With the vegetable garden either too frosty or wet to work I finally got round to sorting out my boxes of vegetable seed this week, with a view to being as organised as possible for the coming season. Yesterday was the last day of the fourth annual Seed Week, an initiative started in 2017 by The Gaia Foundation, which is intended to encourage British gardeners and growers to buy seed from local, organic and small scale producers. The aim, to establish seed sovereignty in the UK and Ireland by increasing the number and diversity of locally produced crops, since these are culturally adapted to local growing conditions and so are more resilient than seed produced on an industrial scale available from the larger suppliers. The majority of commercially available seed are also F1 hybrids, which are sterile and so require you to buy new seed year on year as opposed to saving your own open pollinated seed.

I must admit to having always bought our vegetable seed to date, albeit from smaller, independent producers including The Real Seed Company, Tamar Organics and Brown Envelope Seeds. However, last year the pandemic caused a rush on seed from new, locked down gardeners and the smaller suppliers quickly found themselves unable to keep up with demand. If you have tried ordering seed yourself in the past couple of weeks you will have found that, once again, the smaller producers (those mentioned above included) have had to pause sales on their websites due to overwhelming demand. Add to this the new import regulations imposed following Brexit, and we suddenly find ourselves in a position where European-raised onion sets, seed potatoes and seed are either not getting through customs or suppliers have decided it is too much hassle to bother shipping here. This makes it more important than ever to relearn the old ways of seed-saving so that we can become more self-sufficient.

Many of our neighbours found themselves in the same position last March and so we created a local gardeners’ Whatsapp group to let each other know what surplus seeds we had and, once the growing season had started, when we had excess plants to share. We discovered that there were a number of young inexperienced gardeners locally who were keen to try growing their own, and it felt good to be able to give them a head start with our well-grown plants which might otherwise have ended up on the compost heap. As the season progressed messages pinged back and forth across the valley and when we were out walking we would spot little trays of seedlings and plug plants left by gates wrapped in damp newspaper, waiting to be collected to go into somebody’s vegetable patch. The cabbages, kales, tomatoes and beans we couldn’t gift to neighbours were left by our front gate with a ‘Please Help Yourself’ sign, and would be gone by evening. There was something very connective about this, despite the distance we all had to keep and the clandestine nature of the exchanges. A way of binding our little community together at a time when we were all reeling from the isolation of our first lockdown.

For the first time last summer, and with an eye on the likelihood of continuing supply problems, I started to collect seed from our own crops. As a novice I began primarily with the herbs, which don’t cross pollinate, and so now have my own seed of parsley, coriander, dill and chervil for this year’s sowings. There is also a pot of mixed broad bean seeds saved from the oldest pods before they were thrown on the compost heap, and which I will be sowing in a few weeks. Although they may have cross pollinated, since we always grow a couple of varieties, this is not necessarily a problem if you are just growing for yourself, although any plants that don’t come up looking strong and healthy should be discarded. I am planning on getting seed of our own beetroot this year (which is a little more involved as they will cross pollinate with other varieties and chard, so the flowering stalks must be isolated) and lettuces, which tend not to cross and so are easier to manage.

Last spring we had a very dark-leaved lettuce come up in the main garden from seed that had made its way from the compost heap. This looked to be ‘Really Red Deer Tongue’, which we had grown the previous year. Dan thought the foliage was such a good colour with the Salvia patens that it was allowed to flower, and we are now waiting to see if a rash of dark seedlings appears when the weather warms. Some will be kept in place and others transplanted to the kitchen garden when big enough. I am also keen to try keeping our own pumpkin seed this year, which will involve isolating individual flowers and hand pollinating them before sealing them with string to prevent insect pollination.

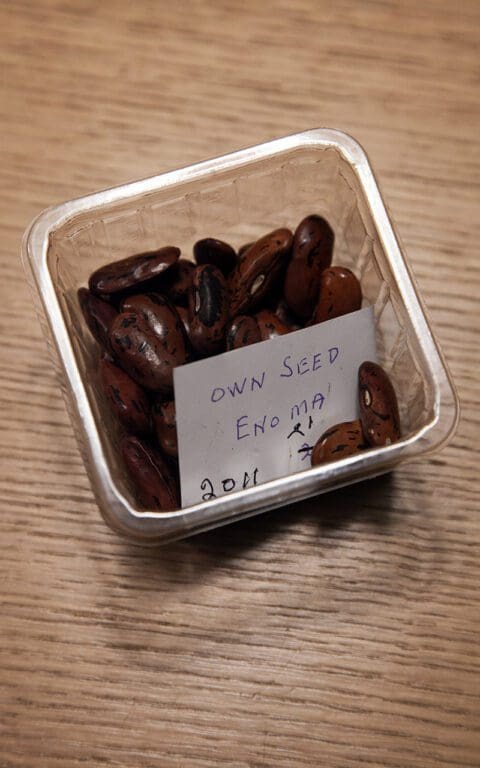

When sorting through my seed boxes a few weeks ago I turned up a small container of seed of the runner bean ‘Enorma’ collected by my great aunt Megan in 2011. Megan had been a Land Girl during the Second World War and was the most impressive kitchen gardener I have ever known. The long and steep, upwardly-sloping garden behind her house in Swansea was entirely given over to vegetables and fruit. She was completely self-sufficient in what she needed. Whenever you paid her a visit the house would be deserted and she would be in the garden come rain or shine, unless, of course, it was Sunday.

The last time I saw her at home – just a year before she became too frail, at the age of 96, to remain there – I walked up the three sets of precipitous, narrow brick steps to the garden to find her. I couldn’t see her anywhere so, in a momentary panic and picturing a senior accident, called out her name. There was a sudden movement at the periphery of my vision and Megan stood bolt upright, having been doubled over the trench she had just dug and into which she was carefully placing cabbage plants. “Just a sec!’ she shouted in her mercurial, high-pitched voice that was always on the brink of a giggle, and finished planting the row. She walked towards me, brushing the soil off her hands onto the brown checked housecoat she wore to garden in. “Well.’ she said. ‘What a lovely surprise! Do you want some tomatoes?’ Although she couldn’t stand to eat them, Megan had a greenhouse full of them, because she thought they looked so beautiful and she enjoyed giving them away to neighbours and friends. Needless to say she was green-fingered and I think a big part of the pleasure for her was knowing that she could grow them so well. She picked me a brown paper bag full and, as we left the greenhouse, I complemented her on her towering runner beans. ‘Oh, you can have some seed of those. ‘Enoma’,’ she said, missing out the ‘r’ and went to rummage in the shed for a moment.

This year, almost eight years after Megan died at the age of 98, I intend to plant her home-collected seed. A way of connecting me to the Welsh family that has gradually dwindled over the years and, perhaps, some of Megan’s skill and stamina will rub off on me along the way. Saving and sharing creates these connections between family, friends and strangers. It feels like nothing is quite as important as that right now.

The Real Seed Company give very clear advice on seed saving in two booklets available to download for free from their website here.

Words & photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 23 January 2021

Previous

Previous

Next

Next