The market gardens that originally striped the slopes here were given over to beef cattle about fifty years ago. The farmer had a dozen or so animals and the fields were grazed to the very edges. Lengths of rusty barbed wire kept them from venturing into the stream and pushing through the hedges, the branches on overhanging trees were cut back right to the boundaries and the hedges kept trim so that the ‘grub’ was given all the light it could get. The grass was everything.

Our first winter here we resolved to put a number of the fields back to meadow. This was not necessarily an easy decision, because the best flower meadows are the result of many years of appropriate husbandry: namely the removal of the hay crop, which diminishes soil fertility, followed by winter grazing by livestock. The high ground where the limestone brash broke through provided us with the best chance of diversity, while the lower ground grew grass that was lush and constantly emerald green. We found out from neighbours that our top fields above the lane (main image) had once been known as the Hospital Fields and that sickly cows were sent there to self-medicate on the plants that were good for them. Even before the fields were allowed to grow out the following summer, we could see here the knit of rosettes amongst the sward and the marked contrast in plant diversity compared to the lower ground

Yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor

Yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor

The next autumn we over-sowed these fields by hand with meadow seed gathered from the neighbouring valley. The seed is harvested annually from the well-established meadows of St. Catherine’s valley by Donald MacIntyre of Emorsgate Seeds and the technique of over-sowing enabled us to increase the diversity in our own fields without needing to disturb the ground. The key component in the seed mix is yellow rattle, Rhinanthus minor, an annual which is semi-parasitic on grass. The rattle is invaluable for its ability to open up the sward by diminishing the strength of the grasses and thereby allowing the broadleaves – and most importantly our new seed sown directly into the existing sward – a window of opportunity to establish. Without it the over-sown seed would stand little chance of competing.

Yellow rattle is particular in its habits and needs to be sown between mid-September and Christmas at the very latest so that the frost can break the seeds’ dormancy. Winter ‘poaching’ of the fields by livestock presses the seed into the soil and makes for the best establishment, so we let the sheep into the fields to trample the ground and bring some mud to the surface. You can simulate this by first scarifying the thatch and then rolling the ground after sowing, but sheep do a better job and keep the grass short over winter, so that in March, when the rattle germinates, it has the head start it needs to get away early.

Oversown St. Catherine’s meadow mix behind the house after three years

Oversown St. Catherine’s meadow mix behind the house after three years

Trying to spot the seedlings the next spring became the stuff of obsession, both of us tramping the fields, heads bent, looking for the first distinctive serrated leaves, but Donald, who gave us the seed, said that for every one you see there are a hundred that you don’t. It was good advice, along with waiting until the 15th of July before cutting the hay, so that the rattle has the best chance to drop its seed. An old adage goes that when the rattle rattles the hay is ready for cutting and, sure enough,when it is ripe you will hear the seed rattling in the bladder-shaped seedpods . You can knock yellow rattle out of a meadow by cutting too early, as it is an annual and the seed is only viable for a year.

Increased floral diversity including ribwort plantain, black medick, red clover and pale flax

Increased floral diversity including ribwort plantain, black medick, red clover and pale flax

The following autumn we over-sowed The Tump, a field lower on the slopes and higher in fertility. The rattle has had a harder time here making its way into the grasses, but where it has taken we are seeing a greater and improved diversity of species. With every year we see the results in the wake of the yellow rattle with a notable presence of plantain, red clover, buttercup and rattle colonies in the second year. After five or six years the yellow rattle reaches a climax and starts to out-compete its host grasses and suddenly disappears to relocate elsewhere in the meadow. The results of the over-sowing have varied according to the differing ground conditions and it will take a decade before we really know whether the richer ground is suitable for supporting the species-rich meadow that should be possible on our thinner soil.

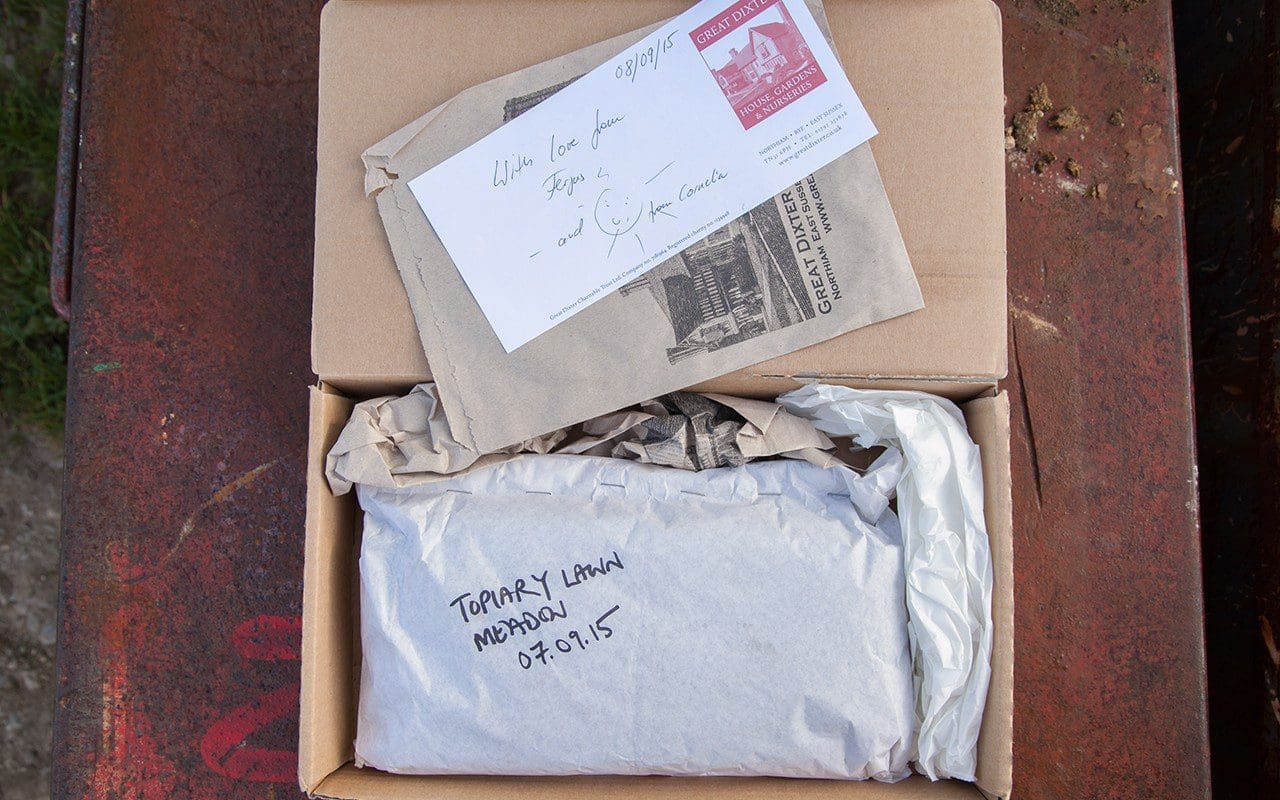

Package of Great Dixter meadow seed sweepings

Package of Great Dixter meadow seed sweepings

Over-sowing the Great Dixter meadow seed last September

Over-sowing the Great Dixter meadow seed last September

In year three, I sowed directly onto subsoil where we had stripped a level on the banks behind the house for topsoil. The newly sown ground has lower nutrient levels and sowing directly onto subsoil means that the strength of the grasses is automatically diminished. I made my first attempt to introduce orchids into this new area last September with a gift of the orchid-rich sweepings from the topiary meadow at Great Dixter, which were given in exchange for a lecture I gave there. Christo famously once responded to a request from a visitor that the meadow sweepings were not the sort of thing that money could buy, so it felt appropriate to barter. The contents of the package looked like nothing more than straw and dust, so I chose a still day to broadcast it and then let the sheep over the ground to crop the meadow short over the winter. If we are successful – a seven year wait will be necessary to see – it will be because there is a mycorrhiza in the ground that is symbiotic with the orchid roots and crucial to their establishment. A solitary pyramidal orchid blooms on the bank nearby, so I am ever hopeful.

Our solitary pyramidal orchid, Anacamptis pyramidalis

Our solitary pyramidal orchid, Anacamptis pyramidalis

This month, and to bring the meadows close, I have sown the newly contoured landforms around the house which have been made up with subsoil from the building works. After grading earlier this summer I deliberately left the ground dormant to flush out any weeds ahead of the meadow seed germinating and thereby diminishing competition from unwelcome interlopers. Annual weeds will be knocked out with a hoe and perennial weeds, such as creeping thistle and bindweed, selectively spot-treated with glyphosate. This and next month are the optimum time to sow, with heat in the ground from the summer and the promise of damp in the air to get the newly germinated seedlings established and knitting together before the onset of winter.

The yellow rattle seed gathered this year is broadcast to areas where the grass grows most strongly in the meadows

The yellow rattle seed gathered this year is broadcast to areas where the grass grows most strongly in the meadows

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Previous

Previous

Next

Next