ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

When we arrived here, we took back some of the field to make a trial garden. It was workmanlike in its layout, with dirt paths between manageably sized beds and functioned as a test ground to see what the conditions here were capable of. We grew a range of perennials to see what would feel right and do well on our south-facing slopes as well as vegetables and flowers for cutting for immediate rewards in that first exciting growing season.

The annuals were the immediate litmus, rearing out of virgin ground where they were bathed in sunshine. The response was immediate and immediately rewarding, the cabbages bulking up to a couple of feet across and letting us know exactly why this had once been a market garden and that, yes, it was right to turn field back to garden. For fun, and as a celebration of this new space, we planted a bed of five or six types of sunflower. They grew like you remember things growing as a child, the seedlings popping through the newly turned dirt and not looking back as they raced skyward. I hadn’t seen growth like it and before long they were standing literally twice as tall as me and rejoicing as we were in this wonderful new ground.

We picked them by the bucket and took vigorous bunches back to the studio in London to tide us over during the week and stop us pining for the hillside. They kept us going through July and were at their peak in August, reminding me by the end of the month of that back to school feeling. The time of the year when the summer is nearly done, but still caught in their energy.

In September we let them form seed and those that didn’t get ravaged by an October storm stood blackened by frost, the seed cases scattered at their feet where the birds had feasted. Seedlings returned in the garden and I left them where I could work around them in the following years, but when we developed the kitchen garden to the east of the house and then the perennial garden to the west, they temporarily lost their home.

Last year’s response to the pandemic saw us putting up a polytunnel so that we could extend our season of growing to eat. This year I extended a new growing area around it to make an area for continued trials and a spill over for vegetables that need more space. Potatoes were planted to ‘clean’ the ground in this first year of transition from pasture and to repeat the experiments from our first years here we planted a new bed of dahlias, annuals for cutting and sunflowers. It has been so very good to have them back and in generous amount, once again letting us know that, yes, this is a good place for growing.

We have three varieties of Helianthus annuus that have done splendidly. ‘Lemon Queen’, ‘Velvet Queen’ and ‘Chocolate Cherry’. This will be the last year though that we grow ‘Italian White’, a more demure variety that has proven once again to be a shadow of its cousins. Perhaps it is my own experience and I have been unlucky, but every time it germinates poorly and then limps through life. Shy is appealing sometimes, but when you have such boisterous cousins that literally throw you into shade, it makes comparison difficult.

As a complement and for the saturation of pure orange, the Mexican Sunflower, Tithonia rotundifolia, has been easy and rewarding. Grown from seed sown inside and planted out after frost, we have combined it with lime green Nictotiana langsdorfii. The new ground is here to spur ideas and a few plants, the Tithonia included, have already found their way into the perennial garden to punch some late indelible colour. Annuals are good for that, taking this month as their own with no apologies and covering for anything that tends to that back to school feeling.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 August 2021

Nothing smells like early summer quite like a sweet pea. Fresh and intoxicating, innocent and sensual in equal measure. The scent of my grandparent’s garden, which wafted through the windows of my bedroom on hot summer nights in Swansea. The vines planted at the ends of the runner bean supports, which brought the sweet peas down to earth while exalting the beans. They were never cut for the house, just allowed free reign to scramble and scent the vegetable patch. Now that I grow my own the house is filled with their scent as long as I can keep up with picking them, although there is always a point in the summer where the stems get so short or you have better things to do (like bottling tomatoes, freezing soft fruit, making jams and chutneys) that it is finally better to leave them on the plant and allow them their natural decline.

This year, for the first time we got our sweet pea seeds sown early. Before the arrival of the polytunnel we had always waited until late March before sowing, but we got a head start this year and planted them in early-February. The seeds were soaked in cold water overnight, which is reputed to make them faster to germinate, although it is difficult to ascertain whether this is the case or not. Three seeds of each were sown in a 9cm pot with two pots of each variety and put into our unheated toolshed, which has the frost kept from it by virtue of also being where the boiler is located. When we posted news of the seed sowing on Instagram some queried why we weren’t using root trainers and, although it is true that all legumes tend to benefit from deep pots due to their searching root growth, we have never had an issue with pot-grown sweet peas, as long as you get them in the ground before they become pot-bound. That said we have been collecting the insides of our toilet rolls to use next year to see if it makes a difference.

As soon as the seeds started to germinate they went into the Milking Barn, where we have a dedicated propagation shelf set up in the picture window, which gets direct light for most of the day. A week after germination, to prevent them becoming etiolated, I would ferry them down to the polytunnel every morning to get as much light as possible, before bringing them back up to the heated barn every evening. By early March the polytunnel was warm enough to leave them in there overnight and soon they were large enough – with four sets of true leaves – to pinch out the tops, which encourages strong root growth and stockier plants.

Once the seedlings had reached a height of 15cm they were brought up to the cold frames by the barns and hardened off for a week before planting out. However, this was delayed by the prolonged frosts in late March and early April and so, when we did eventually get them in the ground in the second week of April, they were protected with fleece for a few days until the cold snap had passed. Sweet peas are hardier then they look and although one frost was hard enough to get through the fleece, despite their wilted appearance the plants recovered very quickly.

We have grown sweet peas every year since we moved here and have tried a wide range of varieties, but we always return to the Old Fashioneds and Grandifloras. These are the smaller flowered varieties, many of which are very old, and which have the strongest scent. They have a tendency to shorter stems, which means that they are not so popular with flower arrangers and florists, but I simply cut longer stems from the plants with leaves and tendrils intact. The Modern Grandiflora varieties were bred in the 20th century to provide the scent of the old varieties with the larger flowers and longer stem length of the more popular Spencer types, which have large, more ruffled flowers and long stems, but little scent. As with roses there seems little point in growing sweet peas unless they overpower with perfume.

I’ve tried several of the text book methods for prolonging the flowering season, including one year following the wisdom of the professionals and pinching out every single side shoot to encourage upward growth which, when it reaches the top of the hazel poles, is then trained down the neighbouring pole to double the height of the plant and, therefore, the number of flowers it produces. All very educational, but frankly life’s too short. Now I simply ensure that each time I pick a flower (and regular, daily, picking is the best way to ensure longevity) I snip out the side shoot that develops at its base, as the energy required for these prevents the main stem from reaching its full height and the flowers produced on them always have much shorter stems.

Each year we plant a range of colours and, although we have some stalwart favourites like ‘Cupani’, ‘Painted Lady’, ‘Almost Black’ and ‘Lord Nelson’, we always trial some new varieties. Here is this year’s selection.

Words and photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 26 June 2021

I first encountered Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’ around twenty years ago at Stoneacre in Kent. At the time our recently made friends Richard Nott and Graham Fraser were the National Trust’s tenants and, as its custodians, they had woven a thoughtful new layer into the garden that played to their interest in colour. They had recently exchanged their lives running Workers For Freedom, their successful fashion label, for a new life in the country. Richard was studying painting and Graham, the history of both the garden and the house, which was restored in the 1920’s by Aymer Vallance, the Arts & Crafts architect and biographer of William Morris.

Together they took to the garden, moving easily from one creative discipline to the next, enjoying the fact that the worlds were easily interchangeable. It was precious time that we spent there and, with weekends away from our south London lives, in the idyllic setting of this place it felt like there was time to talk. We workshopped the planting and in the easy world of this garden the conversations moved effortlessly back and forth to cover all manner of territories. With life experience that we were yet to have, our new friends provided good council and helped build confidence about doing what was right for us and being sure of our direction.

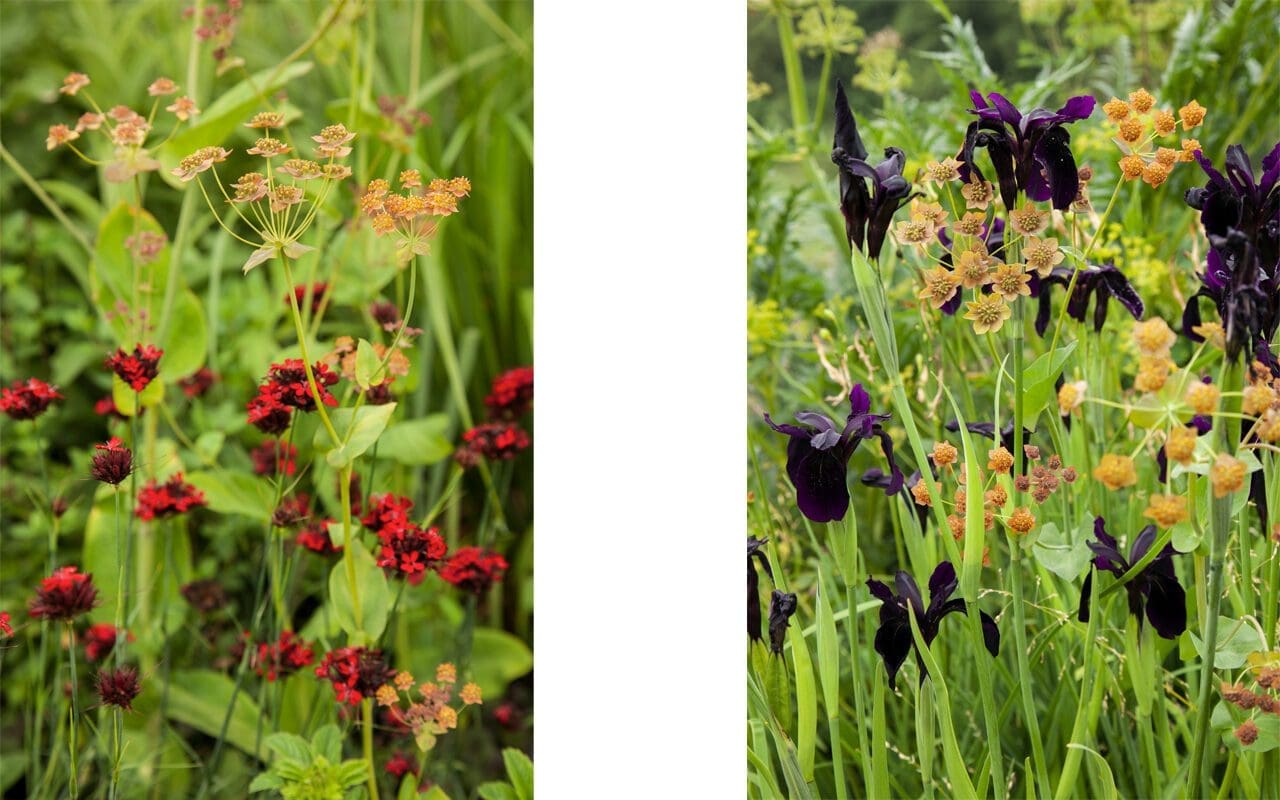

Stoneacre is a garden of rooms that give way one from the other as you walk around the half-timbered hall house. A straight stone path sloped gently to the front door and they had dug up the lawn to either side and planted a pair of gauzy, golden borders that rose in early June to shoulder height with the shimmer of giant oat grass (Stipa gigantea). As you walked the path the detail in the planting revealed itself. Hemerocallis ‘Corky’, a delicate daylily with a dark reverse to the petal, provided the base note of gold. There was saffron Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora ‘George Davison’ and later Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’, but there was a secret ingredient that provided the planting with a burnish. The bupleurum hovered amongst it all as a mutable undercurrent, a presence that was hard to detect at first until you had tuned your eye, but once you had it, it was the thing that drew you in and held you.

A clutch of seedlings found their way back to the garden in Peckham where they seeded about obligingly. Never moving further than the cast from a bent stem in high summer, but finding their niche wherever they like the territory, the tiny seedlings are easily distinguished in spring. Brilliant lime green cotyledons, two narrow slashes, appear early in the season. They arrive in a rash where they find open ground and soon form a bright first leaf the shape of a paddle. Where there is light and not too much competition they spend their first year hunkering to form a neat rosette. In the second year they throw the first flowering growth, sending up slender stems in early summer with a dusty bloom that softens their presence. By the middle of May the first umbels are filled out and standing tall and free of foliage. Finely spoked they throw just enough florets skywards, each with a neatly cut ruff and an inner button of stamens.

The shifting colour of ‘Bronze Beauty’, the form most commonly available, is hard to pin down ranging as it does from cinnamon to ochre to tan, but it compliments everything. I have not found a companion I do not like it with. I will determine a combination that I think will work well, but its easy nature will throw it into new territory together with something you simply hadn’t or wouldn’t have thought of. I am very particular about colour, but I rarely find it appearing anywhere that I find it jarring or out of place.

Advice if you are reading up about Bupleurum longifolium is to plant it in an open, sunny position. Yes, the low rosette enjoys light and suffers if it is overhung by neighbours, but we have found here, where we have all day sunshine, that it prefers to set seedlings on the shady side of the bed and those in full glare do less well. I think ‘open meadow’ when I plant it, so that it can rise up in company, but not so much that it feels overcrowded.

Although it is now finding its own way in the garden and is never competitive like its acid-yellow cousin, Bupleurum falcatum, which we also grow, the plants last three to five years and then hand over to the next generation. I always have a pot full of seedlings in the frame for good measure. They make easy additions where you might suddenly find yourself with a gap come spring. Always sow fresh, as all umbellifers (Apiaceae) do not last if kept and overwinter with a little protection. It was one of these pots of seedlings that found their way back to Richard and Graham a few years ago when they left Stoneacre to make their own garden at a new home on the south coast. An easy gift to return for such a treasured introduction.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 13 June 2020

The opium poppies have been growing into the lengthening evenings, to race skyward and seize this early window of first summer. They come from nowhere it seems and typify the current feeling of the garden burgeoning.

Their seedlings are already visible in March and one of the first to germinate into open ground. Blue-green and easily distinguished, they take the disturbed places where there will be a gap to ascend into the very moment the weather warms. Being winter hardy and germinating the moment the season turns with the promise of spring, they have the advantage, hunkering down and establishing good roots and core strength. In truth there are several rounds of germination as seed is brought to the surface whilst cultivating, weeding or clearing the winter garden to expose fresh ground, but the first are the strongest, bulking up in April and muscling out anything nearby that might show a glimmer of tardiness. Their precocious behaviour extends to their siblings and you will need to thin a colony if you are after plants that are muscular and soaring.

I grow a black opium poppy here and it is my one and only. A single form and a chance find that I made when cycling to work once in my early twenties. They were standing tall alongside a black wooden bungalow in Hampshire. Black on black, fluttering against the stained shiplap. If I hadn’t been looking in the way that you do when you are under your own steam, I would have missed them completely. It was immediately clear, even at distance, that they were special so I plucked up the courage and knocked at the door to ask for seed. The owner, seeing I was smitten, took my name and address and later that summer an envelope arrived with the beginnings of a now very long association. It is one that I have nurtured annually, seeding a few every year in a new place for good measure and gifting to friends and clients that I know will keep the strain pure.

Although there are other named forms of dark opium poppy, several double blacks and the deep plum ‘Lauren’s Grape’ for instance, I’ve not seen another that is quite as dark and inky throughout. To maintain the strain, I have been territorial. I have never introduced another coloured opium poppy into a garden where I have been cultivating them and any that show the remotest sign of reverting are pulled before they can pollinate a dark one nearby. I look nervously on to neighbours up the lane who have them growing freely in their garden in every shade of mauve and pink, but breathe easy that, in the ten years we’ve been here, the bees that busy themselves there must be on another flight path.

After moving them here from Peckham, I cast the seed down into the freshly turned ground of our virgin plot. Broadcast in February, the plants were up in flower by June and providing me with a new and plentiful seedbank by the middle of July. Those seeds have now found their way into the compost heap where they are content to sit dormant until they are exposed again to light and potentially new places to conquer. We had a good colony in the asparagus bed a couple of years ago, amongst the roses and throughout the kitchen garden and I am now finding seedlings in the paths that must have been dropped whilst we were clearing the garden.

The chance happening of the pioneer seedling is always heartening and we leave a few in a new place every year for the delight in the new. The first seedling to flower this year has been living with us closely alongside our covered terrace. I saw the seedling had found a home in the late winter and wondered if it would be one that would survive our lines of desire into the garden. It has, soon growing big enough to negotiate and with the promise of this very moment that is seeing it suddenly present. A filling out of blue-green buds and then, one day, a tilt in the neck of the bud to indicate readiness.

The mornings bring the flowers, crumpled at first and then expanding like dragonfly wings do when they hatch. Dark satin petals cup pale stamens and bees soon find them, noisily working in laps, the enclosure of petals amplifying the sound of their frenzy. The flowers last two to three days at most, but there are enough to run a glorious fortnight whilst the balance shifts from buds to seedpods pods fattening and tilting skyward to show you that they have nearly reached their goal. When the leaves suddenly wither and the life force of the plant is gone you see that the pepper-pot seedpods are ripe and beginning to rupture. We leave a few standing for the joy of continuity, the mission accomplished, and scatter the rest for the pleasure of helping them extend their territory.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 30 May 2020

The garden has taken a distinct and irreversible turn. It is not a sad thing, just the beginning of another season. A slowness in the Morning Glories, that just a fortnight ago were still racing skyward and now stay open well into the afternoon in defiance of their name. Kaffir lilies flaring hot colour and the first spears already pushing on the Nerine.

A gentle countermovement happens alongside the feeling that most things have reached their peak and are now ready to begin standing down. When we lived in London it was the Datura which went for its best and most intoxicating September fling. Primed by the cooling weather and definitely responding to the onset of autumn, it had been readying itself for such a finale, which, in the shelter of our Peckham garden, would run through to November and test my resolve in leaving the plant out just for one more night. I have an offspring of the very same plant here, treasured but never thriving on our windy hillside. Though I have moved the pot around to try and find it the shelter it needs, this hothouse flower knows its limits and taunts me here rather than rewarding.

Not so the Nicotiana suaveolens which right now is having a moment. This is another plant that I have grown continually for what must be at least twenty years. I first knew it as Nicotiana noctiflora, in reference to its night-flowering habit, and have a niggling half-memory of where it originally came from, which is surprising considering my devotion. Derry Watkins of Special Plants was here recently and said that it was one of her all-time favourites too, but that she never saw it any more. She used to grow it for sale, but the plants were seldom bought. When I asked her why, she said that she thought it was too subtle for most people. Its quiet elegance is exactly why I love it.

I have explored the tobacco plants over the years. Towering Nicotiana mutabilis, with a confetti of tiny flowers, suspended in a cage of branching stems, which age from white through palest pink to deep rose. Where there has been a need for an exotic moment, Nicotiana sylvestris has provided lush foliage, a bolt of white drama and heady perfume. The tiny, green bells of Nicotiana langsdorfii have been mingled amongst perennials to extend the season in the borders and I currently have a little trial of dark-coloured varieties, which I imagine must have some N. langsdorfii in their blood. ‘Tinkerbell’ has lime green trumpets with a rust-ruby face and unexpected blue pollen. ‘Hot Chocolate’ is similar, but a velvety brown-red. Subtle beauties that need to be placed carefully if their colour is not to be lost.

In Peckham we suffered from the dreaded tobacco mosaic virus, which is carried on tomatoes and affects their solanaceous cousins when in full swing. When it hits, the Nicotiana leaves firstly develop the distinctive mosaic patterning, then they begin to twist and melt, leaving the plants failing in high season with a wide open autumn ahead of them and the associated disappointment. Interestingly, the Australian Nicotiana suaveolens was never affected and, even when growing alongside others that did succumb, it soldiered on until the frosts. I brought it here as seed, which is produced in plenty and is easily reared from a March sowing under glass. Where it has seeded into pots that spend their winter in the frames, I’ve found it to germinate spontaneously in April as the weather warms. The seedlings that make their own way without transplanting catch up with those that are pricked out and cossetted.

In London our plants would return for a second and sometimes even a third year if their spring regrowth wasn’t decimated by slugs. Though I plant out a dozen or so as gap fillers close to the paths, we have too much winter here, but our most splendid plant is growing just under the eaves of the open barn. I presume the ground is dry enough in winter to afford it enough protection to have returned a second year and at twice the size from the reserves of a decent set of roots. I noted the frosted rosette looked green in March when winter turned and looked after it accordingly to guard it from slugs.

Our barnside plant has been gathering in strength over the summer, pushing out flower since July. The wiry stems set the long trumpets free of the basal foliage and the flowers appear with room between them to hover. During the day, from mid-morning onwards, they hang in repose so that you hardly notice them, but as evening descends they awaken. Part of their nocturnal glory lies in their paleness, which is luminous in darkness and this is when they throw out their lure, pulsing perfume to attract moths and other night time pollinators. When we returned from London on Thursday night, the misty air was still and the open barn had captured this heady, exotic perfume. A smell reminiscent of cloves and jasmine that conjures somewhere very different from our cool, dampening autumn.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 September 2019

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage