Sandwiched between storms and West Country wet, a miraculous week fell upon the final round of planting. We’d been lucky, with the ground dry enough to work and yet moist enough to settle the final splits from the stock beds. It took two days to lay out the plants and then two more to plant them and the weather held. Still, warm and gentle.

I’ve been planning for this moment for some time. Years in fact, when I consider the plants that I earmarked and brought here from our Peckham garden. They came with the promise and history of a home beyond the holding ground of the stock beds, and now they are finally bedded in with new companions. There are partnerships that I have been long planning for too but, as is the way (and the joy) of setting out a garden for yourself, there are always spontaneous and unplanned for juxtapositions in the moment of placing the plants.

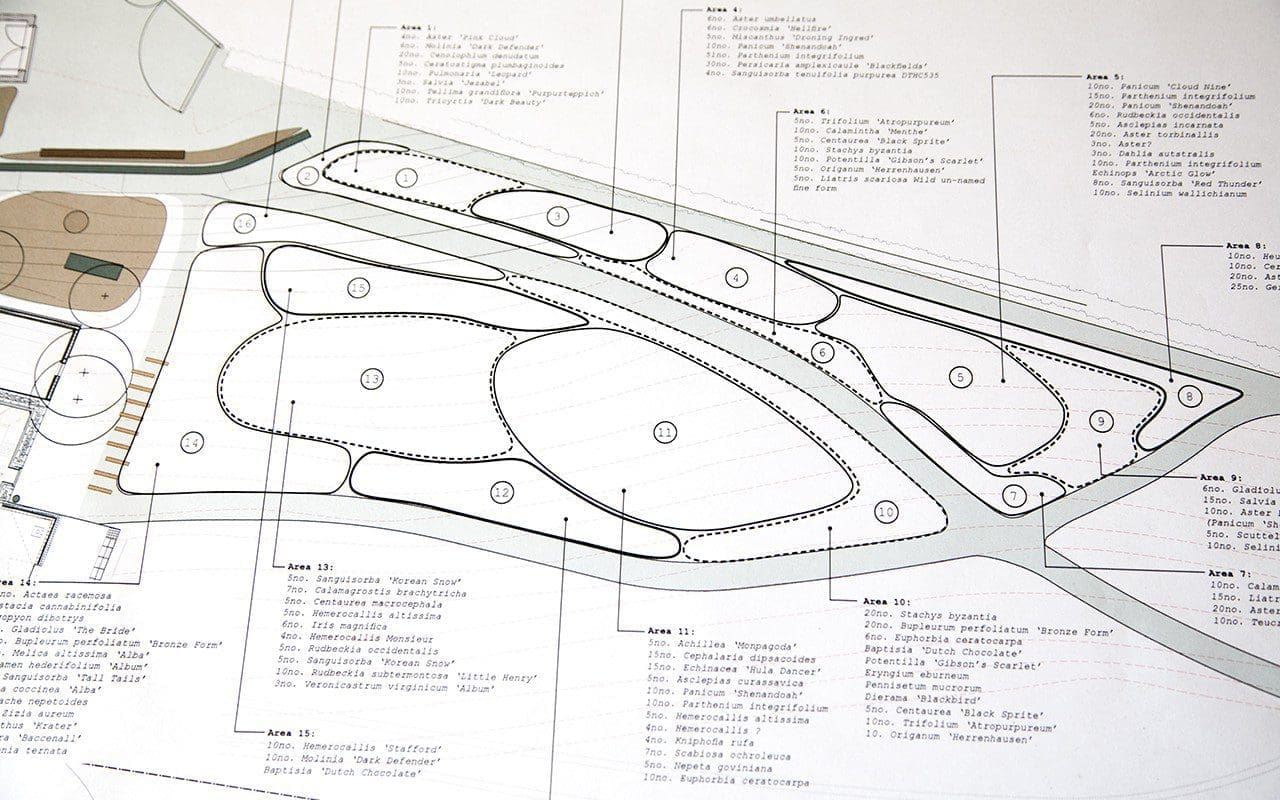

The autumn plant order was roughly half that of the spring delivery, but the layout has taken just as much thought in the planning. I did not have a formal plan in March, just lists of plants zoned into areas and an idea in my head as to the various combinations and moods. It was the same this autumn, but forward thinking was essential for the combinations to come together easily on the day. Numbers for the remaining beds were calculated with about a foot between plants. I then spent August refining my wishlist to edit it back and keep the mood of the garden cohesive. The lower wrap, with its gauzy fray into the landscape, allows me to concentrate an area of greater intensity in the centre of the garden. The top bed that completes the frame to this central area and runs along the grassy walk at the base of the hedge along the lane, was kept deliberately simple to allow the core of the garden its dynamism.

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The zoning plan for the central section of the garden

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The central path with the top and central beds to either side

The top of the central bed

The top of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The end of the central bed

The middle of the top bed

The middle of the top bed

The end of the top bed

The end of the top bed

My autumn list was driven by a desire to bring brighter, more eye-catching colour closer to the buildings, thereby allowing the softer, moodier colour beyond to recede and diminish the feeling of a boundary. The ox-blood red Paeonia delavayi that were moved from the stock beds in the spring and now form a gateway to the garden, were central to the colour choices here. They set the base note for the heat of intense, vibrant reds and deep, hot pinks including Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’ and Salvia ‘Jezebel’ on the upper reaches. The yolky Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’, lime-green euphorbias and the primrose yellow of Hemerocallis altissima drove the palette in the centre of the garden.

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Salvia ‘Jezebel’

Once you have your palette in list form, it is then possible to break it down again into groups of plants that will come together in association. Sometimes the groups have common elements like the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’, which link the new beds to the ones below them. Although I don’t want the garden to be dominated by grasses, they make a link to the backdrop of the meadows and the ditch. They are also important because they harness the wind which moves up and down the valley, catching this unseen element best. Each variety has its own particular movement; the Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, tall and isolated and waving above the rest, registers differently from the moody mass of the ‘Shenandoah’, which run beneath as an undercurrent.

To play up the scale in the top bed, so that you feel dwarfed in the autumn as you walk the grassy path, I have planned for a dramatic, staggered grouping of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’. They will help to hold the eye mid-way so the planting is revealed in chapters before and then after. This lofty grass with its blue-grey cast will also separate the red and pink section from the violets and blues that pick up in the lower parts of the walk to link with the planting beyond that was planted in the spring. These dividers, or palette cleansers, are important, for they allow you to stop one mood and start another without it jarring. One combination of plants can pick up and contrast with the next without confusion and allow you to keep the varieties in your plant list up for interest and diversity, without feeling busy.

Each combination within the planting has its own mood or use. Spring-flowering tellima and pulmonaria will drop back to ground-cover after the mulberry comes into leaf and the garden rises up around it. Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ and Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’ beneath the Paeonia delavayi for late season colour and interest. The associations that are designed to jump the path from one side to the other in order to bring the plantings together are key to cohesiveness. The sunny side of the path favours the plants in the mix that like exposure, the shady side, those that prefer the cool, and so I have had to be aware of selecting plants that can cope with these differing conditions. Consequently, I have included plants such as Eurybia divaricata that can cope with sun or shade, to bring unity across the beds. The taller groupings, which I want to feel airy in order to create a feeling of space and the opportunity of movement, always have a number of lower plants deep in their midst so that there is room and breathing space beneath. Sometimes these are plants from the edge plantings such as Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’, or a simple drift of Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’, which sweeps through the tall tabletop asters (Aster umbellatus). This undercurrent of the adaptable persicaria, happy in sun or shade, maintains a fluidity and movement in the planting.

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Stock plants of Panicum virgatum ‘Cloud Nine’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Schizostylis coccinea ‘Major’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Aster umbellatus and Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’

The combinations, sixteen in total, were then focused by zoning them on a plan. The plan allowed me to group the plants by zone in the correct numbers along the paths for ease of placement. Marking out key accent plants like the Panicum ‘Cloud Nine’, Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis, Hemerocallis altissima and the kniphofia were the first step in the laying out process. Once the emergent plants were placed, I follow through with the mid-level plants that will pull the spaces together. The grasses, for instance, and in the central bed a mass of Euphorbia ceratocarpa. This is a brilliant semi-shrubby euphorbia that will provide an acid-green hum in the centre of the garden and an open cage of growth within which I can suspend colour. The luminous pillar-box red of Potentilla ‘Gibson’s Scarlet’ and starry, white Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’. Short-lived Digitalis ferruginea were added last to create a level change with their rust-brown spires. However, I am under no illusion that they will stay where I have put them. Digitalis have a way of finding their own place, which isn’t always where you want them and, when they re-seed, I fully expect them to make their way to the edges, or even into the gravel of the paths.

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Euphorbia ceratocarpa

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’

Hemerocallis altissima

Hemerocallis altissima

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’

Over the summer, I have been producing my own plants from seed and it has been good to feel uninhibited with a couple of hundred Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Form’ at my disposal to plug any gaps that the more calculated plans didn’t account for. Though I am careful not to introduce plants that will self-seed and become a problem on our hearty soil, a few well-chosen colonisers are always welcome for they ensure that the garden evolves and develops its own balance. I’ve also raised Aquilegia longissima and the dark-flowered Aquilegia atrata in number to give the new planting a lived-in feeling in its first year. Aquilegia downy mildew is now a serious problem, but by growing from seed I hope to avoid an accidental introduction from nursery-grown stock. The columbines are drifted to either side of the path through the blood-red tree peonies and my own seed-raised Hesperis matronalis var. albiflora. For now they will provide me with an early fix. Something to kick-start the new planting and then to find their own place as the garden acquires its balance.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 28 October 2017

The self-sown sunflowers from the previous incarnation of the garden were the reminder that, just a year ago, we were growing the last of the vegetables here. I had allowed them the territory in the knowledge that this would be the end of their era, for they were in the bed that I now need back to complete the planting of the garden.

Felling them before they were finished was a relief, for suddenly, once they were gone, there was breathing space and the room to imagine the new planting. I’d also left the aster trial bed until the very last minute, eking out the weeks and then the days of its final fling. On the bright October day before we were due to lift, the bed was alive with honeybees, making the final selection of those that were to be kept for the garden that much more difficult. It was time to liberate the last of the stock beds, though, and to prepare the ground they occupied for a new planting.

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Planning what to keep and what to part with is difficult until the moment you make the first move. Over the last three years we have been keeping a close eye on the asters that will make it into the new planting. Keeping the best is the only option, for we do not have the space elsewhere and the overall composition is dependent upon every choice being right for the mood and the feeling that we are trying to create here. So gone are the Symphyotrichum ‘Little Carlow’ which, although a brilliant performer, needing no staking and being reliable and clump-forming, are altogether too dominant in volume and colour. Aster novae-angliae ‘Violetta’ is gone too. Despite my loving the richness of its colour, having got to know it in the trial bed I find it rather stiff and heavy and I want the asters here to dance and mingle and not weight the planting down.

The Aster turbinellus, for instance, has been retained for the space and the air between the flowers, as has Symphyotrichum ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ for its sprays of tiny, shell-pink flowers. I have also kept the late-flowering Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ for its modest habit and almost iridescent violet stars held on dark, wiry stems. I have always known that Aster umbellatus would feature in the planting, and so I lifted and split my three year old trial plant last autumn and divided it into six to bulk up this summer. There were many more that didn’t make the grade though, and I was torn about losing them, my self-discipline wavering at times. However, Jacky and Ian who help us in the garden eased my conscience by taking a number of the rejects home with them, and the space left behind, now that they are gone and I have finally committed, is ultimately more inspiring.

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

The reject asters

The reject asters

This is the second phase of rationalising the stock beds. In the spring, and to enable the preparation of the central bed, I split and divided the plants that I knew I would need more of come autumn, and lined these out in the top bed to bulk up; the lofty Hemerocallis altissima, brought with me from Peckham and prized for its delicate, night-scented flowers, the refined Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca, and the true form of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, originally divisions from plants in the Barn Garden at Home Farm which I planted in 1992.

I have not found a red day-lily I like more for its rustiness and elegance, and some of the ‘Stafford’ I have been supplied with more recently have notably less refined flowers and a brasher tone. I have planned for it to go amongst molinias so that the flowers are suspended amongst the grasses. Hemerocallis are easily divided and in the spring the stock plants were big enough to split into ten or so; the numbers I needed for their long-awaited integration into the planting. In readiness for setting out, and with the asters gone, we have now reduced the foliage of the daylilies by half, lifted them and then left them heeled in for ease of lifting and replanting.

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

The kniphofia and iris I had decided to keep went through the same process in March, and so the Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ and Iris magnifica were moved directly into their new positions where, just a week before, the sunflowers had towered. Similarly, the Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’ and Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’, which have both increased impressively, were lifted and moved into their new and final positions. This was in order to clear the old stock beds to make way for the autumn splits and keep the canvas as empty as possible so that I can see the space without unnecessary clutter when setting out.

The remaining trial rows – some Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield that I want in number and two white sanguisorba that will provide height and sparkle in the centre of the garden – were cut back to knee height, lifted and then split in text-book fashion with two border forks back to back to prise the clumps apart. Where the plants were not big enough I was careful not to be too greedy with my splits, dividing them into thirds or quarters at most.

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

Although October is the perfect month for planting, with warmth still in the ground to help in establishing new roots before winter, I have had to work around the trial bed of grasses and they now stand alone in the newly empty bed. Although I will be planting out pot-grown grasses next week, autumn is not a good time to lift and divide grasses as their roots tend to sit and not regenerate as they do with a spring split.

The plants I put in around the Milking Barn this time last year are already twice the size of the same plants I had to wait to put in where the ground wasn’t ready until the spring. I hope that the same will be true of this next round of planting, which will sweep the garden up to the east of the house and complete this long-awaited chapter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 October 2017

I am currently readying myself for the push required to complete the final round of planting in the new garden. The outer wrap went in at the end of March to provide the frame that will feather the garden into the landscape and, with this planting still standing as backdrop, I have been making notes to ensure that the segue into the remaining beds is seamless.

The growing season has revealed the rhythms and the plants that have worked, and the areas where tweaking is required. Whilst there is still colour and volume in the beds I want to be sure that I am making the right moves. The Gaura lindheimerei were only ever intended as a stopgap, providing dependable flower and shelter for slower growing plants. They have done just that, but at points over the summer their growth was too strong and their mood too dominant, going against much of the rest of the planting. This resulted in my cutting several to the base in July to give plants that were in danger of being swamped a chance, and so now they will all be marked for removal. Living fast and dying young is also the nature of the Knautia macedonica and they have also served well in this first growing season. However, their numbers will now be halved if not reduced by two-thirds so that the Molly-the-Witch (Paeonia mlokosewitschii) are given the space they need for this coming year and the Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ the breathing room they require now that they have got themselves established.

Gaura lindheimerei

Gaura lindheimerei

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

Knautia macedonica with Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’

I will also be removing all of the Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ and replacing it with Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’. I was so very sure when I had them in the stock beds that both would work in the planting but, once it was used in number, ‘Swirl’ was too dense and heavy with colour. The spires of ‘Dropmore Purple’ have air between them and this is what is needed for the frame of the garden not to be arresting on the eye and so that you can make the connection with softer landscape beyond.

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’ (front) with Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album’ and Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ (behind)

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

The larger volumes of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ can be seen at the front of this image

As a gauzy link into the surroundings and as a means of blurring the boundary the sanguisorba have been very successful. I trialled a dozen or so in the stock beds to test the ones that would work best here. I have used Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ freely, moving them across the whole of the planting so their veil of tiny drumsticks acts like smoke or a base note. A small number of plants to provide cohesiveness in this outer wrap has been key so that your eye can travel and you only come upon the detail when you move along the paths or stumble upon it. Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’, perhaps the best of the lot for its finely divided foliage, picked up where I broke the flow of the ‘Red Thunder’ and, where variation was needed, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ has proved to be tireless. Smattered pinpricks, bright mauve on close examination but thunderous and moody at distance, are right for the feeling I want to create and allow you to look through and beyond.

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Sanguisorba ‘Cangshan Cranberry’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires

The gauze has been broken by plants that draw attention by their colour being brighter or sharper or the flowers larger and allowing your eye to settle. Sanguisorba hakusanensis (raised from seed I brought back from the Tokachi Millennium Forest) with its sugary pink tassels and lush stands of Cirsium canum, pushing violet thistles way over our heads. The planting has been alive with bees all summer, the Salvia nemerosa ‘Amethyst’, now on its second round of flower after a July cutback, and the agastache only just dimmed after what must be over three months ablaze. Agastache ‘Blackadder’ is a plant I have grown in clients’ gardens before and found it to be short-lived. If mine fail to come through in the spring, I will replace them regardless of its intolerance to winter wet, as it is worth growing even if it proves to be annual here. Its deep, rich colour has been good from the moment it started flowering in May and, though I can tire of some plants that simply don’t rest, I have not done so here.

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Sanguisorba hakusanensis

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Cirsium canum (centre) with Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires and Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

Agastache ‘Blackadder’

The lighter flashes of colour amongst the moodiness have been important, providing a lift and the key into the brighter palette in the plantings that will be going in closer to the house in a fortnight. More on that later, but a plant that will jump the path and deserves to do so is the Nepeta govaniana. I failed miserably with this yellow-flowered catmint in our garden in Peckham and all but forgot about it until I re-used it at Lowther Castle where it has thrived in the Cumbrian wet. It appears to like our West Country water too and, though drier here and planted on our bright south facing slopes, it has been a truimph this summer.

Nearly all the flowers in the planting here are chosen for their wilding quality and the airiness in the nepeta is good too, making it a fine companion. I have it with creamy Selinum wallichianum, which has taken August and particularly September by storm. It is also good with the Euphorbia wallichii below it, which has flowered almost constantly since April, the sprays dimming as they have aged, but never showing any signs of flagging.

Nepeta govaniana

Nepeta govaniana

Selinum wallichianum

Selinum wallichianum

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

I have rather fallen for the catmints in the last year and been very successful in increasing Nepeta nuda ‘Romany Dusk’ from cuttings from my original stock plant. I plan to use the softness of this upright catmint with the Rosa glauca that step through the beds to provide another smoky foil.

Jumping the path and appearing again in the planting that will be going in in a fortnight are more of the Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’. True to its specific name, this pretty, white calamint seems happy to seed around in cool places and I have used it, as I have the Eurybia diviricata, as a pale and cohesive undercurrent. They weave their way through taller groupings to provide an understory of lightness, breathing spaces and bridges. Both of these are on the autumn order and will jump again into the new palette I have assembled to provide a connection between the two.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 October 2017

Michael Isted is the founder of The Herball, a company producing handmade herbal infusions and plant extracts in small batches. The plants he uses to produce them are sourced from a number of independent, organic producers and freshness and quality are of prime importance. Michael started out as a drinks specialist and is a trained phytotherapist and nutritionist. He is passionate about educating and celebrating the ways in which we can integrate plants into our diets to energise, enhance and heal.

Michael, you have a background in the beverage industry. Can you tell us how you came to see the importance of plants and how that inspired you to start The Herball ?

I was always fascinated with nature growing up as a child in the cradle of the South Downs in Sussex, picking blackcurrants and sticking cleavers to people’s backs. Then, whilst working in the beverage industry as a drinks consultant, I realised that everything (almost everything) I was working with was made from plants, whether working with gin, vermouth, tea, coffee or distilling eau de vie. I knew I had to dedicate more of my time to learning from plants and from people that worked with plants. It all happened fairly organically, nature called and it felt like a brilliant path to tread, intuitively right.

Where did your passion for plants come from? Are there any key people, influences or experiences that set you on this path?

I think we all have a passion for nature, it’s just sometimes hard to access or connect with nature, particularly in our urban environments, but I’m sure inside of us all is a burning desire to be with nature in some form. Plants are so diverse, colourful, vibrant and dynamic on so many levels. They are extremely influential companions.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my earliest inspiration were the roses growing on the pathway leading up to our childhood house. That scent has stayed with me forever. The rose is a very powerful plant, it triggers so many memories. Like a form of time travel, it has taken me to some very magical times and places, it has been hugely influential.

Then I was inspired by learning about distilling plants with an eau de vie distiller in Alsace and connecting with herbalists such as Peter Jackson Main, Peter Conway, the work of Barbara Griggs and for sure the writing of Stephen Harrod Buhner. I urge everyone to read his book The Lost Language of Plants.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Dehydrator trays containing (clockwise from top left) dried nettle, cleavers, equisetum, elderflower and gingko.

Photo: Susan Bell

You are a qualified Phytotherapist. Can you explain what that means and what the training involves?

It’s a posh term for a herbalist, to make us sound more professional. It means somebody who works with plants to heal and nurture people. We introduce nature and look at ways in which plants can help support disease, illness or just enrich people’s lives.

I trained with many naturopaths, nutritionists, herbalists and plant workers on shorter courses and then went into a full time BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Westminster. It took four years of full time training, but some of the most valuable training is spending time with the plants themselves. They can teach you a great deal.

Tell us about the range of products you produce, and the process you went through to develop them.

It all started as I was unhappy with the quality of the herbs & spices in many herbal teas and commercial spice ranges. There was (is) a distinct lack of relationship between people and the plants that they are drinking or eating. Supermarkets are littered with herbs in tea bags and boxes, but you don’t see the plants or engage with them enough. You don’t know where they are from, when they were harvested, who harvested them, you can’t even see the plants. So I wanted to create a range of plant products where you could really engage with the plant itself, on a very basic level by looking at and identifying it, drinking its qualities. It’s about engaging with and respecting nature really. I want people to see the love and hard work (from both the plant and the people producing them) that goes into nurturing, growing, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs.

We take plants for granted most of the time. Just take black pepper for example. In almost all households it is just a commodity. It’s just not celebrated enough. It’s a sensational plant, with brilliant flavour. Just take a good quality black peppercorn and place it in your mouth and eat it. Taste it fully and consider its qualities. Phenomenal.

We really want people to engage with the nature that they are drinking, eating and ingesting. All of our plants are harvested in that growing year, we know when they were harvested and by whom. We make our infusions, waters and bitters in tiny batches. It’s all created by hand with lots of care using the most vibrant plant material possible.

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

The Herball’s Of Aromatic Waters

Our aromatic waters (non-alcoholic distillations of plants) were sourced from two distillers in the UK and India, although we have since stopped working with them as we are now distilling everything ourselves. There will be some very special distillates available in 2018 as we are currently working on polypharmic distillations, distilling lots of different plants at the same time. There is a natural synergy between plants in the wild and it’s always interesting to see which plants like to grow together, for example nettle & cleavers. We are trying to capture this synergy and relationship in the form of a distillation.

We distil plants in traditional copper alembic stills (main image – photo by Susan Bell) to use as a flavouring for food and drinks and as ingredients for natural skin care. We are just starting to use CO² extraction, which produces the most beautiful and vibrant oils. We also work with co-operatives in Southern India and Sri Lanka who supply us with beautiful vibrant spices. Again it is crucial that we know who harvested the plants, where and when. We visit the growers on their tiny holdings – when I say tiny they are really tiny, 1 hectare and less – and they cannot afford organic certification, so that’s where the co-operative comes in, to help give the growers the sales platform and access to people like us.

The bitters are remedies and recipes that I had been using in practice and for drinks creation for years. They cover all of my inspirations, so there is an English-based blend with 20 herbs grown here, an Indian blend with spices like cinnamon, turmeric and one of my favourite bitter herbs, Andrographis, and a Chinese blend with Chinese herbs such as Schisandra paired with a beautiful rock oolong tea from our dear friends at Postcard Teas. We wanted to share these formulas with everyone.

From where and how do you source your ingredients?

The herbs we use are mostly grown, nurtured, harvested and dried by a wonderful grower called Diane Anderson who has a smallholding in Oxted, Surrey. Diane was one of my teachers at University. She was an amazing resource and she used to come into the dispensary with the most beautiful dried herbs. Seeing these wonderful dried herbs was also an inspiration to start blending infusions.

We also work with a biodynamic plantation in Somerset, we grow a few things ourselves and for the more exotic plants, as mentioned before, we source from our friends in Southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cardamom

Cardamom

Turmeric

Turmeric

Can you explain how the bitters and herbal waters you produce might be used?

I’m not allowed to talk too much about the health benefits of our products, so broadly speaking their purpose is really to enhance and envigorate drinks and dishes and to give pleasure. The bitters are amazing just with water, or fresh juice, pre- and post-prandial, to stimulate digestive function and assimilate some of the metabolites from your meal. The aromatic waters are so diverse, I use them every day in a glass of water, sprayed directly on my face as a toner (rose), in salad dressings (rosemary & thyme are particularly good), to create cocktails with and without alcohol. They are amazing.

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

The Herball’s Of Ayurveda Bitters

Can you tell us something of the therapeutic effects of some of your key ingredients?

Plants have endless therapeutic qualities on so many levels, physically, spiritually, emotionally, and I think it’s important that you are ingesting some good quality organic plants every day. I don’t want to say as part of a routine as that sounds boring, but use them prophylactically as a preventative. Have fun with plants, get to know them, enjoy their nature, enjoy their brilliance, it’s so rewarding for health and happiness.

The herbs we use and work with are packed full of complex secondary metabolites, diverse plant chemicals (phytochemicals) produced by the plants which enable the plants to interact with their environment. These phytochemicals have a wide range of functions, including protection from herbivores, to fight against infections and to attract pollinators such as bees and other insects. The plant’s secondary metabolites include constituents such as tannins, aromatic oils, alkaloids, resins and steroids. It is these chemicals that not only carry a raft of potential health benefits for us, but also offer a huge palette of flavours, textures and aromas to create delicious food and drinks.

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

The Herball’s Of Herbs infusion contains marshmallow, peppermint, red clover, wormwood, burdock, lemon balm , rosemary, yarrow, goats rue and fennel

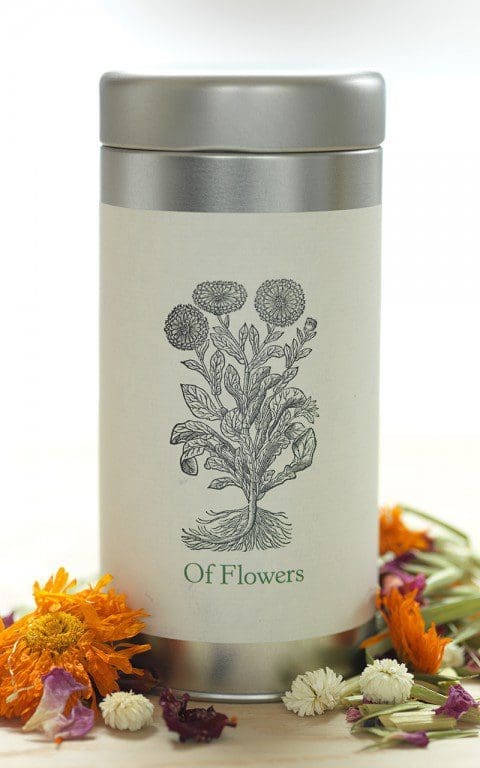

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

The Herball’s Of Flowers infusion contains oat straw, Roman chamomile, calendula, rose, lavender and goldenrod

You have a book coming out in the new year. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Super exciting, yes. It’s a book on my work really. I talk about my inspirations, some of the plants that I work with, when and how to harvest them and then how you can work with those plants to create dynamic and delicious botanical drinks. I talk about distillation, extraction methods, drying and processing the plants and then there are over fifty recipes, all without alcohol.

Would you share a recipe with us that readers can try at home?

Sure. I’m drinking a lot of sage right now so here is a simple recipe with sage including a quote from John Gerard, whose work we have been greatly inspired by, he wrote (or collated and published) the seminal text The Herball or Generall historie of plantes, 1597.

THE WISE ONE

‘Sage is singularly good for the head and brain, it quickeneth the senses and memory, strengtheneth the sinews, restoreth health to those that have the palsy, and taketh away shakey trembling of the members’. John Gerard 1545 – 1612.

Photo: Susan Bell

Photo: Susan Bell

This is a contemporary take on a classic sage preparation to produce a cooling, blood cleansing formula, which makes for a sensational afternoon tipple.

Plants & Ingredients

Sage Salvia officinalis

Lemon Citrus limon

Sugar Saccharum officinarum

Water

Recipe

15g fresh sage

4 lemons

500ml hot water

75ml lemon & sage sherbet (see below)

100g sugar

Method

Boil the water, then pour over 10g of sage into a pot with a lid. Infuse with the lid on for 30 minutes before straining into another jug or decanter. Peel 1 of the lemons and keep the zest. Add the juice of that lemon and the sherbet to the decanter and stir until dissolved. Keep the jug or decanter in the fridge to chill and serve once cold.

Serve in a wine glass with the remaining twist of lemon and fresh sage leaves

For the Sherbet

Peel the remaining 3 lemons, then put the zests in a container with the sugar and the remaining 5g of sage. Press the zests with the sugar and sage for a minute or so, then juice the lemons and stir the juice into the sugar mixture. Seal and leave to infuse overnight, or for at least 6 hours. Stir, strain and bottle. This will keep refrigerated for at least 1 month and can be enjoyed with still and sparkling water.

The Herball’s Guide to Botanical Drinks: A Compendium of plant-based potions to Energise, Cleanse, Restore, Boost Sleep and Lift the Heart by Michael Isted, photography by Susan Bell, will be published by Jacqui Small in February 2018. Pre-order here.

Twitter: @TheHerball

Instagram: theherball

Interview: Huw Morgan/All other photographs: Laura Knox

Published 30 September 2017

For the first three or four years here we grew row upon row of dahlias in the old vegetable garden. They soaked up the light in the first half of summer and flung it back again in a riot of colour later. We grew upwards of fifty, with rejects making way for new varieties from one year to the next to test the best and the most favoured. The dahlias were completely out of character with what I knew I wanted to do here but, like children in a sweetshop, we had the space to play and so we indulged.

Three years of experimentation left us gorged and satiated, but a handful made it through to become keepers. All singles, and delicate enough to be worked into the naturalism of the new planting, we kept Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’ for sheer stamina of performance, Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’, the most delicate of all, and the demurely nodding Dahlia australis. Proving to be perfectly hardy with a straw mulch as insurance against the cold they have made good garden perennials. The exception is a scarlet cactus dahlia that outshone the blaze of competition in the trial. Originally bought as ‘Hillcrest Royal’, but mis-supplied, we grew it in our old garden in Peckham and loved it enough to bring it with us and, then again, to keep it in the cutting garden. Unable to identify it correctly after many years of sleuthing we named it ‘Talfourd Red’ after the south London road we lived on and I cannot imagine an autumn now without its flaring fingers.

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

Dahlia ‘Talfourd Red’ and Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter’

I do like a new plant, and getting to know Tithonia rotundifolia for the first time this year is enabling me to see how it might be used to inject some late summer heat into a planting. We already have a handful of favourites here that are tried and trusted and loved for their intensity of colour, which builds as the growing season wanes. In the case of the Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’, they are almost at their best sprawling and vibrant in the damp cooling days and allowed to climb into their neighbours. The seed originally came from the garden of Mien Ruys at least twenty years ago. I had gone with two friends on an inspirational trip to see what was happening in naturalistic gardens in Holland and Germany and we stopped to meet her in her wonderful garden. The seed was scattered on the pavement over which it was sprawling and a few found their way, with her consent, into my pocket.

This ‘Mahogany’ is not what you will get if you look for it in the seed catalogues. Indeed, it now seems to be unavailable apart from in the United States and ‘Mahogany Gleam’ is a different thing altogether. The leaves are a brighter more luminous green than usual and the flowers a jewel-like ruby red. I have been territorial ever since I started to grow it and winkle out any that come up with a darker leaf or paler flower. It self-seeds willingly every spring, letting you know when the soil is warm enough to sow and where the warmest parts of the vegetable garden are. The seedlings exhibit the same bright foliage so it is easy to weed out the occasional rogue, which might have reverted to the darker more typical green. We currently grow ‘Mahogany’ in the kitchen garden amongst the asparagus and use the leaves and flowers to garnish salad.

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tithonia rotundifolia ‘Torch’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Close by, and growing this year in two old stoneware water filters, is Tagetes patula. This wild form will grow up to three or four feet with a little support or something to lean on and flowers from June until it is frosted. The colour is absolutely pure and as vibrant and saturated a saffron yellow as you can find. It is easily germinated from seed under cover in spring and fast, so best to wait until mid-April to sow. I harvest my own seed and keep it apart from the dark, velvety Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’ (main image), which it will taint. Seedlings that have crossed will no longer have the deep richness that makes this latter plant so remarkable. I was disappointed to find this spring that the mice had eaten all the seed I’d left out in the tool shed and was expecting to have the first of many years without it. However, as luck would have it and quite out of the blue, they somehow found their way some distance into the new herb garden. Maybe it was mice doing me a favour with the plants I left standing in the kitchen garden last winter. Another lesson learned.

Tagetes patula

Tagetes patula

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Tagetes ‘Cinnabar’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

My father was never afraid of colour and always commented on the brilliance of Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’, which is the best, most brilliant red I have ever come across. Purer for the flowers being properly single, with elegant tear-shaped petals and thrown into relief against darkly zoned foliage. I bought a tray of plants from Covent Garden Market twenty five years ago for my Bonnington Square roof garden and have managed to keep them going ever since. Given how archetypal it is for a pot geranium I have no idea why it is not more freely available, but there are always a handful of cuttings in the frame which are for giving away to friends, who are given these precious things on the understanding they are part of keeping a good thing going, and that they are my insurance for any unexpected losses.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 September 2017

One of the best things about growing your own fruit and vegetables is the opportunity it provides to eat things that are seldom, if ever, available at the greengrocers. Before we planted our orchard I had never eaten a Mirabelle plum. Although I had pored over Jane Grigson’s description of their superior flavour, and heard from my Francophile friend Sophie of the delicious tarts and pies she had eaten in Lorraine, I had always had to imagine what they tasted like.

The Mirabelle is the smallest plum, barely bigger than a large marble, but what it lacks in size it definitely makes up for in flavour. Perfumed, and with the same floral hint of muscat that you get from the best gooseberries, they are the plum par excellence. We are now getting a very decent harvest and, when something so rare and prized suddenly becomes easily available, it feels important to celebrate the moment with a dish that makes the most of this fleeting moment.

You need a fair number of Mirabelles to make a tart of this size, but they are quick to pick. De-stoning a large bowl of them also appears an intimidating prospect but, being a ‘freestone’ variety of plum, where the stone separates easily from the flesh (unlike ‘clingstone’ plums where the flesh adheres to the stone) they are also easy to prepare.

Plums and almonds are all from the Prunus family, and so make perfect companions in in desserts. The flavour of the almond frangipane is improved by the addition of a number of kernels taken from the stones, which enhances the bitter almond flavour, but a few drops of almond essence or, if you happen to have it, a teaspoon or two of plum eau de vie do a similar job.

The Mirabelle season is painfully short. The tart here was made last weekend, when the plums were at their peak of perfection. This week the tree is bare. So, if you have missed the moment or can’t get hold of them, you can use any other stone fruit in their stead. Greengages are the next best choice of plum, but other yellow cooking plums would work, as would apricots. Later in the season the frangipane can be made with ground walnuts, which makes a more autumnal partner for sharp red or purple plums. This year I plan to try a walnut version with some of our damson glut but, being mouth-puckeringly sharp, they will need to be poached in a sugar syrup first.

Mirabelle de Nancy

Mirabelle de Nancy

INGREDIENTS

500g Mirabelle plums, stoned and halved (weight after stoning)

Pastry

300g plain flour

150g unsalted butter, well chilled

3 tbsp icing or caster sugar

1 egg yolk, beaten

Iced water

Almond Cream

150g ground almonds

150g caster sugar

150g butter, melted

1 large egg, beaten

2 tbs double cream

Kernels from about 20 Mirabelles

Serves 12

METHOD

You will need a 30cm shallow, fluted tart tin.

Set the oven at 180°c.

Put the flour and butter into a food processor and process quickly until the mixture resembles very fine breadcrumbs. You can use your hands to do this, but a processor is better as it is important that the pastry stays as cold as possible. Add the icing sugar and pulse again quickly to combine. With the motor running add the egg yolk, and then enough chilled water, a tablespoon at a time, until the dough just starts to come together. Immediately turn off the processor and bring the dough together quickly and lightly with your hands until smooth. Do not knead it.

Immediately roll the dough out, preferably on a cold, floured slate or marble surface, with short, light movements until just large enough to line the tin. To get the pastry, which is very short, into the tin, ease your floured rolling pin underneath it and then very gently lift it over the tart tin until it is centred, before removing the rolling pin by sliding it out. Again handle the pastry very gently as you press it into the corner and fluted sides of the tin. Trim the pastry in line with the top of the tin, prick the base with a fork and then chill in the fridge for 20 minutes.

Remove the pastry case from the fridge, line it with baking parchment and then fill with baking beans. Bake blind for 20 minutes. Remove the baking beans and parchment and return to the oven for a further 10-15 minutes until the pastry looks dry but has not coloured. Remove from the oven and leave to cool.

Turn the oven up to 200°c.

Put the ground almonds and sugar in a mixing bowl, reserving a tablespoon of sugar. In a mortar and pestle crush the Mirabelle kernels with the tablespoon of sugar then add them to the ground almonds, before mixing in the butter, egg and cream.

Spread the almond cream evenly over the base of the cooled tart case. Then, starting from the outside, arrange the Mirabelles on the almond cream with their cut sides facing up and so that they are just touching. Push each one gently into the cream as you do so.

Bake for 30-40 minutes, until the pastry is well coloured and the mirabelles are bubbling.

Remove from the oven. Allow to cool for 15 to 20 minutes before carefully removing from the tart case.

Serve warm with cold pouring cream.

Recipe and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 2 September 2017

We always grow too many pumpkins. Such has been the luxury of having the space to do so. They have found themselves in a different position every year to give them the opportunity to reach. In the first summer they were in the virgin ground where we had turned field over to garden and the flush of weeds that had been disturbed by the change were kept in check by their coverage. The next year they were out in front of the house, each plant perched on a barrowload of muck on the banks. But it was too exposed there, we had a wet summer and learned their limits, for they made not much more than leaf. The disappointment of not having them in storage lasted the whole winter. Consequently, as the best way to learn is by your mistakes, I have taken their needs more seriously.

Six summers’ worth of trial, error and experimentation have taught us the good producers, the best keepers and those that under-produce in relation to their enormous appetite for space. A Californian friend and gardener, who grows the giant pumpkins you only find in the country where everything is bigger, was amazed that I was giving my plants so little room to grow. His pumpkin patch is the size of my whole garden, so he was not surprised that I hadn’t done better in terms of size and yield. A big plant with a rangy nature can easily take over a plot of nine or more square metres to provide the optimum ratio of leaf to fruit and, now that I have started planting up the garden, space for pumpkins is becoming more limited. So next year’s selection is due an edit. The giants will be separated from those that are happy with less space and the neater, more economical growers will have a bed to themselves in the kitchen garden with plenty of muck and sunshine. The big growers will be given the top of this year’s compost heap so that they can enjoy a romp and tumble over the edges unencumbered.

‘Musquée de Provence’

‘Musquée de Provence’

Of the big growers that produce more leaf than fruit, we will not be growing ‘Musquée de Provence’ again, after three years of trying. The deep-green, lobed fruit, though handsome, are supposed to ripen to a rich tan colour, but even on our south-facing slopes we just don’t have enough sun to do so. Consequently, the skin doesn’t cure fully and they have been poor keepers. Our average of one fruit per plant is also not worth the investment of space. Although a single pumpkin can easily feed twelve, there are only so many times you require a pumpkin that large.

‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’

‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’

‘Crown Prince’

‘Crown Prince’

We have had a similar experience this year with ‘Rouge Vif d’Étampes’, another French variety with large fruits of a strong red-orange. It also appears to need more heat to crop heavily and ripen fully. These two have been the first to be eaten, as we try and keep pace with the rot. All pumpkins and squash like heat and good living and our cool, damp climate sorts out those that are clearly missing the Americas. In contrast, ‘Crown Prince’ has been more adaptable here and one of the best croppers for a plant that needs space. It is also an excellent keeper. The saffron flesh is firm and sweet while the thick, grey-green skin means that they can keep into March in a cool, frost-free shed.

The varieties with dry, firm flesh are better for storing than the wetter ones, which I presume is due to their higher sugar content. We also prefer them for eating. Of the smaller growing varieties we have found the Japanese pumpkins to be the most consistent, with the highest yield for their economical growth and the most delicious flesh. They produce fruit of a moderate size, which is far more convenient to eat than opening up a Cinderella-sized pumpkin that feeds a horde and then sits on the side, the remainder unused, making you feel guilty.

‘Uchiki Kuri’

‘Uchiki Kuri’

Of the Japanese varieties ‘Uchiki Kuri’, or the red onion squash, is the one you see most often in Japan and the one I will eat on an autumn visit to Hokkaido where it is grown extensively. It is a moderate grower, with smallish foliage and an even and reliable yield, with each plant producing 8 or more 1-2kg pumpkins. The deep orange teardrop-shaped fruit are small enough to provide for one family meal and, with a good balance of flesh to seed, there is little waste. Kuri means chestnut in Japanese, and the flavour and texture of this and the other kuri varieties explains why. They are excellent baked, with a rich, floury texture that also makes superlative mash and soup with plenty of body.

‘Cha-cha’

‘Cha-cha’

Kabocha is the Japanese word for pumpkin, derived from the corruption of the Portugese name for them, Cambodia abóbora, since they were brought to Japan from Cambodia by the Portugese in the 16th century. This year we grew ‘Cha-cha’, which closely resembles ‘Blue Kuri’, a Japanese kabocha variety we have previously had success with. It has also proven to be very good. Slightly larger than ‘Uchiki Kuri’ the flesh is also dry, rich and sweet, and the thin skin is edible when roasted.

‘Black Futsu’

‘Black Futsu’

‘Black Futsu’, another Japanese variety with sweet, nutty flesh, is of a similar size. The fruits are heavily ribbed and dark, black-green when picked, quickly developing a heavy grey bloom, beneath which they ripen to a tawny orange. Though beautiful to look at, the ribbing does mean they are more work to cut and peel, but it is a small hardship in terms of yield and substance.

‘Delicata’

‘Delicata’

Another heavy cropper, although not such a good keeper, is ‘Delicata’, also known as the sweet potato squash due to it’s mild, sweet flesh which is moister than the varieties described above. Although kept and eaten as a winter squash ‘Delicata’ is of the summer squash species with a very thin skin (hence its name) and so has a propensity to soften quickly in storage. However, it needs no peeling as the skin is edible, so it has its uses in the earlier part of the season. The beauty of this very decorative variety is its high yield of long, cylindrical fruits (perfect for stuffing) in a range of manageable sizes, some the perfect size for one, which makes it a very practical choice.

Although in the past I have let the first frost strip the summer foliage before harvesting, it is best to remove it by hand in September when the plants have done their growing and there is a little heat left in the sun to do a final ripening. It is best to pick the fruits before they get frosted or they don’t keep well, and care must be taken not to damage the hard, waxy skin which keeps them airtight through the winter. The stalks should be left intact for the same reason, as any wound quickly leads to rot.

Left in a warm, sunny place for a couple of weeks after picking the carbohydrates in the flesh turn to sugar and the skin hardens. The colour also changes, but this continues to develop in storage. When ripe they should be stored in a shed or outhouse on wire racks or a bed of straw to allow air to circulate beneath them. For now, I have them on old palettes in an airy barn, but when it gets colder they will be put into perforated plastic plant trays and moved to the frost-free tool shed.

We are gradually making our way through this year’s crop with roast, mash, soup and finally preserves, before the rot sets in. It nearly always does and, although the decay has its own beauty, I’d rather not waste a summer of effort. Both ours and the pumpkins’.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

It has been an exciting autumn, and one that I have looked forward to and been planning towards for the past six years. It has taken this long to resolve the land around the house. First to feel the way of the place and then to be sure of the way it should be.

Though the buildings had charm, (and for five years we were happy to live amongst the swirly carpets and floral wallpapers of the last owner) the damp, the white PVC windows and the gradual dilapidation that comes from years of tacking things together, all meant that it was time for change. Last summer was spent living in a caravan up by the barns while the house was being renovated. We were sustained by the kitchen garden which had already been made, as it provided a ring-fenced sanctuary, a place to garden and a taste of the good life, whilst everything else was makeshift and dismantled.

This summer, alternating between swirling dust and boot-clinging mud, we made good the undoings of the previous year. Rubble piles from construction were re-used to make a new track to access the lower fields and the upheavals required to make this place work – landforming, changes in level, retaining walls and drainage, so much drainage – were smoothed to ease the place back into its setting.

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

The newly fenced ornamental garden and the new track to the east of the house viewed from The Tump

Of course, it has not been easy. The steeply sloping land has meant that every move, even those made downhill, has been more effort and, after rain, the site was unworkable with machinery. We are fortunate that our exposed location means that wet soil dries out quickly and by August, after twelve weeks of digger work and detail, we had things as they should be. A new stock-proof fence – with gates to The Tump to the east, the sloping fields to the south and the orchard to the west – holds the grazing back. Within it, to the east of the house and on the site of the former trial garden, we have the beginnings of a new ornamental garden (main image). An appetising number of blank canvasses that run along a spine from east to west

The plateau of the kitchen garden to the west has been extended and between the troughs and the house is a place for a new herb garden. Sun-drenched and abutting the house, it is held by a wall at the back, which will bake for figs and cherries. The wall is breezeblock to maintain the agricultural aesthetic of the existing barns and, halfway along its length, I have poured a set of monumental steps in shuttered concrete. They needed to be big to balance the weight of the twin granite troughs and, from the top landing, you can now look down into the water and see the sky.

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The end of the herb garden is defined by a granite trough, with the shuttered concrete steps behind

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

The sky, and sometimes the moon, are reflected in the troughs

On the lower side of the new herb garden, continuing the bank that holds the kitchen garden, the landform sweeps down and into the field. Seeded at an optimum moment in early September, it has greened up already. Grasses were first to germinate, and there are early signs of plantain and other young cotyledons in the meadow mix that I am yet to identify. I have not been able to resist inserting a tiny number of the white form of Crocus tommasinianus on the brow of the bank in front of the house. There will be more to come next year as I hope to get them to seed down the slope where they will blink open in the early sunshine. I have also plugged the banks with trays of homegrown natives – field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and divisions of our native meadow cranesbill (Geranium pratense) – to speed up the process of colonisation so that these slopes are alive with life in the summer.

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Seeding the new banks in front of the house in September

Below the house, the landform divides to meet a little ha-ha that holds the renovated milking barn and a yard which will be its dedicated garden space. This barn is our new home studio and from where I am planning the new plantings. I have placed a third stone trough in this yard – aligned with those on the plateau above – with a solitary Prunus x yedoensis beside it for shade in the summer. There are pockets of soil for planting here but, beyond the two weeks the cherry has its moment of glory, I do not want your eye to stop. This is a place to look out and up and away.

That said, I have been busily emptying my holding ground of pot grown plants that have been waiting for a home, and some have gone in close to the milking barn to ground it; a Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Gingerbread’ from the old garden in Peckham, a Paeonia rockii, a gift from Jane for my 50th, and the beginnings of their underplantings, including Bath asparagus and some favourite hellebores that I’ve had for twenty years or more. The spaces here are tiny and they will need to work hard so as not to compete with the view out, nor disappoint when you get up close on your way to the barn. The bank sweeps up to wrap the milking barn above and to the east and the planting with it, so that it is nestled in on both sides. Below the barn there is the contrast of open views out into the fields, so when inside I can keep a clear head from the window.

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Planting the Prunus x yedoensis in the milking barn yard in July

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

Plants laid out on the edge of the ha-ha in November

To help me see my new canvasses in the new ornamental garden clearly I have started dismantling the stock beds. The roses, which have been on trial for cutting, will be stripped out this winter and the best started again in a small cutting garden above the kitchen garden. I’ve also been moving the perennials that prefer relocation in the autumn. Jacky and Ian, who help in the garden, spent the best part of a day relocating the rhubarbs to the new herb garden. It is the third time I have moved them now (a typical number for most of my plants), but this will be the last. In our hearty soil, they have grown deep and strong and the excavations required to lift them left small craters.

The perennial peonies, which go into dormancy in October, also prefer an autumn move, as do the hellebores so that their roots are already established for an early start in the spring. They both had a firm grip and I had to lift them as close to the crowns as I dared so that they were manageable. The hellebores have been found a new home in a rare area of shade cast by a new medlar tree that I planted when the landscaping was being done. I rarely plant specimen trees, preferring to establish them from youngsters, but the indulgence of a handful, which included the cherry and a couple of Crataegus coccinea on the upper banks near the house, have helped immeasurably in grounding us in these early days. To enable a July planting these were all airpot grown specimens from Deepdale Trees which, as long as they are watered rigourously through the summer, establish extremely well. Usually right now is my preferred (and the ideal) time to plant anything woody.

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting up the area behind the milking barn with the new medlar in the background

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

Planting seed-raised Malus transitoria in the new garden in October. In the background are the trial and stock beds, which are gradually being dismantled. The best trial plants will be divided and used in the new plantings.

It is such a good feeling to have been planting things I have raised from seed and cuttings for this very moment; a batch of seedlings grown on from my Malus transitoria to provide a little grove of shade in the new garden, rooted cuttings of Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’ to screen the new garden from the field below, and a strawberry grape (Vitis vinifera ‘Fragola’), a third generation cutting from the original given to me thirty years ago by Priscilla and Antonio Carluccio, is finally out of its pot and on the new breezeblock wall. Close to it I have a plant of the white fig (Ficus carica ‘White Marseilles’), a cutting from the tree at Lambeth Palace, where I am currently working on the landscaping around a new library and archive designed by Wright & Wright Architects. The cutting was brought from Rome by the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Reginald Pole, in 1556. In 2014 a cutting made the return journey to Pope Francis, a gift of the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. The tree reaches out from the palace wall in several directions to touch down a giant’s stride away. It is probably as big as our little house on the hill, and my cutting is full of promise. It is so very good, finally, to be making this start.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan, Dan Pearson & Jacky Mills

I try hard to ensure that these posies picked from the garden are done in real time, but last weekend I flew off to the States for a week’s work. So this bunch I picked last Saturday before the frost, which till then had kept itself to the hollows down by the stream, made its way up into the garden for the first time on Sunday morning. These are the very last of the dahlias, pushing against the tide of decay, but dwindling daily with the increasing cold at night. Blackened the instant the frost arrives and heralding the coming of winter.

Usually this is the time to lift dahlias. The tender foliage is seared back to the stem. Dig down and the fleshy tubers are rude with a summer’s feeding and full of the energy they need to sustain them through the winter. The two species I have selected here have so far proven themselves to be just as happy in the ground with a little help in the form of a mulch of compost to keep them through the cold season.

Dahlia australis

Dahlia australis

Despite the elegance of its finely divided leaves and sharply drawn flowers, Dahlia australis is a plant that needs room at the root in company. Try to lift the tuber and you find that it is easily a two-man job and this is why the push of growth is strong and constant from the moment it comes through in the spring.

Standing now at shoulder height and a stretch of the arms across this is not, however, a plant that feels demanding of space. With delicate growth and single flowers on wiry stems, there is a lightness about it that tends to be lost in the hybrids. For this reason I have decided to keep it in the garden as it will sit well with the wild feel of its companions. I plan to have it amongst Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’, which you can see here at the very end of its flowering season. The tiny violet flowers, which leave behind them a sterile taper, have been flowering for months, but now have nowhere left to go. Three or four plants spread widely in a bed provide a vertical accent and the dahlia will be good pushing its way through this floral cage.

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Amsonia hubrichtii

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Amsonia hubrichtii

Dahlia merckii ‘Alba’ is of an altogether lighter weight and more delicate disposition. Standing at no more than chest height, with delicate growth and foliage, this is a delectable dahlia. Despite its appearance, it seems to be perfectly hardy, and I would not want to be without it for its constancy of flower. These are pure white, small and widely-spaced and dance like butterflies in wind, but if the plant is not in good company it will snap and break. Teaming it with low perennials that will not overwhelm its foliage is better than staking. Far less fiddly and better for the dahlia to find its own way, since the spaciousness in the plant comes out in several directions from the crown. In the stock beds I have it with a herbaceous Salvia pratensis, but when I use it in the new garden I will team it with the Amsonia hubrichtii that you see colouring gold in this posy. They are both sun loving and, after its early flower, the amsonia will leave room for the dahlia to get away in the first half of the growing season.

The flowers of both these dahlia species die well by simply dropping their petals and, as they seem happy to continue to produce without throwing all their energy into seed, there is no need to dead head as you might their more flamboyant relatives. The singles also have the added benefit of being accessible to pollinating insects.

Bronze fennel (Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’)

Bronze fennel (Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’)

Miscanthus ‘Dronning Ingrid’ and Bronze fennel (Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’)

Miscanthus ‘Dronning Ingrid’ and Bronze fennel (Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’)

I have included the bronze fennel in the bunch for its darkness now that it is in seed and the miscanthus for its ability to harness the light in its inflorescence. I am finding the miscanthus difficult to place in the garden because they have such a strong atmosphere which smacks too much of somewhere else to sit easily in this landscape. I have seen them growing wild in Japan, where their plumage is the emblem of the autumn season and their clumps illuminate autumnal verges. Miscanthus sinensis ‘Dronning Ingrid’ is a new variety to me with foliage that colours with flashes of red and orange at the end of the season. The flowers, which are not as dark as some but emerge with a red flush nonetheless, soon pale to silvery bronze. The flower, held free to catch the breeze, is more tapering than many miscanthus but, come the winter, it lives up to its common name of Silver Grass as it flares in the low light.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

This is the third year of my aster trial and a good point to judge how they have performed. The collection, which I set up to broaden my palette, has scratched the very tip of an iceberg, which must run to hundreds of varieties. I currently have just twenty-six and I am at the point now of wanting to reduce them to a dozen or so. Some I have grown before, but the greater number have been selected from plant fairs and on trips to see the well-known collections at Waterperry Gardens and the Picton Garden.

Asters are some of the best late-flowering perennials, the first flowers to hint at the next season in late August, and some of the very last to see the autumn out, their flowers hanging in suspension as the colour drains from everything around them. Aster borders were once celebrated in Victorian and Edwardian gardens, but they became unpopular for a period and with good reason. Many of the older varieties were prone to mildew and those that run could take a border over in the same time that I have been running my trial. I suspect this is one of the reasons that you see them naturalised along railway embankments, where they were thrown over garden fences in frustration, and where the strongest can compete with the buddleia and brambles.

Frustratingly, asters have recently been renamed; A. novae-angliae, A. novi-belgii, A. laevis, A. dumosus, A. lateriflorus, A. cordifolius and A. ericoides have become Symphyotrichum, while A. divaricatus and A. schreberi are now Eurybia. Whatever you call them, aster enthusiasts and nurserymen who are selecting and naming new varieties have honed them for their mildew resistance. This means that in the summer wait for their moment of glory, they help provide a sense of healthy expectation in the borders. They have also been selected for their clump-forming ability and the majority stay put until they need division. Depending upon the variety, this can be in four to six years. They show you when they need this by developing a monkish bald patch in the middle. Division of the strongest growth to the outer edges in the spring renews their vigour.  The aster trial with from left to right, A. ‘Vasterival’, A. ‘Calliope’, A. ‘Violetta’ and A. ‘Primrose Path’

The aster trial with from left to right, A. ‘Vasterival’, A. ‘Calliope’, A. ‘Violetta’ and A. ‘Primrose Path’

As I write, the sun is streaming down the valley at an ever-decreasing angle, having burned its way through a morning mist. We had the first frost in the hollows today, so I would say this was perfect weather for looking at my collection. In the penultimate week of October they are in their prime and they look their best in the softened light with the garden waning around them. I have spent the morning amongst them, taking notes and pushing my way through the shoulder high flower to trace them from top to bottom. I want to see if they have stayed put in a clump, and which ones can do without staking, as I’m aiming for there to be as little of that here as possible.

I am smarting, however, as I have committed the ultimate sin when running a trial, for six of the labels are missing, buried within the basal foliage (I’m hoping) or – less helpfully – snapped off when weeding. Of these six I am going to keep two that have shown themselves to be special and, through a process of elimination from studying photographs and my garden diary, I will find out what they are. The others will be found a metaphorical railway embankment. In this case a rough patch of ground where the sheep won’t get them, but where they can provide some late nectar for the bees.

I have just a small number of creeping varieties which I tolerate for their informality. Although most asters prefer to be out in the open with plenty of light, the first three here are happy to live under the skirts of shrubs or in dappled shade. Aster divaricatus, a plant that Gertrude Jekyll famously used to cover for the naked patch the colchicum foliage leaves behind in summer, is one of my favourites. I have seen it in North American woodland where it lives happily amongst tree roots and spangles the dappled forest floor in autumn. Although it will not dominate here, as it does in the States, and runs slowly, it does move about, the dark, wiry stems leaning and sprawling and pushing pale, widely-spaced flowers to a foot or so from the crown. Aster schreberi is similar to look at, with single starry flowers, though it is stronger and has taken off in my hearty soil. I will put it amongst hellebores, which should be man enough to fight it out in the shade under the hamamelis. I will let you know who wins in a couple of years.

Aster ‘Primrose Path’

Aster ‘Primrose Path’

Strictly speaking, I should be wary of Aster ‘Primrose Path’ for not only does it double itself in size every year, it also seeds. However, it is not a hefty plant, growing to just 75cm and, as it is also happy in a little shade, I am keen to keep it and use its ability to move around in the shadier parts of my gravel plantings around the barns. The flowers, which are small, but not the smallest, are a delicate lilac, each with a lemon-yellow centre.

Aster ‘Violetta’

Aster ‘Violetta’

Aster ‘Little Carlow’

Aster ‘Little Carlow’

Aster ‘Coombe Fishacre’

Aster ‘Coombe Fishacre’

Most of the asters for the new garden have been selected for lightness of growth and flower, as I want the plantings to be transparent, allowing views of the far landscape into the garden. All, with the exception of the semi-double ‘Violetta’, are single. I like to see the centre of the flowers and I want them to to dance or to sit like a constellation in space rather than blaze in a solid mass like ‘Little Carlow’. Growing to well over a metre for me here, this is a really good plant, needing little staking and being thoroughly reliable, but it is too floriferous for me, the flowers bunched tight with little space between them so that the weight of flower seems impenetrable. ‘Coombe Fishacre’, though also densely flowered, is certainly a keeper, the centres of the soft pink flowers age to a darker grey-pink to throw a dusky cast over the whole plant. It is good for being shrubby in appearance and self-supporting.

Aster turbinellus hybrid

Aster turbinellus hybrid

My absolute favourite Aster turbinellus (the Prairie Aster), is one of the latest to flower, its season running from October into November if the weather holds out. It is exquisite for the air in the plant, the foliage being reduced to narrow blades and the stems wiry and widely-spaced so that it captures the wind and moves well. I’ve used it in great open sweeps in the Millennium Forest planting as the finale to the season there. The flowers, which are a bright lilac and finely rayed, have a gold button eye. I have a form simply named Aster turbinellus hybrid that has darker stems and dark buds that may be proving to be almost better than the straight species. I will keep them both for now and they may well be lovely planted together for the feeling that they are related yet different.

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’

Aster ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ also has a reduced leaf, although it is altogether more dense and arching in growth. It is proving a valuable contrast for the size of the flowers, which are tiny and held thousand upon thousand in arching sprays. Palest pink, this should almost be too pretty, but I have enjoyed the scale shift when it appears with the larger-flowered forms. Together they layer and billow like clouds and I’d like to see them take the garden in a storm of their own making. Come the spring, it is all too easy to forget about including these late season performers in a planting. The notes I am taking now will remind me of their importance at this time of year and will be a useful reminder when I make the divisions for inclusion in the new plantings.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage