Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

Bare-root whips of hawthorn and wild privet

I buy my bare-root plants from a local wholesale nursery just fifteen miles from here and welcome the fact that they haven’t had to travel far to their new home. This year the two-year-old whips are the bones of a new hedge that will hold the track which runs behind the house and along the contour of the slope to the barns. It replaces a worn out hedge of bramble and elder that was removed when we built the new wall and will provide shelter to the herb garden below when we get the cold north-easterlies. It will also connect with the ribbons of hedges that make their way out into the landscape. Keeping it native will allow it to sit easily in the bank and to play host to birds up close to the buildings.

This year my annual ambition to get bare-root material in the ground before Christmas has been achieved for the very first time. It is best to get bare-root plants in the ground this side of winter if at all possible. They may not look like they are doing much in the coming weeks but, if I were to lift a plant from my newly planted hedge at the end of January, it would already be showing roots that are active and venturing into new ground. With this advantage, when the leaves pop in the spring the plants will be more independent and less reliant on watering than if planted at the back end of winter.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

The new hedge will hold the track behind the house and act as a windbreak for the herb garden below the wall

Slit planting whips could not be easier. A slot made with a spade creates an opening that is big enough to feed the roots into so that the soil line matches that of the nursery. I have been using a sprinkling of mycorrhizal fungus on the roots of each new plant to help them establish – the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots and mycorrhiza in the soil, enabling them to take in water and nutrients more easily. A well-placed heel closes the slot and applies just enough pressure to firm rather than compact the soil. The plants are staggered in a double row for density with a foot to eighteen inches or so between plants.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

Adding mychorrizal fungi to newly planted hedging whips

I have planted a new hedge or gapped up a broken one every winter since we moved here and I have been amazed at how quickly they develop. They are part of our landscape, snaking up and over the hills to provide protection in the open places and it is a good feeling to keep the lines unbroken. This one has been planned for about three years, so I have been able to propagate some of my own plants to provide interest within the foundation of hawthorn and privet. Hawthorn is a vital component for it is fast and easily tended. It provides the framework I need in just three years and the impression of a young hedge in the making not long after it first comes into leaf. I have planted two hawthorn whips to each one of Ligustrum vulgare, which is included for its semi-evergreen presence. I like our wild privet very much for its delicate foliage, late creamy flowers, shiny black berries and the fact that it provides welcome winter protection for birds.

Woven amongst this backbone of bare-roots plants, and to provide a piebald variation, are my own cuttings and seed-raised plants. A handful of holly cuttings – taken from a female tree that holds onto its fruit until February – and box for more evergreen. The box were rooted from a mature tree in my friend Anna’s garden in the next valley. I do not know it’s provenance, but it is probably local for there is wild box in the woods there. I like a weave of box in a native hedge as it adds density low down and an emerald presence at this time of year.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

A home-grown box cutting

Raised from seed sown three years ago, taken from my first eglantine whips, are a handful of Rosa eglanteria. They make good company in a hedge, weaving up and through it. A smattering of June flower and the resulting hips come autumn earn it a place, but it is the foliage that is the real reason for growing it. Smelling of fresh apples and caught on dew or still, damp weather, they will scent the walk as we make our way to the barns.

The final addition are part of a trial I am running to find the best of the wild honeysuckle cultivars. I have ‘Graham Thomas’ and the dubiously named ‘Scentsation’, but Lonicera periclymenum ‘Sweet Sue’ is the one I’ve chosen for this hedge, as it is supposed to be a more compact grower and freer-flowering. There are three plants, which should wind their way through the framework of the hedge as it develops and add to the perfumed walk. Wild strawberries will be planted as groundcover in the spring to smother weeds and to hang over the wall where they will make easy picking.

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

Planting a new field boundary hedge on new year’s day 2011

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

The same hedge six years later

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan The leaves are nearly all down in the wood, winter light fallen to the floor for the first time in half a year. A new horizon meets us as we look out from the house. Not onto the weight of the poplars and their understory, but through to the slopes beyond. The tracery of branches clearly identifying one tree’s character from the next, the tilt of trunks, the hug of shining ivy.

Everywhere the scale change is remarkable and we find ourselves drawn out into the landscape with refreshed curiosity. Much of this is simply to do with a season’s growth dropping back into dormancy. Under the elderly field maple in the clearing by the stream a coppery skirt lies in a circle where the leaves fell in the still air there. Looking up into the newly naked branches a world of lichens and moss – grey, silver and green – has made them home. The nettles that just a month ago were lush and keeping us from the stream have half their volume. With continued frosts in the hollow they will be nothing but brittle stem in a month and we will be free to walk its length once again.

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

Lichen and moss on the old field maple

The stream is audible from up by the house in all but the driest weeks, but now it is charged with winter rain and the noise pulls us down to look. You can easily lose an hour or more if you start to explore the mud and shingle banks, as the stream landscape is always changing. A log from higher up, driven down by storm water, causing damming and silting up, contrasts with the constancy of a favourite boulder, marooned in a pool of its own influence, a home to moss and liverworts.

The moss-covered boulder

The moss-covered boulder

Although the stream is small and at times hidden, it is a favourite part of the property. Soon after moving here at about this time of year we started bank clearance and every year we have done a little more. A barbed wire fence that ran its length to keep the animals in the fields is all but removed now, the rusty coils disentangled and pulled free of the undergrowth and the rotten fence posts removed. As a reminder a number of oak posts that outlived the softwood ones were left to mark the old fence-line. They are now cloaked in emerald moss and, when working in the hollows, are perches for watchful robins.

In places the stream disappeared into a thicket of bramble to emerge again lower down without revealing its journey. The child in me had to know what lay within and the mounds of bramble that bridged the banks were cleared to reveal, in one case, a lovely bend and, in another, a pretty fall and outlook where I have planted a small Katsura grove. I have plans to make a shelter there for watching the water when the trees are grown up, but for now it is simply enough to have the plan in mind as a potential project.

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

The matted root plate of a mature alder holds the stream bank

Slowly, and in tandem with the clearances, I have started to plant the banks on our side where the farmer had taken the grazing right to the very edges. Although we do not want to lose the stream behind trees for its entire length, it is good to balance the volume of our neighbour’s wood on the other side and, in places, to protect the banks. The new trees, just sapling whips at the moment, have been planted so that we can weave in and out of their trunks on the walk up or down the stream and with or against the flow.

Tree planting is one of my favourite winter tasks. The young whips are ordered in the autumn and are with us from the nursery not long after the leaves are down when the lifting season starts. If I can I like to get them all in before the end of the year so that their feeding roots are up and running by the spring when top growth resumes.

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Three year old alders on the stream bank

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder whips protected from deer with cylindrical tree guards

Alder (Alnus glutinosa), a riverine species that likes to dip its feet into the water, is one of the best for stablilising the banks. The roots, which produce their own nitrogen and charge young trees with vigour, are dense and mat together to form a secure edge where the banks are crumbling from having no more than pasture to hold them together. The deer that have a run in the woods have loved the young growth so, after a year of grazing which left them depleted, I have resorted to using more than spiral guards to protect them. The cylindrical guards are not pretty to look at, but give the saplings long enough to jump up above the grazing line and gain their independence.

Alder catkins

Alder catkins

Alder leaf buds

Alder leaf buds

In the deeper shade of the overhanging wood, and where the alders have proven to be less successful, I have used our native hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), encouraged by a mature specimen that, together with an oak, teeters on the water’s edge. It too has a dense root system and loves the heavy clay soil on the banks that lead to the water. Both the Carpinus and the Alnus have good catkins, which are in evidence already on the alders. Purple-brown and already tightly clustered, with hazel they are the first to let you know that things are already on the move in early winter. The alder buds are also violet and your eye is pleased for the colour which is intense in the mutedness of December. The keys of the mature hornbeam are still hanging in there and glow russet in the slanting sun that makes its way down the wooded slopes.

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

The trunk of the oak on the opposite stream bank

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Hornbeam whips on the stream slope with the mature hornbeam beyond

Keys on the mature hornbeam

Keys on the mature hornbeam

After winter rains the stream rushes in a torrent that would sweep you away if you tried to wade across it, so this winter the stream work will turn to the bridges. Firstly to clear the remains of a stately oak that fell under the weight of its June foliage and then on to repair the clapper bridge that we made a couple of years ago and which was washed away in the heavy rains just recently. For now the fallen poplars, with their perilously mossy trunks, provide the link to the wood from which they fell. One came down the first summer we were here, and another two years later. Now the fallen oak has changed the stream once again and with it our winter diversions.

The fallen oak

The fallen oak

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 January 2017

It has been an exciting autumn, and one that I have looked forward to and been planning towards for the past six years. It has taken this long to resolve the land around the house. First to feel the way of the place and then to be sure of the way it should be.

Though the buildings had charm, (and for five years we were happy to live amongst the swirly carpets and floral wallpapers of the last owner) the damp, the white PVC windows and the gradual dilapidation that comes from years of tacking things together, all meant that it was time for change. Last summer was spent living in a caravan up by the barns while the house was being renovated. We were sustained by the kitchen garden which had already been made, as it provided a ring-fenced sanctuary, a place to garden and a taste of the good life, whilst everything else was makeshift and dismantled.

This summer, alternating between swirling dust and boot-clinging mud, we made good the undoings of the previous year. Rubble piles from construction were re-used to make a new track to access the lower fields and the upheavals required to make this place work – landforming, changes in level, retaining walls and drainage, so much drainage – were smoothed to ease the place back into its setting.

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

Of course, it has not been easy. The steeply sloping land has meant that every move, even those made downhill, has been more effort and, after rain, the site was unworkable with machinery. We are fortunate that our exposed location means that wet soil dries out quickly and by August, after twelve weeks of digger work and detail, we had things as they should be. A new stock-proof fence – with gates to The Tump to the east, the sloping fields to the south and the orchard to the west – holds the grazing back. Within it, to the east of the house and on the site of the former trial garden, we have the beginnings of a new ornamental garden (main image). An appetising number of blank canvasses that run along a spine from east to west

The plateau of the kitchen garden to the west has been extended and between the troughs and the house is a place for a new herb garden. Sun-drenched and abutting the house, it is held by a wall at the back, which will bake for figs and cherries. The wall is breezeblock to maintain the agricultural aesthetic of the existing barns and, halfway along its length, I have poured a set of monumental steps in shuttered concrete. They needed to be big to balance the weight of the twin granite troughs and, from the top landing, you can now look down into the water and see the sky.

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

On the lower side of the new herb garden, continuing the bank that holds the kitchen garden, the landform sweeps down and into the field. Seeded at an optimum moment in early September, it has greened up already. Grasses were first to germinate, and there are early signs of plantain and other young cotyledons in the meadow mix that I am yet to identify. I have not been able to resist inserting a tiny number of the white form of Crocus tommasinianus on the brow of the bank in front of the house. There will be more to come next year as I hope to get them to seed down the slope where they will blink open in the early sunshine. I have also plugged the banks with trays of homegrown natives – field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and divisions of our native meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) – to speed up the process of colonisation so that these slopes are alive with life in the summer.

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Below the house, the landform divides to meet a little ha-ha that holds the renovated milking barn and a yard which will be its dedicated garden space. This barn is our new home studio and from where I am planning the new plantings. I have placed a third stone trough in this yard – aligned with those on the plateau above – with a solitary Prunus x yedoensis beside it for shade in the summer. There are pockets of soil for planting here but, beyond the two weeks the cherry has its moment of glory, I do not want your eye to stop. This is a place to look out and up and away.

That said, I have been busily emptying my holding ground of pot grown plants that have been waiting for a home, and some have gone in close to the milking barn to ground it; a Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ from the old garden in Peckham, a Paeonia rockii, a gift from Jane for my 50th, and the beginnings of their underplantings, including Bath asparagus and some favourite hellebores that I’ve had for twenty years or more. The spaces here are tiny and they will need to work hard so as not to compete with the view out, nor disappoint when you get up close on your way to the barn. The bank sweeps up to wrap the milking barn above and to the east and the planting with it, so that it is nestled in on both sides. Below the barn there is the contrast of open views out into the fields, so when inside I can keep a clear head from the window.

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

To help me see my new canvasses in the new ornamental garden clearly I have started dismantling the stock beds. The roses, which have been on trial for cutting, will be stripped out this winter and the best started again in a small cutting garden above the kitchen garden. I’ve also been moving the perennials that prefer relocation in the autumn. Jacky and Ian, who help in the garden, spent the best part of a day relocating the rhubarbs to the new herb garden. It is the third time I have moved them now (a typical number for most of my plants), but this will be the last. In our hearty soil, they have grown deep and strong and the excavations required to lift them left small craters.

The perennial peonies, which go into dormancy in October, also prefer an autumn move, as do the hellebores so that their roots are already established for an early start in the spring. They both had a firm grip and I had to lift them as close to the crowns as I dared so that they were manageable. The hellebores have been found a new home in a rare area of shade cast by a new medlar tree that I planted when the landscaping was being done. I rarely plant specimen trees, preferring to establish them from youngsters, but the indulgence of a handful, which included the cherry and a couple of Crataegus coccinea on the upper banks near the house, have helped immeasurably in grounding us in these early days. To enable a July planting these were all airpot grown specimens from Deepdale Trees which, as long as they are watered rigourously through the summer, establish extremely well. Usually right now is my preferred (and the ideal) time to plant anything woody.

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

It is such a good feeling to have been planting things I have raised from seed and cuttings for this very moment; a batch of seedlings grown on from my Malus transitoria to provide a little grove of shade in the new garden, rooted cuttings of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ to screen the new garden from the field below, and a strawberry grape (Vitis vinifera ‘Fragola’), a third generation cutting from the original given to me thirty years ago by Priscilla and Antonio Carluccio, is finally out of its pot and on the new breezeblock wall. Close to it I have a plant of the white fig (Ficus carica ‘White Marseilles’), a cutting from the tree at Lambeth Palace, where I am currently working on the landscaping around a new library and archive designed by Wright & Wright Architects. The cutting was brought from Rome by the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole, in 1556. In 2014 a cutting made the return journey to Pope Francis, a gift of the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. The tree reaches out from the palace wall in several directions to touch down a giant’s stride away. It is probably as big as our little house on the hill, and my cutting is full of promise. It is so very good, finally, to be making this start.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan, Dan Pearson & Jacky Mills

Half the hedges on the land are allowed a year off between cuts so that, on rotation, we always have some for flower and fruit. Allowed to grow out softly from the rigour of a yearly cut the fray of last year’s wood spawns sprays of blossom as the prelude to later bounty. When the hedges are still darkly limbed the stark white of blackthorn and then wild plum is forage for early bees. Later, freshly clothed spumes of hawthorn let you know where you have the Crataegus. This is one of the most steadfast hedge components and easily tended.

Guelder rose (Viburnum opulus) follows where there is damp to sustain its particular preference, the lacy flowers like bonnets, brilliantly white amongst summer greenery. Sprays of dog rose (Rosa canina), arching free to present themselves later in June and July, start the relay between the three hedge rose species that are native. First R. canina (main image), then the Eglantine (R. eglanteria) with foliage smelling of green apples and finally the Field Rose, R. arvensis.

Come the autumn all of the above yield berries and hips, peppering the hedges with colour and providing feasting opportunities for wildlife. It is a vicarious pleasure to be able to contribute to this rich and connected network, linking one field with another, woods with fields beyond and shelter out in the open.

Crataegus monogyna – Hawthorn

Crataegus monogyna – Hawthorn

Rosa eglanteria – Eglantine Rose

Rosa canina – Dog Rose

When we arrived here the hedges were not in good condition. Neatly trimmed on a yearly basis, the ‘broken teeth’ (where fast-growing elder had seeded in, outcompeted its neighbours and then died) were now home to bramble. A little bramble in a hedge is not a bad thing but, come the winter, their open cages offer little protection and their advance, like the rot in a tooth, is to the detriment of the whole. Since moving here I have slowly been improving the hedges by gapping up to remove the weak sections and interplanting with new whips of fruiting species to make good the mix; common dogwood (Cornus sanguinea) and guelder rose where the ground lies wet, and wild privet, the wayfaring tree (Viburnum lantana), roses and spindle (Euonymus europaeus) where it is drier. I am happy with the hawthorn almost everywhere, but I’ve learned that the blackthorn should only go into a hedge that is easily cut from both sides.

Cornus sanguinea – Common Dogwood

Cornus sanguinea – Common Dogwood

Viburnum lantana – Wayfaring tree

Viburnum lantana – Wayfaring tree

Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) – or the Mother of the Woods – is a runner and it’s thorny cage quickly forms an impenetrable thicket. Over many years the centre dies out and, because the thorns are wicked (indeed, a wound from them can quickly turn septic, so best to wear leather gloves when pruning), the centre of the enclosure is somewhere that becomes free of predators. Acorns transported by rodents or ash keys blown into the protected eye will be the start of a slower and ultimately outcompeting layer that, in time, pushes the blackthorn out to the very edges of the hedge and out into the fields to claim more ground. For this reason I have planted only a handful on the land, both for their early blossom and for the inky sloes that make a good addition to hedgerow jelly or for sloe gin, a favourite winter tipple.

Prunus spinosa – Blackthorn

Prunus spinosa – Blackthorn

Now that we have been here long enough for my originally purchased whips to have yielded fruit, I have started to collect the berries before the birds have them all in order to grow my own plants from seed and so that I can continue to plug gaps with my home-grown material. The seedlings of the Viburnum opulus, the roses and the spindle have been added to the edges of the Blossom Wood as the trees have grown up and begun to shade the original shrubs I planted there as shelter.

Viburnum opulus – Guelder Rose

Viburnum opulus – Guelder Rose

The viburnum is a particular favourite, the translucent, bright scarlet drupes lighting up wherever the plants have taken hold. The Eglantine roses have also been good to have to hand as their perfumed foliage is a delight on a damp morning when the smell of apples lingers on the still air. They have been planted by gates, into hedges that we walk past frequently and upwind of wherever there is a place we use that is downwind of them. Interestingly – for deer generally target roses first of anything – the Eglantines have so far remained untouched. Is this just luck or is it the scented foliage that acts as a deterrent ? I have planted them by the entrance to the vegetable garden to see if they have the desired effect.

Euonymus europaeus – Spindle

Euonymus europaeus – Spindle

Euonymus planipes – Photo by Emli Bendixen

Euonymus planipes – Photo by Emli Bendixen

Our native spindle (Euonymus europaeus) is one of my favourite fruiting hedge plants. The pink turban-shaped fruits rupture in October to reveal the contrast of tangerine seeds suspended within. It is a dramatic combination and my original whips have shown that there are many different forms, some with fruits a brighter colour, others a paler pink but with more prolific fruit. Raising from seed is always interesting for this variation and I’ve selected the best for those that will make a link to the garden. The garden is also going to be home to shrubs that fruit, such as Euonymus planipes, which will blend the ornamental into the land beyond it where things run wilder. There is another story to be told here, but it is hard not to mention this wonderful shrub. I have two plants, both seed-raised, and they too are showing differences. The deep magenta fruits – more elegantly winged than the native – and vibrant orange seed hang in foliage that colours apricot and the colour of melted butter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

As the sun starts its descent towards autumn we are chasing it to Greece for a well-deserved holiday. By the time we return the spiders will be spinning, the apples will need picking and the garden will have begun it’s slow decline. We leave you with some late summer pictures of the garden at Hillside and the surrounding countryside to tide you over until we are back.

Photographs: Huw Morgan

This time last week we were down in Cornwall at the Port Eliot Festival. It was the second time I have been asked to speak there and to be one of the judges for the Flower Show. I have a particular fondness for the festival, which takes over the grounds of the estate, wraps around the house, runs alongside the banks of the River Tamar and nestles in a series of old walled gardens. The events and the tents and the happenings are carefully choreographed in a low-key fashion so that, as you roam the grounds, you discover as you go.

The landscape gardens were set out in the 18th century by Humphrey Repton, who made a grand move to push the river away from the house and in its place sweep a rolling lawn that connected a ha-ha in front of the house to the hills and woods beyond. I was lucky enough to stay in the house last autumn at Halloween with Perry and Cathy St. Germans, the Festival Director, and had the opportunity of looking over Repton’s Red Book. His books became one of his signatures as a designer and featured images of the existing landscape with a reveal that you could pull back to see the proposed vision. It is wonderful to walk in this vision today and for this festival to be so easily integrated into the historic setting.

Mudlarking in the Tamar estuary

Mudlarking in the Tamar estuary

Picknicking on hay bales

Picknicking on hay bales

Gyspy caravans and tents amongst the trees

Gyspy caravans and tents amongst the trees

The grounds are filled with delights. You will never see a hi-vis jacket and people are free to roam and picnic or swim wild in the estuary. The tents, which are scattered in clusters that each have their own atmosphere, hold talks, readings, conversations, cooking demonstrations and performances – anything from a discussion with an artist, musician or writer to a blindingly brilliant set by the Japanese band Bo Ningen. There are craft workshops in the Hole & Corner tent, where you can learn to forge a nail, dye with indigo, make a green oak stool or watch Britain’s last traditional clog maker at work. You can learn bushcraft skills or go foraging for food, plants and flowers to make your own botanical inks.

Indigo dyeing workshop at Hole & Corner

Indigo dyeing workshop at Hole & Corner

Traditional clog maker, Jeremy Atkinson

Traditional clog maker, Jeremy Atkinson

Bushcraft workshop

Bushcraft workshop

In the Wardrobe Department kids can take life drawing lessons from Barbara Hulanicki – with models including Oscar-winning Costume Designer, Sandy Powell – have a hat made by top milliner Stephen Jones, or take part in themed fashion shows – last year it was Game of Thrones, this year ’80’s Disco. The eateries are plentiful and always good and between events you can retire to the waterside gin bar and sit in a deck-chair people-watching with a backdrop of mudlarkers when the tide is out. There is a Wild West saloon with live music and real swing doors to make an entrance. You can take a hot tub on the banks of the river under the stars as we did, or boogie in the woods till dawn, or both if that is the way that the evening pans out.

Finding respite from the crowds in the house, the high ceilings and faded grandeur provide an elegant setting for magical installations and exhibitions of historic interest. In the Dining Room this year two articulated dolls made by Leonidas set an appropriately spooky tone, which put us in mind of The Turn of the Screw.

Life drawing with Barbara Hulanicki

Life drawing with Barbara Hulanicki

Costume Designer, Sandy Powell (right), posing for the life drawing class

Costume Designer, Sandy Powell (right), posing for the life drawing class

Dan chatting to milliner, Stephen Jones

Dan chatting to milliner, Stephen Jones

Dolls by Leonidas of La Poupée Mécanique

Dolls by Leonidas of La Poupée Mécanique

The garden, which rolls over the undulating terrain in a series of copses and clearings boasts some magnificent trees and, wherever you go, there are surprises; a huge Magnolia delavayi, a camellia walk, a maze that took Perry years to plan. The Walled Garden, which is gardened lightly today, has runs of colourful Higgledy Garden annual seed mixes jostling against high, lichened walls. A huge Crinum powelli ‘Album’ makes an appearance next to the Orangery and hydrangeas burst from behind box hedges, as if from another age. As you swing down to the estuary, dramatically spanned by Brunel’s viaduct, you are greeted by a lawn punctuated with clumps of giant Pampas grass. This is the way to see them, marching confidently across the landscape.

Higgledy Garden borders in the Walled Garden

Higgledy Garden borders in the Walled Garden

Crinum powelli ‘Album’ by The Orangery

Crinum powelli ‘Album’ by The Orangery

Brunel’s viaduct and Pampas grass

Brunel’s viaduct and Pampas grass

The serious matter of judging the Flower Show started on Friday afternoon as we took a sneak preview of the entries as they started to arrive into the below-stairs corridors beneath the house. Cool flag floors and no windows provided a perfect environment for the flowers, which were arranged on trestle tables according to the entry classes. A workbench at the end of the corridor was set up for last minute arranging and adjustments, and the judging started at 9:30 prompt the following morning.

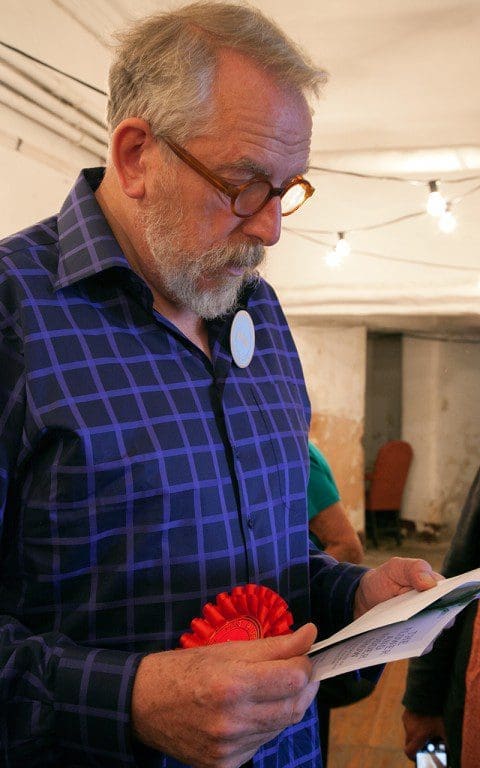

Michael Howells, the festival’s Creative Director, adjudicated. The judges, Sarah Husband, Tony Howard, Huw and myself followed behind to make our selections. A pair of redoubtable local WI members ensured that the judging was rigorous and fair, recorded the names and entry numbers of the entrants and placed rosettes and cups. The themes of the Flower Show at the festival are always inspiring and spawn great leaps of imagination amongst the entrants. True to the best of English flower shows there are sections for both adults and children.

Creative Director, Michael Howells

Creative Director, Michael Howells

Members of the local Women’s Institute record the judging

Members of the local Women’s Institute record the judging

The adult classes this year included a range of subjects marking a number of significant anniversaries. The 300th anniversary of the birth of Capability Brown was celebrated in a miniature landscape garden. I love a miniature garden and attribute my career to a rosette-winner I made when I was ten for the Liss Flower Show.

The class ‘Fire Fire !!’ marked the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London and entries used the best of high summer colour to paint this picture.

Entries in the ‘Fire Fire !!’ class

Entries in the ‘Fire Fire !!’ class

‘All the World’s a Stage’ celebrated the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, whilst ‘A Sight for Sore Eyes’ (commemorating the 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings) generated the Best in Show award with a gory battlefield, set against a bloodied English flag. King Harold, made from torn paper, arms and legs akimbo, lay with an arrow in his eye and drops of glistening blood.

Entries in the ‘All the World’s a Stage’ class

Entries in the ‘All the World’s a Stage’ class

Winner of Best in Show and First Prize in the ‘A Sight for Sore Eyes’ class

Winner of Best in Show and First Prize in the ‘A Sight for Sore Eyes’ class

‘Down the Garden Path’, celebrating the 150th anniversary of the birth of Beatrix Potter was, not surprisingly, a delight and one exhibit stood out immediately for its attention to detail with miniature tools and even a tiny cross bearing Peter Rabbit’s blue coat. It was a world within a world and a unanimous First Prize winner.

Winner of the ‘Down the Garden Path’ class

Winner of the ‘Down the Garden Path’ class

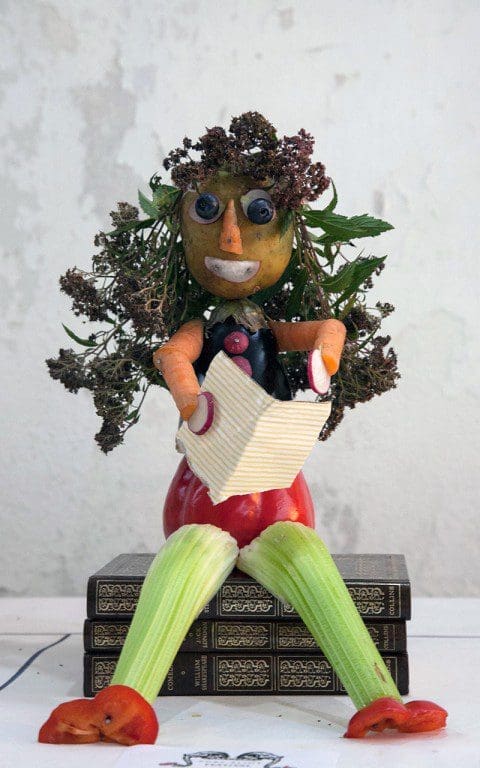

The children’s section (“‘My Hero’ – a sculpture of your favourite Roald Dahl character made of fruits and vegetables”) is always fun and shows great inventiveness, and we struggled from wondering if one or two had had adult assistance, they were that clever. I loved the anthropomorphic transformation of fruit and veg into characters. They were pure unbridled fun.

Entries in the ‘My Hero’ class

Entries in the ‘My Hero’ class

We finished by moving out into the light again to the banks by the house to judge the scarecrow competition. Ancient Magnolia grandiflora pressed themselves tight to the walls of the house and great billowing clouds furnished the sky above us. This year’s theme was Angels and Devils. My favourite scarecrow was of Boris Johnson, complete with mop of straw hair and a Brexit badge. It felt like he had found an appropriate and fitting home for himself.

Entries in the Scarecrow class

Entries in the Scarecrow class

This year’s was a particularly meaningful festival, because Perry (Peregrine Eliot, 10th Earl of St. Germans) was buried little more than a day before it opened. It was extraordinary timing on his part and, given that he and Cathy have always been the most generous of hosts, exceptionally fitting and true to his spirit that the party simply continued.

Festival Director, Cathy St. Germans

Festival Director, Cathy St. Germans

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage