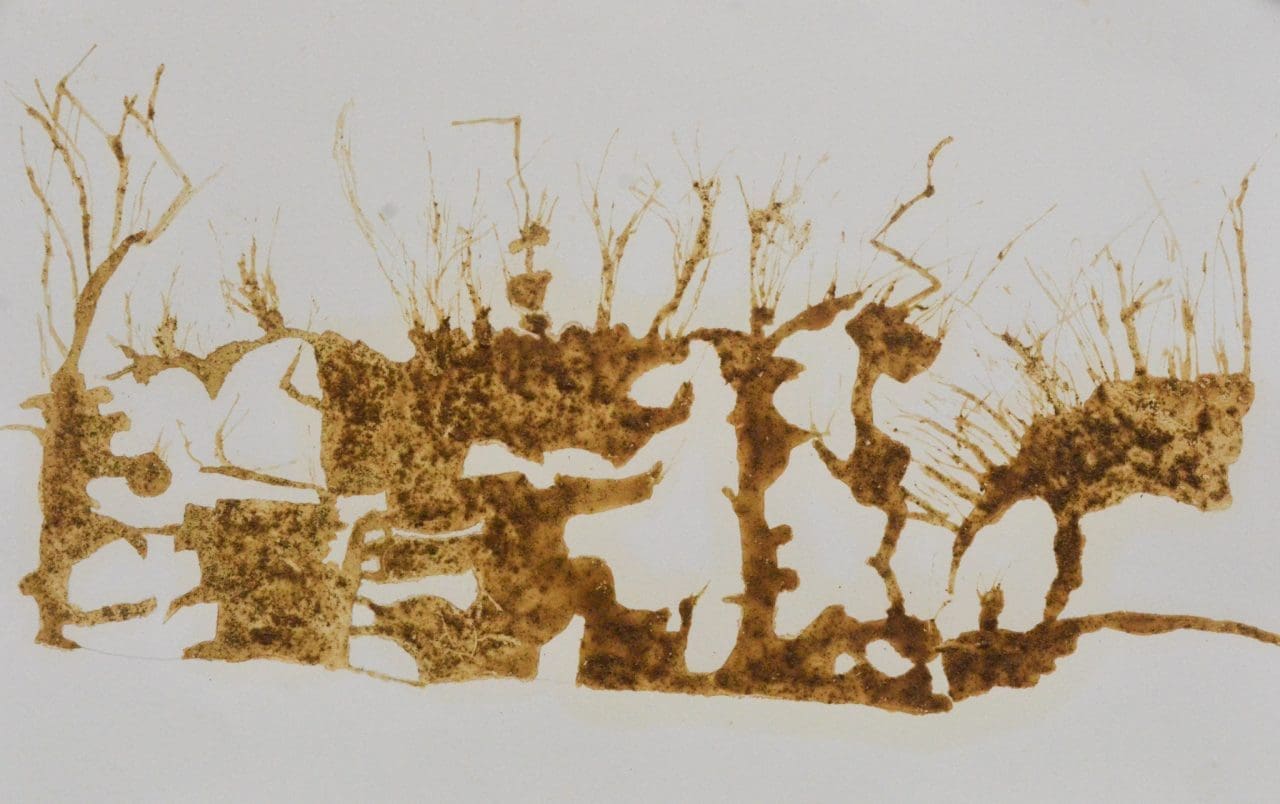

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

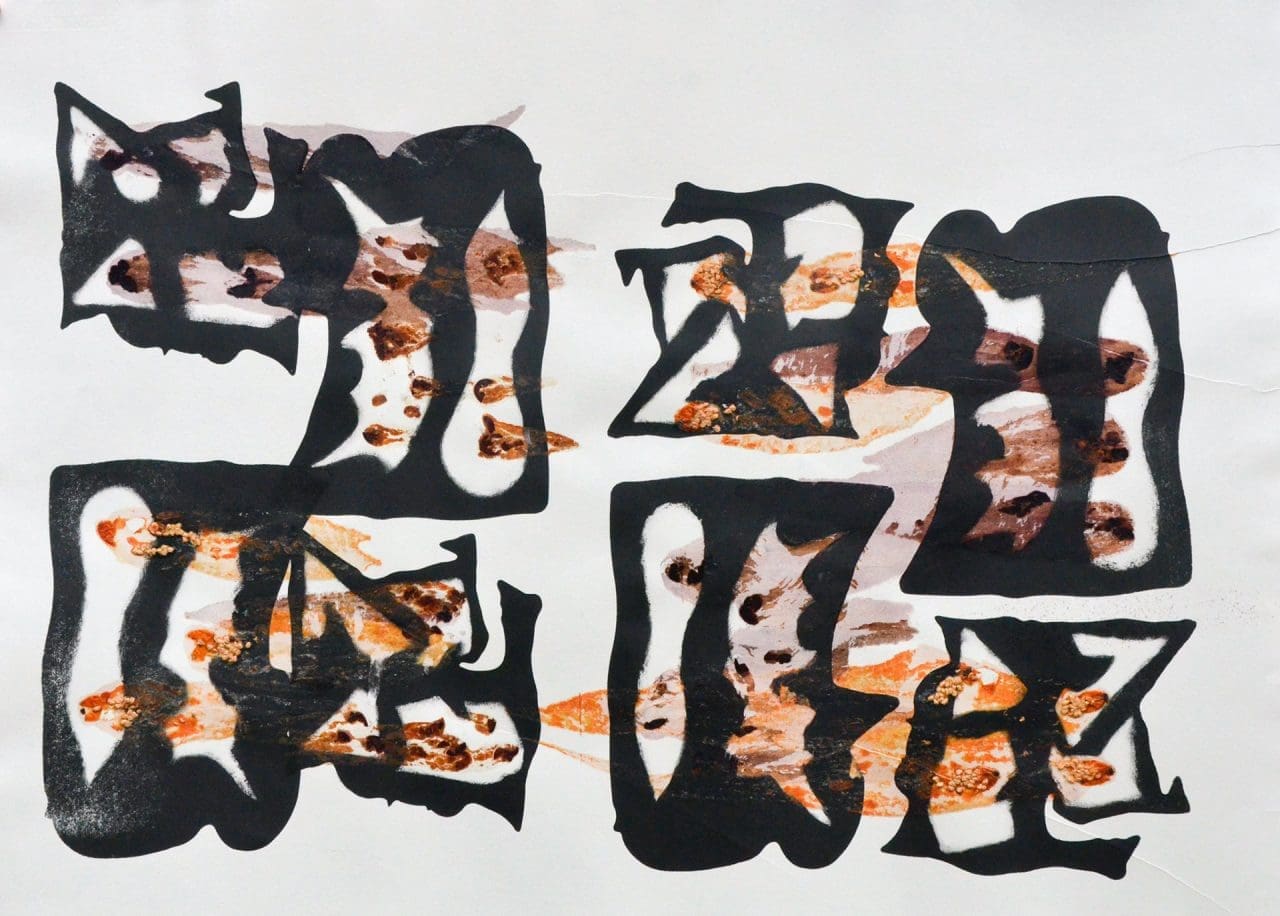

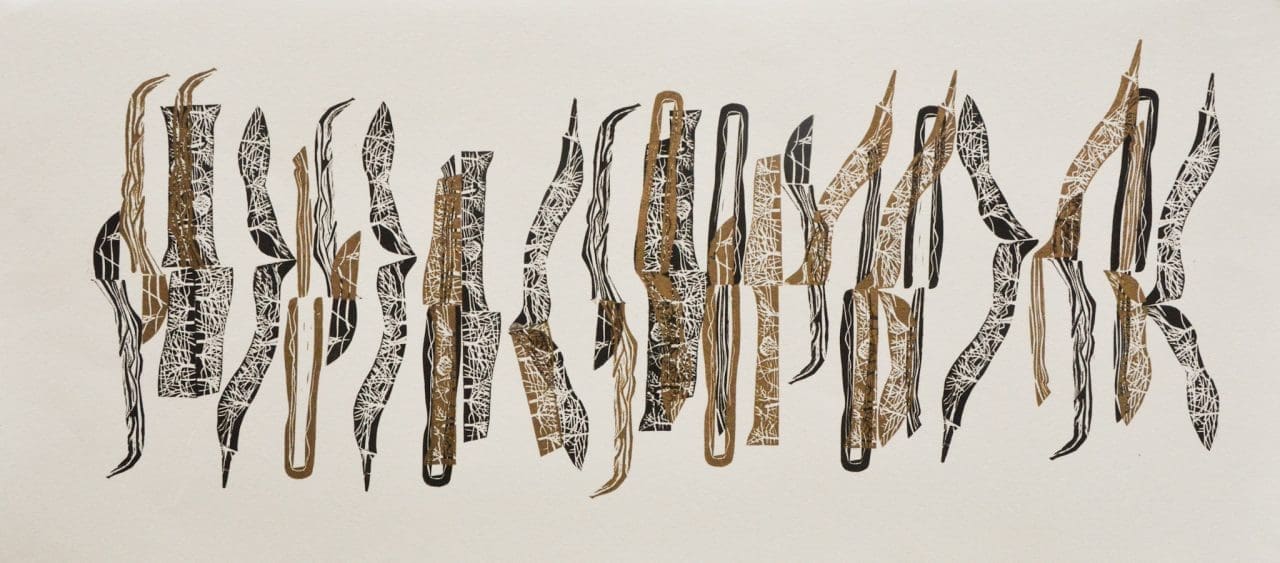

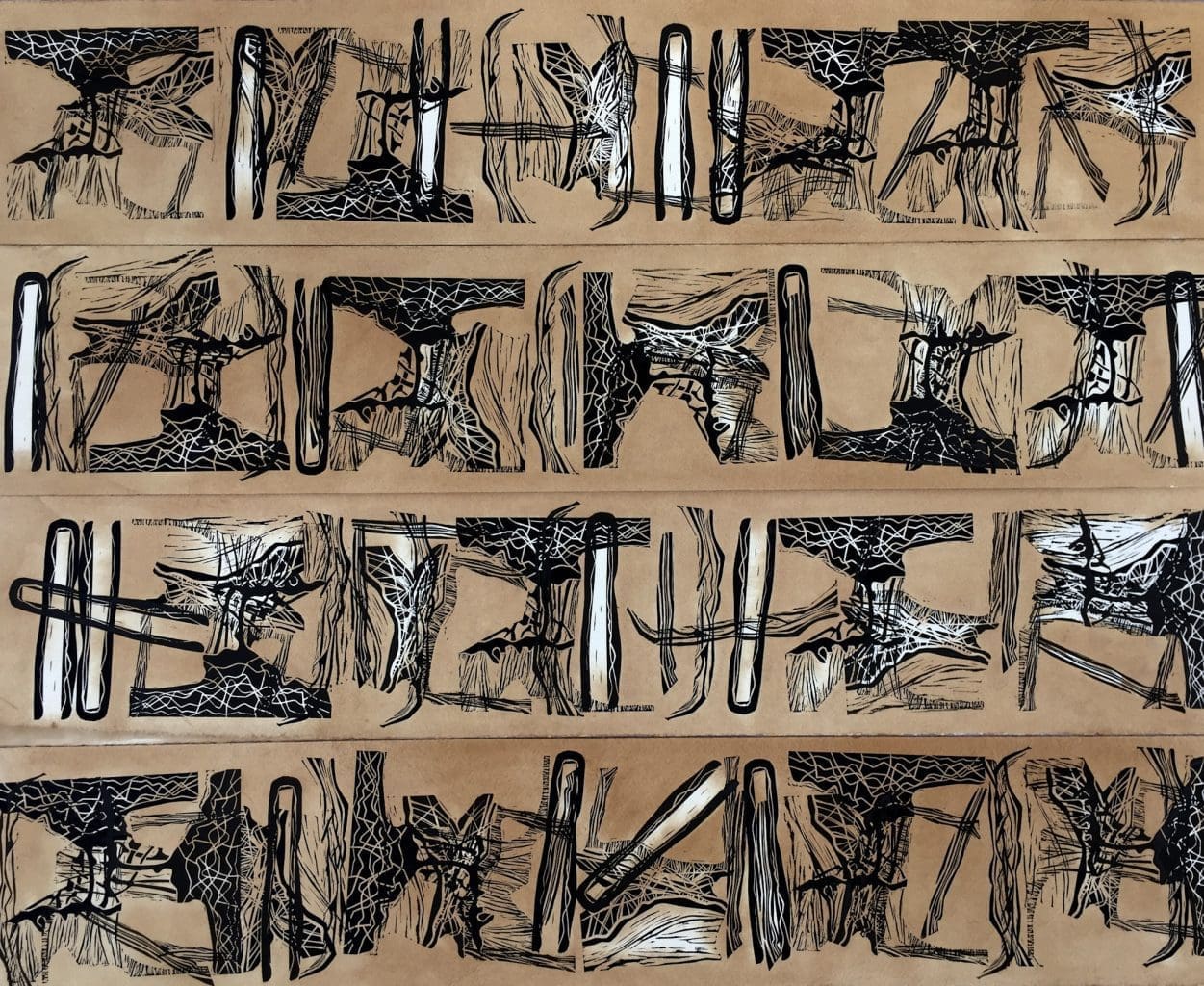

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

Adam Silverman is a potter living and working in Los Angeles. After initially studying and practising as an architect, in the early 1990’s he was one of the founders of cult skate wear company X-Large. Since 2002 he has been practising as a professional potter. As a keen amateur potter myself, two years ago I was inspired to write him a fan letter and was delighted to receive an email from him inviting me to visit him at his studio, which I did in October 2016. Adam generously gave me two days of his time, showing me his studio, his work and explaining his process. This March he has his first European solo exhibition in Brussels at Pierre Marie Giraud.

Adam, how did you come to work in ceramics ?

Ceramics is something that I started as a hobby when I was a teenager, around 15 or 16. Before that I did wood turning and glass blowing. Clay stuck and I continued taking classes as a hobby throughout high school and college. In college I studied architecture, but took ceramic classes whenever I had a free period. I never studied it per se just enjoyed doing it. I didn’t know anything about making glazes or firing kilns or the history, ancient nor modern. I continued making pots as my creative outlet after college and while I began my working life in Los Angeles, first as an architect and then as a partner in a clothing company.

In about 1995 I bought a small kiln and a wheel and set up my own studio in my garage at home and the hobby grew into more of a passion and then into a fantasy life change. In 2002 I attended the summer ceramics program at Alfred University in upstate New York with the intention of studying ceramics seriously for the first time. I wanted to learn about glazing, firing, history, etc. and to see what it felt like to work on ceramics full time, 8-10 hours a day, in a serious studio context, with feedback from people who weren’t friends or family. My idea was that at the end of the summer I would decide to either commit to working professionally as a studio potter, or give up the fantasy and acknowledge clay as my hobby but not my profession. It was a great summer and I returned to Los Angeles and set up a proper studio, outside of home, got a business license and went to work as a studio potter. I gave myself one year to see if I could make a living at it. That was fall 2002, so it’s been 15 years and in many ways I feel like I’m still just getting started.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

Adam’s Glendale studio in 2016. He has recently moved to a new studio in Atwater.

I’m interested in how you see the relationships between the seemingly unrelated disciplines of architecture, clothing design and production and ceramics.

Ceramics, clothing and architecture are all “functional arts” or at least can be. They are all made for and in many ways dependent upon the human body. They are all usually seen as “design” more than “art”. I moved from the hardest and most complicated (architecture) in terms of the amount of people and money needed to realize your work. Making clothing is very similar to making a building in terms of the process, but much faster and cheaper and less dangerous and less regulated. Ceramics I can and do make entirely alone. I have as much control over the process and results as I want. It is an amazing thing to come to work alone and be able to make what I want, when I want. This, in a way, is one of the reasons that I call myself an artist rather than a designer. I come to my studio and make what I want. I don’t have clients to service or problems to design solutions for. It’s not a service business that I am in. Anyway, you get my point I’m sure.

From 2008 to 2013 you worked as a studio director and production potter at Heath Ceramics, a tableware producer founded in the 1940’s with a distinctive Californian modernist aesthetic. What can you tell us about your time there ?

My time at Heath was great. I learned so many things, some about making ceramics and issues of production, some about design, some about running a growing business with a rapidly increasing number of employees and the associated complexities, and some about myself and what I wanted to be doing with my work and my life. It allowed me to work commercially and so not have to worry about money so much, while still giving me the freedom to both develop their homeware ranges with my aesthetic input while also producing more experimental work of my own.

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced during Adam’s time at Heath Ceramics. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

When I first encountered your work the forms you were making were controlled and symmetrical and served as canvases for extreme textural glazes. Since then your work has become monumental, less controlled, more chaotic. How has your approach changed since you first started to pursue ceramics professionally ?

I think that I have been following a path without preconceptions of what I wanted my work to look like or be like. The evolution of the approach and the results have been very organic. The one consistent is the potter’s wheel. I love working on the wheel, that’s the foundation of my studio and, in a way, my life. The work has evolved from very clean and tight, reminiscent of modern Scandinavian ceramics, and into a much looser and freer interpretation of those same basic geometries, which are dictated, or at least implied, by the forces of the spinning wheel, circles, spheres, eggs.

I can say that there really isn’t a thought process per se behind the evolution. It is more of a physical evolution. There is a lot of improvisation on the wheel. I think as I’ve aged and become more confident as an artist, things have very naturally loosened up. In the early days I would on occasion think that I was too tight and needed to loosen up. I would intentionally try to make looser work and it always felt horrible, contrived and unnatural, and the results didn’t feel like my work. I felt that they were terrible to look at and touch.

You have developed your own glazes over many years. Can you explain how you do this ?

I am a total caveman when it comes to chemistry. I put stuff together and burn it and see what happens. I’ll find materials where I am working and use them to leave marks on the work. Usually I start by thinking about just a colour or group of colours that I want to use and then start making things and see where it goes. I use glaze recipe books, the internet, and sometimes commercially available glazes as a starting point, and then start altering them through experimenting. Also I multi-fire everything, often many times, to build up layers or to try to correct something. It’s all a bit of a mess honestly, and I can’t really repeat anything, which I like.

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

An installation at Laguna Art Museum, 2013-14

Can you tell us about your Kimbell Art Museum project in 2012, which brought you back into the orbit of some of your architectural heroes ?

This was a commission to create a body of work celebrating the 40th anniversary of the opening of the Kimbell in 1972. It is one of architect, Louis Kahn’s, finest buildings. In 2010 construction began on a new Renzo Piano designed building, while behind the original Kahn building is The Fort Worth Modern Art Museum, designed by Tadao Ando. Both architects were much influenced by Kahn.

For me as an architecture student, and then a young architect, each of these three architects were very significant, and they continue to have a bearing on my practice as a potter. So to be given this opportunity to engage with the three of them was exhilarating and terrifying. I made three large pots using only materials harvested from the site, which included items gleaned from the partial demolition of the original Kahn building, rust shed from a Richard Serra sculpture and water from the pond at the Ando building.

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots produced for the Kimbell Art Museum and an installation view, 2012. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

What attracted you to the Grafted project that you collaborated on with Japanese botanist Kohei Oda ?

This project was suggested and orchestrated by our mutual friend Tamotsu Yagi, who is a brilliant designer and art director. He also designed the book of the project as well as my Rizzoli book of a few years before the Grafted project.

Kohei creates ‘mutant’ cactus plants by grafting different species together. Tamotsu thought that I would be a good person to create pots for some of these plants and set us up on what was essentially an international blind date. I was reluctant to do pots for plants as I felt that I had moved past that part of my life and practice, but his work is so special and powerful that I couldn’t say no to Tamotsu. We did a few test pieces where I sent him a few pots and he sent me a few plants and the results were encouraging and exciting so we decided to do the two part show, one in Venice, California and one in Kyoto. We made a total of 100 pieces together over the course of a year. It was a pretty special project.

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Kyoto, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

Installation view of Grafted, Venice CA, 2014

It is self-evident to say that the forms and surfaces of your pieces are organic in quality. What are your inspirations and intentions with these forms ? Your recent show at Cherry & Martin in L.A. was titled Ghosts. Can you explain why ?

In a way I prefer for the work to stand on its own without explanations of influences, intentions. I will tell you that I look a lot at painting, anything from Cy Twombly to Monet to Rothko to Philip Guston. I look a lot at architecture. And dance. But in the end none of that really matters, because I’m making pots and sculptures that must exist on their own in the world.

The title Ghosts (and, at my upcoming show at Pierre Marie Giraud, Fantômes) simply suggests the histories and lives that are inherent in the pieces. Living organisms in the clays and glazes, my hands and actions on the clay, gestures frozen. Lives stopped, but that also live on.

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Installation views of Ghosts at Cherry & Martin, Los Angeles, 2017. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Landscapes, both urban and rural, are present in your work, and there appears to be a strong Japanese influence. What can you tell us about these ?

Yes there is a lot of this stuff in the work, and all mostly unconscious or not specifically intentional, beyond using materials harvested from my surroundings, both urban and rural. I like the idea of scars and marks coming from the place where I’m working. It’s abstract and people don’t need to know and usually don’t, but to me it feels like the place is in the work and the work is of the place and somehow it resonates and means something, even if it is unspoken and invisible.

Japan is deep in my heart and DNA. When I was in architecture school I was (and still am) a huge fan of Tadao Ando and my first trip to Japan in 1989 was specifically to look at Ando buildings. I’ve been going back there my entire adult life and have so many influences from there inside me that it’s hard to tell where it starts and ends.

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Pots for Fantômes, Pierre Marie Giraud, Brussels, 2018. Photos courtesy Adam Silverman

Fantômes is at Pierre Marie Giraud from March 8 – April 7 2018

Interview and all other photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 February 2018

Marcin Rusak is a London-based Polish designer who explores themes of consumption, ephemerality, aging, decay and longevity in his work. For very personal reasons he has chosen to work with flowers in a range of different ways. I recently met him at his new studio where he talked to me about his history, his process and his creations.

Tell me how you arrived at this way of working with flowers.

It was quite an adventure for me to get into the Royal College of Art. It started with me studying European Studies, not liking it, doing interior design on the side and trying to get into art school in Poland. They didn’t accept me. So I tried the Design Academy Eindhoven, the conceptual design school, not knowing at all what conceptual design is. I was supposed to be there for four years, but after two I felt I wanted to experience more, and the way Dutch education works is they wipe your head clean and they inject their tools into you and after four years you’re only allowed to use those tools. So after years of study I knew that I wanted something more. I wanted freedom, so that’s where the RCA came into the picture.

At the RCA you’ve got this amazing ability to make mistakes all the time, and find your own thing. So I found my own thing through an accident again, because there was a brief to find an object that interests you, like from your past or wherever, just something that you like.

And so I found this cabinet that we had in my family house, which was from the 17th century. It’s a Dutch cabinet, and it’s carved in wood, and the whole sculptural decoration is inspired by nature and the seasons. So I just started investigating, ‘Why is it that I like it so much ?’. So the first natural step for me was to go and investigate nature and flowers – the subjects of the carvings – and I went to a flower market for the first time. And that’s where I started seeing all this waste. And because I was always interested in processes, I took the waste material and started doing everything I possibly could with it, to get somewhere, not really knowing where it was going. And that’s how I discovered printing with flowers.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flower printed textile, 2015. Marcin is standing in front of this in the main image (top). Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

On your website there is a video of you making one of these textiles. What is the liquid you were spraying on the flowers ?

Vinegar. It helps to bring out the natural pigments in the flowers, and it also helps them to penetrate the silk. I also use special silks made specifically for digital printing, because they are treated with substances which react with ink, and although the flower pigments are not inks the silk reacts in the same way and the pigments become more light fast. When I first tried with normal silk the colour only lasted about a month. These pieces are about a year old and have not really faded that much, but they will fade eventually, although they will never completely disappear. I still have all the ones I made, as it is really hard to sell things that don’t last, but people have started to understand me better now, and they are prepared to buy the idea along with the object. Also recording the process of making the work becomes part of the work itself.

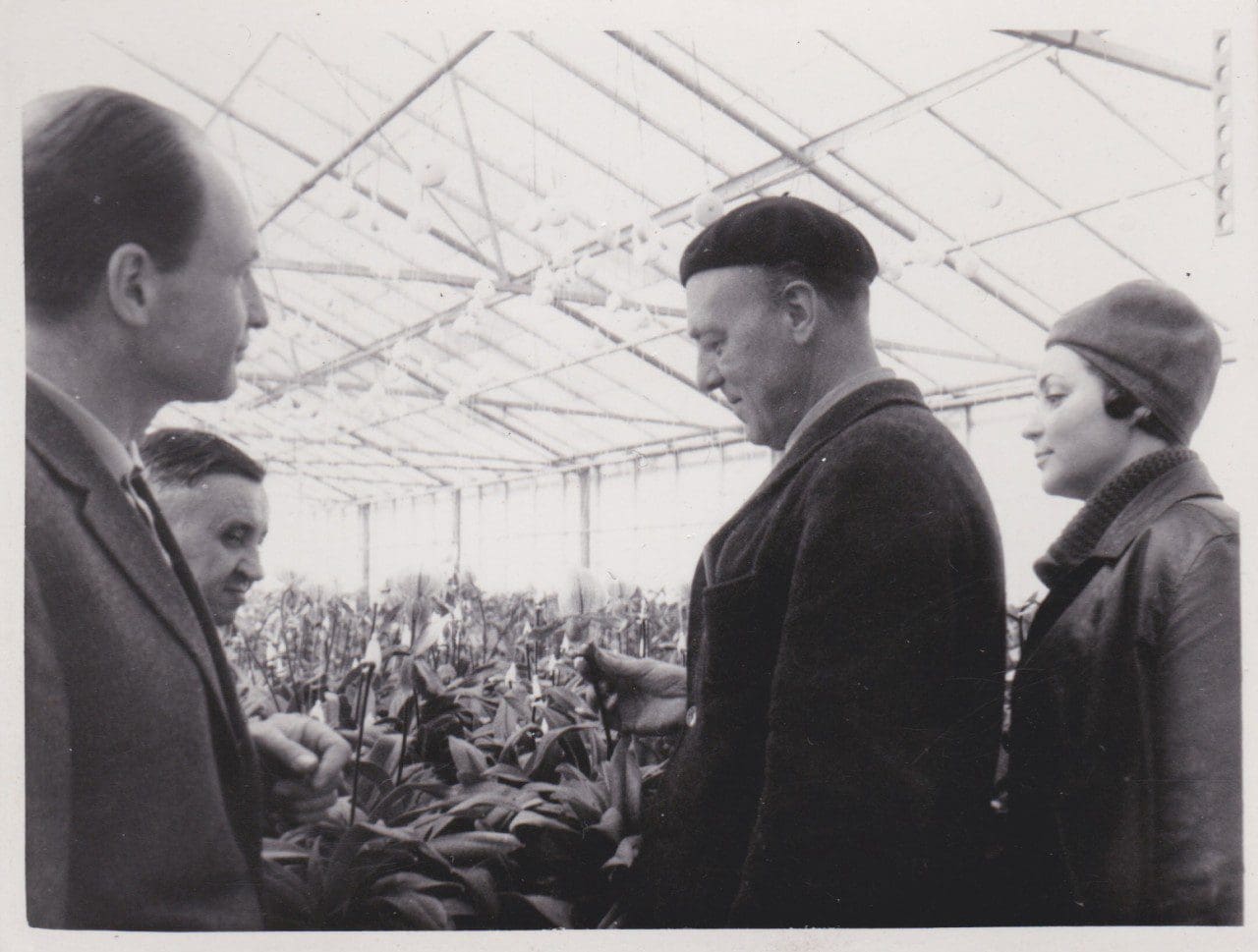

By the end of this project I went to my tutor, and I said, ‘You know what? It’s actually really funny that I’m doing these things with flowers now, because I have a history of 100 years of flower growing in my family.’

When I was born the business was closing down, so maybe about two or three years after I was born it closed. So until I was 26 and at the RCA I really had nothing to do with flowers.

I was raised in those abandoned glasshouses. That was my childhood playground. It was amazing. I still have this memory of the very dry warmth when you were in the glasshouses, but there was nothing else, just these pipes coming out from everywhere, and all these steel structures, but no flowers, no natural material. And then we moved when I was 10. My mum always loved flowers and she always wanted to do something with them, but she never did.

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Marcin’s grandfather inspecting orchids in one of the family greenhouses. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So the flowers weren’t really in the family, they were in this amazing history we had, because my grandfather, and his father, for over a hundred years they were growing flowers. They also had flower stores, so they had a really big business, mostly growing orchids. And my grandfather was kind of a freako scientist, so he was really bad with people, but amazing with plants. So actually discovering this was a breakthrough for me, but it was also quite natural. Although I kill plants, or I use dead plants or I make objects that die !

But it made me think. I remember having this conversation at the RCA with one of the tutors, they asked, ‘Why are you doing this, actually ? It’s nice that its this textile that extends the life of already dead flowers by months or years, so that’s great, but what’s the interest ? Think about it. Why ?’

So then I started doing much more research work in the Netherlands and actually trying to understand why people manipulate flowers so much these days, and how flowers became a commodity, and how they are being sold in Tesco and grown in Kenya, and flown with planes and using water in places that don’t have water. All of the background of what people don’t know about commercial flower growing. And then I started explaining to people that it’s a bit like the food industry, that started to change 10 years ago, when we started realising how we source food and intensively farm it and so on and so on. So I established a connection with Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, right next to the massive flower market there. And I made a book about it.

So you got into the science of flowers through doing this book, which you hadn’t really thought about before ?

No completely not! Because, you know, like a lot of people I just didn’t know what the situation was with flowers being grown, because we don’t have to eat them, so we don’t really think of them in the same way that we think of food, because in a way, they are perceived as a luxury. So I started investigating it at the university and they helped me a lot. At the beginning they were very suspicious of what I was doing, because they work with a lot of big brands which pay a lot of money to get their research and I was going in there saying ‘Hey, can you tell me about this ?’ for nothing. But I established a nice connection and they let me see a few things and we started talking and I introduced to them to the idea of the flower monster that I wanted to do, which is basically combining everything we want from flowers today. From retailers, to growers and consumers, everyone wants flowers to be a certain way, either living longer or smelling better or being cheaper to ship. And in the end they should be this natural imperfection, and not manipulated so much, so for me it was interesting to think about how to put that all into one piece and start communicating it to people and make them aware.

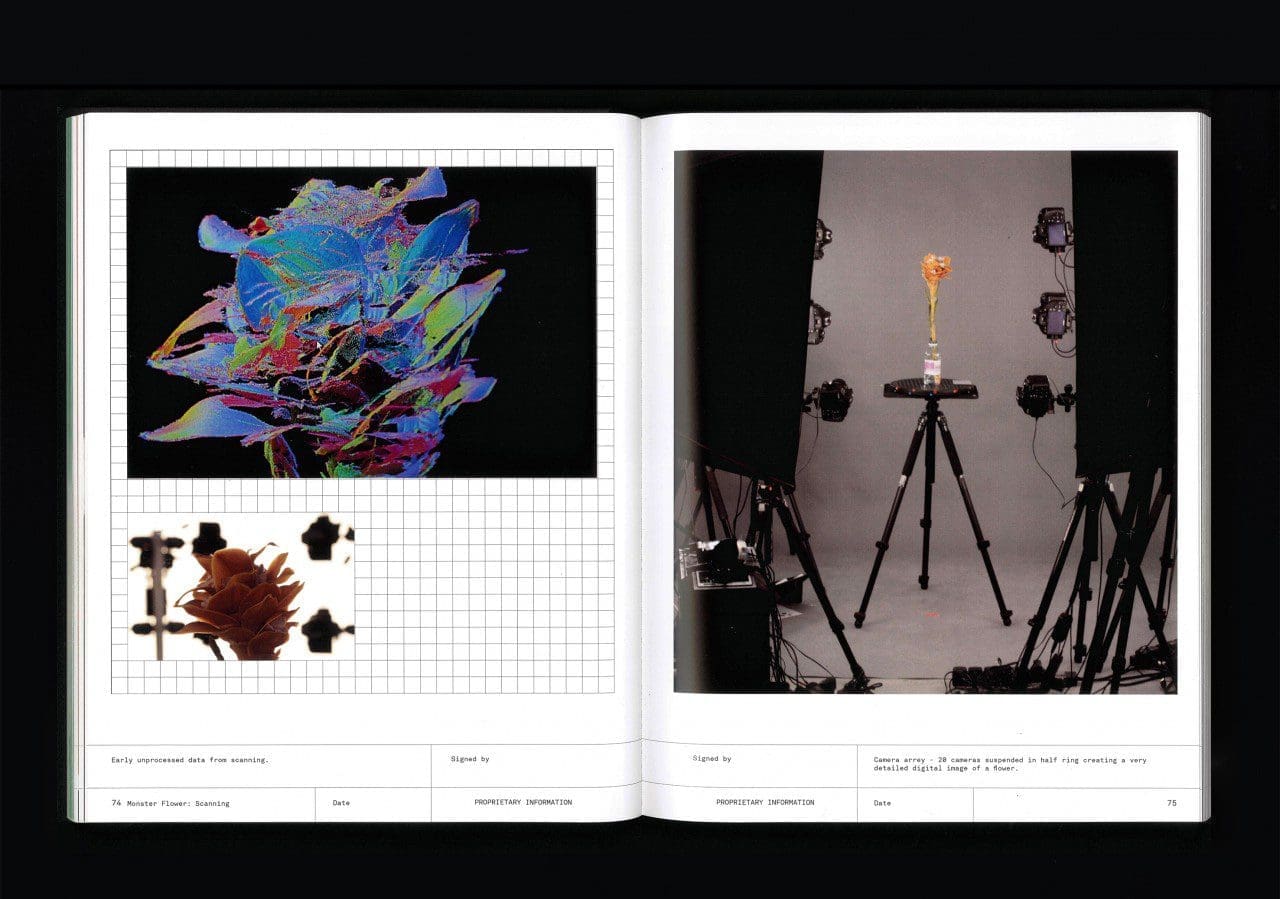

So the idea was to create this flower that does it all. So if we play with the DNA, and if the industry keeps on going the way it is right now where we keep manipulating things, it is where we might end up. I first started talking to plant geneticists to try to understand about breeding and cross-breeding, because it is possible to cross-breed a lily with a bamboo and so on. So if you have a lily which has a stem with genes from a bamboo it can then stand on a strong stem and hold this whole creature up. But how do we get there physically ? How do we make it happen ? So we researched the plants that have the certain characteristics that we needed, so anthuriums are very light, so transportation would be easier, and bamboo for the stem, or orchids with their roots outside the plant which could transport nutrition, so the whole thing could live for months. So I started working with Dutch flower engineer Andreas Verheijen, who agreed to help me with the project, and we basically took the plant species, cut them up and put them together them as nature might. Then it was flown to London in a day. It was the weirdest thing I ever did.

We created a number of hybrids. Each one came from a purpose. The way that they look is accidental. We were never thinking about them aesthetically. So when I came to the UK I had about a day to scan the first one. We used a camera array – 20 cameras standing in a circle. They shoot constantly while the object is spinning and they build up a 3 dimensional digital image. However, this digital file has no functionality. It can’t be printed. So I hired a 3D sculptor, Ignazio Genco, who then spent two weeks re-sculpting the digital files on a computer, so that they could be printed. The original one was made out of 22 separate 3D printed pieces, with a steel structure inside. It took 72 hours of straight printing.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Monster Flower II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Pages from the book showing a digital scan and the camera array. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

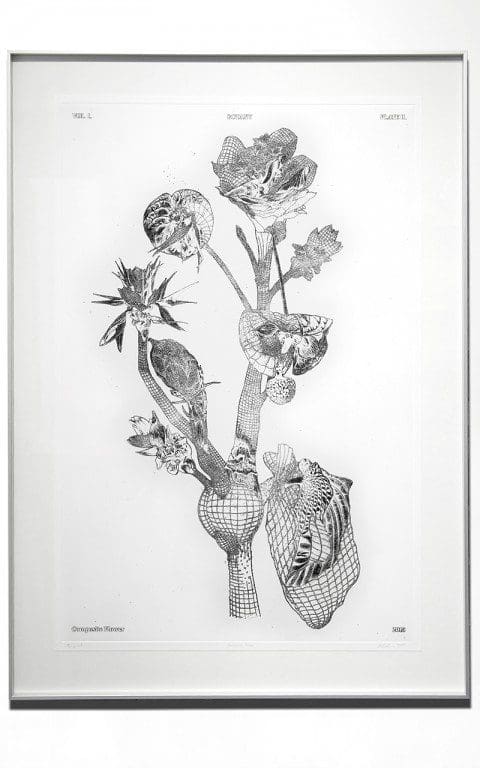

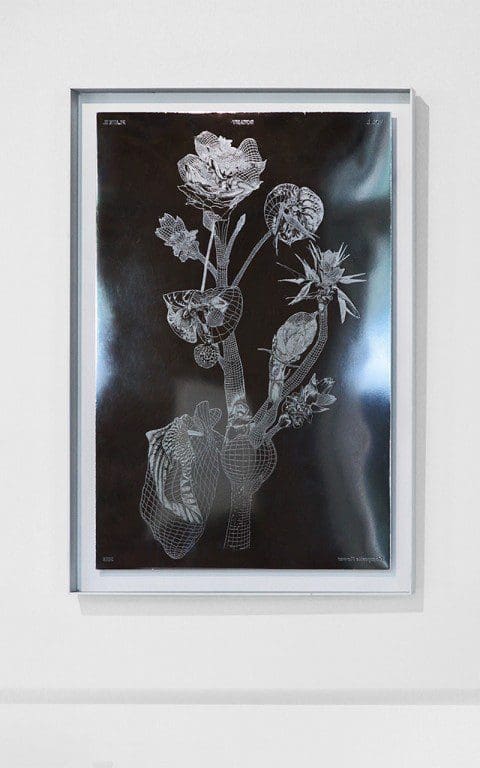

So that was the research, but I wanted to go further in telling the story. So I made these printing plates, like in the 16th century, when they discovered a new species of plant they would create a drawing of it and make multiple prints of it. So I started working with an illustrator, Clara Lacy, and we did it exactly as they would have done it, so we had the blow up details with information, we acid-etched it on copper, then we made the prints – monoprints in a run of about 15 – and then we chromed the plates to make them into permanent artefacts. I also produced a book of the whole process, as I wanted to extend the story as much as possible.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Botanical Drawing, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Chromed Botanical Printing Plate, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

So that is how my practice works. Half of it is research, where I spend my time and money investigating what I’m really interested in, and then the other half is taking bits of it and translating it into ‘object’ work, which is where the recent resin work comes from. That all started with the research I was doing into aging materials. I was really interested in the ephemeral, the idea of value, the idea of things not being permanent.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Perishable Vase II, decaying.

Tell me how this vase encapsulates those ideas and values.

We have so many things around us that we don’t really necessarily want to keep – we are stuck with their materiality – like a mobile phone case for example, which is useless after two years, but you are still stuck with the object. So I started thinking of how to make objects that aren’t permanent.

So you have a vase like this, which is made with organic binders, tree resins, shellac, beeswax, cooking flour, and dried flowers. This one (Perishable Vase III) is made with shellac, which is a natural resin excreted by beetles. I mix it with flowers, which I collect and dry and process and organise in ‘libraries’. Then I make this material and then I form it in moulds to create the vases. Because it is made from organic and natural materials the idea is that, if you don’t take care of it – for example if you put it outside – within a month it would just disappear. So there is this contrast where you create something which visually you might appreciate, but you have this back thought that it will disintegrate if you don’t take care of it. So I wanted to get people to think about objects by making something that is not permanent.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III, 2015.

Perishable Vase III (detail).

Perishable Vase III (detail).

There’s also the idea that it is something you don’t have to have forever.

Yes. I wanted to make an inkjet printer with this technique – looking at the idea of planned obsolescence, where a printer is designed to print 5000 pages and then it breaks down and you have to buy a new one. So if you could use this material to make a printer body you could just dump it in your garden when it is finished with and it would rot. But this material is so far away technically from what you need from the body of a printer that I decided to create a more symbolic piece, which is a vase.

And then the investigation into nature is an extension of that, thinking of the process of aging, not necessarily actually disintegrating, because of course I do actually need to sell things, but I was really interested in creating a material that evolved, so that you don’t replace it, but you want to experience the change. In the way that brass or leather age and we appreciate it for what it is.

So I started working with this PhD research graduate from Kew, and we started injecting bacteria into flowers and casting them in resin. When resin cures it reaches very high temperatures, so the bacteria needed to be able to live without oxygen and at really high temperatures. So over time the bacteria destroy the flowers within the resin, but leave the form of the flower trapped in the resin. The idea was to create a material in which light would eventually replace the flowers within, like ghosts. I had this vision of this strong black resin and then light comes in and you only see the voids after the flowers have disappeared.

Then, instead of bacteria, I started using air, because air does a very similar thing. If you allow air into the resin then the flowers shrivel and die and gradually you see this halo of light around the structures. In the Flora Table you get this silvery effect. So the flowers don’t rot and go brown, they don’t disappear, they just start becoming silvery, with these voids of light around them. So a bit like a Flemish painting, but with the aging factor.

I was also interested in going back to this idea of natural decoration, how often we are inspired by nature to create decoration, but how rarely we use nature itself to create decoration.

I started casting the flowers in big blocks of resin and slicing them up and opening them almost like a cheese, and then misplacing the slices. Each of the slices in this screen comes from four different resin blocks of flowers. Sometimes I keep track of how I cut them when I reassemble them, other times they are arranged completely randomly.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

The Flora Screen can be seen behind Marcin in his new studio, a Flora Table is in the foreground.

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Flora Screen, 2015 (detail).

Do you fabricate all of these pieces yourself ?

I did! It was really hard work. I made these pieces for an exhibition last September, and I was late with everything. When you are coming up with a new material there is so much to learn through the process. You think you know and you keep learning. I am still learning so much from this material. I didn’t know so much about resin at the beginning, so I made these moulds and added too much catalyst, and the resin started bowing because it was shrinking too much, it was curing too quickly. So I had to do a good few runs of resin casting to get the result I wanted. Then there was so much work with cutting them and sanding and so on.

Now the process is much better. I have specialists that I go to with certain things, but I still do all the flower collection. Until recently I was also doing all the casts on my own, but because each object becomes bigger and bigger – right now I am working on a commission for a 2 metre long table – so the scale of the project requires other people, more pairs of hands. So I work with resin specialists, metal specialists. I am still very engaged with the work. With the resin casting I do all of the arrangement of the flowers. I do a few arrangements at the same time and then choose the one that I like the best. It’s a bit like painting. You choose them for their structure, but also for their colours, volumes, and then make these compositions. Once I am happy with a composition it goes in to be cast. Still during the casting there are so many things that can go differently.

I use a mix of both dried and fresh flowers. I have the size of the mould, so I know what my ‘canvas’ is, and I have all my plant libraries, which I take with me. I have times of the year when I collect a lot, and dry them and then have to keep them dry. When I need fresh flowers I get them when I need them. And then I arrange them and then there is the casting procedure.

It took me a year to get to the point where the flowers weren’t burnt or shrunk by the resin, nor for the flowers to affect the resin curing, because if you put moisture into the resin it prevents it from curing properly. It’s a very slow process and took a lot of development to get there, but I’m not going to give away my recipes!

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

Some of Marcin’s dried flower libraries including lilies, roses, astrantia, delphinium, limonium and cornflower.

What is intriguing about your work is that it is clearly very complicated to produce and yet the pieces are very simple.

There is so much technicality that goes into it, and it requires a lot of specialists. It has also been a problem with my work that producing it was really expensive at the beginning when I was producing in a self-initiated way, rather than with commission-based work. And when you are a recent graduate you find it really hard to do, which is one of the reasons, to start with, I did everything myself.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Table (detail).

Flora Table (detail).

Are you primarily being commissioned to produce the furniture items at the moment ?

Yes. Actually creating the furniture work – the easiest to understand for people – has helped with the appreciation of my other work. People started getting the idea of the decaying vases much better and so I started getting commissions for these too, and now I am doing these resin pieces made in the same way as the screen, that are more like paintings. They will be framed and can also be used as wall panels. So half my work is commissioned work, and the other half is just me putting time and effort into investigating new things.

What are you working on right now ?

Right now I am working on a flower incubator. It comprises this desktop ‘machinery’ – all of the parts form a complicated system of water exchange, temperature control, hydroponic nutrition – designed to prolong the life of a cut flower to see how much longer we can possibly extend its life. So this is the opposite of the idea of constant disposable consumption. It is taking something that is already starting to decay and attempting to give it longevity.

The incubator is technically a very challenging project, and so I am having a lot of help with different specialists, so it is taking much longer than previous projects. Generally I have realised that I must take as much time as I need to develop what I want to do, rather than pushing things too quickly. It’s quite easy in this world to get trapped into working with other people’s deadlines, especially interior designers, as aesthetically the resin pieces are being seen as statement pieces for interiors. So currently I have quite a lot of enquiries from interior designers wanting to use these furniture pieces in their work.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

Flora Lamp, 2015. Photograph courtesy Marcin Rusak.

How do you manage that in terms of how people perceive your work ?

I am only just starting to realise that there are these differences between, say, the interiors world and the art world. When I started, for me it was all the same, I didn’t really know. Because I’m so interested in the idea and what these pieces are conceptually the selling outcome was something far from my mind. Now I am starting to distinguish how much work and commitment actually goes into creating a working piece of furniture. The resin material gives them an added value, but what I am most interested in is creating the value in the material itself – by the fact that it ages, or is not permanent.

So I am trying to shift my practice right now into this world where the pieces are appreciated for the conceptual idea. I spend quite a lot of time going out and talking to people, giving talks, to explain the work, because if you put a vase like this on a plinth and you just leave it as it is without a label people just say, ‘Yeah, it’s a vase.’, but if you give the story of why it was made and what it’s going to do in a couple of years they really perceive it differently. So the longer I am working the easier it is to make the work because people already understand it. At the beginning it was really hard to come up with the idea and have people understand it. The furniture pieces give people an easier point of entry, as people like them first for their visual aesthetics, and then when they get deeper they realise that there is this whole body of work. Of course, aesthetics are a very important part of my work. Not as the ultimate outcome, but more as the result of an investigation into aesthetics, either through making natural decoration or the aesthetics of things that decay and don’t last. I think aesthetics are incredibly important and we should never forget about them, but they are never the primary goal in my work.

So where do you see your work going ?

There are still two paths currently. One where it is more applied fine arts, and the other is me investigating this idea of impermanent things. I’m in a group show in September. I’m doing more of the vases for the show. And I’m thinking of making a decaying glasshouse where the front of it is so fine that it just disappears. That’s something that really stimulates me and gives me energy to work.

It’s also a lot about grabbing from the pool of inspiration from the past and mixing it with everything I am doing right now, like the story of flowers and the consumption aspect. One feeds the other, and then they start to feed themselves. So I guess I’ll see where that goes, but I’m really about thinking through making, so I have to be making to come up with things. It’s never just me thinking about making something and then doing it, they are all an outcome out of the past research, my palette of tools and materials, and you go with all of them until something starts getting somewhere and then you pick the ones that go somewhere and start working on developing them further. I’m excited to see where it’s going to go. I’m working on having a different creative head space where it’s all about making, so just letting myself make mistakes and experimenting.

Nowadays we are so keen to have ‘new, new, more, more’ all the time, I am trying not to get trapped in this way of thinking and take time to actually develop these approaches I have started as far as possible. My practice is also a lot about people being able to come and see the pieces, so I am really happy to now have a space where I can meet people and show them the work and explain the ideas. For it is one thing to see an image on the internet, but quite another to come and talk to me about where it’s coming from, and also the possibilities of what I can make for them.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology, 2015.

Flower Entomology (detail).

Flower Entomology (detail).

Can you tell me about your relationship to nature, gardens and flowers ?

I would say that it keeps coming more and more. I started off as a blank page where I was interested in other things, but the more I work with these objects the more I appreciate nature. I have started thinking about flowers very differently. I don’t have this need to have them around me so much, as I look at them as a kind of material, and I see so much waste that it terrifies me to even think about going to buy more of them, and I don’t have a place where I can grow them as I live in central London.

Strangely plants have become a lot more intriguing to me, also because of my investigations and my talks with plant geneticists, but on just a very personal basis they have become much more, I would say, friends, where they are just this amazing source of nature you can hold in your hand. My room-mate shares the same idea and we now have more plants in our flat than I think we do cups ! It makes home so much more relaxing, especially in London.

And if you think that my past was in this 2 acre central Warsaw garden – because not only did we have the glasshouses, we also had a very particular garden, because my grandfather grew not only flowers, but all the garden plants as well. Then I lived first in the Netherlands, a small city with not all that much nature around, and now I am in London, and I am missing it a lot, which is why I have this desire to go and be in nature every now and then.

My sister and I have also just started a business together around flowers, doing artistic flower installations in Warsaw, because first of all it’s something that she is really into – it is in her DNA, she was never trained – but she just makes these amazing compositions and arrangements, and there is a big niche there for that there, as all the florists are doing the same kind of thing. No one is really thinking of flowers in terms of them being local or seasonal, or in working on the composition almost as a sculpture or painting. We’re using the same name as my grandma used to call her flower shops, which is MÁK, which means poppy seed in Polish. We only started about 4 months ago and so I am travelling to Warsaw a lot more at the moment, because we are doing this together, as she’s very young, she’s 25, so I am trying to support her, but she is the main engine and inspiration, she does all of the compositions herself. And she dries flowers for me too. She uses lots of flowers in her installations and everything that comes back to her is being dried and re-used in my work.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

Resin and flower sample, 2015.

What would your grandfather think ?

I’m really curious. He was a very complicated man with a very complicated way of connecting with his family so I didn’t really know him that well, but I think he would be secretly really intrigued and interested. I sometimes wonder what it would be like if I could go home and talk to him about these things and get his knowledge. My sister is always seeking knowledge about plants and my mum tries to give us as much of her knowledge as she can, but I think my grandfather would be an amazing source. Lately I have been digging through all the family archives and going through everything, because I have been trying to find a book of his – you know when you are a grower and you discover and record things for yourself ? – so I’m trying to find these transcriptions of what he was doing.

We had four or five really big glasshouses, and it was funny as it was in central Warsaw and he sold it to a development company, who took down the glasshouses, but they promised to keep the garden, because that was his condition. But they tricked him and they took it all down and built these big buildings and only kept a tiny bit of the garden. It was really sad, but we managed to rescue all these massive trees, and they were transported to my parents house on these huge trucks. They had to wait to build the house until the trees had been planted first.

Your work straddles worlds of art, craft and design. How do you classify it ?

With the craft, I think I was kind of put there more than it was a conscious decision on my part. But it’s so close to everything. It’s hard to even name it for myself. Like, when people ask me, “So, what do you do?” I seriously have problems answering this question. And it’s not because I’m trying to be so ‘artist’ about it. It’s just, how do you explain that it could be objects that don’t last, or it could be research in the Netherlands, or it could be investigating an actual decoration and making these resin pieces, or it could be ephemeral textiles ?

It is hard these days to say what it is. I don’t feel the need, or able, to classify it. It is what it is. It is other people who need it to be classified. That is fine with people who are open, and who are prepared to listen to me explain the ideas behind it, but closed people find it harder to grasp the idea of buying something that is ephemeral. It’s hard for some people to see value in something unless everyone else does. Some people at the design fairs have said that my work shouldn’t be categorised as design, but really that is just a tag for it. How people see it is how they see it.

Interview: Huw Morgan / All other photographs: Emli Bendixen

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage