ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

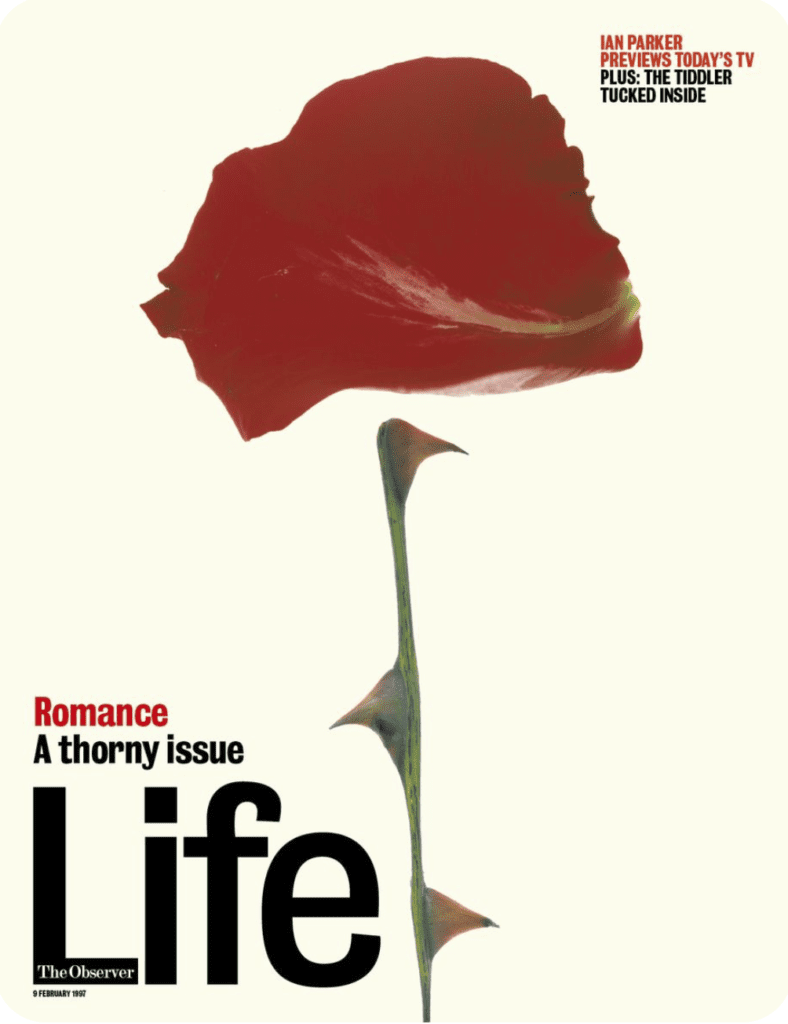

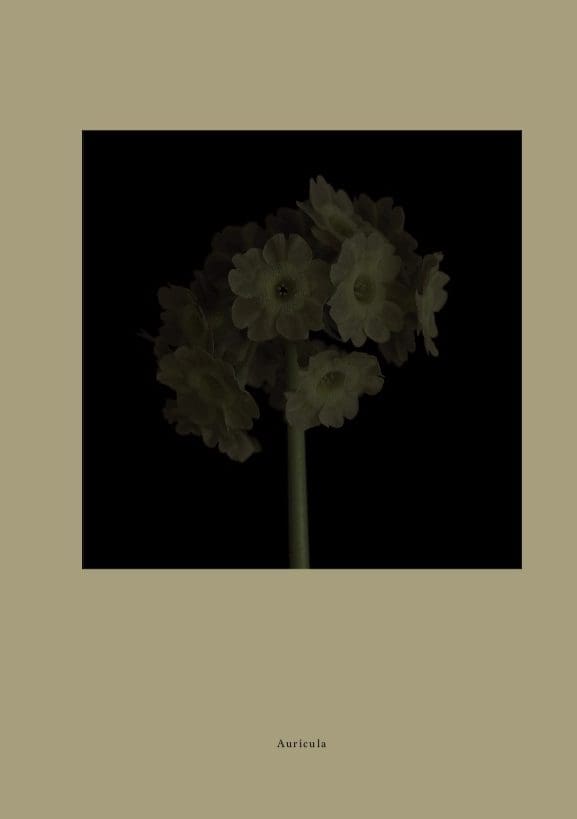

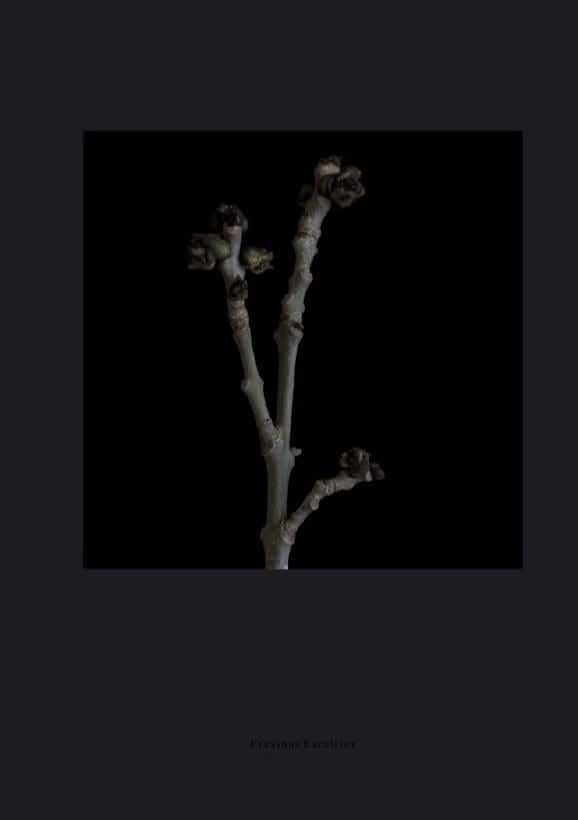

Fleur Olby first came to our attention in the 1990’s with her striking abstract plant portraits which illustrated Monty Don’s gardening column in The Observer Life Magazine. Her interest in shooting in low light prompted us to invite her to photograph the winter garden. So, early this year, and just weeks before lockdown, Fleur came to spend a day and a night at Hillside. As the clocks go back we revisit her vision of the penumbral garden.

Tell me about your interest in nature. When did it begin and were there any key experiences that shaped your relationship to the natural world and plants in particular?

During childhood I became ill with double pneumonia and had to be in an oxygen tent. My Mum brought an oak leaf into the hospital as a gift to look at something beautiful and magical from a tree close to where we lived and the thought of visiting it when I was better. I remember visiting the tree later, although now it all feels dreamlike. There was something then that I still question in the shift in perception of looking at something small in isolation to seeing it in its context of growing on a tree. The enlarged gaze of a child was full of wonder, magic and intrigue, something I have tried to recreate in my still life photography.

How did you realise you wanted to become a photographer?

During my MA in Graphic Design at Central St Martins (1992), I spent a lot of time colour printing in the darkroom, my degree show became purely photographic – Images of environmental and flower still life. My thesis explored the different ways of looking at Nature from abstraction, the single image, still life, the object in its environment, the concept of the Wilderness and a Garden and their uses within the industries of Art, Design and Photography.

I wanted to be able to work within the landscape I grew up in and the magazine aesthetics of still life. At this time, I was entranced by looking at detail, but importantly when I first started making pictures in wilderness places there is an unexplainable feeling found through the camera.

Your work for The Observer Magazine was groundbreaking at the time. Can you explain how your view of plants differed from the norm then?

I was inspired by Monty Don’s writing and both degrees were fine art graphic design – lighting and composition were always experimental. Nick Hall was my first commissioning editor at the Observer and then Jennie Ricketts. He commissioned the garden articles to be an abstraction in still life. The concept of the garden as a still life representation was different then. It was a unique time when my imagery was young and given total creative freedom. For the articles, I would regularly be at the flower market at 4 am and in the lab processing the work at midnight ready for the morning.

Although you were working commercially what made your photography stand out then was that it was clearly the vision of an artist. Can you describe you and your photography’s relationship with the worlds of art and commerce and do you still produce commercial work?

I had a good mix of editorial design and advertising and the two books were the fine art application of my work. After the 2008 financial crash and the evolution of digital capture still-life Photography commissions changed and lifestyle photography replaced a lot of the still life work. After 15 years of commissioned work, I had to change my practice as it became unviable to run a still life studio. I consolidated my archives and started to make personal work. The series are ongoing, but I would also like to work on plant collections again and garden stories.

How did your work develop after your time at The Observer ? I have read that some of the images were used in installations. Now you produce limited edition imprints alongside prints.

The Observer gardening editorial was amongst editorials I contributed to regularly for food and health and beauty. When I stopped shooting for the gardening articles in 2002 the food still life increased and I also worked for some fashion companies for still life and jewellery, perfume and interior still life.

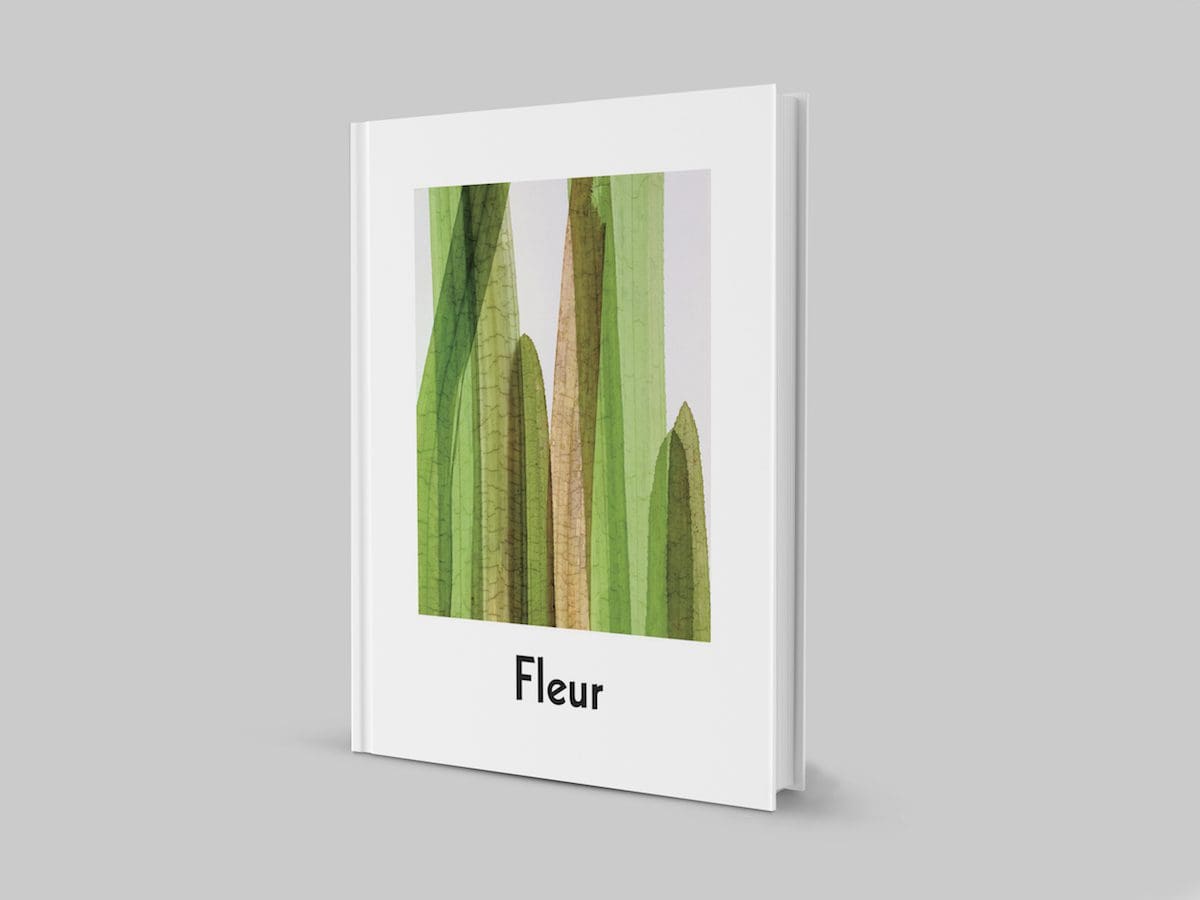

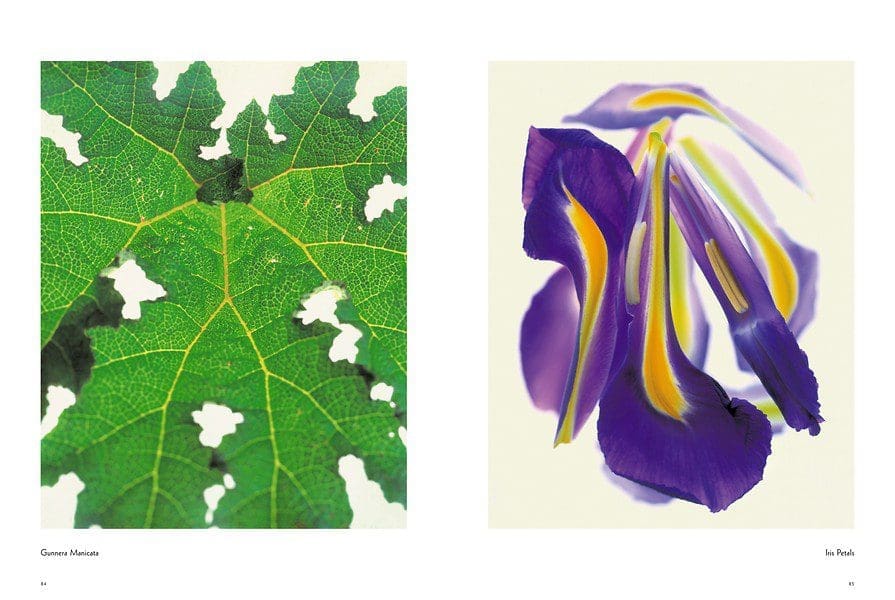

My monograph Fleur: Plant Portraits by Fleur Olby with a foreword by Wayne Ford, was published by FUEL Publishing in 2005, a combination of commissioned and personal work from ten years of floral still life. It was in the Tate Modern and The Photographers’ Gallery bookshops and distributed internationally with DAP and Thames and Hudson.

But after 2008 with two client insolvencies causing further problems after the financial crash, it took me a long time to find a way forward with my archives. The two commissions, Horsetail Equisetum for Gollifer Langston Architects and a textile collaboration with Woven Image in Australia were the archival commissions from that time that enabled me to move forward.

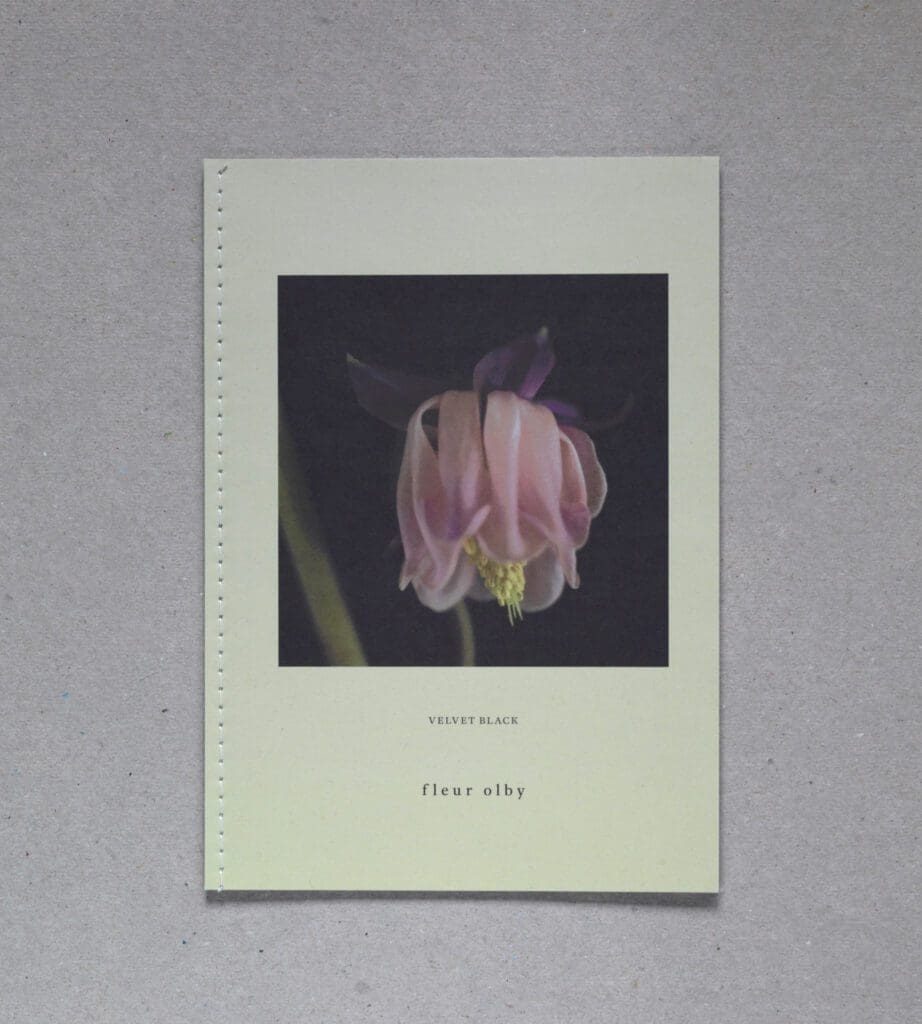

I had started a long-term project about the connection with Nature, Colour from Black. My Imprint has the first publication from these series, Velvet Black and limited edition prints that have exhibited at the Photography Gallery in the Museum of Gdansk and my solo show earlier this year at The Garden Museum, London. The A5 publication launched at Impressions Gallery Photobook Fair in Bradford and the A5 and A6 special edition are currently also at The Photographers’ Gallery bookshop in London. I aim to continue with self-publishing the series in small books and work in collaboration on the projects that evolve from them. Images from other series have also been shown in group shows in the UK and abroad.

Can you describe your process, and how your choice of film stocks, different formats and use of low light levels create the particular viewpoint you are interested in capturing?

The series artistic aim is to connect dreams and reality and through this work I have experimented with different mediums. It is less about the impact of a single image, my interest is in the pace and change of the narrative. The personal aim is to conserve plants and the elemental feeling of beauty in Nature. My commercial work was studio light, mostly shot on 5/4 Velvia and Provia film.

In my long-term series, the colour is subtle but fully saturated, in natural light. The low light started with the series Velvet Black as a present-day ode back to Victorian plant theatricals, collections and plants from a garden – the correlation between the transience of daylight and blooms.

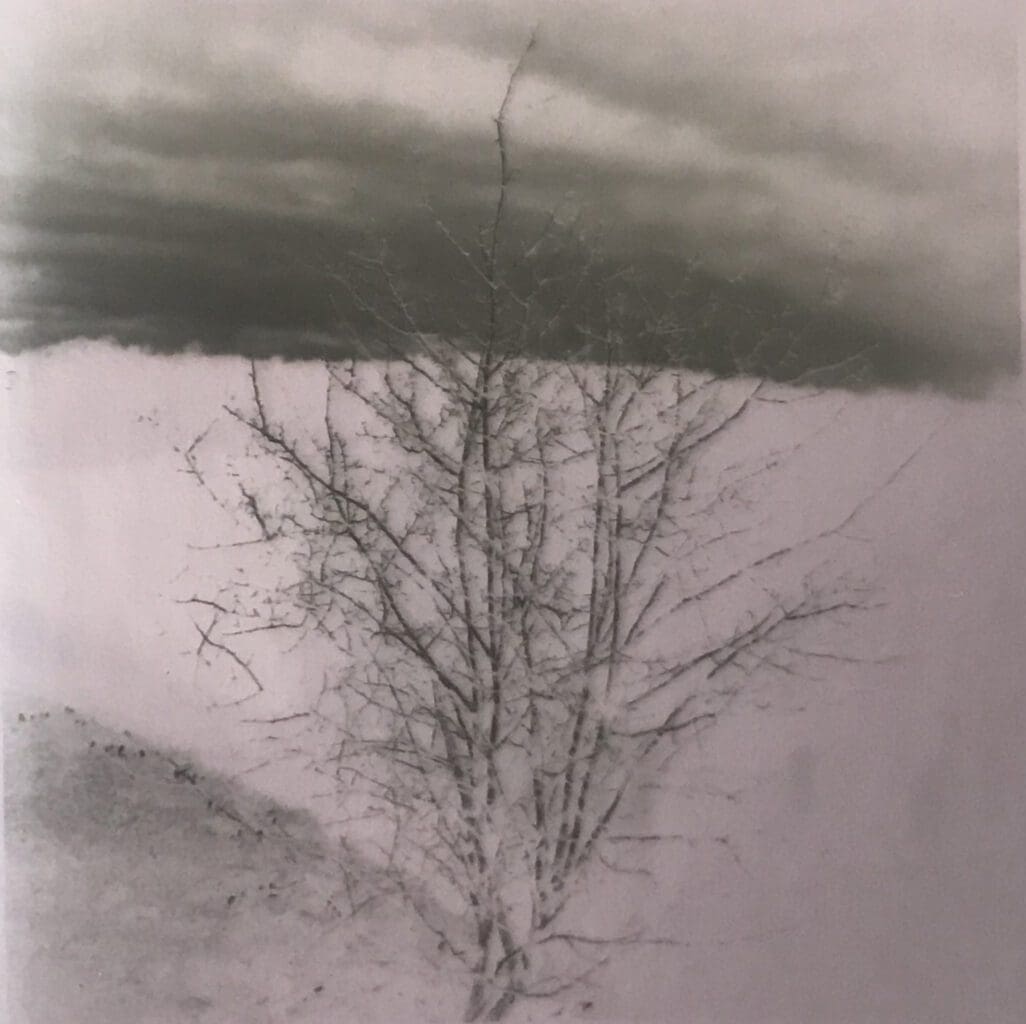

I was also experimenting with my iPhone as I was trying to capture the spontaneity of feeling from walking. My working process has evolved: It begins with walking and pictures that I revisit on medium format for a different kind of precision that allows long exposure. I am now mixing instant images and film from Black and white and colour. The series made at Hillside was the first time I combined the different mediums and shot Dusk, Dawn, Dusk in succession. I used Instax and my phone to find viewpoints from the paths. I remade some of the images on the Ipad to map out the plan.

Then I shot with a Polaroid camera in reasonable light and shot film and digital on medium format at Dusk and Dawn. The film was mostly Ilford, HP5, FP4 and XP2.

There is a quiet intensity to all of your work, a feeling of being tuned in to a different way of seeing the familiar. The fact that you work in series also gives a very strong narrative quality to your images. What would you like us to see in them?

Thank you, that means a lot to me! The quiet intensity was what I needed to reconnect with when I began to revisit childhood places that inspire me on the moors, on the hills, in the garden.

With the narratives about Nature, I wanted to slow down the viewing process and to question the feeling of Beauty through light and repetition within the series. In the book Velvet Black I use the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper and the folded pages to slow down the process in a similar way to a flower press. And the printed absorptance of the page makes the transient process of nature into a permanent object.

There is a distinct balance in your work between wild, elemental landscape and the intimacy and perfection of a single cut flower. What is the relationship between these two worlds for you?

I think this is the path I am trying to narrate between the perfect oak leaf from my childhood to the tree out on the hills.

When we asked you to come and take photographs at Hillside what were your first thoughts ? When you were here were there any particular observations you made about photographing a garden set in landscape?

It was great to hear from you both. I was excited about the thought of visiting Hillside. I remember our conversations about the work you were inviting artists to make and what aspects of the garden they were focusing on. But on arriving I couldn’t think how to divide it up into one particular interest and I knew I wanted to convey feeling.

I arrived between the storms of February, the quiet calm lull in the garden was breathtakingly beautiful. No-one was there until later today.

I started to walk – the paths led me everywhere. Enclosed and defined by the garden in and out of the landscape. I did not know this terrain, the feeling and scale are different, the quiet remains the same – the shape of the hill on the left is gentle and round, it stretches out into another at the front with incredible mature trees. The main garden is perched high up within the undulation of the hills. How will I capture this?

I felt I was intruding the serenity of the place, I stood amongst the plants’ skeletons taller than me and thanked them for remaining standing despite the storm – looked out at the echo of the trees beyond, walked down the hill towards them and looked back up to where I’d been standing – It is like a painting, brushstrokes of layered texture highlighted by the time of the year and the trees and hedges beyond it, darker shapes in repetition above. Light in colour as its ready to be cut for new planting and the two gates take me in and out of place and garden and into wonderment. I’m not sure I can express this.

Then there’s the bridge at the bottom of the stream with wrapped up plants on the edge that I could spend all day shooting, the vegetable garden! The artichokes! The Cavolo Nero – The two architectural stone troughs define the scale of the outdoor space and feel spiritual, a verbascum ode nearby reminds me of my Dad and makes me smile, the hedges, the orchards and the young woodland at the back. Flowers resiliently here and there touched me – intricate planting inspired me. I had to process a plan and start.

I wanted to try and capture this movement, the feelings from walking this dreamworld and its reality. I worked on different cameras in repetition in positive and negative to intensify the shapes and colour and black and white to intensify the feeling and pictorially play with resonance.

Do you feel that you learnt anything new from the time you spent photographing here?

It was immensely helpful to be invited to work like this, and I enjoyed the intensity of making the work. I made a new working process shooting 3 formats and running between captures to put the instant film to process inside and continue with the film outside. I made quite a lot of work in the time and it was the first time I shot constantly connecting dusk and dawn.

It enabled me to see how my work has progressed more clearly and how I can put it together because it was the perfect balance of how the garden and landscape coexist.

How was lockdown for you creatively?

Lockdown happened during my show at The Garden Museum.

I contributed to Quarantine Herbarium’s cyanotype project and the Trace Charity Print Sale which raised money for the charities Crisis and Refuge.

I listened more to the birds, watched the animals’ paths and felt exceptionally close to them and that continues. I was also busy shielding family, and I spent more time growing vegetables which I do as much as possible.

I stopped shooting and started to edit more.

What are you working on now and can you share any ideas you have for future projects?

I have had to revise my plans for this year, events I had committed to were cancelled. I am reworking everything and plan to bring the next series out in 2021.

The full edit of the photographs Fleur took can be seen on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Portrait: Howard Sooley

All other photographs: Fleur Olby

Published 24 October 2020

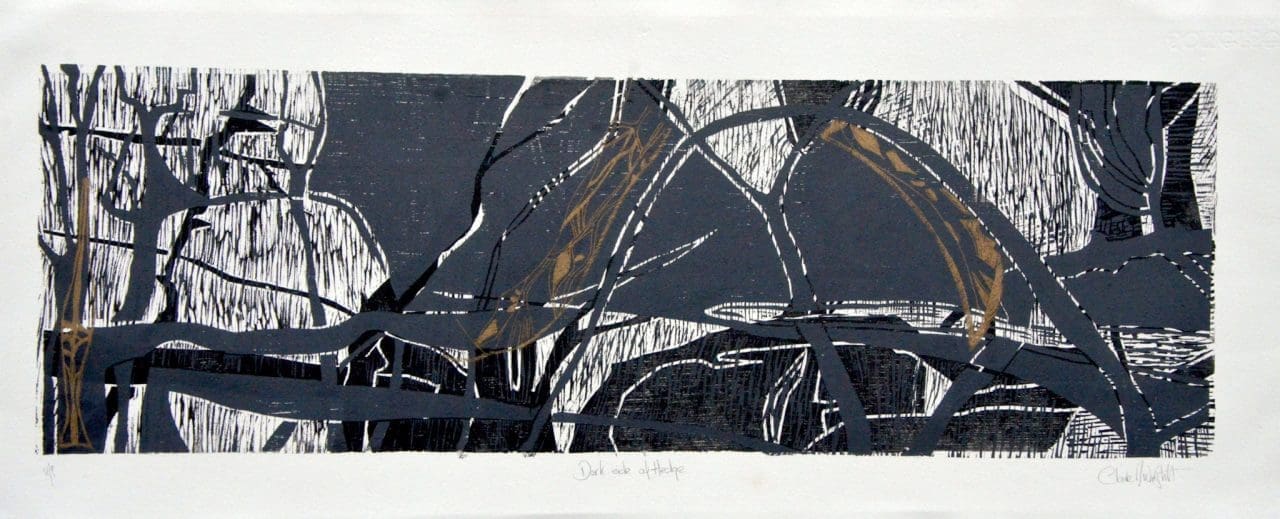

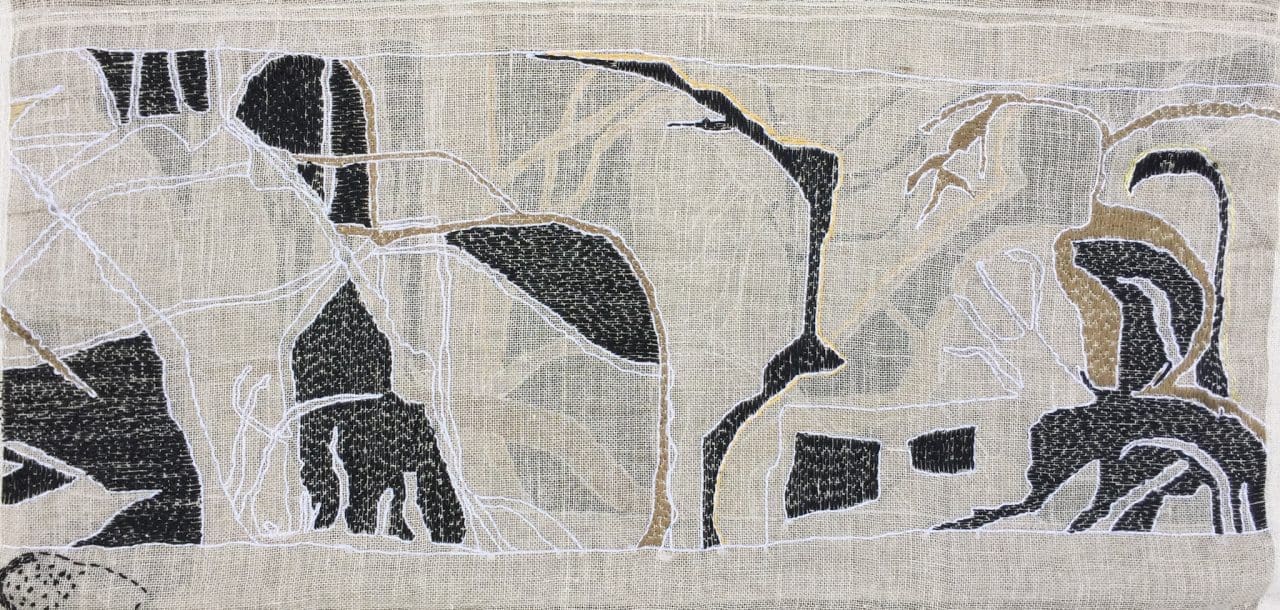

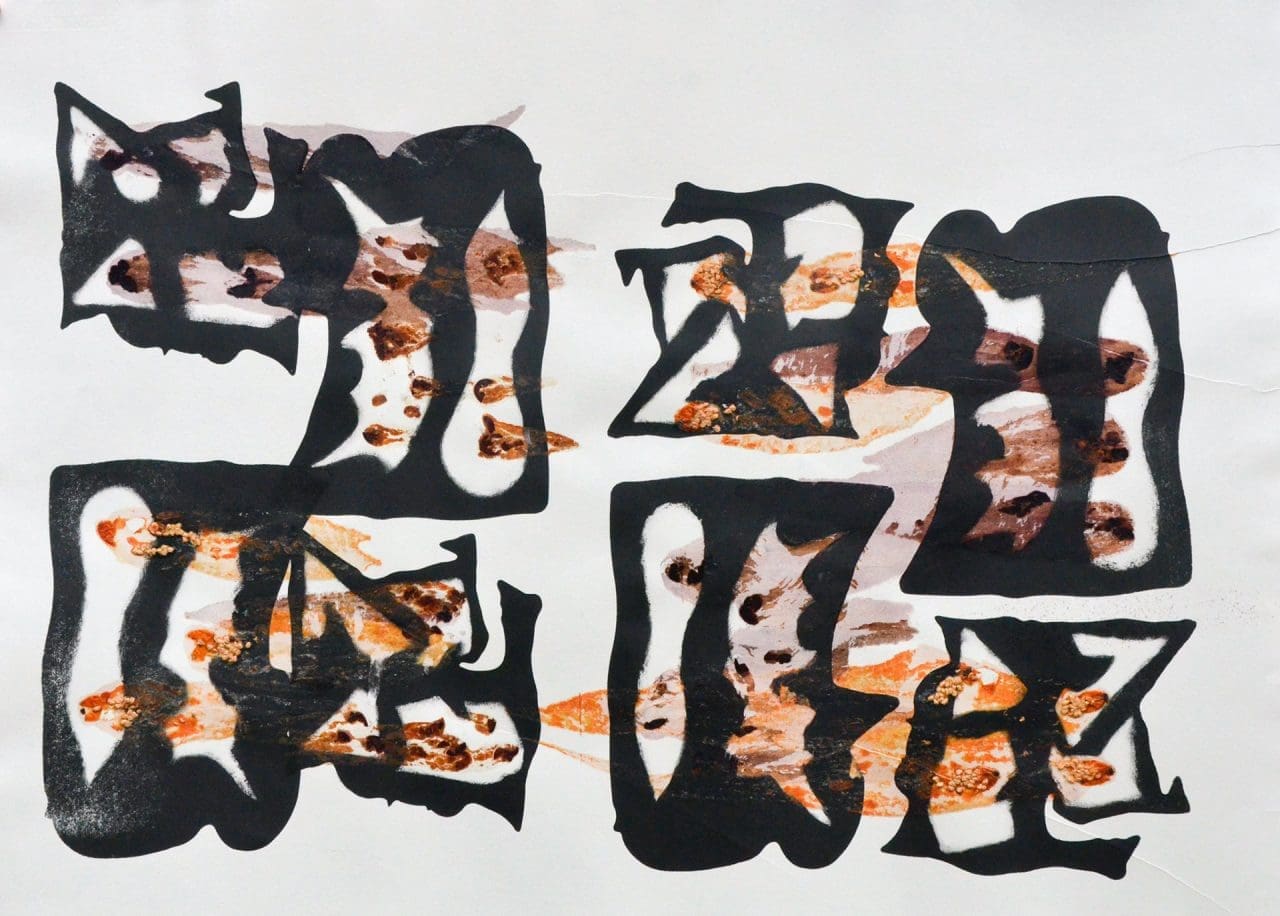

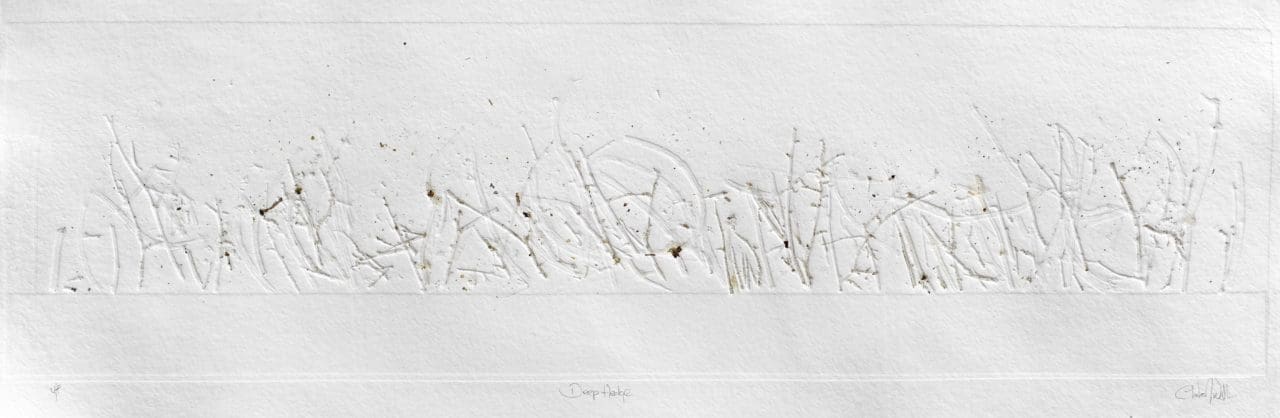

Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

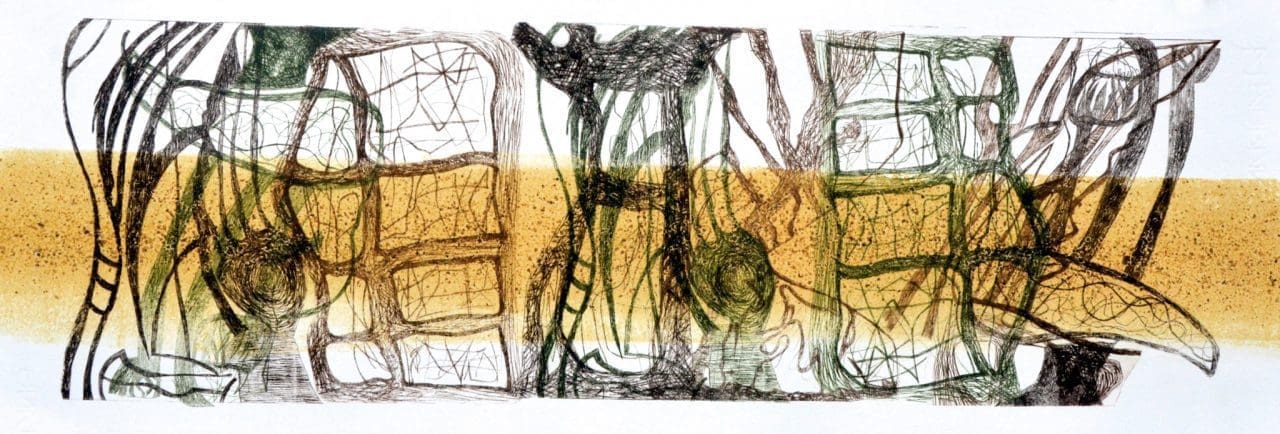

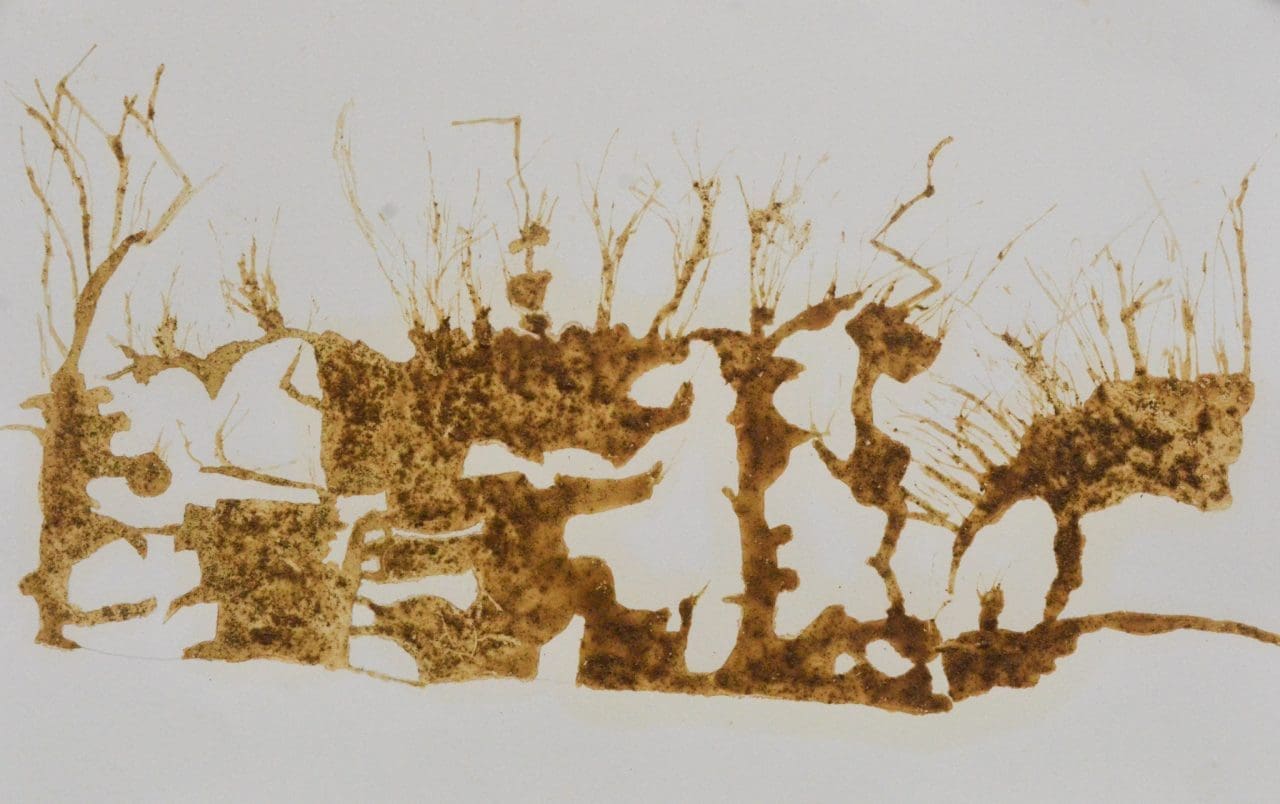

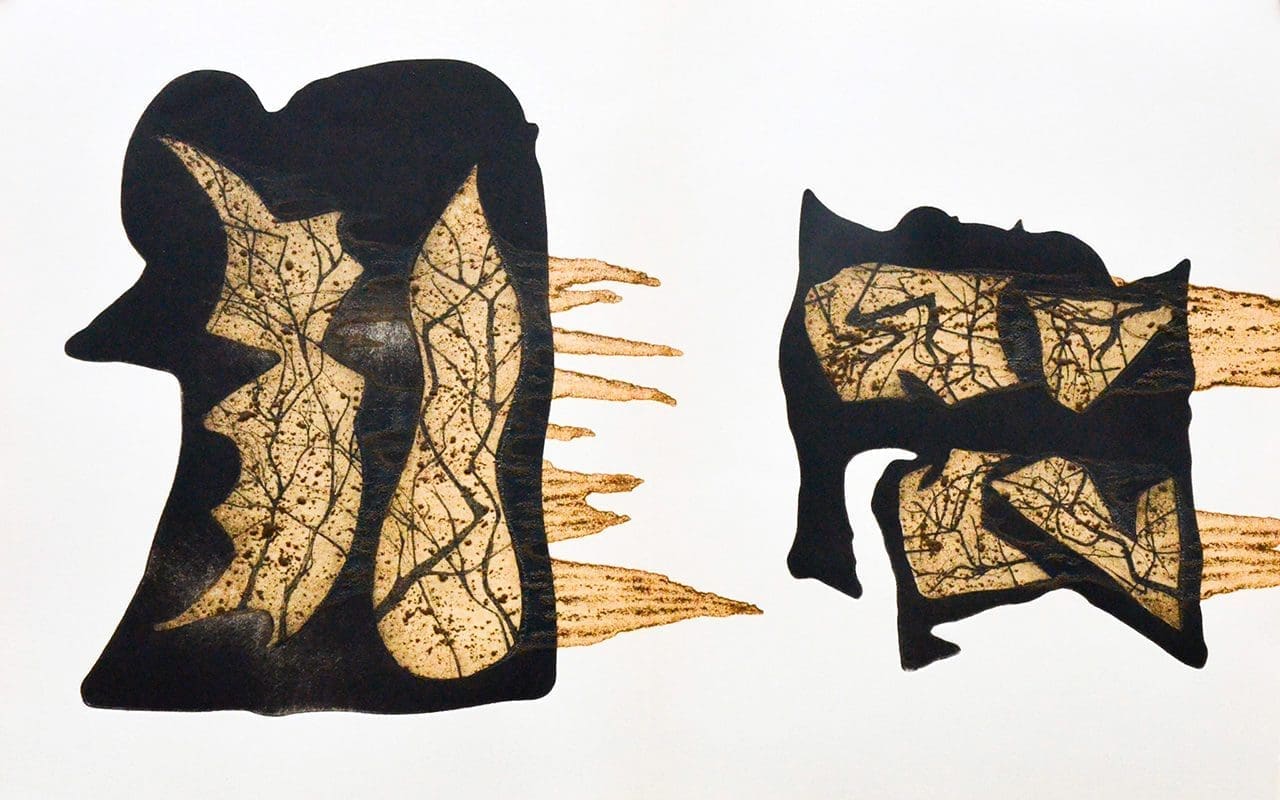

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

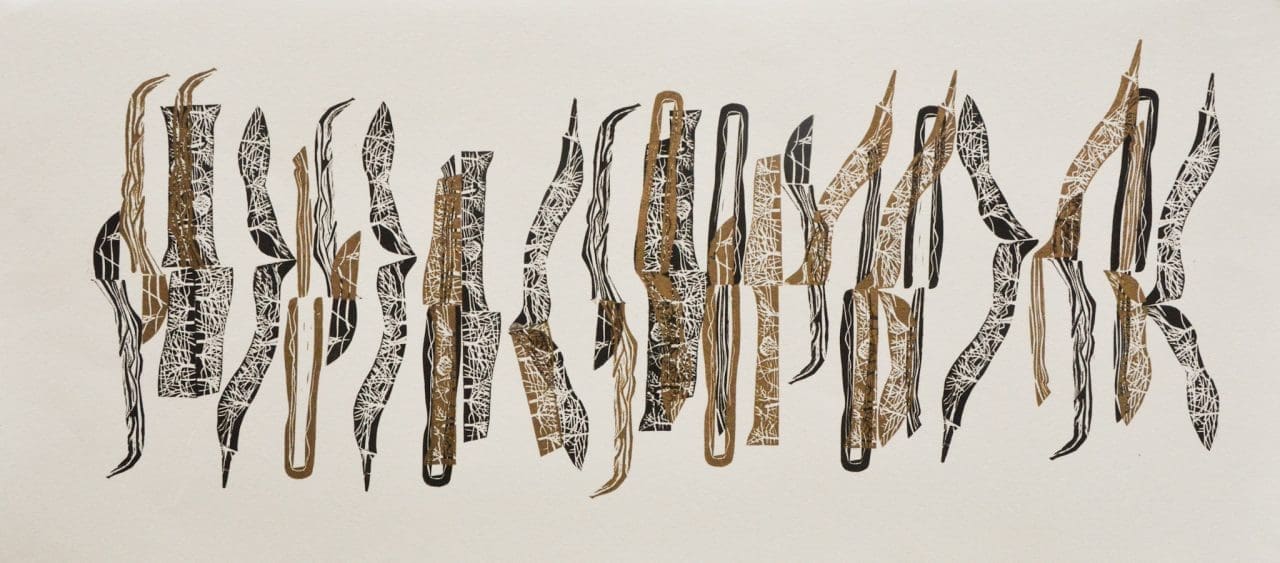

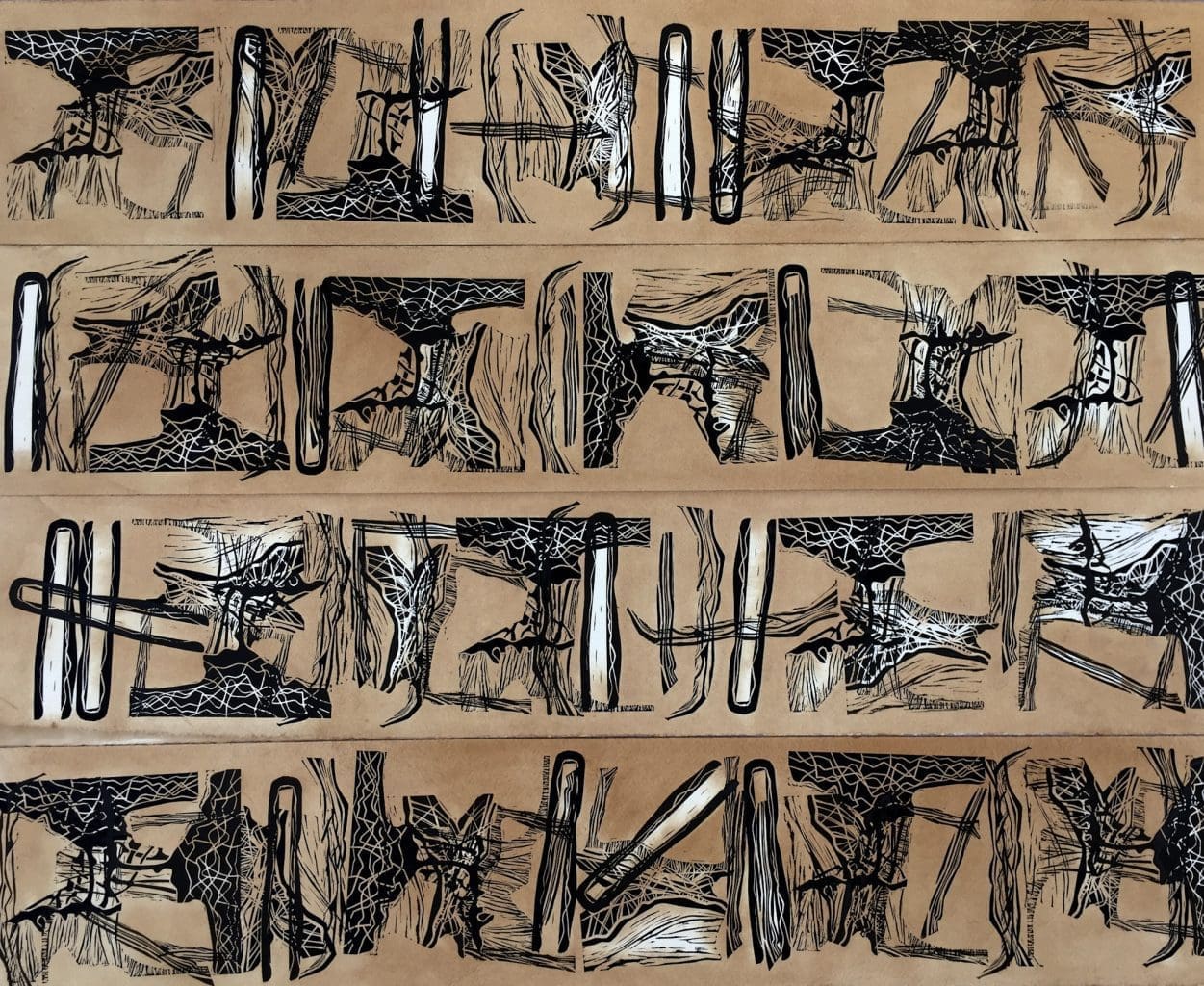

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

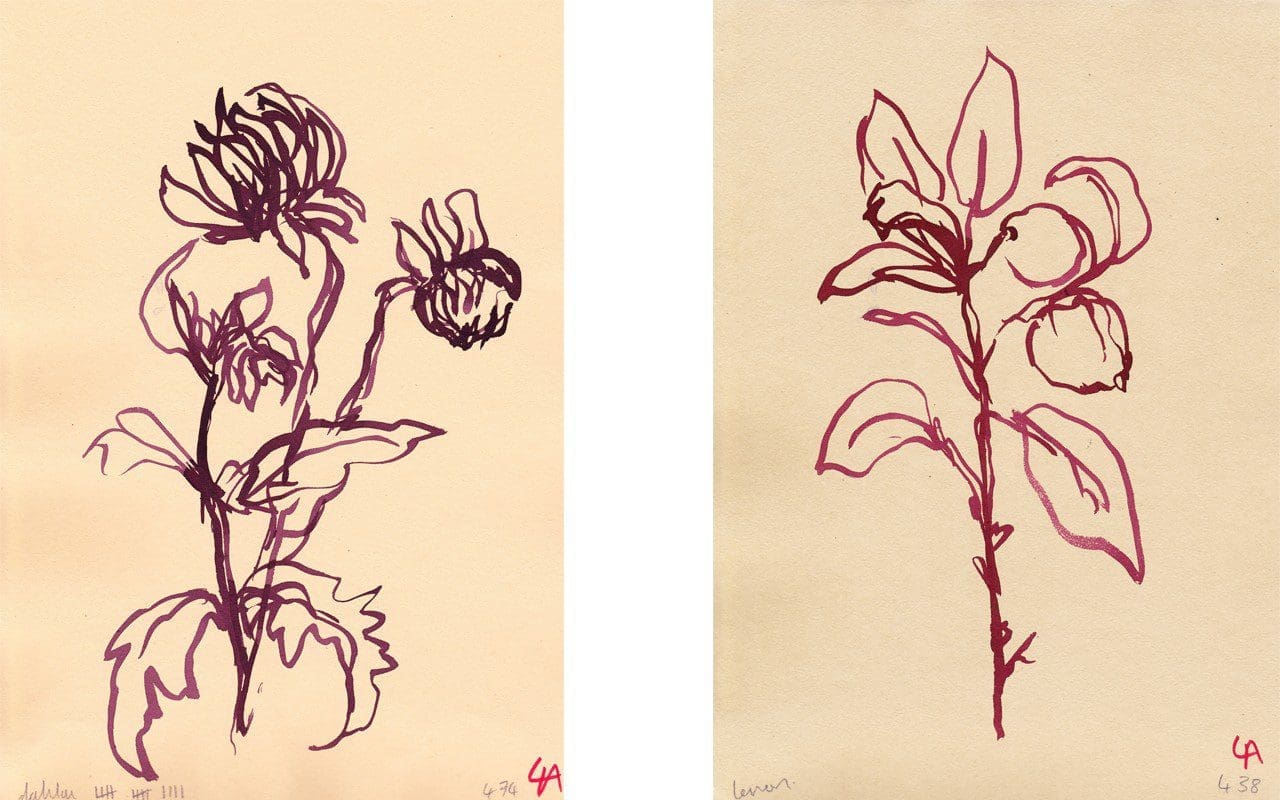

Lucy Augé is a Bath-based artist who has an passionate interest in the variety of flower and plant forms which she paints with Japanese inks on a wide range of specialist and vintage papers. Her intention is to capture the ephemeral and fleeting moment. We met last year and, after introducing her to the Garden Museum, she showed some of her new tree shadow paintings there earlier this summer. Since June, Lucy has been coming to the garden at Hillside to capture a range of the plants here on paper.

How did you come to be an artist ?

I always wanted to be an artist, even from being a child. For my tenth birthday I didn’t want a party, but wanted to go to Tate Modern, as it had just opened. I think my mum thought, ‘Oh God. Choose another career path !’. I had always been creative at school, I was never really academic, so I got funnelled down a channel into being ‘artistic’. That then followed me through to college, but I thought I couldn’t be an artist, so I did graphics, and thought I’d go into magazine design, as I had a passion for French Vogue at the time as it was so well art directed.

Then I had a really bad brain injury from a fall, and that left me very, very ill, at home. I couldn’t go back to university. I couldn’t do much, as I was having four seizures a day, and thought, ‘OK, life’s over’, but then I started gardening with my father, and that’s where I started noticing – I was going at such a slow pace, because I was so ill, I’d have to be carried down to the garden – and I started noticing things more, because I didn’t have any distractions. I didn’t have a phone for two years. Not that I was cutting myself off, I just didn’t need it. So I just started looking at nature all the time, and then I just started painting it. Repetitively. Or I was watching gardening programmes on repeat, because I wanted to know more, all the time. So, that’s where, through the illness, I got the passion for gardening and my painting.

When I finally went back to university I just felt it was very redundant for me. I went back to the graphics course as I was already a year in and because I don’t really like to give up, but I knew the tutors didn’t really like my work. They were looking for a very graphic, computer-generated style of work, and I then generally only worked in felt tip, keeping it hand drawn, but still trying to fit in with the current look that was around at the time.

So what happened after university ?

I got picked up for projects while still at university and, when I graduated, I did packaging design and worked with Hallmark, but I quickly knew I wasn’t an illustrator, as I can’t draw just anything and my passion lay with nature and studying that, rather than drawing a family of badgers eating cake. No joke, that was an actual commission.

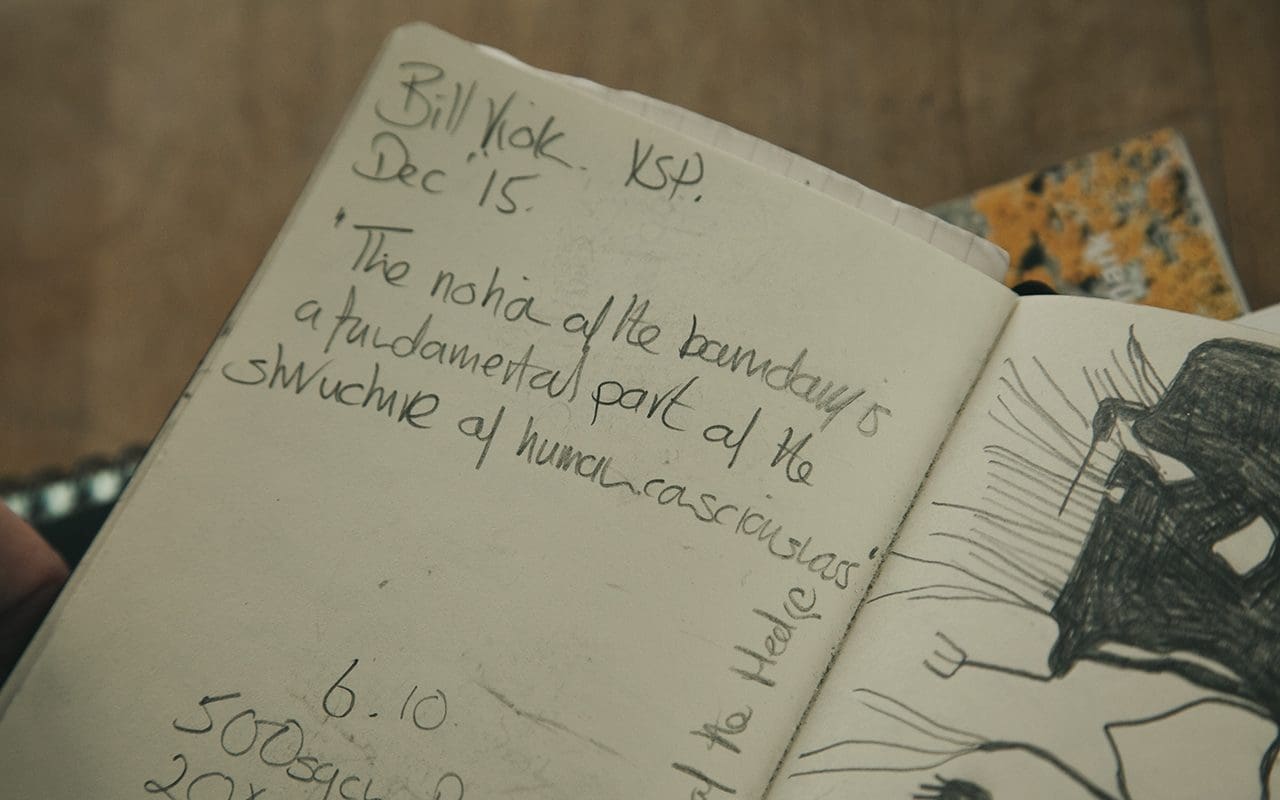

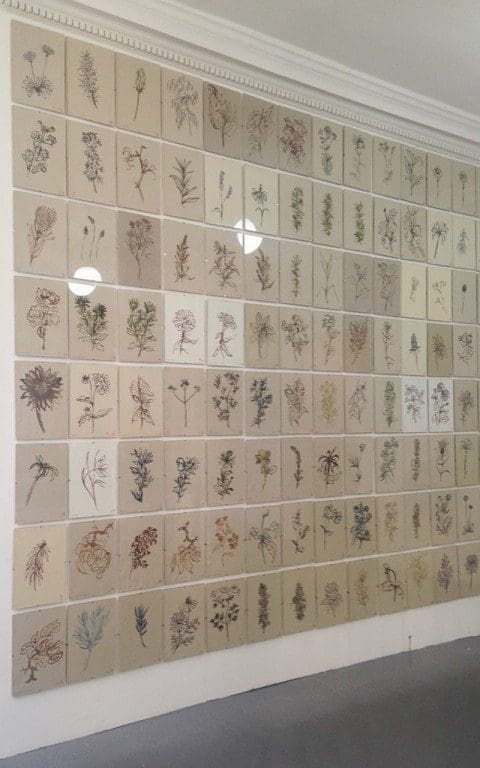

The 500 Flowers exhibition came about after a month I spent in LA in 2015, where I had a meeting with the art director at Apple of the time, who had offered to mentor me. He set up a meeting with a carpet designer who I was supposed to do collaboration with. However, when he met me he told me that I wouldn’t be an artist unless I married someone rich, and that he would only work with me if I got someone to buy one of his rugs.

I was enraged by this and thought I was tired of waiting for someone else to launch my career for me. So I came home determined to make an impression alone, booked a rental gallery space in Bath and put on my first show on my own. The idea originally was to paint a thousand flowers, but that was near impossible in the time frame I had set myself. My brother calculated I would have to complete one every ten minutes ! So I painted five hundred, with the aim of painting every species that I came into contact with.

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

The exterior and interior of Lucy’s rural studio in Somerset

You produced all of that work and organised the exhibition yourself. What was that experience like ?

Well, I had five hundred A4, individually painted ink drawings, which I had completed in three months, and that both evolved my style and I became very confident at drawing. I also priced them at £40 each, which I think some people thought was madness, but at the same time nobody knows you, you have no reputation, and so £40 can seem like a lot for someone, but it was great because it made it affordable so that people would buy maybe nine or twelve at a time. An interior designer, Susie Atkinson, bought sixty. And so it got my name out there, because I was affordable.

The exhibition took place in Bath and I made sure I had beautiful letter-pressed invites. I invited everyone I’d ever met, contacts I’d made on Instagram or through business or who had shown an interest in my work. I invited people who I really admired for their work, which is why you and Dan got an invite. I just wanted to show people that this is what I do, this is my passion and if I fall flat on my face and no one comes and nothing sells, at least I would have known that I’d given it 100%. And then I’d have gone and got another job !

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

Installation view of 5oo Flowers

But it worked out in my favour. I had a queue out the door on the first night. I sold over eighty in the first couple of days. Then House & Garden emailed me to ask if they could have nine for their show, which the editor ended up buying. The assistant editor then bought another nine, and she put them up on her Instagram and I ended up selling out in five months. That then led to shows in Japan, San Francisco and elsewhere. It confirmed to me that, yes, you are on the right path, you’re doing the right thing, and the proceeds of that first exhibition went towards buying my studio. Before then I was working in a barn with no windows, no natural light, no loo, and so that exhibition was my make or break. Otherwise you can be creating, and calling yourself an artist and saying ‘This is what I do for a living.’ and yet you’ve never really put yourself out there, and so I thought, ‘baptism of fire’.

Then I started getting commissions from people to go and draw on their land, their flowers, which was really great. The best of those was for Gleneagles, which was the highlight of my career. I was flown up to Scotland, where I’d never been, and stayed at the Gleneagles, which was an amazing experience, and I went round the estate and drew all of the plants that were there at that time, and they are now hanging in the American Bar. And it was just so nice to know that people understood what you do.

Were you starting to charge a bit more for them now ?

Yes, I did raise my prices. Although I didn’t charge a lot because I wanted people to have the chance to invest in my work. I come from…my father grew up with no money, but he was always passionate about art, and just wanted someone from his background to be able to go, ‘I’m going to invest in something. Something beautiful.’ So that they can own real artwork. And I think that is a real gift to be able to do that. Especially as I had five hundred ! And the consequence now is that they have travelled all over the world. I love that there are some in Singapore, and some in Brazil and I don’t think I would have got that kind of international reach if I had not priced them so competitively. Of course, now my prices have gone up and I don’t need to produce as many. My last catalogue only had twelve paintings in.

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

Six of the paintings from 500 Flowers

What was the medium you used for the 500 Flowers paintings ?

Ink. On antique paper.

I’ve seen some of your work which is very highly coloured and looks like it is done in felt tip ?

Yes, that’s right. That’s when I was still trying to be an illustrator. With those I was trying to fit in with the norm, so everything was very highly coloured for editorial. I would say that that was the only time I have ever tried to fit in. It worked for the clients to a point, but I kept being told, ‘Your work looks too much like you. There’s something to it, but it’s not commercial enough.’. So I gave it a year, doing that kind of work and I just grew out of it very quickly, because it wasn’t me.

There appears to be a strong Japanese influence in your work.

I love Japanese and Chinese art. I’ve always loved Japanese and Asian culture, so it’s always been in the background. Anything from there I could get my hands on I wanted to have a look at it, absorb it. Then I saw a show of Chinese paintings at the V & A, where I learnt that they were painting with natural pigments, so with copper and iron and earth and plants, and it just made this wonderful colour palette. So I found some Japanese inks that have that same antique colour palette, and it just felt much more me. It’s hard to put my finger on it, but it just started to fit better with the kind of images I wanted to make. And with the paper. I had never wanted to work on white. I had this antique paper, which had been in my godmother’s attic, which had the same feeling as the old Chinese papers I had seen, because they are made entirely from natural elements. So my choices were about aspiring to that antique colour palette. The other thing that struck me about that exhibition was that the artist was always invisible. The painting was never about the artist, it was about nature, landscape, weather, the seasons. It was about the everyday. And I thought, ‘Yes. Art can be like this.’ Because as I was growing up when everything was about high concept or shock, shock, shock or politics. The stranger the better. How far can you push it? And looking back at older art – one of my favourite artists is Monet – was deeply unfashionable and seen as suspect. But I love how he could just paint waterlilies and the resulting painting becomes this charged, emotional landscape.

Is that one of the reasons that you didn’t feel you could really be an artist ?

Yes, completely, and it’s one of the reasons I considered commercial art to begin with. Also I was never really encouraged at school, bar one teacher, to pursue my art. You were told that you needed to fit in. And I think as an artist you do need some kind of validation that what you are doing has value and that this is what you are supposed to be doing. And I never really got that until I put myself out there and had people say, ‘We want what you make.’ Because otherwise you can be drawing for just you – and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that – but you do have to decide that you are going to be an artist, and I made that decision after the success of that first exhibition.

I could have gone in one of two directions. I could have just put my flowers on anything and gone down the commercial route, or choose to refine the work and make it more considered. I have had a few commercial collaborations, but I have been very choosy about who I have agreed to work with or who I have approached. And I then reined it in and have now moved my work away from it, as people lost the meaning behind what I was trying to do. So they just wanted a picture of a lily as their daughter was called Lily, which is fine, but it missed the ethos of the work.

Which is ?

Seasonal observation through nature and plants. Forgotten moments. The immediacy of right now. I always found it interesting that the first pictures to sell out always are the ones of weeds. Those are the ones that people really want. I think because, as soon as you paint them, and strip everything away, you can see the beauty in them, and the fact that they are so mundane, but the painting elevates them. Honours them.

Do you know that there are 56 seasons in Japanese culture that relate to the flowering times of 56 different plants ?

No, I didn’t. How fascinating. I can so relate to that. I get quite anxious at the possibility of missing things. You know, like cow parsley. I’ll have a great idea, and then two weeks later I’ll have the time to get onto it, and all the cow parsley is gone ! So now I prep my paper in advance and cut it to the size that I want so that, when that moment presents itself, I can just say, ‘Here I come !’. That’s why when I came to your garden I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s definitely going to be, sorry to say for you, a much longer process than I had envisaged, as I now would really like to be there in different seasons.

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

Installation views of the exhibition at the Garden Museum

What does your work mean for you personally ?

Very generally it just gives me that quiet time. You don’t have to think about anything else. Once you get into a process – it’s a bit like gardening in a sense – it gives you that same mindfulness combined with productivity, which makes me feel at peace. You’re just drawing, or gardening, and that’s all you’re thinking about. And then sometimes you’re not even thinking at all, but are completely lost in the process of activity. That’s what I really love about what I do. It’s quite addictive. It empties your mind and is very meditative. I’m a worrier. I do worry too much and it’s quite nice to be able to say, ‘I’m not going to think about anything now.’ And I’ve always been quite confident in my own work, so it feels like a very safe space when I’m creating. And once I’m happy with it and happy to put it out in the world, it’s done and I can move on.

Until then – and that’s why I have my studio away, remote. I don’t want to hear everyone else’s opinions – I don’t actually show anyone my work until it’s at a certain stage, which is almost finished. It gives me a degree of freedom and escapism. Which is why it didn’t work for me as an illustrator, because someone else is dictating what you’re going to draw, your process is held ransom by deadlines, and I’ve never been any good at being told what to do. Ever. I will question and question to understand why I should do something. Just because I’m curious, but having it be just my own work I can ask my own questions and be curious about where it’s going to go next, how am I going to paint it. And I know what I am looking for, rather than what somebody else is looking for and wants me to produce. I do find it difficult when someone says, ‘I have a tree in my garden. Can you paint it ?’, because the tree might not be the thing in their garden that I would want to paint.

What are you looking for ?

In paintings I think it’s a stillness. I really want to portray stillness, or a captured moment. So everything has to be painted from life, because it feels fake otherwise. Sometimes I do draw from photos, but you’re just not capturing that moment when that leaf on that plant might have been at an awkward angle. You might not have seen that from a photo, so that’s really interesting to explore.

The 500 Flowers were all painted from life. Firstly, all near to me and around the studio, so a lot of wildflowers, but also some bought flowers, and that’s how I got in touch with Polly from Bayntun Flowers, because I looked up ‘local cut flowers’ online and saw what she was doing and I thought, ‘Brilliant !’. She had amazing heritage varieties and luckily, when I asked her if I could visit to paint, she said, ‘Yes. Come on round!’. I was like a child in a sweet shop. The first day was so exciting I must have made about forty paintings in one go. I would normally paint about five or ten. But the garden there was just chockablock with species, lots of which I hadn’t seen before, so it was very exciting and it got me up to five hundred !

But then it was hard when the winter came. I wasn’t aware of how much I would suffer. I became quite, ‘unusual’ in the winter, because I panicked and thought, ‘What am I going to draw ? Everything’s over. My work’s not good enough.’ It was really tricky. You’ve been doing all this painting and you’ve got this absolute high from painting all these things, because there are endless possibilities and inspiration in the summer, and then my first winter I didn’t know what to do. I was really looking and trying to paint winter, but really everything is just dormant and that’s when I realised I have to know what I’m going to do when winter comes. Not hibernate.

So now in the winter I paint a lot of dried leaves and stuff like that. The first winter I was so busy, doing commissions and collaborations, that I didn’t really notice. It wasn’t until winter 2016, a year after the show, that it was total panic. A flower desert. I thought maybe it was time to do some abstract stuff, get back into illustration. It was bleak. And then there was stuff going on in my personal life, and what’s going on in my personal life does feed into the work. If I’m having a grumpy day I will most likely pick out a mopy looking plant. It’s weird. I didn’t even realise it till someone else came to my studio and said, ‘This is all a bit melancholy.’ It’s frees such an subconscious part of your brain when you’re drawing, you’re not really thinking, you’re just observing. When I saw how my moods were feeding into my work I wanted to explore that more.

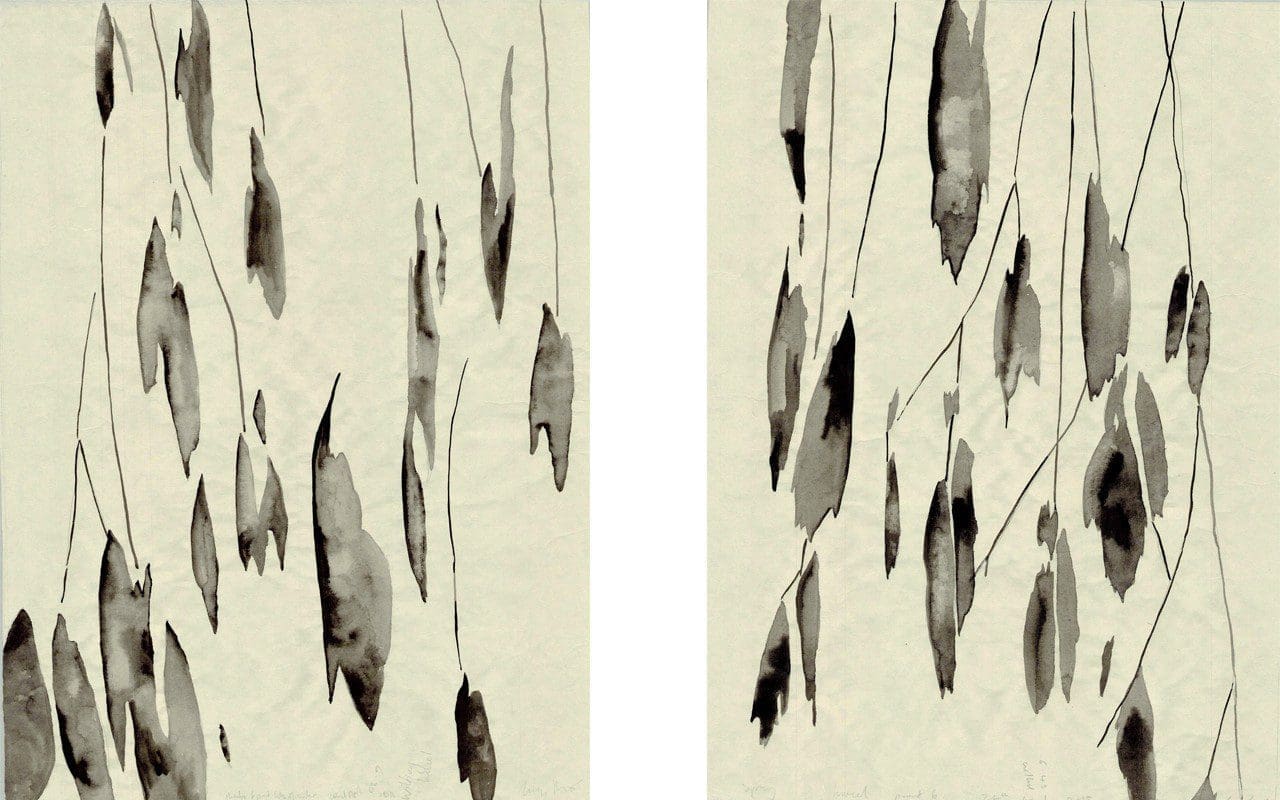

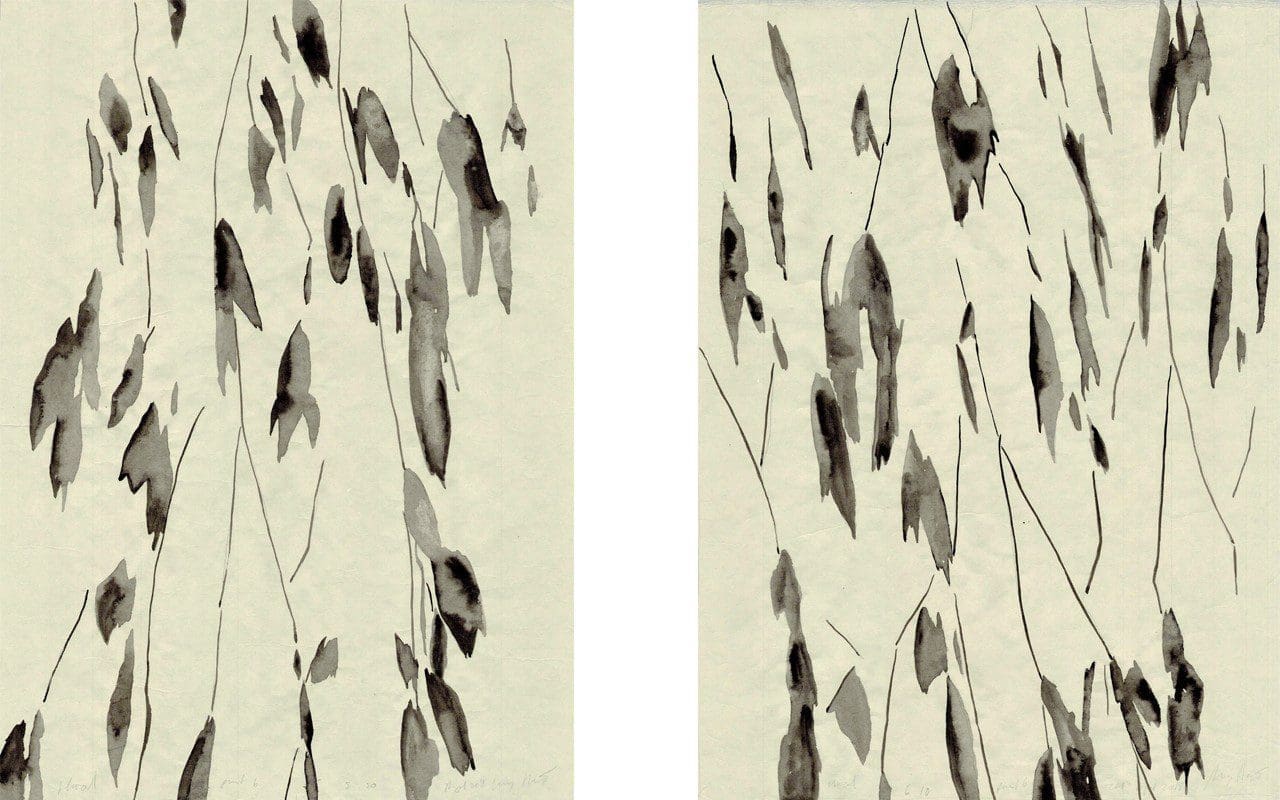

The paintings that I relate to the most, like Monet’s waterlily triptych, that he painted as a reaction to the war, is so powerful and emotive, and it is ‘just’ waterlilies, and I thought I would like to try and harness that emotional connection more and be more aware of it when I am working. So the tree shadows that I have been doing most recently came about because I had drawn so many flowers – I mean I was well over a thousand different flowers by now – and I was starting to fall out of love with them, even though there were commissions paying my bills. I thought, ‘I’m on the way to making myself into a performing monkey.’. I was getting set flower lists from people, with direction on paper and ink colours and I thought, ‘I didn’t start doing this to make ready-to-go flowers.’. It wasn’t me, and felt like I was heading back into illustration territory, which I had dragged myself out of.

But then it all changed because the farmer that owned the land that the barn I was renting died and so my studio tenancy went with him. I also had some financial worries. I didn’t want to paint another flower even though it was full on summer time and I was just lying in my studio taking a nap and I could see the reflections of the trees in the glass of one of my old pictures. And I thought it was interesting. I had also been experimenting with totally abstract ink paintings, which I would cut up and make into smaller single frames. But that didn’t fit in with anything that I was doing. But I started to think about how I could bring these things together. I started trying to draw the outline of the leaves onto the frame, but that didn’t look right. Then I started drawing outdoors, which I had always done. All five hundred flowers were drawn outside. But I couldn’t get a high enough outline definition.

That’s when I realised that everything moves so quickly. I would go and get my water bottle from the studio and, by the time I got back, the shadows had moved and the picture was different. That’s when I also started noticing the weather. Timing was everything. Before that I had just been aware of when each flower I was painting bloomed – this in when the roses are here, this is when the daisies look best – but not the bigger picture. When I was drawing the flowers I was more aware of the different varieties, because when you watch gardening programmes and learn that this is what a rose looks like, this is what an angelica looks like, and then when I would go out into the fields I would think, ‘Well, that has the same leaves as a rose. That looks like an angelica.’ And so then I was learning, without any books or anything, about those wild plants. Even though I didn’t know the name I was able to match them up.

What I was finding when I started doing the tree shadows was that , even when the shadows distort, they each have a particular look. Aa certain space between the leaves. The reason I like painting hazel is they have a lot of space between the leaves. I’ve tried painting quite a few different trees, but have found what works and what doesn’t work for me, for my aesthetic. I’ve also learned that, at four o’clock, you won’t be able to get hold of me, because the phone goes off, because that is the time I’ll be painting the shadows. That’s one of the things I noticed at your place. It wasn’t four o’clock. It was later. More like five thirty, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference, because that’s when you’ve got the high definition of the shadows, like on the irises that I tried doing. And where your site is so exposed the light seemed to move so quickly. I only had a half hour window, and that was it. Whereas where I am I can start at four and not finish until seven. The angle of the image changes, but at yours I was surprised at how the time made such a big impact. It’s taken months to understand that. When is the right time to draw. What is the best weather.

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

Four of the series of paintings of hazel shadows exhibited at the Garden Museum

When did you start doing the tree shadows paintings ?

August last year. It was purely by accident. I had some leftover scroll paper and I had this birch branch and was trying to paint up into the canopy inside the studio. So I’d hung it up and then I saw that when the sun came in through the window, there it was on the ground. So I thought, ‘Oh, quick ! Get it down. Start drawing.’ I wouldn’t say that I’m drawing the outline, but more what I saw, because things move so quickly that you can’t get the exact outline, so there is a bit of interpretation involved, but I still want to be quite true to what it is, and if what it is turns out to be an awkward picture, I quite like that uncomfortableness.

So that first shadow painting, and I know this sounds cheesy, made me feel re-awoken again. I thought, ‘OK. Let’s restart.’ It was a risk, giving up on my flower paintings, which was bringing me in income, and then you think of going to your audience, who know you for your flowers, and saying, ‘I’m doing tree shadows now.’ But, the response was really, really positive. And it has been encouraging to hear people say, ‘You know I really liked your flower paintings, but I lovethe tree shadows.’

I think it’s because they feel more like art to people, whereas the flower paintings were more illustrative, the tree shadows are more abstract. But I think that doing the 500 Flowers gave me some validation, which means it is easier for people to feel comfortable with the change in direction.

When I was trying to capture a landscape through paintings of individual flowers – this is what grows here, this what I have seen and recorded – when I was in Scotland the flora there was very different, and it created en masse a very different painting. Different shapes and texture. Quite thistly, spiky plants, due to the hardier conditions up there. But not everyone got that, whereas everyone seems to get the tree shadows. I’m just really enjoying exploring it and see where it goes next.

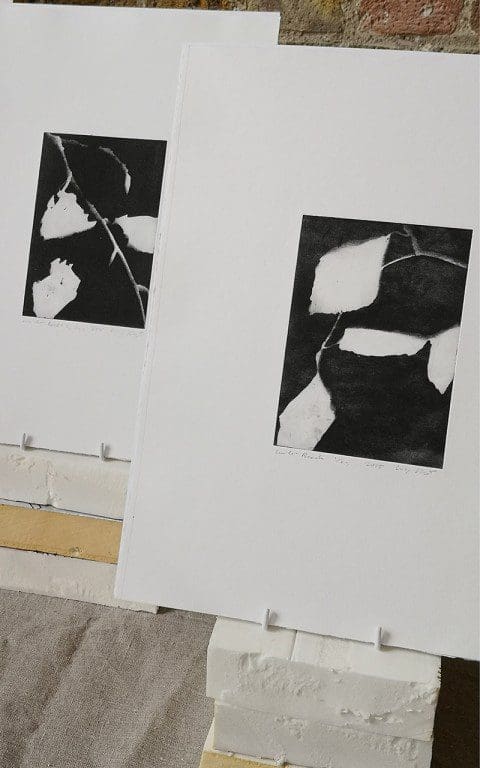

I tried for two months earlier this year trying to capture the light coming through the canopy and it just didn’t work. Everything is a result of where I am working. My studio was too hot to work in, and so I was working under a tree – it was a walnut, which had a range of different colours in the leaves – and I was trying to capture all those variations in colour and collage them together, all in ink, in different gradients. I tried black and then green and it just wasn’t working, so I slightly felt that I was trying to – I’m always trying to come up with new work, a slightly ridiculous pressure to put on yourself, really you should just give yourself more time, so now I have gone back to doing the tree shadows. So yesterday I completed three paintings, which was a relief, because I got a bit stuck for two or three months. I do want to come back to the light through the tree canopies, because it’s been an obsession of mine for ages, since I was a kid really, when you were lying on your back on the grass looking up into the leaves with the sunlight coming through, but I can’t capture the light at the moment with the medium I’m using, so that’s why I’ve started making etchings, because the whiteness of the paper and the black ink, which becomes very matt, seems to be doing the job.

What are the challenges of your way of working ?

The etchings came about through the need to fill the winter gap. I was drawing in the winter sun, but it didn’t cast a good shadow, which I hadn’t realised, because the angle of the sun was too low. And it was a really grey winter last year, so I was waiting for the sun that never came. I did try using a lamp in the studio, but it felt wrong. It was impossible to get the light at the right angle and it felt like faking it. I am interested in capturing an ephemeral moment, not a frozen moment that doesn’t change. I have tried working from photos of shadows I’ve seen when out and about and projecting them onto the wall of the studio, and again it just didn’t feel right. I wasn’t capturing that moment that the camera had captured. And I enjoy the process of being really spontaneous. Just yesterday I had a small window to work in because the clouds were coming, and I was moving around this mock orange branch, and then the sun went, which was my fault for taking too long, which takes me back to that whole thing of not thinking and just being in the process. Every time I overthink it, it feels like I could be on that painting for weeks, and I’m not really like that as a person, so it would feel unnatural to do that.

By working with the sun I have got to know more about the passing of time, changes in daylight and seasonal changes. So I now know that autumn is coming up to peak season, because you get those amazing long shadows, which I find quite exciting, alongside the anxiety of knowing that I’m running out of time. I did do some painting in Thailand last winter. Paintings of palm trees that just looked like palm trees, and I found that quite interesting, because I didn’t know the Thai landscape, I didn’t know Thai plants, and I realised I am happier painting the familiar. Someone asked me recently why I paint hazel, and it’s simply because it’s in the hedge at the back of my studio, and it’s abundant. When I came to your place, again it was just complete overstimulation. There was so much, and I didn’t know what to choose, and your garden is very much a changing landscape. You can leave it for two weeks and come back and there will be a whole different colour palette. So when I came to your garden it just felt wrong not to paint flowers, even though in my mind I thought, ‘No more flowers. I’ve painted enough.’ It was the first time I felt like I actually wanted to paint flowers again, because I was discovering new things again, So that is something I’d like to explore more in your garden, but I need to get more used to it, as it is a whole new territory.

You told me that painting in our garden has opened up a new way of working for you. How ?

Well, the summer we’ve had this year has been very unusual. We don’t usually get weeks on end when it is just sunny every day, and I just felt like I needed to mark that. To capture the sun, and capture the flowers. So I thought, ‘How can I do that ?. So what I have noticed about your garden is that it has a lot of different shapes. All the plants have their own identity, and they all hold their own in the beds, none of them get lost. So I wanted to capture the shape of the plants, but not in ink.

With the etchings I did last winter of leaves, you just got the silhouette, and so I tried painting the silhouettes of some of your plants directly from life, and I just didn’t like the feel of them, and then the light was so amazing that that became my focus. So I started exposing the shadows onto cyanotype paper, where you are directly capturing the light on the paper. I’d first done this a few months earlier and was really interested in the process, as it produces images that are almost like abstract paintings. In some you can tell what the plant is, but in others you can’t and I like that. So the first time I tried it in your garden I was too scared to get close to the plants in the beds, and so I took the deadheaded rose cuttings off the compost heap, because I could just put them onto the paper and allow them to fall in their own way without me arranging them. I also like that element of chance. And I was also very influenced by the things you have at your place. Quite a lot of elements from Japan, a lot of natural materials and a lot of craft. And I just felt that etching, which is a craft, was a more appropriate response to the site.

So I want to create a series from your garden, but I would also now like it to be a longstanding, seasonal thing. So this summer it has, so far, been about the roses, which were such beautiful, old-fashioned looking varieties. I would like to come back at harvest time and see if I can capture that, when everything is going to seed. And rosehips. I just really want to document the seasons, as I don’t think people look at things closely enough and I think, when you’re more in tune with the seasons, you understand the world and our place in it better.

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

Lucy in the garden at Hillside in June

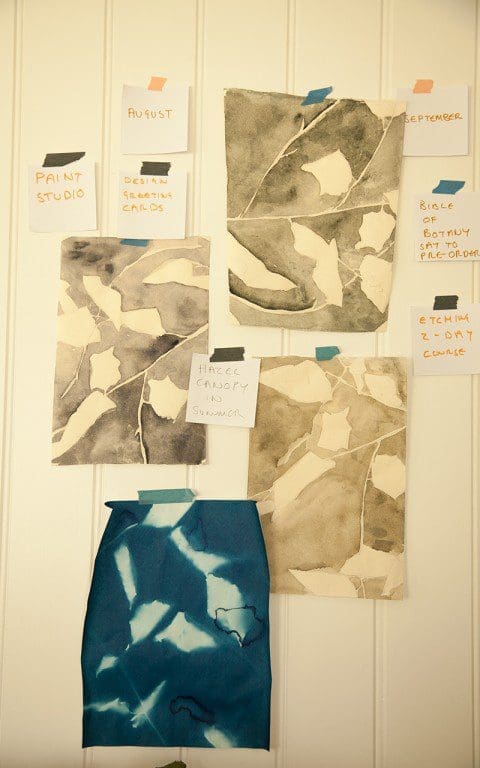

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

Some of the cyanotypes made in the garden at Hillside

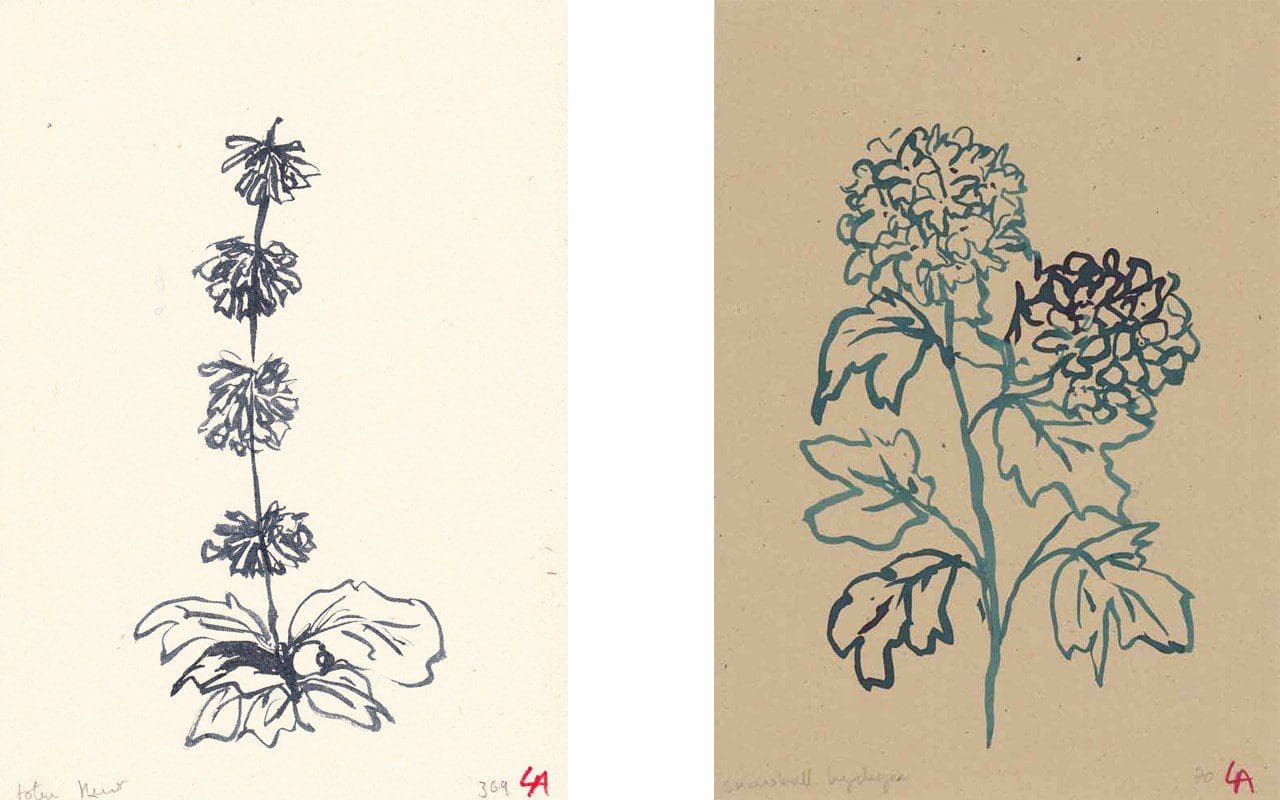

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

Etchings produced by Lucy last winter

After last winter do you have a new approach for this coming winter ?

Yes, winter will be the time when I execute all of the etchings I am going to make from the cyanotypes taken in your garden. The process of creating etchings is quite time-consuming and complex, and it is still very new to me so I would like to spend more time getting more experience of that process. So at the moment I am just amassing lots of exposures so that I have plenty to work with later. And I am also going to explore some light and dark paintings of your garden from sketches I have made. Fingers crossed I am beginning to find a good seasonal rhythm for my work.

I’m also going to experiment more with photography, and explore the uses of light more and see where I can take it. As well as stillness I’m really interested in capturing the passing of time. For example the cyanotypes I made in your garden only needed a ten second exposure because the light is so strong there, whereas in my studio I need a fifty second exposure to create the same quality of image, but that longer exposure also captures that extended amount of time. I find that fascinating, and a route I’d like to explore. I also go to Westonbirt Arboretum in the winter, as there is always something out. Going there makes you realise how much there is to look at. There’s always something in season, or that has something in its branches to explore, and then you really are looking at winter. But I think your garden has a lot of winter interest, which I am looking forward to.

I also want to focus on the work without the pressure of a show, and just have a process for a while and see where things go, like the exhibition at the Garden Museum, who you introduced me to, and which came about very organically. I would like to be a bit more relaxed and take more time.

Do you have any burning ambitions for projects ?

I would love to be commissioned to create a stained glass window in a church. I’m not religious, but because I work so much with light, I could really see my work translating into stained glass effectively, with sun streaming through. I’d love to work with a craftsperson to do that. And I’d really love to create a design for the Chelsea Flower Show poster, which has always been something I’ve wanted to do. And I would love to do a residency in Japan.

Lucy’s work is available to buy from a catalogue on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan / Photographs of Lucy and studio: Huw Morgan. All others courtesy Lucy Augé.

Published 25 August 2018

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage