ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

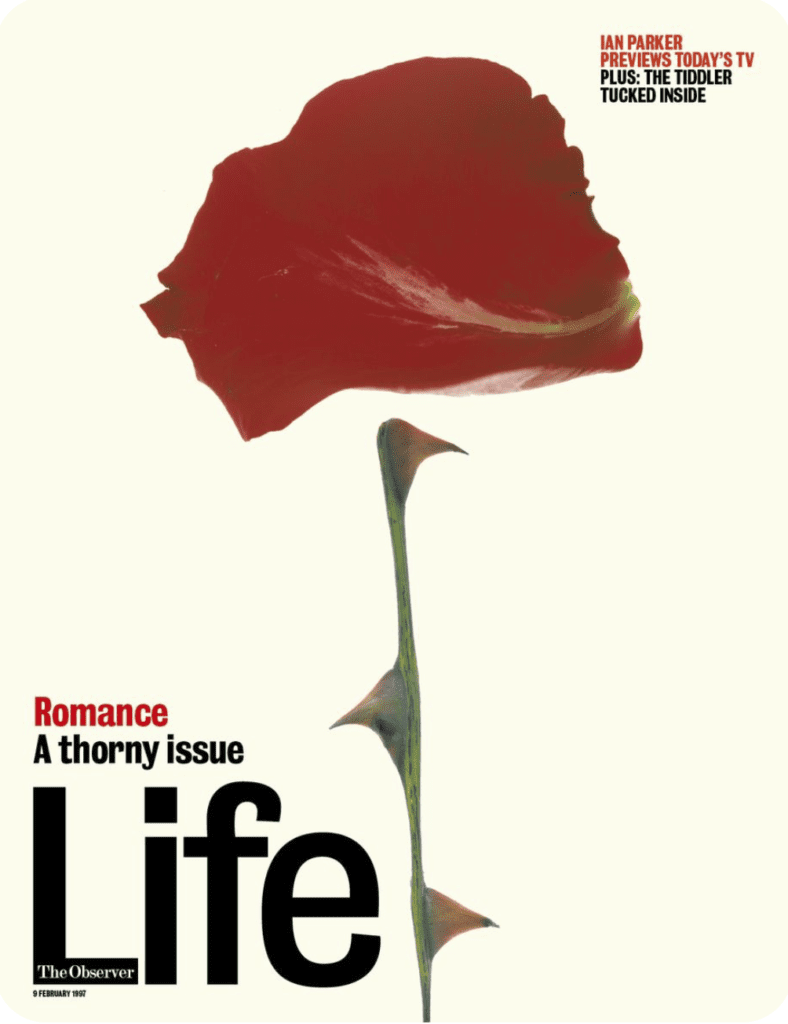

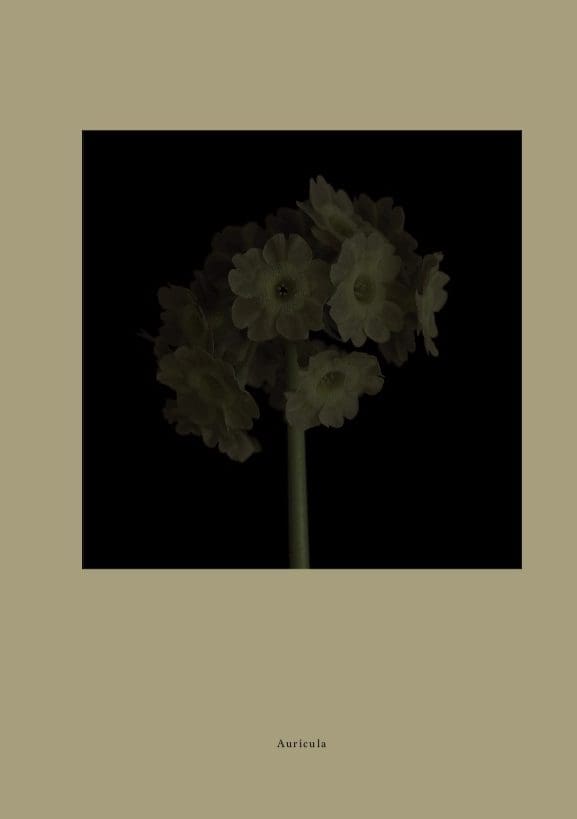

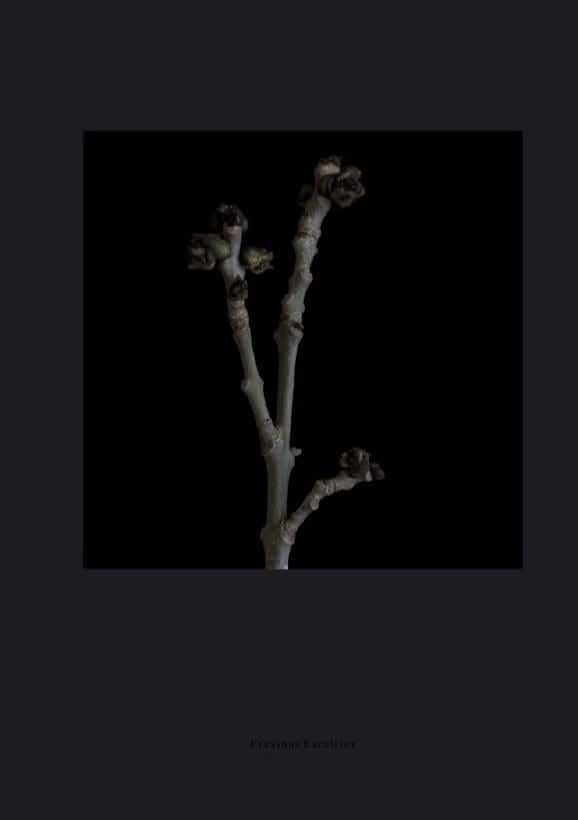

Fleur Olby first came to our attention in the 1990’s with her striking abstract plant portraits which illustrated Monty Don’s gardening column in The Observer Life Magazine. Her interest in shooting in low light prompted us to invite her to photograph the winter garden. So, early this year, and just weeks before lockdown, Fleur came to spend a day and a night at Hillside. As the clocks go back we revisit her vision of the penumbral garden.

Tell me about your interest in nature. When did it begin and were there any key experiences that shaped your relationship to the natural world and plants in particular?

During childhood I became ill with double pneumonia and had to be in an oxygen tent. My Mum brought an oak leaf into the hospital as a gift to look at something beautiful and magical from a tree close to where we lived and the thought of visiting it when I was better. I remember visiting the tree later, although now it all feels dreamlike. There was something then that I still question in the shift in perception of looking at something small in isolation to seeing it in its context of growing on a tree. The enlarged gaze of a child was full of wonder, magic and intrigue, something I have tried to recreate in my still life photography.

How did you realise you wanted to become a photographer?

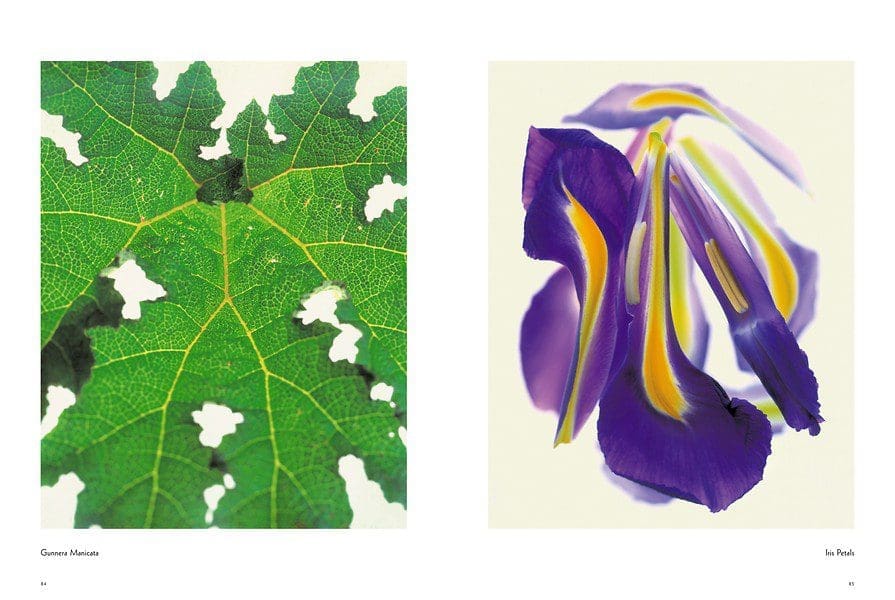

During my MA in Graphic Design at Central St Martins (1992), I spent a lot of time colour printing in the darkroom, my degree show became purely photographic – Images of environmental and flower still life. My thesis explored the different ways of looking at Nature from abstraction, the single image, still life, the object in its environment, the concept of the Wilderness and a Garden and their uses within the industries of Art, Design and Photography.

I wanted to be able to work within the landscape I grew up in and the magazine aesthetics of still life. At this time, I was entranced by looking at detail, but importantly when I first started making pictures in wilderness places there is an unexplainable feeling found through the camera.

Your work for The Observer Magazine was groundbreaking at the time. Can you explain how your view of plants differed from the norm then?

I was inspired by Monty Don’s writing and both degrees were fine art graphic design – lighting and composition were always experimental. Nick Hall was my first commissioning editor at the Observer and then Jennie Ricketts. He commissioned the garden articles to be an abstraction in still life. The concept of the garden as a still life representation was different then. It was a unique time when my imagery was young and given total creative freedom. For the articles, I would regularly be at the flower market at 4 am and in the lab processing the work at midnight ready for the morning.

Although you were working commercially what made your photography stand out then was that it was clearly the vision of an artist. Can you describe you and your photography’s relationship with the worlds of art and commerce and do you still produce commercial work?

I had a good mix of editorial design and advertising and the two books were the fine art application of my work. After the 2008 financial crash and the evolution of digital capture still-life Photography commissions changed and lifestyle photography replaced a lot of the still life work. After 15 years of commissioned work, I had to change my practice as it became unviable to run a still life studio. I consolidated my archives and started to make personal work. The series are ongoing, but I would also like to work on plant collections again and garden stories.

How did your work develop after your time at The Observer ? I have read that some of the images were used in installations. Now you produce limited edition imprints alongside prints.

The Observer gardening editorial was amongst editorials I contributed to regularly for food and health and beauty. When I stopped shooting for the gardening articles in 2002 the food still life increased and I also worked for some fashion companies for still life and jewellery, perfume and interior still life.

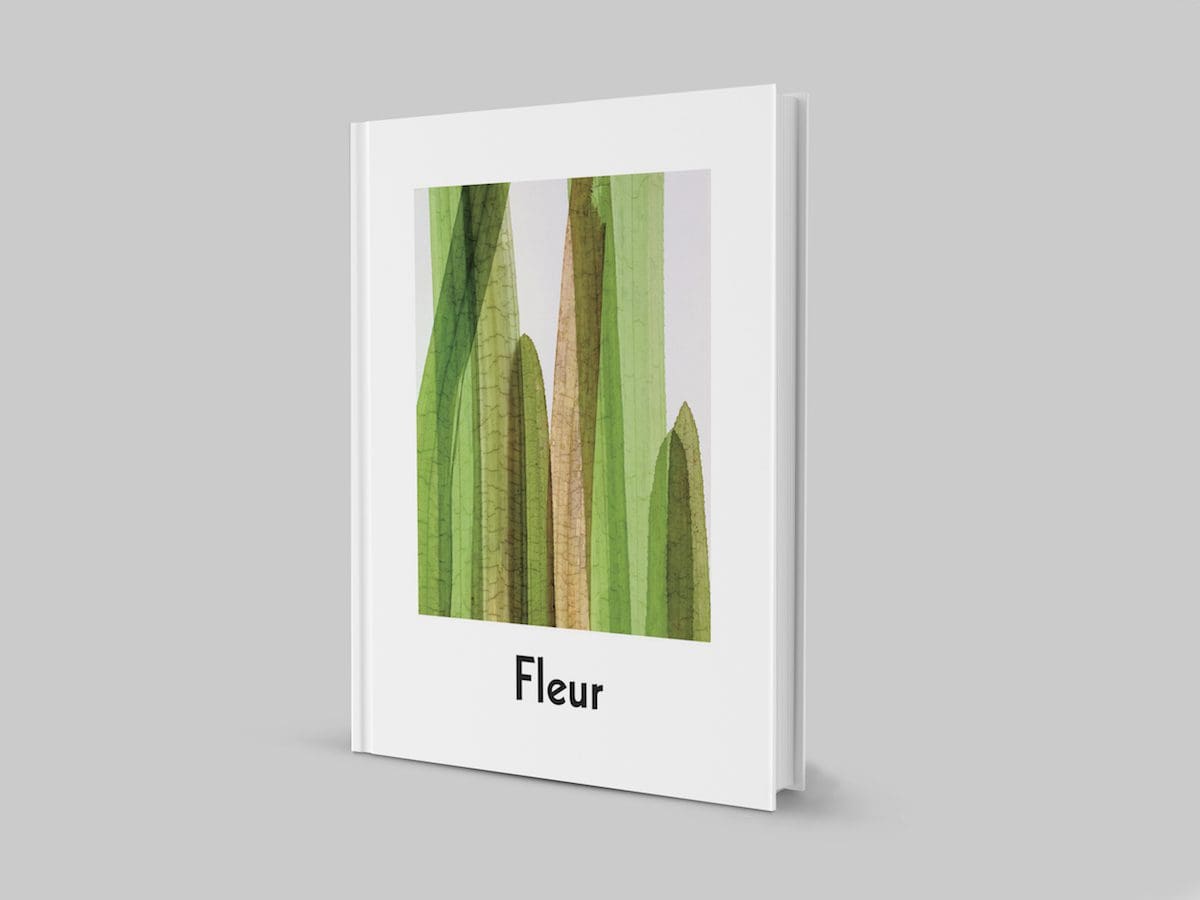

My monograph Fleur: Plant Portraits by Fleur Olby with a foreword by Wayne Ford, was published by FUEL Publishing in 2005, a combination of commissioned and personal work from ten years of floral still life. It was in the Tate Modern and The Photographers’ Gallery bookshops and distributed internationally with DAP and Thames and Hudson.

But after 2008 with two client insolvencies causing further problems after the financial crash, it took me a long time to find a way forward with my archives. The two commissions, Horsetail Equisetum for Gollifer Langston Architects and a textile collaboration with Woven Image in Australia were the archival commissions from that time that enabled me to move forward.

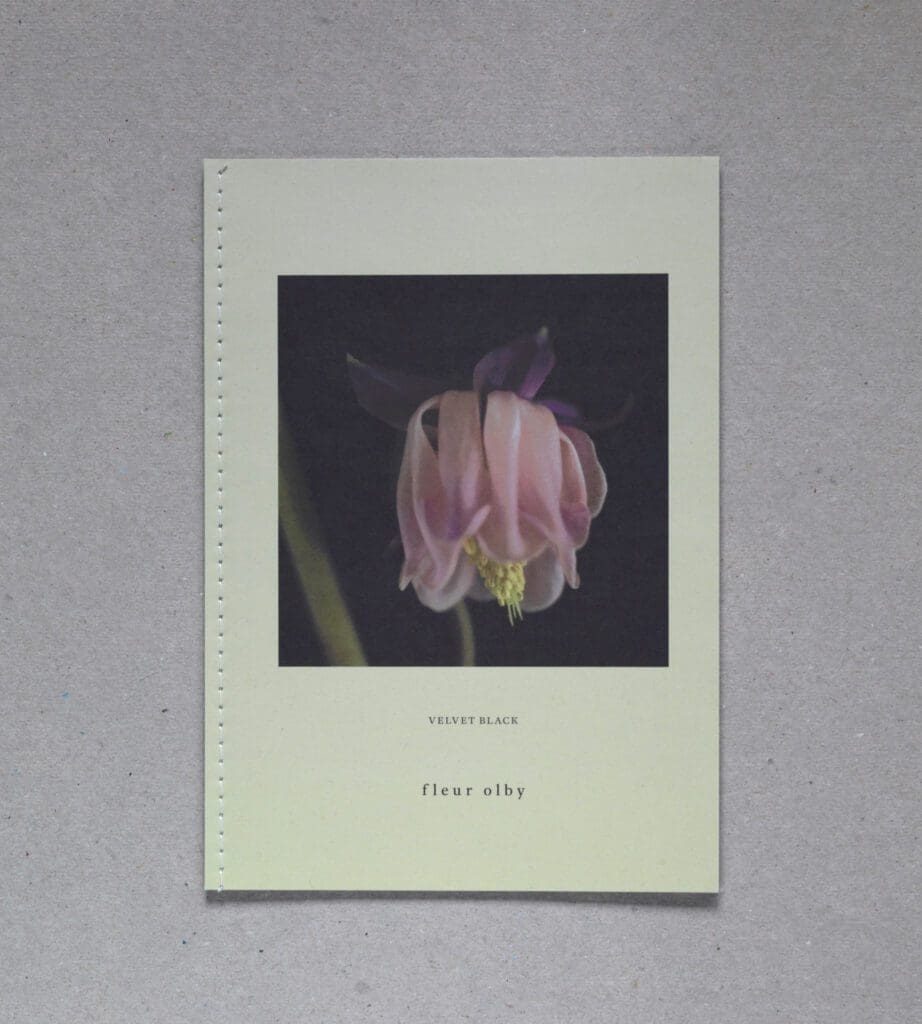

I had started a long-term project about the connection with Nature, Colour from Black. My Imprint has the first publication from these series, Velvet Black and limited edition prints that have exhibited at the Photography Gallery in the Museum of Gdansk and my solo show earlier this year at The Garden Museum, London. The A5 publication launched at Impressions Gallery Photobook Fair in Bradford and the A5 and A6 special edition are currently also at The Photographers’ Gallery bookshop in London. I aim to continue with self-publishing the series in small books and work in collaboration on the projects that evolve from them. Images from other series have also been shown in group shows in the UK and abroad.

Can you describe your process, and how your choice of film stocks, different formats and use of low light levels create the particular viewpoint you are interested in capturing?

The series artistic aim is to connect dreams and reality and through this work I have experimented with different mediums. It is less about the impact of a single image, my interest is in the pace and change of the narrative. The personal aim is to conserve plants and the elemental feeling of beauty in Nature. My commercial work was studio light, mostly shot on 5/4 Velvia and Provia film.

In my long-term series, the colour is subtle but fully saturated, in natural light. The low light started with the series Velvet Black as a present-day ode back to Victorian plant theatricals, collections and plants from a garden – the correlation between the transience of daylight and blooms.

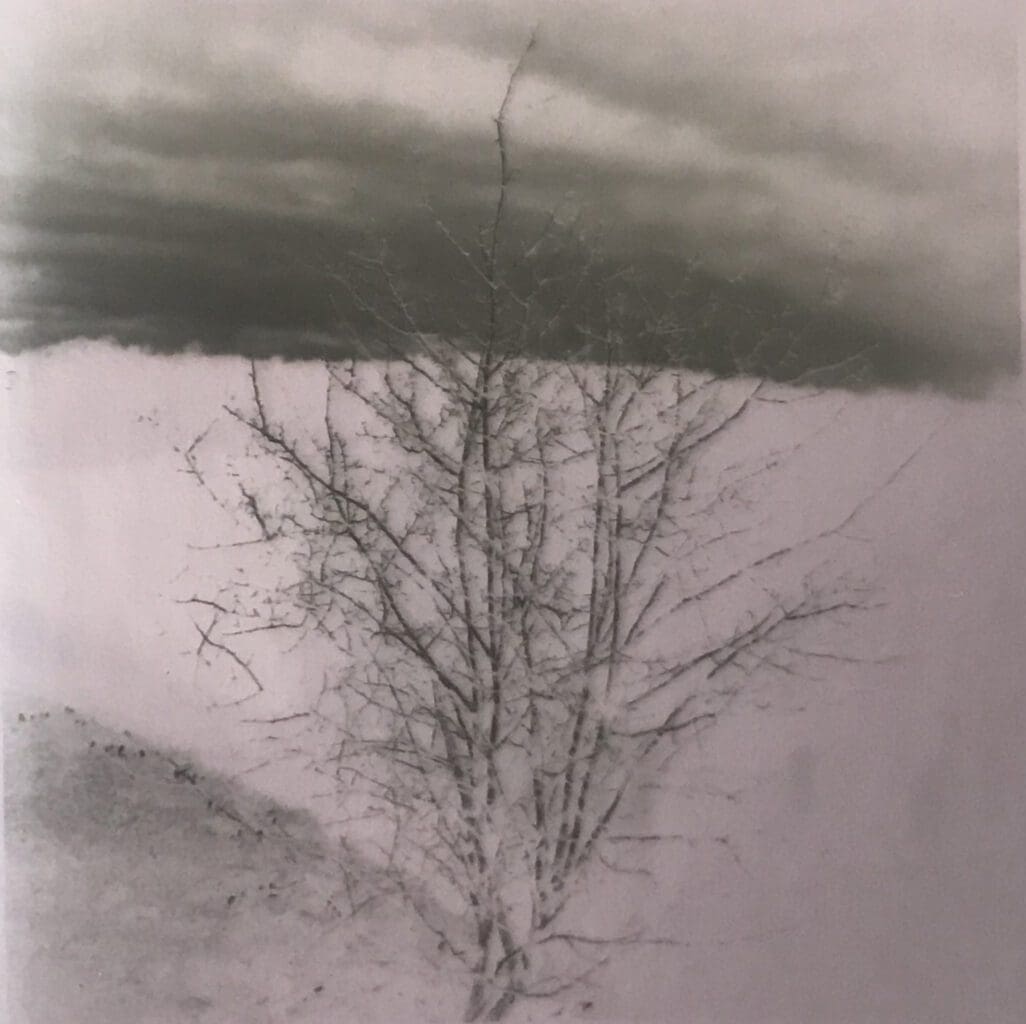

I was also experimenting with my iPhone as I was trying to capture the spontaneity of feeling from walking. My working process has evolved: It begins with walking and pictures that I revisit on medium format for a different kind of precision that allows long exposure. I am now mixing instant images and film from Black and white and colour. The series made at Hillside was the first time I combined the different mediums and shot Dusk, Dawn, Dusk in succession. I used Instax and my phone to find viewpoints from the paths. I remade some of the images on the Ipad to map out the plan.

Then I shot with a Polaroid camera in reasonable light and shot film and digital on medium format at Dusk and Dawn. The film was mostly Ilford, HP5, FP4 and XP2.

There is a quiet intensity to all of your work, a feeling of being tuned in to a different way of seeing the familiar. The fact that you work in series also gives a very strong narrative quality to your images. What would you like us to see in them?

Thank you, that means a lot to me! The quiet intensity was what I needed to reconnect with when I began to revisit childhood places that inspire me on the moors, on the hills, in the garden.

With the narratives about Nature, I wanted to slow down the viewing process and to question the feeling of Beauty through light and repetition within the series. In the book Velvet Black I use the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper and the folded pages to slow down the process in a similar way to a flower press. And the printed absorptance of the page makes the transient process of nature into a permanent object.

There is a distinct balance in your work between wild, elemental landscape and the intimacy and perfection of a single cut flower. What is the relationship between these two worlds for you?

I think this is the path I am trying to narrate between the perfect oak leaf from my childhood to the tree out on the hills.

When we asked you to come and take photographs at Hillside what were your first thoughts ? When you were here were there any particular observations you made about photographing a garden set in landscape?

It was great to hear from you both. I was excited about the thought of visiting Hillside. I remember our conversations about the work you were inviting artists to make and what aspects of the garden they were focusing on. But on arriving I couldn’t think how to divide it up into one particular interest and I knew I wanted to convey feeling.

I arrived between the storms of February, the quiet calm lull in the garden was breathtakingly beautiful. No-one was there until later today.

I started to walk – the paths led me everywhere. Enclosed and defined by the garden in and out of the landscape. I did not know this terrain, the feeling and scale are different, the quiet remains the same – the shape of the hill on the left is gentle and round, it stretches out into another at the front with incredible mature trees. The main garden is perched high up within the undulation of the hills. How will I capture this?

I felt I was intruding the serenity of the place, I stood amongst the plants’ skeletons taller than me and thanked them for remaining standing despite the storm – looked out at the echo of the trees beyond, walked down the hill towards them and looked back up to where I’d been standing – It is like a painting, brushstrokes of layered texture highlighted by the time of the year and the trees and hedges beyond it, darker shapes in repetition above. Light in colour as its ready to be cut for new planting and the two gates take me in and out of place and garden and into wonderment. I’m not sure I can express this.

Then there’s the bridge at the bottom of the stream with wrapped up plants on the edge that I could spend all day shooting, the vegetable garden! The artichokes! The Cavolo Nero – The two architectural stone troughs define the scale of the outdoor space and feel spiritual, a verbascum ode nearby reminds me of my Dad and makes me smile, the hedges, the orchards and the young woodland at the back. Flowers resiliently here and there touched me – intricate planting inspired me. I had to process a plan and start.

I wanted to try and capture this movement, the feelings from walking this dreamworld and its reality. I worked on different cameras in repetition in positive and negative to intensify the shapes and colour and black and white to intensify the feeling and pictorially play with resonance.

Do you feel that you learnt anything new from the time you spent photographing here?

It was immensely helpful to be invited to work like this, and I enjoyed the intensity of making the work. I made a new working process shooting 3 formats and running between captures to put the instant film to process inside and continue with the film outside. I made quite a lot of work in the time and it was the first time I shot constantly connecting dusk and dawn.

It enabled me to see how my work has progressed more clearly and how I can put it together because it was the perfect balance of how the garden and landscape coexist.

How was lockdown for you creatively?

Lockdown happened during my show at The Garden Museum.

I contributed to Quarantine Herbarium’s cyanotype project and the Trace Charity Print Sale which raised money for the charities Crisis and Refuge.

I listened more to the birds, watched the animals’ paths and felt exceptionally close to them and that continues. I was also busy shielding family, and I spent more time growing vegetables which I do as much as possible.

I stopped shooting and started to edit more.

What are you working on now and can you share any ideas you have for future projects?

I have had to revise my plans for this year, events I had committed to were cancelled. I am reworking everything and plan to bring the next series out in 2021.

The full edit of the photographs Fleur took can be seen on her website.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Portrait: Howard Sooley

All other photographs: Fleur Olby

Published 24 October 2020

Huw Morgan | 28 February 2020

When we last saw each other in October Flora and I had planned on her returning to Hillside in the very depths of winter to see what she could create with the skeletons of last year’s growth when there was hardly a flower to be seen in the garden. We pencilled in a late January date in the diary. However, I was taken ill after Christmas and was out of action until early February. This meant that the next available date for us to meet was at the end of last week, when the season was definitely starting to tip into spring.

Flora arrived on Thursday evening with her good friend Paul, who gardens with her at Westhill Farm. He has assisted Flora on the last two shoots here, cutting and conditioning flowers, organising and filling containers and clearing up afterwards, not to mention the laughter and banter. We could not have done any of them without his help. We were all up early on Friday morning, wary of the weather forecast with its warnings of another approaching storm. I had gathered some woody material – hazel, willow and cherry plum – from the hedgerows, woods and garden the previous day, and there was a wide selection of dead material in the tractor barn that I had saved from the garden before Christmas. After breakfast Flora and Paul took a tour of the garden to select the things that took their fancy to bring colour and a feeling of hope to the arrangement.

With storm clouds gathering and wind gusting erratically, and despite the fact that we had decided to make the arrangement under cover, the weather conditions were challenging. On more than one occasion the entire, and nearly completed, arrangement almost blew over. Fortunately Paul was quick off the mark and managed to catch it, preventing it from needing to be entirely remade. Just moments after I had taken the last shot of the finished arrangement a great easterly gust blew into the barn and sent everything flying. We all laughed and understood that the shoot was well and truly over.

Although it was testing working and photographing in these conditions it felt like a very authentic engagement with and recording of the reality of the season.

Flora Starkey | 28 February 2020

It is winter at Hillside and there’s a new quieter beauty in the garden. Again, I’m happy to be here on the cusp of the season as spring starts to show beneath the fallen grasses and branches that are bare of leaves.

The rains held off for a few hours on Friday morning, but the winds still blew. Huw and I decided it would be impossible to try and continue our series in front of our usual rusted barn background so we moved behind and into the inside corner of the barn. We both liked the light there and hoped we’d be more sheltered from the elements, but there were still times the wind caught us from the side – all adding to the fun.

I’d used ceramic and glass vessels in the summer and autumn arrangements and so this time I was drawn to the idea of metal. Specifically vases made from old mortar shell casings. I brought a small collection with me, including a bowl with a drilled lid gifted to me by my friend Paul. A remnant of World War 1 and life in the trenches. I like the idea of using flowers to reflect, remember and bring beauty from the darkness. I guess it seemed especially fitting for the season with the violets and primroses showing up and braving the end of winter.

Despite the fact that much of the garden was dormant, Huw cut some beautiful single flowering Prunus from the border hedgerows. These, along with hanging hazel lambs’ tails and a few varieties of silvery, soft catkins formed the base of the shape. I especially loved the snowy delicacy of the Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’.

Some tall but delicate stems of rosemary and a twist of honeysuckle coming into leaf added some essential green. These were followed pretty quickly by a frame of dried beauties that Huw had saved for me last autumn – some wonderful silver stars of aster and rusty licorice seedheads. It has been interesting for me to recognise how important the dried elements from the season before have felt every time I’ve come here.

With the taller elements in place, I moved to the flowers below the canopy – a single snip from several varieties of hellebore including a double black that I was particularly taken with. With the winds picking up again, it was time to focus on my favourite low lidded vase at the front. This held a tiny carpet of primroses, snowdrops, Cyclamen coum and a violet complete with leaves.

I had wondered how much of a challenge our winter arrangement would be. It might be that it’s my favourite yet.

Asclepias tuberosa

Cardamine quinquefolia

Corylus avellana

Cyclamen coum

Epimedium x versicolor ‘Sulphureum’

Eurybia x herveyi

Galanthus elwesii ‘Cedric’s Prolific’

Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’

Glycyrrhiza yunnanensis

Helleborus hybridus Double black

Helleborus hybridus Single black

Helleborus hybridus Single Dark Pink Spotted

Helleborus hybridus Single Green Picotee Shades Dark Nectaries

Helleborus hybridus Single white dark nectaries

Helleborus hybridus Single yellow spotted dark nectaries

Lonicera periclymenum ‘Graham Thomas’

Primula vulgaris

Prunus cerasifera

Quercus robur

Rosmarinus officinalis

Salix gracilistyla

Salix purpurea ‘Nancy Saunders’

Teucrium hircanicum ‘Paradise Delight’

Verbascum phoenicium ‘Violetta’

Viola odorata

Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 28 February 2020

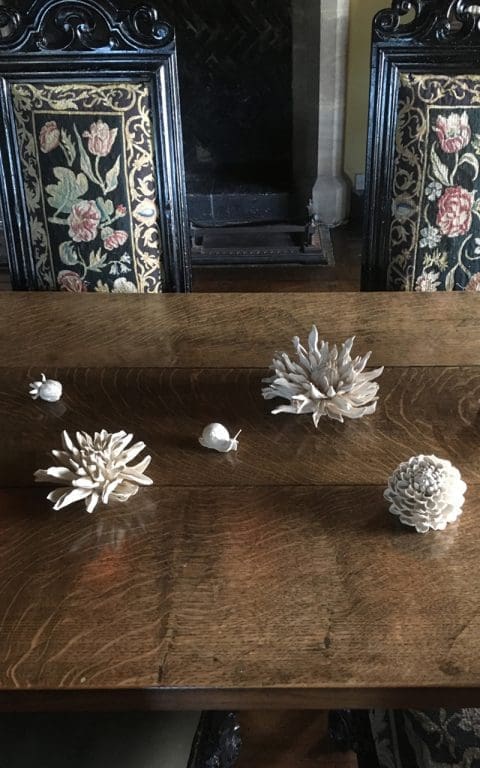

Kaori Tatebayashi is a Japanese ceramicist living and working in London. She comes from a family of ceramics traders, and was surrounded by traditional Japanese ceramics from an early age. After gaining an MA in Ceramics from Kyoto City University of Art, in 1995 she came to London on an exchange programme to study at the Royal College of Art. Kaori makes both sculpture and tableware, but it is her sculptural pieces, which are inspired by plants and nature, which I was interested to find out more about.

Kaori, you have a longstanding family relationship with ceramics. Can you tell me about this and how it influenced your development as a ceramicist ?

I was born in Arita in Japan, a little village renowned for Arita porcelain, which in Europe is known as Old Imari. My grandfather was an Arita-ware merchant and took orders from hotels and restaurants from all over Japan. The scene of my family gathering together to pack tableware commissioned from various potteries in the village in navy blue paper with our family company logo remain vividly in my memory as a fun event.

Each May, we participated in a pottery festival in Arita. My cousins and I were allowed to sell little porcelain figurines next to adults selling tableware and, when we sold the figurines, we were treated with too many ice creams by visiting relatives. In 2016 Arita celebrated 400 years of porcelain production. Although I don’t work in porcelain, ceramic is definitely in my blood.

You studied ceramics both in Japan and then in London. Can you tell me about the key things that you learnt in each place ?

In Japan, we were taught as if you were apprenticed to a master potter, learning everything from traditional spiral wedging, which they say will take 3 years to master, to throwing and hand-building techniques to firing electric, oil, gas and wood fired kilns. By the time you graduate from university, you have learnt everything you need to know to run your own ceramic workshop. It was about skill-based making at BA level then, for the MA, you focussed on how to express yourself in clay and with the range of ceramic material.

During my exchange at the Royal College of Art and a short residency in Denmark, I was liberated from all of the rules and restrictions and the traditional approaches towards clay and glazes I had blindly been studying in Japan and my work changed dramatically, especially the finish.

In order to make what I do now, I needed all the skills I gained from the training I had in my university years in Japan as well as the freeing of my mind which I got from studying in the U.K.

Why did you decide to stay in London to continue your ceramic practice after finishing your studies ? What did the city offer you that Kyoto didn’t ?

After my exchange at the RCA, I went back to Kyoto to finish my MA then lived in Tokyo for over 4 years mainly teaching, but I didn’t enjoy my life there. I missed being close to nature and couldn’t find my place in Tokyo which was too fast, too vast, and I felt the life there had no sense of the seasons. I moved back to the U.K. in 2001 and have stayed here ever since. People are surprised when I say London is full of green and that life here is much calmer than in Tokyo, but it’s true. I don’t feel the urge to be near nature in London as I did in Tokyo.

Also I choose to live and work in the U.K. because my sculptural work was better received here than in Japan, which was still very much stuck in tradition then.

You started making ceramic sculptures of inanimate objects, especially clothing. What was your impetus for making these pieces ?

Individual objects were my early pieces. At that stage, I was curious about how far I could push the material and challenge my skill. Also, my focus was on memory. The clay’s ability to capture time and its elusive existence, simultaneously having both fragility and permanence, overlapped with my ideas about memory. I was making old-fashioned, everyday objects which encouraged people’s memories and played with the sense of time being stopped.

I started making sculpture in my university days, and it was the reason I came to study at the RCA. Ceramic sculpture didn’t have a place in the world of traditional Japanese ceramics. Making tableware came after graduating with my MA, when I was teaching full time. My short periods of free time only allowed me to make small, repetitive pieces and so was most suitable for making tableware, which also came naturally to me due to my family background.

Can you explain the development of your work from the replicas of single items of clothing to the more formal tableau installations of multiple pieces which included a wide range of different subjects ?

My focus was on the challenge of replicating each item. In a way, I was training myself, developing my skills further. You could see them as my studies. Once I had mastered the required skills, I started to create still life series, much as you would do with drawings.

Where did your most recent and current interest in plants, flowers, fruits and vegetables (and insects and animals) originate and what is the link between these pieces and your earlier work ?

My passion for gardening started influencing my work gradually, but even in a much earlier stage of my life, my grandfather who collected and named some wild orchids from his local mountain, must have seeded something in me as well. My very first flower piece appeared in 2005, which I made for Ceramic Art London held at the RCA (it has now moved to Central St. Martin’s). It was a single rose stem, forgotten and dying in a vase. A moment preserved in ceramic, which later became my main theme. In the true sense, I am not trying to preserve plants, but time itself. By preserving plants, which have a very short life, you get the sense of time being captured and permanently frozen. I often add insects and other creatures, especially snails which, although they have movement, it is very slow, in order to enhance this sense of time being stopped.

Can you tell me about your working process ? How do you make your flower pieces ?

I usually work by going straight into modelling in stoneware clay, observing real flowers and plants from 360 degrees. I quickly calculate what method is most suitable to use, which part I should make first, the drying time and which is the best forming technique to use. I have been working in clay for nearly 30 years now. By looking at object, I can immediately tell if the object is at all possible to make and how to achieve the form.

The tools I use are very simple, my hands and a knife which I made myself. If it is a flower, I make it petal by petal, no secret or magic involved!

The pieces must be dried slowly, then fired straight to 1250°C without a bisque firing.

Can you tell me about the Banquet pieces and the work that you created for your exhibition at Forde Abbey ?

The Banquet is one of my largest installations. It was developed from my small still life series and I wanted to create a large flamboyant scenery based on the feel of the Dutch Old Master painting.

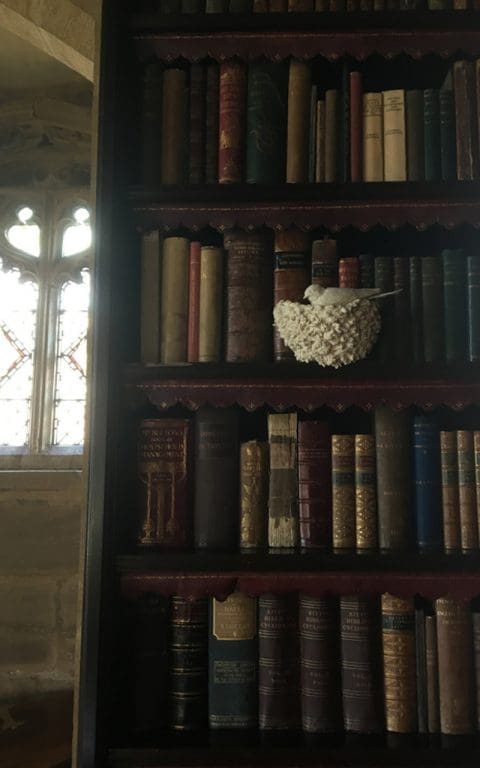

The work exhibited at Forde Abbey was my first site specific installation, which I created in my studio after a week’s residency there. To correspond to the feeling of the 900 year old library and the beautiful gardens and nature there, and because the exhibition was held in September, I created dahlias which I scattered down the central table, pumpkins (the originals of which had been grown in their kitchen garden) peeping from between the old books and swallows nesting in front of the book shelves. I wanted a fairy tale aspect and a slight spookiness, but not too conceptual so that visitors could really enjoy the experience.

What was the inspiration for the black stoneware pieces, Lunar Eclipse and Night Garden, Delft and the pale stoneware Paradiso di Flora?

Again, I was inspired by Dutch Master paintings.

At Ceramic Art London, I designed my stand to show the pieces, one side in black and the other side in white clay, the mirror image of the same object in black and white.

Black clay has a totally different feel to the white. Mysterious, dark and somewhat more intriguing. I want to experiment more with black clay in the future.

What are you working on the moment and are there any plants that you are particularly interested in working with and why ?

I am working on the pieces for my solo show in Tokyo happening at the same time as the Olympics next year. And from Spring onwards, I will be working on botanical pieces for my solo show at Tristan Hoare Gallery in London in November 2020.

I have been studying the school of Japanese old masters known as Rimpa which started developing from 15th century onwards, reaching a peak in the 17th century. Japanese paintings in general are very seasonal and plants and flowers are often the most significant subject of their paintings. I am interested in creating a British version of them with wild flowers and plants native to this country or popular cultivars from that particular era, perhaps.

Interview: Huw Morgan | Studio photographs: Huw Morgan | All other photographs: Kaori Tatebayashi

Published 14 December 2019

Huw Morgan | 31 October 2019

It is almost three months since Flora first came to Hillside to work with material taken from the garden here. That summer visit was an introductory and learning experience for us both. Flora’s first time in the garden here, time needed to get to know the garden, time to find a setting to shoot in, the challenges of working outside and to be photographed in process when she is usually unseen, off stage. For me there was the self-imposed pressure to do Flora’s art justice in my photographs and to capture those moments of consideration, reflection, decisiveness, choice, care, which I was witness to as she worked.

As she worked this time I started to notice the ways in which Flora relates physically to the space in which the flower arrangement was being made. Standing with her back to me I could tell that she was judging, evaluating, balancing, deciding, framing, all of which could be read from the set of her jaw or the angle of a shoulder. The delicacy with which she would select a stem, find a location for it, and then gently and firmly aid and guide it into position. The final stroking of the plant to allow it to fall naturally and also the sensual pleasure of engaging with plants this intimately.

It reminded me of something Midori, the head gardener at Tokachi Millennium Forest said to us when she was staying here early last autumn, which is that the last flower arrangements of the year should be relished as they are the last opportunity for ‘touching green’ before the winter comes.

Flora Starkey | 1 November 2019

The last time I came to Hillside, Summer was making way for Autumn. This visit Autumn is peaking and the gardens are more subdued, but no less splendid.

We decided to shoot in the same location as before, in front of the beautifully rusted corrugated iron barn. I’m interested to see how the four images will sit together by the end of the year and like the idea of them being in the same place.

As before, we cut sparingly – no more than a few stems from each plant. This time I chose a lot of dried structure – dill, red orache, fluffy willow herb and a stem of Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’ with its delicate mottled yellow leaves. And of course, some essential autumnal colour in the form of Euphorbia cornigera and a snipping from the fiery Prunus x yedoensis.

Moving back to the barn, we pick some blue glass jars from the house & get to work. The space will always dictate the arrangement in terms of scale and the zinc table outside calls for size, not least because of the October wind.

The tall dried pieces were placed first creating the framework, a beautiful Aster umbellatus towering over the others. A few leaves of royal fern quickly followed, adding a myriad of colours in each stem. I carried on building the colour with warm tones before offsetting with the deep blues and violets of a few varieties of salvia.

Even though the stems keep get buffeted by the wind and moving around, I like this way of working. It’s spontaneous & can’t be too precious. After a while, I feel like we’re missing some pops of brighter colour and go foraging for rosehips, finding some spindleberry on the way.

As these are more structural branches, I end up taking the arrangement apart & starting again, adding these elements earlier. Some of the salvia had also started to wilt by the time we got back so we cut a little more. If I were to use this again, I’d try & sear it to make it last longer. I finish with a curling tail of yellow amsonia, a shock of pale yellow scabious and some shiny black berries of wild privet.

As well as wanting to represent the garden in all her autumnal glory, I was also keen to make a smaller and simpler arrangement – something quieter that allows the stems their space to shine. It’s probably how I’m happiest working.

The picture window outside the milking barn provides the setting and frames the vases with the changing landscape behind. I start with a length of old man’s beard and some more euphorbia. A few stems of panicum & chasmanthium add height along with a speckled toad lily. A sprinkling of dainty white asters were added lower down and some oxblood red leaves of fagopyrum trail off to the side, slightly broken but more beautiful for it.

Back in the garden & you can see the silhouettes of winter beginning to appear. Huw & I spent a little time looking at the plants that we’d like to dry and preserve for our next shoot. I’m looking forward to the change of the season already

Anethum graveolens

Aster umbellatus

Astilbe rivularis

Atriplex hortensis

Cercidiphyllum japonicum

Chamaenerion angustifolium ‘Album’

Chasmanthium latifolium

Euonymus europaeus

Euphorbia cornigera

Ligustrum vulgare

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’

Osmunda regalis

Prunus x yedoensis

Rosa eglanteria

Salvia ‘Blue Enigma’

Salvia ‘Blue Note’

Salvia uliginosa

Sambucus nigra

Scabiosa ochroleuca

Thalictrum ‘White Splendide’

Thalictrum ‘

Aster unnamed white

Chasmanthium latifolium

Clematis vitalba

Euphorbia cornigera

Fagopyrum dibotrys

Oenothera stricta ‘Sulphurea’

Panicum virgatum ‘Heiliger Hain’

Papaver rupifragum

Rosa ‘The Lady of Shallot’

Salvia uliginosa

Tricyrtis formosana ‘Dark Beauty’

Tropaeolum majus ‘Mahogany’

Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 3 November 2019

Huw Morgan | 15 August 2019

Although I already knew of her by name, reputation and Instagram it was at the 2015 Port Eliot Festival, where we were both judges for the Flower Show, that I first met Flora Starkey. We hit it off instantly, finding that we gravitated towards the same entries in each of the show classes; those where the immediacy, spirit and freedom of the arrangement was more important than technical proficiency, complexity or sophistication.

These are some of the very qualities that set Flora’s work apart and she is rightly feted for her lightness of touch, very particular use of colour and sensitivity to decay and the use of the ephemeral in her arrangements, which have a melancholy beauty and Late Romantic sensibility. Amongst the new generation of floral artists hers is a completely distinctive vision.

I knew immediately that it would be exciting to give Flora the opportunity to come to Hillside and see what she made of our selection of plants and flowers. Although it has taken several years to come to fruition, finally last week Flora came.

After a walk around the garden taking everything in (and impressing me with her plant knowledge) Flora identified the things she most wanted to use. It was wonderful to see her working with such intent focus and speed. The instinctive way in which she both selected plants from the garden and then placed them together in the arrangements was both very down to earth and practical, but also full of the mystery of intuitive artistic expression.

Over a glass of wine after an adrenalin charged afternoon, I asked Flora if she would like to come back to see the garden in another season. ‘Of course !’, she said. And so, schedules allowing, we are planning for Flora to return to make further floral portraits of the garden here in autumn, winter and spring.

Flora Starkey | 8 August 2019

On arriving at Hillside, it is immediately apparent how the land holds the house & outbuildings central amongst the different areas of garden, the fields and valley beyond. Sitting outside, while Huw made a pot of tea, I had a strong sense of the patchwork of history of the place and the different stories that have been woven there over time. There is magic in somewhere so loved.

We chose the location for the shots outside one of the original barns surrounded by the kitchen garden – a place of old & new. For me, the space is always the starting point of any arrangement and the corrugated metal backdrop with its patches of rust led to Huw’s collection of stoneware vases.

Then to the garden. I wanted to create an arrangement from this setting while impacting on it as little as possible, so we cut sparingly – one or two stems from each plant – some of which had already been blown over in the wind. I chose what I felt captured the feel of this time of year, high summer with autumnal undertones. I’m always drawn to the changing colour of the leaves as they move through the seasons, the most beautiful stems in my opinion are the ones in transition or decline.

I felt there were two stories in the flowers at Hillside in early August: firstly the creams and buttery yellows with the odd splash of blue & lavender, and then the drama and heat of the reds, dark purples and browns. So we decided on two arrangements. I wanted to show the flowers for what they are: wild and changing, not too ‘arranged’, and of their place. Using a collection of mixed sized vases to make one piece is a way that I often like to work as it allows for a fairly large arrangement whilst giving more space in between the stems.

The molopospermum led the first with its sculptural leaves of bright yellow turning rust brown, and then a tall stem of Achillea chrysocoma ‘Grandiflora’, dried and curled at the top. Further down the stem, the leaves became a rainbow mix of pale green fused with yellow and wine red.

Evening primrose, fennel, actaea and Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’ followed to give height and structure and all in different stages between flower & seed. This is where I find the true beauty, in the changes through which every plant evolves. Then a single stem of Rose ‘The Lark Ascending’, to add a touch of glamour, quickly offset with some bone coloured poppy heads. A hemerocallis lily was softened by some chasmanthium and two varieties of Calamintha in cream and lavender to visually draw the stems together. Finally some echinops and a sprig of Eryngium giganteum snipped from under the table to finish.

The second arrangement featured pops of bright red in the dahlias, crocosmia and geranium against a tangled backdrop of daucus, verbena, sanguisorba, persicaria and asters with a single arching stem of dierama in seed swinging above. Again, it was the mottled & turning leaves of the Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’ with its dried flower heads that brought the most joy.

This really must be the most satisfying kind of creativity: working with flowers in your direct locality & the opportunity to use so-called imperfect stems, the beauty in which is so often strangely overlooked.

Achillea chrysocoma ‘Grandiflora’

Actaea racemosa

Bupleurum falcatum

Bupleurum longifolium ‘Bronze Beauty’

Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta ‘Blue Cloud’

Calamintha sylvatica ‘Menthe’

Chasmanthium latifolium

Echinops bannaticus ‘Veitch’s Blue’

Eryngium giganteum

Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’

Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca

Molopospermum peloponnesiacum

Oenothera stricta ‘Sulphurea’

Papaver somniferum ‘Single Black’

Rosa ‘The Lark Ascending’

Cephalaria transylvanica

Cirsium canum

Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’

Dahlia ‘Verrone’s Obsidian’

Dahlia coccinea ‘Dixter Strain’

Dahlia species (‘Talfourd Red’)

Daucus carota

Deschampsia cespitosa ‘Schottland’

Dierama pulcherrimum ‘Blackbird’

Eurybia divaricata ‘Beth’

Eurybia x herveyi

Lythrum virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’

Nepeta ‘Blue Dragon’

Origanum laevigatum ‘Herrenhausen’

Pelargonium ‘Stadt Bern’

Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’

Rosa spinosissima

Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’

Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’

