ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY REGISTERED OR A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY REGISTERED OR A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

ALREADY A PAID SUBSCRIBER? SIGN IN

The great cut back this year happened over three weekends, starting at the end of February as soon as I saw new life, and finishing with time to assess the garden before mulching. It is a very good feeling when you finally decide to let go of what came before and embrace the change. A time you have been waiting and planning for and one that, this year, feels particularly good to embrace with the uncertainties that lie ahead of us.

The growth feels early now after the mild winter and, by the time we cleared the last bed, many of the perennials had already pushed into last year’s growth. Some, like the baptisia were a dream to pull away. New shoots in a perfect arrangement of expectation, the colour of red cabbage, the old stems toppled and splayed and waiting to be lifted. The sense of urgency was expressed in the delicate lime green of fresh hemerocallis foliage, which I wished I’d cleared around earlier but, standing back at the end of the day and with the volume of last year gone, it was good to see the established rosettes, each with their own character and story to tell so clearly mapping their territories. The new ruby foliage of peonies marching along the path, and the bright buzz cut of the deschampsia already re-growing from their shearing. Yet to emerge, the late season panicum are making it very clear that they are lying in wait and it is only at this time of year that you are able to make these observations. Put them on the wrong side of an early to rise sanguisorba and they will be thrown into shadow and not make it off the starting blocks.

The window between cut back and mulching is a good time to look and I like to take a day or maybe two combing the garden to see where actions might be needed. The long-lived clump formers like the peonies and baptisia will go years before they need any attention. All I have to do there is give them their domain and restrict an unruly, faster-growing neighbour. Stooped and looking close to retrace the ground-map of rosettes, I make mental notes of what needs doing now and what can wait for another year. When all is laid bare is when you see the life cycles, when the runners give away their secret behaviours and the clumpers either make you feel at ease, because they do not yet need division and have life in them yet.

Those that will dwindle in the coming year and need re-vitalising exhibit this with a monkish bald patch in the middle of the plant where the new growth is moving towards fresh ground. I have deliberately steered away from perennials that live on a short cycle and have taken time, for instance, to choose asters that are clump-forming and need division less regularly than those that run or burn out fast if they don’t. But there are favourites that do take a little more time. When I put aside a whole morning to carefully retrace the runners from the Pennisetum macrourum I think about the Hemerocallis altissima that won’t need my attention. With plants you haven’t grown before or don’t know as well, you need to build in this time to become familiar with their habits and weigh up whether something is going to become an problem. The pennisetum comes close to being problematic but, when it captures the wind in its limbs in midsummer, the balance is fairly tipped.

Singling out the bald patches has not taken much time for there are just a few plants that are showing their age in this young garden. As it ages I expect there will be more and I will need to pace myself and anticipate action before it is needed, singling out a few plants each year that look like they need refreshing and doing so before the season is upon me. This year the perennial Angelica anomala and the hearty Cirsium canum have both required splitting. They have been fast to make an impression in the new garden, but are doing so at the expense of reliable longevity. I do not begrudge this quick turn-around, for their presence in the planting is strong and certain. In its early awakening I can see that the dark limbed angelica has moved away from the original crown with small offsets offering me plenty of material to pot up and grow on for the autumn. The most robust sections, with good roots, storage rhizomes and potential have been replaced in the same position with the ground regenerated gently by forking in compost.

The cirsium were divided into three, the best part replanted in improved ground and the remainder discarded. This is hard to do, but it is a gentle giant and there is only room for a small number. Standing seven feet tall, glossy and without prickles but looking like it should, it is a plant with attitude which, like the pennisetum and the angelica, make up for needing a little more attention than the crowd.

Words: Dan Pearson | Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 14 March 2020

We leave the garden now to stand into the winter and to enjoy the natural process of it falling away. The frost has already been amongst it, blackening the dahlias and pumping up the colour in the last of the autumn foliage. Walk the paths early in the morning and the birds are in there too, feasting on the seeds that have readied themselves and are now dropping fast. I have combed the garden several times since the summer to keep in step with the ripening process, being sure not to miss anything that I might want to propagate for the future. The silvery awns on the Stipa barbata, which detach themselves in the course of a week, can easily be lost on a blustery day. This steppe-land grass is notoriously difficult to germinate and a yearly sowing of a couple of dozen seed might see just two or three come through. My original seed was given to me in the 1990’s by Karl Förster’s daughter from his residence in Potsdam, so the insurance of an up-and-coming generation keeps me comfortable in the knowledge that I am keeping that provenance continuing. The seed harvest is something I have always practiced and, as a means of propogation, it is immensely rewarding. Many of the plants I am most attached to come from seed I have travelled home with, easily gathered and transported in my pocket or a home-made envelope. Seedlings nurtured and waited for are always more precious than ready-made plants bought from a nursery but I have learned the art of economy and sow only what I know I will need or think I might require if a plant proves to be unreliably perennial for me. The Agastache nepetoides, for instance, came to me via Piet Oudolf where they grow taller than me in his sandy garden at Hummelo. However, they are unreliable on our heavy soil and need to be re-sown every year. Fortunately, they flower in the same year and I can plug the gaps where they have failed in winter wet with young seedlings sown in March in the frame and planted out at the end of May.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Agastache nepetoides

Over the years, as much by trial and error as by reading about the requirements and idiosyncrasies particular to each plant, I have learned the rules. The Agastache for instance will not germinate if the seed is covered, so they will fail to appear spontaneously in the garden if you mulch or sow and then cover the seed, as I usually do, with a topping of horticultural grit. The seed needs light and should just be gently pressed into the surface so that they can be triggered. The Agastache seed keeps well and is easily sown in spring, but the viability of seed is different from plant to plant. Primula vulgaris gathered and sown directly a couple of years ago saw seedlings germinate readily within a month that same summer. Last year I was busy and waited until September to sow, but the seed had already begun to go into dormancy, an inbuilt mechanism to save it in a dry summer. The overwintering process of stratification, which will unlock dormancy with the freeze, thaw, freeze, saw the seedlings germinate the following spring. The plants consequently took a whole six months longer to get them to the point that I could plant them out into the hedgerows, but I learned and will save myself that delay come the future.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Molopospermum peleponnesiacum

As a rule the umbellifers tend to have a short life and the seed does not keep, so I sow my giant fennel, Astrantia and Bupleurum as soon as the seed is ripe and overwinter it in the cold frame. This year, for the first time. I have sown Molopospermum peleponnesiacum and, though it is a reliable perennial, I am keen to see if I can rear some youngsters. This ferny-leaved umbel is early to rise and I love it for the gloss and laciness of its foliage and the horizontality of its lime green flowers. I have it amongst my Molly-the-Witch peonies and their early presence together is a good one. I’m also simply curious to learn more about the life cycle of this European umbel, as I find I understand a plant better if I know how long it will take to become a parent and what it takes to get it to the point of seeding and germinating successfully.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Paeonia delavayi

My Paeonia delavayi are the grandchildren of an original plant I grew from seed I collected when I was nineteen and working at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The plants in the garden have started to lose whole limbs this year, which I am putting down to the heat, but it could just as easily be honey fungus. Having a few youngsters in the background is good insurance, but I am sowing the seed fresh because peony seed needs a chill and sometimes two winters before growth appears above ground. The first year is all about the formation of roots so, as a general rule, I never throw a pot of seed out for two years just in case.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

Asclepias tuberosa

This is the first year I have grown the tangerine milkweed, Asclepias tuberosa, and would like to get to know it better. It is said to suffer from winter wet, which is a given living where we do in the West Country, so my seed sowing is insurance again and a means of bulking up the little group I have amongst my black-leaved clover. The seed is exquisite, the claw-like pods rupturing on a dry day to spill their silky contents on the breeze. Reading up reveals that the seed also needs winter stratification, so I have sown it now in a lean, gritty compost to ensure it is free-draining and that the seed doesn’t sit wet. A gritty seed compost will ensure the seedlings search for nutrients and grow a good strong root system once they have germinated in the spring. I prefer to top dress with grit rather than soil to inhibit moss and algae build-up, which can cap the pots if they are sitting around for a while in the frame.