Photographs | Huw Morgan

Published 17 August 2019

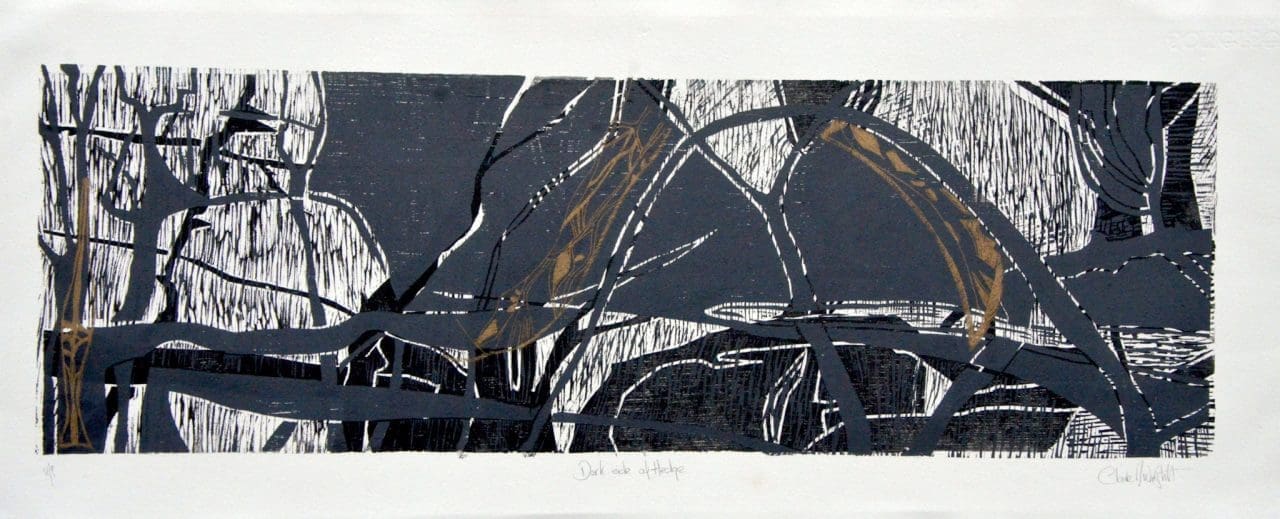

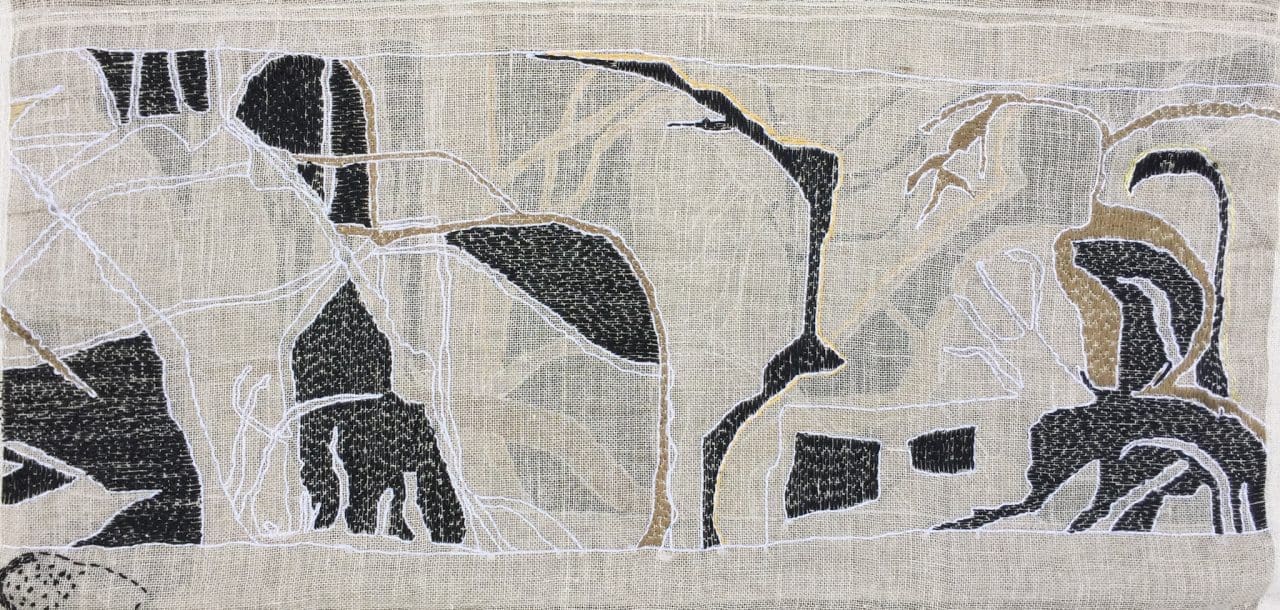

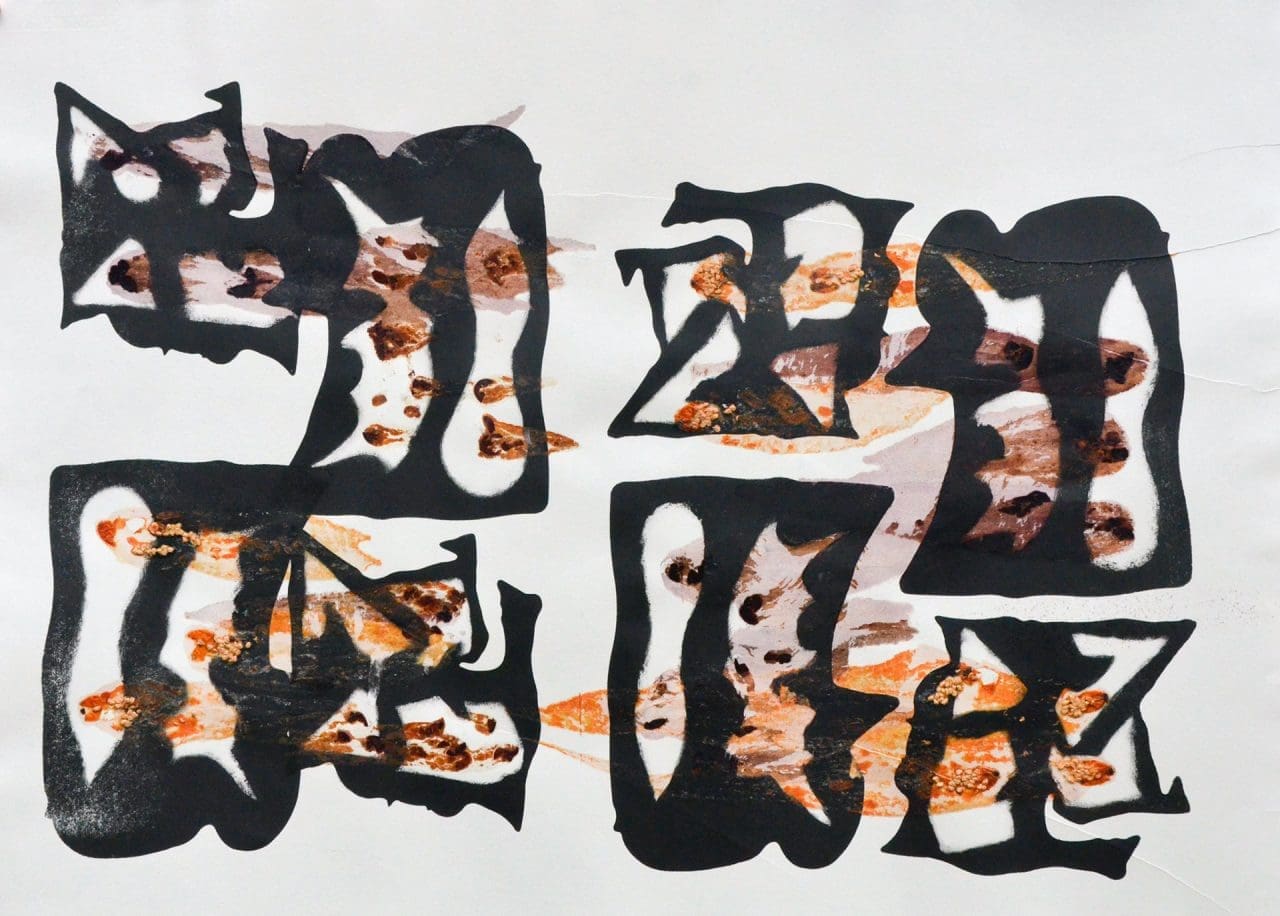

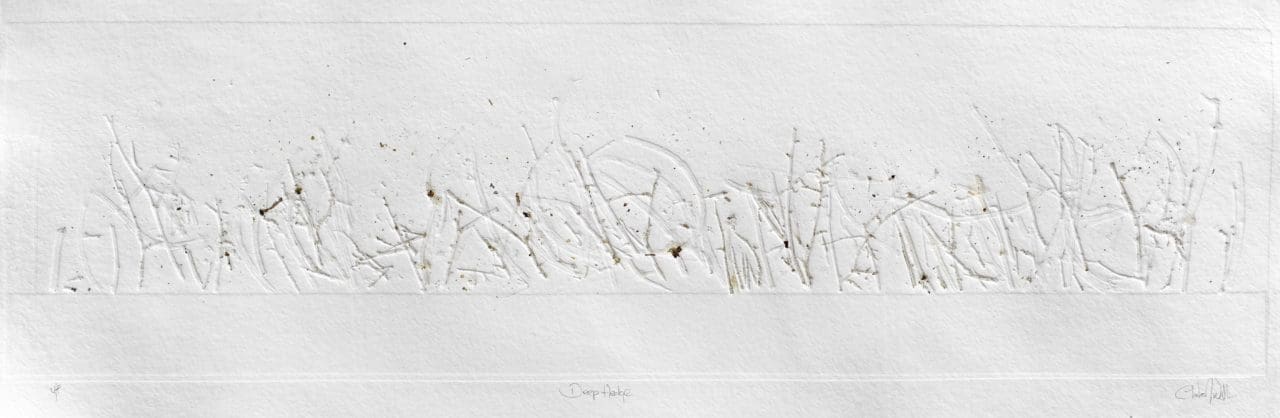

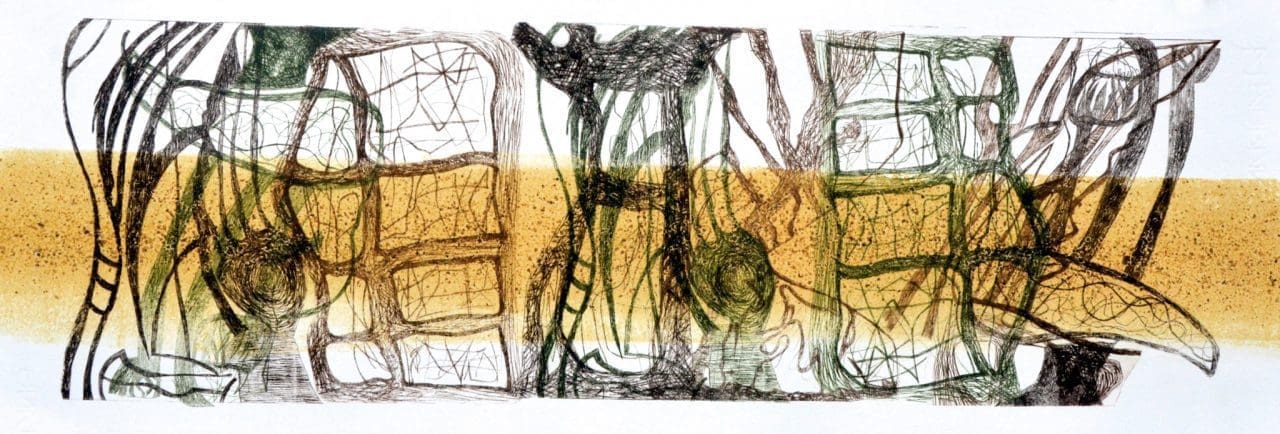

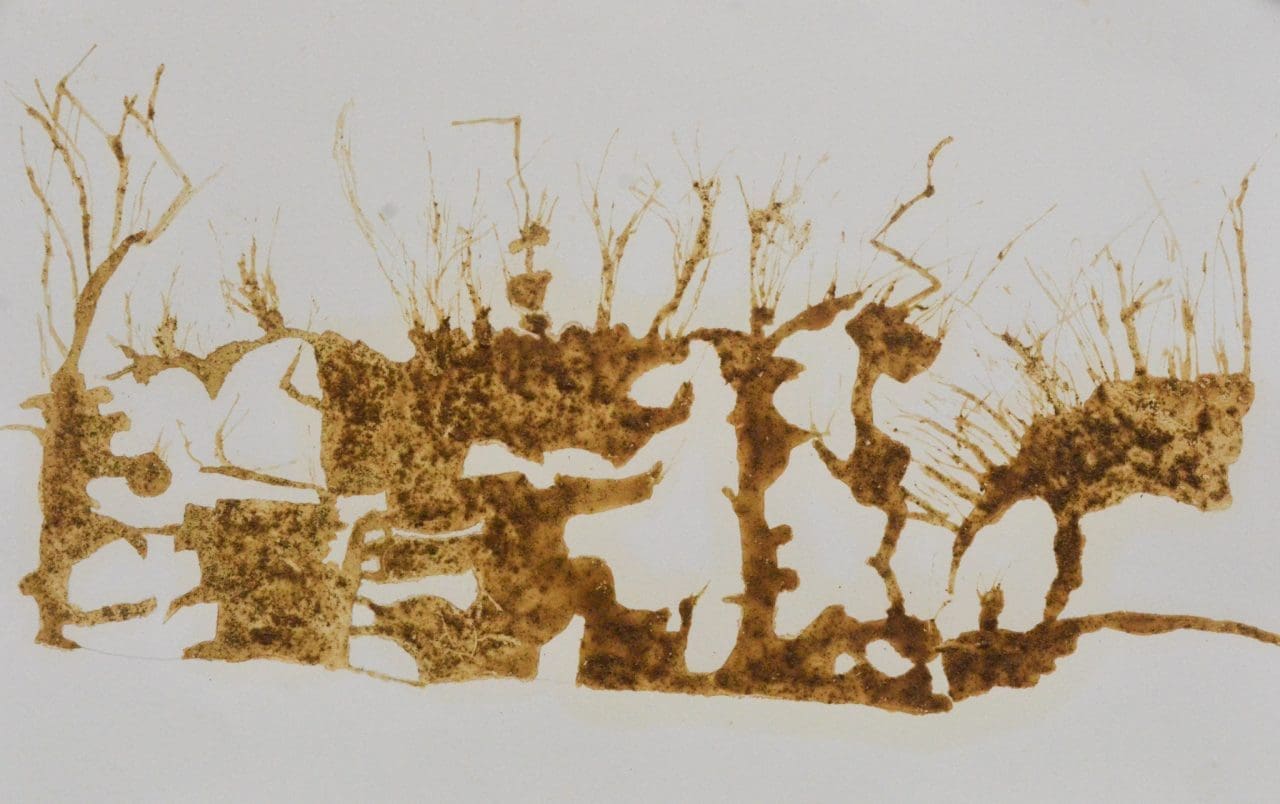

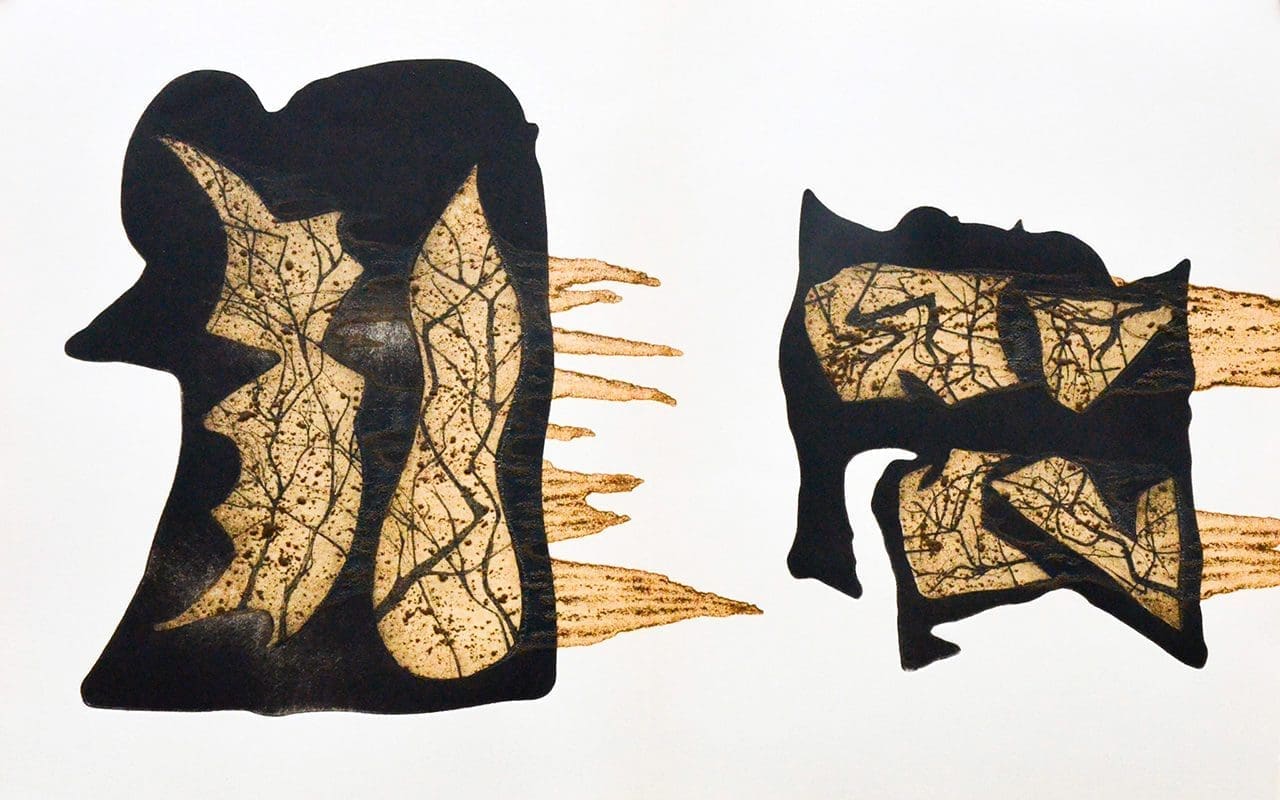

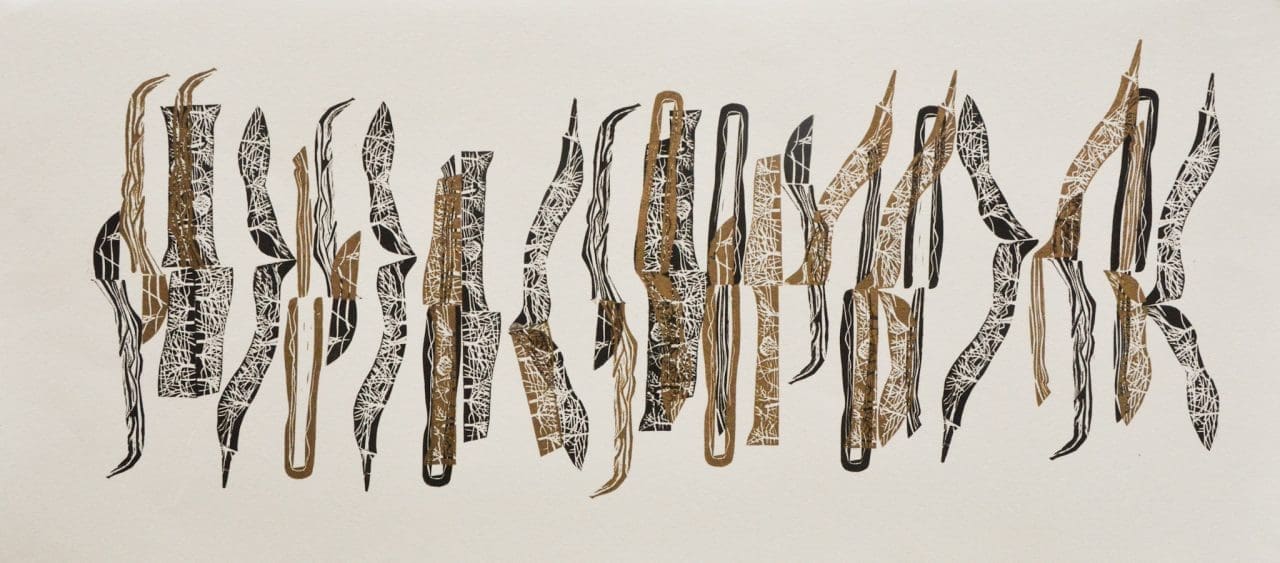

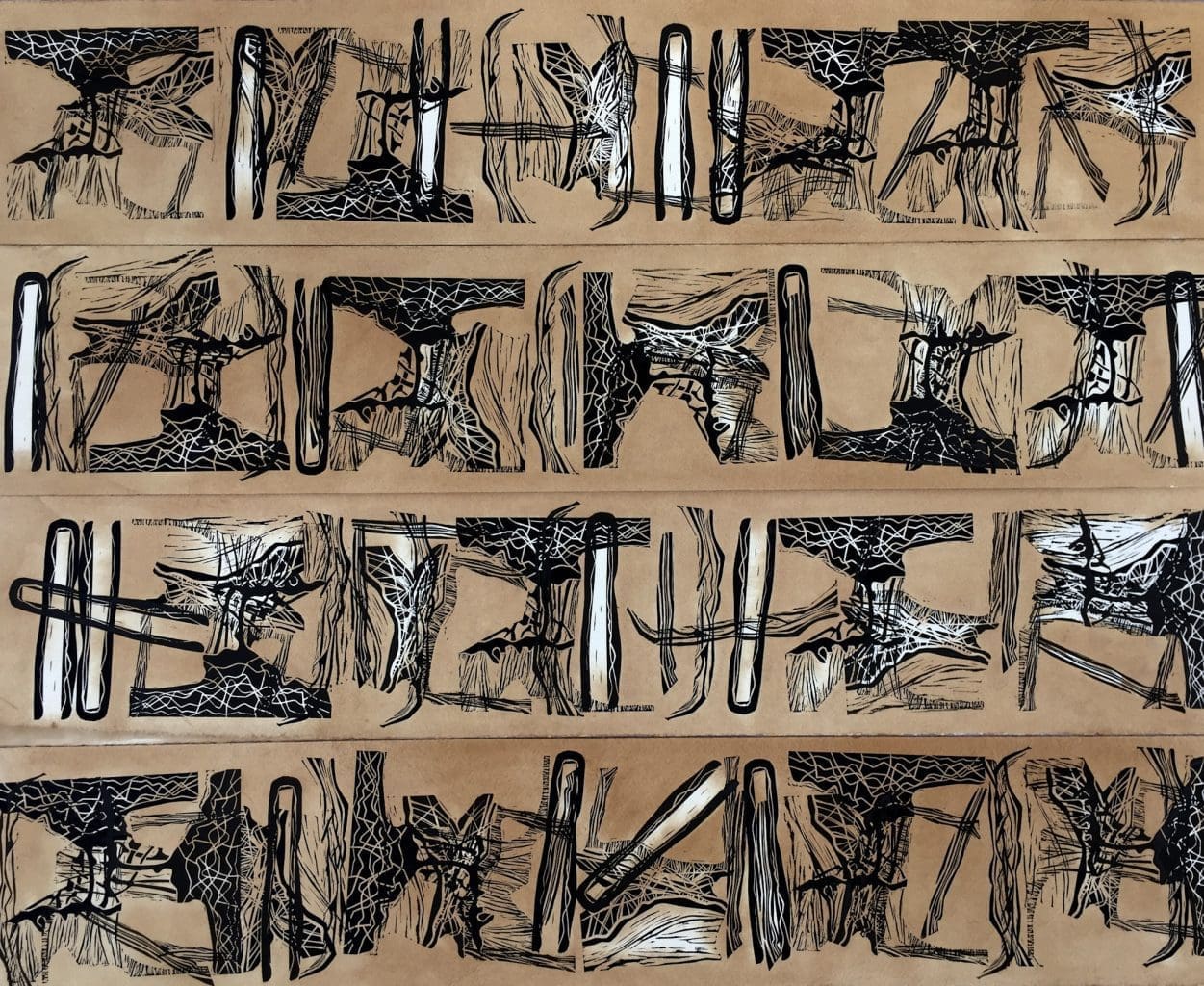

Claire Morris-Wright is an artist and printmaker working with lino and wood cut, etching, lithography, aquatint, embroidery, textile and other media. Last year she had a major show, The Hedge Project, which was the culmination of two years’ work, and which used a hedge near her home as the locus for examining a range of deeply felt, personal emotions.

So, Claire, why did you want to become an artist?

I’ve just always made things. As a kid I was always making things. So I’ve always been a maker, creative, and I was always encouraged in that. My parents used to take me and my brothers to art galleries and museums when I was young and I loved it.

As a child I was always drawing, making clothes for dolls, building dens with my brothers and creating little spaces. I was not particularly academic, but a good-at-making-clothes sort of girl. I always knew I wanted to go to art college, so that was what I aimed for.

My secondary school, Bishop Bright Grammar, was very progressive, where you designed your own timetable and all the teachers were really young and hippie – this was in the ‘70s – and we could do any subject we wanted; design, textiles, printmaking, ceramics. So I took ceramics O Level a year early with help from the Open University programmes that I watched in my spare time.

Then I went to Brighton Art College and studied Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics, specialising in ceramics and wood. Ceramics is my second love. I have a particular affinity with natural materials, the earthbound or anything connected to nature. That’s what moves me. My work has always been about land and landscape and what’s around me and how I navigate that emotionally.

In terms of how I work, I simply respond to things. I respond to natural environments on an intuitive and emotional level. I try to explore this through my practice and understand why I had that response and aim to imbue my work with that essence. My artistic process is completely rooted in the environment that I live in. Like Howard Hodgkin said, ‘There has to be some emotional content in it. There has to be a resonance about you and that place.’

How do you work?

I go to the Leicester Print Workshop to do the printmaking. It’s a fantastic workshop facility. I was involved in setting that up, a long time ago now. When I first moved to Leicester in 1980 I was part of a group of artists who set up a studio group called the Knighton Lane Studios. We wanted somewhere to print and so set up our own workshop, which was in a little terraced house to start with. It’s moved twice to its now existing space in a big purpose-built building. It’s all grown up now, which is great. However, I rely mostly on my table at home or the outdoors to make work. I don’t have a studio, but I believe that since I am the place where the creative thinking happens I can make and create wherever I can in my home.

Are you still involved in managing the printworks?

I stepped out of it before its first move, because I was working full-time in Nottingham at the Castle Museum, where I was the Visual Arts Education and Outreach Officer, developing interpretive work from the collection and contemporary exhibitions. I was responsible for getting school groups and community groups in to look at the art collections. We then had two children, so it was only when they were older that I had more time and returned to my practice and the print workshop.

So tell me about how the Hedge Project came about?

I had a few experiences that were deeply shocking and subsequently had a period of depression. During that time the hedge became very important psychologically and I found that I needed to go up to the hedge on a regular basis. I started to develop a relationship with the hedge knowing there was this pull to record these emotions creatively. I produced a large body of art work with Arts Council funding and sponsorship from the Oppenheim-John Downes Memorial Trust and Goldmark Art. I held three exhibitions of the art work, made films and have delivered community engagement workshops over the past six months.

What was the feeling that drew you up there?

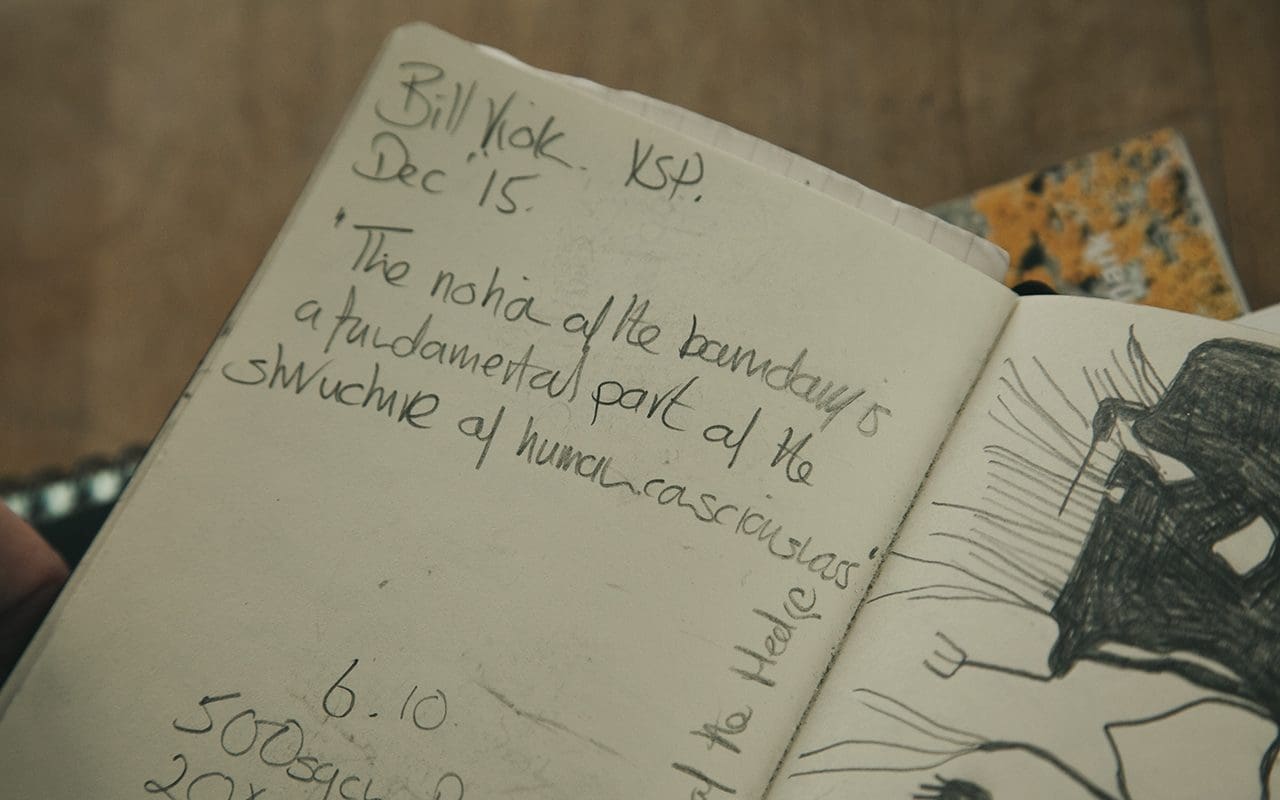

It was definitely quite powerful how I felt drawn to it. It was a beautiful structure in the landscape that was seasonally changing and I was changing at the same time. It is very prominent on the horizon and, because I walk around the village regularly, I just kept seeing it, so I started walking the length of it, looking at it, drawing and thinking about it. I did that every week for two years. Gradually my relationship with the hedge became deeper and started to take on more significance as a symbol. The metaphors it conjured were highly pertinent. Through this introspection I became interested in ideas like barriers, confinement, boundaries, horizons, chaos, liminal spaces and structure. The whole project was a personal and creative exploration of the place this hedge conjured up within me.

So how did you start work?

After observing, recording and drawing for some I firstly made a one-off drypoint etching. I started by doing a drawing on a big aluminium plate, which I scratched into with a drypoint needle. I was just doing it on the sofa in the front room, scratching away at it in the evenings. Then, when I went into the print workshop to print the plate, I couldn’t believe how angry it looked. My immediate reaction was, ‘I’m going to leave that. I’m not going to do anything with that at all.’ They were quite visceral, those first emotions, they were really powerful. A hedge is a barrier, and I had put up some emotional barriers for the best part of 35 years. So that first piece is about the anger and the spikiness of the hedge, and the complete and utter chaos in the hedge, but also that it seems very organised. Although confronting, I was really interested in and excited by the range of emotions coming straight out of me and into the artwork.

I’m interested in you creating your work at home, on the sofa, at the kitchen table. How does that affect your work?

I really wish I had a studio, but I don’t. The idea when we bought this house was to convert an outbuilding into a studio, but it got full up with racing bikes and skateboards and boys’ stuff. When the boys get their own homes, I’ll have some more space.

As a woman there is something interesting about not having a studio and being forced to create my work in a domestic environment. I think there are quite interesting politics around that. Not all women have studios or can afford to, and they are forced to use the kitchen table. It does make me go out and draw quite a lot as well, which I like. I also like the idea of a community of artists, because we are quite isolated here. I enjoy going into Leicester and seeing other artists and talking to them and having that interchange as well. That’s really important to me, having relationships with other artists, especially women artists. During the Hedge Project I wanted to meet with other women artists more often, so I set up a women artists’ support and networking group that would enable us to support each other around our work, to offer constructive support to each other. We started to meet last year.

How did the work develop? Did you continue making more etchings?

No. I do lots of work on different pieces at the same time and in different media. I usually try and keep 2 or 3 plates spinning. I do textile work as well, so I try and keep a textile piece on the go and embroidery. So that is something else that I can do at home in the evenings, if I’m not creating printing plates.

I applied for some mentoring from the Beacon Art Project in north Lincolnshire and successfully got onto that. For that you got two day long mentoring meetings. My mentor, John, came and had look at the work and said, ‘It’s all very good, but it all looks very much the same. You need to focus on something. What is it you’re thinking about at the moment? What’s the most recent piece of work?’. I told him I’d been doing this work on some hedges around here, and he encouraged me to look at a hedge. So that’s how I came to focus on one hedge and that was a hedge that I was looking at closely because of its geography, its placement. It’s in a really beautiful place on the horizon and it was easily accessible. I particularly liked the way that the light shone through it so you could see the structure and the pattern, the beautiful lines. Also the understory of plants that were growing through it, as well as the structure of the hedge itself. So the work is also about the ‘music’ that’s growing through it.

John then asked me where I wanted to go next with the work, and I said that I’d really like to get funding. I’ve spent all my life supporting other artists through museums and galleries and working with other artists, but I’ve never done it enough myself and at that point I needed to do something for myself. I started to go to galleries and places where I already had a relationship, where I knew the people that I could go to and say, ‘This is my story. Are you interested in this as a proposal, as a project with community engagement and artist-led days?’ Eventually I managed to get Nottingham University, Leicester Print Workshop and Kettering Museum and Art Gallery as my thread of spaces. I wanted the exhibition itself to be like a little hedge running through the Midlands.

I was delighted to get the exhibition space at Kettering, since it is the nearest to the actual hedge. They also have a relationship with the CE Academy, which is for students that have been excluded from school. So with each venue I worked with the educational outreach officer and looked at groups that they weren’t reaching, young people or adults with mental health issues. Because of my experience I wanted to give back somehow, because we all hit borders, barriers and edges in our lives, and we need support and perhaps creativity can be a way of understanding that.

I also spent a day at each venue gathering hedge stories. I asked people if they had a story about a hedge. First of all I think they wondered what I was on! Then, as I engaged them a bit more, people told me some fantastic stories. One guy told me about how trees were interspersed in hedges to stop witches from flying over them. I’d never heard that story before. Two other men I spoke to were railway workers, who told me that they used to grow fruit trees in the hedges along the railway lines, hiding them there, and they would harvest plums, apples, cherries. I thought that was such a lovely story, the idea of these men cultivating the railway network. I heard lots of these wonderful stories, and that was when the Woodland Trust got interested. They were excited by the fact that I’d got 36 accounts of people’s relationships with hedges and told me that it was a substantial record of narrative local history. So we’re talking at the moment about doing something with those stories and I’m hoping that will be the beginning of an ongoing relationship with the Woodland Trust.

Because of my personal politics I can’t just throw art on the wall and then walk away. I have to have a relationship with the people that are coming in to see it. I want to be able to say, ‘This is my thinking. I’m not some special person. I’m just a normal person like you. This is how I see the world. This is how I interpret what I see and experience. This is my way of looking at things.’ I really enjoy doing that. The sharing.

What sort of effect did the workshops have on the kids that you were working with?

They were amazing. They all came in with their shoulders hunched, not making eye contact, with a what-are-we-doing-here look on their faces. They wouldn’t do anything at all for the first half hour, but in the end they all produced amazing work. I brought a big bag of stuff from the hedge itself, clippings and twigs and leaves and weeds and things and showed them how to print directly from nature, and then to cut things up and do different things with them, playing with different processes and techniques. I was getting them to see how you can use nature creatively to communicate ideas about yourself and your experiences.

You use a range of different media. How did that exploration come about and what did each medium add to your experience of creating that body of work?

So it starts with a sense or a notion of something and then I do drawings and play around with shapes and forms, all because I want to get across a particular feeling about something.

Some pieces came about specifically because of the lichens in the hedge. I wanted to make some ink from them so I scraped some of it off and mixed it with some oil and Vaseline and rollered this lichen ‘ink’ onto a piece of paper. I felt that I needed to overlay some forms of the hedge onto that, so I scratched into these little plastic plates – this time with a scalpel, as I wanted really fine lines – and each colour is a different plate. I repeat and use the same plates in different pieces in different ways. Sometimes they will be very ordered, other times more chaotic.

I also made some lino plates and then overprinted them. I did it just as practice, wondering what those shapes that I’d drawn, classic hedge shapes, would look like. The hedge was cut at the top and some I turned upside down and arranged vertically. I was just playing around, but when I looked back at this one strip I’d done I thought they looked a bit like hieroglyphics. I was also thinking about the counselling I’d been through and the idea of tea and sympathy and so I stained the paper with tea, which is something you do to make paper look old. I was enjoying putting all these different things together and then people started saying how it looked like music or some sort of language. And I thought about the sort of language that my therapist used, which was really interesting to me. I liked the way that she used particular words. So I started to develop this hedge language. There was also something about the hedge standing up for itself. Because I am the hedge.

What was your emotional process with each of these different techniques. Did it bring up something different for you each time?

I don’t produce editions of things. They’re all one-offs. Once I’ve said what I want to with a piece, I’m not interested in repeating it. So I like the single process. I like the high failure rate inherent in this too, because sometimes valuable things come out of what you initially think is a mistake.

It was a visual, creative and emotional journey going through the seasons and each season threw up something different for me. I was very disciplined about thinking, ‘What is it you’re doing? Why is it you’re looking at that? Is it the structured branches or the things growing through them? Is it the fruits or the lichens or the soil?’. So I investigated all of it. I made rubbings, drawings, textiles, embroidery, dresses. I just wanted to do all of it and make lots of work exploring everything I was feeling. It’s an intuitive and organic process though. I don’t go in with a preconceived approach or necessarily an idea of which medium I will use.

Tell me about the dresses.

I wanted a bit of me in the hedge. I wanted to put a bit of me in there. So I made four dresses and one of them I left out in the hedge for a year, where it accrued all the dirt and detritus of the hedge throughout the seasons.

And then I worked with the lichen in the hedge, which became quite interesting to me because I discovered that they thrive in toxic environments as well as clean air. I contacted a local lichen expert and he came over and catalogued the lichens in the hedge for me, and he told me that lichens aren’t always a signifier of clean air, which is what I had always thought. Sometimes they grow because of particular toxins in the air, even petrol and diesel fumes. So the bright yellow lichens are reacting to toxins in the air, sulphur apparently.

So I did a big 12 foot long wall piece about lichen with this puff binder, which has a three dimensional quality like lichen, and I also made a dress using the same technique as well as flocking. That was the first time I had ever worked with screenprinting, which I’d always found it a bit flat previously.

I wanted to ask you about the mapping project too.

That’s an older piece of work also looking at issues around family relationships. Some of the same things as became apparent to me in the Hedge Project, but I wasn’t conscious of them then.

I had been invited to show some work in Leicester that was based at the depot which was an old bus station. We had to come up with work that was linked to the depot and the immediate area in some way. I remembered my dad cleaning the oil from the car dipstick with his handkerchief when I was a child, and I thought that bus drivers in the ‘30s and ‘40s must have had hankies in their pockets for just the same reason.

And I love hankies, anyway. I love proper fabric handkerchiefs. So I looked at some of the very oldest maps of Leicester at the library there and did some drawings of them and then printed them onto cotton handkerchiefs. To display them I made a gold paper lined box with a cellophane window, just like the ones my aunty would give me as a girl at Christmas.

I also hand-stitched secret messages onto them which, as on a map, were like a key. Things like ‘rough pasture’, ‘rocky ground’ and ‘motorway’, and used some of those phrases as metaphors to describe how I was feeling.

I also made a series of map works about being stuck at home; cloths and floor cloths, which I stitched landscapes onto. And I made some hankies that are about the forest behind our house, from aerial maps of the forest. Sometimes when I’m out walking I find people that are lost and a few times we’ve had people appear in the village who think they’re somewhere else, so I’ve had to give them a lift back to the car park on the other side of the forest. I felt like I wanted to be able to give these people something. Something that I could easily get out of my pocket, to be able to say, ‘Here you are. Here’s a map, so you won’t get lost again.’

What are you working on now?

I am currently doing an evaluation for the Arts Council and embarking on a body of new work based on natural lines, cracks and gaps in the landscape. We have Rockingham Forest behind our cottage, which is on the site of an old Second World War army airfield, RAF Spanhoe. So I’m in the woods currently, with an old map from the ’40s that my neighbour gave me, looking at the way nature is reclaiming the cracks and small spaces in the old concrete paths. The deteriorating concrete has broken up into really beautiful shapes, softened by moss and other vegetation. In the spring the cracks are full of tiny primrose seedlings. I love seeing nature saying, ‘It doesn’t matter what you lay on top of me, I’m still going to grow through it.’ I just really love that idea of nature taking over something ostensibly ugly, like concrete, and making it really beautiful.

Interview, artist and location photographs: Huw Morgan. All other photographs courtesy Claire Morris-Wright

Published 23 February 2019

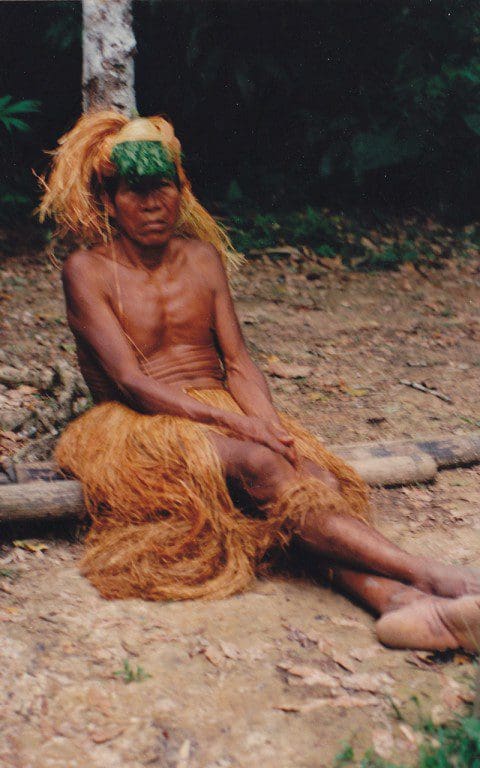

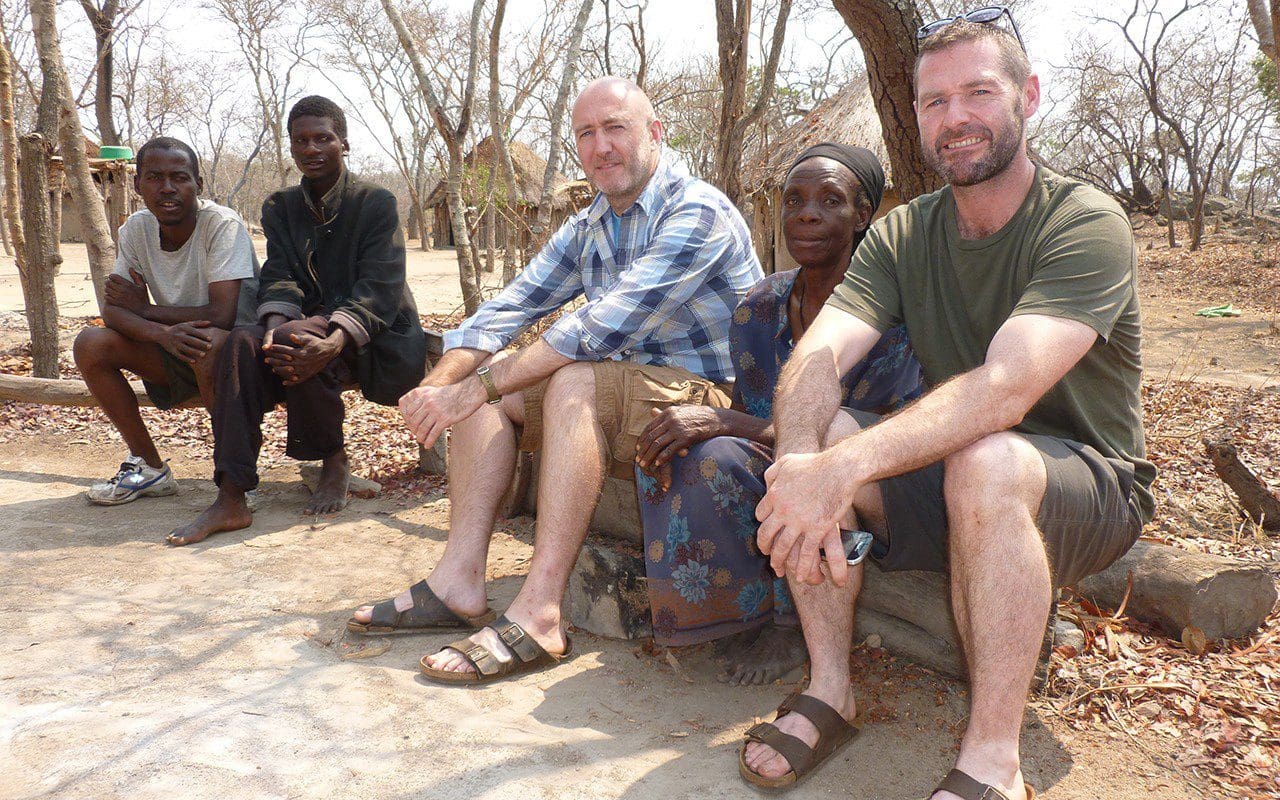

Simon Jackson (above right) is a pharmacognosist and cosmetician who is passionate about creating personal products that are derived from scientifically proven, sustainably produced active plant extracts. After a long and wide-ranging career as a scientist, researcher and cosmetic product innovator, for the past two years he and his husband, John Murray (above left), have been developing a new range, Modern Botany, using British native plants grown near their home in the West of Ireland. Simon, you have taken an interesting and varied route to where you are now. Can you give us a brief explanation of where your interest in the therapeutic uses of plants started and your training ? Interesting? Varied? I think they call it a career portfolio nowadays! OK, how long do we have? As you can imagine I’ve got a lot to say on plants and their therapeutic uses. I guess it all started in Lincolnshire. I grew up in a small village and my love of plants came from my grandmother, Cath Jackson. She was a keen amateur gardener and she taught me all the Latin names of plants when I was very young. She had a small plot of land and was very proud of all her plants and I used to help her gardening. She had a beautiful allium that came up year after year, and it was quite unusual in the early ‘70’s to have such unusual plants. She introduced me to Sir Joseph Banks, a famous Lincolnshire botanist. There is a big monument to him in Lincoln Cathedral, and his home town of Horncastle was close by, so the seed was planted. Skip forward about 20 years, and I found myself studying at Manchester Metropolitan University in 1989. I did a course in Applied Biological Sciences and specialised in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. Back in the late ‘80’s it was called Plant Defence Mechanisms. When plants are put under pressure externally or attacked by herbivores, they excrete defence chemicals. Salicylic acid is one of them. It has a bitter taste so wards off any herbivores, but it also has medicinal properties for humans too. Aspirin we call it. It was here that I learnt about ethnobotany, and how traditional cultures use plants. For example, it was the native Americans who used willow bark during childbirth as an analgesic to help with pain relief. I just thought this was amazing and so, as part of my degree, I undertook an expedition to Indonesia. The year was 1992, and it was in the middle of all the atrocities in Timor, but I was quite gung-ho even back then, and just wanted to learn more about plants and their traditional uses. We lived on an island called Sumba. It was very primitive back then, no luxury hotels or surf dudes like there are now, but I took part in what was one of the first pharmacy conservation projects in an Indonesian primary rainforest. I was cataloguing species of plants around the island and understanding from the locals any economic uses they had, which could be medicinal, or as dyes or fuel or even as building materials. The aim was to set up some sustainable practices for harvesting these plants. It was on the island of Sumba that I remember being introduced to a village chief. I had wandered off into the rainforest one day a bit too far on my own away from base camp, and he found me walking in the wrong direction (I have a terrible sense of direction) and brought me back to camp on the back of his Sumbanese pony, an indigenous breed of horse on the island. Seeing the hornbills flying back at dusk and the Sumbanese green pigeons (they look like parrots) it was here that I learnt from him about the traditional uses of plants, and it was here that I had my cathartic moment and realised it was traditional plants I wanted to study. That’s why I had majored in Drug Discovery and Toxicology. I also worked in the Herbarium in Bogor, and met Professor Kostermans, an amazing ethno-botanist, who regaled me with all his stories of expeditions in Indonesia, Borneo and Sumatra. He was a POW during the war and only survived by learning from the locals how to utilise the native plants for food and medicine. And that was it. I was hooked. Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

Simon (left) on a field trip to Indonesia in 1992

I decided that, to be taken seriously, I would need to further my education and get a Masters and PhD in Natural Product Science. I did a bit of digging and found one of the only centres to do such a thing was King’s College in London, where they had a Pharmacognosy Department in the School of Pharmacy. I enrolled in a 3 year PhD programme in 1993 under Professor Peter Houghton. It meant that I had to get top class honours in my first degree, but it was something I really wanted to do and so passed with flying colours.

It was a bit of a culture shock initially, going from ‘Madchester’ in the early ‘90’s to Chelsea in London, but it was under Professor Houghton that I really learnt my trade. Pharmacognosy has been around for a long time and we can record how humans have used plants back to the Stone Age, but Western medicine goes back as far as the Greek philosophers. Dioscorides (40-90AD) was one of the first to document the ‘De Materia Medica’ or medical material, and it’s from here that we find the origins of Western medicine. The ‘De Materia Medica’ was the first precursor to all modern pharmacopeias. Meaning ‘drug making’ in Greek these are books published by governments or medical bodies which contain the directions for the identification of all compound medicines.

So at King’s College, I learnt that pharmacognosy is a multidisciplinary study drawing on a broad spectrum of biological and socio-scientific subjects, but in short: botany, medical ethnobotany, medical anthropology, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice.

The contemporary study of pharmacognosy is broken down into;

Medical ethnobotany: the study of the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes

Ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances

Phytotherapy: the medicinal use of plant extracts

Phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants, including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources

Although most pharmacognostic studies focus on plants and medicines derived from plants, other types of organisms are also regarded as pharmacognostically interesting, in particular microbes, like bacteria, fungi etc – think antibiotics – and more recently marine organisms, for example some interesting anti-cancer products derived from sea sponges.

If anyone is interested I can talk about this for hours, but what I’m finding is that there are less and less places to study this arm of medicine. It’s usually linked with pharmacy departments, but what’s interesting is that more and more people are asking me where they can study this.

Anyway, there finishes my first lecture in pharmacognosy! I have several more weeks worth of lectures, but I’ll leave it there for now. I hope it gives you a good overview.

So, after King’s College, I then did a Post Doctorate at Kew Gardens in the Jodrell Laboratory. It was 1993 when I started at King’s, so it must have been around 1996. I remember living in digs in Chelsea – a lovely old farmhouse in Parsons Green – and Carol Klein was living there in the lead up to the week of the Chelsea Flower Show. So I ended up helping her out putting her stand together in the marquee (I was the manual labour), but that was when I first met you, Huw, and Dan. Carol introduced me to you both and I think Dan had just won his first ever Gold at Chelsea. Anyway, I digress.

You have travelled a lot to research the plants that you have been interested in, and spent periods of time living with indigenous tribes in Africa and South America. What were some of the most interesting things you discovered on your travels ?

Yes, I have been lucky to travel to many places around the world. As I said I started out in Indonesia, which really inspired me to study medicinal plants. I remember meeting the local ladies in the market and they were making Jamu, a natural health tonic, and selling all the raw ingredients. Every tribe or family had a different recipe. It was amazing to see everyone so healthy and living to ripe old ages with no NHS interventions, chewing betel nuts and spitting the bright red saliva all over the floor.

Next was South America. I was lucky enough to be invited as guest speaker at the first Pharmacy from the Rainforest Conference in the Amazon in the ACEER Camp in Peru. It took a few days by dugout canoe to get to the research station, but what an amazing experience. It was here that I met the famous American ethnobotanist, James Duke, and Mark Blumenthal and the rest of the American Botanic Council team. I now and again write articles for their Herbalgram magazine on medicinal plants.

In the rainforest of the Amazon (this is pre-Sting going there), I had no idea what to expect, but we witnessed the shamanic ayahuasca ceremony and learnt how to harvest the raw ingredients to make the hallucinogenic recipe. I met my first shaman, which was quite an experience, and learnt so much about South American plant species. One that sticks out is the Croton lechleri or Sangre de Drago. I still use it today if I get bitten or if I get a small cut. It’s great as a ‘second skin’ and really does reduce any inflammation from bites. Do check it out. You can buy it online and in good health food shops.

The ACEER Camp in Peru

The ACEER Camp in Peru

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.

My theory is that plants used for traditional medicine make greater leads for new drug discovery as they have been used for many thousands of years, so there must be a reason why they are being used for medicine. Statistically drug development is more pronounced when there has been some sort of traditional use of the plant. Some people make reference to the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’, an old medieval term which means that the plant looks like the disease or the part of the body that it should treat. For example, ginseng root looks like a little body with a head and legs and arms, so it is used as a tonic or a treatment for the whole body. Some say the sausage tree has grey, scaly skin, so it might have used to treat skin diseases. In Africa, it has been used traditionally to help with dark skin spots (solar keratosis), especially around the face. These can lead to skin cancer, so in theory the plant might be a treatment for skin cancer.

I spent my PhD trying to identify if any of the plant was bioactive. For example, the fruit or the roots or the bark or leaves of the tree. What I actually found was the fruit was bioactive against melanoma cells in vitro (in the test tube). We did a bioassay guided fractionation, and identified the actual compounds that were responsible for the activity. However, with today’s modern medicine it’s not always the magic bullet or the single compound that is the active constituent. It might be several compounds working together in synergy that are causing the desired effect. As mentioned, I think there are a lot more studies that need to be undertaken, especially with the positive results we found at King’s College, but clinical trials can take many years, and are very costly. It’s quite a conversational starter though when I arrive at Customs with several Kigelia fruit in my backpack.

Jaguar shaman in the Amazonian rainforest

What can you tell us about your research into the uses of African medicinal plants as therapeutic agents in oncology ?

I did a lot of research as part of my PhD. My professor was one of the world experts on Kigelia pinnata, the sausage tree, which has been used traditionally against malignant melanoma and solar keratosis, and my PhD thesis was a study of compounds isolated from this plant against skin cancer. I worked at Charing Cross Hospital in London, isolating the active compounds and testing on human melanoma cell lines (tissue culture). We identified several compounds that showed activity, but it can take over 10 years and up to $100M to discover a new drug, so this work is still ongoing and will take many years to create any new medicines.

You yourself are now a world expert on Kigelia pinnata. What can you tell us about it ?

Crikey, that sounds grand, but I guess there are not many people who have researched Kigelia pinnata. I co-wrote a lovely paper for Herbalgram which gives you an outline of the plant. It’s quite an amazing species which belongs to the Bignoniaceae family, which also includes the catalpa tree from South America. It contains a compound called lapachol, which was taken forward for cancer research, but it was found to be quite toxic in vivo (animal)studies and so was dropped, but I still think it’s a plant family that needs a lot more research to be undertaken. I’m hoping one day I can pick up the baton again and take this research further.