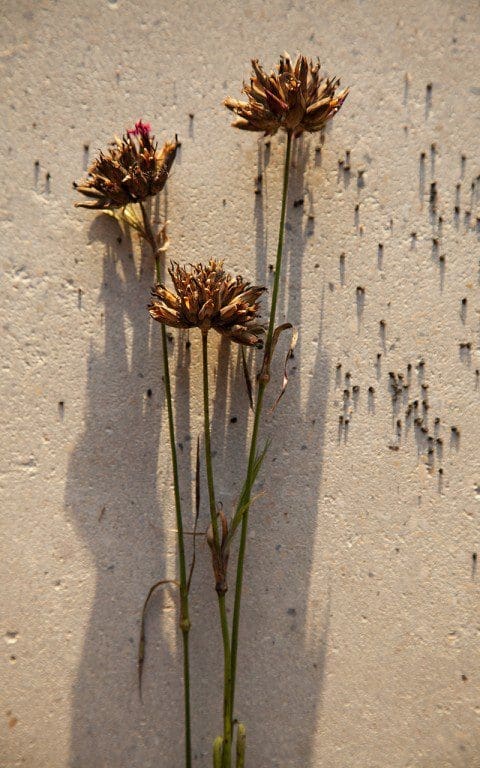

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018

Dianthus carthusianorum (in second image with Achillea ‘Moonshine’)

Although I like to sow most of my hardy plants in the autumn to avoid storing them when they could be beginning their journey, I like a few in hand to simply scatter about and help in the process of naturalising where I want my plants to mingle. The Dianthus carthusianorum are this year’s project, and so I am scattering seed at the tops of my dry banks where I hope they will take in the most open parts of my wildflower slopes by the house. A cast of thousands is easily made up in a handful, but it takes only one to begin a colony.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 17 November 2018 The winter form of last season’s skeletons has been easily as interesting as the first summer in the new garden. Though their muted presence is not the thing you plan for first, it is an aspect that is worth considering for the ghosts that are left behind. Some, the daylilies for instance, leave nothing more than the space they took in their fleshy growth period, but those that endure are arguably as good as they were in life. Without the distraction of a growing season, its pull of colour and the steer of upkeep, you are free to look at the dead, left-behind forms anew. Blacks and browns, sepia, cinnamon and parchment whites are far from monochrome and their structures and seedheads are worth planning for in combination.

Snow flurries and rain laden winds began the topple in January, but the garden endured and weekly we have observed it falling away, shifting, dropping back and thinning. The vernonia, with their biscuit seedheads, stood tall amongst the pale spent verticals of panicum and I welcomed the repeat of the finely tapered Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ together with the bottle-brushes of Agastache ‘Blackadder’. The birds loved them too and some days the garden has been alive with activity with the foraging for seed and overwintering insects looking for shelter. The black stems of the veronicastrum were good amongst the molinia stems, but their seeds were stripped by mice early on. The grasses have been key for their foil, their pale colouring bright on dry days, warm in the wet, and their plumage acting as light catchers when the sun has broken through.

The clearance required to make way for the new season has been carefully judged. There comes a point, some time when the bulbs are showing you that new life is on its way, that the skeletons begin to feel tired. We have also had to pace ourselves, for it has taken five man days to work through the areas that were planted almost a year ago and, this time next year, it will take another three when the areas of the garden that were planted last autumn are grown up.

The lower bed before being cut back

The lower bed before being cut back

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

From left to right skeletons of Sanguisorba ‘Blackthorn’, Verbena macdougalii ‘Lavender Spires’ and Vernonia arkansana ‘Mammuth’

We made a start in early February, working from the high ground that drained most freely and sweeping round to the heavier low bed by the field in a second session a fortnight later. In just two weeks buds that had been thoroughly dormant were already showing at the base of the euphorbias and the first new shoots on the grasses signalled the shift and the need to move things forward.

Before we started, I waded into the beds and marked the plants that I knew I wanted to change, for there are always adjustments that need to be made in a new planting. The densely-flowered Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ will be exchanged for the more finely tapered L. virgatum ‘Dropmore Purple’, while the Artemisia lactiflora ‘Elfenbein’ that read too strongly as a group once their pale flowers caught the eye were left standing so that I could find them again easily and redistribute them so that their presence is lighter this summer. The changes will be different every year, but it is good to have time in hand to make them whilst the plants are more or less dormant.

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

After clearance bamboo canes mark the remains of Lythrum salicaria ‘Swirl’ in the top bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

Ray and Jacky work their way through the lower bed

The feeling of working through and stripping away is always a mixed one. I would leave some plants standing for longer, indeed, I have with the liquorice and the fennel, but the spring clean is good. Underneath the tussocks of deschampsia we unearthed the nesting places of voles, which had already tunnelled out and made a winter feast of my inulas on the banks. We only found one, which scurried to safety and I was relieved to find that their damage hadn’t been greater. Last year when lifting the molinias from the stockbeds to split them in readiness for the new planting, I found them almost completely hollowed out, roots and crown all but gone under the protective thatch of winter cover. There are pros and cons to leaving the garden standing and, although I prefer to do so, it is a good feeling to see the clean sweep reveal the planting again in new nakedness. Tight clumps, indicating quite clearly now that they have broadened, how the combinations were set out on the spring solstice almost a year ago.

The dry, cut material was piled high on the compost heap where it will be topped by some of last year’s compost to help in rotting it back for the future. And at the end of the day, as light was dimming, we carefully raked between the plants so as not to disturb last year’s mulch. A couple of weeks later I combed through the beds again to winkle out any seedlings that we’d missed in the first pass. Dandelions already in evidence and ready to take hold in the crowns of the grasses and buttercups and nettles that been secretly travelling in shade under the cover of summer growth. The beds that were planted and mulched last year will only be topped up this year where they have been disturbed where I’ve made alterations. Hopefully growth will be sufficient to suppress all but the strongest of the interlopers. Although we are still waiting for the planting that went in during the autumn to show itself enough before mulching these new areas, it won’t be long now until the need to move will be upon us and the garden once again dictates the pace.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 24 February 2018

The hush and the breathing space that comes, now that the leaves are down and the grass has finally slowed, is palpable. In the mild spells between freezes I take this opportunity to square up the holding area by the barns. This is where one day I plan for a greenhouse, but for now it is where I propagate and look after the plants that are waiting for a home. The cold frames which reared the spring seedlings are now packed to the gunnels with plants that need protection from the lethal combination of winter wet and freeze. Auriculas and the Mediterranean herbs are kept on the dry side and the autumn seedlings and cuttings will make a surprising leap forward with this little extra shelter. Out in the open and hunkered together for protection are bulbs to go out in the spring, once I can see exactly where they need to be and that they are the correct varieties, as well as youngsters that are ready and waiting for areas that are not quite prepared in which to set them loose. This backlog is a perpetual conundrum, but I have a three-year rule so that the holding ground avoids becoming a corner of shame. If they cannot be found a place, they will be put out on the lane with a sign saying, “Please help yourself”. Very few are left unclaimed and I trust they find good and unplanned for new homes. One of the cold frames

One of the cold frames

Auriculas

Auriculas

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Narcissus

It is always good to start the year by planting trees and I am happy to use this window in the season to liberate the chosen few so that by the end of the holidays I am organised and ready for a new year. If they have been potted on annually, the woody seedlings are just about perfect at the end of a three-year period. This year, the first to be liberated will be the small-fruited form of Malus hupehensis, which were grown from the fruit of the single plant I have up in the blossom wood and are ready now to make the leap into open ground.

The seedlings are part of the learning curve that is illustrated in the trees they are going to join and in part replace. Destined for our highest ridge above the house, I plan for a huddle of berrying trees that will burst a cloud of blossom against the skyline in the spring. Three plants will join the hawthorn that were frayed out into the field from the Blossom Wood and the fourth will replace an ailing Malus transitoria. I have staggered this small, amber-fruited crab up the slope to meet the Blossom Wood on the high ground, but I have obviously pushed this Chinese species to the limit, for the higher up the slope they go the weaker they become, despite the fact that it is reputed to be resistant to drought and cold. With barely a finger’s worth of growth in the five summers they have been there, compared to several feet on those lower down the slope, they have demonstrated exactly what they require in the time they have been there.

I have dutifully mulched and watered and fed, but five years is quite long enough to know if a plant doesn’t like you, and so I feel justified in making the change. As I mature as a gardener, the question of time becomes more acute. I want to spend it wisely and use my energy well which, when you are investing years in trees, is important. That said, I am happy to plant young and though the saplings are barely up to my knee, they have the vigour of youth and will jump away with the below-ground growing time of winter ahead of them. The Malus hupehensis further up the slope has shown me that it has the stamina its cousin doesn’t and it is a good maxim that if you fail with one species, try another before giving up entirely.

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018

Planting a seedling Malus hupehensis

When planting woody material, and trees in particular, I prefer not to include organic matter to avoid an enriched planting hole from which the young tree prefers not to venture. Instead, the top sod, where the best soil lies, is upturned into the bottom of the hole where, by spring, it will have rotted down to provide the young roots with a good layer of loam. The roots of the young trees are given a sprinkling of mycchorhizal fungi to help in their establishment and from here they can make an easy way out into the surrounding ground. If I am to add compost, it will be as a mulch to keep the moisture in and the weeds down, and, in time, the worms will pull it to ground. Three years of clear ground around the base of a new tree is usually enough to give it the chance to get the upper hand and for the competition not to stunt growth. Growth which, in the case of my young Malus, and now that they have been liberated from the holding ground, will have nothing to hold it back come spring.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 6 January 2018 The self-sown sunflowers from the previous incarnation of the garden were the reminder that, just a year ago, we were growing the last of the vegetables here. I had allowed them the territory in the knowledge that this would be the end of their era, for they were in the bed that I now need back to complete the planting of the garden.

Felling them before they were finished was a relief, for suddenly, once they were gone, there was breathing space and the room to imagine the new planting. I’d also left the aster trial bed until the very last minute, eking out the weeks and then the days of its final fling. On the bright October day before we were due to lift, the bed was alive with honeybees, making the final selection of those that were to be kept for the garden that much more difficult. It was time to liberate the last of the stock beds, though, and to prepare the ground they occupied for a new planting.

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

The central bed cleared of sunflowers and ready for planting. The edge planting went in in April

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Newly planted divisions of Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ in the cleared central bed

Planning what to keep and what to part with is difficult until the moment you make the first move. Over the last three years we have been keeping a close eye on the asters that will make it into the new planting. Keeping the best is the only option, for we do not have the space elsewhere and the overall composition is dependent upon every choice being right for the mood and the feeling that we are trying to create here. So gone are the Symphyotrichum ‘Little Carlow’ which, although a brilliant performer, needing no staking and being reliable and clump-forming, are altogether too dominant in volume and colour. Aster novae-angliae ‘Violetta’ is gone too. Despite my loving the richness of its colour, having got to know it in the trial bed I find it rather stiff and heavy and I want the asters here to dance and mingle and not weight the planting down.

The Aster turbinellus, for instance, has been retained for the space and the air between the flowers, as has Symphyotrichum ericoides ‘Pink Cloud’ for its sprays of tiny, shell-pink flowers. I have also kept the late-flowering Aster trifoliatus subsp. ageratoides ‘Ezo Murasaki’ for its modest habit and almost iridescent violet stars held on dark, wiry stems. I have always known that Aster umbellatus would feature in the planting, and so I lifted and split my three year old trial plant last autumn and divided it into six to bulk up this summer. There were many more that didn’t make the grade though, and I was torn about losing them, my self-discipline wavering at times. However, Jacky and Ian who help us in the garden eased my conscience by taking a number of the rejects home with them, and the space left behind, now that they are gone and I have finally committed, is ultimately more inspiring.

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Asters to be kept were marked with canes

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

Ian and Sam digging over the upper bed after removal of the asters. The Aster umbellatus divisions and Sanguisorba ‘Blackfield’ stock plants in the middle of the bed await replanting

The reject asters

The reject asters

This is the second phase of rationalising the stock beds. In the spring, and to enable the preparation of the central bed, I split and divided the plants that I knew I would need more of come autumn, and lined these out in the top bed to bulk up; the lofty Hemerocallis altissima, brought with me from Peckham and prized for its delicate, night-scented flowers, the refined Hemerocallis citrina x ochroleuca, and the true form of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’, originally divisions from plants in the Barn Garden at Home Farm which I planted in 1992.

I have not found a red day-lily I like more for its rustiness and elegance, and some of the ‘Stafford’ I have been supplied with more recently have notably less refined flowers and a brasher tone. I have planned for it to go amongst molinias so that the flowers are suspended amongst the grasses. Hemerocallis are easily divided and in the spring the stock plants were big enough to split into ten or so; the numbers I needed for their long-awaited integration into the planting. In readiness for setting out, and with the asters gone, we have now reduced the foliage of the daylilies by half, lifted them and then left them heeled in for ease of lifting and replanting.

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

Hemerocallis, crocosmia and kniphofia stock plants cut back, heeled in and ready for replanting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

A division of Hemerocallis ‘Stafford’ laid out for planting

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

Jacky and Ray clearing and preparing the end of the upper bed

The kniphofia and iris I had decided to keep went through the same process in March, and so the Kniphofia ‘Minister Verschuur’ and Iris magnifica were moved directly into their new positions where, just a week before, the sunflowers had towered. Similarly, the Gladiolus papilio ‘Ruby’ and Crocosmia ‘Hellfire’, which have both increased impressively, were lifted and moved into their new and final positions. This was in order to clear the old stock beds to make way for the autumn splits and keep the canvas as empty as possible so that I can see the space without unnecessary clutter when setting out.

The remaining trial rows – some Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield that I want in number and two white sanguisorba that will provide height and sparkle in the centre of the garden – were cut back to knee height, lifted and then split in text-book fashion with two border forks back to back to prise the clumps apart. Where the plants were not big enough I was careful not to be too greedy with my splits, dividing them into thirds or quarters at most.

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

Dan splitting a stock plant of sanguisorba with two border forks

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

A sanguisorba division ready for heeling in

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

The grasses to be reused from the trial bed will be divided and planted out next spring

Although October is the perfect month for planting, with warmth still in the ground to help in establishing new roots before winter, I have had to work around the trial bed of grasses and they now stand alone in the newly empty bed. Although I will be planting out pot-grown grasses next week, autumn is not a good time to lift and divide grasses as their roots tend to sit and not regenerate as they do with a spring split.

The plants I put in around the Milking Barn this time last year are already twice the size of the same plants I had to wait to put in where the ground wasn’t ready until the spring. I hope that the same will be true of this next round of planting, which will sweep the garden up to the east of the house and complete this long-awaited chapter.

Words: Dan Pearson / Photographs: Huw Morgan

Published 21 October 2017

We are sorry but the page you are looking for does not exist. You could return to the homepage